Comparative Analysis of Impregnation Methods for Polyimide-Based Prepregs: Insights from Industrial Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- o

- The polyimide (PI) resin in powder form was supplied by TÜBİTAK (TÜBİTAK Marmara Research Center, Gebze, Kocaeli, Turkey). This resin was specifically developed for high-performance prepreg applications and represents a partially imidized PI pre-polymer. According to the supplier, the general specification range for this PI pre-polymer family is Mn = 1500–20,000 g/mol, while the specific batch used in this study has Mn in the range of 1500–3000 g/mol. [Due to confidentiality restrictions, detailed compositional information cannot be disclosed].

- o

- Solvent DMAC (dimethylacetamide, purity >99%, Sigma Aldrich), used for solvent-based impregnation.(was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

- o

- Reinforcements:

- o

- Carbon fibers 12 K, PAN-based, supplied by DowAksa (DowAksa, Gumussuyu, Istanbul, Turkey).

- o

- Woven carbon fabric, grammage of 200 gsm, was supplied by DowAksa (DowAksa, Gumussuyu, Istanbul, Turkey).

- o

- Release films and liners:

- o

- Silicone-coated paper (yellow, 90 gsm, double-sided coated), supplied by Excelitas Noblelight (Heraeus), Kleinostheim, Germany.

- o

- Silicone-coated paper (white, 90–92 gsm, single-sided coated), supplied by Tireks (Tireks, Prilep, North Macedonia)

- o

- Kapton® film (50 µm), supplied by Airtech Europe, Niederkorn, Luxembourg.

- o

- Polypropylene (PP) film (50 µm thick), supplied by Tubitak (TÜBİTAK Marmara Research Center, Gebze, Kocaeli, Turkey).

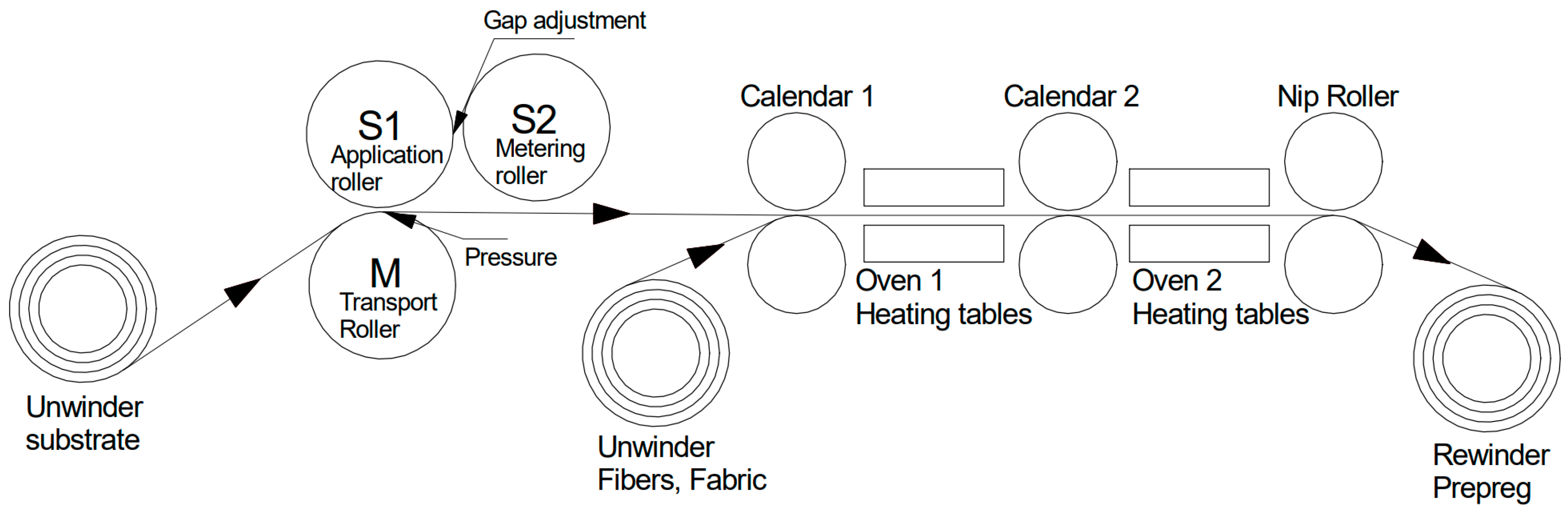

2.2. Experimental Setup

- o

- Unwinder and rewinder units with adjustable tension control;

- o

- Resin bath (for solvent process);

- o

- Three reverse roll coating system for hot-melt resin application;

- o

- Oven with temperature zones (80–150 °C);

- o

- Calender rollers (gap adjustable to 0.01 mm precision);

- o

- Lamination section with heated nip rolls.

2.3. Methods for Impregnation

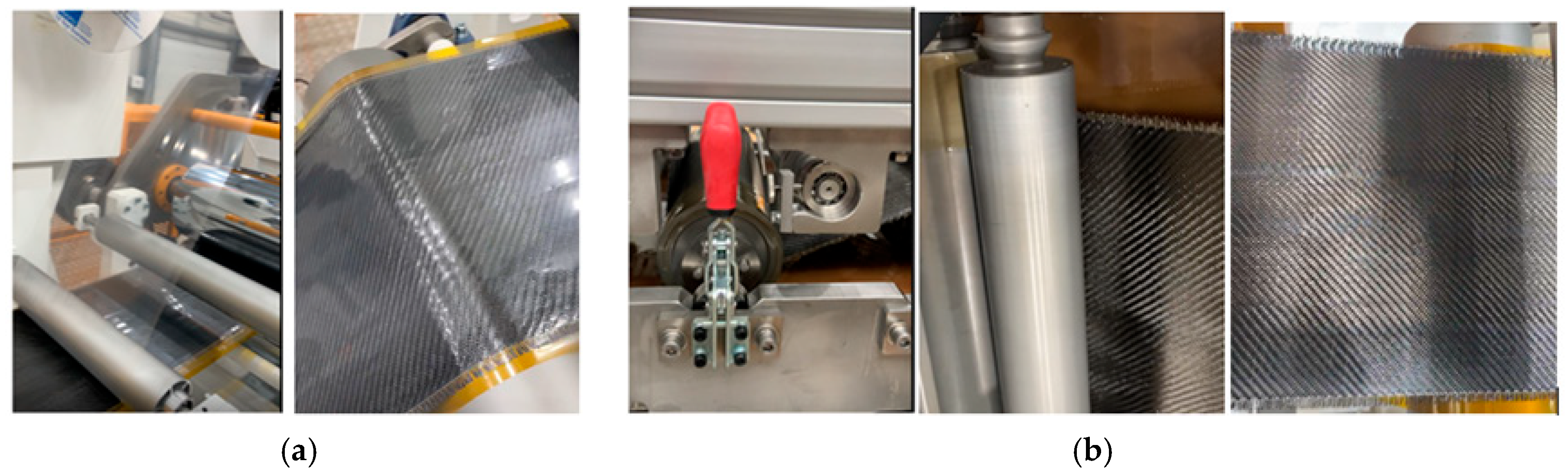

- The hot-melt method (presented in Figure 2) was conducted with composition of PI resin/DMAC = 70:30 (weight ratio). This ratio provided an optimal viscosity (~3000 mPa·s) for a film formation using the three-roll reverse coating unit, enabling uniform coating without excessive solvent retention. The viscosity of resin–hot-melt mixtures was measured using a Brookfield DV3T rheometer on preliminary samples to determine optimal processing ranges at 55 °C. In this case, DMAC was used only to decrease the resin viscosity in order for it to be more easily applied to C-fibers, as has previously been reported by other researchers as well [26]. The film formation and impregnation were carried out sequentially within the same production line, without intermediate storage or transfer. This configuration represents an in situ hot-melt process, where the resin film is formed and directly applied to the fibers in a single continuous operation.

- o

- Resin pre-melted and applied as thin film.

- o

- Impregnation into carbon fibers through heated calendering. The hot-melt film coating was carried out at a roller temperature of 55 °C, which ensured optimal resin flow and adhesion to the paper substrate. The subsequent drying and imidization stages were performed in two heating zones: in oven 1 at 100 °C and in oven 2 at 150 °C. In oven 2, an active ventilation system was engaged to facilitate the removal of residual solvent vapors and prevent their condensation on the film surface. Prior to entering oven 2, the upper paper liner was removed to allow unobstructed evaporation of the solvent. These controlled temperature and ventilation conditions provided uniform resin distribution and ensured that the volatile content remained below 1.5%.

- o

- Minimal solvent evaporation.

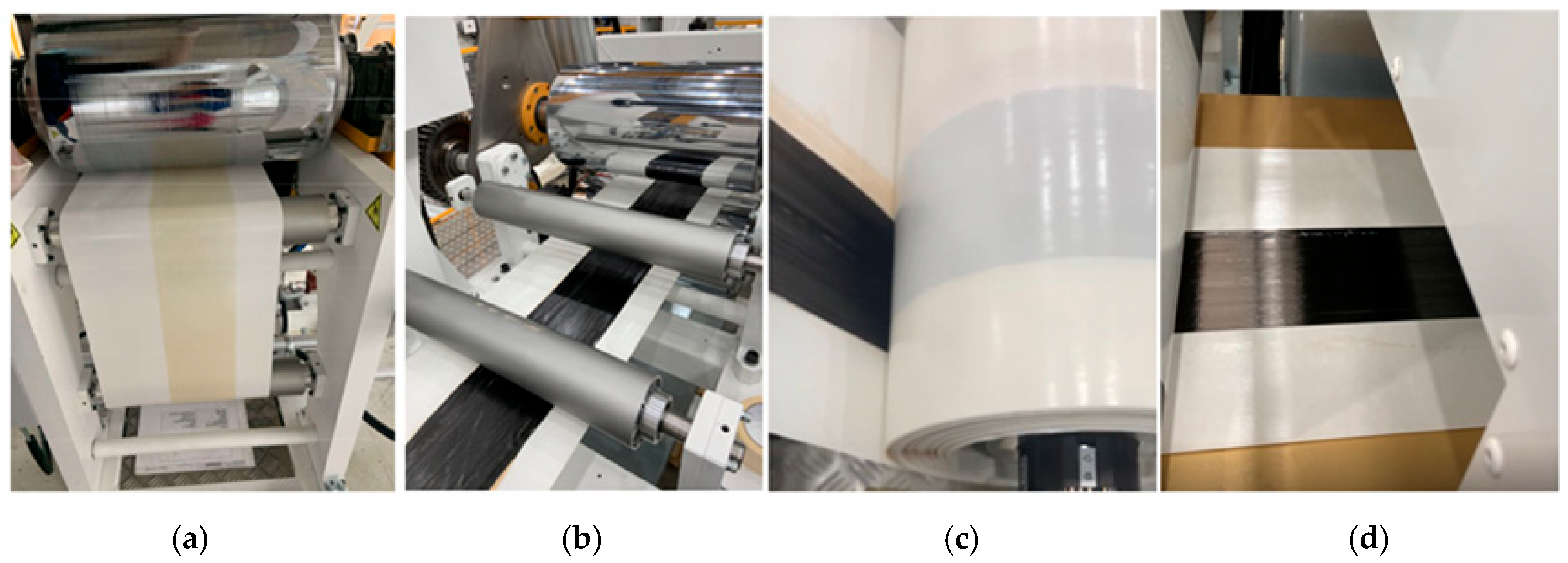

- Solvent-based method (shown in Figure 3): PI resin and DMAC (weight ratio of 50:50):

- o

- Carbon fibers/fabrics passed through resin bath;

- o

- Solvent evaporation in multi-zone oven (100–120 °C);

- o

- Final consolidation through heated calenders.

2.3.1. Hot-Melt Process

2.3.2. Solvent-Based Process

2.4. Prepreg Characterization

- o

- Final prepreg width (mm), measured by digital caliper (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan) along prepreg length.

- o

- Resin Content (%) of the prepreg specimens was determined in accordance with ASTM D3171, Method I, Procedure G [29]. This method involves heating the specimen in a furnace under controlled conditions until the resin matrix is completely removed and the reinforcing fibers remain. The mass of the specimen before and after the burn-off was recorded, allowing for the calculation of resin and fiber percentages. For this purpose, the following equipment was used:

- o

- Muffle furnace capable of reaching 600 °C with accurate temperature control;

- o

- Analytical balance 204, model CPA2245-0CE (Sartorius AD, Göttingen, Germany);

- o

- High-temperature-resistant ceramic crucibles;

- o

- Tweezers and metal tongs for handling heated crucibles

- o

- Volatile Content (%) of the prepreg was determined following ASTM D3530 [30]. Specimens were weighed before and after exposure to elevated temperature in an air-circulating oven to remove solvents, retained moisture, and low molecular weight constituents, and the mass loss was expressed as volatile content percentage.

- o

- Prepreg weight (gsm)—100 mm × 100 mm specimens were cut and weighed on an analytical balance (Analytical balance 204, model CPA2245-0CE, Sartorius AD, Göttingen, Germany).

- o

- Film quality was evaluated visually and by optical microscopy (Carl Zeiss Jena, Jena, Germany) [this was conducted only for the internal in-house purpose—to inspect the film quality and continue with its processing for prepreg].

- o

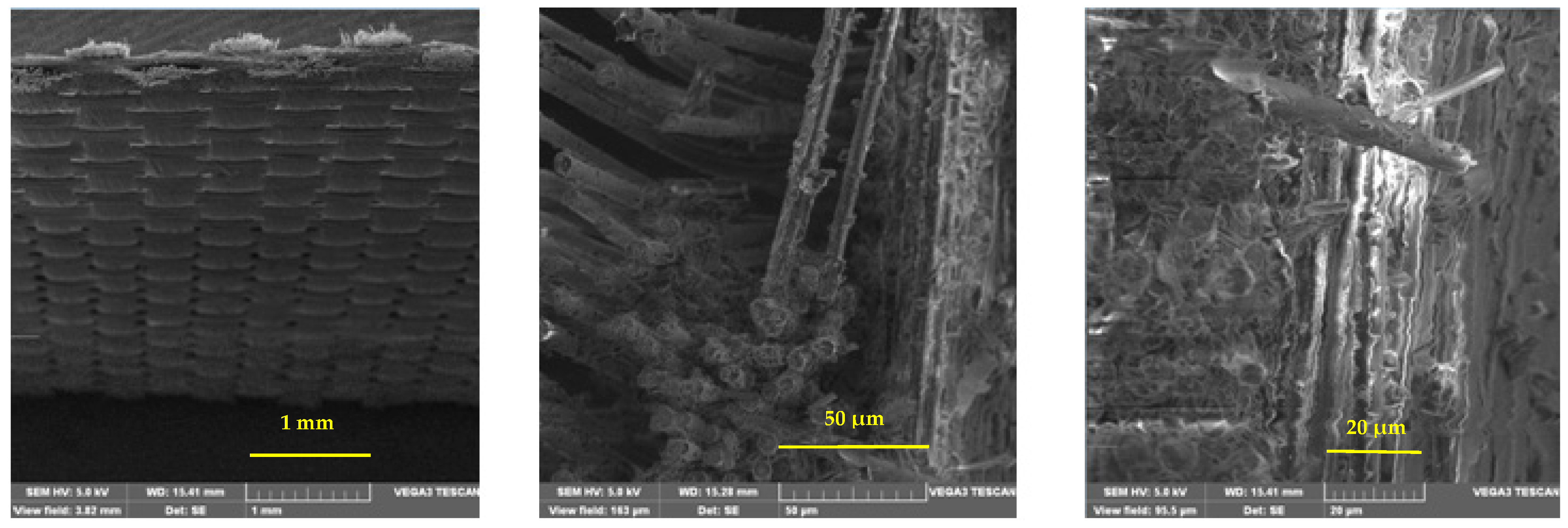

- Representative samples from both hot-melt and solvent impregnation trials were examined by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to observe the resin distribution and fiber–matrix interface. Prior to SEM imaging, the samples were mounted on aluminum stubs using conductive carbon tape and sputter-coated with gold (10 nm) to prevent charging. The images were observed under a magnification of 50× (the scale bars 10–100 µm) and at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. The obtained micrographs illustrate the typical impregnation morphology of PI-based prepregs, and they are used to represent characteristic features such as fiber wetting, resin continuity, and absence of voids, which are consistent with the structural integrity expected for the materials studied.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impregnation with Hot-Melt Technique (UD Prepreg)

- (i)

- The UD prepregs had with a width of ~115 mm and a stable resin content of ~35%. The obtained prepregs had low volatile content (~1.27%) and a uniform prepreg weight (~310 gsm). As shown in Figure 7a, the hot-melt process enabled the formation of a continuous resin film with stable coating without visibly dry spots, although slight resin overflow near the edges was initially observed and corrected by adjusting side guides. The resulting UD prepreg, presented in Figure 7b, confirmed that the applied film provided uniform impregnation of the fiber tows and stable overall quality.

- (ii)

- The hot-melt method can be reproduced with high process stability. The prepregs had a width of close to 120 mm, stable resin content (~35%), low volatiles (~1.27%), and uniform prepreg weight (~308 gsm), Figure 7c (Test II).

- (iii)

- An excellent repeatability of the hot-melt impregnation process was proven. Figure 7d illustrates the UD prepreg (Test IV), showing well-defined edges, consistent width (~120 mm), and uniform resin coverage across the tape, which verifies the repeatability and quality of the hot-melt process.

3.2. Impregnation with Solvent-Based Technique (UD Prepreg)

- o

- UD prepregs with a width of ~120 mm were produced with a resin content of ~34.5%, and volatile content ~0.4%, indicating almost complete solvent removal. The prepregs demonstrated uniform weight (~306 gsm) and good fiber impregnation. As illustrated in Figure 9 (test III, exp. 1), the solvent-based process allowed the resin to penetrate deeply and evenly, resulting in a smooth surface along the prepreg width. No major defects or dry areas were visible, confirming good wetting of UD fibers with the 50:50 PI: DMAC solution.

- o

- The process stability of the solvent method was confirmed. Namely, in test V, Exp.1 (standard paper substrate), the prepregs had similar resin content (~35%) and uniform weights (~307 gsm), while in test V, Exp. 2, where Kapton film was used instead of paper, the prepregs showed improved film quality and reduced surface defects, proving the influence of substrate choice on prepreg uniformity. Figure 10 presents prepreg produced on Kapton film, with a smoother and more uniform resin surface than the one produced on paper. This highlights the substrate’s influence on film quality and defect formation. Visual inspection during and after processing confirmed fewer surface defects and better macroscopic uniformity for Kapton-supported prepregs. Although no microscopic analysis was performed, consistent weight and surface appearance clearly demonstrate the positive effect of the substrate on the prepreg quality.

- o

- Moreover, the study was performed with a different PI: DMAC ratio of 45:55 (test VI, exp. 1), which resulted in a lower resin content (~32%) and correspondingly lower areal weight (~294 gsm). This highlights the sensitivity of the solvent-based process to the resin/solvent ratio, but also confirms its capability for producing thinner, lighter prepregs when required.

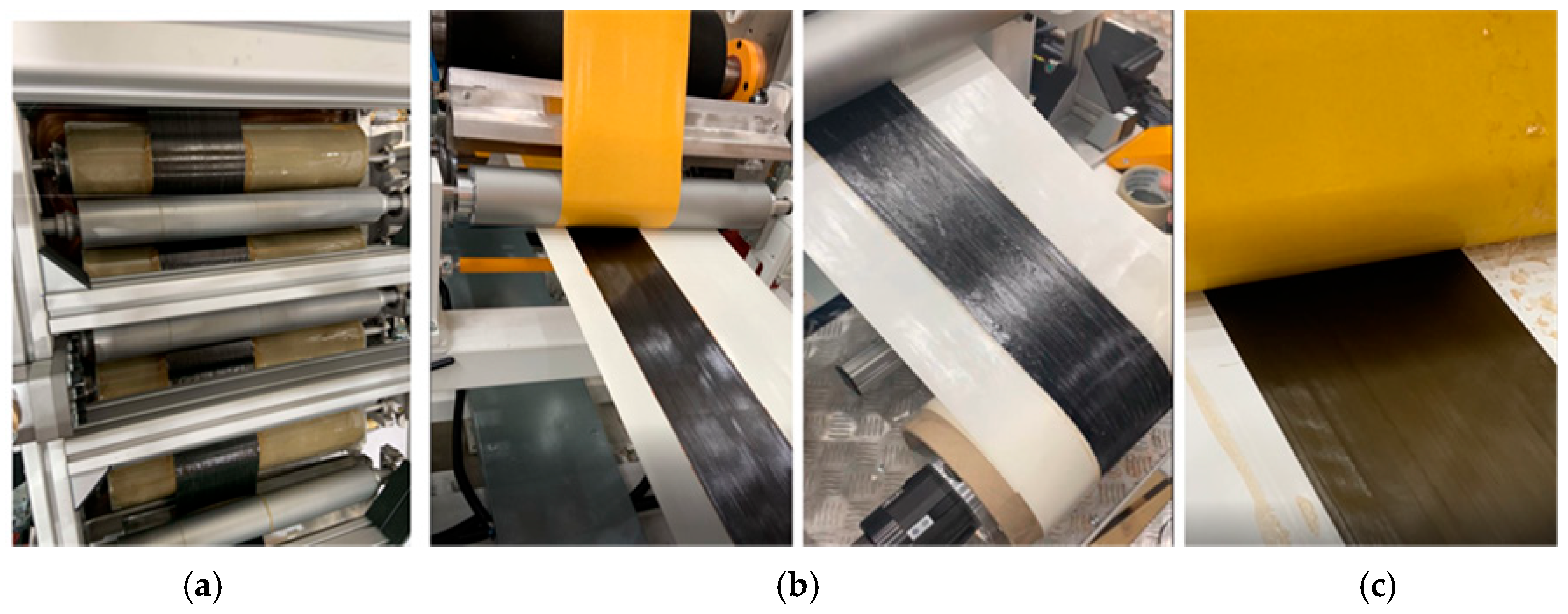

3.3. Impregnation with Solvent Technique (Woven Fabric)

- o

- A fabric prepreg with a width of ~300 mm, resin content of ~37.5%, volatiles ~0.6%, and weight ~320 gsm was produced. The prepreg quality was excellent, with uniform resin distribution across the full width. As shown in Figure 12, the solvent-based process ensures efficient wetting of woven structures.

- o

- When the resin level in the bath was low, it resulted in reduced resin content (~27%) and lower prepreg weight (~270 gsm). These results clearly illustrate the strong dependence of fabric impregnation quality on maintaining the proper resin bath level. As illustrated in Figure 13, insufficient solvent in the bath led to regions with lower resin uptake and visible dry spots across the fabric, emphasizing the critical need for proper bath conditions during solvent-based impregnation.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Used Methods for Prepreg Manufacturing

4. Conclusions, Future Perspectives, and Challenges

- (1)

- The hot-melt impregnation method ensures stable and reproducible resin content, minimal volatiles, and excellent film uniformity. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for manufacturing unidirectional (UD) prepregs used in high-performance structural applications, including Automated Fiber Placement (AFP) and Automated Tape Laying (ATL) [35,36].

- (2)

- The solvent impregnation method allows for deeper and uniform resin penetration, particularly in woven reinforcements, ensuring better impregnation of complex fabric architectures compared to the hot-melt based method. It offers higher adaptability to process variations, although it is more sensitive to resin/solvent ratio as well as bath conditions.

- (3)

- The selection of impregnation method should therefore be guided by reinforcement type and by the end-use application:

- o

- Hot-melt for UD prepregs where precision in resin control is critical. The integrated (in situ) hot-melt setup demonstrated high process stability and reproducibility, confirming its potential for scalable industrial prepreg production.

- o

- Solvent impregnation for woven fabrics, where deep resin wetting and uniformity are essential.

- (i)

- (ii)

- Use of hybrid novel systems in terms of thermoset–thermoplast polymer matrices and/or novel (modified) processes where improved thermal and mechanical properties of final composites are achieved, but also material/energy savings are assumed [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Moreover, future research could explore the use of hybrid materials by implementing nanomaterials in composite materials to customize the mechanical, thermal, barrier, or physico-chemical properties of the final composite material’s properties. These hybrid matrices broaden the potential applications of high-performance composites. For example, in a hybrid system where carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were added, enhanced thermo-mechanical properties were obtained; more specifically, the interlaminar fracture toughness, interlaminar shear strength, and flexural strength, at a loading concentration of only 0.5% CNT addition to CF/PI composite, were improved [43,47]. The nano-inclusions can reinforce/bridge the micro gaps between CF and CF/PI, enhancing stress transfer and inhibiting crack propagation.

- (iii)

- Incorporation of self-healing agents in the form of microcapsules or reversible polymer networks within prepregs that will enable the autonomous repair of microcracks; this will further advance composite materials. In addition, this approach extends service life and reduces the maintenance requirements of composite parts, which is particularly important in aerospace and energy sector applications [48,49].

- (iv)

- (v)

- (vi)

- The use of natural fibers as reinforcements is well-aligned with global sustainability goals; namely, natural fibers such as flax, hemp, or jute are being investigated as alternatives or in hybrid combinations with carbon fibers within prepreg composites [55]. In this context, bio-based polymer matrices are also being investigated for a wide range of structural composites, or at least to replace a part of the fossil-based polymer matrices in the prepreg composition. They offer partially bio-based, cost-effective, and recyclable solutions, while reducing environmental impact [3,55]. Recycling opportunities for novel types of composite materials need to be further explored, considering zero-waste technologies and improved socio-economic aspects [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajak, D.K.; Pagar, D.D.; Menezes, P.L.; Linul, E. Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: Manufacturing, Properties, and Applications. Polymers 2019, 11, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, G.; Vaidya, U.; Wang, H. Past, present and future prospective of global carbon fibre composite developments and applications. Compos. Part B 2023, 250, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, K.; Guler, G.E.; NBilisik, E. Classification of fiber reinforcement architecture. In Advanced Structural Textile Composites Forming; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarathna, Y.; Herath, M.; Epaarachchi, J.; Islam, M.M. Formulation of Epoxy Prepregs, Synthesization Parameters, and Resin Impregnation Approaches—A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovska Petkoska, A.; Samakoski, B.; Samardjioska Azmanoska, B.; Velkovska, V. Towpreg—An Advanced Composite Material with a Potential for Pressurized Hydrogen Storage Vessels. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huo, S.; Chevali, V.; Hall, W.; Offringa, A.; Song, P.; Wang, H. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastics: From Materials to Manufacturing and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, D.S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Devarajan, P.; Stefanska, A.; Wodzynski, Ł.; Koda, E. Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Composites in Civil Engineering Application—A Comprehensive Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, Z.; Liang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Dai, G.; Wei, K.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Alexandrov, I.V. Preparation of continuous carbon fiber reinforced PA6 prepreg filaments with high fiber volume fraction. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 11, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xin, C.; Ren, F.; He, Y. A Novel Slot Die and Impregnation Model for Continuous Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic UD-tape. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2023, 30, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kang, J.; Huh, M.; Yun, S.I. Styrene-free synthesis and curing behavior of vinyl ester resin films for hot-melt prepreg process. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 30, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, L.; Zhu, W. High-content continuous carbon fiber reinforced multifunctional prepreg filaments suitable for direct 3D-printing. Compos. Commun. 2023, 44, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Lv, X.; Wen, X.; Liu, X.; Zhi, J.; Yang, Y.; Cao, L.; Yuan, L. High-content continuous carbon fiber reinforced polyamide prepreg filaments via solution impregnation: Microstructure optimization and enhanced mechanical properties for 3D printing. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 47, 113024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, V. Global Prepreg Market Size, Share, and Trends Analysis Report—Industry Overview and Forecast to 2032. Available online: https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/global-prepreg-market (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ke, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, X. Performance of high-temperature thermosetting polyimide composites modified with thermoplastic polyimide. Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Jing, E.; Qiu, H.; Sun, Z.-Y. Discovering polyimides and their composites with targeted mechanical properties through explainable machine learning. J. Mater. Inf. 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinoska, B.; Risteska, S.; Samakoski, B. Influence of the Process Parameters on Manufactured Prepregs by Solvent Impregnation. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2021, 10, 715–719. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Ji, M. Polyimide Matrices for Carbon Fiber Composites. In Advanced Polyimide Materials; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China; Elsevier, Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Min, Y. Enhanced mechanical and thermal performance of Crosslinked Polyimides: Insights from molecular dynamics simulations and experimental characterization for motor insulation applications. Polym. Test. 2025, 143, 108705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W. 3D printing of heat-resistant thermosetting pol-yimide composite with high dimensional accuracy and mechanical property. Compos. Part B 2025, 298, 112394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Yuan, L.-L.; Hong, W.-J.; Yang, S.-Y. Improved Melt Processabilities of Thermosetting Polyimide Matrix Resins for High Temperature Carbon Fiber Composite Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daghigh, V.; Daghigh, H.; Harrison, R. High-Temperature Polyimide Composites—A Review on Polyimide Types, Manufacturing, and Mechanical and Thermal Behavior. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Khim, S.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, E.; Song, J.; Choi, J.; Yeo, H.; Nam, K.-H. Curing Kinetics of Ultrahigh-Temperature Thermosetting Polyimides Based on Phenylethynyl-Terminated Imide Oligomers with Different Backbone Conformations. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 13401–13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Li, R.; Li, T.; Zi, Y.; Qi, S.; Wu, D. Effects of pre-imidization on rheological behaviors of polyamic acid solution and thermal mechanical properties of polyimide film: An experiment and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 14518–14530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhai, L.; Mo, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.-X.; Du, X.-Y.; He, M.-H.; Fan, L. Effect of Low-temperature Imidization on Properties and Aggregation Structures of Pol-yimide Films with Different Rigidity. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 42, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, B.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Bao, J. Enhanced Interfacial Properties of Carbon Fiber/Polymerization of Monomers Reactants Method Polyimide Composite by Polyimide Sizing. Materials 2024, 17, 5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, O.; Oda, S.; Uzawa, K. Impregnation process of large-tow carbon-fiber woven fabric/polyamide 6 composites using solvent method. Compos. Part A 2024, 180, 108068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, C.; Jay, K.; Petty, C.A. Processing Effects in Production of Composite Prepreg by Hot Melt Impregnation. Polym. Compos. 1993, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmanoska, B.S.; Velkovska, V.; Pizhov, A.; Risteska, S.; Samak, S.; Kostadinoska, B. Determination of parameters for obtaining resin film for production of prepreg by hot-melt procedure. In Proceedings of the 26th Congress of Society of Chemists and Technologists of Macedonia, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 20–23 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D3171:22; Standard Test Methods for Constituent Content of Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D3530-20; Standard Test Method for Volatiles Content of Composite Material Prepreg. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Dhinakaran, V.; Surendar, K.V.; Riyaz, M.S.H. Ravichandran. Review on study of thermosetting and thermoplastic materials in the automated fiber placement process. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budelmann, D.; Schmidt, C.; Meiners, D. Prepreg tack: A review of mechanisms, measurement, and manufacturing implication. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 3440–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Ding, C.Y.; Yousaf, I.; Khan, H.M. E-glass/Phenolic Prepreg Processing by Solvent Impregnation. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2008, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, B.; Ren, F.; Zhu, C.; He, Y.; Xin, C. Isothermal crystallisation ATP process for thermoplastic composites with semi-crystalline matrices using automated tape placement machine. Compos. Part B 2021, 227, 109381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosella, S.; Hügle, S.; Helber, F.; Middendorf, P. A short review on recent advances in automated fiber placement and filament winding technologies. Compos. Part B 2024, 287, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, A.; Sacco, C.; Halbritter, J.; Wehbe, R.; Harik, R. Automated fiber placement: A review of history, current technologies, and future paths forward. Composites Part C Open Access 2021, 6, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Rossitti, I.; Sambucci, M. Different Production Processes for Thermoplastic Composite Materials: Sustainability versus Mechanical Properties and Processes Parameter. Polymers 2023, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohair, B.; Dufresne, S.; Poirier, D.; Turgeon, M.; Elbouazzaoui, S. Hot melt thermoset/thermoplastic hybrid prepregs: Effects of B-stage conditions on the quality of composite parts. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, O.P.L.; Duhovic, M.; Somashekar, A.A.; Bhattacharyya, D. Pre-impregnated natural fibre-thermoplastic composite tape manufacture using a novel process. Compos. Part A 2017, 101, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zhang, C.; Dong, X.; Fu, K.K. Rapid and energy-efficient manufacturing of thermoset prepreg via localized in-plane thermal assist (LITA) technique. Compos. Part A 2022, 161, 107121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Bag, D.S.; Maiti, P. High strength glass fiber / PEEK prepreg using slurry processing for structural application. J. Mater. Sci. Compos. 2025, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tusiime, R.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, H. Enhancing the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Resin via Blending with Thermoplastic Polysulfone. Polymers 2019, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Ou, Y.; Li, J.; Meng, X.; Mao, D. Tailoring thermomechanical performance of carbon fiber/polyimide composites via carbon nanotube interface engineering. Carbon 2025, 244, 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpoganicz, E.; Hübner, F.; Beier, U.; Geistbeck, M.; Korff, M.; Chen, L.; Tang, Y.; Dickhut, T.; Ruckdaschel, H. Effect of prepreg ply thickness and orientation on tensile properties and damage onset in carbon-fiber composites for cryogenic environments. Compos. Struct. 2025, 359, 118996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jathar, A.; Fatema, S.; Farooqui, M.; Iirekar, D.; Ghumare, P. Nanocomposites: A comprehensive review for sustainable innovations. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2025, 43, 1400–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risteska, S.; Trajkovska Petkoska, A.; Samak, S.; Drienovsky, M. Annealing Effects on the Crystallinity of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyetheretherketone and Polyohenylene Laminate Composites Manufactured by Laser Automatic Tape Placement. Mater. Sci. (MEDŽIAGOTYRA) 2020, 26, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, K.; Ling, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, G.; Yang, X. Enhanced longitudinal compressive strength of CFRP composites with interlaminar CNT film prepreg from hot-melt pre-impregnation. Compos. Commun. 2023, 37, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Baek, J.M.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, J.; Keum, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.Y. Self-healing carbon fiber/epoxy laminates with particulate interlayers of a low-melting-point alloy. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 286, 111792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lim, T.-W.; Sottos, N.R.; White, S.R. Manufacture of carbon-fiber prepreg with thermoplastic/epoxy resin blends and microencapsulated solvent healing agents. Compos. Part A 2019, 121, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Sun, X.; Tretiak, I.; Valverde, M.A.; Kratz, J. Automatic process control of an automated fibre placement machine. Compos. Part A 2023, 168, 107465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, J.; Walczyk, D. In situ impregnation of continuous thermoplastic composite prepreg for additive manufacturing and automated fiber placement. Compos. Part A 2021, 147, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, S.I.; Lim, Y.-I.; Hahn, M.-H.; Jung, J. Prediction of degree of impregnation in thermoplastic unidirectional carbon fiber prepreg by multi-scale computational fluid dynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 185, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.M.; Huelskamp, S.R.; Tanner, C.; Rapking, D.; Ricchi, R.D. Application of tailored fiber placement to fabricate automotive composite components with complex geometries. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risteska, S.; Samak, S.; Samak, V. The Factors That Affect the Expansion of the Tape for It to Avoid Side Effects in the Production of Composites in Online LATP Technology. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S.; Islam, M.R.; Uddin, M.A.; Afroj, S.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Karim, N. Sustainable Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2022, 6, 2200258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, T.; Ikematsu, H.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, N.; Ijuin, N.; Kawada, H.; Arao, Y.; Kubouchi, M. Recovery of carbon fiber from prepreg using nitric acid and evaluation of recycled CFRP. Compos. Part B 2022, 231, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teltschik, J.; Matter, J.; Woebbeking, S.; Jahn, K.; Adasme, Y.B.; Paepegem, W.V.; Drechslera, K.; Tallawi, M. Review on recycling of carbon fibre reinforced thermoplastics with a focus on polyetheretherketone. Compos. Part A 2024, 184, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Kabir, S.F.; Fini, E.H. State of the art in recycling waste thermoplastics and thermosets and their applications in construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, N.; Marques, S.S.L.; Sebbe, N.P.V.; Gerritse, A.; Bernardi, H.H.; Menezes, W.M.M.; da Silva, F.J.G.; Matsushima, J.T.; Giovanetti, L.; Sales-Contini, R.D.C.M. Advancing Sustainability in Aerospace: Evaluating the Performance of Recycled Carbon Fibre Composites in Aircraft Wing Spar Design. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, P.R.; Hmeidat, N.S.; Zheng, B.; Penumadu, D. Toward a circular economy: Zero-waste manufacturing of carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites. Npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, K.; Gnanasagaran, C.L.; Vekariya, A. Life cycle assessment of carbon fiber and bio-fiber composites prepared via vacuum bagging technique. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 89, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, R.K.; Singh, R.K.; Purohit, R.; Sinha, P. Natural fibre reinforced composite materials: Environmentally better life cycle assessment—A case study. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 3157–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiantzi, C.; Tserpes, K. A Comparative Environmental and Economic Analysis of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Recycling Processes Using Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Method | Reinforcement | Experimental Run/Details | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | hot-melt | UD fibers | Exp. 1–2: film production; Exp. 3: UD prepreg | First application of hot-melt process |

| II | hot-melt | UD fibers | Exp.1–2: UD prepreg | Confirmation of process reproducibility |

| IV | hot-melt | UD fibers | Exp.1: UD prepreg | Repeatability test |

| III | solvent-based | UD fibers | Exp.1: UD prepreg (PI:DMAC 50:50) | Process with standard paper substrate |

| V | solvent-based | UD fibers | Exp.1: UD prepreg (paper) Exp.1: UD prepreg (Kapton film) | Comparison of substrates (paper vs. Kapton-polymer) |

| VI | solvent-based | UD fibers | Exp.1: UD prepreg (PI:DMAC 45:65) | Comparison of changing resin/solvent ratio |

| VII | solvent-based | woven fabric | Exp.1: fabric prepreg with sufficient resin bath. Exp.2: fabric prepreg with low resin solution bath | Comparison of resin bath level on prepreg quality |

| Input Parameters | I Tests | II Tests | IV Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | Exp. 3 | Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | |

| Notes | Film producing | Film producing | UD prepreg | UD prepreg | UD prepreg | UD prepreg | UD prepreg |

| Number of fibers | / | / | 29 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Unwinder tension paper [N] | 45 N 1.5 N/cm | 60 N 2 N/cm | 36 N 1.2 N/cm | 45 N 1.5 N/cm | 45 N 1.5 N/cm | 36 N 1.2 N/cm | 45 N 1.5 N/cm |

| Rewinder tension—prepreg/paper [N] | 60 N 2 N/cm | 60 N 2 N/cm | 135 N 4.5 N/cm | 150 N 5 N/cm | 150 N 5 N/cm | 150 N 5 N/cm | 150 N 5 N/cm |

| Tension fibers (N) | / | / | 87 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) |

| S1/S2 gap [mm] | 0.15 (0.1) | 0.15 (0.1) | 0.15 (0.1) | 0.185 (0.15) | 0.185 (0.15) | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| S1/S2 speed ratio | 1:0.1 | 1.5:0.0 | 1.5:0.15 | 1.5:0.1 | 1.5:0.1 | 1.5:0.1 | 1.5:0.1 |

| S1/M speed ratio | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Pressure M [bar] | 4 bar | 4 bar | 4 bar | 4 bar | 4 bar | 4 bar | 4 bar |

| Coating Unit and Callender 1 [°C] | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| Film width [mm] | 115 mm | 115 mm | 115 mm | 120 mm | 120 mm | 120 mm | 120 mm |

| Oven 1/Calender Unit 2 [°C] | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Oven 2/Calender Unit 3 [°C] | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Ventilation flow rate Oven 2 [m3/h] | 600 | 650 | 650 | 650 | 650 | 800 | 900 |

| Gap adjustment at Calender Unit 1 [mm] | / | / | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Gap adjustment at Calender Unit 2 [mm] | / | / | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Gap adjustment at Calender Unit 3 [mm] | / | / | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Gap adjustment at Master-Nip roller/Pulling Unit 4 | / | / | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Gap adjustment at Lamination Unit [mm] | / | / | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Line speed | 1 m/min | 1–1.5 m/min | 1.5 m/min | 1.5 m/min | 1.5 m/min | 1.5/2 | 3 |

| Paper type/width | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm |

| Input Parameters | III Tests | V Tests | VI Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | Exp. 1 | |

| Number of fibers | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Unwinder tension paper [N] | 45 N 1.5 N/cm | 36 N 1.2 N/cm | 45 N 1.5 N/cm | 30 N 1 N/cm |

| Rewinder tension—prepreg/paper [N] | 130 N 4.5 N/cm | 120 N 4 N/cm | 135 N 4.5 N/cm | 120 N 4 N/cm |

| Tension fibers (N) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) | 90 N (3 N per fiber) |

| Resin bath temperature [°C] | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Oven 1/Calender Unit 2 [°C] | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Oven 2/Calender Unit 3 [°C] | 150 | 120 | 120 | 150 |

| Ventilation flow rate Oven 1,2 [m3/h] | 700 | 800 | 900 | 800 |

| Calender Unit 1 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Calender Unit 2 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Calender Unit 3 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| Master-Nip roller/Pulling Unit 4 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| Lamination Unit gap adjustment [mm] | 0.4 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.4 |

| Line speed [m/min] | 1/2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Resin system (PI:DMAC) | 50:50 | 50:50 | 50:50 | 45:55 |

| Kapton Film/width | / | / | 92 g/m2/30 cm | / |

| Paper type/width | 92 g/m2/30 cm | 92 g/m2/30 cm | / | 92 g/m2/30 cm |

| Input Parameters | VII Tests | |

|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 (Low Resin Level in Bath) | |

| Carbon fabric width [mm] | 30 | 30 |

| Unwinder tension fabric [N] | 90 N 3 N/cm | 90 N 3 N/cm |

| Unwinder tension film [N] | 31 N 0.9 N/cm | 35 N 1 N/cm |

| Rewinder tension—prepreg/paper [N] | 135 N 4.5 N/cm | 150 N 5 N/cm |

| Resin bath temperature [°C] | 40 | 40 |

| Oven 1/Calender Unit 2 [°C] | 100 | 100 |

| Oven 2/Calender Unit 3 [°C] | 120 | 150 |

| Ventilation flow rate Oven 2 [m3/h] | 900 | 850 |

| Calender Unit 1 gap adjustment [mm] | / | / |

| Calender Unit 2 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Calender Unit 3 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Master-Nip roller/Pulling Unit 4 gap adjustment [mm] | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Lamination Unit gap adjustment [mm] | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Line speed [m/min] | 3 | 2.5 |

| Carbon fabric/width | 200 g/m2/30 cm | 200 g/m2/30 cm |

| Kapton Film/width | 50 g/m2/35 cm | 50 g/m2/35 cm |

| Polyethylene Film/width | 50 g/m2/35 cm | 50 g/m2/35 cm |

| Paper type/width | 92 g/m2/35 cm | 92 g/m2/35 cm |

| Test I Exp. 3 | Test II Exp. 1 | Test IV Exp. 1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Average |

| Width (mm) | 114.9 | 115.2 | 115.1 | 115.1 | 119.7 | 120.2 | 120.3 | 120.1 | 119.8 | 120.3 | 120.1 | 120.1 |

| Volatile [%] | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.27 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.27 | 2.1 | 1.35 | 1 | 1.47 |

| Resin [%] | 34.7 | 35.1 | 35.0 | 34.98 | 34.6 | 35.3 | 35.0 | 34.97 | 34.6 | 35.3 | 35.1 | 35.0 |

| UD prepreg [gsm] | 309 | 311 | 310.5 | 310.2 | 306.0 | 309.0 | 307.5 | 307.5 | 306.0 | 309.0 | 308.0 | 307.8 |

| Test III | Test V | Test VI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp 1 | Exp 1 | Exp 2 | Exp 1 | |||||||||

| Parameter | Sample 1 | Sample 1 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 1 | Average |

| Width (mm) | 119.3 | 119.5 | 119.4 | 119.7 | 119.6 | 119.7 | 119.9 | 120.1 | 120.0 | 119.5 | 120.2 | 119.9 |

| Volatile [%] | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.35 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.45 |

| Resin [%] | 34.5 | 34.6 | 34.5 | 34.7 | 35.0 | 34.9 | 35.2 | 34.6 | 34.9 | 31.8 | 32.2 | 32.0 |

| UD prepreg [gsm] | 305.5 | 306 | 305.8 | 306.5 | 307.5 | 307 | 308.5 | 306 | 307.3 | 293.5 | 295.0 | 294.3 |

| Test VII | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | |||||||

| Parameter | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Average | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Average |

| Width (mm) | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 | 300.0 |

| Volatile [%] | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.63 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Resin [%] | 37.3 | 38 | 37 | 37.43 | 27.9 | 25 | 27 | 26.63 |

| UD prepreg [gsm] | 318.8 | 322.6 | 317.5 | 319.63 | 274.5 | 265 | 270 | 269.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostadinoska, B.; Samakoski, B.; Samak, S.; Cvetkoska, D.; Trajkovska Petkoska, A. Comparative Analysis of Impregnation Methods for Polyimide-Based Prepregs: Insights from Industrial Perspective. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120651

Kostadinoska B, Samakoski B, Samak S, Cvetkoska D, Trajkovska Petkoska A. Comparative Analysis of Impregnation Methods for Polyimide-Based Prepregs: Insights from Industrial Perspective. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):651. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120651

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostadinoska, Biljana, Blagoja Samakoski, Samoil Samak, Dijana Cvetkoska, and Anka Trajkovska Petkoska. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Impregnation Methods for Polyimide-Based Prepregs: Insights from Industrial Perspective" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120651

APA StyleKostadinoska, B., Samakoski, B., Samak, S., Cvetkoska, D., & Trajkovska Petkoska, A. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Impregnation Methods for Polyimide-Based Prepregs: Insights from Industrial Perspective. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120651