1. Introduction

Professional archaeologists have ethical obligations to preserve the archaeological record, to consult with communities affected by archaeological research (often called stakeholders), and to engage the public through outreach [

1,

2,

3,

4]. At times, these principles come into conflict. Local communities do not always benefit from archaeological preservation and outreach. In consideration of the goals of this special issue, we offer a frank reflection on attempts to make our international archaeological project more meaningful to the people living around our research site, Ceibal. This work remains in progress, and although we provide several ideas, we do not have a clear solution at this time.

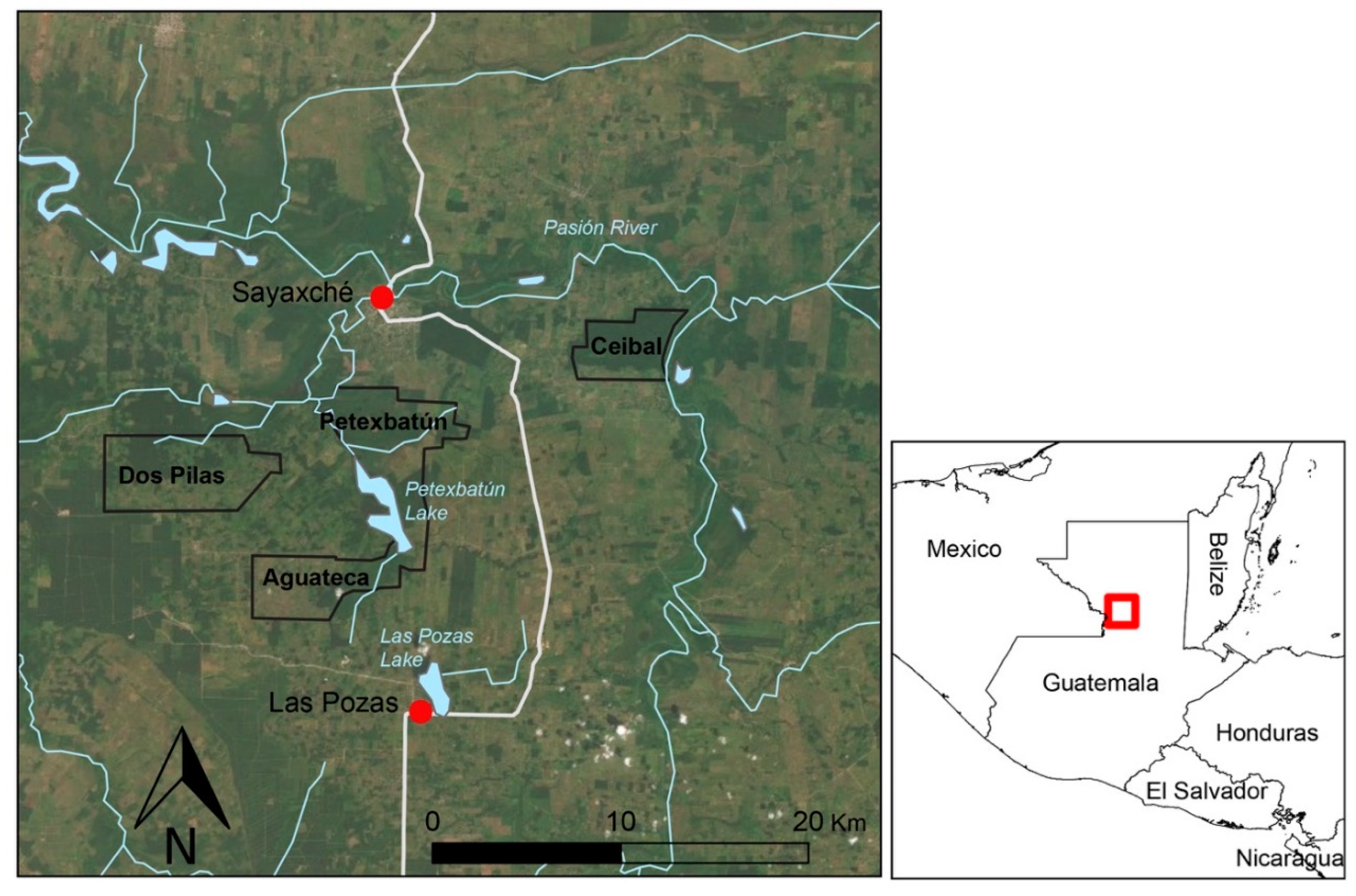

The ancient Maya center of Ceibal (formerly Seibal) is located on the Pasión River in southwestern Petén, Guatemala, near the modern town of Sayaxché (

Figure 1). Ceibal was occupied for approximately two millennia and is known for its Early Middle Preclassic public plaza (c. 950 BC) and Terminal Classic resurgence (c. AD 810-950) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Other Maya sites in the Petexbatún-Pasión region (named for the Petexbatún Lake and Pasión River) include the Classic Maya twin capitals of Aguateca and Dos Pilas, as well as smaller centers like Arroyo de Piedra, Tamarindito, and Punta de Chimino.

After conducting multiple seasons of fieldwork at Aguateca, Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan began the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project at Ceibal in 2005 [

9]. Since the 1990s, Inomata, Triadan, and colleagues have seasonally employed many local people, particularly a group of skilled excavators from the Q’eqchi’ Maya village of Las Pozas (

Figure 1). The size of the team has varied over the years, but the project at Ceibal normally employed around 50 local people (in addition to several Guatemalan archaeologists and students) for a field season of two to three months. The authors were trained by Inomata and Triadan and eventually supervised investigations and operations at Ceibal. MacLellan and Burham completed their dissertation research at Ceibal and helped manage the larger project during the 2013–2017 seasons. Méndez Bauer worked as an archaeologist while also completing a

licenciatura degree in Sociology based on a microsavings project in Las Pozas, described below.

The Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project was not conceived or carried out as a community-based, collaborative archaeology project [

10,

11,

12]. However, the project’s directors and members have made efforts to form mutually beneficial relationships with local communities, especially Las Pozas, while promoting heritage preservation. This is not an easy task, given the many serious problems facing the people of the region. Future research at Ceibal should entail a more community-oriented approach, in order to more effectively and strategically make a positive impact in the region.

2. The Petexbatún-Pasión Region and Its Inhabitants

The Q’eqchi’ (sometimes written Kekchi) people, speakers of the Q’eqchi’ Mayan language, are the largest indigenous group in Petén and southern Belize [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The Q’eqchi’ migrated into these lowlands from Alta Verapaz in multiple waves, beginning in the late 1800s. The migrants left the highlands in search of land to farm, but also to escape first exploitative coffee plantations, then forced labor conscription, and finally the violence of the 1960–1996 Guatemalan civil war [

15] (pp. 58–70). Las Pozas and many other villages around Sayaxché were founded in the context of the civil war. Since the 1960s, the Q’eqchi’ population has more than tripled, with much of the growth occurring in the lowlands [

15] (pp. 79, 108–113). Based on survey data from 1998, Liza Grandia reports a fertility rate of 8.9 children for rural Q’eqchi’ women [

15] (p. 79). According to more recent census data, the Q’eqchi’ population in Guatemala grew from 852,012 in 2002 to 1,370,007 in 2018 [

17,

18]. Meanwhile, the overall population of Petén increased from 366,735 in 2002 to 545,600 in 2018. In 2018, 147,530 inhabitants of Petén (27%) identified as Q’eqchi’. For the municipality of Sayaxché, the population grew from 55,578 in 2002 to 93,414 in 2018. In 2018, 54,313 residents (58%) identified as Q’eqchi’.

The area around Sayaxché differs greatly from the Maya Biosphere Reserve of northern Petén, where Tikal and other well-known Maya archaeological sites are located. Although Ceibal is protected as a small national park, much of the Petexbatún-Pasión region has been deforested since the 1996 peace accord (

Figure 1). The majority of the land has been bought up by palm oil producers and cattle ranchers, leaving little room for subsistence farming. Throughout Central America, deforestation for cattle ranching and other extractive industries has been tied to narcotics trafficking [

19,

20]. McSweeney et al., correlate an intensification of the drug trade with an annual forest loss rate of 10% in the protected parks around Sayaxché [

21] (p. 489).

Many of the region’s cattle ranchers and

palmeras purchased their land from Q’eqchi’ semi-subsistence farmers for relatively small sums of cash, displacing people who assumed they would always be able to migrate further into the frontier but now find themselves “enclosed” on all sides by private property [

15] (pp. 151–157, 164–67). Sometimes companies compelled rural farmers to sell their land by systematically cutting off access to roads and water sources [

22]. The national parks (

Figure 1) established for ecological and archaeological preservation further limit access to land [

23]. The lack of available farmland is a problem for the large and growing population of Q’eqchi’ people in communities like Las Pozas. In the absence of other employment options, many are forced to work for low wages for the palm oil companies. There are not enough jobs, and families that once sustained themselves through farming are facing increased food insecurity. In addition to exploitative labor practices, palm oil has brought environmental damage to the Sayaxché area, including a widely reported 2015 “ecocide” event in which illegal pesticides were dumped into the Pasión River [

24].

The lack of economic opportunity in Petén and insufficient assistance from the Guatemalan state cause both Q’eqchi’ people and

ladinos (Spanish-speaking

mestizo people who do not identify as indigenous) to rely on undocumented, dangerous migrations to the United Sates. Ideally, a person will work in the U.S. for a few years, sending back money to their loved ones, and then return to the community. In practice, the outcome may not be so happy. For example, in 2015, two young relatives of

ladino Ceibal-Petexbatún Project employees were kidnapped and injured by a cartel en route to the United States. The family of these migrants was forced to come up with

$7000 USD to secure their release. It could have been worse. Many people from Central America die trying to cross the U.S. border every year [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Despite the known risks of violence, extortion, and even death, Petén residents with families to support still choose to migrate to the United States.

Due to the absence of available farmland, increasing populations, and few employment opportunities, many of the Petexbatún-Pasión archaeological sites have been “invaded” in order to plant illicit

milpas, or fields of maize (corn) and beans, destroying primary rainforest and disturbing archaeological contexts. Although traditional swidden (shifting, or “slash-and-burn”) agriculture, in which small fields are cleared and then left fallow so that the soil regenerates, may be ecologically sustainable [

29,

30,

31,

32], there is not enough space in the remaining forests around Sayaxché to allow for this practice, given the population size [

15] (p. 109). Instead, large, contiguous areas of the Aguateca and Dos Pilas parks have been completely deforested (

Figure 1). During the Ceibal-Petexbatún Project’s 2015 field season, Q’eqchi’ people from a village near Las Pozas entered the Ceibal National Park and cleared 28 hectares of forest. They argued that as descendants of the ancient Maya, they had a right to this land. In an ensuing confrontation, some used machetes to attack police officers. Several farmers were arrested. In the following days, we heard rumors from our friends in Las Pozas that people from the invaders’ village were planning to come to Ceibal, burn the modern structures, and kidnap the site guards in order to exchange them for the arrested men. These events did not come to pass, although some of the villagers did remove an ancient Maya stone sculpture from the site.

Looting is another destructive activity observed at the archaeological sites of the Petexbatún-Pasión region. The Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH), part of Guatemala’s Ministry of Culture and Sports, has effectively guarded the epicenter of Ceibal. However, other parts of Ceibal and satellite settlements on private lands have been heavily looted. The authors do not know the age of the observed looters’ pits around Ceibal and are unsure to what extent looting continues today. Thanks in part to restrictions on the import of Guatemalan antiquities, looting in Petén has decreased over the past few decades [

33,

34]. In contrast with other countries around the world, in Guatemala, drug traffickers do not participate intensively in the trade of looted artifacts, as the antiquities trade is no longer as profitable as other forms of organized crime in the region [

35,

36]. Nevertheless, local people may continue to dig into ancient Maya structures on a small, non-professional scale, to supplement their low incomes [

34] (p. 428). As archaeologists, we are concerned with the loss of scientific knowledge caused by looting and the commercialization of antiquities. However, like many researchers, we recognize that local people need to make a living, and our preservation efforts should not stand in the way [

37,

38,

39]. By engaging with local communities, we hope to find ways to make the preservation of the region’s cultural and natural resources more economically beneficial than looting and large-scale deforestation.

3. Community Engagement by the Archaeological Project

Throughout the history of the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project, the researchers have endeavored to form mutually beneficial relationships with local communities. Early on, Inomata and Triadan worked with their employees and friends in Las Pozas to plan an ecotourism project to provide income and protect the area’s archaeological sites [

40]. Méndez Bauer oversaw a microsavings project, described below, in collaboration with members of the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) at the University of Arizona [

41]. These projects ultimately did not result in long-term benefits for Las Pozas. A few cultural anthropology graduate students were also recruited to conduct ethnographic research in Las Pozas, but they left due to concerns over safety in Petén as a whole. Following the 2015 field season, MacLellan undertook an outreach project in Las Pozas schools, described below [

42]. Burham and MacLellan plan to continue research at and around Ceibal and hope to strengthen ties and establish new collaborations in Las Pozas and nearby communities.

3.1. Microsavings Project

Microsavings groups are an approach to microfinance fundamentally focused on savings [

43,

44,

45]. These programs address the needs of those who are not served by institutional lenders and traditional rotating credit associations – especially women, who are one of the groups most discriminated against in traditional finance. In a typical microsavings project, 10-20 women voluntarily form a group that democratically elects officers, sets bylaws, meets weekly, and collects savings from each member. At meetings, each woman contributes a sum of money (previously established by the members) to a communal pool. When a woman needs a loan, she requests the desired amount from the group. Once all requests are heard, the group collectively discusses whether enough funds are available and how to prioritize requests if the funds are insufficient. Loans must be repaid with interest at a rate set by the members, which is generally around 10%. The interest collected continually increases the amount of money available to the women, giving each member greater access to money than she could feasibly save on her own. At a predetermined date, the group divides the entire fund equally among members and decides whether, and under what conditions, to start a new cycle. Groups sometimes opt to increase their weekly contributions, accept new members, or change leadership positions at that time.

From 2010 to 2012, Méndez Bauer, under the guidance of Tara Deubel and Mamadou Baro of BARA, oversaw a microsavings project in Las Pozas. This was one of the first microsavings initiatives in Guatemala, and project members and Las Pozas residents participated in a training workshop conducted by Oxfam. The effort was funded by the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project. In March 2010, Méndez Bauer and colleagues conducted community meetings in Las Pozas, a focus group, and a visit to existing microsavings groups in Salamá, Baja Verapaz. Two microsavings groups were formed. One group was made up of nine women – mainly the wives of archaeological project employees. The second group was made up of men – excavators for the archaeological project. Méndez Bauer was assigned to follow the work of both groups during the archaeological field seasons (generally falling within January–April). Outside of the field seasons, the groups were supposed to function with only remote assistance.

Méndez Bauer found that many participants needed more institutional presence to keep working on the savings groups. In 2011, when the archaeological field season resumed, only the group of women had continued to function. This group operated successfully for almost three years. The average loan amount within the group for the duration of the program was $17 USD.

The women started by saving money that their husbands earned, but then raised their own funds. They started a new business making silk-screened T-shirts to sell to tourists at Ceibal. They eventually sold almost 75 T-shirts to increase their savings pool. Wanting more, the women started a store open only on weekends to keep increasing the savings.

For the rest of 2011, Méndez Bauer visited Las Pozas and worked with the microsavings group for 15 days each month. During this period, the group worked through personal differences but in harmony. At the end of the year, the group had saved more than Q 5000 ($630 USD). However, with this money available, problems started. Rejection of loan requests was the principal cause of enmity. In 2012, during the next archaeological field season, Méndez Bauer worked with the microsavings group weekly. The group functioned, but with many infringements of the bylaws, including failure to repay debts. In the final months of 2012, the microsavings group dissolved.

Based on conversations with community members, Méndez Bauer found that the microsavings project did not fulfill the participants’ expectations of making a large amount of money quickly. The women of the microsavings group initially hoped to save Q 10,000, and they were disappointed to accumulate only half that amount. The women compared the microsavings program unfavorably with Bolsas Solidarias and other government assistance programs, through which they received food rations and immediate financial support to keep their children in school. Similarly, in regard to the eco-tourism effort supported by Inomata and Triadan, participants told Méndez Bauer they imagined they would quickly have a large hotel with many guests and became disillusioned when they invested many resources without achieving that goal. In the future, it will be important to set realistic goals for outreach and development projects, to prevent such disappointments.

Other factors may have limited the success of the microsavings initiative. Like the ecotourism project, the microsavings initiative was carried out in collaboration with local people. However, in both cases, the community members who participated were already financially connected to the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project. The perception of these development projects throughout wider Las Pozas is unclear. The long relationship between the research project and the families of its seasonal employees could potentially cause negative reactions, given the resulting differences in access to economic opportunities. In addition, the microsavings framework came entirely from outside Las Pozas. It required training by an international NGO and consistent involvement by Méndez Bauer. The concept was not adopted by other groups throughout Las Pozas. The microsavings model may not suit the community’s interests and needs.

3.2. Classroom Outreach Project

In 2016, MacLellan began an archaeological outreach program for schools in Las Pozas. The main goals of the Las Pozas Archaeological Education Project were (1) to share knowledge from the investigations at Ceibal with a local, descendant community; (2) to encourage the preservation of archaeological sites for their cultural and natural resources; and (3) to start giving a young generation tools they might use in careers related to heritage. MacLellan also sought to dispel common rumors that archaeologists search for gold, buy and sell artifacts, or take excavated materials out of Guatemala. This was a preliminary effort, and an additional goal was to find out what the schools actually wanted from an archaeological project. MacLellan was assisted by Marcos Xe, a resident of Las Pozas, former excavator for the Ceibal-Petexbatún Project, and current teacher. Patricia McAnany shared bilingual Spanish-Q’eqchi’ materials, including coloring books, designed by the Maya Area Cultural Heritage Initiative (MACHI)/InHerit [

46] (pp. 109–118). The Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project donated boxes of school supplies.

MacLellan and Xe visited two private secondary schools where Xe had close professional ties. MacLellan used past experience in public outreach to give accessible and colorful presentations that facilitated interactions with the students. For example, in front of a PowerPoint slide featuring photos of a cacao tree and cacao pods, MacLellan asked the students what they knew about this plant and what it is used for (chocolate), and the children responded enthusiastically. Topics covered included archaeological methods; Ceibal as one of the earliest Maya settlements; plants, animals, and technologies used by the ancient Maya; the Mesoamerican ballgame; Maya numbers, calendars, and writing; Maya kings and queens; and the Classic Maya “collapse” as a political transformation, rather than a mysterious disappearance or disaster.

Although the students and teachers seemed glad to hear about the ancient Maya, archaeology was not the main priority in the schools. After talking about Ceibal in imperfect Spanish, MacLellan was surprised to find herself recruited to teach a full day of English lessons. The English language is considered a valuable skill in Guatemala and is part of the schools’ curricula. Q’eqchi’ students, already bilingual, are eager to learn this third language. The problem in Las Pozas, and probably in many communities, is that the teachers do not speak English. Many of their educational materials are written completely in English, with no Spanish translations. Teaching English was not part of the original plan, but it was a way to respond to the community’s needs and thank the school for welcoming an archaeologist. Foreign language skills would be useful to students in many careers, including archaeological tourism.

Upon hearing about the visits to the two private schools, the council of leaders in Las Pozas decided that the outreach project should include the public schools. MacLellan and Xe were summoned to a meeting. They explained the project and passed around samples of the bilingual coloring books. The members of the council spoke for long stretches in Q’eqchi’ and eventually agreed that the outreach project, including English lessons, should be expanded. MacLellan plans to return to Las Pozas during the next phase of her research at Ceibal, and she hopes to expand the outreach project to additional communities in the area.

4. Discussion and Future Directions

Through community engagement initiatives around Ceibal, we seek to (1) make a positive impact on the lives of local people and (2) encourage the protection of cultural heritage. Several structural problems in the region pose barriers to these goals. They include the displacement of local populations (mainly by palm oil producers and cattle ranchers) and widespread poverty.

Another challenge in the area around Sayaxché is a seeming absence of interest in the ancient past. Both deforestation and looting of the Petexbatún-Pasión archaeological sites might be alleviated by a sense of stewardship among local and descendant communities. Informal conversations with the Q’eqchi’ and

ladino people employed by the archaeological project have given us the impression that local people do not identify strongly with the ancient Maya. Because the Q’eqchi’ are relatively recent migrants to the Maya lowlands, the local archaeological sites are not part of their long-term social memory or traditions. Nevertheless, some Maya groups make pilgrimages to Ceibal to perform rituals, particularly around Semana Santa (Easter week). To reinforce their right to settle in the region, some Q’eqchi’ informants have explained to ethnographers that the Itza Maya are the original inhabitants of Petén and “elder cousins” of the Q’eqchi’ [

15] (p. 80). Since the Itza population is small, they conclude that there is plenty of land to share with their “cousins.” During the Ceibal “invasion” of 2015, representatives of one Q’eqchi’ community did claim ancestral rights to the site in order to access land for agriculture. Ideally, this sense of kinship could lead to the curation of archaeological sites, although the dire conditions in Petén might prevent local people from preserving cultural heritage without economic incentive. At the moment, our desire to protect archaeological sites is at odds with indigenous claims to land and with the economic needs of the population. Such conflicts between local/indigenous land rights movements and archaeological preservation initiatives are not uncommon in the Maya lowlands [

23,

47,

48,

49]. Community land concessions have been successful in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. However, around Sayaxché, the population size and number of stakeholder communities compared to the area of remaining forest make us doubt that model would be effective in the national parks. Hopefully, in cooperation with local people, we can find a way for cultural heritage to benefit the region economically.

In the early stages of the MACHI/InHerit programs, Shoshaunna Parks and colleagues found that some Maya communities did not preserve cultural heritage largely due to a disinterest in the past and an absence of education about archaeology [

34]. The project’s efforts in public outreach, classroom programming, and community-based archaeology have been successful in stimulating cultural preservation in many areas [

46]. As part of the next phase of the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project, we will continue archaeological outreach in Las Pozas and expand to other communities, in order to provide basic information about cultural heritage and promote preservation. We will continue to educate children about archaeology and the ancient Maya through classroom visits and will propose public lectures and question-and-answer sessions for adult audiences. We should also offer informal English lessons, like those requested in Las Pozas.

So far, our archaeological outreach has also been unidirectional. However, we hope to work with interested locals to shift to a bidirectional framework in which local and traditional knowledge would be presented alongside archaeological information. We will take a “co-creative” approach in which archaeologists and community members decide on the outreach program’s goals and manage the resulting projects in dialogue [

50,

51]. The Proyecto de Investigación Arqueológico Regional Ancash, in Andean Peru, found that this flexible, bottom-up approach increased interest in local history and heritage, encouraged the preservation of archaeological materials, and provided additional income in the rural community of Hualcayán [

52]. That collaboration included an annual heritage festival, a women’s textile business, and an oral history project carried out by school children. After the introduction of these programs, the people of Hualcayán prevented gold mining and looting activities that threatened the local archaeological site, arguing that the site belongs to the whole community and is a valuable part of its heritage and way of life. In the Maya community of Tihosuco, Quintana Roo, Mexico, a collaborative heritage project resulted in the Caste War Museum, accompanying digital and printed resources, an oral history project, educational comic books, and an annual exhibition [

53,

54]. Guided by the goals of local people, archaeologist Anne Pyburn has collaborated on multiple successful heritage programs in Belize and Kyrgyzstan [

39]. Anabel Ford and colleagues at El Pilar, Belize, worked with local experts in traditional Maya agriculture to create a model sustainable garden at a local school and associated educational materials [

55,

56,

57]. South of Ceibal, at Candelaria Caves and Salinas de los Nueve Cerros, collaborative work by Brent Woodfill and colleagues has resulted in local infrastructure improvements, as well as community investment in archaeological research [

58,

59]. The products of a co-creative outreach project in the area around Ceibal would obviously depend on the interests and investment of the communities involved.

We plan to reach out to both Q’eqchi’ and

ladino communities, since both are potential stewards of the region’s archaeological sites. It is important to emphasize that the living Maya are descendants of the ancient Maya who built the impressive cities that draw so many tourists and researchers to Petén. However, both indigenous and non-indigenous groups live in and among the archaeological sites of the Petexbatún-Pasión region and are affected by decisions about how these sites are used. Both groups also suffer from poverty, although the Q’eqchi’ endure additional racial discrimination. Surveys conducted in Petén by MACHI/InHerit suggest both

ladinos and Maya people are unfamiliar with the concept of cultural heritage but are interested in learning more about it [

46] (pp. 170–177). These results give us hope that both Q’eqchi’ and non-indigenous groups around Sayaxché may participate in outreach and preservation efforts.

The limited success of our past development and outreach efforts could be due to our lack of a full and nuanced understanding of the communities around Ceibal. Pyburn argues that all archaeological outreach projects should begin with ethnographic research, because initiatives must be aligned with the goals of complex, dynamic communities in order to be successful [

60]. Burham is interested in collaborating with cultural anthropologists on an ethnographic project that explores local conceptions of heritage and how archaeological work shapes or affects the identities of indigenous and

ladino communities residing near archaeological sites. Researchers will gain insights about communities’ expectations of archaeologists and ideas about how our project can help them economically. The goal of this project is to empower local groups to take an active, leading role in heritage-related activities.

Further collaboration with local people and experts like ethnographers, ethnobotanists, ecologists, and indigenous leaders could lead to sustainable farming and gardening initiatives that provide food and income and motivate the protection of forests [

56]. Although Q’eqchi’ communities in Belize plant a diverse set of crops for consumption and sale, Q’eqchi’ farmers in Petén focus heavily on maize and beans. The Q’eqchi’ of Belize also make greater use of wild resources, and they have been able to adapt to today’s economy by, for example, specializing in cacao production. The subsistence strategies seen in Belize are more sustainable, more nutritious, and tied to a stronger sense of stewardship over the environment [

15] (pp. 94–101). In contrast, due to their history of dislocation, plantation labor, and private (versus communal) land ownership, the Q’eqchi’ of lowland Guatemala have lost some traditional agricultural and ecological knowledge, including the culturally and spiritually proper ways to cultivate many plants [

15] (pp. 101–103). In addition, rural farmers in Petén know that they can sell maize and beans, while the market for other crops is less certain. They often lack access to funds or credit needed to invest in risky agricultural innovations [

61]. We are interested in identifying and partnering with groups who could bring traditional knowledge of sustainable subsistence practices to communities around Ceibal, and who could make those practices economically feasible. This would be a highly interdisciplinary project, requiring ecological and cultural expertise [

62].

While sustainable agriculture has clear benefits, the question of how archaeological research and preservation could materially help the people of the Petexbatún-Pasión region is a difficult one. This topic requires more collaboration with communities and with experts from outside archaeology. To the best of our knowledge, few archaeologists have measured the economic benefits of the development and conservation projects they initiate or support in local communities. One example is the Sustainable Preservation Initiative (SPI), directed by Lawrence Coben, which reports quantitative and qualitative results of its “community-based sustainable economic development” programs that center on tourism and the sale of crafts [

37]. SPI has funded ventures around the world, including several in Peru and one associated with the Maya site of Kaminaljuyu, in Guatemala City. The results from San Jose de Moro, Peru, include positive economic and archaeological preservation outcomes [

37]. Looting in San Jose de Moro has decreased, and local officials have prevented development and agricultural projects that threatened the site. This result is similar to the increased interest in preservation observed in Hualcayán. Coben credits the success of SPI to the bottom-up, community-controlled nature of funded projects.

With the example of SPI in mind, we would like to build on Inomata’s and Triadan’s efforts to bring economic aid to communities around Ceibal through sustainable tourism. The commodification of heritage through tourism often marginalizes local and indigenous people [

63,

64], but when local communities are in charge, tourism can be empowering [

65]. As in the case of San Jose de Moro, tourism and related businesses may help protect the region’s cultural and natural resources, in addition to bringing much needed income to local communities. The Guatemalan government is currently promoting sustainable tourism, particularly in Petén, or “el Mundo Maya” [

66]. The Guatemalan Tourism Institute considers Ceibal, Aguateca, and Dos Pilas key destinations for archaeology, hiking, birdwatching, and “adventure.” These three sites already draw international tour groups, but visitors do not seem to significantly benefit Las Pozas and the other nearby communities. We would like to help local people profit from this industry, but any efforts in expanding tourism would need to be generated and managed by the communities, possibly in consultation with business or development professionals who could provide expert advice and set realistic goals. If local people are interested in pursuing tourism opportunities, we can imagine assisting them with community museums and archaeological site tours, as well as promoting related businesses like restaurants, eco-hotels and campsites, nature tours, craft markets, and Q’eqchi’ language schools. We note that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted risks of reliance on tourism [

67], and it is unclear how travel will be affected by the novel coronavirus in the long term.

None of these future engagement initiatives – expanding archaeological outreach, conducting ethnographic fieldwork, promoting sustainable agriculture and tourism – can begin without first talking to the communities. In past efforts, we have relied heavily on our seasonal employees as connections to the towns. While these trusted friends are helpful, they make up a small fraction of the population and are likely biased in favor of our work, since they already benefit economically from the archaeological project. During the next phase of the project, we plan to meet with leaders of multiple Q’eqchi’ and ladino communities, like the Las Pozas council MacLellan spoke with in 2016, in order to explain our project’s objectives and ask if they see potential benefits for local people. If possible, we will also hold public meetings to gain a broader understanding of people’s needs and expectations. Our project will need the cooperation of teachers, government officials, and other experts to create activities that will improve economic conditions and protect cultural and natural resources in the Petexbatún-Pasión region. In the end, what we accomplish together may look very different from the ideas put forward here.