Use of Actigraphy for a Rat Behavioural Sleep Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

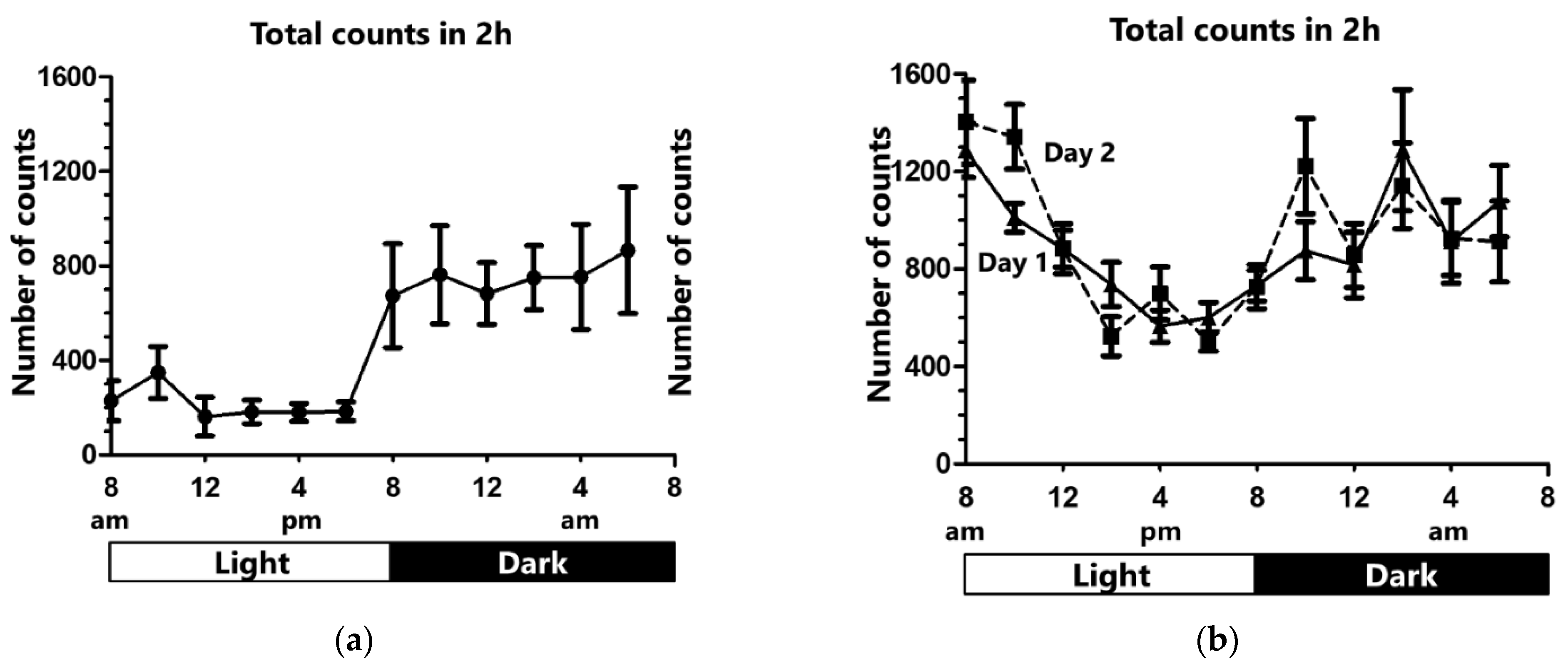

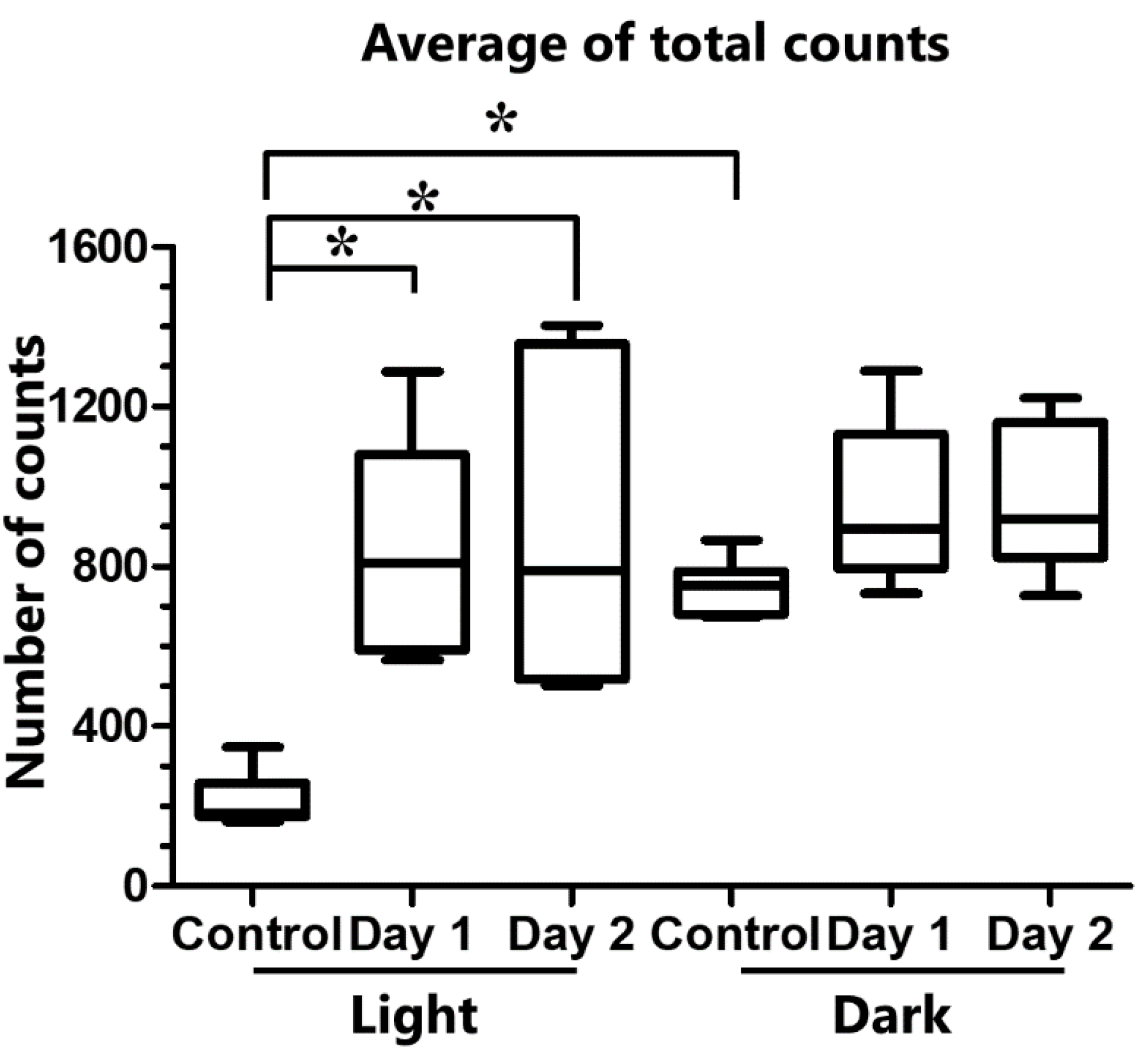

2.1. Activity under Control Condition

2.2. Activity under Sleep Deprivation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Actigraphy

4.2. Animals

4.3. Sleep Deprivation Cages

4.4. Activity under Control Conditions and Sleep Deprivation

4.5. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levenson, J.C.; Troxel, W.M.; Begley, A.; Hall, M.; Germain, A.; Monk, T.H.; Buysse, D.J. A quantitative approach to distinguishing older adults with insomnia from good sleeper controls. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Croft, J.B.; Wheaton, A.G.; Perry, G.S.; Chapman, D.P.; Strine, T.W.; McKnight-Eily, L.R.; Presley-Cantrell, L. Association between perceived insufficient sleep, frequent mental distress, obesity and chronic diseases among US adults, 2009 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minkel, J.D.; McNealy, K.; Gianaros, P.J.; Drabant, E.M.; Gross, J.J.; Manuck, S.B.; Hariri, A.R. Sleep quality and neural circuit function supporting emotion regulation. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, T.; Jha, S.K. Sleep deprivation impairs consolidation of cued fear memory in rats. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Machado, R.B.; Tufik, S.; Suchecki, D. Role of corticosterone on sleep homeostasis induced by REM sleep deprivation in rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCoy, J.G.; Christie, M.A.; Kim, Y.; Brennan, R.; Poeta, D.L.; McCarley, R.W.; Strecker, R.E. Chronic sleep restriction impairs spatial memory in rats. Neuroreport 2013, 24, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nelson, A.B.; Faraguna, U.; Zoltan, J.T.; Tononi, G.; Cirelli, C. Sleep patterns and homeostatic mechanisms in adolescent mice. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Languille, S.; Lamberty, Y.; Babiloni, C.; Perret, M.; Bordet, R.; Blin, O.J.; Jacob, T.; Auffret, A.; Schenker, E.; et al. Sleep deprivation impairs spatial retrieval but not spatial learning in the non-human primate grey mouse lemur. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrivelan, R.; Fuller, P.M.; Yokota, S.; Lu, J.; Saper, C.B. Metabolic effects of chronic sleep restriction in rats. Sleep 2012, 35, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal, M.M.; Wilkinson, F.L.; Cooper, J.D.; Wraith, J.E.; Wynn, R.; Bigger, B.W. Circadian rhythm and suprachiasmatic nucleus alterations in the mouse model of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 209, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.L.; Minassian, A.; Young, J.W.; Paulus, M.P.; Geyer, M.A.; Perry, W. Cross-species assessments of motor and exploratory behavior related to bipolar disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, S.G.; Paletz, E.M.; Obermeyer, W.H.; Hannan, C.T.; Benca, R.M. Seasonal influences on sleep and executive function in the migratory White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii). BMC Neurosci. 2010, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, J.L.; Hakim, A.D. Wrist actigraphy. Chest 2011, 139, 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Sakurai, E.; Kuramasu, A.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Okamura, N.; Zhang, D.; Yoshikawa, T.; Watanabe, T.; Yanai, K. Roles of hypothalamic subgroup histamine and orexin neurons on behavioral responses to sleep deprivation induced by the treadmill method in adolescent rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 114, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bert, J.; Pegram, V.; Rhodes, J.M.; Balzano, E.; Naquet, R. A comparative sleep study of two Cercopithecinae. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1970, 28, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.S.; Tobler, I. Animal sleep: A review of sleep duration across phylogeny. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1984, 8, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Coss, R.G. A comparison of the sleeping behavior of three sympatric primates. a preliminary report. Folia Primatol. 2001, 72, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sri Kantha, S.; Suzuki, J.; Hirai, Y.; Hirai, H. Behavioral sleep in captive owl monkey (Aotus azarae) and squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis). Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2009, 69, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Zhdanova, I.V.; Geiger, D.A.; Schwagerl, A.L.; Leclair, O.U.; Killiany, R.; Taylor, J.A.; Rosene, D.L.; Moss, M.B.; Madras, B.K. Melatonin promotes sleep in three species of diurnal nonhuman primates. Physiol. Behav. 2002, 75, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, C.E.; Lajos, L.E.; Waters, W.F. Wrist actigraph versus self-report in normal sleepers: Sleep schedule adherence and self-report validity. Behav. Sleep Med. 2004, 2, 134–143, discussion 144–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedner, J.; Pillar, G.; Pittman, S.D.; Zou, D.; Grote, L.; White, D.P. A novel adaptive wrist actigraphy algorithm for sleep-wake assessment in sleep apnea patients. Sleep 2004, 27, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadeh, A.; Acebo, C. The role of actigraphy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- So, K.; Adamson, T.M.; Horne, R.S. The use of actigraphy for assessment of the development of sleep/wake patterns in infants during the first 12 months of life. J. Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.; Adamson, T.M.; Horne, R.S. Validation of actigraphy for determining sleep and wake in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelemy, I.; Barrey, E.; Aguilar, P.; Uriarte, A.; Le Chevoir, M.; Thibaud, J.L.; Voit, T.; Blot, S.; Hogrel, J.Y. Longitudinal ambulatory measurements of gait abnormality in dystrophin-deficient dogs. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.M.; Elliott, J.A.; Duffy, P.; Blake, C.M.; Ben Attia, S.; Katz, L.M.; Browne, J.A.; Gath, V.; McGivney, B.A.; Hill, E.W.; et al. Circadian regulation of locomotor activity and skeletal muscle gene expression in the horse. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christie, M.A.; McKenna, J.T.; Connolly, N.P.; McCarley, R.W.; Strecker, R.E. 24 h of sleep deprivation in the rat increases sleepiness and decreases vigilance: Introduction of the rat-psychomotor vigilance task. J. Sleep Res. 2008, 17, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ishida, T.; Obara, Y.; Kamei, C. Effects of some antipsychotics and a benzodiazepine hypnotic on the sleep-wake pattern in an animal model of schizophrenia. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 111, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martelli, D.; Luppi, M.; Cerri, M.; Tupone, D.; Perez, E.; Zamboni, G.; Amici, R. Waking and sleeping following water deprivation in the rat. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, S.; Tsutsui, R.; Obara, Y.; Ishida, T.; Kamei, C. Effects of histamine H1-antagonists on sleep-awake state in rats placed on a grid suspended over water or on sawdust. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whimbey, A.E.; Denenberg, V.H. Two independent behavioral dimensions in open-field performance. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1967, 63, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.N.; Cummins, R.A. The Open-Field Test: A critical review. Psychol. Bull. 1976, 83, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, M.A.; Russo, P.V.; Masten, V.L. Multivariate assessment of locomotor behavior: Pharmacological and behavioral analyses. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 25, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanberg, P.R.; Hagenmeyer, S.H.; Henault, M.A. Automated measurement of multivariate locomotor behavior in rodents. Neurobehav. Toxicol. Teratol. 1985, 7, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees, C.V.; Acuff-Smith, K.D.; Minck, D.R.; Butcher, R.E. A method for measuring locomotor behavior in rodents: Contrast-sensitive computer-controlled video tracking activity assessment in rats. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1992, 14, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.S.; Li, Y.C.; Lin, M.T. A modularized infrared light matrix system with high resolution for measuring animal behaviors. Physiol. Behav. 1993, 53, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, R.; Shinomiya, K.; Takeda, Y.; Obara, Y.; Kitamura, Y.; Kamei, C. Hypnotic and sleep quality-enhancing properties of kavain in sleep-disturbed rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 111, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maski, K.P.; Kothare, S.V. Sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral functioning in children. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 89, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoff, J.; Wiebe, S.T.; Gruber, R. Sleep patterns and the risk for ADHD: A review. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2012, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruber, R.; Wiebe, S.; Montecalvo, L.; Brunetti, B.; Amsel, R.; Carrier, J. Impact of sleep restriction on neurobehavioral functioning of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sleep 2011, 34, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shinomiya, K.; Shigemoto, Y.; Okuma, C.; Mio, M.; Kamei, C. Effects of short-acting hypnotics on sleep latency in rats placed on grid suspended over water. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 460, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esaki, S.; Nakayama, M.; Arima, S.; Sato, S. Use of Actigraphy for a Rat Behavioural Sleep Study. Clocks & Sleep 2021, 3, 409-414. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3030028

Esaki S, Nakayama M, Arima S, Sato S. Use of Actigraphy for a Rat Behavioural Sleep Study. Clocks & Sleep. 2021; 3(3):409-414. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsaki, Shinichi, Meiho Nakayama, Sachie Arima, and Shintaro Sato. 2021. "Use of Actigraphy for a Rat Behavioural Sleep Study" Clocks & Sleep 3, no. 3: 409-414. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3030028