Abstract

Here, 1,6-diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles, prepared by the reaction of cyanoacethydrazide with arylmethylene malononitriles, react with 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole and chloroacetyl chloride to give corresponding cyanoacetamides and chloroacetamides. The reaction with phthalic anhydride proceeds under harsh conditions to give 4,7-dioxo-4,7-dihydropyrido[1′,2′:2,3][1,2,4]triazolo[5,1-a]isoindole- 1,3-dicarbonitriles.

1. Introduction

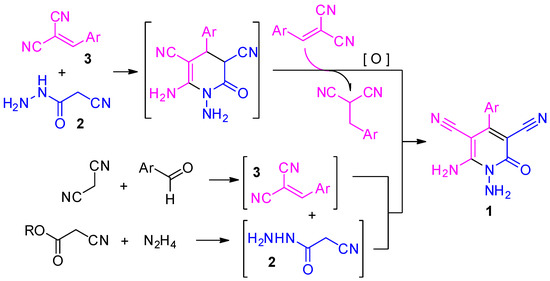

In 1981, 1,6-Diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles 1 were first prepared by Soto and colleagues through the reaction of cyanoacethydrazide 2 with two eq. arylmethylene malononitriles 3 [1] (Scheme 1). The reaction also may be performed in a multicomponent mode, using corresponding aldehyde, malononitrile and cyanoacethydrazide 2. The 1,6-diaminopyridines 1 are highly functionalized, promising reagents that can be used to build various nitrogen-bridged polyheterocyclic systems (for a review, see [2]). A survey of the literature revealed a lack of information on the reaction of 1,6-diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles 1 with functionalized acylating agents such as 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole, chloroacetyl chloride and phthalic anhydride. Consequently, we decided to fill this gap by performing the aforementioned reactions ourselves.

Scheme 1.

The preparation of 1,6-diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles 1.

2. Results and Discussion

First, we prepared a series of the starting compounds 1. We confirmed the observation of Soto and colleagues [1] that high yields of compounds 1 may be achieved only when arylmethylene malononitriles 3 are taken in at least two-fold excess with respect to cyanoacethydrazide 2. Thus, the true oxidant in the reaction is arylmethylene malononitrile 3, not atmospheric oxygen.

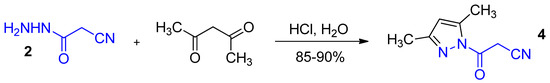

In 1957, 1-Cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole 4 (3-(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)-3-oxopropanenitrile, cyanoacetylpyrazole) was introduced into synthetic practice by Ried and Meyer [3] and, since then, it has established itself as a highly effective cyanoacetylating agent—more powerful than ethyl cyanoacetate and less impractical, stabler and more convenient than cyanoacetyl chloride. As of 2020, the chemical properties of 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole 4 have been covered in several review papers [4,5,6]. It has been prepared by a reaction of cyanoacethydrazide 2 with acetylacetone in aqueous HCl by a reported procedure [7] (Scheme 2):

Scheme 2.

The preparation of 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole 4.

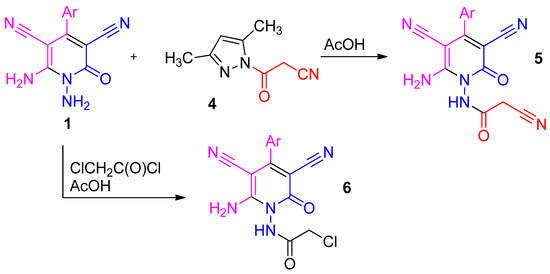

When 1,6-diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles 1 were treated with 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole 4 in hot AcOH, corresponding cyanoacetamides 5 were isolated in fair yields (Scheme 3). Similar results were observed in the reaction of 1 with chloroacetyl chloride—the products were corresponding chloroacetamides 6. Compounds 5 and 6 can be considered as promising reagents for heterocyclic synthesis.

Scheme 3.

The preparation of compounds 5 and 6.

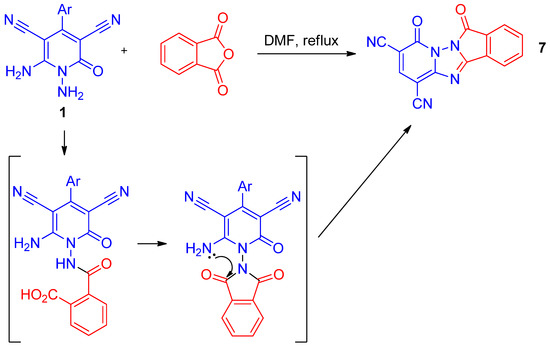

The reaction of 1,6-diaminopyridines 1 with phthalic anhydride proceeds in quite a different manner. Thus, when treated with an excess of phthalic anhydride in boiling DMF (dimethylformamide), derivatives of the new polyheterocyclic system—4,7-dioxo-4,7-dihydropyrido[1′,2′:2,3][1,2,4]triazolo[5,1-a]isoindole-1,3-dicarbonitrile 7—were isolated (Scheme 4). Presumably, the reaction started as simple acylation followed by cascade condensation to phthalimide and finally to polycyclic structure 7.

Scheme 4.

The preparation and mechanism of formation of compound 7.

3. Experimental

Preparation of Compounds 5 and 6

First, 1,6-Diamino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile 1 and 1.5 eq. 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole 4 were heated under reflux in a minimal amount of glacial AcOH. The reaction was monitored by TLC (thin-layer chromatography). After total consumption of 1, the reaction refluxed for 5 min, and the product was allowed to cool and left to stand overnight. A yellowish solid was separated, filtered off and washed with EtOH to give pure cyanoacetamides 5. A similar procedure as reported with chloroacetyl chloride afforded chloroacetamides 6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V.D.; methodology, V.V.D..; investigation, A.A.D., A.R.C., V.V.D.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V.D.; writing—review and editing, V.V.D.; supervision, V.V.D.; funding acquisition, V.V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by RFBR and administration of Krasnodar Territory, project number 20-43-235002.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Soto, J.L.; Seoane, C.; Zamorano, P.; Cuadrado, F.J. A Convenient Synthesis of N-Amino-2-pyridones. Synthesis 1981, 7, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; El-Gohary, N.M. Heterocyclization with Some Heterocyclic Diamines: Synthetic Approaches for Nitrogen Bridgehead Heterocyclic Systems. Heterocycles 2014, 89, 1125–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, W.; Meyer, A. Über die Verwendung von Cyanacethydrazid zur Darstellung von Stickstoffheterocyclen, I. Eine Einfache Synthese von N-Amino-α-Pyridonen. Chem. Berichte 1957, 90, 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigorina, E.A.; Dotsenko, V.V. 1-Cyanoacetyl-3, 5-dimethylpyrazole–effective cyanoacetylating agent and a new building block for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2012, 48, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigorina, E.A. 1-Cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole. Synlett 2014, 25, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigorina, E.A.; Dotsenko, V.V. Novel reactions of 1-cyanoacetyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazole. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2020, 56, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorobets, N.Y.; Yousefi, B.H.; Belaj, F.; Kappe, C.O. Rapid microwave-assisted solution phase synthesis of substituted 2-pyridone libraries. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 8633–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).