Carbon Trading Price Forecasting Based on Multidimensional News Text and Decomposition–Ensemble Model: The Case Study of China’s Pilot Regions

Highlights

- Leveraging multiple NLP techniques to extract textual features and combining them with financial variables signif-icantly boosts carbon price forecasting accuracy.

- Combining ICEEMDAN with heterogeneous machine-learning models enables each model to capture different frequency components, significantly enhancing overall predictive performance.

- Augmenting financial data with diverse text-analysis methods enhances forecasting accuracy, demonstrating the superiority of multi-source information over financial data alone.

- Integrating ICEEMDAN decomposition with heterogeneous ML models yields a powerful forecasting strategy, harnessing the distinct advantages of each model for different frequency components.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- This study proposes a sentiment lexicon specifically tailored to carbon trading news texts. The lexicon is developed by expanding an existing Chinese financial sentiment dictionary using the Word2Vec algorithm to identify sentiment terms closely related to the carbon market. The resulting domain-specific lexicon enables more accurate extraction of sentiment features from unstructured carbon-related textual data.

- (2)

- This study uses multiple text analysis methods, including sentiment analysis, LDA, and CNN, to extract various textual features from news reports. Instead of constructing a single textual indicator, the study incorporates multi-dimensional textual features into the carbon price forecasting framework.

- (3)

- This study applies the ICEEMDAN decomposition method to both textual and financial feature sequences to extract detailed fluctuation patterns and long-term trends. These components reflect the influence of complex factors, such as market volatility and policy evolution, on carbon prices. This approach enables a more fine-grained carbon price forecasting process.

- (4)

- This study integrates the ICEEMDAN method with several advanced machine-learning models to construct an ensemble forecasting framework. Within this framework, the distinct strengths of individual models are strategically leveraged to match the specific characteristics of different frequency components. Empirical results demonstrate that the proposed approach enhances forecasting accuracy and consistently achieves superior performance in both model comparison and robustness evaluation.

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

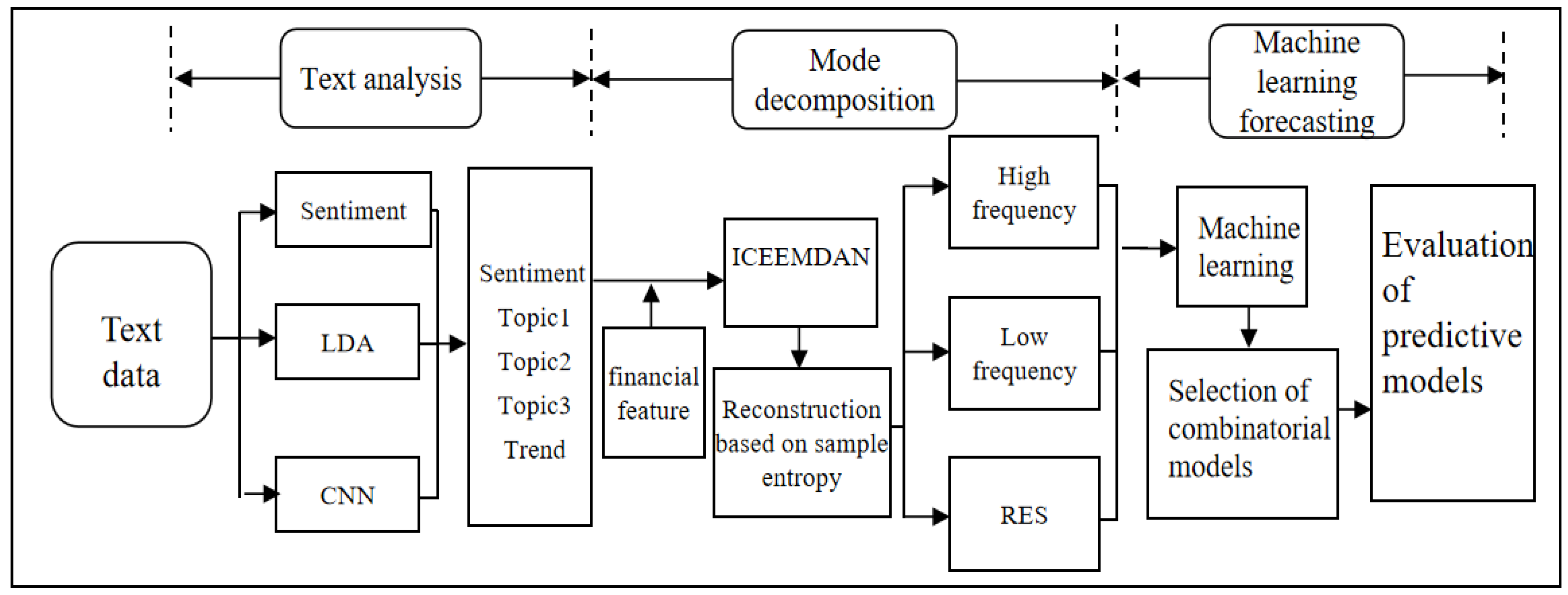

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

- (1)

- Domestic Stock Market

- (2)

- International Exchange Market

- (3)

- Energy Commodity Market

- (4)

- International Carbon Market

3.3. Online News Text Mining

3.3.1. Expansion of the Sentiment Lexicon Using Word2vec

3.3.2. Sentiment Analysis

3.3.3. LDA Model

3.3.4. CNN Model

3.4. Identification of Nonlinear Features

3.5. Decomposition and Reconstruction Method

3.5.1. Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN)

3.5.2. Reconstruction Based on Sample Entropy (SE)

3.6. Carbon Price Prediction Model

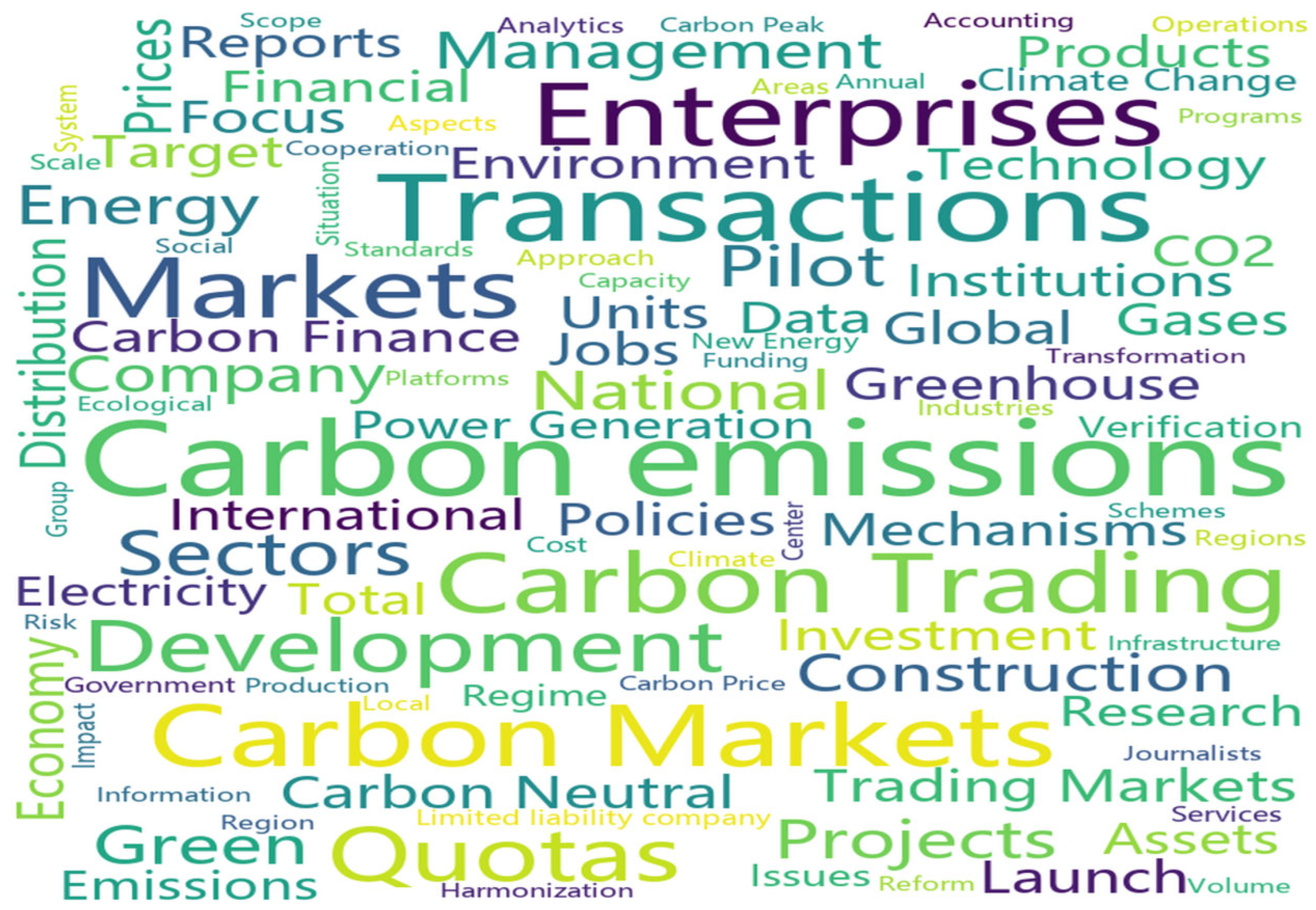

4. Text Analysis of Online News

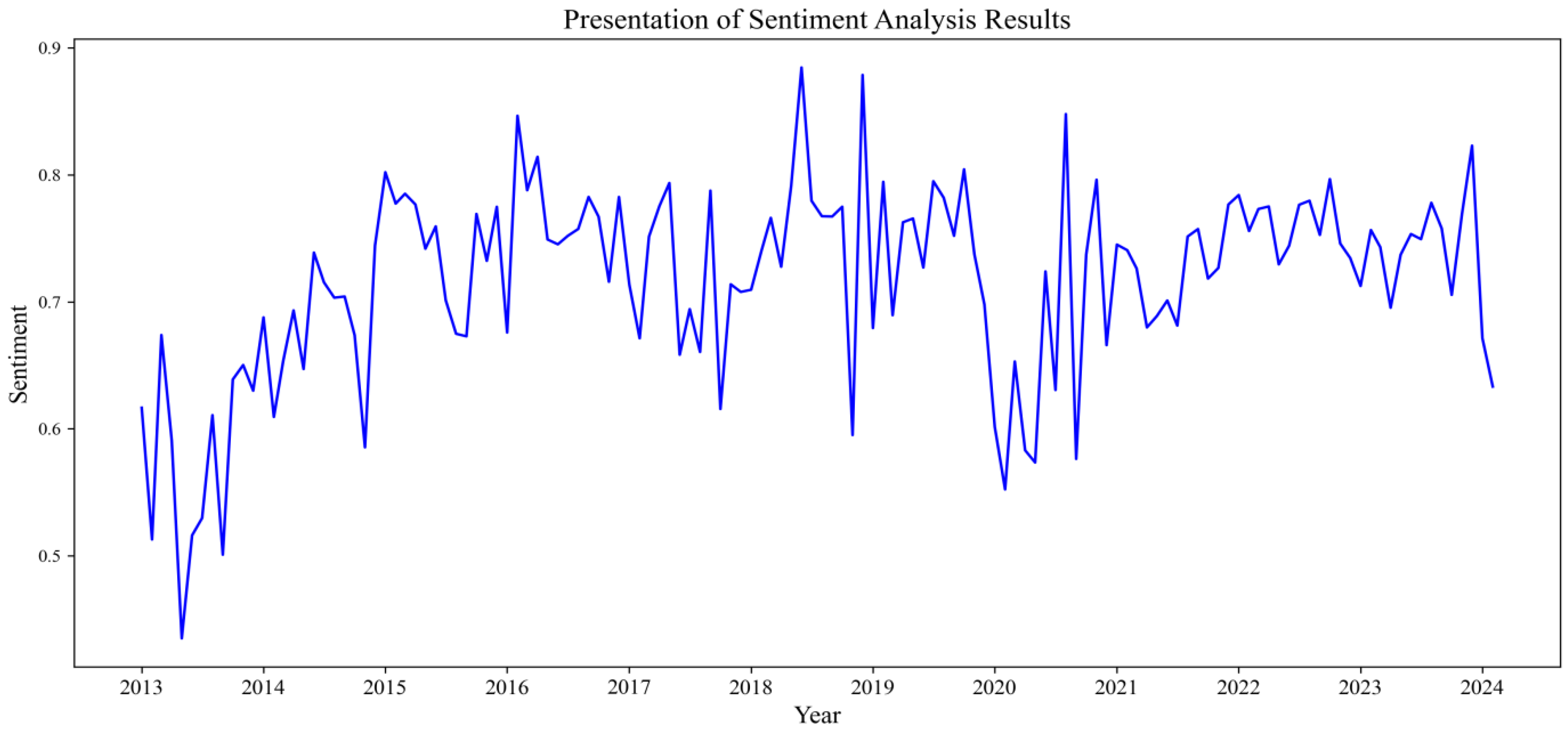

4.1. Sentiment Lexicon Expansion and Sentiment Analysis

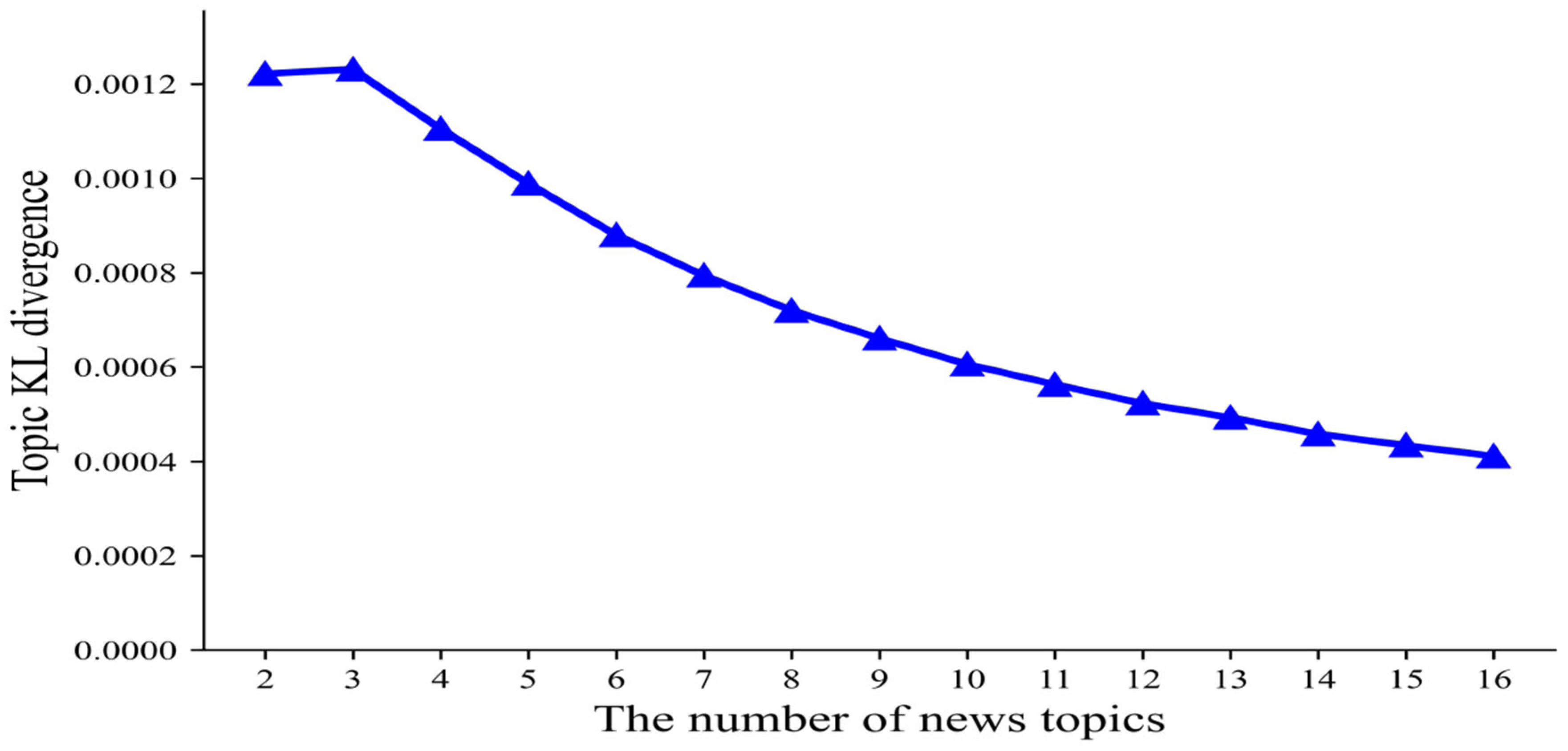

4.2. LDA Topic Model

4.3. CNN Text Classification

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Identification of Nonlinear Characteristics of Feature Variables

5.3. Decomposition and Reconstruction of Carbon Prices and Feature Variable Sequences

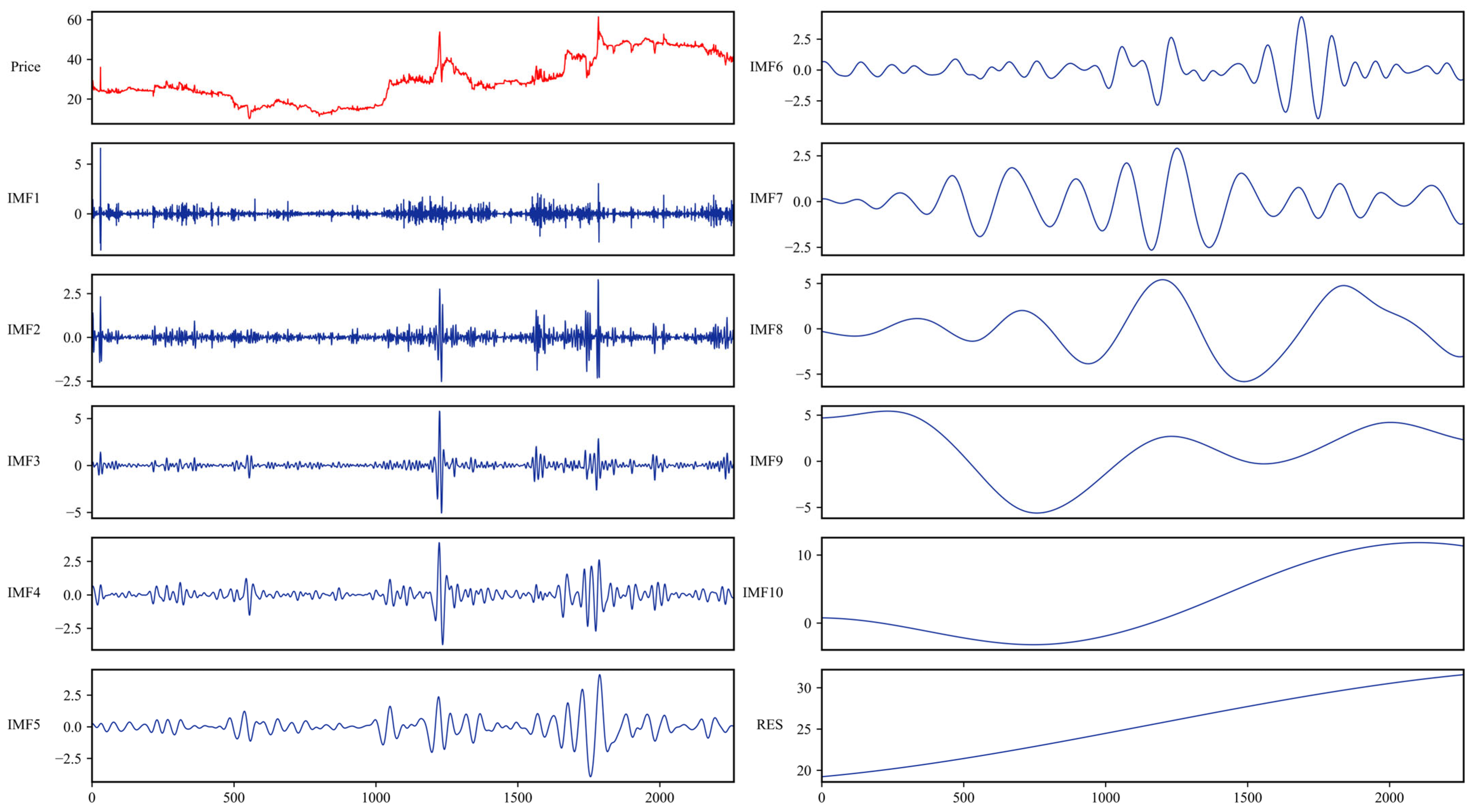

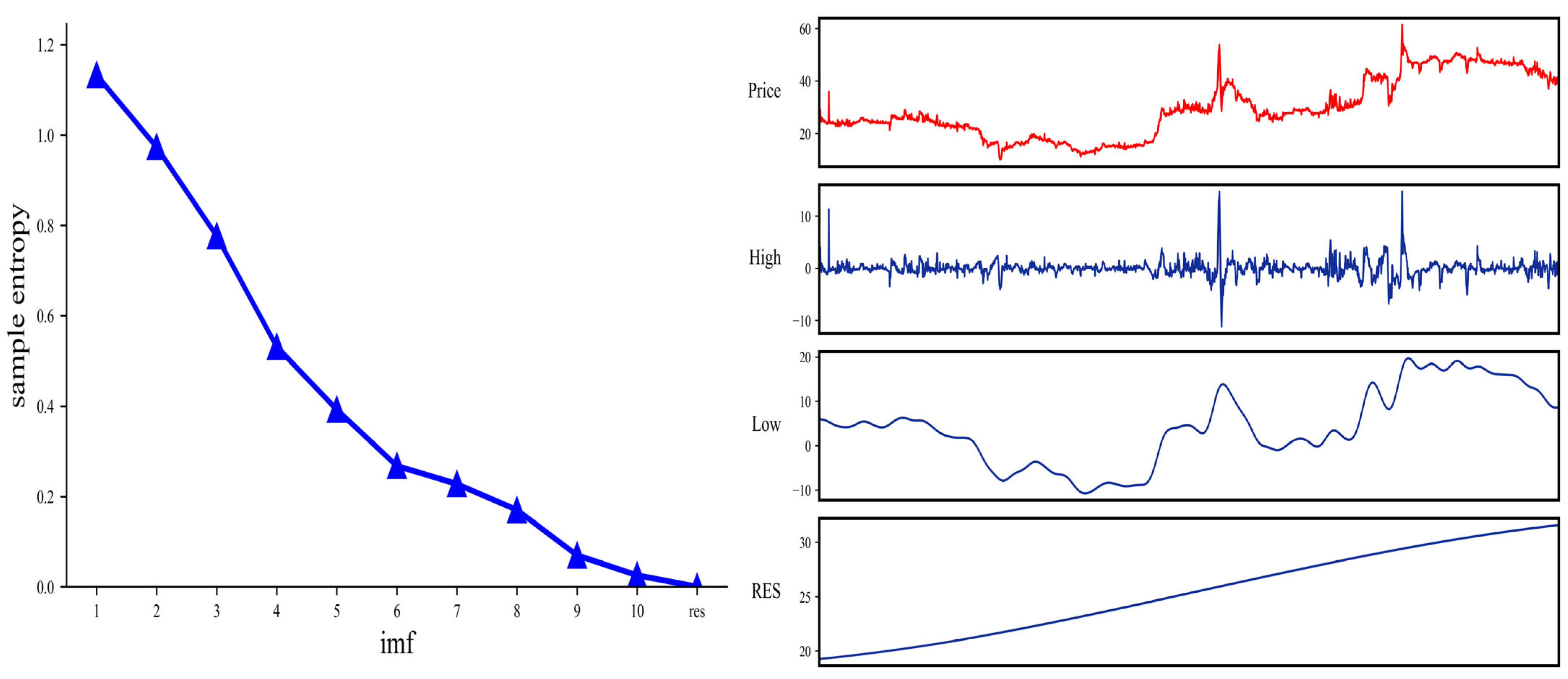

5.3.1. ICEEMDAN Decomposition of the Historical Carbon Price Series

5.3.2. Sequence Recombination Based on Sample Entropy (SE)

5.4. Evaluation of Carbon Price Forecasting Results

5.4.1. Impact of ICEEMDAN Decomposition on Machine Learning Model Performance

5.4.2. Pesaran–Timmermann (PT) Test

5.4.3. Impact of Textual Features on Machine Learning Model Performance

5.5. Diebold-Mariano (DM) Test

5.6. Robustness Checks

5.6.1. Rolling-Window Robustness Test

5.6.2. Robustness Test Across Different Pilot Regions

5.6.3. Robustness Test with Different Sample Splitting Ratios

5.6.4. Robustness Test Across Different Time Steps

5.7. Comparison with Other Commonly Used Models

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

6.2. Policy Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Type | Introduction | Main Advantages and Disadvantages |

| BiGRU | Neural network | The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) designed to mitigate the vanishing and exploding gradient problems that frequently arise in traditional RNNs. Building on this architecture, the Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) further enhances modeling capacity by processing input sequences in both forward and backward directions, thereby capturing more comprehensive contextual information. Through supervised training, BiGRU effectively learns the mapping between input and output sequences, and it has demonstrated strong performance in regression settings, making it particularly suitable for time series forecasting and economic indicator analysis. | Advantages: Capable of capturing long-term dependencies and complex temporal patterns, making it well-suited to sequence modeling tasks. Disadvantages: Involves relatively longer training and inference times and requires greater computational resources compared with simpler models. |

| XGBoost | Decision tree | XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is an efficient implementation of the gradient boosting framework that improves model performance iteratively by constructing an ensemble of decision trees. It incorporates features such as parallel processing, regularization, and tree pruning, which substantially enhance both computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. XGBoost has been widely applied to classification, regression, and ranking problems and is particularly effective when dealing with structured (tabular) data. | Advantages: 1. Delivers high predictive performance with relatively low reliance on manual feature engineering. 2. Effectively handles large-scale datasets and complex nonlinear relationships, while offering built-in mechanisms for regularization and missing-value handling. Disadvantages: 1. Requires careful hyperparameter tuning to achieve optimal performance and to mitigate the risk of overfitting. 2. Training can become computationally intensive for very large models, and the resulting ensembles are relatively less interpretable and may be less suitable than simpler linear models for extremely high-dimensional sparse data. |

| BiLSTM | Neural network | The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network is a widely used variant of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) designed to address the long-term dependency problem inherent in traditional RNNs. It achieves this by introducing a set of gating mechanisms—namely, the forget gate, input gate, and output gate—that control the flow of information through the network. Building on this architecture, the Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network processes input sequences in both forward and backward directions, enabling a more comprehensive capture of contextual information within the sequence. Owing to its ability to incorporate both past and future context, BiLSTM is particularly well-suited for modeling and forecasting complex time series, thereby enhancing model accuracy and robustness. | Advantages: Capable of capturing both long-term and short-term dependencies, making it well-suited for sequence labeling, time series modeling, and forecasting tasks. Disadvantages: Requires relatively long training time and substantial computational resources, and performance may degrade in very deep architectures if hyperparameters are not carefully tuned. |

| RF | Decision tree | Random Forest is an ensemble learning algorithm based on decision trees. It constructs multiple decision trees on bootstrap samples of the data and aggregates their predictions (e.g., by averaging for regression or majority voting for classification) to enhance robustness and generalization performance. By randomly selecting both samples and feature subsets when growing each tree, Random Forest effectively reduces model variance and mitigates overfitting. It has been widely applied to classification, regression, and feature-importance evaluation tasks. | Advantages: 1. Less prone to overfitting than a single decision tree, with strong robustness to outliers and missing data. 2. Capable of handling high-dimensional feature spaces and providing measures of variable importance. Disadvantages: 1. The ensemble structure reduces interpretability compared with simpler models, making it difficult to trace individual decision paths. 2. Training and prediction can be computationally intensive for very large datasets or forests with many deep trees. |

| SVR | Support vector machine | Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a variant of Support Vector Machines (SVM) tailored for regression tasks. It employs an ε-insensitive loss function, which allows prediction errors within a specified margin of tolerance, thereby controlling model complexity and improving generalization. By leveraging kernel functions, SVR can effectively model high-dimensional and nonlinear relationships, making it well-suited for applications such as time series forecasting and economic data analysis. | Advantages: Effective in high-dimensional feature spaces and capable of capturing complex nonlinear relationships. Disadvantages: Highly sensitive to hyperparameter selection, with model performance critically dependent on the choice of kernel function and parameter tuning; computational costs can also increase substantially for large datasets. |

| MLP | Neural network | The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is one of the most widely used architectures in artificial neural networks. In its basic form, it consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, with neurons fully connected between adjacent layers. The input layer encodes the observed information into input vectors, the hidden layers apply nonlinear transformations through activation functions, and the output layer produces the final predictive response. Parameters are typically learned via backpropagation and gradient-based optimization. | Advantages: Capable of learning complex nonlinear relationships and adaptable to a wide range of data types and predictive tasks. Disadvantages: Often requires substantial training time, large volumes of data, and careful hyperparameter tuning (e.g., number of layers, neurons, learning rate) to achieve optimal performance and avoid overfitting. |

| Ridge | Linear model | Ridge regression is a regularized form of linear regression that adds an L2 penalty term (the sum of squared coefficients) to the loss function to mitigate overfitting. It is particularly suitable for regression settings with multicollinearity, as the penalty shrinks coefficient estimates toward zero, stabilizes parameter estimation, reduces variance, and enhances generalization performance. | Advantages: Provides stable estimates in the presence of multicollinearity and effectively reduces overfitting. Disadvantages: Relies on linearity assumptions and therefore has limited ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships in the data. |

| Lasso | Linear model | Lasso regression is a regularized variant of linear regression that introduces an L1 penalty term (the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients) into the loss function. This penalty not only helps prevent overfitting but also performs automatic feature selection by shrinking some coefficients exactly to zero, thereby simplifying the model structure and improving interpretability. | Advantages: Simultaneously performs regularization and feature selection by eliminating irrelevant or weakly relevant predictors, which can enhance model interpretability and reduce overfitting. Disadvantages: Relies on linearity assumptions and is therefore limited in its ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships; performance may also become unstable when predictors are highly correlated. |

References

- Li, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Wu, Q. Forecasting carbon prices based on real-time decomposition and causal temporal con-volutional networks. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Salem, S. Explosive behaviors in Chinese carbon markets: Are there price bubbles in eight pilots? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, Z. Carbon price forecasting with optimization prediction method based on unstructured combination. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 725, 138350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gong, X.; Liu, X. Carbon futures return forecasting: A novel method based on decomposition-ensemble strategy and Markov process. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 163, 111869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-T.; Miao, J.; Qu, S.; Chen, X.-H. A multi-factor integrated model for carbon price forecasting: Market interaction promoting carbon emission reduction. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 796, 149110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Hao, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, X. Carbon price prediction considering climate change: A text-based framework. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Okullo, S.J. Drivers and pass-through of the EU ETS price: Evidence from the power sector. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Meng, L.; Tang, G. Media text sentiment and stock return prediction. J. Econ. (Q.) 2021, 21, 1323–1344. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.; Cheng, S.; Tan, X.; Feng, S.; Zhou, Q. Predicting China’s carbon price based on a multi-scale integrated model. Appl. Energy 2022, 324, 119784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S. Forecasting the carbon price of China’s national carbon market: A novel dynamic interval-valued framework. Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shang, W.; Wang, S. Text-based crude oil price forecasting: A deep learning approach. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 35, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L. Carbon price forecasting with variational mode decomposition and optimal combined model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 519, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Guan, K.; Chen, Q. The role of textual analysis in oil futures price forecasting based on machine learning approach. J. Futures Mark. 2022, 42, 1987–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C. Carbon price forecasting based on CEEMDAN and LSTM. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, M.; Guan, K.; Sun, C. Climate change attention and carbon futures return prediction. J. Futures Mark. 2023, 43, 1261–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xia, Z.; Cheng, M.; Tan, X. Carbon price prediction based on multiple decomposition and XGBoost algorithm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 89165–89179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X. A multiscale and multivariable differentiated learning for carbon price forecasting. Energy Econ. 2024, 131, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Sun, W.; Wu, C. MLP-Carbon: A new paradigm integrating multi-frequency and multi-scale techniques for accurate carbon price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Che, J.; Li, S.; Hu, K.; Xu, Y. Incorporating key features from structured and unstructured data for enhanced carbon trading price forecasting with interpretability analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wei, Y. Carbon price forecasting with a novel hybrid ARIMA and least squares support vector machines methodology. Omega 2013, 41, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.J.; Cho, H. Forecasting carbon futures volatility using GARCH models with energy volatilities. Energy Econ. 2013, 40, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Shao, X. A novel interval decomposition ensemble model for interval carbon price forecasting. Energy 2022, 243, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Kuo, Y.-T. A forecasting system of carbon price in the carbon trading markets using artificial neural network. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2013, 4, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Huang, C. A novel carbon price prediction model combines the secondary decomposition algorithm and the long short-term memory network. Energy 2020, 207, 118294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bu, H.; Li, J.; Wu, J. The role of text-extracted investor sentiment in Chinese stock price prediction with the enhancement of deep learning. Int. J. Forecast. 2020, 36, 1541–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, C. The research on setting a unified interval of carbon price benchmark in the national carbon trading market of China. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tan, X.; He, G.; Liu, Y. Disentangling the drivers of carbon prices in China’s ETS pilots—An EEMD approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Hao, Y.; Tan, Z. A hybrid model using signal processing technology, econometric models and neural network for carbon spot price forecasting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.E.; Colominas, M.A.; Schlotthauer, G.; Flandrin, P. A complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 22–27 May 2011; pp. 4144–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colominas, M.A.; Schlotthauer, G.; Torres, M.E. Improved complete ensemble EMD: A suitable tool for biomedical signal processing. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2014, 14, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Lai, K. Crude oil price forecasting with TEI@I methodology. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2005, 18, 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, F.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L.; Yin, H. What drive carbon price dynamics in China? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 79, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 42, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, J.H.; Mansanet-Bataller, M. Causalities between CO2, electricity, and other energy variables during phase I and phase II of the EU ETS. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3329–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, W.; Shi, S.; Zhang, J. Carbon price prediction research based on CEEMDAN-VMD secondary decom-position and BiLSTM. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 8921–8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.-P.; Wang, X.-Y. Dependence changes between the carbon price and its fundamentals: A quantile regression approach. Appl. Energy 2017, 190, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L. A hybrid VMD–BiGRU model for rubber futures time series forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 84, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, S.; Tian, L. Chaotic characteristic identification for carbon price and an multi-layer perceptron network prediction model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zeng, Y.-R. Forecasting the US oil markets based on social media information during the COVID-19 pandemic. Energy 2021, 226, 120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, C. The overall and time-varying efficiency test for the carbon market in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Sun, Y.; Hong, Y.; Wang, S. Forecasting interval carbon price through a multi-scale interval-valued decomposition ensemble approach. Energy Econ. 2024, 139, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Sirichand, K.; Vivian, A.; Wang, X. How connected is the carbon market to energy and financial markets? A systematic analysis of spillovers and dynamics. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rodríguez, R. What happens to the relationship between EU allowances prices and stock market indices in Europe? Energy Econ. 2019, 81, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazifi, F. Modelling the price spread between EUA and CER carbon prices. Energy Policy 2013, 56, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2013, 26, 3111–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Ji, R.; Zhang, W. Tone, sentiment, and market impact: Based on a financial sentiment lexicon. J. Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, 26–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Ma, J.; Jing, K. ESG perspectives and stock market pricing: Evidence from AI language models and news texts. Contemp. Econ. Sci. 2023, 45, 29–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Jia, H.; Zhao, G.; Fu, H. Credit risk early warning for listed companies based on textual information disclosure: Empirical evidence from the MD&A sections of Chinese annual reports. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 31, 18–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Ruan, P.; Liu, X.; Shan, X. A study on user satisfaction evaluation based on online reviews. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 179–189. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Convolutional Neural Network for Sentence Classification. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Broock, W.A.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Dechert, W.D.; LeBaron, B. A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Econom. Rev. 1996, 15, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.S.; Moorman, J.R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H2039–H2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F. A hybrid forecasting system with complexity identification and improved optimization for short-term wind speed prediction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, B. A rationale-augmented NLP framework to identify unilateral contractual change risk for construction projects. Comput. Ind. 2023, 149, 103940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, W.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S. What can be learned from the historical trend of crude oil prices? An ensemble approach for crude oil price forecasting. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Timmermann, A. A simple nonparametric test of predictive performance. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1992, 10, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.; Leybourne, S.; Newbold, P. Testing the equality of prediction mean squared errors. Int. J. Forecast. 1997, 13, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, N.R. Money and output viewed through a rolling window. J. Monet. Econ. 1998, 41, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, M.A. Subsample instability and asymmetries in money-income causality. J. Econom. 1994, 64, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Decomposition Methods | Machine Learning Methods | Text Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li (2019) [11] | \ | Random forest, SVR | CNN, LDA, sentiment analysis |

| Zhu (2019) [12] | VMD | BiGRU | \ |

| Gong (2022) [13] | \ | LightGBM | CNN, LDA, sentiment analysis |

| Zhou (2022) [14] | CEEMDAN | LSTM | \ |

| Gong (2023) [15] | \ | Xgboost, LightGBM | LDA |

| Xu (2023) [16] | CEEMDAN | XGboost | \ |

| Chen and Zhao (2024) [17] | VMD | LSSVM, PSOALS | \ |

| Tian (2025) [18] | VMD | MLP | \ |

| Jiang (2025) [19] | CEEMDAN | SVR | Baidu Index |

| Ours | ICEEMDAN | Ensemble Model (BiGRU, BiLSTM, XGboost) | CNN, LDA, Sentiment analysis |

| Seed Word | Expanded Word | Seed Word | Expanded Word |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power saving | Electricity conservation | Recycling | Carbon cycle |

| Power saving | Water conservation | Recycling | Positive cycle |

| Energy saving | Emission reduction | Carbon neutrality | Carbon peaking |

| Energy saving | Energy consumption reduction | Carbon neutrality | Dual-carbon |

| Energy saving | Carbon reduction | Carbon neutrality | Dual-carbon target |

| Energy saving | Low carbon | High pollution | High energy consumption |

| Governance | Environmental governance | Renewable | Inexhaustible |

| Governance | Comprehensive management | Renewable | Never-depleting |

| Governance | Prevention and control | Renewable | Renewability |

| Restoration | Re-greening | Recycling | Carbon cycle |

| Restoration | Land reclamation | Recycling | Positive cycle |

| Restoration | Enclosure and conservation | Recycling | Circularity |

| Sentence | Sentiment Index |

|---|---|

| As carbon emission quota constraints become increasingly stringent, firms reduce compliance costs and enhance long-term competitiveness by optimizing their energy structure and improving energy efficiency within the carbon market framework. | 0.4286 |

| The continued rise in carbon prices compels high-emission industries to accelerate technological innovation, making decarbonization pathways more explicit under the joint influence of policy pressure and market incentives. | 0.7701 |

| As the national carbon market steadily expands, enterprises increasingly pursue a balance between risk control and return enhancement by developing systematic carbon-asset management mechanisms. | 0.6 |

| A growing share of renewable energy not only enables firms to reduce emissions but also creates greater trading flexibility and profit opportunities within the carbon market. | 0.7059 |

| Integrating pollution control with carbon-emission management helps firms achieve higher creditworthiness and stronger regulatory compliance in the carbon market. | 0.4595 |

| High-pollution industries can obtain more trading opportunities by implementing carbon-reduction measures and adopting low-carbon technological upgrades. | 0.6970 |

| The price signals generated by the carbon market help firms identify potential risks associated with high-carbon assets, thereby facilitating more prudent and forward-looking capital allocation. | 0.5455 |

| As carbon emission constraints become increasingly embedded in industry entry standards, firms proactively optimize their production processes to meet stricter low-carbon requirements in the future. | 0.5745 |

| Dominant_Topic | Top 10 Keywords | Documents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic1 | company project carbon finance finance asset green investment limited company business product | 15163 | 27.85010% |

| Topic2 | industry energy global carbon neutrality green technology policy analysis economy target | 15081 | 27.6995% |

| Topic3 | allowance pilot country construction trading market management launch greenhouse gas mechanism work | 24201 | 44.4504% |

| Type | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down | 0.5963 | 0.5395 | 0.5665 | 4827 |

| Up | 0.5966 | 0.6210 | 0.6226 | 5051 |

| Macro avg. | 0.5965 | 0.5952 | 0.5945 | 9878 |

| Weighted avg. | 0.5965 | 0.5965 | 0.5952 | 9878 |

| Loss | 0.65 | Accuracy | 59.65% |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Jarque–Bera | ADF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRICE | 29.5055 | 11.3366 | 0.4138 | −0.9772 | 154.3191 *** (0.0000) | −2.2895 (0.4588) |

| WTI | 63.6049 | 19.8563 | 0.4796 | 0.1232 | 88.3421 *** (0.0000) | −3.0589 (0.1300) |

| COAL | 103.8717 | 75.1652 | 2.3064 | 4.8678 | 4247.7710 *** (0.0000) | −2.1782 (0.5029) |

| GAS | 33.7225 | 35.4383 | 3.2458 | 12.3637 | 18,416.0400 *** (0.0000) | −2.6872 (0.2874) |

| USD | 6.6637 | 0.3175 | 0.1114 | −1.0157 | 101.5824 *** (0.0000) | −2.0367 (0.5628) |

| EUA | 32.1257 | 30.6710 | 0.8560 | −0.8502 | 344.4157 *** (0.0000) | −2.0702 (0.5486) |

| HS300 | 3822.2380 | 725.9290 | 0.0443 | 0.0711 | 1.2548 (0.5340) | −2.0267 (0.5670) |

| SENTI | 0.7358 | 0.1725 | −1.5170 | 4.4727 | 2759.7940 *** (0.0000) | −10.2491 *** (0.0100) |

| TOPIC1 | 0.2348 | 0.1705 | 0.8534 | 0.8703 | 346.8600 *** (0.0000) | −7.5348 *** (0.0100) |

| TOPIC2 | 0.2984 | 0.1784 | 0.6536 | 0.6601 | 202.7678 *** (0.0000) | −10.2803 *** (0.0100) |

| TOPIC3 | 0.4668 | 0.2157 | 0.3369 | −0.5435 | 70.4797 *** (0.0000) | −9.7355 *** (0.0100) |

| TREND | 0.5609 | 0.2749 | −0.2161 | −0.5970 | 50.9756 *** (0.0000) | −11.5721 *** (0.0100) |

| Dimension | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ||||||

| WTI | 0.0541 *** (0.0000) | 0.0969 *** (0.0000) | 0.1238 *** (0.0000) | 0.1369 *** (0.0000) | 0.1419 *** (0.0000) | |

| GAS | 0.0544 *** (0.0000) | 0.0975 *** (0.0000) | 0.1249 *** (0.0000) | 0.1384 *** (0.0000) | 0.1433 *** (0.0000) | |

| COAL | 0.0548 *** (0.0000) | 0.0978 *** (0.0000) | 0.1249 *** (0.0000) | 0.1383 *** (0.0000) | 0.1432 *** (0.0000) | |

| USD | 0.0540 *** (0.0000) | 0.0974 *** (0.0000) | 0.1245 *** (0.0000) | 0.1380 *** (0.0000) | 0.1431 *** (0.0000) | |

| EUR | 0.0540 *** (0.0000) | 0.0971 *** (0.0000) | 0.1242 *** (0.0000) | 0.1374 *** (0.0000) | 0.1422 *** (0.0000) | |

| EUA | 0.0532 *** (0.0000) | 0.0949 *** (0.0000) | 0.1204 *** (0.0000) | 0.1336 *** (0.0000) | 0.1386 *** (0.0000) | |

| HS300 | 0.0537 *** (0.0000) | 0.0963 *** (0.0000) | 0.1228 *** (0.0000) | 0.1363 *** (0.0000) | 0.1414 *** (0.0000) | |

| SENTI | 0.0537 *** (0.0000) | 0.0964 *** (0.0000) | 0.1234 *** (0.0000) | 0.1368 *** (0.0000) | 0.1418 *** (0.0000) | |

| TOPIC1 | 0.0550 *** (0.0000) | 0.0988 *** (0.0000) | 0.1262 *** (0.0000) | 0.1397 *** (0.0000) | 0.1448 *** (0.0000) | |

| TOPIC2 | 0.0536 *** (0.0000) | 0.0964 *** (0.0000) | 0.1230 *** (0.0000) | 0.1361 *** (0.0000) | 0.1410 *** (0.0000) | |

| TOPIC3 | 0.0533 *** (0.0000) | 0.0959 *** (0.0000) | 0.1223 *** (0.0000) | 0.1352 *** (0.0000) | 0.1400 *** (0.0000) | |

| TREND | 0.0536 *** (0.0000) | 0.0965 *** (0.0000) | 0.1235 *** (0.0000) | 0.1369 *** (0.0000) | 0.1419 *** (0.0000) | |

| Frequency | Model | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-frequency | BiGRU | 0.0056 | 0.0074 | 1.3231 | 0.9699 |

| XGBoost | 0.0070 | 0.0119 | 1.6562 | 0.9217 | |

| RF | 0.0134 | 0.0175 | 3.3457 | 0.8309 | |

| MLP | 0.0095 | 0.0101 | 2.2648 | 0.9433 | |

| BiLSTM | 0.0109 | 0.0125 | 2.5475 | 0.9139 | |

| Low-frequency | XGBoost | 0.0133 | 0.0162 | 1.5168 | 0.9699 |

| RF | 0.0332 | 0.0395 | 3.8003 | 0.8207 | |

| MLP | 0.0284 | 0.0314 | 3.3602 | 0.8873 | |

| BiLSTM | 0.0245 | 0.0273 | 2.9439 | 0.9149 | |

| BiGRU | 0.0196 | 0.0258 | 2.2708 | 0.9235 | |

| Trend | BiLSTM | 0.0071 | 0.0085 | 0.7512 | 0.9685 |

| Lasso | 0.0206 | 0.0208 | 2.2167 | 0.8107 | |

| Ridge | 0.0159 | 0.0191 | 1.6686 | 0.8405 | |

| BiGRU | 0.0127 | 0.0151 | 1.3372 | 0.9006 | |

| SVR | 0.0175 | 0.0223 | 1.8298 | 0.7816 |

| Strategy | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BiGRU | 0.8463 | 0.9174 | 1.8554 | 0.8786 |

| 2. ICEEMDAN-BiGRU | 0.5367 | 0.6582 | 1.1922 | 0.9375 |

| 3. XGBoost | 1.1037 | 1.3472 | 2.3450 | 0.7382 |

| 4. ICEEMDAN-XGBoost | 0.9343 | 1.0751 | 2.0605 | 0.8333 |

| 5. BiLSTM | 0.9697 | 1.0358 | 2.0781 | 0.8453 |

| 6. ICEEMDAN-BiLSTM | 0.6186 | 0.7092 | 1.3161 | 0.9275 |

| 7. Ensemble forecasting model | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 |

| Strategy | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Textual features | 0.7629 | 0.8653 | 1.6546 | 0.8920 |

| 2. Financial features | 0.6150 | 0.7417 | 1.3122 | 0.9207 |

| 3. Financial features and LDA | 0.5355 | 0.6244 | 1.1443 | 0.9438 |

| 4. Financial features and SENTI | 0.4915 | 0.5812 | 1.0670 | 0.9513 |

| 5. Financial features and CNN | 0.4709 | 0.5872 | 1.0152 | 0.9503 |

| 6. Financial features and LDA and SENTI | 0.4349 | 0.5024 | 0.9345 | 0.9636 |

| 7. Financial features and LDA and CNN | 0.4965 | 0.5669 | 1.0238 | 0.9537 |

| 8. Financial features and SENT I and CNN | 0.4623 | 0.5431 | 1.0137 | 0.9582 |

| 9. Financial features and Textual features | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 |

| Strategy | MAE | MSE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Textual features | 0.000 *** (7.3406) | 0.000 *** (8.0308) | 0.000 *** (8.3422) |

| 3. Financial features and LDA | 0.000 *** (−5.9047) | 0.000 *** (−4.6703) | 0.000 *** (−4.6214) |

| 4. Financial features and SENTI | 0.000 *** (−7.5732) | 0.000 *** (−6.7335) | 0.000 *** (−6.7103) |

| 5. Financial features and CNN | 0.000 *** (−5.7479) | 0.000 *** (−5.5689) | 0.000 *** (−5.3605) |

| 6. Financial features and LDA and SENTI | 0.000 *** (−8.1214) | 0.000 *** (−8.2145) | 0.000 *** (−8.1728) |

| 7. Financial features and LDA and CNN | 0.000 *** (−6.7421) | 0.000 *** (−6.6287) | 0.000 *** (−6.4258) |

| 8. Financial features and SENTI and CNN | 0.000 *** (−7.9521) | 0.000 *** (−8.1354) | 0.000 *** (−7.8753) |

| 9. Financial features and Textual features | 0.000 *** (−9.9290) | 0.000 *** (−9.6369) | 0.000 *** (−9.6246) |

| Strategy | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Textual features | 0.8103 | 0.9025 | 1.7453 | 0.8652 |

| 2. Financial features | 0.6508 | 0.7812 | 1.3620 | 0.8935 |

| 3. Financial features and LDA | 0.5692 | 0.6618 | 1.2045 | 0.9190 |

| 4. Financial features and SENTI | 0.5286 | 0.6147 | 1.1284 | 0.9295 |

| 5. Financial features and CNN | 0.5037 | 0.6230 | 1.0756 | 0.9282 |

| 6. Financial features and LDA and SENTI | 0.4695 | 0.5440 | 0.9862 | 0.9457 |

| 7. Financial features and LDA and CNN | 0.5228 | 0.5994 | 1.0865 | 0.9310 |

| 8. Financial features and SENTI and CNN | 0.4896 | 0.5760 | 1.0640 | 0.9371 |

| 9. Financial features and Textual features | 0.4025 | 0.4935 | 0.8582 | 0.9508 |

| Strategy | MAE | MSE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Textual features | 0.000 *** (7.1205) | 0.000 *** (7.8053) | 0.000 *** (8.0147) |

| 3. Financial features and LDA | 0.000 *** (−5.4821) | 0.000 *** (−4.3286) | 0.000 *** (−4.3025) |

| 4. Financial features and SENTI | 0.000 *** (−7.1154) | 0.000 *** (−6.3019) | 0.000 *** (−6.2857) |

| 5. Financial features and CNN | 0.000 *** (−5.3612) | 0.000 *** (−5.1627) | 0.000 *** (−4.9984) |

| 6. Financial features and LDA and SENTI | 0.000 *** (−7.8123) | 0.000 *** (−7.9341) | 0.000 *** (−7.9152) |

| 7. Financial features and LDA and CNN | 0.000 *** (−6.3284) | 0.000 *** (−6.2138) | 0.000 *** (−6.0243) |

| 8. Financial features and SENTI and CNN | 0.000 *** (−7.5027) | 0.000 *** (−7.6850) | 0.000 *** (−7.4571) |

| 9. Financial features and Textual features | 0.000 *** (−9.2146) | 0.000 *** (−8.9961) | 0.000 *** (−8.9783) |

| Region | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hubei | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 |

| Guangdong | 0.8288 | 1.0097 | 1.1335 | 0.9733 |

| Shanghai | 0.6512 | 0.8163 | 1.0278 | 0.9752 |

| Region | Reproportion | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hubei | 4:1 | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 |

| 5:1 | 0.3391 | 0.4583 | 0.7480 | 0.9730 | |

| 6:1 | 0.4016 | 0.5075 | 0.8794 | 0.9699 | |

| Guangdong | 4:1 | 0.8288 | 1.0097 | 1.1335 | 0.9733 |

| 5:1 | 0.6363 | 1.0472 | 0.9298 | 0.9749 | |

| 6:1 | 0.7518 | 1.1602 | 1.1036 | 0.9730 | |

| Shanghai | 4:1 | 0.6512 | 0.8163 | 1.0278 | 0.9752 |

| 5:1 | 0.6576 | 0.8656 | 1.0216 | 0.9739 | |

| 6:1 | 0.7192 | 0.8374 | 1.1253 | 0.9731 |

| Region | Horizon | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hubei | H = 1 | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 |

| H = 3 | 0.3880 | 0.4740 | 0.8278 | 0.9676 | |

| H = 7 | 0.3415 | 0.4468 | 0.7410 | 0.9713 | |

| Guangdong | H = 1 | 0.8288 | 1.0097 | 1.1335 | 0.9733 |

| H = 3 | 0.8924 | 1.0263 | 1.2023 | 0.9724 | |

| H = 7 | 0.8041 | 1.0516 | 1.0822 | 0.9711 | |

| Shanghai | H = 1 | 0.6512 | 0.8163 | 1.0278 | 0.9752 |

| H = 3 | 0.7430 | 0.8494 | 1.2402 | 0.9731 | |

| H = 7 | 0.6239 | 0.8257 | 0.9780 | 0.9747 |

| Model Type | Model | MAE | RMSE | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear machine-learning models | Lasso | 1.2346 | 1.2878 | 2.6534 | 0.7608 |

| Ridge | 1.1603 | 1.2916 | 2.5255 | 0.7594 | |

| Decision tree model | RF | 1.0935 | 1.2955 | 2.3401 | 0.7580 |

| XGBoost | 1.1037 | 1.3472 | 2.3450 | 0.7382 | |

| Neural network model | MLP | 0.9333 | 1.1253 | 2.0040 | 0.8174 |

| BiGRU | 0.8463 | 0.9174 | 1.8554 | 0.8786 | |

| BiLSTM | 0.9697 | 1.0358 | 2.0781 | 0.8453 | |

| Support vector machine | SVM | 1.0945 | 1.2417 | 2.3458 | 0.7776 |

| Econometric model | ARIMA | 0.9262 | 1.3396 | 2.0292 | 0.7407 |

| AR | 0.9828 | 1.4128 | 2.1544 | 0.7116 | |

| Ensemble forecasting model | 0.3748 | 0.4611 | 0.8047 | 0.9693 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yang, T.; Gong, X.; Lyu, Z. Carbon Trading Price Forecasting Based on Multidimensional News Text and Decomposition–Ensemble Model: The Case Study of China’s Pilot Regions. Forecasting 2025, 7, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040072

Wang X, Liu Y, Guo Z, Yang T, Gong X, Lyu Z. Carbon Trading Price Forecasting Based on Multidimensional News Text and Decomposition–Ensemble Model: The Case Study of China’s Pilot Regions. Forecasting. 2025; 7(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xu, Yingjie Liu, Zhenao Guo, Tengfei Yang, Xu Gong, and Zhichong Lyu. 2025. "Carbon Trading Price Forecasting Based on Multidimensional News Text and Decomposition–Ensemble Model: The Case Study of China’s Pilot Regions" Forecasting 7, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040072

APA StyleWang, X., Liu, Y., Guo, Z., Yang, T., Gong, X., & Lyu, Z. (2025). Carbon Trading Price Forecasting Based on Multidimensional News Text and Decomposition–Ensemble Model: The Case Study of China’s Pilot Regions. Forecasting, 7(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast7040072