Modeling Moisture Factors in Grassland Fire Danger Index for Prescribed Fire Management in the Great Plains

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Fire Danger Indexes

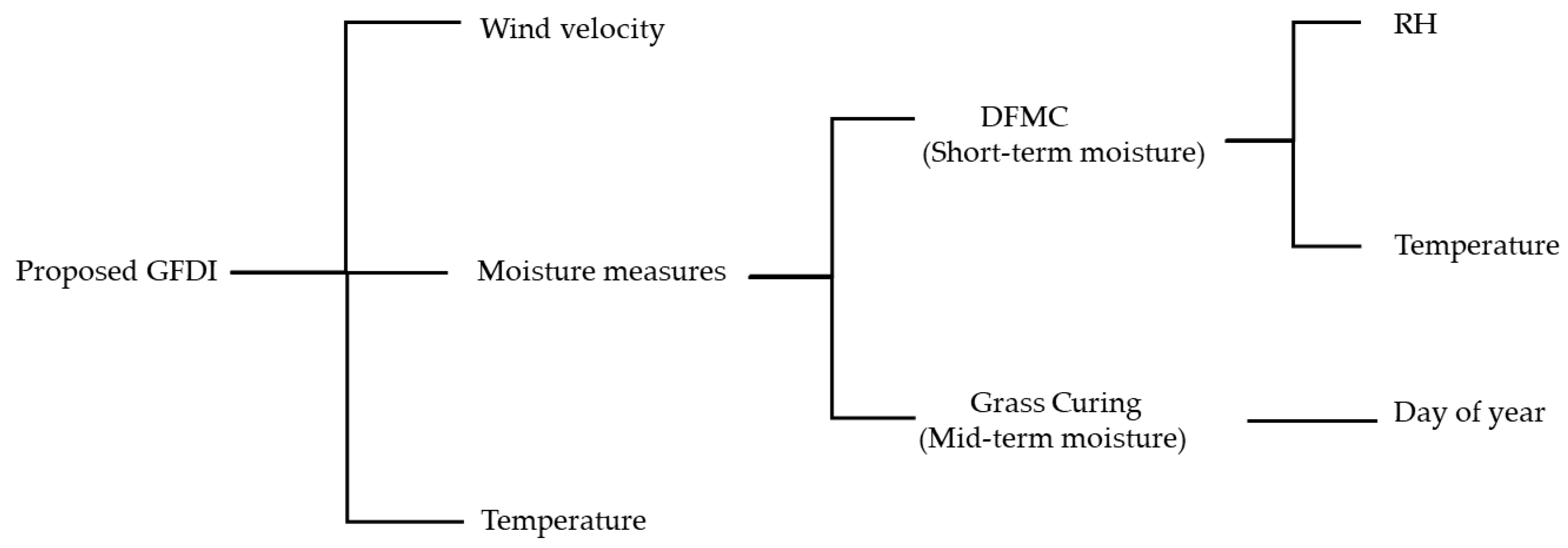

1.2. Proposed GFDI for the Great Plains, USA

1.3. Existing DFMC Models

1.4. Existing Grass Curing Assessment Methods

1.5. Objective of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Weather and Fuel Data

2.2. Wildfire Data

2.3. Development of the Sub-Models

3. Results

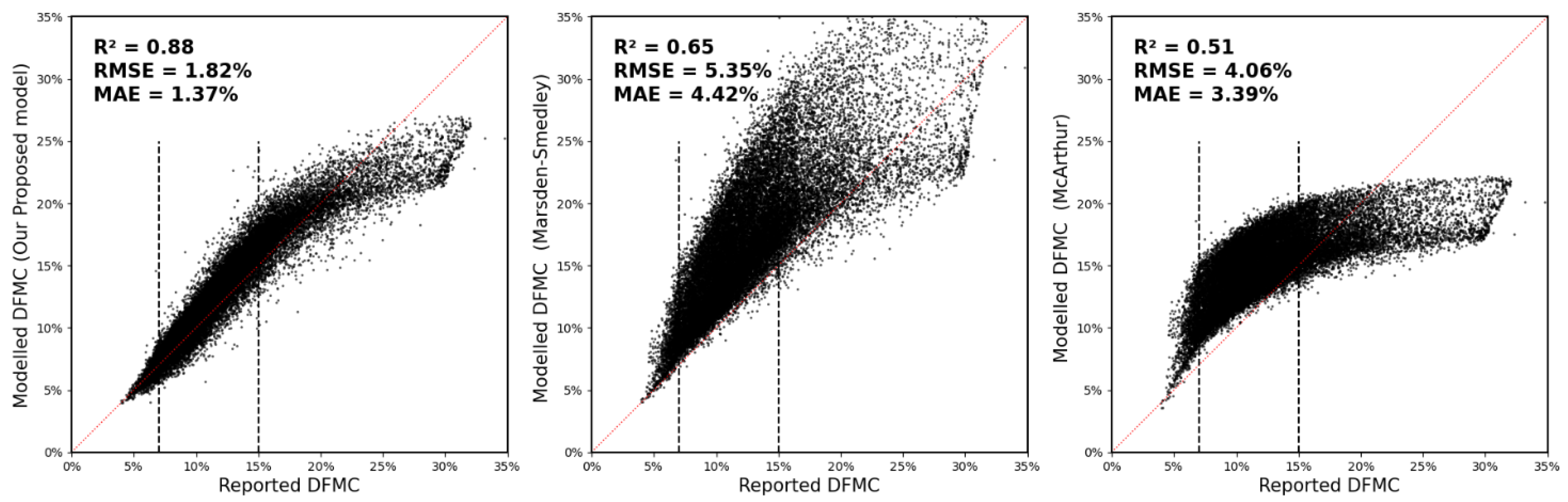

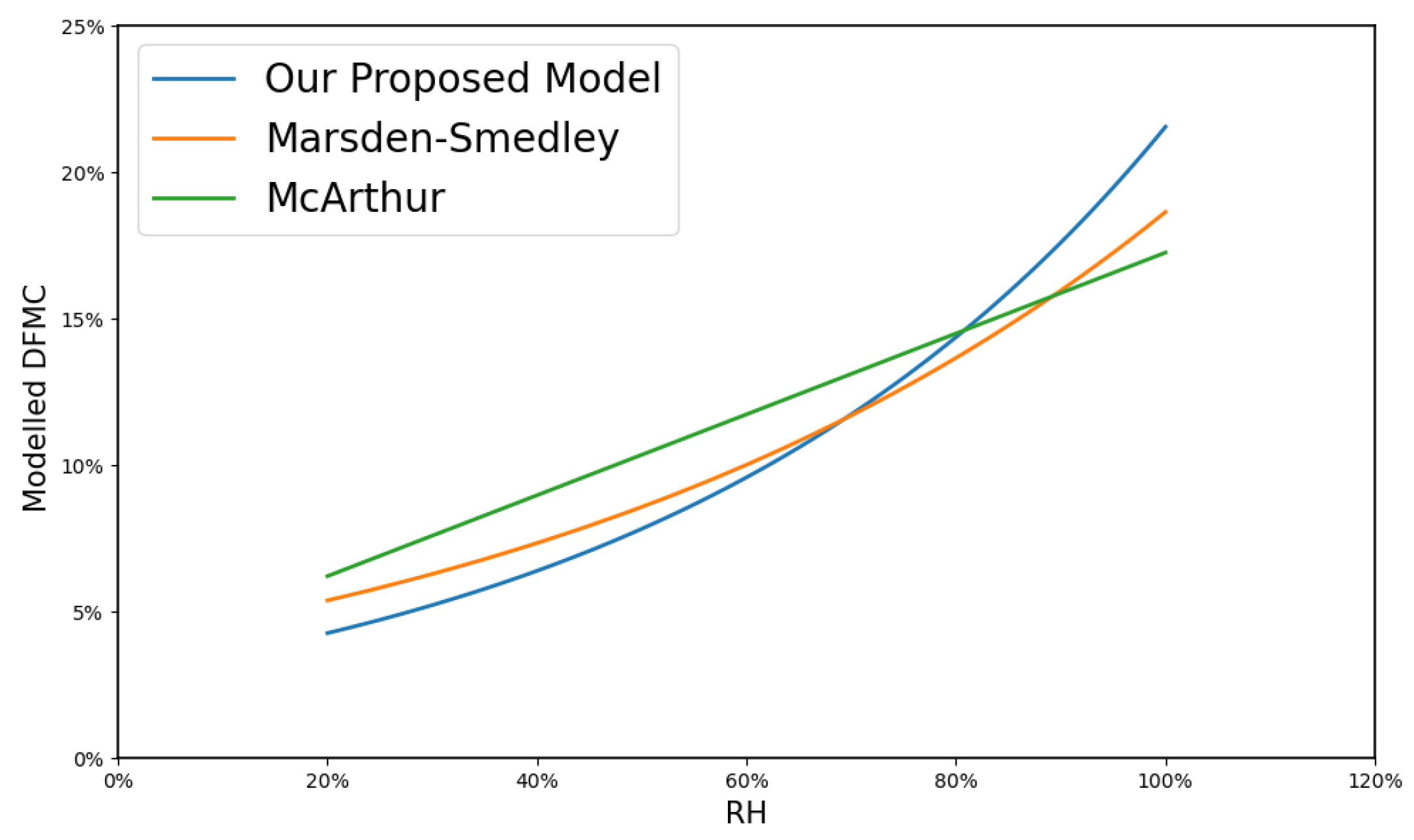

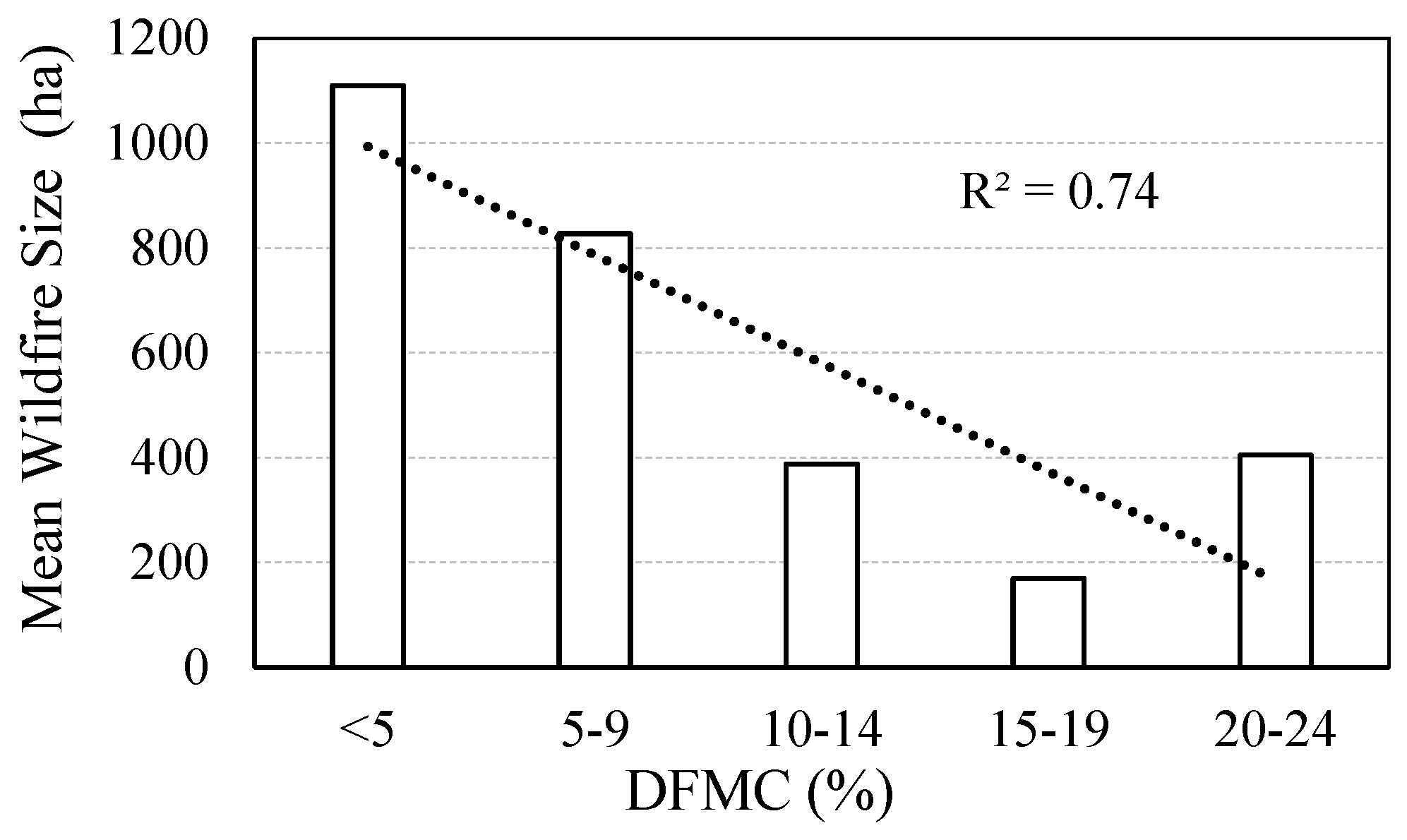

3.1. The DFMC Sub-Model

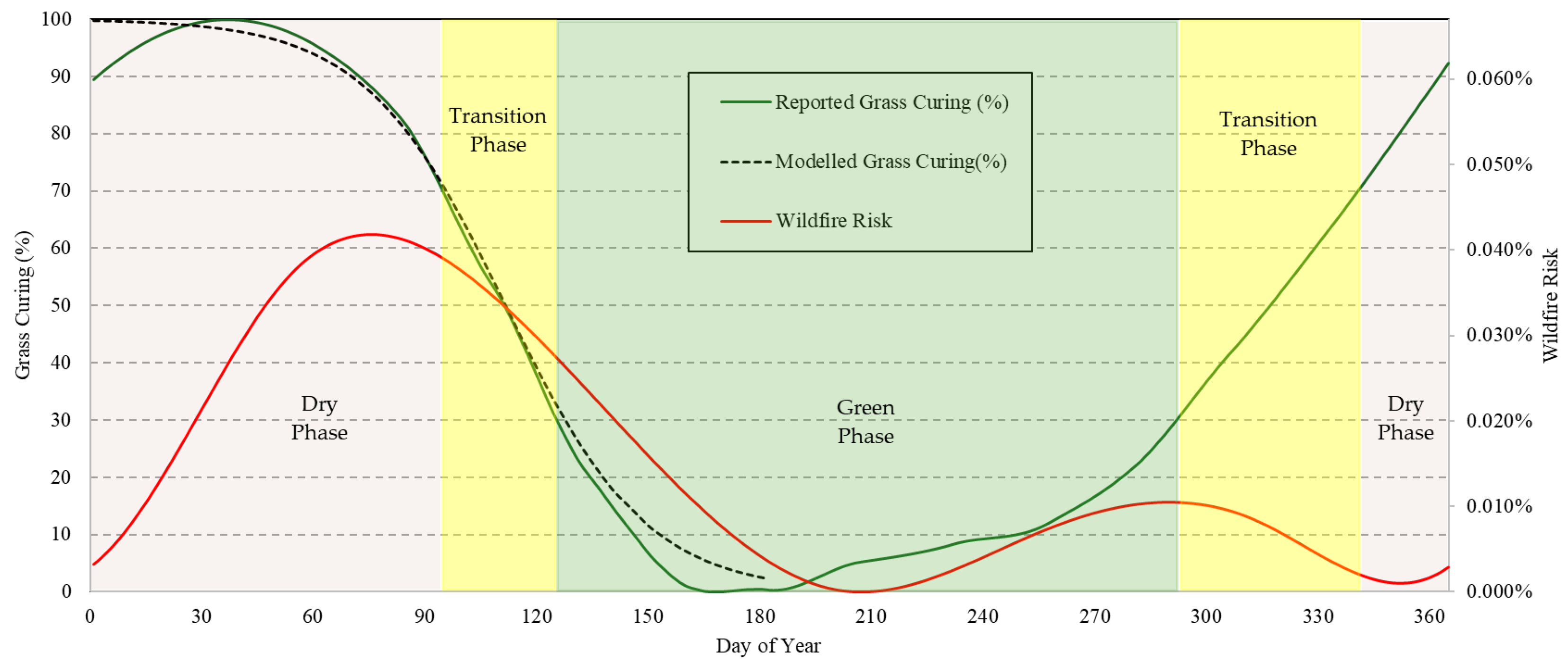

3.2. The Grass Curing Sub-Model

4. Discussion

4.1. DFMC as a Daily Fire Risk Factor

4.2. Grass Curing as a Seasonal Fire Risk Factor

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GFDI | Grassland Fire Danger Index |

| DOY | Day of year |

| KBDI | Keetch–Byram Drought Index |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- McEowen, R.A.; Baldwin, C. Kansas Prescribed Burning—Rules and Regulations; MF3601; Kansas State University: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Okafor, I.O.; George, M.B. Characterizing risks for wildfires and prescribed fires in the Great Plains. Fire 2025, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, T.D.; Clarke, H.; Cirulis, B.; Boer, M.M.; Price, O.F.; Bradstock, R.A. Cost-effective prescribed burning solutions vary between landscapes in eastern Australia. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky Jerry, D.; Stubbendieck James, L.; Mitchell Rob, B. Conducting a Prescribed Burn and Prescribed Burning Checklist; Nebraska Forest Service: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2010; Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebforestpubs/23 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Schreck, M.B.; Howerton, P.J.; Cook, K.R. Adapting Australia’s Grassland Fire Danger Index for the United States’ Central Plains; 10-02; Central Region Technical Attachment; NWS Weather Forecast Offices: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2010.

- Sharples, J.J.; McRae, R.H.D.; Weber, R.O.; Gill, A.M. A simple index for assessing fire danger rating. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, V.; Sfetsos, A.; Vlachogiannis, D.; Gounaris, N. Fire Weather Index (FWI) classification for fire danger assessment applied in Greece. Tethys J. Weather Clim. West. Mediterr. 2018, 15, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, D.; Alexander, M. Glossary of Forest Fire Management Terms, 4th ed.; National Research Council of Canada, Canadian Committee on Forest Fire Management: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1987; Publication NRCC No. 26516. [Google Scholar]

- Podschwit, H.; Jolly, W.; Alvarado, E.; Markos, A.; Verma, S.; Barreto-Rivera, S.; Tobón-Cruz, C.; Ponce-Vigo, B. Effects of fire danger indexes and land cover on fire growth in Peru. EGUsphere 2022, preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Cocero, D. Remote sensing of large wildfires in the European Mediterranean Basin. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 60, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Cocero, D.; Riaño, D. Design of an empirical index to estimate fuel moisture content from NOAA-AVHRR images in forest fire danger studies. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.L.; Bradshaw, L.S. FIRES: Fire Information Retrieval and Evaluation System; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Logan, UT, USA, 1997. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_int/int_gtr367.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Schoenberg, F.P.; Chang, C.H.; Keeley, J.E.; Pompa, J.; Woods, J.; Xu, H. A critical assessment of the burning index in Los Angeles County, California. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2007, 16, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keetch, J.J.; Byram, G.M. A Drought Index for Forest Fire Control; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 1968; Volume 38.

- Carlson, J.D.; Burgan, R.E.; Engle, D.M.; Greenfield, J.R. The Oklahoma fire danger model: An operational tool for mesoscale fire danger rating in Oklahoma. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2002, 11, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A. Review of the operational calculation of McArthur’s drought factor; Client Report Number 921; CSIRO Forestry and Forest Products: Canberra, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taufik, M.; Setiawan, B.I.; van Lanen, H.A. Modification of a fire drought index for tropical wetland ecosystems by including water table depth. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 203, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dharssi, I. Evaluation of daily soil moisture deficit used in Australian forest fire danger rating system. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 259, 685–697. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, E.S.; Levi, M.R.; Achieng, K.O.; Bolten, J.D.; Carlson, J.D.; Coops, N.C.; Holden, Z.A.; Magi, B.I.; Rigden, A.J.; Ochsner, T.E. Using soil moisture information to better understand and predict wildfire danger: A review of recent developments and outstanding questions. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2022, 32, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucinski, M.P.; Tartaglia, E.; Huston, C.; Stephenson, A.G.; Dunstall, S.; McCarthy, N.F.; Deutsch, S. Exploring the influence of the Keetch–Byram Drought Index and McArthur’s Drought Factor on wildfire incidence in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, M.J.; Johnson, M.B.; Forthun, G. Near-real time mapping of Keetch–Byram Drought Index in the southeastern United States. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2002, 11, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkele, K.; Mills, G.A.; Beard, G.; Jones, D.A. National gridded drought factors and comparison of two soil moisture deficit formulations used in prediction of Forest Fire Danger Index in Australia. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 2006, 55, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, A. Grassland Fire Danger Meter. 2008. Available online: http://www.csiro.au/products/GrassFireSpreadMeter.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Noble, I.R.; Gill, A.M.; Bary, G.A.V. McArthur’s fire-danger meters expressed as equations. Aust. J. Ecol. 1980, 5, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purton, C.M. Equations for the McArthur Mark 4 Grassland Fire Danger Meters; Meteorological Note 147; Bureau of Meteorology: Melbourne, Australia, 1982.

- Cheney, P.; Sullivan, A. Grassfires: Fuel, Weather and Fire Behaviour; Csiro Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis, J.J.; Matthews, S.; Fox-Hughes, P.; Grootemaat, S.; Heemstra, S.; Kenny, B.J.; Sauvage, S. Introduction to the Australian fire danger rating system. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, B.J.; Matthews, S.; Sauvage, S.; Grootemaat, S.; Hollis, J.J.; Fox-Hughes, P. Australian Fire Danger Rating System: Implementing Fire Behaviour Calculations to Forecast Fire Danger in a Research Prototype. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, I.O.; Liu, Z.; George, M.B. Quantifying and modeling wildland fire risk for prescribed fire management in the Great Plains. Fire Ecol. 2025, in press.

- Cruz, M.G.; Sullivan, A.L.; Gould, J.S.; Sims, N.C.; Bannister, A.J.; Hollis, J.J.; Hurley, R.J. Anatomy of a catastrophic wildfire: The Black Saturday Kilmore East fire in Victoria, Australia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 284, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.H.; Boer, M.M.; Resco de Dios, V.; Caccamo, G.; Bradstock, R.A. Large-scale, dynamic transformations in fuel moisture drive wildfire activity across southeastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 4229–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Grassland fire management in future climate. United_Nation_2021_Wildfires—A growing concern for sustainable development. Adv. Agron. 2010, 106, 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, N.R. A review of fine fuel moisture modelling. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 1991, 1, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.M. Water relations of forest fuels. In Forest Fires: Behavior and Ecological Effects; Johnson, E.A., Miyanishi, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 79–149. [Google Scholar]

- Yebra, M.; Dennison, P.E.; Chuvieco, E.; Riaño, D.; Zylstra, P.; Hunt, E.R., Jr.; Jurdao, S.; Kane, V.; Rothermel, R.C.; Roberts, D.A.; et al. A global review of remote sensing of live fuel moisture content for fire danger assessment: Moving towards operational products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 136, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, W.M.; Freeborn, P.H.; Page, W.G.; Butler, B.W. Severe fire danger index: A forecastable metric to inform firefighters and community wildfire risk management. Fire 2019, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.D.; Bradshaw, L.S.; Nelson, R.M., Jr.; Bensch, R.R.; Jabrzemski, R. Field evaluation of the Nelson dead fuel moisture model and comparisons with National Fire Danger Rating System (NFDRS) predictions. In Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Canmore, AB, Canada, 25–27 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, A.G. Weather and Grassland Fire Behavior; Forestry and Timber Bureau: Canberra, Australia, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden-Smedley, J.B.; Catchpole, W.R. Fire modelling in Tasmanian buttongrass moorlands. III. Dead fuel moisture. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2001, 10, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, T.J.; Chong, D.M.; Penman, T.D. Quantifying wildfire growth rates using smoke plume observations derived from weather radar. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2018, 27, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, M.F.; Millie, S. Grassland Curing Guide; Country Fire Authority, Community Safety Department: Melbourne, Australia, 2001.

- Anderson, S.A.; Anderson, W.R.; Hollis, J.J.; Botha, E.J. A simple method for field-based grassland curing assessment. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2011, 20, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M. The Vesta Mk 2 Rate of Fire Spread Model: A User’s Guide; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, N.P.; Gould, J.S.; Catchpole, W.R. The influence of fuel, weather and fire shape variables on fire spread in grasslands. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 1993, 3, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, W.R.; Wheeler, C.J. Estimating plant biomass: A review of techniques. Aust. J. Ecol. 1992, 17, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.; Wooster, M.J.; Lagoudakis, E. Annual and diurnal African biomass burning temporal dynamics. Biogeosciences 2009, 6, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.H.; Roberts, D.A.; Dennison, P.E. Mapping live fuel moisture with MODIS data: A multiple regression approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 4272–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Jones, S.; Grant, I.; Anderson, S. Assessment of grassland curing using field-based spectrometry and satellite imagery. In Innovations in Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry; Jones, S., Reinke, K., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, T.J.; Chong, D.M.; Tolhurst, K.G. Quantifying spatio-temporal differences between fire shapes: Estimating fire travel paths for the improvement of dynamic spread models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 46, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.M.; King, K.J.; Moore, A.D. Australian grassland fire danger using inputs from the GRAZPLAN grassland simulation model. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2010, 19, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, F.V.; Crawford, K.C.; Elliott, R.L.; Cuperus, G.W.; Stadler, S.J.; Johnson, H.L.; Eilts, M.D. The Oklahoma Mesonet: A technical overview. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1995, 12, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, R.A.; Fiebrich, C.; Crawford, K.C.; Elliott, R.L.; Kilby, J.R.; Grimsley, D.L.; Martinez, J.E.; Basara, J.B.; Illston, B.G.; Morris, D.A.; et al. Statewide monitoring of the mesoscale environment: A technical update on the Oklahoma Mesonet. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2007, 24, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, G.J.; Verbesselt, J.; Grant, I.F.; Anderson, S.A. Relative Greenness Index for Assessing Curing of Grassland Fuel. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaivaranont, W.; Evans, J.P.; Liu, Y.Y.; Sharples, J.J. Estimating Grassland Curing with Remotely Sensed Data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 1535–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Carlson, J.D.; Krueger, E.S.; Engle, D.M.; Twidwell, D.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Patrignani, A.; Feng, L.; Ochsner, T.E. Soil Moisture as an Indicator of Growing-Season Herbaceous Fuel Moisture and Curing Rate in Grasslands. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2021, 30, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S. Robust locally-weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.C. Spatial Wildfire Occurrence Data for the United States, 1992–2020 [FPA_FOD_20221014], 6th ed.; Forest Service Research Data Archive: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. Tigris: An R Package to Access and Work with Geographic Data from the US Census Bureau. R J. 2016, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 2018, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieszen, L.L.; Reed, B.C.; Bliss, N.B.; Wylie, B.K.; DeJong, D.D. NDVI, C3 and C4 production, and distributions in Great Plains grassland land cover classes. Ecol. Appl. 1997, 7, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, H.; Satriawan, T.W.; Tian, J.; Zhao, R.; Keenan, T.F.; Griffith, D.M.; Sitch, S.; Smith, N.G.; Still, C.J. Mapping the global distribution of C4 vegetation using observations and optimality theory. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, C.J.; Berry, J.A.; Collatz, G.J.; DeFries, R.S. Global distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation: Carbon cycle implications. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2003, 17, 6-1–6-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wylie, B.K.; Tieszen, L.L. Phenology-assisted classification of C3 and C4 grasses in the U.S. Great Plains. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 135, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrilla, C.A.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Derner, J.D.; Knapp, A.K.; Reichmann, L.G.; Wilcox, K.R.; Collins, S.L. Divergent climate impacts on C3 versus C4 grasses imply widespread 21st century shifts in grassland functional composition. Divers. Distrib. 2023, 29, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.W.; Harrison, A.T. Species distribution and community organization in Nebraska Sandhills mixed-prairie as influenced by plant/soil-water relationships. Oecologia 1982, 52, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, W.H.; Volesky, J.D.; Bauer, D.; Smart, A.J.; Mousel, E.M. Plant community patterns on upland prairie in the eastern Sandhills of Nebraska. Prairie Nat. 2000, 32, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

| Date 1 | Grass Curing | Landscape Features | Photo 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry phase | Before Jan 3rd | Close to 100% | Grass is fully cured. Stalks are dry and bleached, seed heads are empty, and stems are brittle with no moisture. |  |

| March 1st–2nd | 90% | The landscape is still largely dry and straw-colored, with early signs of green-up. |  | |

| March 15th–16th | 70% | The landscape remains mostly dry and straw-colored. |  | |

| Transition phase | April 15th–16th | 50% | Green-up is at the midpoint. The landscape has a mix of cured and uncured grasses. |  |

| Green phase | May 10th–11th | 30% | All grasses are almost green. |  |

| After June 23rd | Less than 10% | All the grass is fully green. |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

George, M.B.; Liu, Z.; Okafor, I.O. Modeling Moisture Factors in Grassland Fire Danger Index for Prescribed Fire Management in the Great Plains. Fire 2025, 8, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120469

George MB, Liu Z, Okafor IO. Modeling Moisture Factors in Grassland Fire Danger Index for Prescribed Fire Management in the Great Plains. Fire. 2025; 8(12):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120469

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorge, Mayowa B., Zifei Liu, and Izuchukwu O. Okafor. 2025. "Modeling Moisture Factors in Grassland Fire Danger Index for Prescribed Fire Management in the Great Plains" Fire 8, no. 12: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120469

APA StyleGeorge, M. B., Liu, Z., & Okafor, I. O. (2025). Modeling Moisture Factors in Grassland Fire Danger Index for Prescribed Fire Management in the Great Plains. Fire, 8(12), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120469