1. Introduction

Fractional-order derivatives have gained significant importance in real-world phenomenon due to their greater degree of flexibility in mathematical modeling as well as their ability to represent the inherited characteristics of several objects. Fractional-order operators are non-local in nature, whereas classical differential operators have local characteristics. A number of physical aspects can be effectively modeled through the use of fractional-order integrals and derivative theory. The importance of fractional calculus can be analyzed through the mathematical modeling of numerous rigorous phenomenon, e.g., rotational fluid flow [

1], seepage occurring in porous medium [

2], viscoelastic properties of polyethylene foams [

3], forecasting of national economic growth [

4], etc.

Classical PDEs are able to simulate various complex phenomena arising in the fields of fluid mechanics and biology and in many other areas of science and engineering. Non-linear convection–diffusion equations hold significant importance in the study of the propagation of nonlinear dispersive waves and traveling wave forms such as tidal oscillations, surface water waves in shallow rivers, and tsunami waves in a variety of disciplines including oceanography, hydrodynamics, acoustics, and marine engineering. Different researchers are working on developing efficient techniques to obtain analytical as well as numerical solutions for a variety of fractional-order models.

The generalized Burgers’-Huxley equation is one of the significant non-linear partial differential equations (PDEs) illustrating the relationships among reaction procedure, diffusion transports and convection outcomes [

5]. Furthermore, this equation also plays a crucial role in different domains such as biology, chemistry, engineering, mathematics, and so on. The model was originally brought into practice by Huxley [

6] and was later successfully developed by Burgers [

7] as a model to study the turbulent motion of fluids. Classical-order derivatives describe the behaviour of the dependent variable only at integer positions and do not provide any information regarding the behaviour between integer positions. Time fractional PDEs are derived from classical PDEs by substituting a fractional-order derivative in place of the temporal derivative. By including the fractional derivative term in classical PDEs, certain memory characteristics are incorporated into the system. The 1-D generalized non-linear fractional PDE is of the following form [

8]:

subject to following initial and boundary conditions:

By gathering source and convective terms into a general non-linear term, the above equation can be written as

where

denotes the order of fractional derivative,

is a real constant (coefficient of advection term),

(reaction coefficient),

is the coefficient of diffusivity, ∇ represents the gradient operator,

and

are real constants,

and

are known functions,

is the boundary operator,

is the source term, and

. By setting

,

,

, Equation (

1) reduces to the generalized Burgers’-Huxley equation illustrating relationships among reaction procedure, diffusion transports, and convection terms [

5]:

By choosing

, Equation (

1) is transformed into a generalized fractional Burgers’ Equation (

6) which describes many complex problems arising in the field of applied sciences, for instance, the propagation of waves in non-linear dissipative processes, ionic propagation in plasma, solid state physics, etc., [

9]:

For

= 0, Equation (

1) becomes a generalized fractional Huxley Equation (

7), which explains wall motion inside liquid crystals as well as the mechanism of nerve pulse propagation [

10]:

At

,

, Equation (

1) assumes the form of time fractional Burgers’-Huxley equation (TFBHE), which can be written as

Many definitions of fractional-order operators such as the Riemann–Liouville operator, Caputo’s definition, the Caputo–Fabrizio differential operator, the Atangana–Baleanu fractional operator, etc., have been proposed in the last few decades. Some preliminaries of fractional-order calculus are discussed here in order to understand the subsequent work.

(i) For

, the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order

defined on usual Lebesgue space

by [

11] is as follows:

For

f∈

,

,

and

, above operator has following properties:

(ii) The fractional-order derivative in terms of the Riemann–Liouville interpretation is [

12]

for

and

<

≤

p,

.

(iii) Caputo [

12,

13] proposed the definition of fractional operator as

where

and

p =

. Then,

(iv) For

p to be smallest integer that exceeds

, Caputo’s interpretation of the time-fractional derivative of the function

of order

is defined as follows [

12,

14]:

(v) For

be the function of space

(0,1), the Caputo–Fabrizio definition of fractional-order differentiation can be represented as [

15]

where

C(

) is a normalization function that satisfies a property as

C(0)=

C(1)=1.

(vi) Atangana and Baleanu [

16] introduced a novel definition based on the non-local and non-singular Mittag–Leffler kernel. For

∈

(0,1), the Atangana–Baleanu operator of order

∈

in the Riemann–Liouville sense can be expressed as follows:

In the case of Caputo, the above differential operator can be formulated as

where

C(

) denotes the normalization function and

(z)=

(z) represents the Mittag–Leffler function defined by [

12]:

where

denotes the Euler Gamma function,

and z∈

. Furthermore, the two-parameter Mittag–Leffler function is defined by [

12]

where

, z∈

and

.

In the literature, several models based on fractional PDEs have been solved by a variety of analytical and numerical methods. An implicit compact operator-based approximation is implemented in [

17] for numerical solution of time-dependent Burgers’-Huxley equation. Inc et al. [

18] studied a generalized Burgers’-Huxley model involving Riemann–Liouville formulation of the time-fractional derivative by utilizing lie symmetry analysis and a power series expansion approach. A residual power series approach is constructed in [

8] by combining Taylor’s series formula with residual error function for solving time-fractional Burgers’-Huxley model. Inc et al. [

19] investigated the solution of fractional Burgers’-Huxley equation using a combination method of line- and group-preserving schemes. In this study, the time-fractional derivative is defined by utilizing Caputo’s interpretation for derivatives.

Kumar and Pandey [

20] approximated the solution for spatial and temporal fractional-order Burgers’-Huxley models using the Atangana–Baleanu operator in the Caputo sense. The Legendre spectral method is applied for approximating space derivatives, while the temporal-order derivative is discretized via a finite difference scheme. In [

21], the existence of bifurcation of fractional Burgers’-Huxley models is examined for various situations of parameter

utilizing the residual powers series technique. Tripathi [

22] proposed an efficient fractional sub-equation approach in order to find three different types of analytical solutions for

nonlinear space–time fractional-order Burgers’-Huxley model. This study includes Jumarie’s modified Riemann–Liouville formulation for defining derivatives in spatial and temporal directions. Furthermore, a Fibonacci polynomials-based collocation approach is introduced in [

23] in order to solve variable order Burgers’-Huxley equations having fractional derivatives in spatial as well as temporal directions.

Mazeed et al. [

24] presented a collocation technique based on cubic polynomial splines for solving time fractional Burgers’-Huxley model. In this study, time derivatives are handled through a finite difference approach, while discretization of spatial derivatives is achieved using cubic B-splines as basis functions. For 1-D fractional Burgers’-Huxley models, Kanth et al. [

25] employed a natural transform decomposition procedure in which the fractional derivative was considered in terms of the Caputo, Caputo–Fabrizio, and Atangana–Baleanu senses. Yang and Liu [

26] carried out numerical study of fractional Burgers’-Huxley equations by utilizing a finite difference approach for time-fractional derivatives, and spatial direction was approximated by fourth-order compact approximation. A collocation technique based on extended cubic B-splines is proposed in [

27] for the numerical solution of the time-fractional Burgers’-Huxley equations. In this study, a

-weighted scheme is employed to approximate the temporal domain, while extended cubic splines are utilized to interpolate the derivatives along spatial direction. Furthermore, the stability as well as consistency of the approach are investigated.

Habiba et al. [

28] developed an improved Bernoulli sub-equation function approach for solving the generalized fractional-order Burgers’-Huxley equation by incorporating the definition of the conformable fractional derivative. Arifeen et al. [

29] implemented the Galerkin approximation to obtain the numerical solution of the fractional Burgers’-Huxley equation, in which the fractional operator is interpreted in terms of the Caputo sense. The study [

30] applied iterative approximations and energy estimates to explore the dynamic behaviour of the fractional stochastic Burgers’-Huxley equation under the influence of Levy noise and Brownian motion. Abali and Konuralp [

31] investigated the solution of Fredholm–Volterra fractional integro-differential equations utilizing a novel computational method based on shifted Gegenbauer wavelets. A matrix-based collocation approach is proposed in [

32] to compute the solution of second-order nonlinear ODEs governed by mixed boundary conditions. Khan et al. [

33] derived the numerical solution of parabolic differential equations subject to integral boundary conditions by employing the Haar wavelet-based collocation technique.

The present study provides a numerical solution to a Burgers’-Huxley model incorporating fractional derivative in temporal direction by using a B-spline-based collocation technique in combination with a finite-difference approach. The B-spline is a piecewise polynomial function that inherits smoothness conditions. One distinguishing feature of B-splines is that the resultant matrix for the discretized set of equations is sparse in nature due to its ability to deal with local occurrences. Furthermore, the method constructed by B-splines-based functions does not require any transformation to reduce non-linear differential equation into a simpler form, and as a result, numerical effort is reduced significantly. In order to attain optimal order of convergence along the spatial direction, the current study pertains to some posteriori changes in the second-order derivative of the cubic spline interpolant, leading to the formation of a modified technique.

The organization of the manuscript is as follows:

Section 2 is devoted to construction of a modified cubic polynomial basis by adding an extra term to Taylor’s series expansion for the second derivative. Implementation of the suggested technique in the proposed model, which has a fractional derivative in the temporal direction, is presented in

Section 3. Study of the stability and convergence criteria is included in

Section 4 and

Section 5, respectively. To prove the efficacy and applicability of the M43BS approach, five problems based on a fractional-order Burgers’-Huxley model are solved in

Section 6. The last section consists of overall conclusions.

3. Implementation of the Proposed Method

In order to discretize the fractional order derivative in temporal direction, this section presents the finite difference approximation. Assume step size in time for some positive integer

N defined by

with time instant

, for

respectively. By using Caputo’s formulation of derivative for

, an approximation of the temporal fractional-order derivative defined in Equation (

11) at time

is as follows [

37]:

Further simplification gives [

38]

where

,

and

. The coefficients

’s satisfy the following properties:

Integrating Equation (

1) by employing backward rectangular rule for the left-hand side and the source term and utilizing trapezoidal rule for the remaining terms together with Equation (

22) yields:

Using the following quasi-linearization procedure, the non-linear terms are linearized [

39]:

On rearranging the factors at various time levels, the following expression is produced:

At any

knot point, the resultant equation is

where

On substituting the computed values for function along with its derivatives of higher order at the specified knots and by clubbing the coefficients of time-dependent parameters , the corresponding equations are formed as follows:

For

where

For

:

where

For

where

In addition to the above, two more equations are derived using boundary conditions as

and

The matrix-form representation of the equations mentioned above is as follows:

where

and

In matrix

the first three elements of the first row and last three elements of the last row are (1,4,1), while the first six elements of the second row and final six elements of the second-to-last row are

and

, respectively. The remaining entries of the matrix are listed below:

The final system of equations attained is utilized for

By using this vector in Equation (

15), the required numerical solution at the

temporal level for

is obtained.

Initial Vector

In order to initiate the iterative procedure, the initial vector

needs to be specified to determine the solution for the succeeding temporal levels. For this, an initial condition is used at each knot point, i.e.,

=

. As a result, a system of (

) equations containing (

) unknowns will be obtained. To find a unique solution for this system, two additional conditions are employed, i.e.,

=

and

=

. Finally, the system of equations will result into a matrix of order

×

that can be represented as follows:

In matrix

the first three elements of the first row and last three elements of last row are (

,0,

). Remaining entries of the matrix are shown below:

Here,

denotes a column vector of order

×1 and

. The above system will be solved in order to determine the values of unknown time-dependent coefficients’

s at the initial time level. In this study, Matlab R2021a software has been utilized for performing numerical computations.

4. Stability Analysis

In order to determine the stability of the M43BS technique, the von Neumann approach is used. First, linearize the non-linear terms by assuming

=max

, and upon further employing the Crank–Nicolson approach in Equation (

1), the following expression is obtained:

On separating the terms at various time levels and assuming

, the above equation reduces to

Further, the above equation can be written as

where

. By substituting the approximate solution and its higher-order derivatives, the resulting expression is

After simplification, Equation (

32) takes the form

The above equation can be rewritten as follows:

where

Upon inserting the solution in single Fourier mode

=

in Equation (

34), where

is the size of amplitude,

denotes mode number,

h represents spatial step length and

=

, following equation is formed:

On simplification, the expression can be written as follows:

After inserting values of

’s, the above expression becomes

Based on stability criteria, the approach will be stable if the magnitude of is less than or equal to one for all k. By employing the principle of mathematical induction, it is observed that for varying values of parameters, i.e., , , h, and . This result demonstrates the unconditional stability of the approach.

6. Numerical Examples and Discussion

This section focuses on numerical solutions of generalized Burgers’-Huxley equations involving fractional operators. The method’s accuracy has been determined by utilizing Euclidean error norm

,

and maximum error norm

,

Here, exact and numerical values at knots

,

, are represented by variables

and

, respectively.

The order of convergence is calculated using the formula:

where

and

are the errors with

and

number of divisions along a spatial direction.

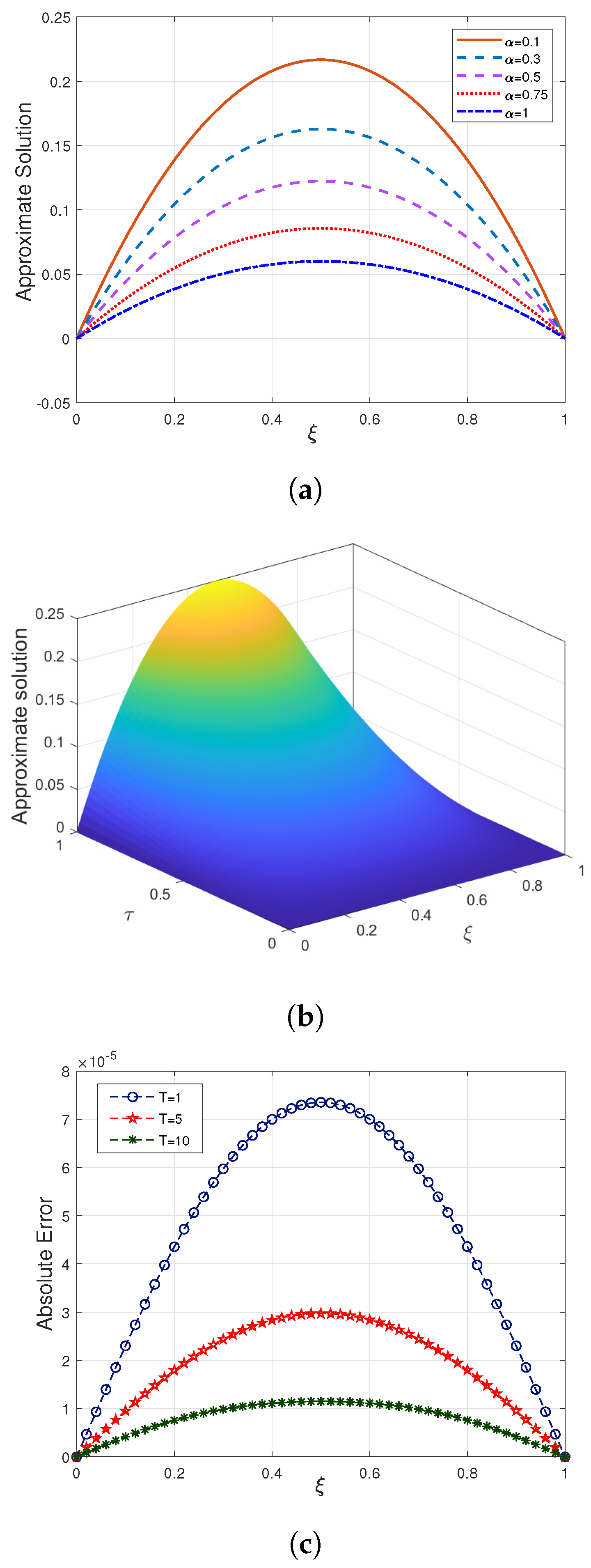

Example 1. Take TFBHE (8) together with the coefficients , , depending upon the initial conditionas well as the end conditionsThe source term isThe exact solution of the problem is given below [24]: Using parameters

,

,

, and

, error norms for Problem 1 are compared to those reported in [

24] for various values of temporal levels in

Table 1. The results indicate that the present approach is performing better as compared to the methodology described in [

24] for the same problem. For distinct choices of spatial partitions

M, the

as well as

error norms are presented in

Table 2, for

,

at temporal scale

. For different values of fractional order

and

, the absolute error is given in

Table 3. From

Table 2 and

Table 3, it is evident that the numerical solution rapidly converges to an exact solution, as the value of fractional parameter

approaches 1. In

Figure 1a, the solution is shown in two dimensions for distinct values of fractional order

by taking

,

, and

. The 3-D graphical surface representation of behaviour created by selecting

,

,

, and

is provided in

Figure 1b. In addition,

Figure 1c depicts the absolute error at different temporal scales by choosing

,

,

, and

. The figures and tables make it apparent that the proposed outcomes and actual results are congruent with each other.

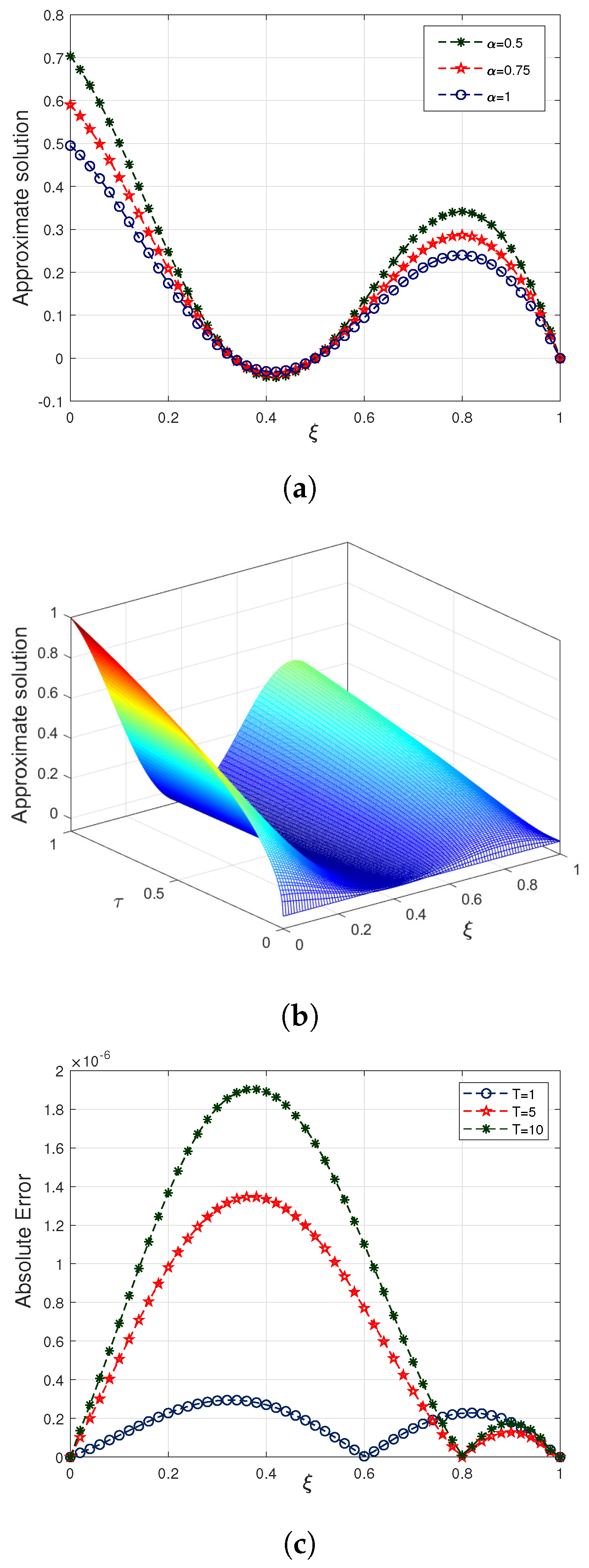

Example 2. In TFBHE (8), take the coefficients , and over spatial domain and temporal domain . The exact solution to this problem is as follows [24]:Here, the term is: The initial and boundary conditions are extracted from the exact solution provided above. When

,

Table 4 displays the error norms comparison with the results reported in [

24] at various time scales. The close agreement between the exact and numerical solutions can be observed from this table. By taking

,

,

Table 5 presents error norms for different numbers of divisions

M across the spatial domain. The error norms go on decreasing with increases in the number of spatial partitions

M.

Table 6 reports

and

error norms for various choices of

, taking into account

at time level

. It is evident from

Table 6 that, with decreasing temporal step size,

and

error norms go on decreasing. For

,

, and

, the 2-D surface behaviour of the suggested solution in the case of Example 2 at distinct values of fractional parameter

is shown in

Figure 2a, and the three-dimensional representation of the proposed solution for

is depicted in

Figure 2b. A 2-D plot for absolute error comparison at distinct temporal levels is displayed in

Figure 2c for the parameters

,

, and

. It is notable that the results obtained through present approach are in close agreement with the exact ones.

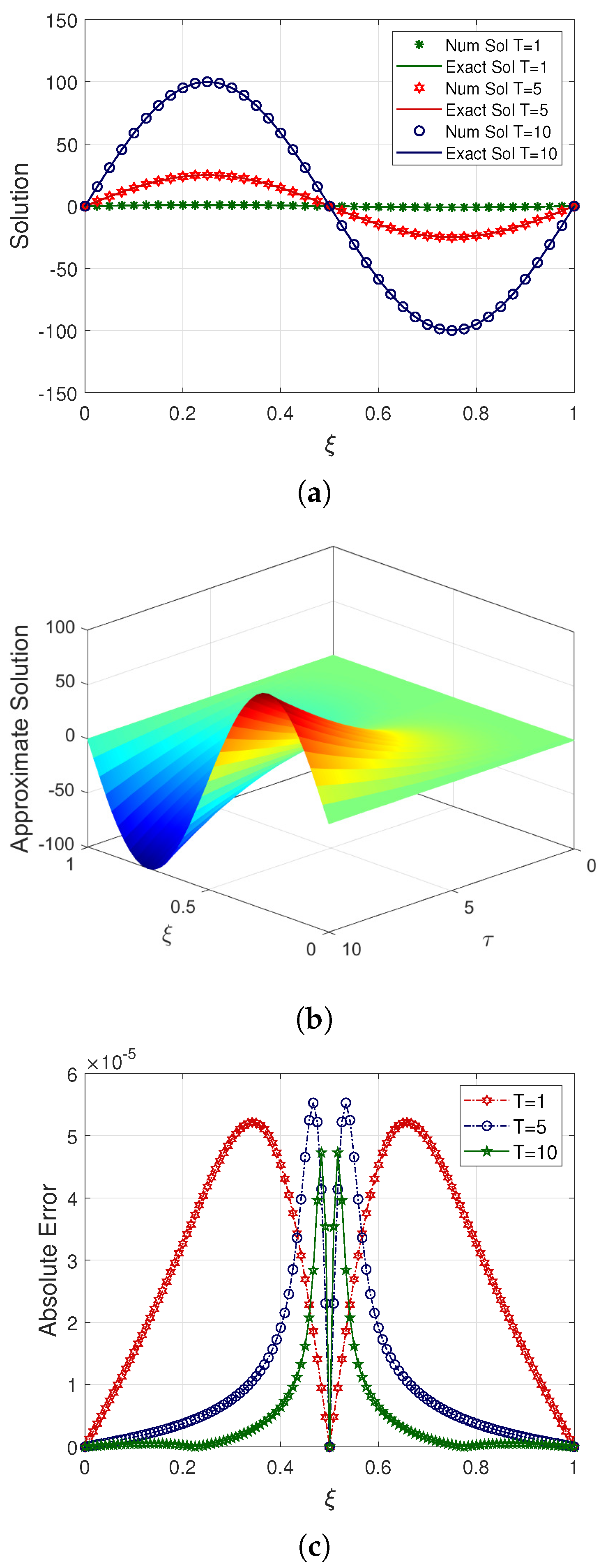

Example 3. Examine the non-linear Equation (6) for , and based on the initial conditiontogether with the end conditionsThe form of term isThe exact solution [41] of the problem is Table 7 provides the comparison of error norms for some choices of viscosity parameter

taking

,

, and

at time stage

, respectively. The order of convergence for spatial and temporal intervals is computed numerically in

Table 8 and

Table 9, respectively, showing the agreement between numerical and theoretical results. The numerical and the exact results for

,

, and

at different time levels are illustrated in

Figure 3a. The 3-D surface plot of the physical behaviour for

,

, and

is displayed in

Figure 3b. For

,

Figure 3c depicts the absolute error at various time stages.

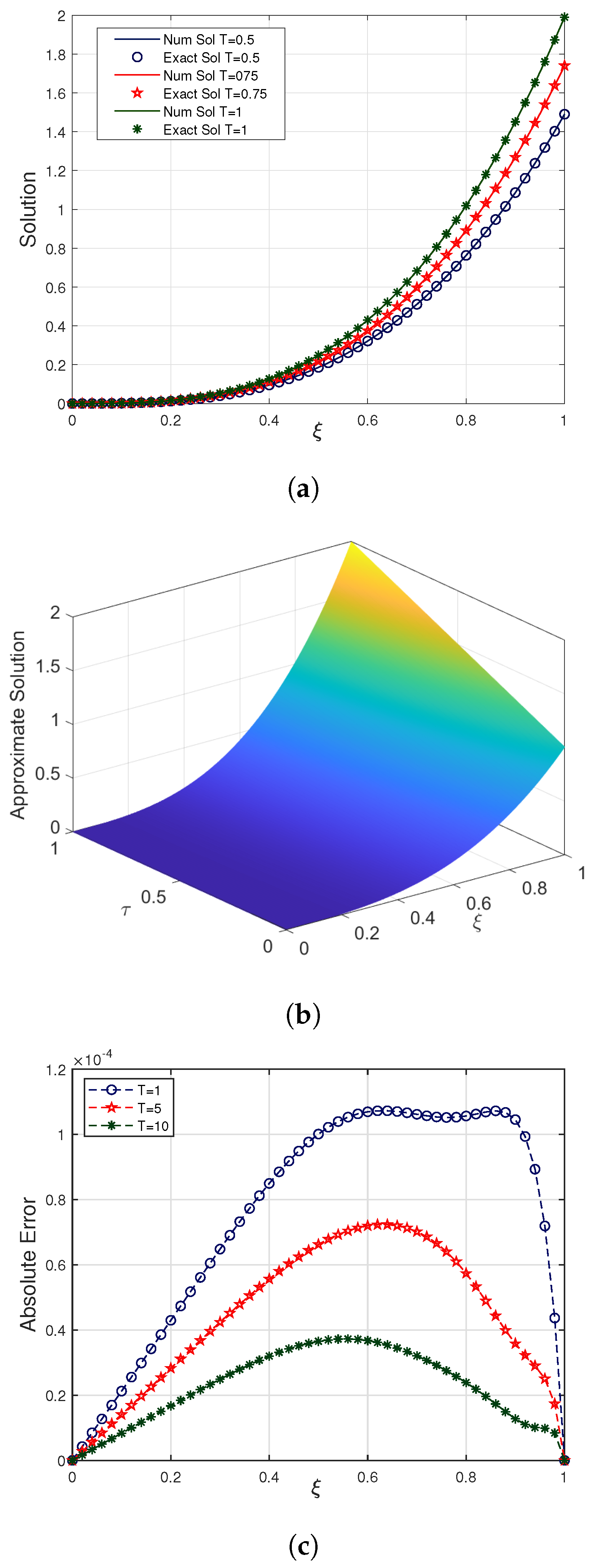

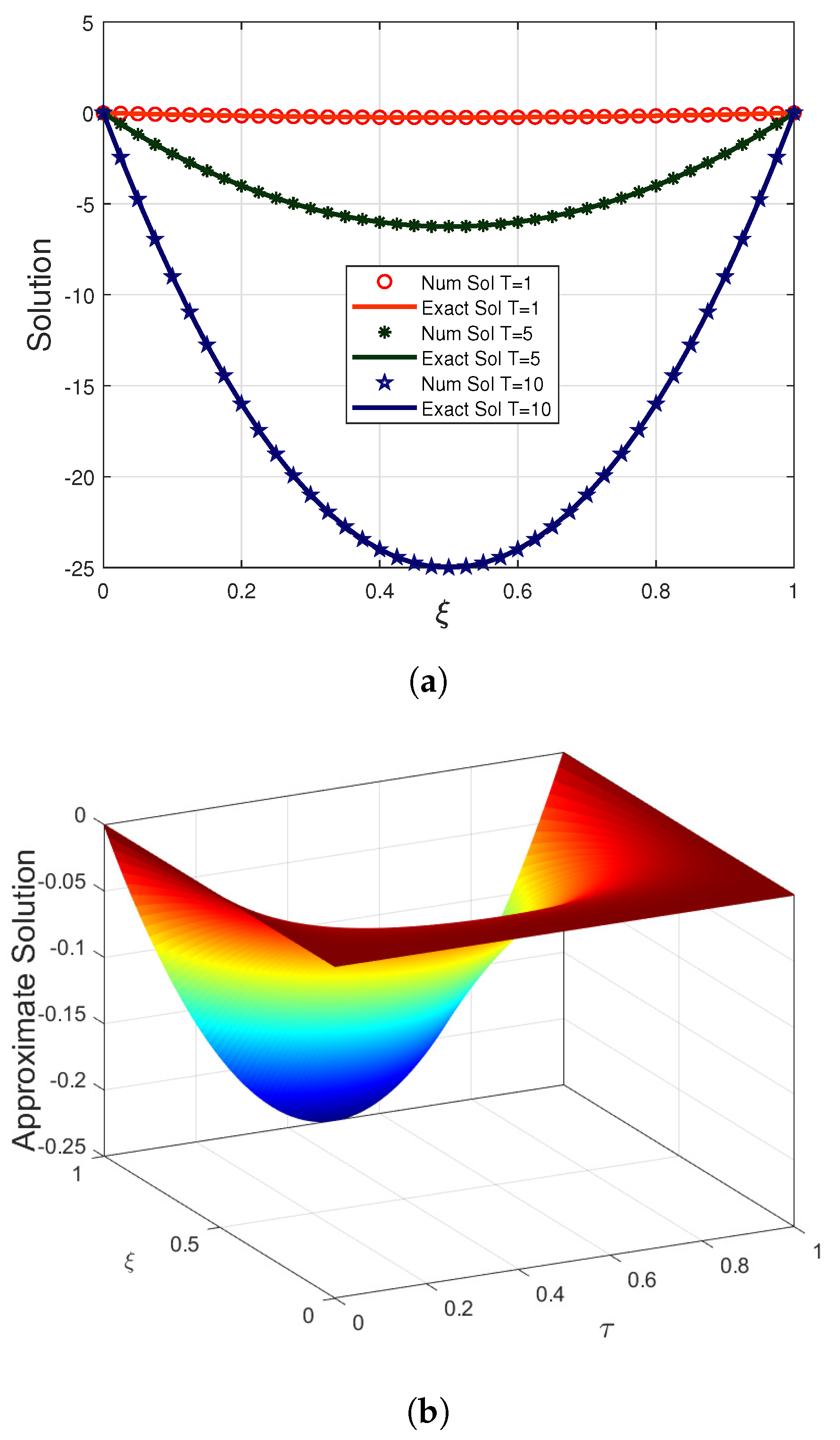

Example 4. Assume the coefficients , , and in Equation (8), and consider its resulting form depending upon the initial conditionin addition to boundary conditions asThe factor is written as follows:The exact solution [43] of the example is as follows: Table 10 reports Euclidean error norm

and maximum error norm

for Example 4 at distinct temporal levels by choosing

,

, and

d, respectively. For few choices of spatial divisions

M,

Table 11 provides the error norms for Example 4, taking into account

,

at temporal scale

, respectively. According to Table analysis, the decrease in

and

error norms is the result of an increase in the number of spatial divisions

M. Numerical comparison through absolute error across various knot points is shown in

Table 12 for different values of fractional order

, considering

,

, and

.

Table 12 reveals that increasing values of fractional order

contribute to a convergent solution. The result of utilizing various choices of time stages

T, overlapping of the exact solution with numerical values in case of Example 4, and considering

and

is illustrated in

Figure 4a. A 3-D graphical representation of the numerical solution for

,

,

, and

is shown in

Figure 4b. Furthermore, the absolute error profile resulting from taking

,

, and

is depicted in

Figure 4c. It is important to mention that the results achieved through the proposed methodology adequately capture the exact profile over the specified domain.

Example 5. Consider the generalized form of the fractional Burgers’ Equation (6) by assuming parameters , , and subject to the initial conditionand the boundary conditions asThe form of term isThe exact solution of the considered problem is given by [44]: The computation of

as well as

norms for

is reported in

Table 13, taking into account

,

, and

. From this table, it can be clearly observed that as the value of

approaches 1, the estimated solution tends to exactly one. The close similarity between the exact solution and estimated outcomes obtained by the proposed approach at distinct temporal scales is provided in

Figure 5a, taking

,

, and

. The graphical illustration of the proposed solution in three dimensions at

,

, and

is shown in

Figure 5b. Further, it is concluded that the exact findings and numerical outcomes of the proposed approach are compatible with each other.