1. Introduction

Brain–computer interface (BCI) technology enables direct communication between neural activity and external devices, bypassing muscular pathways [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. BCIs can restore autonomy and interaction for individuals with severe motor disabilities by converting brain signals into actionable commands for assistive systems [

6,

7,

8]. Among available modalities, electroencephalography (EEG) remains the most prevalent due to its noninvasive nature, low cost, portability, and high temporal resolution [

9,

10]. EEG-based BCIs have demonstrated potential in rehabilitation, prosthesis control, and assistive mobility applications such as robotic or electric wheelchairs [

11,

12]. Despite these advancements, translating EEG-based BCIs from laboratory prototypes to daily assistive use remains challenging because of environmental noise, signal variability, and user-specific calibration requirements [

13,

14,

15].

The present study focuses on the development of a steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP)-based BCI system designed to control an electric wheelchair integrated with a speech aid module [

16,

17]. Such systems aim to support individuals affected by neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple sclerosis (MS), where progressive loss of motor function severely limits mobility and communication [

18]. According to clinical statistics, the prevalence of ALS is approximately 1.9 per 100,000 people, with an expected 69% increase over the next 25 years [

19]. Conventional joystick-operated wheelchairs are unsuitable for these patients, emphasizing the need for non-muscular control strategies. Integrating SSVEP-based BCI control with speech output can provide both mobility and communication, addressing two key aspects of patient autonomy [

20,

21,

22]. Previous studies on motor imagery (MI) paradigms for wheelchair or speller control achieved limited accuracy and required long calibration sessions [

23,

24]. In contrast, steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP)-based BCIs have gained prominence due to their high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), fast response time, and reduced training requirements [

25,

26,

27].

Traditional SSVEP classification methods, such as Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and its variants, have long served as benchmarks for frequency recognition due to their simplicity and robustness [

26,

28]. However, these techniques rely primarily on handcrafted features and linear correlations, which limit their performance in complex or noisy real-world environments [

23,

29]. To overcome these challenges, researchers have increasingly turned to deep learning, leveraging convolutional and hybrid neural architectures to automatically extract discriminative spatiotemporal features from EEG data. For instance, Ikeda (2021) proposed a complex-valued CNN to overcome the limitation of SSVEP-based BCIs [

30]. Israsena et al. (2022) developed a CNN network for SSVEP detection targeting binaural ear-EEG [

31]. Wan et al. (2023) introduced a transformer–based brain activity classification method using EEG signals [

32]. Beyond SSVEP signal processing, related works have applied deep architectures such as EEGNet, residual networks, and graph neural networks to diverse BCI tasks, demonstrating the adaptability of these models for EEG feature extraction and classification [

33]. Recent hybrid and enhanced paradigms, such as P300–SSVEP combinations [

34] and cloud-connected systems using compressive sensing for data efficiency [

35], have also demonstrated improved information transfer rates (ITR) exceeding 100 bits/min, highlighting the feasibility of real-world BCI operation. Several recent studies have also integrated SSVEP-driven BCIs with assistive technologies such as robotic or electric wheelchairs and communication systems. Rivera-Flor et al. (2022) employed compressive sensing to enhance SSVEP command decoding for a robotic wheelchair, while Sakkalis et al. (2022) combined augmented reality with SSVEP paradigms to improve user interaction [

21,

35].

In summary, the literature demonstrates rapid advancement in deep learning–based SSVEP analysis and its translation into assistive applications. However, most existing studies focus either on algorithmic improvement or on a single application domain. The integration of an SSVEP-based deep learning system capable of performing dual functions—wheelchair control and speech aid—remains largely unexplored. The motivation for this research arises from the need for a practical, real-time assistive interface that minimizes user training and electrode complexity while maintaining robustness against interference. Addressing this research gap constitutes the main novelty and contribution of the present work. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the experimental design, including the stimulus interface, EEG acquisition, preprocessing, and classification models.

Section 3 presents the results and discussion of the real-time testing of the proposed system. Finally,

Section 4 concludes the paper by summarizing the findings and outlining future research directions.

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Overall Description

The proposed system integrates multiple functional modules that collectively enable brain-signal-driven control of both wheelchair movement and speech output. It comprises an SSVEP stimulus interface, an EEG acquisition and preprocessing unit, a classification module, and a hardware control system managed by an Arduino microcontroller.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall system architecture, showing the signal flow from visual stimulus generation to actuation. The flickering SSVEP interface elicits EEG responses from the occipital region, which are recorded by gold cup electrodes, filtered, and processed to extract relevant features. The classified outputs are transmitted to the Arduino microcontroller, which converts them into corresponding control signals to drive the wheelchair motors or activate the speech module. This integrated setup enables users with severe motor impairments to control mobility and communication functions through brain activity alone.

All modules are mounted on board to facilitate the wheelchair’s mobility. The SSVEP display is positioned close to the user’s eyes to ensure high recognition accuracy and ease of use. The system operates by capturing visual-evoked EEG signals, processing them to enhance their quality, classifying them into predefined commands, and executing those commands via the microcontroller.

The proposed system consists of four primary modules: the stimulus interface, EEG signal acquisition and preprocessing, classification using machine learning models, and the hardware control system for the wheelchair and speech aid. The following subsection provides details on each component and their interconnections.

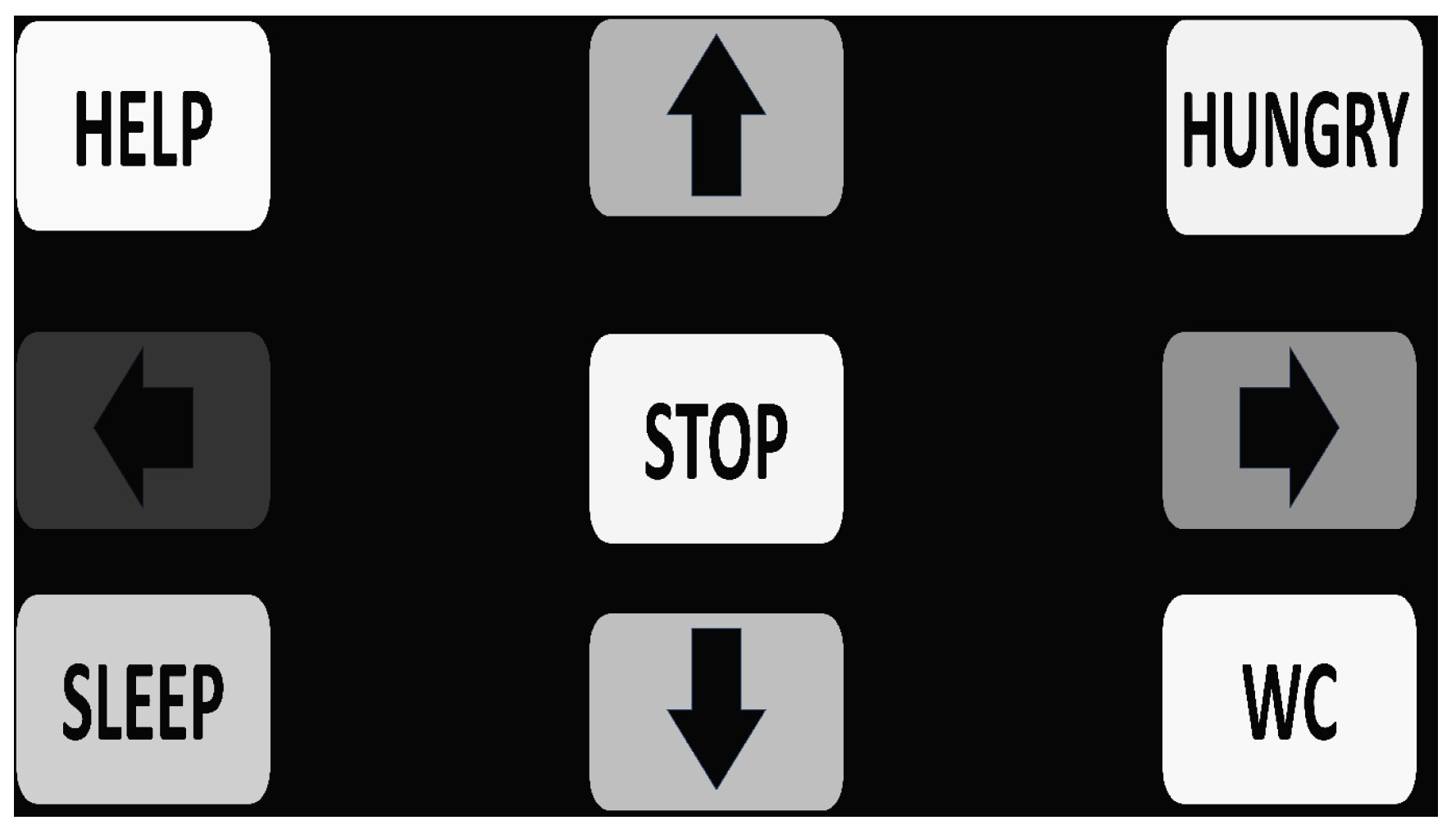

2.2. Stimulus Design

Nine flickering stimuli with distinct frequencies ranging from 7.5 Hz to 14.87 Hz were displayed on a 15.6-inch LED screen in a 3 × 3 grid. Five frequencies were assigned to motion commands (forward, backward, left, right, stop), and four were assigned to essential speech commands (hungry, sleep, help, WC). The stimuli were designed to evoke SSVEP responses in the user’s occipital cortex. On a 15.6-inch LED monitor with a refresh rate of 60 Hz and a resolution of 1366 × 768 pixels, a total of nine stimuli were presented (

Figure 2). The associated flicker frequencies for each stimulus were: 7.50 Hz: forward, 8.42 Hz: hungry, 9.37 Hz: left, 9.96 Hz: stop, 10.84 Hz: right, 11.87 Hz: sleep, 12.5 Hz: backward, 13.4 Hz: WC, and 14.87 Hz: help, as shown in

Figure 3. These frequencies were selected based on earlier SSVEP research [

25,

36]. The stimuli were arranged in a 3×3 matrix resembling a phone’s virtual keypad. The horizontal and vertical distances between two adjacent stimuli were 7.5 cm and 1.5 cm, respectively. The Interface2app application was used to develop and implement the flickering stimuli. To maintain system simplicity, the command words were kept brief and limited in number. The selection of the 7.5–14.87 Hz frequency range was further justified based on SSVEP response characteristics in the occipital alpha band, where visual-evoked potentials are strongest and most stable. The chosen frequencies are harmonically distinct, evenly spaced to reduce inter-frequency interference, and synchronized with the 60 Hz refresh rate of the display (integer frame multiples), ensuring phase stability and reliable flicker generation. This design choice aligns with established SSVEP literature and supports robust signal acquisition for real-time classification.

2.3. Signal Acquisition

When choosing hardware and software components for the EEG-based BCI, various factors were considered. The goal was to find a compact and portable solution for BCI control. Gold cup electrodes from Neuroelectrics were selected to acquire the EEG signals. These electrodes are specifically designed for BCI research and offer wireless technology and wet electrodes, simplifying the experimental setup.

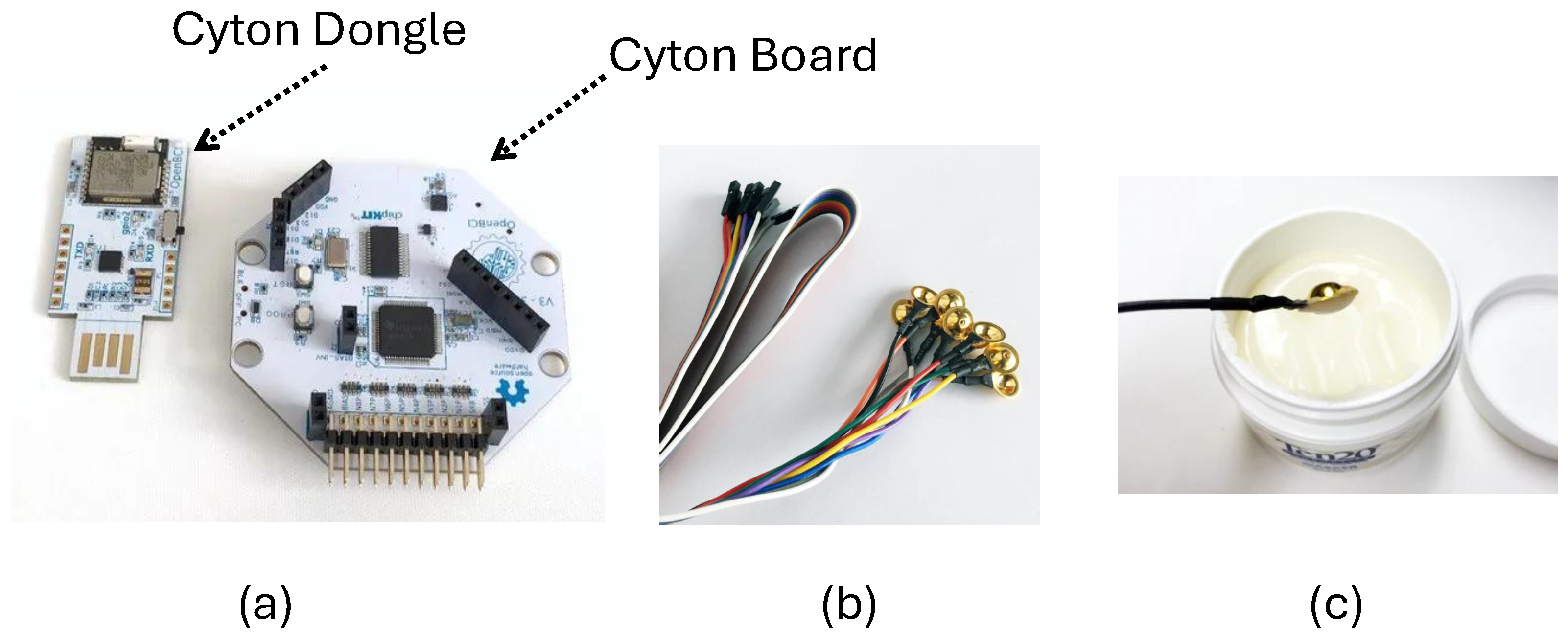

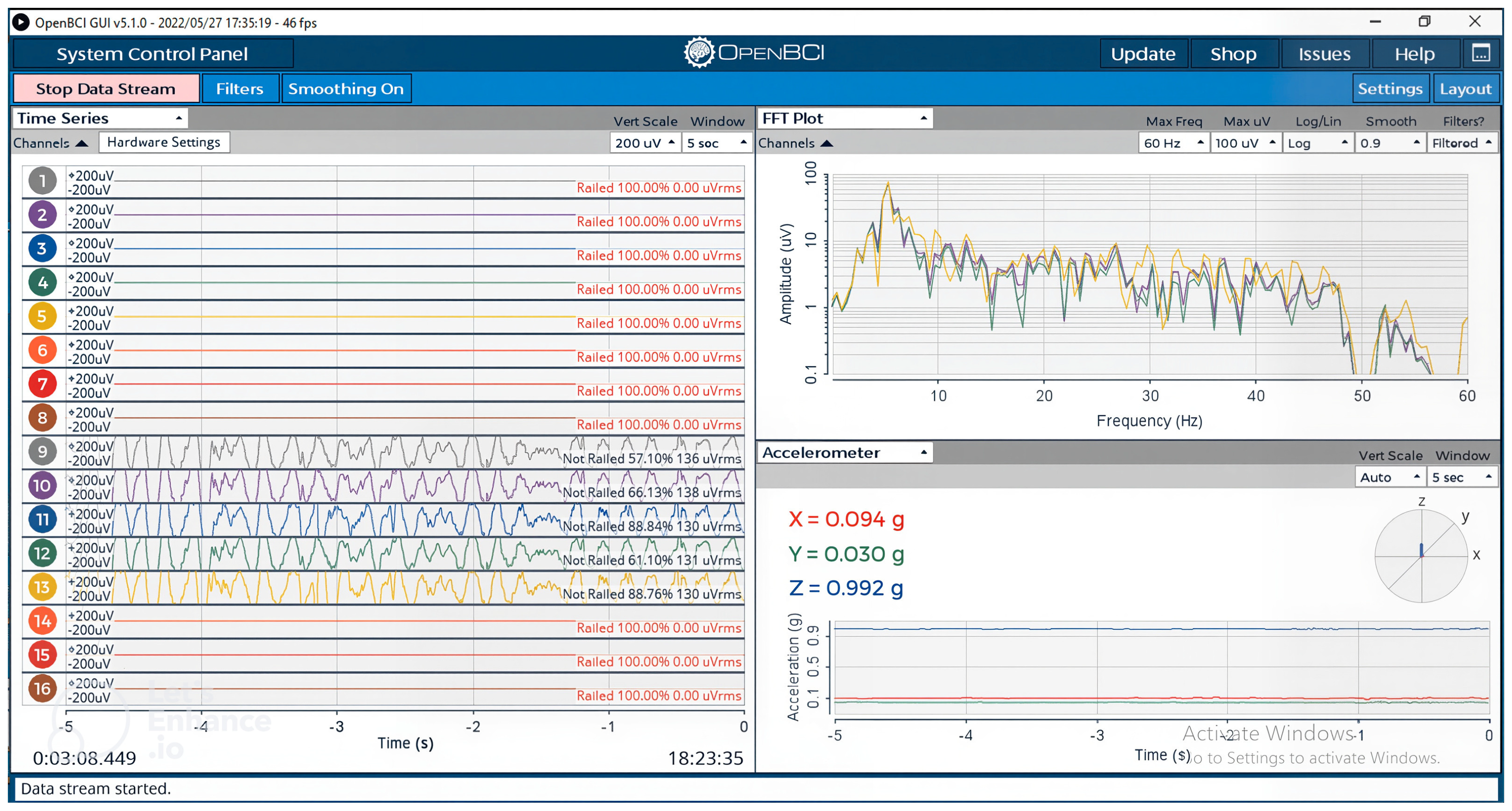

EEG data acquisition was performed using the OpenBCI hardware setup shown in

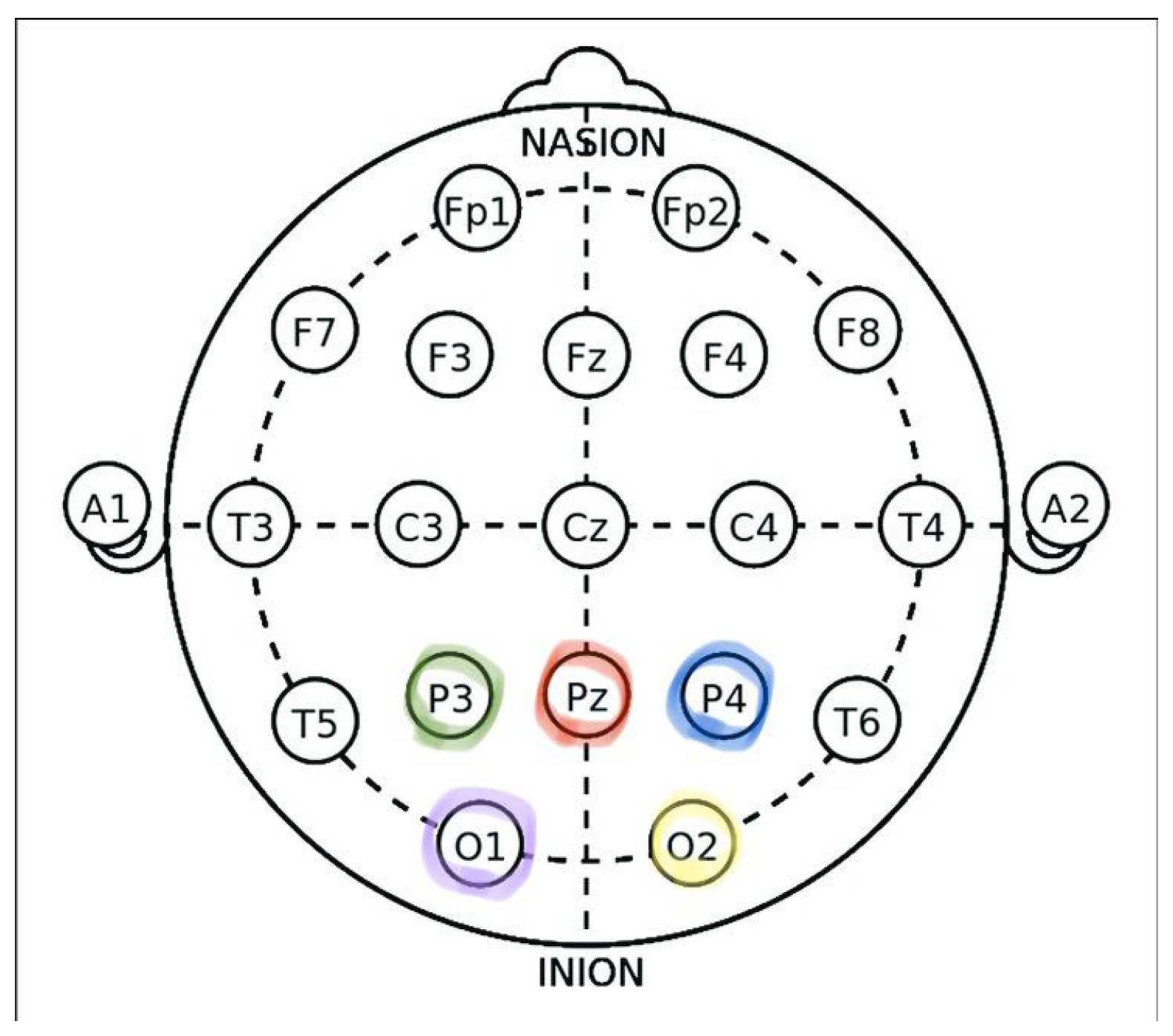

Figure 4. The system consists of a Cyton board and a Cyton dongle for wireless data transmission, gold-cup electrodes, and conductive electrode cap gel used to maintain proper scalp contact. The Cyton board amplified and digitized the EEG signals, while the Cyton dongle transmitted them to the computer via Bluetooth for real-time monitoring and recording. The electrodes were securely attached to the scalp using the electrode gel to ensure low impedance and stable signal quality. EEG signals were recorded from five channels (O1, O2, Pz, P3, and P4) positioned over the occipital region according to the international 10–20 system, as illustrated in

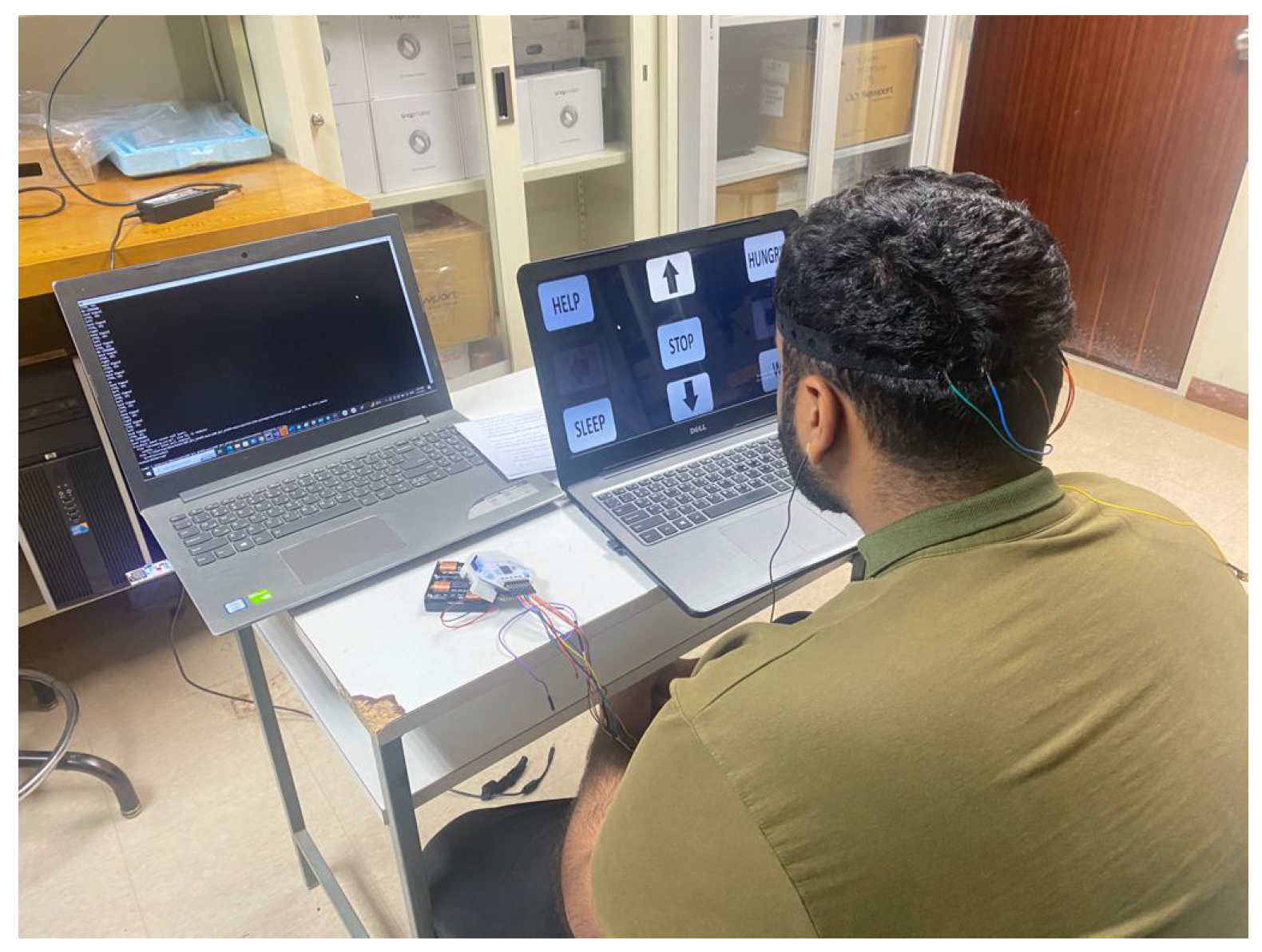

Figure 5, where the colored markers indicate the electrode locations used for EEG recording. Electrodes A1 and A2 served as references. This electrode configuration was chosen to effectively capture visual-evoked responses associated with SSVEP stimuli. The complete experimental setup is shown in

Figure 6. The participant sat approximately 60 cm from the SSVEP stimulus screen while connected to the OpenBCI recording system. The EEG signals were displayed in real time using the OpenBCI GUI to verify impedance levels and signal quality, as shown in

Figure 7. Once stable readings were achieved, visual flickering stimuli were presented to evoke SSVEP responses, which were then processed and classified to generate corresponding wheelchair or speech commands.

2.4. Signal Preprocessing

To extract useful features from the recorded EEG signals, processing and filtering were applied.

The visual flashing frequencies in this design ranged from 7.5 to 14.7 Hz, primarily associated with alpha waves. After testing various ranges, the maximum frequency was kept low to avoid aliasing and to maximize frequency spacing between stimuli.

First, a 60 Hz notch filter was applied to remove power-line interference, rather than EMG noise. Next, a second-order Chebyshev bandpass filter with a ripple of 0.3 dB was applied over the 7–15 Hz range to isolate the frequencies of interest.

Figure 8 shows the FFT spectrum of recorded EEG signals ready for classification. Each of the nine signals displayed a distinctive spike at the target frequency, making them recognizable for the classifiers.

2.5. Classification Models

Four different classification techniques were examined to determine the most suitable one for this design. Due to the scarcity of standard datasets, transfer learning was employed to save training time, improve the performance of neural networks, and reduce the need for large amounts of data. Instead of starting the learning process from scratch, transfer learning allowed leveraging patterns learned from solving a related task. All deep learning networks (ResNet50, VGG16, and InceptionV4) were initialized with ImageNet-pretrained weights. The final classification layers were replaced and fine-tuned using the recorded EEG dataset for nine SSVEP classes, employing a learning rate of 1 × 10–4 and an early-stopping strategy to prevent overfitting. Deep learning networks and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) were the two main approaches considered. Therefore, a comparison between three deep learning networks (ResNet50, VGG16, InceptionV4) and CCA was conducted to identify the most suitable classifier.

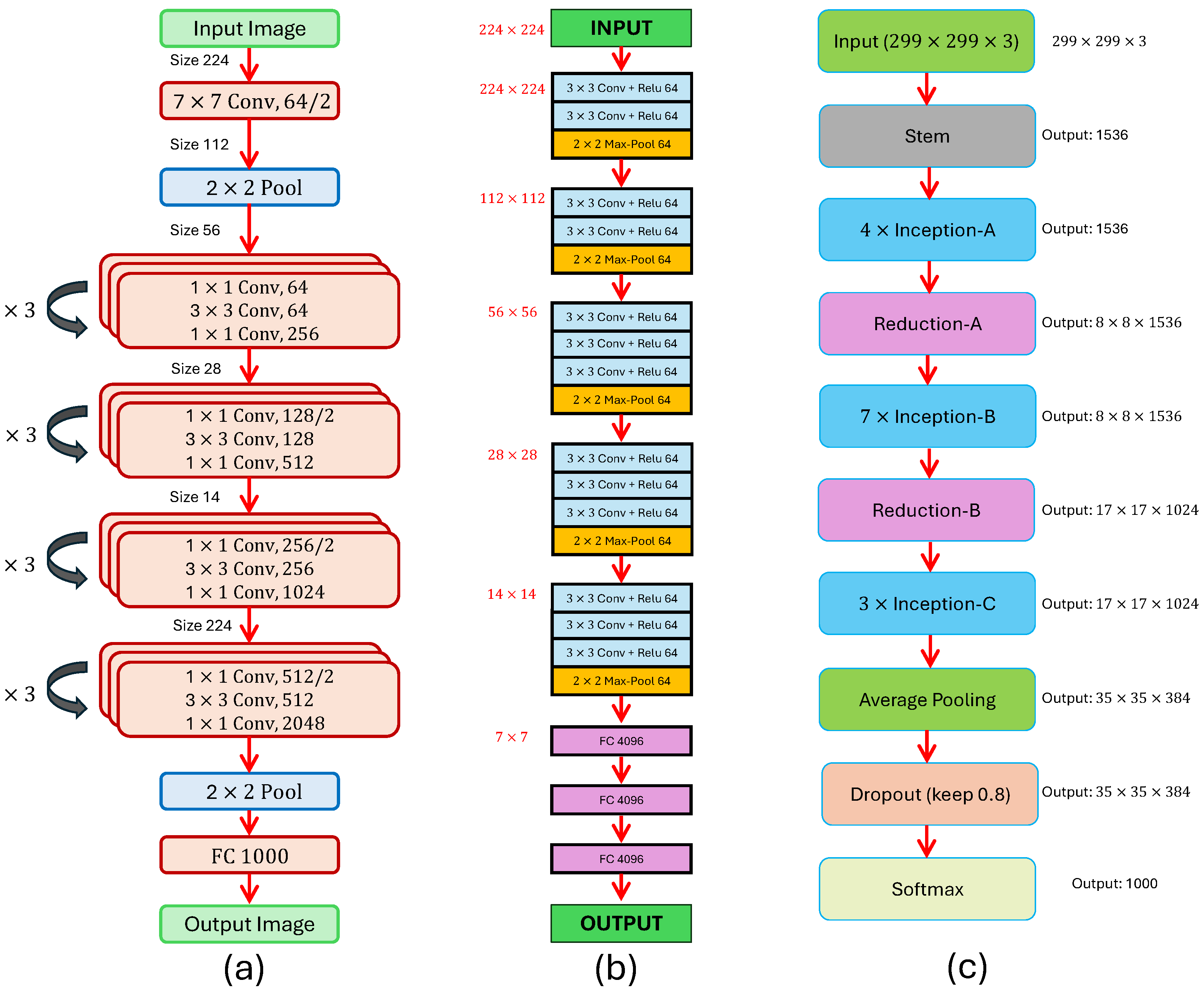

2.5.1. ResNet50

ResNet50, introduced by He et al. in 2016 [

37], is a 50-layer convolutional neural network (CNN), which builds networks by stacking residual blocks. The architecture is composed of 48 convolutional layers, one MaxPool layer, and one average pool layer, as shown in

Figure 9a. The earlier ResNet architecture, ResNet34, introduced shortcut connections to add extra convolutional layers without the vanishing gradient problem. The 50-layer ResNet employs a bottleneck design using 1 × 1 convolutions to reduce the number of parameters, allowing faster training.

2.5.2. VGG16

VGG16, introduced by Simonyan and Zisserman in 2015 [

38], is a CNN that achieved 92.7% test accuracy on the ImageNet dataset containing over 14 million images. The structure comprises 13 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers (

Figure 9b). The first layers use 64 filters of size 3 × 3, followed by max pooling, then stacks of 128, 256, and 512 convolutional filters, each separated by pooling layers.

2.5.3. InceptionV4

InceptionV4, introduced by Szegedy in 2016 [

39], advanced CNN design by employing engineered modules rather than simply stacking layers. The Inception module applies convolution using multiple filter sizes (1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5) and max pooling in parallel, followed by concatenation of outputs. To reduce computation, 1 × 1 convolutions are applied before larger filters. This architecture (

Figure 9c) improves both accuracy and speed compared to earlier CNNs such as VGGNet.

2.5.4. Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)

CCA determines the oscillation frequency that correlates most strongly with the observed EEG signal. The algorithm receives selected EEG channels along with sine and cosine reference signals at each flashing frequency. The sinusoid with the highest correlation is chosen, and the associated command is transmitted to the microcontroller.

Mathematically, given two sets of variables

X and

Y, CCA seeks weight vectors

and

that maximize the correlation between their linear combinations:

Here,

X is the multichannel EEG data, and

is the set of reference signals defined as:

where

is the number of harmonics,

the stimulus frequency, and

the sampling frequency. The SSVEP frequency is estimated as the one yielding the maximum canonical correlation.

2.6. Results of Classification Models

To determine the best classifier, all four models were tested on a dataset collected from four healthy male subjects (average age 23, normal vision). EEG signals were recorded using five gold-cup electrodes over the occipital area, connected to a Cyton board. Signals were sampled at 125 Hz, referenced to A1 and A2.

Participants were seated 60 cm from the monitor in a dimly lit room. Each subject completed 90 blocks, with 9 trials per block (6 s gaze per trial). The dataset was split 80/20 into training and testing sets. Models were trained in TensorFlow 2.11.0 using an NVIDIA® GeForce RTX 3050 Laptop GPU acceleration (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The EEG signals were categorized into nine classes corresponding to commands. Models were evaluated using mean average precision (mAP), average recall (AR), and F1-score.

Although several recent EEG feature learning networks such as EEGNet have demonstrated excellent performance on benchmark datasets, we did not include EEGNet in this comparative analysis. EEGNet requires extensive dataset-specific tuning of temporal and spatial convolution parameters to achieve optimal performance, which limits its direct transferability across hardware configurations. Since our study involved only five occipital channels and a relatively small dataset, we prioritized benchmarking transfer-learning-based CNN models (ResNet50, VGG16, InceptionV4) against the conventional CCA method within a consistent preprocessing and evaluation framework. Future work will consider EEGNet and other specialized architectures for extended comparison.

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

Performance was assessed using the following metrics:

Precision , the fraction of correctly classified positive samples.

Mean Average Precision (mAP): Average of class-wise precisions across all classes.

Average Recall (AR), the average fraction of actual positives correctly detected.

F1-Score: , the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

2.8. Performance Summary

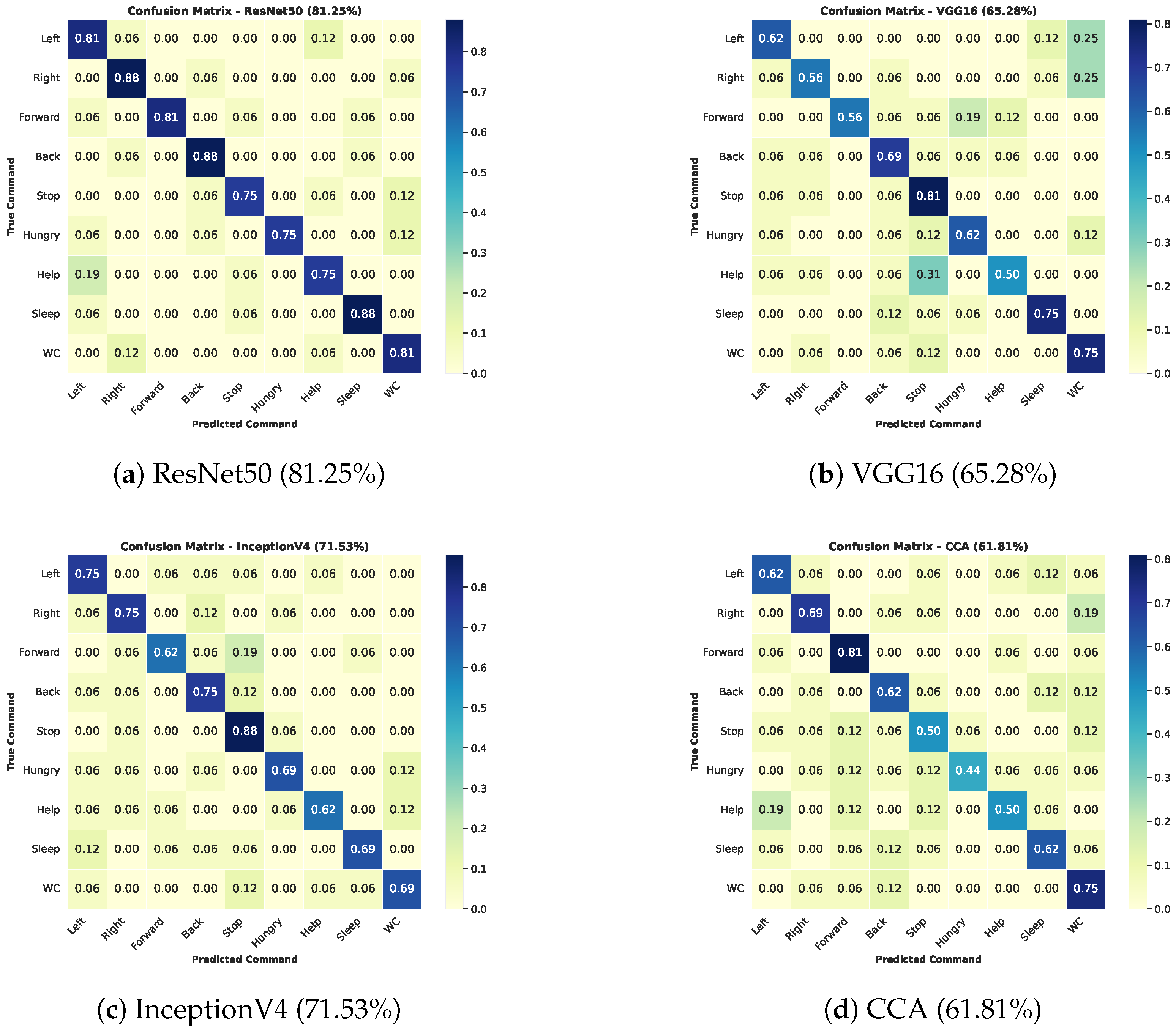

Figure 10 and

Table 1 summarize the results. ResNet50 achieved the highest mAP (0.82) and AR (0.77), indicating superior accuracy and fewer false positives. InceptionV4 performed reasonably well (mAP 0.72), followed by CCA and VGG16. VGG16 showed higher recall than CCA, suggesting better sensitivity but slightly lower precision. ResNet50 exhibited strong diagonal dominance in its confusion matrix, demonstrating consistent classification across all commands. Therefore, ResNet50 was chosen for real-time implementation.

3. Results and Discussion

After finalizing the classification approach and identifying ResNet50 as the most effective model, the next phase involved developing a physical implementation to evaluate the system in a real-world scenario. A 3D-printed wheelchair model was fabricated for this purpose, and the full control system was built using Arduino hardware.

The classified signals were transmitted via Bluetooth to an Arduino Uno microcontroller, which directed four DC motors for wheelchair movement or triggered audio playback from a connected speaker. Audio files were stored on a micro SD card, and an ultrasonic sensor ensured obstacle avoidance within a 15 cm detection range. The wheelchair’s movement was limited to four directions with 90-degree turns for operational simplicity, while the speech aid was implemented using a speaker module activated by the classified brain commands.

Figure 11 shows the hardware integration of the Arduino board with the motors, speaker, and ultrasonic sensor.

The 3D-printed wheelchair prototype was designed using Tinkercad and fabricated with a Snapmaker 3D printer. The model incorporated the motorized base, Arduino controller, and speaker system to validate real-time control and speech output. The final prototype is shown in

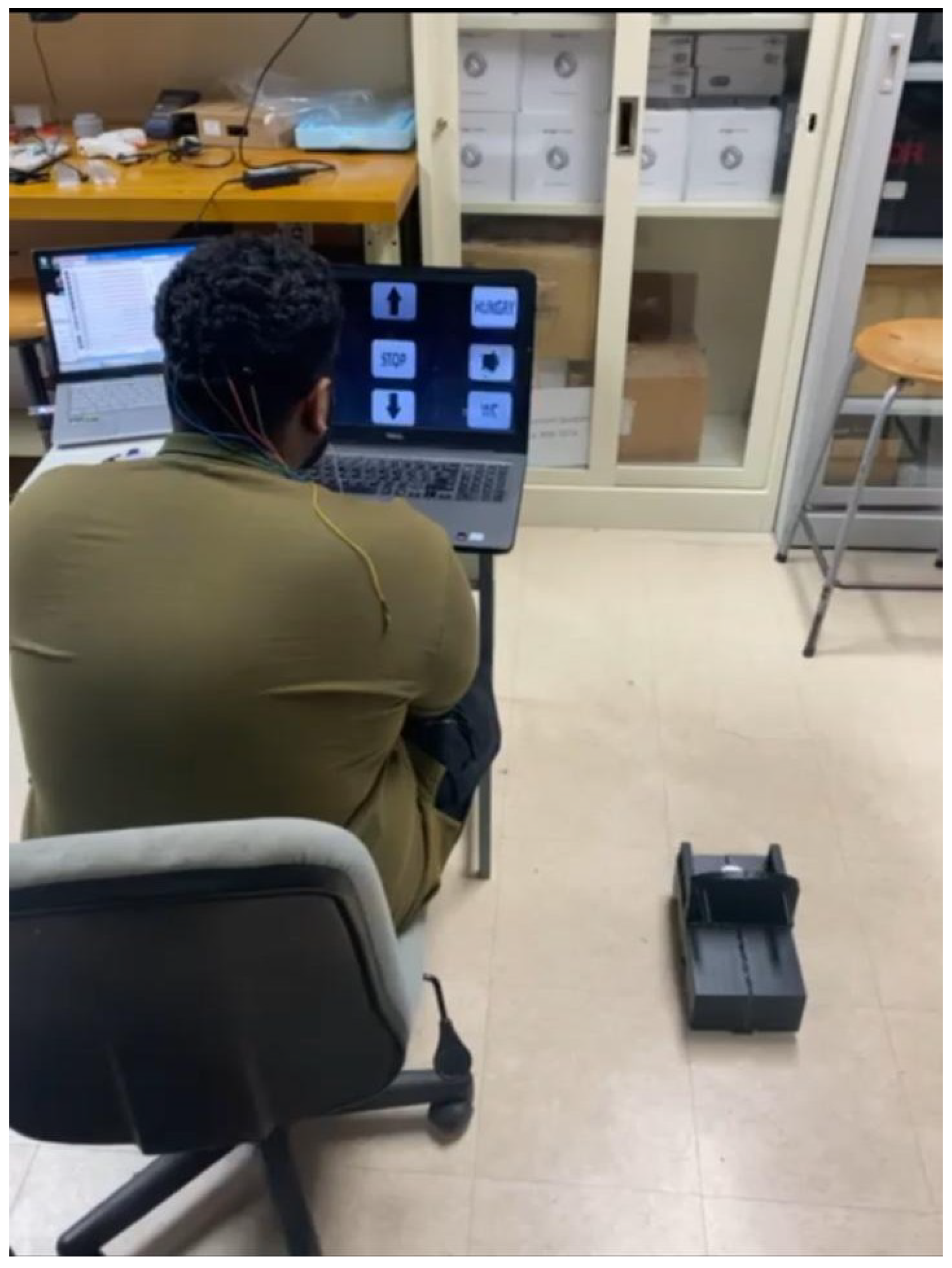

Figure 12. Testing was conducted with four healthy male participants (average age 23 years) in a dimly lit, controlled laboratory environment to ensure consistent visual stimulus perception and minimize external distractions. The purpose of this preliminary experiment was to validate the functional operation of the proposed SSVEP-based BCI system before future trials with motor-impaired participants. Each participant provided informed consent prior to testing. The real-time testing evaluated the system’s end-to-end performance, encompassing EEG acquisition, signal preprocessing, classification, and physical actuation of the wheelchair and speech modules.

EEG signals were acquired using the OpenBCI Cyton board with five wet gold-cup electrodes positioned over the occipital region (O1, O2, Pz, P3, P4) according to the 10–20 system. The signals were sampled at 125 Hz, referenced to A1 and A2, and transmitted wirelessly via Bluetooth to a laptop for processing. A 15.6-inch LED monitor (refresh rate: 60 Hz; resolution: 1366 × 768) displayed nine flickering stimuli representing movement and speech commands. Participants were seated 60 cm from the screen and instructed to focus their gaze on a target stimulus corresponding to the desired command, as shown in

Figure 13. During testing, EEG signals were processed in real time through a notch filter (60 Hz) and a bandpass filter (7–15 Hz) before being classified using the ResNet50 model. The classified outputs were transmitted to an Arduino microcontroller that executed the corresponding wheelchair or speech command. Classification predictions were simultaneously displayed on screen and logged for post-analysis.

To generate the confusion matrix, each participant completed a series of 50 trials per command. In each trial, the participant was instructed to focus on one of the four directional flickers (forward, backward, left, or right) for 10 s while the system recorded and classified the corresponding EEG response. The system’s output was compared to the intended command to determine whether it was correctly recognized. For each participant, accuracy was calculated as the ratio of correctly classified commands to the total number of trials. The final confusion matrix was obtained by averaging the classification accuracy of all four participants for each command, allowing visualization of both correct and misclassified responses across the four control categories.

Figure 14 presents the confusion matrix obtained from the aggregated results of all participants. The ResNet50 classifier achieved an overall real-time accuracy of 72.44%, with individual command accuracies ranging from 69.8% to 77.8%. Derived statistical metrics included a mean precision of 0.74, recall of 0.72, and F1-score of 0.73, confirming consistent classification across the four directional commands (forward, backward, left, right).

To compare the proposed system with the state of the art, this paragraph will discuss its performance compared to recent SSVEP-based BCI studies. Unlike the systems of [

30,

32], which achieved high classification accuracies (approximately 80–90%) under offline or simulated conditions, the proposed model demonstrated comparable performance with an offline accuracy of 81.25% and a real-time accuracy of 72.44%. In contrast to [

21,

35], whose SSVEP-based assistive systems were limited to wheelchair control, the presented design provides dual functionality—enabling both mobility and speech assistance. Furthermore, the system attains these results using only five occipital electrodes, significantly reducing setup complexity and calibration time compared to multi-channel configurations (8–32 electrodes) adopted in most existing approaches. This combination of real-time deep learning implementation, minimal hardware, and dual control capability highlights the novelty and practical advantage of the proposed system.

The results validate the feasibility of using the proposed SSVEP–ResNet50 framework for real-time control tasks. However, this functional test was limited to healthy subjects and a small sample size, which constrains generalization to end users with motor disabilities. Future work will include clinical trials with motor-impaired participants, expanded datasets, and adaptive calibration algorithms to enhance cross-user reliability. Overall, the combination of wet electrodes, the SSVEP paradigm, and deep learning classification proved effective in enabling simultaneous communication and mobility control, showing strong potential for real-world assistive applications.

4. Conclusions

This paper presented a functional prototype of an SSVEP-based brain–computer interface (BCI) system designed to enable both mobility and basic communication through integrated wheelchair and speech aid control. EEG signals were acquired from the occipital region using wet gold-cup electrodes and processed through deep learning classifiers, with ResNet50 achieving the highest offline accuracy of 81.25% and a real-time performance of 72.44%. The inclusion of a speech output module alongside directional control verified the dual functionality of the system in real-time testing with healthy participants. The 3D-printed prototype, powered by Arduino microcontrollers, successfully demonstrated reliable end-to-end operation—spanning EEG acquisition, preprocessing, classification, and command execution—under live conditions. While the proposed system proved technically feasible, several limitations must be acknowledged. The current study involved only four healthy participants, which restricts statistical generalization. Tests were performed in a controlled environment rather than clinical settings, and no motor-impaired users were included. In addition, the command set and environmental complexity were limited to ensure proof-of-concept validation. These factors will be addressed in future work through expanded participant testing, inclusion of clinical trials, and implementation of adaptive algorithms to improve robustness and user-specific calibration.By demonstrating a real-time, low-cost, and dual-function SSVEP–based interface, this work contributes to the foundation of practical, non-invasive BCI systems. Future research will focus on overcoming the identified limitations to enhance usability and confirm the system’s potential for real-world assistive applications.