1. Introduction

In recent years, small vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) have attracted considerable attention due to their versatility [

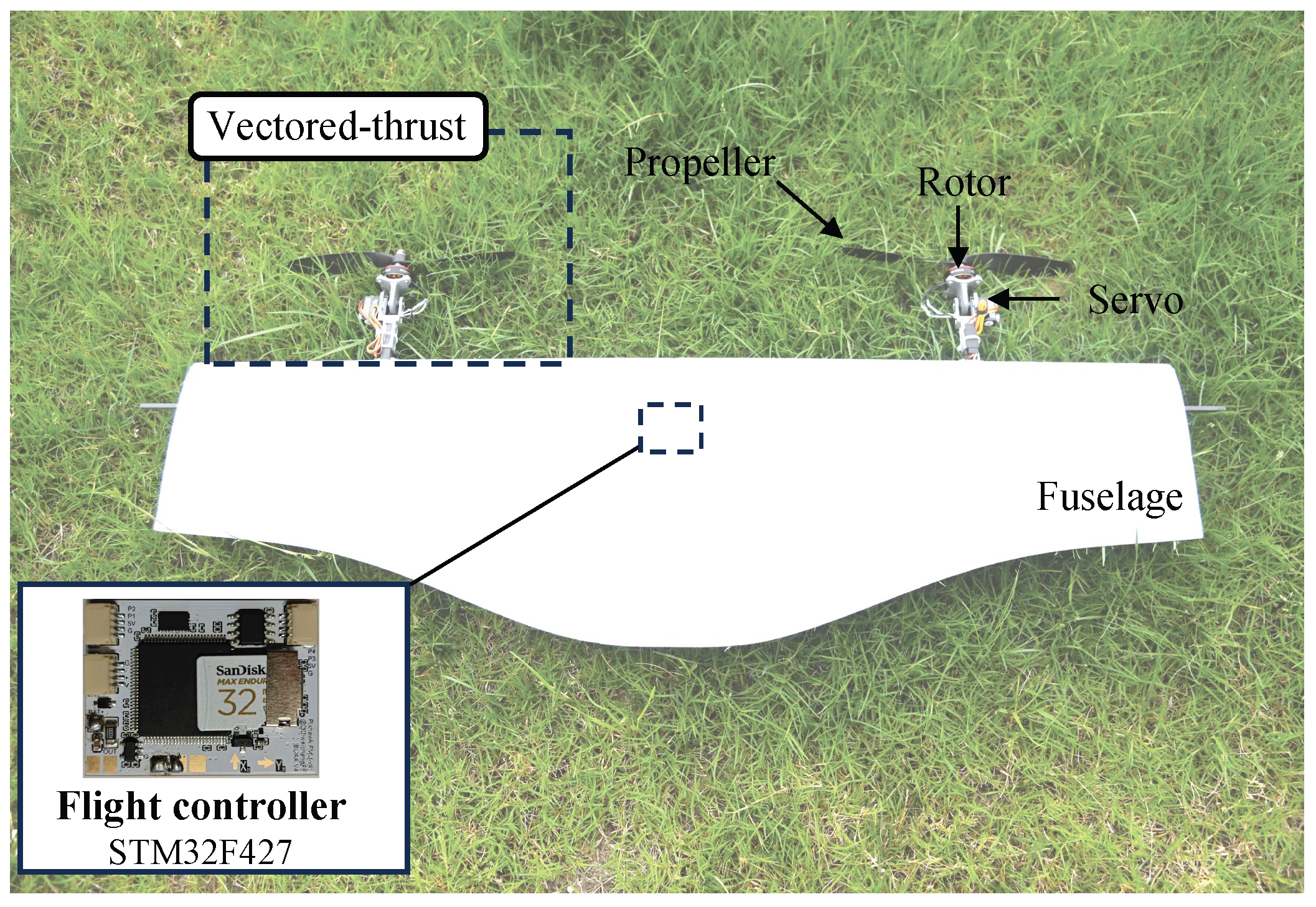

1]. Configurations like helicopter and compound rotorcraft suffer from poor forward flight performance, while the complex design of tilt-rotor wings makes them difficult to integrate into compact UAV platforms. Vectored-thrust, where the propulsion can be actively deflected to generate multi-axis control torques, enables high maneuverability. This enables rapid switching between flight modes and performing complex maneuvers that are not possible with fixed-wing aircraft. Furthermore, the tailless flying wing layout further reduces structural weight, reduces fuselage size, and improves aerodynamic efficiency, enabling the inclusion of more equipment and achieving superior forward flight performance. These characteristics reduce reliance on the take-off/landing environment, which offers potential for air combat, surveillance, and rescue missions [

2]. However, the small tailless VTOL UAV (ST-VTOL UAV) faces stability challenges during take-off and landing. Although tailless vectored thrust configurations offer excellent maneuverability, they also increase the complexity of controller design. Therefore, it is necessary to design a controller that addresses the effects of wind disturbance.

Existing research has focused mainly on two directions to enhance the wind-disturbance rejection capability of small UAVs: perception-based methods and observer-based methods. Perception-based methods rely on additional airflow sensors to directly measure the surrounding wind field and feed the obtained information to the controller as a feedforward signal [

3,

4]. For example, a thermistor-based airflow sensing method was proposed, in which real-time wind speed measurements were combined with feedforward compensation, effectively improving the flight stability of small UAVs within a wind speed range of 0.5–1.2 m/s [

5]. More recently, a skin-like airflow odometry framework was introduced for small UAVs, in which distributed thermal anemometers embedded in wingtips were fused with inertial data through a transformer-enhanced gated recurrent unit (GRU) network, thereby mitigating drift and improving state estimation accuracy under complex airflow conditions [

6]. Nevertheless, such methods depend strongly on sensor accuracy and response speed. At the same time, their additional weight, power consumption, and integration complexity bring challenges for practical deployment on small UAV platforms.

In contrast, observer-based methods avoid direct wind sensing by treating the external wind field as an unknown disturbance, which is estimated and compensated through observers [

7,

8,

9]. Representative approaches include the extended state observer (ESO) [

10], the nonlinear disturbance observer (NDO) [

11], and the unknown input observer (UIO) [

12]. These frameworks can estimate and compensate for disturbances based solely on system input–output data, eliminating the need for airflow sensors. For example, a robust flight controller based on linear active disturbance rejection control was proposed to guarantee quadrotor stability under gusty conditions [

13], and a disturbance rejection control scheme using multiple observers was designed to maintain stable flight under simultaneous wind and load-swing disturbances [

14]. Such methods are attractive for small UAVs, although their effectiveness depends on the richness and observability of feedback signals.

Building upon disturbance estimation, researchers have further investigated how such information can be integrated into control laws. Classical proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control [

15,

16,

17] is simple and widely adopted, but it performs poorly under strong nonlinearities and large disturbances. Model predictive control (MPC) [

18,

19] can explicitly handle constraints but incurs high computational cost; incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion (INDI) [

20,

21] improves adaptability under rapidly changing conditions; and intelligent control approaches [

22,

23] show promising adaptability but rely heavily on training data and computational resources. Sliding mode control (SMC) is widely applied due to its inherent robustness against uncertainties [

24,

25], yet the need for large switching gains often induces actuator chattering. To alleviate this issue, advanced variants such as non-singular terminal SMC and finite-time backstepping SMC have been proposed [

26], while an adaptive fractional-order non-singular terminal SMC with a fixed-time disturbance observer has been demonstrated to significantly improve robustness for carrier-based UAVs with complex layouts under random disturbances [

27].

Recent trends increasingly emphasize the combination of observer-based estimation with robust control to form dual-loop frameworks. The outer loop employs SMC to ensure global robustness, while the inner loop observer provides fast disturbance compensation [

28]. Typical examples include ADRC frameworks based on ESO [

29] and high-order ESOs with improved reaching laws [

30]. However, ESO-based methods are limited by their reliance on single-channel output information, underutilization of structural dynamics, and reduced effectiveness when compensating for unknown nonlinearities [

31]. In addition to ESO-based designs, several finite-time, fixed-time, and prescribed-time observers (FTO/FXTO/PTO) have been developed to achieve convergence within bounded or preassigned time intervals. FTO ensures rapid convergence but depends on initial conditions and often requires high observer gains [

32]. FXTO removes the dependence on initial conditions by introducing homogeneous feedback with time-invariant settling times [

33]. PTO further guarantees convergence within a user-defined duration through nonlinear or time-varying high-gain mechanisms [

34,

35]. However, these designs typically rely on strong homogeneity or nonlinear damping structures, which increase implementation complexity and amplify sensor noise in practice, especially for small UAVs subject to measurement disturbances.

To overcome these limitations, a disturbance rejection framework combining the state compensation function observer (SCFO) with an equivalent SMC (ESMC) has been introduced [

10]. We call this framework SSMC. Unlike ESO- or high-gain-based designs, the SCFO maintains a linear-in-error structure while embedding model Jacobians and a dynamic compensation term to explicitly estimate the disturbance variation rate. This model-aware yet bandwidth-efficient formulation enables rapid disturbance reconstruction and smooth control action without the excessive gain tuning or noise amplification typical of nonlinear homogeneous observers. By incorporating disturbance derivative estimation and smooth switching mechanisms, the SSMC framework significantly improves the trajectory-tracking accuracy of small UAVs under wind disturbances, offering a practically robust solution for flight control in complex and uncertain environments.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in robust disturbance-aware control of UAVs, further research is needed to evaluate the performance of these approaches on novel platforms requiring high wind resistance, such as ST-VTOL UAVs. This study demonstrates the integration of SSMC on an ST-VTOL UAV. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

The SSMC framework introduces an SCFO that embeds system-derivative and Jacobian information directly into the observer dynamics. This design enables faster and smoother disturbance reconstruction than classical ESO-based methods, while avoiding high-gain amplification and preserving robustness for small tailless VTOL UAVs with strong aerodynamic coupling.

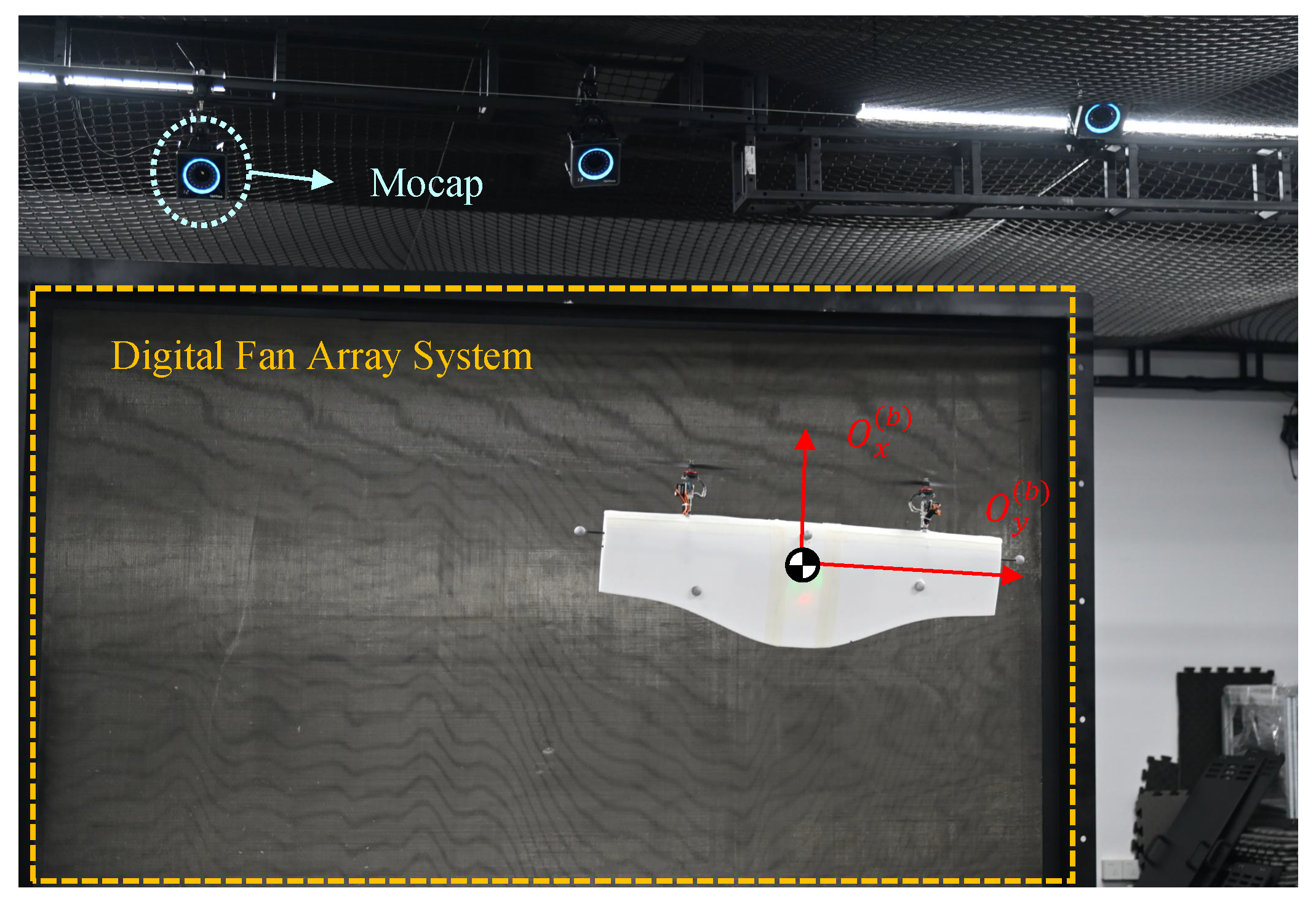

A programmable experimental platform was developed by integrating a reconfigurable fan-array wind generator (FAWG) with a motion-capture-based indoor testbed and a lightweight ST-VTOL prototype. This setup enables repeatable generation of spatial–temporal wind disturbances and provides a refined methodology for validating disturbance-aware controllers on miniature VTOL systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the dynamic modeling of the ST-VTOL UAV used in this paper.

Section 3 introduces the proposed control framework.

Section 4 provides both simulation and experimental results to demonstrate the feasibility of SSMC on ST-VTOL UAV. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Dynamics Modeling

This section introduces the coordinate systems and establishes the six degrees of freedom (6-DOF) equations of motion for the ST-VTOL UAV. The equations are then simplified to a longitudinal three degrees of freedom (3-DOF) form, incorporating wind disturbances.

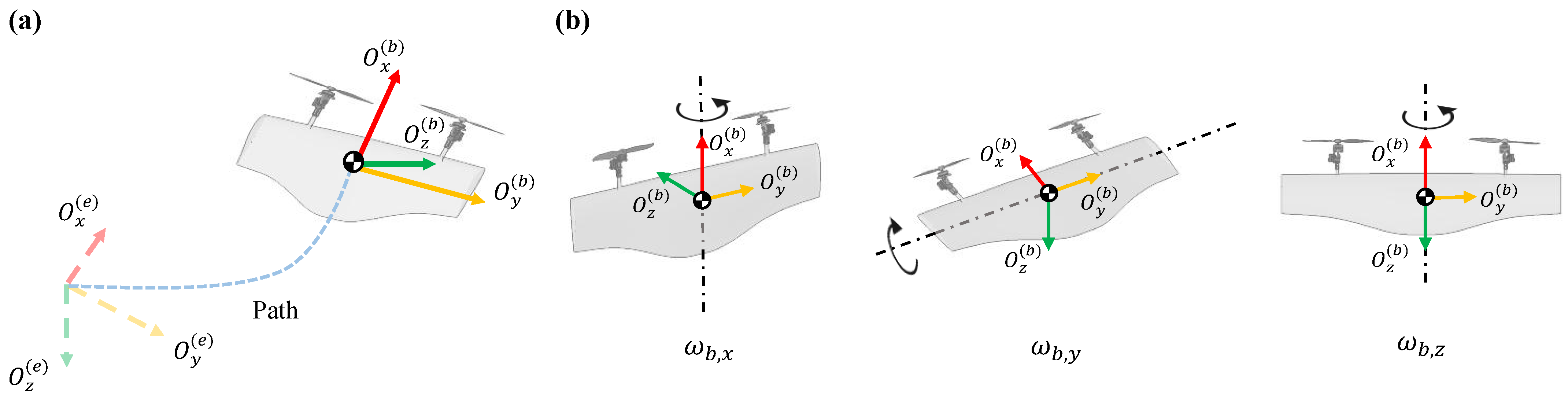

The definition of the coordinate system can be seen in

Figure 1a. The inertial frame

is fixed at the takeoff point and aligned with the North-East-Down (NED) directions. The body-fixed frame

is attached to the ST-VTOL UAV’s center of gravity, with

pointing forward,

pointing downward, and

completing the right-hand rule, as illustrated in

Figure 1b. The rotation matrix from the body frame to the inertial frame

[

36] is:

where

,

, and

denote the Euler angles corresponding to roll, pitch, and yaw, respectively. Specifically,

is the angle between the UAV’s symmetry plane and the vertical plane containing the body axis

, and it is defined as positive when the UAV rolls to the right.

is the angle between the body axis

and the horizontal plane

–

, defined as positive when the UAV pitches nose-up.

is the angle between the projection of the body axis

onto the horizontal plane

–

and the inertial axis

, defined as positive when the UAV yaws to the right.

Additionally, the aerodynamic frame

is defined along the direction of the relative airflow, where

points opposite to the incoming airflow (aligned with the flight velocity vector),

is perpendicular to

and points upward in the lift direction, and

completes the right-hand coordinate system. The rotation matrix from the aerodynamic frame to the body frame

is:

where

and

denote the angle of attack and sideslip angle, respectively. Specifically,

is defined as the angle between the projection of the velocity vector on the UAV’s symmetry plane and the body axis

, and it is defined as positive when the projection lies above the

-axis.

is defined as the angle between the velocity vector and the UAV’s symmetry plane, and it is defined as positive when the velocity vector lies on the right-hand side of the symmetry plane.

These coordinate systems form the foundation for expressing the aerodynamic and propulsive forces acting on the ST-VTOL UAV.

In order to describe the relationship between the forces and moments acting on an ST-VTOL UAV and its flight state, the motion can be fully characterized by a 6-DOF equation, including three translational motions in the inertial frame and three rotational motions about the body axes. The dynamic equations can be derived from the Newton–Euler equations [

36]:

where

m is the mass of the ST-VTOL UAV,

is the velocity vector in the inertial frame,

g is the gravitational acceleration,

is the unit vector of gravity in the inertial frame,

is the external force acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame,

is the inertia matrix where

,

, and

are the principal moments of inertia about the

,

, and

axes, respectively,

is the angular velocity in the body frame, and

is the external moment acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame.

There exists a linear relationship between the body angular velocity

and the time derivatives of the Euler angles [

37]:

The forces acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame mainly include the aerodynamic force

and the thrust force

, while the moments mainly consist of the aerodynamic moment

and the thrust moment

, which are expressed as follows:

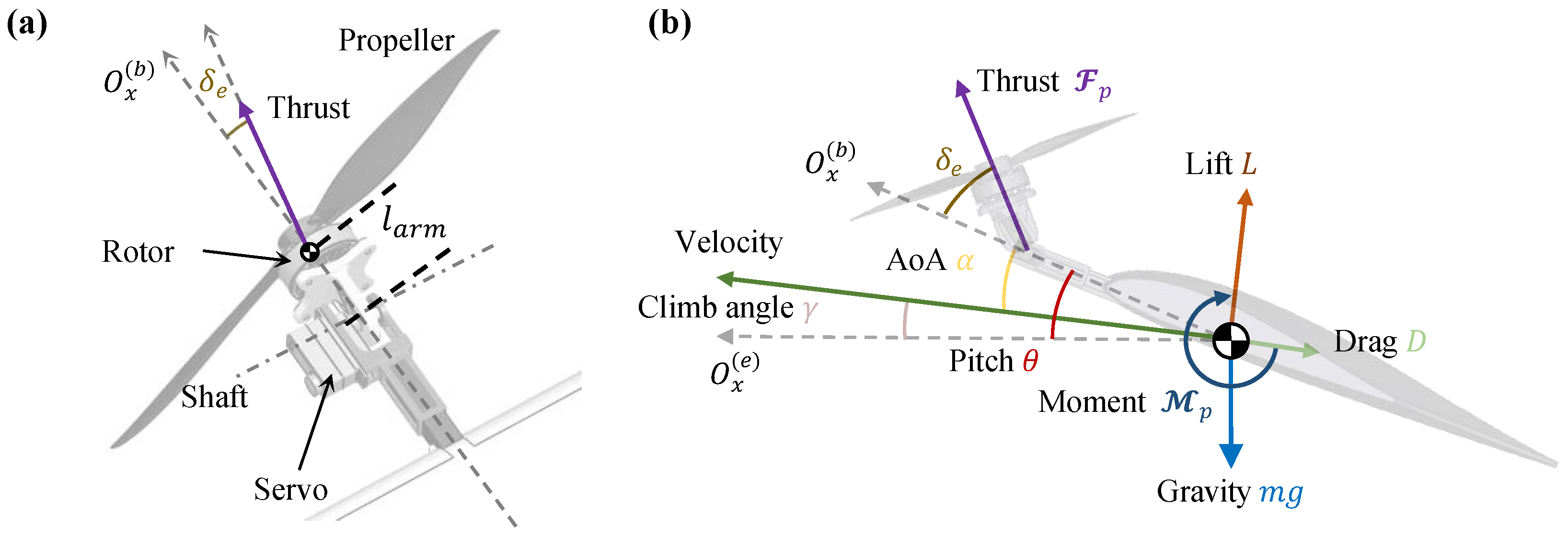

2.1. Thrust and Thrust Moment Calculation

The ST-VTOL UAV consists of two servos and a motor propeller, which form a vector propulsion unit through a linkage mechanism to provide thrust and thrust moment, as illustrated in

Figure 2a,b. Taking the left propeller as an example, the magnitudes of the thrust

and torque

are calculated as:

where

and

respectively denote the thrust and torque coefficients of the propeller, which are obtained from CFD analysis [

38].

is the air density,

n is the propeller rotational speed with the unit of revolutions per second (rps), and

is the propeller diameter.

When the propellers on both sides accelerate synchronously, the ST-VTOL UAV gains thrust for acceleration or climbing. Differential propeller speeds generate a yawing moment , while identical servo deflections produce a pitching moment . Conversely, opposite servo deflections induce a rolling moment . By vector summation of these components, the resultant thrust and thrust moment acting on the ST-VTOL UAV are obtained.

It should be noted that we define the angle between the thrust direction of the propeller and

as the vectored thrust deflection angle

, which is shown in

Figure 2. The direction of the propeller thrust is related to the attitude and the

.

governs the decomposition of thrust into horizontal and vertical components and generates an additional pitching moment depending on the arm length

between the thrust axis and the center of gravity. In addition, we define the throttle command as

, which represents the percentage of the maximum available thrust.

2.2. Aerodynamic Force and Aerodynamic Moment Calculations

The aerodynamic model used in this paper is defined as follows [

39]:

where

is the airspeed of the ST-VTOL UAV, given by

, and

is the wind velocity expressed in the inertial frame.

is the dynamic pressure,

S is the wing reference area, and

is the mean aerodynamic chord.

,

, and

represent the lift, side force, and drag coefficients, respectively. The calculated values of

L,

Y, and

D correspond to the three components of

along the aerodynamic frame

. The aerodynamic force can then be obtained through

.

,

, and

represent the rolling, pitching, and yawing moment coefficients, corresponding to the aerodynamic moments

,

, and

about the three body axes. These components together constitute the aerodynamic moment vector

in the body frame.

During the rotational motion of the ST-VTOL UAV, aerodynamic damping moments are generated, and the coupling between aerodynamic forces and rotational motion becomes significant. The open-source tool AVL can be utilized to compute the dynamic stability derivatives, such as . The nondimensional angular velocity is defined as .

Taking the pitching moment coefficient

as an example, it can be expressed as:

where

is the static pitching moment coefficient, which can be obtained from wind tunnel experiments [

38]. The superscript

denotes the components related to thrust effects. Other aerodynamic moment coefficients are defined in a similar manner.

2.3. Dynamics Simplification

In this paper, we focus primarily on the take-off and landing phases under wind disturbances. Inspired by the study in [

40], the wind resistance of VTOL fixed-wing UAVs and similar platforms reaches its optimum when the wind direction is aligned with the heading direction. Due to the configuration characteristics, the main stability challenge introduced by the fixed wings lies in the longitudinal symmetric plane. Moreover, wind tunnel experiments have demonstrated that the ST-VTOL UAV exhibits lateral-directional stability [

38]. Therefore, to achieve the theoretically optimal wind-resistance performance while reducing the complexity of controller design, the anti-disturbance control strategy adopted in this paper is mainly developed for the longitudinal dynamics.

Therefore, the 6-DOF dynamics in Equation (

3) can be reduced to a 3-DOF model in the longitudinal plane. After simplification, in Equation (

3), the translational equations retain only the terms related to

and

, while the rotational equation retains only the terms associated with the pitch angle

.

By combining aerodynamic forces, propeller thrust, and gravity, and further incorporating wind-induced uncertainties, the longitudinal 3-DOF dynamics of the ST-VTOL UAV are formulated as:

where

is the pitch-axis moment of inertia,

is the flight path angle. The additive terms

and

represent the equivalent wind-induced disturbances on vertical and pitch accelerations.

2.4. Wind Disturbance Model Establishment

To make the wind field model more closely resemble the real environment, the designed wind field model requires a high wind speed and variable direction within the wind field. Strong winds and turbulent winds are superimposed to create a turbulent wind field with high wind speeds and uncertain wind directions. The wind field model is incorporated as an interference term into the dynamic model of the ST-VTOL UAV, and the controller is designed to compensate for this interference term, thereby achieving the goal of resisting wind disturbances.

The Dryden model is used to describe the turbulent wind field. A Gaussian-distributed random signal is generated by a computer. To output a suitable turbulent signal, the spatial and temporal spectra of the model are decomposed to obtain the shaping filter transfer functions in each direction. The white noise is then passed through the shaping filter to obtain the output of the turbulent wind field model, which is more closely aligned with the actual wind field. Atmospheric disturbances encompass a range of temporal and spatial scale motions, and their generation mechanisms and development processes differ. The Dryden atmospheric turbulence model passes a standard Gaussian white noise sequence through a shaping filter to form a colored noise sequence, completing the simulation of atmospheric turbulence [

41]. The time spectrum function of the Dryden model is:

where

denotes the temporal frequency,

,

, and

are the turbulence scale lengths, and

,

, and

are the turbulence intensities. The components

u,

v, and

w represent the velocity vector along

.

Since the flight altitude of the ST-VTOL UAV is limited, the turbulence intensity and turbulence scale under low-altitude conditions can be calculated as follows:

where

h denotes the flight altitude, and

represents the wind speed at a height of 6.096 m.

Decompose and simplify Equation (

10) into first order, then the fixed frequency filter is:

In the subsequent simulations, the disturbances and will be generated based on the Dryden model.

In summary, the longitudinal model (

9) explicitly incorporates aerodynamic, propulsive, and gravitational effects while representing wind disturbances through the additive terms

and

. This formulation provides a tractable yet sufficiently accurate foundation for subsequent controller design, where disturbances will be estimated and compensated in real-time.

3. Controller Design

Building on the dynamic model in

Section 2, this section first presents the overall control architecture, then details lateral PID, horizontal position shaping, and a longitudinal ESMC enhanced by an SCFO.

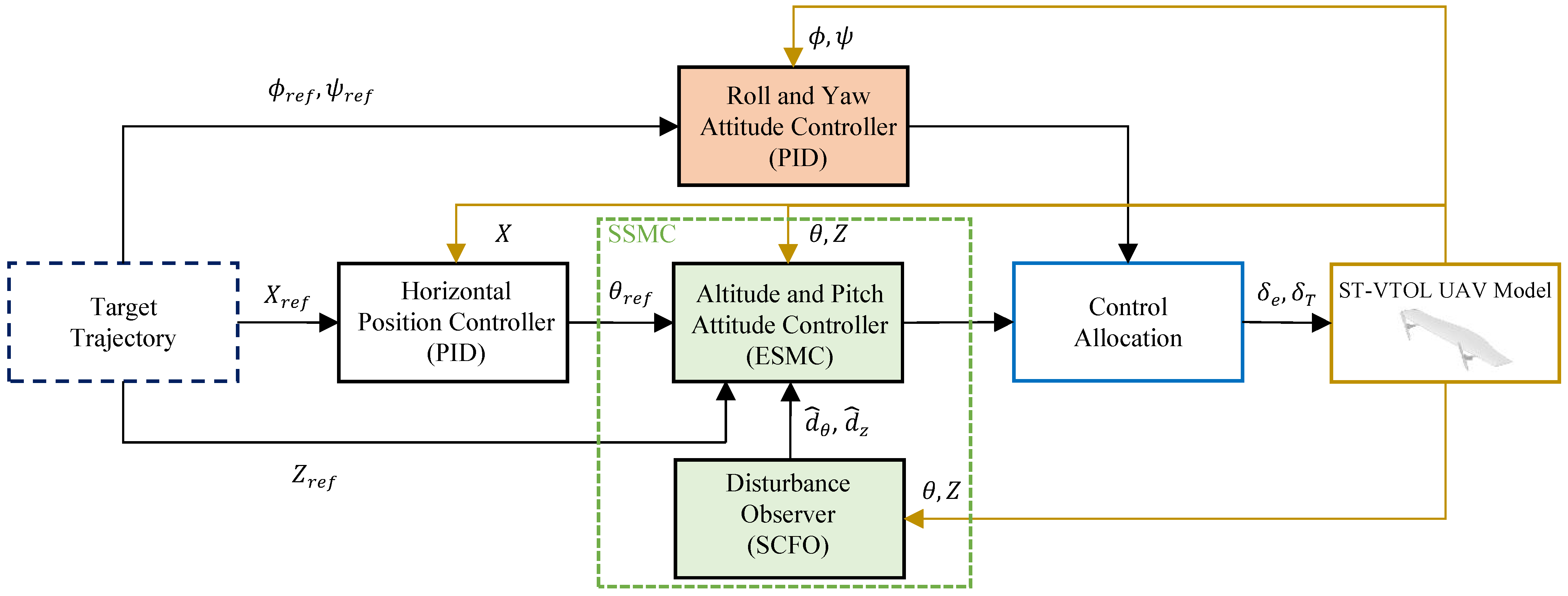

To achieve precise hovering under external wind disturbances, we use the new anti-disturbance control method—SSMC.

Figure 3 shows its overall control structure. The position and attitude controllers are designed using a cascaded state feedback strategy. Specifically, the lateral control goal is to keep the roll and yaw angles of the ST-VTOL UAV at zero degrees, which a traditional PID controller achieves. For simplicity of notation, in the remainder of this section,

X and

Z refer to the corresponding variables

and

. The longitudinal control objective is to stabilize the ST-VTOL UAV at the reference position

. First, the horizontal position controller uses a PID method to generate the desired pitch angle

. Simultaneously, the desired altitude

is also input into the ESMC and the desired pitch angle. Then, the ESMC tracks

and

concurrently. Finally, the outputs of the lateral and longitudinal controllers are mapped through the control allocation module. This module is responsible for calculating the actual torque and thrust commands applied to the drone. During this process, the ST-VTOL UAV model continuously updates the system states. These system states are fed back to each sub-controller to ensure closed-loop stability and robustness.

The proposed control framework satisfies the following properties: the high-bandwidth roll–yaw PID inner loops maintain lateral-directional stability and rapidly suppress small-angle deviations caused by crosswinds, while the low-bandwidth longitudinal SSMC governs pitch and altitude dynamics under dominant aerodynamic and thrust disturbances. Within the specified operating envelope—small attitude angles, unsaturated actuators, and weak cross-axis coupling—the outputs of both controllers can be linearly superposed through the control allocation module. This linear superposition ensures consistent torque and thrust distribution among actuators and allows the overall closed-loop system to maintain stability and robustness.

The following subsections provide more detailed calculations and derivations of each controller component.

3.1. Roll and Yaw Attitude Controller

The lateral control objective is to regulate the ST-VTOL UAV’s roll and yaw angles to their desired reference values, i.e.,

and

.

is derived from attitude control requirements.

because the ST-VTOL UAV achieves its maximum wind resistance when its heading angle and wind speed are aligned, as described in

Section 2. In this case, the dynamic model can also be simplified to 3 degrees of freedom. Furthermore, in

Section 4.3, the direction of the maximum wind speed generated by the experimental equipment is parallel to the ST-VTOL UAV’s heading, which also ensures the rationality of the

control target setting.

To this end, conventional PID controllers are implemented independently for the roll and yaw channels. The control laws are defined as follows.

For the roll channel:

where

denotes the roll control input,

is the roll tracking error,

is its time derivative, and

represents the time variable of integration. The parameters

,

, and

are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively, tuned to ensure fast transient response and elimination of steady-state error.

For the yaw channel:

where

is the yaw control input,

denotes the yaw tracking error, and

is its time derivative. Similarly,

,

, and

are the PID gains governing the yaw loop.

By independently regulating roll and yaw angles, these PID controllers ensure that the ST-VTOL UAV maintains lateral stability and effectively suppresses deviations from the commanded attitude.

3.2. Horizontal Position Controller

The horizontal position controller generates

, the input to the subsequent longitudinal control loop. This controller is designed to combine position and velocity feedback in a nested structure. The position error is defined as

, and the velocity error is expressed as

. The control law is given by:

where

and

are the proportional gains for position and velocity feedback, respectively. This formulation ensures that both the horizontal displacement and velocity are simultaneously regulated.

3.3. Attitude and Pitch Altitude Controller

The altitude and pitch attitude controller is implemented using an SSMC.

3.3.1. Control Model

The total disturbance term accounts for model errors resulting from uncertain wind direction and time-varying aerodynamic disturbances encountered during flight. This modeling approach simplifies subsequent controller design because any deviation from the nominal aerodynamic force calculation can be equivalently treated as an additional disturbance in the system dynamics. This paper reconstructs the dynamic model (

9) and expresses it in state space form.

Since the primary control objective is to regulate pitch motion and altitude, the choice of system states is limited to the longitudinal channel. The state vector is defined as . This reduced-order representation captures the main dynamics relevant to the hovering task while neglecting the lateral states, which are independently stabilized by the roll-yaw control loop described earlier.

The state-space model is represented as follows:

where

and

are the system and input matrices obtained by linearizing the nonlinear ST-VTOL UAV dynamics near the hovering equilibrium point. The control input vector

.

The disturbance term is defined as

, where

represents the concentrated disturbance acting on the pitch acceleration

, and

represents the concentrated disturbance acting on the vertical acceleration

, as shown in Equation (

9). In practice,

and

are time-varying and difficult to model explicitly. Therefore, an observer-based approach is necessary to estimate these disturbances in real-time and provide the necessary compensation in the control loop.

Based on this reconstructed model, the altitude and pitch controllers can be reformulated using a unified state-space representation, which facilitates the design of the robust disturbance rejection control law presented in the following sections.

3.3.2. State Observation and Disturbance Estimation

To enhance the disturbance rejection capability of the controller, the total disturbance is modeled as an extended state

. The complete observer state is thus defined as

, where

,

, and

. The corresponding extended system derived from (

16) is given by:

where

represents the unknown but bounded disturbance vector, which is continuously differentiable in this context. The derivative matrix

,

,

from

and

are as follows:

Based on Equation (

17), this paper designs an SCFO. Unlike traditional ESOs, which directly enhance disturbances by adding states, SCFO adds

to

, and introduces a first-order integral in

to follow the slowly varying/curvature of the unknown perturbation. The SCFO dynamic process is represented as follows:

where

is the estimated value of

. The error vector is defined as

, in which

.

are the coefficients of the compensation function. Also, the observer gains

.

Stability Analysis of the SCFO. The stability analysis proceeds by first establishing the uniform exponential stability of the nominal error dynamics, and then analysing the effect of perturbations.

The complete error vector is defined as:

The estimation error of the disturbance output is:

Subtracting the SCFO equations from the extended system yields:

which can be written in a compact LTV form as:

where

, and:

The closed-loop matrix is:

which gives:

Next, we need to make several key assumptions:

Assumption 1. (Bounded matrices) and are uniformly bounded: for all , ,.

Assumption 2. (Uniform complete observability) The pair is uniformly completely observable.

For the ST-VTOL UAV model under consideration, the state matrices vary primarily with the flight speed and the angle of attack, both of which are physical quantities with bounded rates of change. Under these conditions, and given that the system is physically observable throughout all expected flight regimes, Assumption 2 is considered to hold. The gain matrices and are chosen to be sufficiently large so as to satisfy the observability Gramian condition over a finite interval.

Lemma 1. If is uniformly completely observable, its dual is uniformly completely controllable. Hence, there exists a constant gain such that is uniformly exponentially stable [42]. Therefore, according to Lemma 1, we can choose constant gain matrices , , , and (which define the block structure of ) such that is uniformly exponentially stable.

Assumption 3. (Bounded disturbance derivative) For all , the disturbance rate satisfies .

Under Assumptions 1–3, with the gains chosen as above, system (

23) is input-to-state stable (ISS) and

is uniformly ultimately bounded.

Consider the nominal case

:

From Assumption 2 and Lemma 1, the matrix

is uniformly exponentially stable.

Lemma 2. A time-varying system is uniformly exponentially stable if and only if there exists a continuously differentiable symmetric matrix and constants such that and [43]. Although an explicit form of

may not be readily available, Lemma 2 guarantees the existence of such a function, which is sufficient for the analysis. Accordingly, there exists a time-varying Lyapunov function:

satisfying:

Now consider the perturbed system with

. Differentiating

along trajectories of (

23) yields:

By inequality (

29) and applying the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, we obtain:

Since

and

, defining

gives:

Lemma 3. If there exists a Lyapunov function such thatthen the system is uniformly ultimately bounded [43]. The inequality (

32) satisfies the conditions for ISS. According to Lemma 3, system (

23) is ISS, which implies uniform ultimate boundedness (UUB). Therefore, there exist constants

and a class-

function

such that:

Since

,

, and

are contained in

and

are constant,

in (

21) is also uniformly ultimately bounded. Therefore, under the given assumptions, the SCFO guarantees exponential convergence of

in the nominal case (

) and uniform ultimate boundedness of both

and the disturbance estimation error under bounded disturbance derivatives.

3.3.3. Equivalent Sliding Mode Controller Design

During the controller design, the improved SCFO is assumed to provide accurate estimates of the system states and disturbances, i.e., . Under this assumption, the ESMC law can be constructed by combining three mechanisms: equivalent dynamics cancellation, nonlinear switching, and disturbance compensation.

The sliding surface is designed as:

where

is a user-defined weighting matrix and

denotes the state tracking error. The matrix

determines how each component of the error contributes to the sliding surface, and must satisfy that

is nonsingular. This full-rank condition guarantees the existence of an equivalent control input. For the hovering control objective, the reference trajectory is constant, i.e.,

.

The time derivative of the sliding surface can be derived from the state-space dynamics as:

where

. Once the sliding condition is satisfied, the system motion is constrained to the sliding manifold

. On this manifold, the equivalent control is obtained by enforcing

, leading to:

The equivalent control thus cancels the nominal system dynamics along the sliding surface, ensuring that the closed-loop trajectories remain confined to the manifold under ideal conditions.

To guarantee convergence toward the sliding manifold in the presence of uncertainties, a nonlinear switching term is introduced:

where

is the switching gain matrix and

is a small smoothing factor used to mitigate chattering. The function

serves as a continuous approximation of the discontinuous

function, ensuring smooth control behavior near the sliding surface. A sufficiently large

is required to compensate for model uncertainties and external disturbances.

To further reduce the dependence on large switching gains, disturbance compensation is introduced based on the SCFO estimation:

where

is the disturbance estimate provided by the observer.

Incorporating this compensation term effectively suppresses residual oscillations and improves steady-state accuracy. Consequently, the final control law of the ESMC is expressed as:

Stability Analysis of the ESMC. The stability of the composite system SSMC is analyzed. The analysis builds upon the established performance of the SCFO, which is formalized in the following assumption:

Assumption 4. (Observer Performance) The SCFO guarantees that the state and disturbance estimation errors are uniformly ultimately bounded. Specifically, from the ISS result of the SCFO in (33), there exists a constant and a finite time such that the residual disturbance estimation error satisfies: Consider the Lyapunov function candidate:

Differentiating

along the trajectories of the system and substituting the control law (

39) yields the sliding dynamics:

The derivative of the Lyapunov function is:

Applying the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality and the bound from Assumption 4:

Lemma 4. The system is ISS if there exists a class function and a class function γ such that: From inequality (

44), we observe that

satisfies the conditions for ISS. Therefore, the sliding mode dynamics are ISS with respect to the disturbance estimation error

.

The composite observer–controller system can be viewed as a feedback interconnection:

Let be the ISS gain of the SCFO from to , and let be the ISS gain of the ESMC from to , which in turn affects the SCFO through the system dynamics. Furthermore, with the SCFO gains chosen sufficiently large to ensure a small disturbance estimation error bound , the overall system is uniformly ultimately bounded.

Under Assumptions 1–4, the ESMC ensures that the sliding variable

converges to a residual set around the origin. Specifically, there exists a finite time

and a constant

such that:

where the ultimate bound

is given by:

Proof. From (

44), we have

whenever

Solving the above inequality for

yields that

for all

, where

is defined in (

47). □

Corollary 1. In the ideal situation where the disturbance estimation is perfect () and the smoothing factor is removed (), the sliding variable converges asymptotically to the origin. Specifically, the closed-loop system satisfiesand the control law in (39) guarantees perfect tracking performance. Design Guidelines. The stability analysis provides explicit criteria for selecting the ESMC parameters:

Switching Gain Condition:

To ensure robustness, the switching gain must dominate the worst-case disturbance estimation error, i.e.,

Smoothing Factor: The parameter should be selected as a compromise between chattering suppression (larger ) and steady-state accuracy (smaller ).

Observer–Controller Co-design: The ultimate accuracy is proportional to both and . Therefore, improving the observer’s estimation quality (reducing ) allows the designer to choose a larger to suppress chattering without degrading the tracking performance.

The complete execution process of the proposed disturbance rejection controller, including lateral stabilization, horizontal position regulation, state observation, and sliding mode compensation, is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Disturbance Rejection Control Process |

- 1:

Initialize reference commands - 2:

Initialize SCFO states - 3:

while Safety fly action is active do - 4:

Lateral attitude control: - 5:

Compute roll control using Equation ( 13) - 6:

Compute yaw control using Equation ( 14) - 7:

Horizontal position control: - 8:

Generate using Equation ( 15) - 9:

Longitudinal channel with SCFO: - 10:

Update system states - 11:

Estimate using Equation ( 19) - 12:

Compute disturbance estimate using Equation ( 19) - 13:

ESMC law: - 14:

Calculate using Equation ( 36) - 15:

Calculate using Equation ( 37) - 16:

Compute final longitudinal control using Equation ( 39) - 17:

Control allocation: - 18:

Combine and send to allocation module - 19:

Apply allocated torque and thrust commands to ST-VTOL UAV - 20:

end while

|

The control methodology and its implementation framework have now been fully established. Based on this, the following section evaluates the proposed design through simulation and flight experiments.

5. Conclusions

This paper is the first to apply the SSMC method to an ST-VTOL UAV. The goal is to investigate the practicality of this approach for maintaining stability during take-off and landing under wind disturbances. The state observer employed, the SCFO, differs from the traditional LESO in that it explicitly incorporates system derivatives in its formulation. This improvement enhances the accuracy of the state observation, thereby making disturbance estimation more reliable.

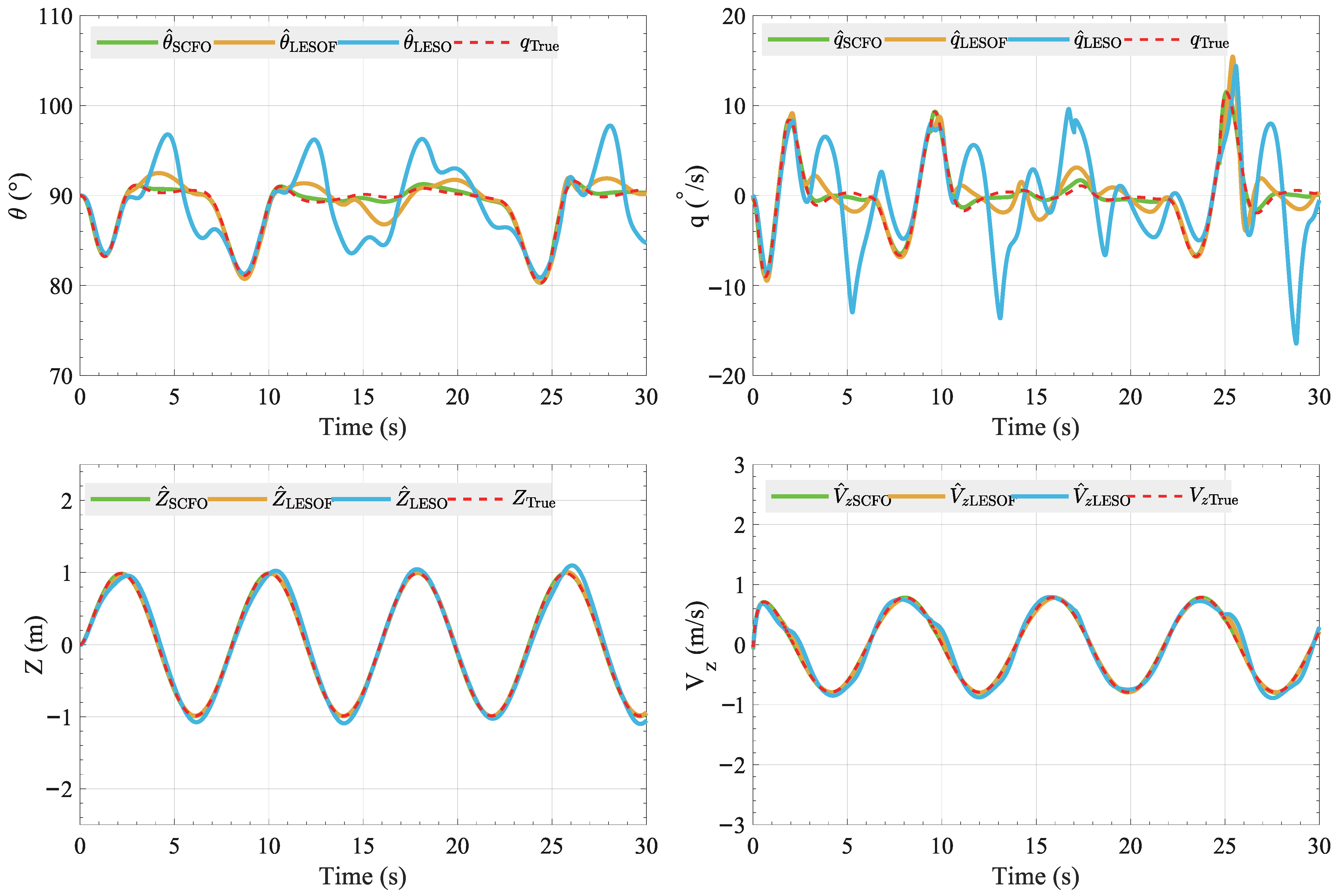

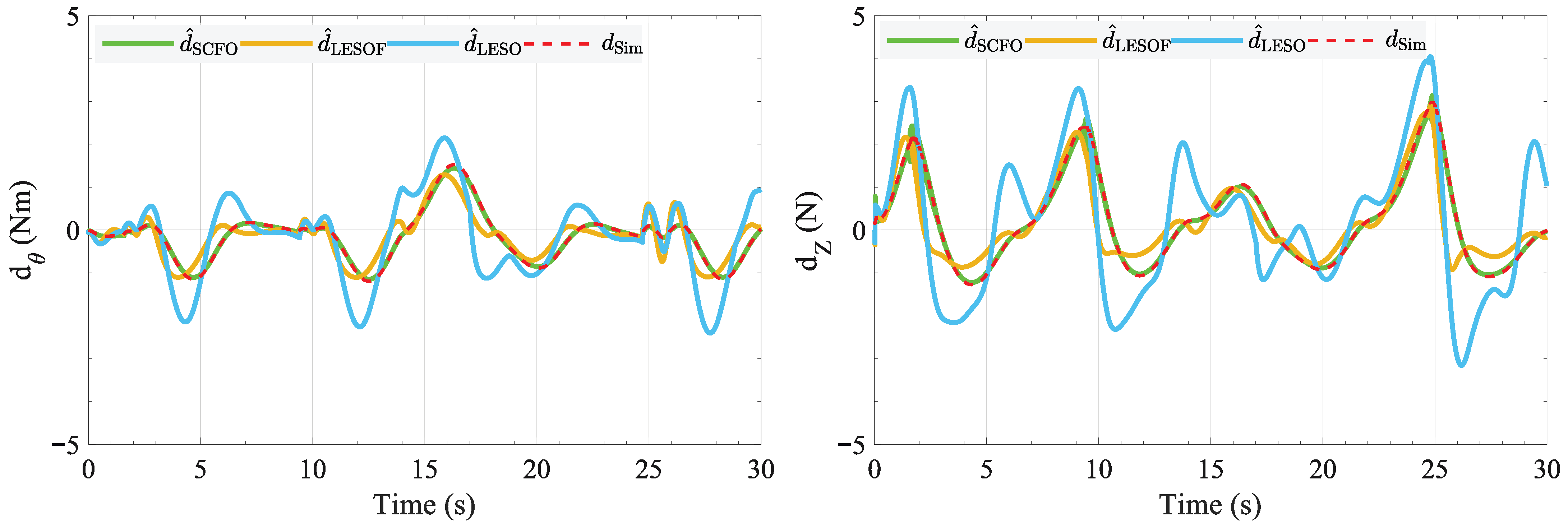

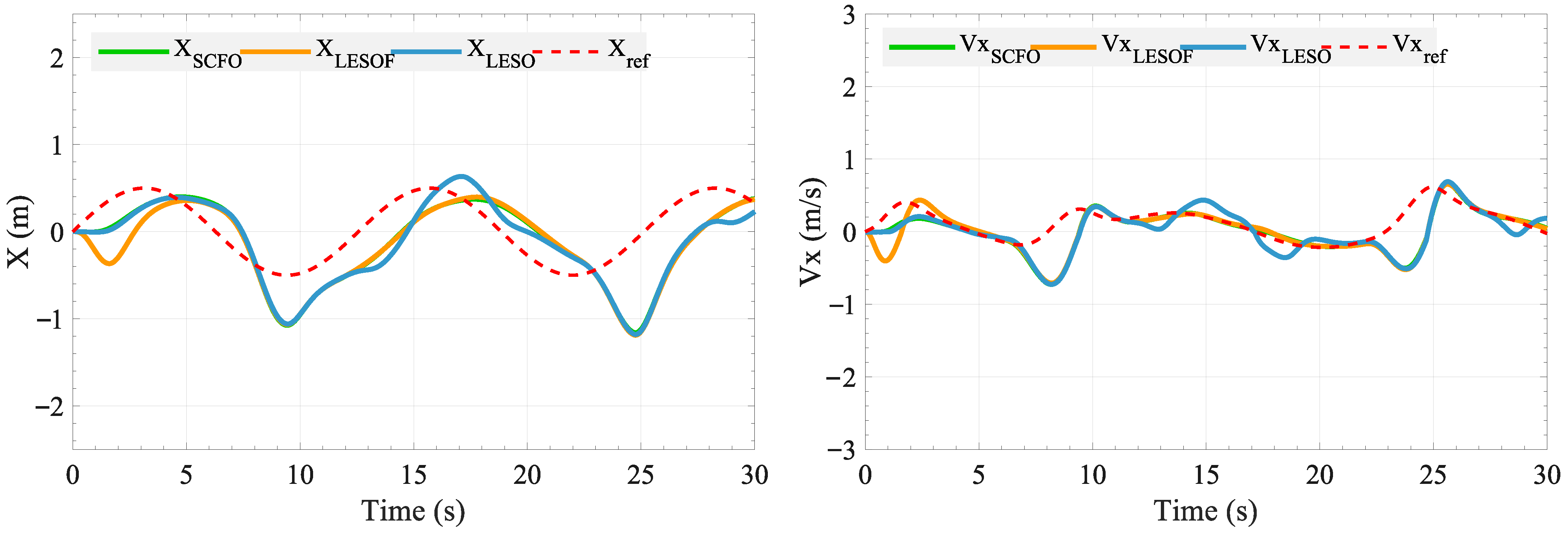

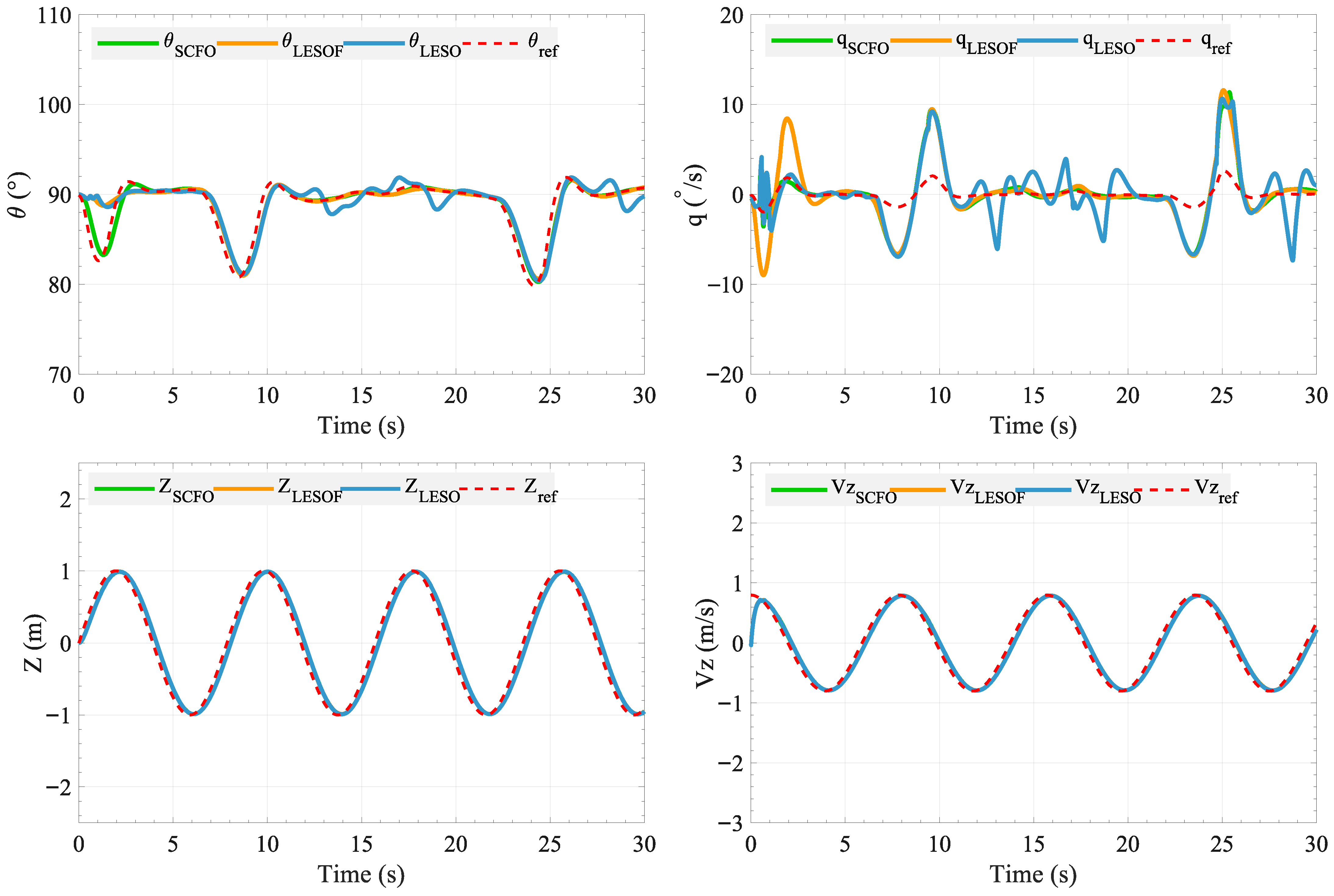

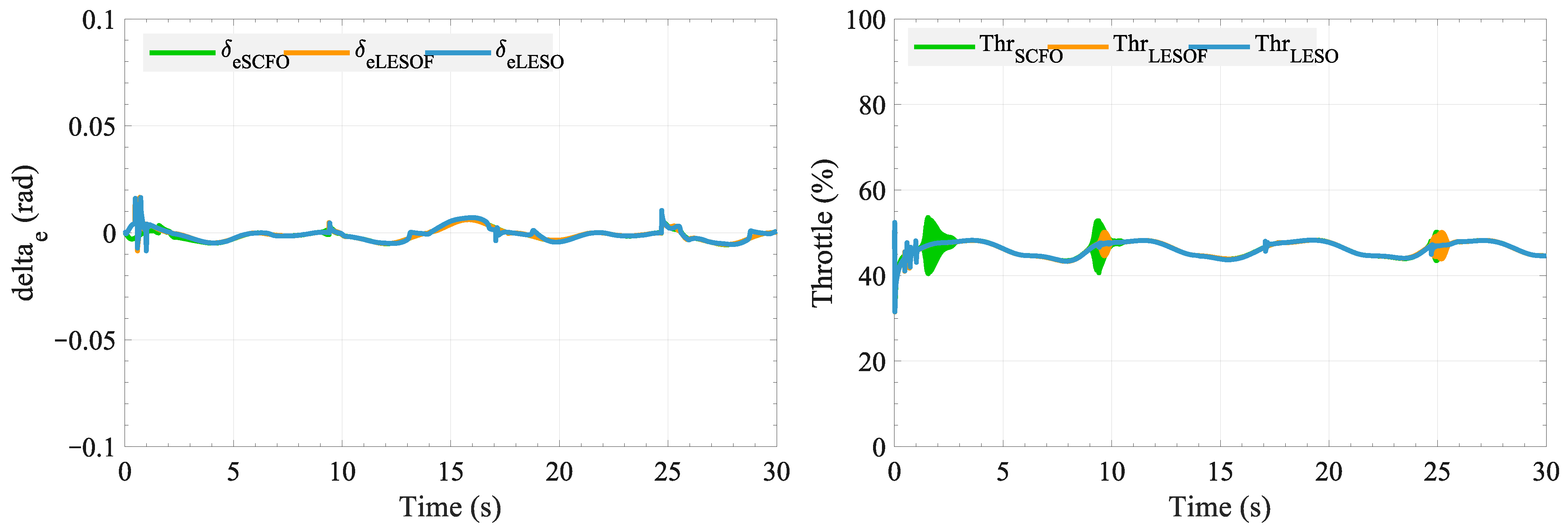

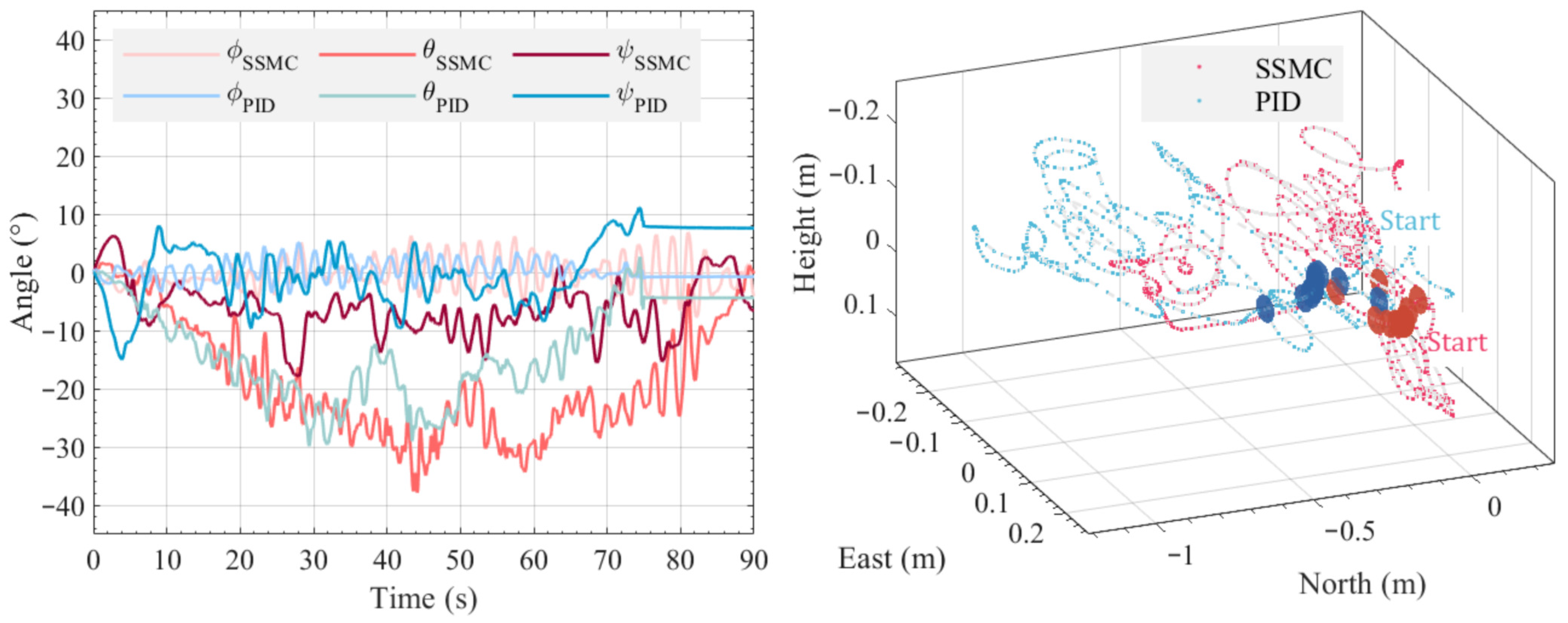

Firstly, a complete 6-DOF dynamic model was established, along with a simplified 3-DOF longitudinal model that incorporates disturbance representation. Subsequently, the SCFO was combined with the ESMC to design the SSMC controller. The control variables input to the ST-VTOL UAV include an equivalent control term, a nonlinear switching term, and a disturbance compensation term. A theoretical Lyapunov-based stability analysis shows that the closed-loop error dynamics exhibit asymptotic convergence in the nominal case and remain uniformly ultimately bounded in the presence of bounded disturbance derivatives and estimation residuals. Finally, the proposed SSMC method was validated through both simulations and flight experiments under external disturbances, utilizing an experimental platform comprising a FAWG, an indoor motion-capture testbed, and a lightweight ST-VTOL prototype. Simulation results demonstrated that the SCFO-based control achieved the smallest tracking errors among all observers, with RMSE reductions of up to 65% in pitch angle and 88% in altitude compared to the LESO-based scheme, confirming its superior disturbance estimation and compensation capabilities. Experimental evaluations further revealed that the SSMC reduced the total tracking error by approximately 33%, decreased the RMSE from 0.65 to 0.42, and limited the maximum deviation by 27% compared to the PID controller. These results collectively verify that SSMC ensures faster convergence, smaller steady-state errors, and more stable flight performance under disturbance conditions. This demonstrates the technical advantages of combining a derivative-based observer structure with an SMC law and the practicality of this approach for ST-VTOL UAVs.

Future research will explore integrating of this control approach with an MPC framework, extending the flight mission from fixed-point hovering to trajectory tracking, thereby further improving the engineering applicability of this approach and the ST-VTOL UAV.