Abstract

Burgeoning air pollution is a pressing public health concern. However, due to the scarcity and sparsity of ground-based monitoring, its impact remains uncertain. This work demonstrates how satellite-derived NO2 observations can identify persistent pollution hotspots and seasonal patterns in a data-scarce urban region. This work leveraged TROPOMI satellite data and Google Earth Engine to evaluate tropospheric NO2 hotspot patterns in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana from 2019 to 2023. TROPOMI data revealed persistent NO2 hotspots in urban and industrial areas, with overall peak concentrations reaching up to 3.3 × 1015 mol cm−2. Seasonal analysis showed elevated NO2 levels during the dry season, with a mean concentration of 2.3 × 1015 mol cm−2, while lower levels were observed during the rainy season. Increased emissions and reduced dispersion influence this pattern due to stable atmospheric conditions. Google Earth imagery confirmed that the highest NO2 concentrations were associated with the Heavy Industrial Area, highlighting the presence of extensive industrial facilities such as refineries, factories, and quarries. This integration of satellite observations with high-resolution geospatial tools provides a robust methodology for NO2 source attribution, emphasizing the need for targeted emission control measures in industrial zones to mitigate air pollution and associated health risks.

1. Introduction

Air pollution has emerged as a significant environmental and public health challenge, especially in rapidly urbanizing regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Among the various pollutants, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) plays a crucial role due to its adverse effects on respiratory health and its contribution to the formation of ground-level ozone and secondary particulate matter. NO2 is primarily emitted from anthropogenic sources such as vehicular traffic, industrial activities, and residential [1,2,3]. Recent advancements in satellite-based remote sensing have enabled high-resolution monitoring of atmospheric NO2 on a global scale. However, while satellite data provide valuable information on the spatial and temporal variability of NO2, they do not inherently attribute the observed concentrations to specific emission sources [2].

Traditional source attribution relies on ground-based measurements and sophisticated chemical transport models, which are often resource-intensive and limited by spatial coverage, especially in regions where monitoring infrastructure is sparse [4,5]. In some cases, samples needed to be cold-couriered to laboratories in another country for chemical analytical evaluation [3]. This gap hinders the effective implementation of targeted air quality management and pollution control. A promising alternative to achieve this daunting task, though very little explored, is the integration of high-resolution satellite observations with on-the-ground information to accurately pinpoint pollutant sources at a localized level. A close effort is the report by Shehzad et al. [6] and similar works which identified major pollution sources scattered across north-east India and their post-COVID-19 abated emissions using Sentinel-5P satellite [7,8,9]. However, as mentioned, precise attribution is left to guesswork.

Beyond satellite-based monitoring, several technologies are widely used for air quality assessment. Regulatory-grade NO2 measurements rely primarily on chemiluminescence analyzers and optical absorption systems such as UV–Vis and cavity ring-down spectroscopy. In recent years, dense low-cost sensor networks based on electrochemical sensing have gained attention for enhancing spatial coverage in lower-income regions [10,11,12]. These complementary systems help quantify near-surface pollutant concentrations and provide valuable ground-truthing opportunities for satellite observations, although their availability remains limited in many regions. Including satellite NO2 therefore fills an important observational gap in regions where routine ground-based monitoring remains sparse or absent.

This work proposes an approach to bridge this gap by leveraging the capabilities of the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite combined with earth surface imagery from Google Earth to perform a source attribution of tropospheric NO2 over the Greater Accra region. This integrated approach offers a low-cost, scalable solution to identify and quantify major NO2 sources without the need for extensive ground-based monitoring networks. The technical innovation of this approach lies in the utilization of Google Earth’s detailed spatial imagery to visually identify and categorize potential NO2 sources, such as traffic congestion points, industrial zones, and residential areas. By overlaying the Earth maps with high-resolution NO2 concentration maps derived from TROPOMI data, an innovative method for spatially attributing air pollution sources is introduced. By identifying the hotspots of NO2 pollution and their associated sources, targeted mitigation strategies can be developed to improve air quality and protect public health. Moreover, the methodological framework established in this study can be applied to other rapidly urbanizing cities in Africa and beyond.

2. Methodology

2.1. Geography and Climatology of Study Area

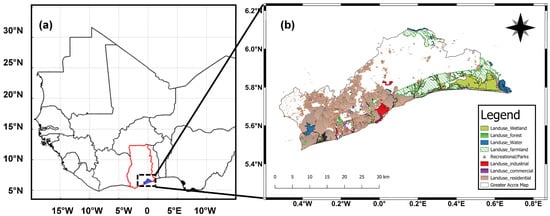

The Greater Accra Region, located in the southern part of Ghana, is among the most rapidly urbanizing regions in the country. It serves as the political and administrative capital, hosting the city of Accra, and is characterized by significant industrial activities, vehicular emissions, and biomass burning, all contributing to elevated levels of atmospheric pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide (NO2). The geographical extent of the Greater Accra Region spans from approximately 5.3° N to 6.2° N latitude and −0.6° W to 0.8° E longitude (Figure 1). The region’s dense population and economic activities make it a key area for air quality assessment and pollution source attribution [3].

Figure 1.

Study area map showing (a) the geographical location of the Greater Accra Region of Ghana (in red border), and (b) land-use and industrial classification.

To provide spatial orientation and to support hotspot interpretation, a land-use and industrial-source map of the Greater Accra Region was developed using QGIS 3.40.13. The administrative boundary was obtained from the GADM (Global Administrative Areas) database at https://gadm.org/download_country.html (accessed on 6 December 2025), while land-use layers were extracted from OpenStreetMap (OSM) using the QuickOSM plugin. Relevant classes included residential, commercial, industrial, farmland, forest, recreational/park areas, wetlands, and water bodies. The resulting map in Figure 1b highlights the major industrial and commercial corridors. This map enables a clearer interpretation of TROPOMI-derived NO2 concentrations, especially given the 0.1° (~10 km) resolution of Level-3 data, which constrains source attribution to the zone scale rather than individual facilities.

The climatology of the Greater Accra Region is coastal savannah, influenced by the West African monsoon system, which governs seasonal variability in temperature, wind flow, and boundary-layer dynamics. The year comprises a dry Harmattan season (December–February) dominated by northeasterly continental winds, a pre-monsoon warming period (March–April), the onset of the southwesterly monsoon (May–June), and the peak monsoon period (July–September). Temperature typically peaks between February and April (~30–33 °C) and decreases slightly during the monsoon due to increased cloudiness and moisture [3].

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. TROPOMI NO2 Data

The primary dataset for this study is the TROPOMI Level 3 GLOBAL NO2 dataset provided by the NASA Health And Air Quality Applied Science Team (HAQAST). This dataset, available at a 0.1° × 0.1° resolution, provides monthly averaged tropospheric NO2 column densities from 2019 to 2023. The TROPOMI instrument, on board the Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite, offers high spatial resolution and global coverage, making it suitable for capturing the spatial distribution and temporal evolution of NO2 [13,14]. This passive optical sensor relies on solar UV-visible radiation, capturing radiance in the 405–465 nm spectral window to derive NO2 column amounts through differential optical absorption spectroscopy [15]. The data was accessed from the NASA Earthdata portal at https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search?q=HAQ_TROPOMI_NO2_GLOBAL_M_L3 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

To identify areas with high NO2 concentrations, a threshold value was determined using the mean and standard deviation of the NO2 data:

where μ is the mean NO2 concentration and σ is the standard deviation. Data points exceeding this threshold were marked as high NO2 areas. This follows standard anomaly detection practice, in which multi-sigma exceedance limits (typically 2–3σ) are used to isolate strong enhancements above background noise in satellite trace-gas products [16]. At the 0.1° resolution of the TROPOMI Level-3 data, a 2.5σ threshold provides a conservative balance between detecting localized enhancements and avoiding spurious hotspots, effectively focusing on the upper tail of the NO2 distribution (approximately the 97–98th percentile).

Additionally, to strengthen the temporal interpretation of the satellite observations, statistical tests were applied to the monthly mean NO2 time series over the study period of 2019–2023. Long-term trends were evaluated using the non-parametric Mann–Kendall test, which is robust for non-normally distributed atmospheric datasets. Seasonal differences were tested using one-way ANOVA applied to the monthly averages assigned to the four climatological seasons (DJF, MAM, JJA, SON). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

2.2.2. Google Earth Imagery

Satellite imagery from Sentinel-2, processed via Google Earth Engine (GEE), was combined with TROPOMI NO2 data to visually inspect NO2 hotspots. Cloud-free imagery was produced using a cloud masking algorithm, which removed cloud and cirrus pixels based on the QA60 band from Sentinel-2 data [17]. A median composite of cloud-free Sentinel-2 imagery was generated to provide a stable background. A transparent version of the TROPOMI NO2 data, was overlaid on the Sentinel-2 composite to show NO2 concentrations over the study area. This allowed for the identification of pollution hotspots. The NO2 column densities were analyzed directly, linking higher concentrations to known industrial zones, and densely populated urban regions. This combined approach of satellite imagery and NO2 measurements enhanced the identification of emission sources. It is important to note that the Google Earth overlays are used solely for spatial context and not for quantitative source attribution. The purpose of this step is to identify land-use characteristics within hotspot zones rather than to determine emission strengths.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. NO2 Distribution Pattern

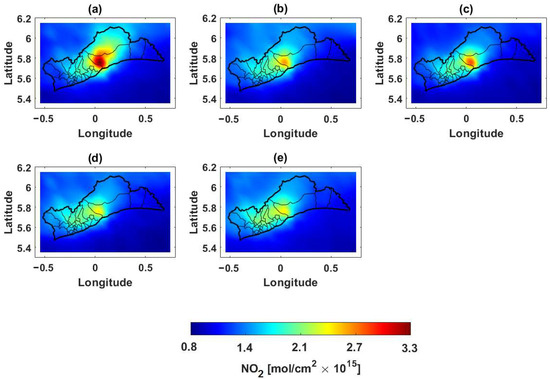

The spatial distribution of annual mean tropospheric NO2 over the Greater Accra Region from 2019 to 2023 is presented in Figure 2. Generally, a distinct hotspot residing in the central part of the region is identified as shown in Figure 2a–e. This area, which includes the urban centers of Accra and Tema, is characterized by heavy traffic, industrial activities, and residential emissions, contributing to elevated NO2 levels. The hotspot area aligns spatially with major industrial and high-traffic land-use zones identified in the reference land-use map in Figure 1, providing independent contextual support beyond visual inspection alone. In 2019 (Figure 2a) the concentration of NO2 in this region ranges between 2.5 and 3.3 × 1015 mol cm−2. In 2020 (Figure 2b) the distribution shows a noticeable reduction, with the hotspot becoming less intense compared to 2019. This reduction may be attributed to the implementation of COVID-19 lockdown measures, which led to reduced vehicular traffic and industrial activities. In 2021 (Figure 2c), a slight increase in NO2 levels is observed compared to 2020. The relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions and the subsequent resumption of economic activities likely contributed to this increase. The spatial pattern shows a re-emergence of the NO2 hotspot in the central region, with concentrations again reaching up to 3.0 × 1015 mol cm−2. The 2022 NO2 distribution, depicted in Figure 2d, indicates a more dispersed pattern of NO2, with lower concentrations over the previously identified hotspot areas. This dispersion could be attributed to changes in meteorological conditions and land-ocean-atmosphere dynamics. Despite this, certain areas still exhibit elevated NO2 levels, indicative of persistent local sources. Finally, Figure 2e exhibits a pattern similar to 2022, but with a slight increase in concentration across the region. The mean concentration over Greater Accra remains elevated, indicating ongoing air quality challenges. Similar attributive post-COVID-19 emission patterns have been reported for India [6], China [18], and Europe [19].

Figure 2.

Annual mean NO2 distribution over Greater Accra during 2019–2023 (a–e).

Overall, the spatiotemporal pattern of NO2 over Greater Accra from 2019 to 2023 highlights the characteristic nature of pollutant distribution. The persistent hotspot in central Greater Accra suggests that targeted air quality management strategies are required to mitigate emissions from key sources. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures provides a natural experiment demonstrating the potential benefits of reduced emissions on air quality. The elevated NO2 levels in central enclave are mainly due to a conglomerate of heavy vehicular emissions and industrial activities, where manufacturing and energy production are concentrated [3]. attributed the highest NO2 contributions to commercial, industrial, and high-density residential areas. Meteorological factors, like wind patterns and temperature inversions during the harmattan season, also play a role in the distribution and accumulation of pollutants.

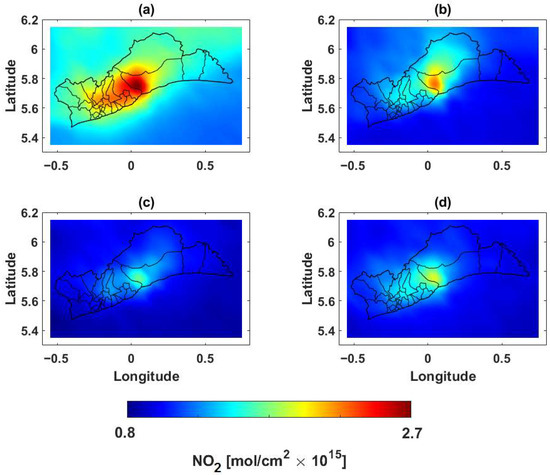

Figure 3 illustrates the seasonal variability of NO2 concentrations over Greater Accra from 2019 to 2023. Elevated NO2 levels are observed during the December-February (DJF) dry season (Figure 3a), likely due to lower wind speeds and stable atmospheric conditions that limit dispersion [3,20]. This period also coincides with increased open biomass burning and fuel combustion activities during the harmattan season, which enhances pollutant accumulation. In contrast, the March-May (MAM, Figure 3b) and June-August (JJA, Figure 3c) seasons exhibit relatively lower NO2 concentrations, attributed to improved atmospheric mixing and pollutant dispersion, as well as rain washout. The September-November (SON, Figure 3d) season shows a slight increase in NO2 levels, attributive to the short non-rainy period commencing the minor wet season [21].

Figure 3.

Seasonal mean NO2 distribution over Greater Accra during (a) December–February (DJF), (b) March–May (MAM), (c) June–August (JJA), and (d) September–November (SON) spanning 2019–2023.

The Mann–Kendall test revealed no statistically significant regional trend in NO2 over the 2019–2023 period (τ = –0.066, p = 0.481), indicating the absence of a monotonic increase or decrease in monthly concentrations. In contrast, seasonal differences were highly significant, with a one-way ANOVA yielding F = 72.13 and p = 3.14 × 10−19 (see Table 1). These results confirm that meteorological seasonality exerts a dominant influence on NO2 levels in the region, consistent with the higher concentrations observed during the Harmattan and pre-monsoon periods.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of NO2 temporal variability for the Greater Accra Region (2019–2023).

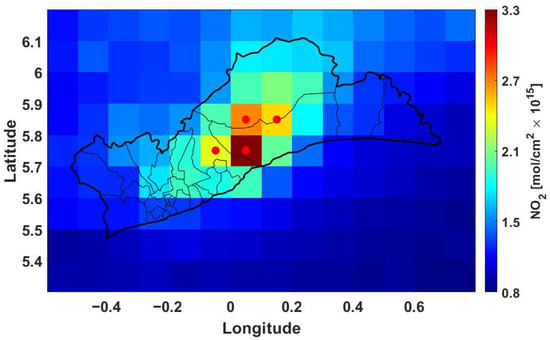

3.2. NO2 Hotspot Regions

The identification of NO2 hotspots within the Greater Accra region, as shown in Figure 4, highlights areas where NO2 concentrations exceed the mean by 2.5 standard deviations. The geographical coordinates of these hotspots, presented in Table 2, correspond to locations with significant emission sources [3]. These hotspots are the urbanized zones, and the proximity to major roads and industrial districts, as pointed out by Wang et al. [3], further supports the attribution of these NO2 peaks to vehicular emissions and industrial discharges. Additionally, the seasonal variation observed in these hotspots, with elevated levels during the dry season (DJF), suggests the potential influence of reduced dispersion and accumulation of pollutants due to lower atmospheric mixing.

Figure 4.

NO2 hotspot (indicated by red dots) for mean concentration + 2.5 standard deviations.

Table 2.

NO2 hotspot geographical enclave locations in Accra, Ghana.

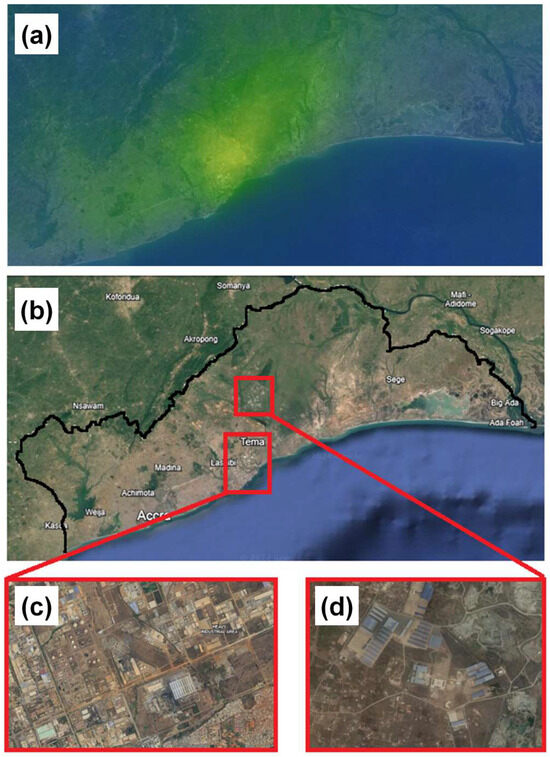

3.3. Google Earth Assisted NO2 Source Identification

Figure 5a shows the superimposed TROPOMI NO2 on cloud masked Sentinel-2 imagery, allowing for visual inspection and attribution of emision sources. Figure 5b isolates the cloud masked Sentinel-2 imagery, illustrating the geographical positioning of the hotspots, predominantly clustered around the Tema Heavy Industrial Area enclave. It is worth mentioning that the NO/ NO2 measurement network designed by Wang et al. [3] corroborates the high emission profile observed here. By zooming into the satellite imagery (Figure 5c,d), specific industrial infrastructures that serve as major NO2 emission sources are identified. The detailed examination of these areas reveals a dense network of industrial facilities, including factories, refineries, power plants, and manufacturing units [22]. The proximity of these facilities to residential areas exacerbates the potential health impacts of NO2 emissions. For instance, the Tema Industrial Area, highlighted in Figure 5b, houses numerous large-scale industries, such as cement factories, steel plants, and chemical processing units. Similarly, the imagery in Figure 5d, focusing on areas adjacent to the industrial zones, indicates the presence of additional facilities such as logistics warehouses and smaller manufacturing units. These sites contribute cumulatively to the high NO2 levels observed in the region [23]. The spatial correlation between these industrial activities and elevated NO2 concentrations strongly suggests that emissions from these sources are a major factor in the pollution profile of Greater Accra [3]. Furthermore, the use of Google Earth allowed for the identification of specific emission sources, such as smokestacks, storage tanks, and large vehicular fleets, which are difficult to capture through satellite data alone [24].

Figure 5.

High-resolution Google Earth Engine (GEE) maps showing (a) superimposed TROPOMI NO2 on cloud masked Sentinel-2 imagery, (b) isolated cloud masked Sentinel-2 imagery, and (c,d) expanded hotspot locations.

The integration of Google Earth imagery with TROPOMI data also highlights the limitations of using satellite observations alone for source attribution. While satellite data provides a comprehensive view of NO2 distribution over a broad area, it lacks the granularity required to pinpoint specific sources within densely populated urban environments. Google Earth imagery bridges this gap by providing visual evidence of potential sources, thus validating the hotspot analysis conducted through TROPOMI data.

Although hotspot regions overlap with industrial land-use zones, NO2 levels in Accra result from a combination of source types, including vehicular traffic, residential fuel combustion, small-scale manufacturing, and coastal shipping activities. The hotspot patterns presented in this study is thus an integrated enhancement reflecting combustion-related activities within each grid cell.

Admittedly, while Google Earth imagery provides high-resolution visual context for interpreting the spatial location of NO2 hotspot zones, it does not constitute quantitative source apportionment. The associations shown should therefore be interpreted as indicative patterns rather than confirmed emission contributions. Quantitative attribution would require ground-based measurements or high-resolution emission inventories, neither of which are currently available.

Furthermore, the absence of a city-scale NOₓ emission inventory and the lack of continuous NO2 ground monitoring stations in Accra limit the ability to independently verify satellite-derived hotspot patterns. Similarly, short-term measurement campaigns in Accra do not provide multi-year data suitable for validation. These data gaps highlight the need for integrated ground–satellite observation frameworks.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the spatiotemporal distribution of tropospheric NO2 over the Greater Accra Region from 2019 to 2023 using TROPOMI satellite observations. The analysis identified persistent NO2 hotspot zones, particularly within major urban and industrial corridors such as the Tema Industrial Area. Google Earth imagery provided spatial context for interpreting these enhancement zones, although it does not constitute quantitative source attribution. Seasonal patterns showed elevated NO2 during the dry season (December–February) and lower concentrations during the wet season (June–August), reflecting the combined effects of emission intensity and meteorological dispersion conditions. Beyond confirming expected seasonal and urban patterns, the main contribution of this work lies in demonstrating how satellite-derived NO2 products, together with geospatial mapping, can be used to systematically delineate hotspot regions in settings where ground-based monitoring and emission inventories are scarce. This integrated approach provides a practical framework for guiding air-quality management and prioritizing monitoring efforts in data-limited regions.

Author Contributions

P.J.A. and E.Q. conceptualized and wrote the main manuscript text. A.K.A. provided land-use and industrial classification map. P.B. and W.A. supervised and edited the text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The NASA Health And Air Quality Applied Science Team (HAQAST) Level 3 GLOBAL TROPOMI NO2 collections (Version 2.4) is available at: https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search?q=HAQ_TROPOMI_NO2_GLOBAL_M_L3. All resulting computational and statistical datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the NASA HAQAST Level 3 GLOBAL TROPOMI NO2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rus, A.A.; Pescariu, S.A.; Zus, A.S.; Gaiţă, D.; Mornoş, C. Impact of Short-Term Exposure to Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) and Ozone (O3) on Hospital Admissions for Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Toxics 2024, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, A.; Anenberg, S.; Goldberg, D.L.; Mohegh, A.; Brauer, M.; Hystad, P. A global spatial-temporal land use regression model for nitrogen dioxide air pollution. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1125979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Alli, A.S.; Clark, S.; Hughes, A.; Ezzati, M.; Beddows, A.; Vallarino, J.; Nimo, J.; Bedford-Moses, J.; Baah, S.; et al. Nitrogen oxides (NO and NO2) pollution in the Accra metropolis: Spatiotemporal patterns and the role of meteorology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Dai, Q.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Bi, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y. Spatial source apportionment of airborne coarse particulate matter using PMF-Bayesian receptor model. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, E.A.; Wang, Y.; Schulze, B.C.; Seltzer, K.M.; Yang, J.; Zhao, B.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, H.; Venecek, M.; Chau, D.; et al. An updated modeling framework to simulate Los Angeles air quality–Part 1: Model development, evaluation, and source apportionment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 2345–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, K.; Sarfraz, M.; Shah, S.G.M. The impact of COVID-19 as a necessary evil on air pollution in India during the lockdown. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, M.; Holloway, T.; Choi, S.; O’Neill, S.M.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Jin, X.; Fiore, A.M.; Henze, D.K.; et al. Methods, availability, and applications of PM2.5 exposure estimates derived from ground measurements, satellite, and atmospheric models. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1391–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaddick, G.; Thomas, M.L.; Green, A.; Brauer, M.; Donkelaar, A.; Burnett, R.; Chang, H.H.; Cohen, A.; Van Dingenen, R.; Dora, C.; et al. Data integration model for air quality: A hierarchical approach to the global estimation of exposures to ambient air pollution. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2018, 67, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.N.; Lamsal, L.N.; Thompson, A.M.; Yoshida, Y.; Lu, Z.; Streets, D.G.; Hurwitz, M.M.; Pickering, K.E. A space-based, high-resolution view of notable changes in urban NOx pollution around the world (2005–2014). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, N.; Dauge, F.R.; Schneider, P.; Vogt, M.; Lerner, U.; Fishbain, B.; Broday, D.; Bartonova, A. Can commercial low-cost sensor platforms contribute to air quality monitoring and exposure estimates? Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Morawska, L.; Martani, C.; Biskos, G.; Neophytou, M.; Di Sabatino, S.; Bell, M.; Norford, L.; Britter, R. The rise of low-cost sensing for managing air pollution in cities. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, F.D.; Gatari, M.; Ng’Ang’A, D.; Poynter, A.; Blake, R. Airborne particulate matter monitoring in Kenya using calibrated low-cost sensors. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 15403–15418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, J.P.; Aben, I.; McMullan, K.; Förster, H.; de Vries, J.; Otter, G.; Claas, J.; Eskes, H.J.; de Haan, J.F.; Kleipool, Q.; et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.L.; Anenberg, S.C.; Kerr, G.H.; Mohegh, A.; Lu, Z.; Streets, D.G. TROPOMI NO2 in the United States: A detailed look at the annual averages, weekly cycles, effects of temperature, and correlation with surface NO2 concentrations. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Geffen, J.; Boersma, K.F.; Eskes, H.; Sneep, M.; Ter Linden, M.; Zara, M.; Veefkind, J.P. S5P TROPOMI NO2 slant column retrieval: Method, stability, uncertainties and comparisons with OMI. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 1315–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirle, S.; Borger, C.; Dörner, S.; Li, A.; Hu, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wagner, T. Pinpointing nitrogen oxide emissions from space. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax9800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, F. Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 multi-temporal series to estimate topsoil properties on croplands. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; van der A, R.J.; Eskes, H.J.; Mijling, B.; Stavrakou, T.; Van Geffen, J.H.G.M.; Veefkind, J.P. NOx emissions reduction and rebound in China due to the COVID-19 crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL089912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakola, M.; Hernandez Carballo, I.; Jelastopulu, E.; Stuckler, D. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution in Europe and North America: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, J.; Monteiro, A.; Madureira, H. Temperature variability in coastal Ghana: A day-to-day variability framework. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 6351–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilevi, P.J.; Dogbey, F.; Boakye, P.; Aryee, J.N.A.; Yamba, E.I.; Owusu, S.Y.; Peprah, D.K.; Quansah, E.; Klutse, N.A.B.; Bentum, J.K.; et al. Bias-corrected NASA data for aridity index estimation over tropical climates in Ghana, West Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.; Yankson, P. Accra. Cities 2003, 20, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, O.C.; Njoku, C.; Akwuebu, A.N. Environmental impact of quarrying on air quality in Ebonyi state, Nigeria. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 33, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labzovskii, L.D.; Belikov, D.A.; Damiani, A. Spaceborne NO2 observations are sensitive to coal mining and processing in the largest coal basin of Russia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.