Intersections between TikTok and TV: Channels and Programmes Thinking Outside the Box

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. TV Strategies, Social Media, and New Audiences

1.2. Media Adaptation to Social Media (Logic)

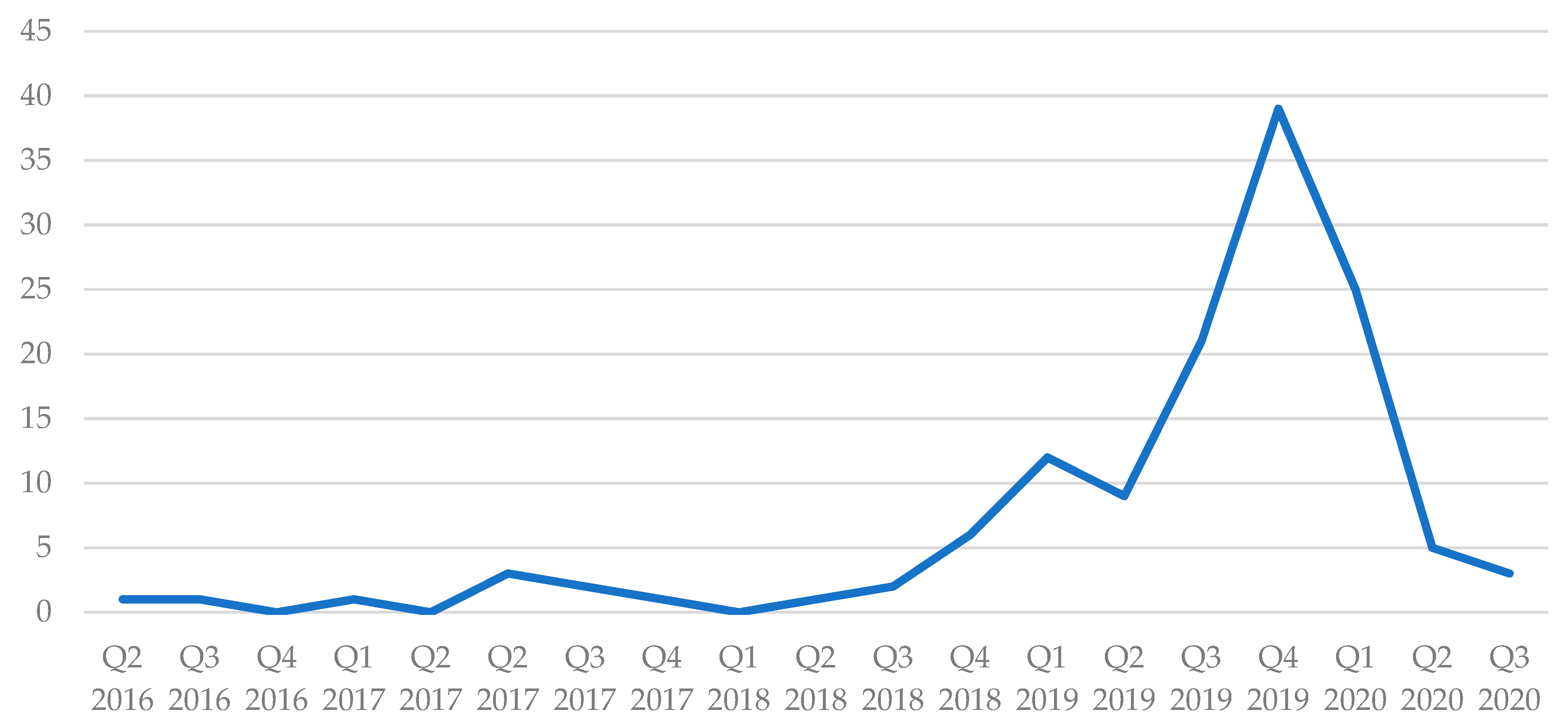

1.3. TikTok

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Exploring TV on TikTok

3.2. TV Strategies on TikTok

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abi-Habib, Maria. 2020. India Bans Nearly 60 Chinese Apps, Including TikTok and WeChat. The New York Times. June 29. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/29/world/asia/tik-tok-banned-india-china.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Ballesteros Herencia, Carlos A. 2020. La Propagación Digital Del Coronavirus: Midiendo El Engagement Del Entretenimiento En La Red Social Emergente TikTok. Revista Española de Comunicación en Salud 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, Sam, Paulo Victor Ribeiro, and Tatiana Dias. 2020. Invisible Censorship. TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by ‘Ugly’ People and the Poor to Attract New Users. The Intercept. March 16. Available online: https://theintercept.com/2020/03/16/tiktok-app-moderators-users-discrimination/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Boczkowski, Pablo J., Eugenia Mitchelstein, and Mora Matassi. 2018. ‘News Comes across When I’m in a Moment of Leisure’: Understanding the Practices of Incidental News Consumption on Social Media. New Media & Society 20: 3523–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, Michael A. 2017. From Editors to Algorithms. Digital Journalism 5: 753–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Gillian. 2010. From Television to Multi-Platform. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 16: 431–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekström, Mats, and Oscar Westlund. 2019. The Dislocation of News Journalism: A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Epistemologies of Digital Journalism. Media and Communication 7: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, Elizabeth. 2014. Tweeting on the BBC. In Making Media Work: Cultures of Management in the Entertainment Industries. Edited by Derek Johnson, Derek Kompare and Avi Santo. New York: NYU Press, pp. 235–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Elizabeth. 2015. Layering Engagement: The Temporal Dynamics of Transmedia Television. Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies 7: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Yu-Liang, Chun-Chin Chen, and Shu-Ming Wu. 2019. Evaluation of Charm Factors of Short Video User Experience Using FAHP—A Case Study of Tik Tok APP. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 688: 055068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Avilés, Jose Alberto. 2020. Reinventing Television News: Innovative Formats in a Social Media Environment. In Journalistic Metamorphosis. Edited by Jorge Vázquez-Herrero, Sabela Direito-Rebollal, Alba Silva-Rodríguez and Xosé López-García. Cham: Springer, pp. 143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Avilés, Jose Alberto, and Félix Arias Robles. 2016. Journalism Genres in Twitter’s Visual Formats: A Proposal for Classification. Textual & Visual Media 9: 101–32. [Google Scholar]

- González, Florencia. 2020. ¿Qué Están Haciendo Los Medios Latinoamericanos En TikToK? WAN-IFRA. February 27. Available online: https://blog.wan-ifra.org/2020/02/27/que-estan-haciendo-los-medios-latinoamericanos-en-tiktok (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Guo, Miao, and Sylvia M. Chan-Olmsted. 2015. Predictors of Social Television Viewing: How Perceived Program, Media, and Audience Characteristics Affect Social Engagement with Television Programming. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59: 240–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimson, Oliver L., and John C. Tang. 2017. What Makes Live Events Engaging on Facebook Live, Periscope, and Snapchat. Paper Presented at 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’17, Denver, CO, USA, May 6–11; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, Alfred, and Claudia Mellado. 2020. Dimensions of Social Media Logics: Mapping Forms of Journalistic Norms and Practices on Twitter and Instagram. Digital Journalism 8: 864–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hern, Alex. 2019. Revealed: How TikTok Censors Videos That Do Not Please Beijing. The Guardian. September 25. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/sep/25/revealed-how-tiktok-censors-videos-that-do-not-please-beijing (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Hill, Steve, and Paul Bradshaw. 2018. Mobile-First Journalism: Producing News for Social and Interactive Media. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2018. Understanding News Sharing Across Social Media. Journalism Studies 19: 1669–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, D. Bondy Valdovinos, Xu Chen, and Jing Zeng. 2020. The Co-Evolution of Two Chinese Mobile Short Video Apps: Parallel Platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mobile Media & Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, Ulrike. 2013. Mastering the Art of Social Media. Information, Communication & Society 16: 717–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, Daniel. 2020. “Jump in and be Part of the Fun”. How U.S. News Providers Use and Adapt to TikTok. Paper presented at Midwest Popular Culture Association/Midwest American Culture Association Annual Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, October 1–4; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344637647_Jump_in_and_be_Part_of_the_Fun_How_US_News_Providers_Use_and_Adapt_to_TikTok (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Kosterich, Allie, and Philip M. Napoli. 2016. Reconfiguring the Audience Commodity. Television & New Media 17: 254–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018. The News User on Social Media. Journalism Studies 19: 2225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jhih-Syuan, and Jorge Peña. 2011. Are You Following Me? A Content Analysis of TV Networks’ Brand Communication on Twitter. Journal of Interactive Advertising 12: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, Donald, and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. 2020. The Epistemology of Live Blogging. New Media & Society 22: 300–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, Hallvard, Thomas Poell, and José van Dijck. 2016. Rearticulating Audience Engagement. Television & New Media 17: 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahon, Karine, Jeff Hemsley, Shawn Walker, and Muzammil Hussain. 2011. Fifteen Minutes of Fame: The Power of Blogs in the Lifecycle of Viral Political Information. Policy & Internet 3: 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navar-Gill, Annemarie. 2018. From Strategic Retweets to Group Hangs: Writers’ Room Twitter Accounts and the Productive Ecosystem of TV Social Media Fans. Television & New Media 19: 415–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreira-Rey, María-Cruz, Xosé López-García, and Lara Lozano-Aguiar. 2017. Instant Messaging Networks as a New Channel to Spread the News: Use of WhatsApp and Telegram in the Spanish Online Media of Proximity. In Recent Advances in Information Systems and Technologies. Edited by Álvaro Rocha, Ana Maria Correia, Hojjat Adeli, Luís Paulo Reis and Sandra Costanzo. Cham: Springer, pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger, Christoph, Christian Nuernbergk, and Susanne Langenohl. 2019. Journalism as Multichannel Communication. Journalism Studies 20: 1260–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Nic. 2009. The Rise of Social Media and Its Impact on Mainstream Journalism. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andi, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Nie, Liqiang, Meng Liu, and Xuemeng Song. 2019. Multimodal Learning toward Micro-Video Understanding. Synthesis Lectures on Image, Video, and Multimedia Processing 9: 1–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieborg, David B., and Thomas Poell. 2018. The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity. New Media & Society 20: 4275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen. 2020. The Nielsen Total Audience Report. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2020/the-nielsen-total-audience-report:-august-2020 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Patch, Hanna. 2018. Which Factors Influence Generation Z’s Content Selection in OTT TV?: A Case Study. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1232633&dswid=8478 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Paul, Kari. 2020. Trump’s Bid to Ban TikTok and WeChat: Where Are We Now? The Guardian. September 29. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/sep/29/trump-tiktok-wechat-china-us-explainer (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Pellicer, Miquel. 2019. TikTok: Cómo Puede Ayudar a Los Medios de Comunicación. Available online: https://miquelpellicer.com/2019/07/tiktok-como-puede-ayudar-a-los-medios-de-comunicacion/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Perrin, Andrew. 2018. Declining Share of Americans Would Find It Very Hard to Give up TV. Pew Research Center, May 3. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/03/declining-share-of-americans-would-find-it-very-hard-to-give-up-tv/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Proulx, Mike, and Stacey Shepatin. 2012. Social TV: How Marketers Can Reach and Engage Audiences by Connecting Television to the Web, Social Media, and Mobile. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Quintas-Froufe, Natalia, and Ana González-Neira. 2014. Active Audiences: Social Audience Participation in Television. Comunicar 22: 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richardson, Allissa V. 2020. The Coming Archival Crisis: How Ephemeral Video Disappears Protest Journalism and Threatens Newsreels of Tomorrow. Digital Journalism 8: 1338–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, Ana Isabel, and Rosa García-Ruíz. 2019. La Desmasificación de Los Medios de Comunicación y La Nanosegmentación Del Consumo En La Televisión Del Millennial. In La Comunicación En El Escenario Digital. Actualidad, Retos y Prospectivas. Edited by Luis Miguel Romero-Rodríguez and Diana Elizabeth Rivera-Rogel. Naucalpan de Juárez: Pearson, pp. 599–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Sharon Marie. 2008. Beyond the Box. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, Ramón, and Mathias-Felipe De-Lima-Santos. 2020. Towards Ubiquitous Journalism: Impacts of IoT on News. In Journalistic Metamorphosis. Edited by Jorge Vázquez-Herrero, Sabela Direito-Rebollal, Alba Silva-Rodríguez and Xosé López-García. Cham and Suiza: Springer, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Christine. 2019. Meet TikTok: How the Washington Post, NBC News, and The Dallas Morning News Are Using the of-the-Moment Platform. NiemanLab. June 18. Available online: https://bit.ly/2WsybF4 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Sensor Tower. 2020a. TikTok Was Installed More Than 738 Million Times in 2019, 44% of Its All-Time Downloads. January 16. Available online: https://sensortower.com/blog/tiktok-revenue-downloads-2019 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Sensor Tower. 2020b. TikTok Crosses 2 Billion Downloads After Best Quarter for Any App Ever. April 29. Available online: https://sensortower.com/blog/tiktok-downloads-2-billion (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Sidorenko-Bautista, Pavel, José María Herranz de la Casa, and Juan Ignacio Cantero de Julián. 2020. Use of New Narratives for COVID-19 Reporting: From 360° Videos to Ephemeral TikTok Videos in Online Media. Trípodos 47: 105–22. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Alba, Xosé López, and Carlos Toural. 2017. IWatch: The Intense Flow of Microformats of ‘Glance Journalism’ That Feed Six of the Main Online Media. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72: 186–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, Nele. 2015. TV Drama as a Social Experience: An Empirical Investigation of the Social Dimensions of Watching TV Drama in the Age of Non-Linear Television. Communications 40: 219–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, Robert. 2001. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson C., and Julian Maitra. 2018. News Organizations’ Use of Native Videos on Facebook: Tweaking the Journalistic Field One Algorithm Change at a Time. New Media & Society 20: 1679–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Yu-Kei. 2016. Television’s Changing Role in Social Togetherness in the Personalized Online Consumption of Foreign TV. New Media & Society 18: 1547–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Anthony. 2015. Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest. The Journal of Individual Psychology 71: 103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M. 2017. IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy- and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood*and What That Means for the Rest of Us. New York: Atria Books. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2013. Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication 1: 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2015. Making Public Television Social? Public Service Broadcasting and the Challenges of Social Media. Television & New Media 16: 148–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez, Rubén. 2015. 5 Razones de Por Qué Los Milennials No Ven Televisión. Forbes México. Available online: https://www.forbes.com.mx/5-razones-de-por-que-los-millennials-no-ven-television (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Vázquez-Herrero, Jorge, Sabela Direito-Rebollal, and Xosé López-García. 2019. Ephemeral Journalism: News Distribution Through Instagram Stories. Social Media + Society 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez-Herrero, Jorge, María-Cruz Negreira-Rey, and Xosé López-García. 2020. Let’s Dance the News: How the News Media are Adapting to the Logic of TikTok. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2020. An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies? Digital Journalism 8: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Are Social. 2020. Digital in 2020. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2020 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Welbers, Kasper, and Michaël Opgenhaffen. 2019. Presenting News on Social Media. Digital Journalism 7: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westlund, Oscar, and Stephen Quinn. 2018. Mobile Journalism and MoJos. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Yiping, Sue Robinson, Megan Zahay, and Deen Freelon. 2020. The Evolving Journalistic Roles on Social Media: Exploring ‘Engagement’ as Relationship-Building between Journalists and Citizens. Journalism Practice, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffarano, Francesco. 2019. TikTok without Generational Prejudice. Available online: https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/12/tiktok-without-generational-prejudice/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

| 1 | October 2020. |

| Country | Profiles |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 4 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Brazil | 3 |

| Canada | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 |

| Dominican Republic | 1 |

| Finland | 1 |

| France | 10 |

| Germany | 8 |

| Hungary | 1 |

| India | 2 |

| Ireland | 1 |

| Italy | 3 |

| Jordan | 5 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Poland | 4 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Russia | 6 |

| South Korea | 3 |

| Spain | 16 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Turkey | 4 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 14 |

| United States | 37 |

| TV Channel | Profiles |

|---|---|

| General | 28 |

| News | 9 |

| Sports | 9 |

| Musical | 8 |

| Entertainment | 5 |

| Children | 3 |

| Comedy | 1 |

| TV Programme | Profiles |

|---|---|

| Talent show | 22 |

| News | 8 |

| Comedy | 8 |

| Contest | 6 |

| Reality | 7 |

| Late show | 3 |

| Educational | 2 |

| Lifestyle | 2 |

| Magazine | 2 |

| News magazine | 2 |

| Talk show | 2 |

| Zapping | 2 |

| Sports | 1 |

| Profile | Country | Followers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV Channel | Children | Nickelodeon | United States | 9.3 M |

| Comedy | Comedy Central | United States | 2.6 M | |

| Entertainment | Телеканал ТНТ | Russia | 1.4 M | |

| Generalist | Telemundo | United States | 928.7 k | |

| Musical | MTV | United States | 5.0 M | |

| News | Mirror Now | India | 191.5 k | |

| Sports | ESPN | United States | 11.7 M | |

| TV Programme | Comedy | Wild’n Out | United States | 7.8 M |

| Contest | Fear Factor | United States | 1.0 M | |

| Educational | Het Klokhuis | Netherlands | 113.7 k | |

| Late show | The Late Late Show | United States | 4.3 M | |

| Lifestyle | Follovers | Poland | 133.9 k | |

| Magazine | The Insider | United Arab Emirates | 78.7 k | |

| News | E! News | United States | 1.4 M | |

| News magazine | Today Show | United States | 205.2 k | |

| Reality | 90 Day Fiancé | United States | 1.8 M | |

| Sports | NBA on TNT | United States | 362.6 k | |

| Talent show | America’s Got Talent | United States | 5.1 M | |

| Talk show | El Hormiguero | Spain | 845 k | |

| Zapping | Zapeando | Spain | 128.9 k | |

| Digital | General | Yle Areena | Finland | 52.6 k |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vázquez-Herrero, J.; Negreira-Rey, M.-C.; Rodríguez-Vázquez, A.-I. Intersections between TikTok and TV: Channels and Programmes Thinking Outside the Box. Journal. Media 2021, 2, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2010001

Vázquez-Herrero J, Negreira-Rey M-C, Rodríguez-Vázquez A-I. Intersections between TikTok and TV: Channels and Programmes Thinking Outside the Box. Journalism and Media. 2021; 2(1):1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez-Herrero, Jorge, María-Cruz Negreira-Rey, and Ana-Isabel Rodríguez-Vázquez. 2021. "Intersections between TikTok and TV: Channels and Programmes Thinking Outside the Box" Journalism and Media 2, no. 1: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2010001