Toward Expanding the Utilisation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Rare Earth Recovery from Primary Ores and Process Tailings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Characterisation

2.2. Reagent Preparation

2.3. Leaching Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Preparation and Characterisation

3.2. Leaching Experiments

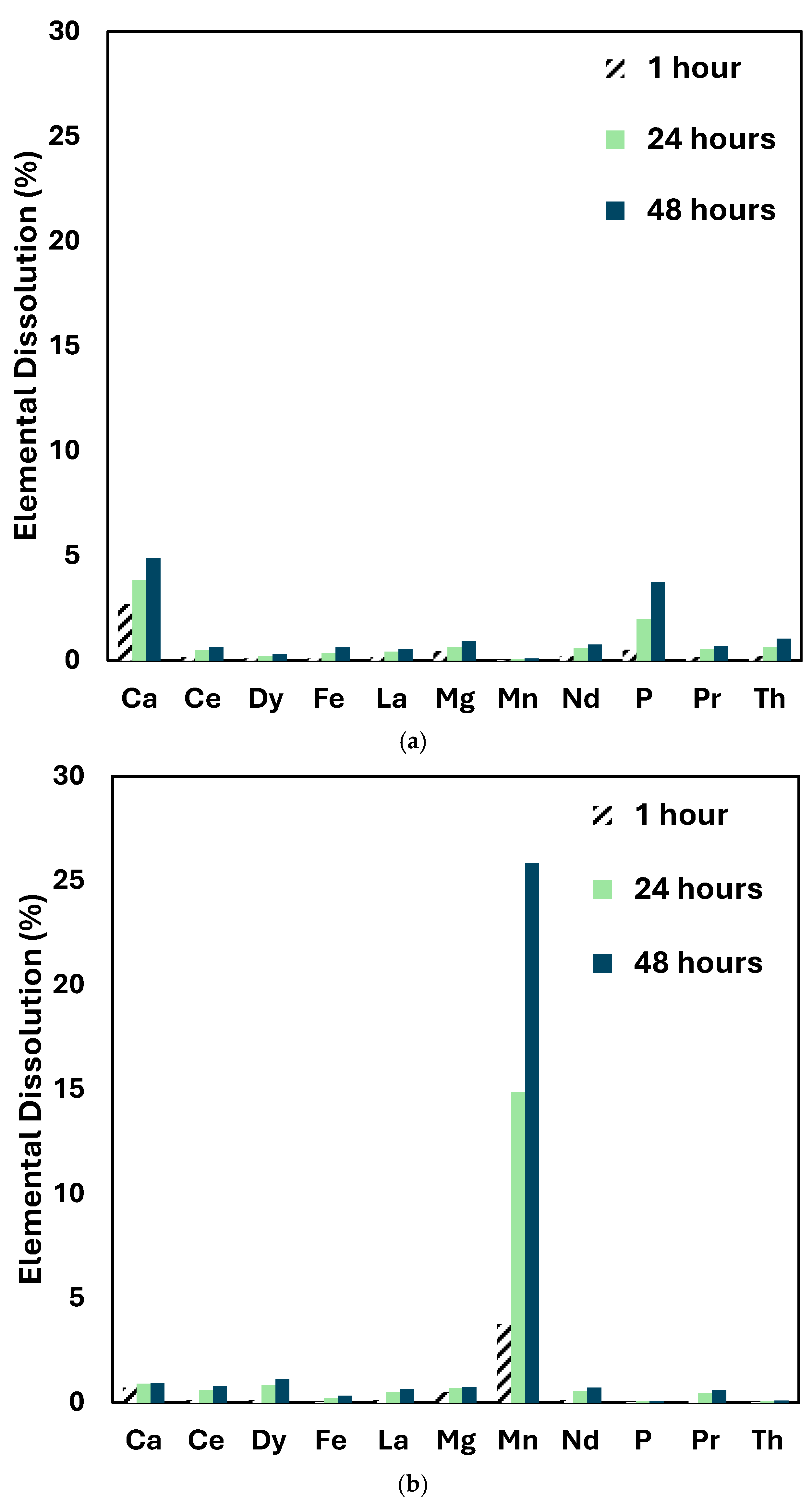

3.2.1. Reline

3.2.2. Ethaline

3.2.3. EG-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents

3.2.4. Vat Leaching

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, C.K.; Krishnamurthy, N. Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths. Int. Mater. Rev. 1992, 37, 197–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Departmernt of Industry, Science and Resources, Commonwealth Government of Australia. Australian Critical Minerals Strategy Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030; Departmernt of Industry, Science and Resources, Commonwealth Government of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. In European Commission Fifth List 2023 of Critical Raw Materials for the EU; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yamini, K.; Dyer, L. Extraction of Rare Earth Elements from Low-Grade Ore and Process Waste Stream. In Proceedings of the 26th World Mining Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 26–29 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu-Rahkama, R.; Kinnunen, P. Tailings Valorisation: Opportunities to Secure Rare Earth Supply and Make Mining Environmentally More Sustainable. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 520, 146147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K.; Jones, P.T.; Blanpain, B.; Van Gerven, T.; Pontikes, Y. Towards Zero-Waste Valorisation of Rare-Earth-Containing Industrial Process Residues: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K.; Jones, P.T. Solvometallurgy: An Emerging Branch of Extractive Metallurgy. J. Sustain. Metall. 2017, 3, 570–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanda, H.; Dai, Y.; Wilson, E.G.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Green Solvents from Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents to Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2018, 21, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel Solvent Properties of Choline Chloride/Urea Mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 39, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Database of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Physical Properties: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 121899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Munro, H.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Preparation of Novel, Moisture-Stable, Lewis-Acidic Ionic Liquids Containing Quaternary Ammonium Salts with Functional Side Chains. Chem. Commun. 2001, 7, 2010–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zheng, G.-W.; Zong, M.-H.; Li, N.; Lou, W.-Y. Recent Progress on Deep Eutectic Solvents in Biocatalysis. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Boothby, D.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K. Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed between Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids: Versatile Alternatives to Ionic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9142–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Martins, M.A.R.; Silva, L.P.; Schaeffer, N.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Phenolic Hydrogen Bond Donors in the Formation of Non-Ionic Deep Eutectic Solvents: The Quest for Type V DES. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10253–10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Type V Deep Eutectic Solvents: Design and Applications. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 35, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Royer, S.; Jérôme, F. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Syntheses, Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7108–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Lan, X.; Zhao, X.; Mou, H.; Mu, T. A Strategy for the Dissolution and Separation of Rare Earth Oxides by Novel Brønsted Acidic Deep Eutectic Solvents. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4748–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Xiao, C. Efficient Recovery of End-of-Life Ndfeb Permanent Magnets by Selective Leaching with Deep Eutectic Solvents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10370–10379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezari-Zarandi, A.; Larachi, F. Selective Dissolution of Rare-Earth Element Carbonates in Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Rare Earths 2019, 37, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateli, I.M.; Abbott, A.P.; Binnemans, K.; Rodriguez Rodriguez, N. Recovery of Yttrium and Europium from Spent Fluorescent Lamps Using Pure Levulinic Acid and the Deep Eutectic Solvent Levulinic Acid-Choline Chloride. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 28879–28890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, M.; Swadzba-Kwasny, M.; Holbrey, J.D. Thermal Properties of Choline Chloride/Urea System Studied under Moisture-Free Atmosphere. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 5248–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.Q.; Abbasi, N.M.; Anderson, J.L. Deep Eutectic Solvents in Separations: Methods of Preparation, Polarity, and Applications in Extractions and Capillary Electrochromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1633, 461613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamini, K.; Dyer, L. Technospheric Mining of Rare Earth Elements from Acid-Crack Leach Tailings. In Proceedings of the XXXI Internation Mineral Processing Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 29 September–3 October 2024; pp. 1237–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Lazo, D.E.; Dyer, L.G.; Alorro, R.D.; Browner, R. Treatment of Monazite by Organic Acids II: Rare Earth Dissolution and Recovery. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 179, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | HBA | HBD | Formula | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Quaternary Ammonium salts of chloroaluminate/imidazolium | Metal Chlorides like copper chloride, ferrous chloride | Cat+X−zMClx (M = Zn, Sn, Fe, Al, Ga, In) | [8,11,12] |

| Type II | Quaternary Ammonium salts | Metal Halide Hydrates | Cat+X−zMClx.yH2O (M = Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Fe) | [8,11,13] |

| Type III | Quaternary Ammonium, sulphonium, and phosphonium salts | Organic molecules like carboxylic acid, amide, or polyol | Cat+X−zRZ (Z = CONH2, COOH, OH) | [10,11,14] |

| Type IV | Metal Halides | HBD | MClx + RZ (M = Zn, Al and Z = CONH2, OH) | [8,11] |

| Type V | Non-ionic | Non-ionic | Non-ionic | [11,15,16] |

| HBA | Tm (°C) | HBD | Tm (°C) | Eutectic Temperature (°C) | Molar Ratio | Viscosity (cP) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choline Chloride (ChCl) | 302 | Urea | 134 | 12, 32 | 1:2 | 750 (25 °C), 169 (40 °C) | [10,17,22] |

| Choline Chloride (ChCl) | 302 | Ethylene Glycol | −13 | −66 | 1:2 | 36 | [17,23] |

| Ethylene Glycol | −13 | Malonic Acid | 135 | −102.7 | 4:1 | - | [18] |

| Ethylene Glycol | −13 | Maleic Acid | 130.5 | −98.9 | 4:1 | - | [18] |

| Composition (%) | Al | Ca | Ce | Fe | La | Mn | Nd | P | Pr | Th | T-REE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ore A | 1.75 | 0.37 | 3.24 | 35.8 | 1.58 | 2.66 | 1.67 | 2.41 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 6.94 |

| Ore B | 2.68 | 0.22 | 3.21 | 26.5 | 1.68 | 0.53 | 1.59 | 2.21 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 6.87 |

| Float Tails | 1.73 | 0.30 | 2.17 | 33.8 | 0.96 | 2.84 | 1.02 | 1.22 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 4.39 |

| ACL Residue | 2.42 | 1.63 | 1.23 | 20.7 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.74 | 8.16 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 2.79 |

| Feed Samples | Ore A | Ore B | Float Tails | ACL Residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p80 (µm) | 56.6 | 70.9 | 34.8 | - |

| Composition (%) | Al | Ca | Ce | Fe | La | Mn | Nd | P | Pr | Th | T-REE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ore A | 0.09 | 8.68 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.39 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Ore B | 0.15 | 23.75 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Float Tails | 0.08 | 2.87 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| ACL Residue | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.20 |

| Composition (%) | Ce | Dy | Fe | La | Mn | Nd | P | Pr | Th | T-REE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ore B | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 96.8 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| ACL Residue | 4.35 | 7.49 | 0.80 | 7.12 | 43.45 | 4.86 | 0.11 | 4.00 | 2.04 | 5.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamini, K.; Dyer, L.G.; Tadesse, B.; Alorro, R.D. Toward Expanding the Utilisation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Rare Earth Recovery from Primary Ores and Process Tailings. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040111

Yamini K, Dyer LG, Tadesse B, Alorro RD. Toward Expanding the Utilisation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Rare Earth Recovery from Primary Ores and Process Tailings. Clean Technologies. 2025; 7(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamini, K., Laurence G. Dyer, Bogale Tadesse, and Richard D. Alorro. 2025. "Toward Expanding the Utilisation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Rare Earth Recovery from Primary Ores and Process Tailings" Clean Technologies 7, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040111

APA StyleYamini, K., Dyer, L. G., Tadesse, B., & Alorro, R. D. (2025). Toward Expanding the Utilisation of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Rare Earth Recovery from Primary Ores and Process Tailings. Clean Technologies, 7(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040111