Pathways Toward Carbon Peaking and Their Impacts on Industrial Structure in Hebei Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

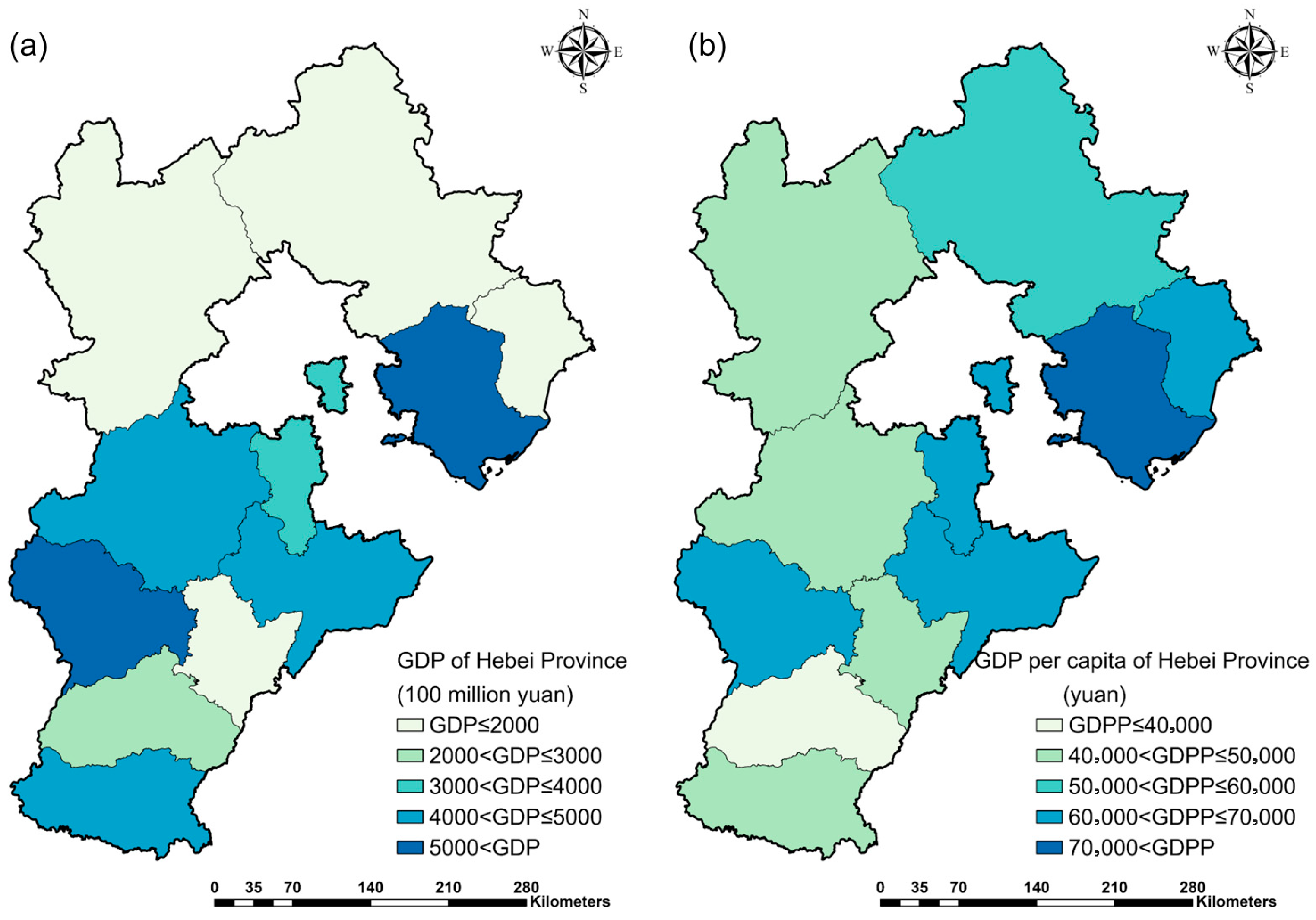

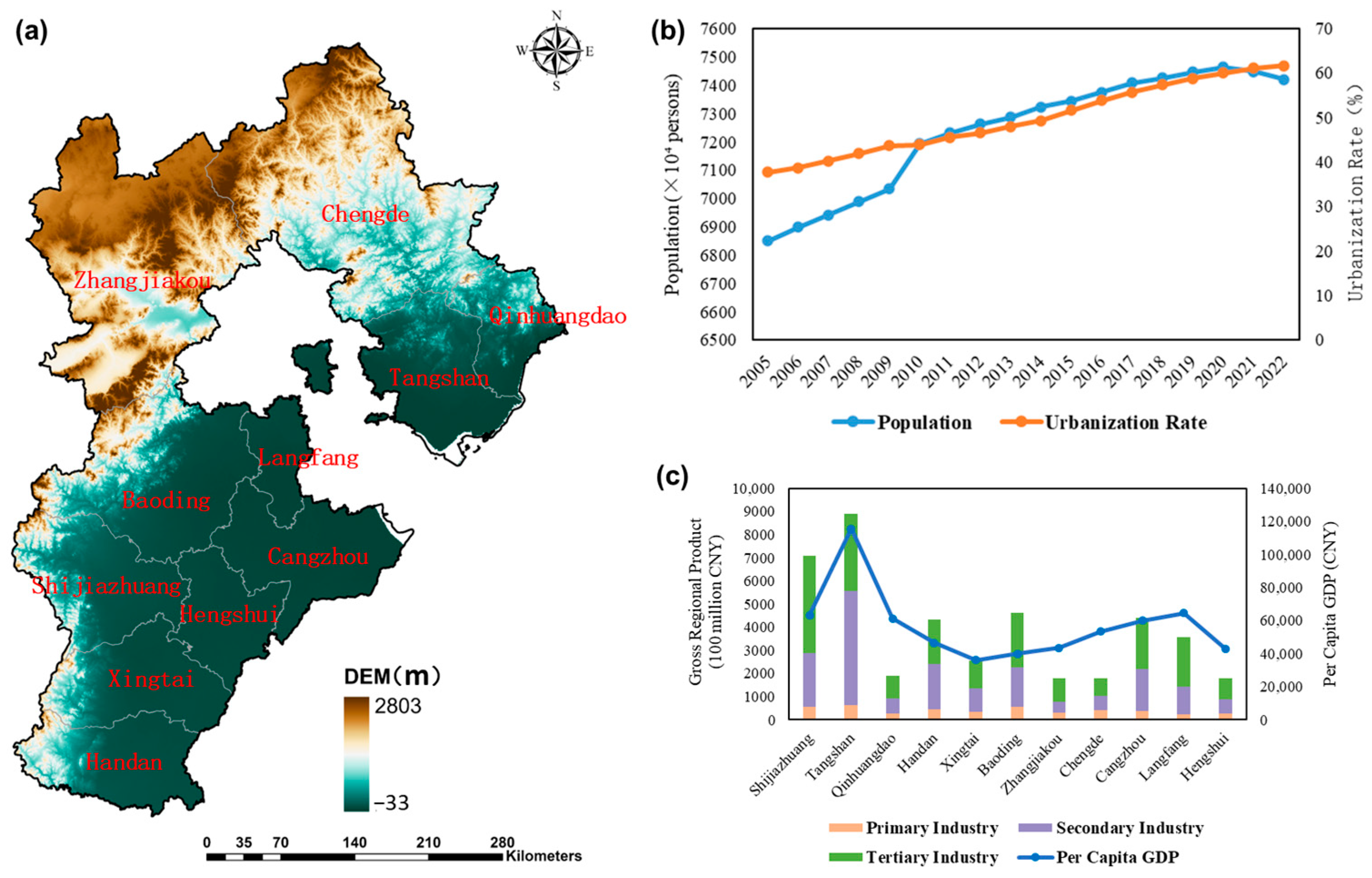

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Carbon Emission Accounting in Hebei Province

2.3. Carbon Emission Forecasting Model

2.4. Scenario Setting for Carbon Peaking Forecast

2.5. Data Sources

3. Results

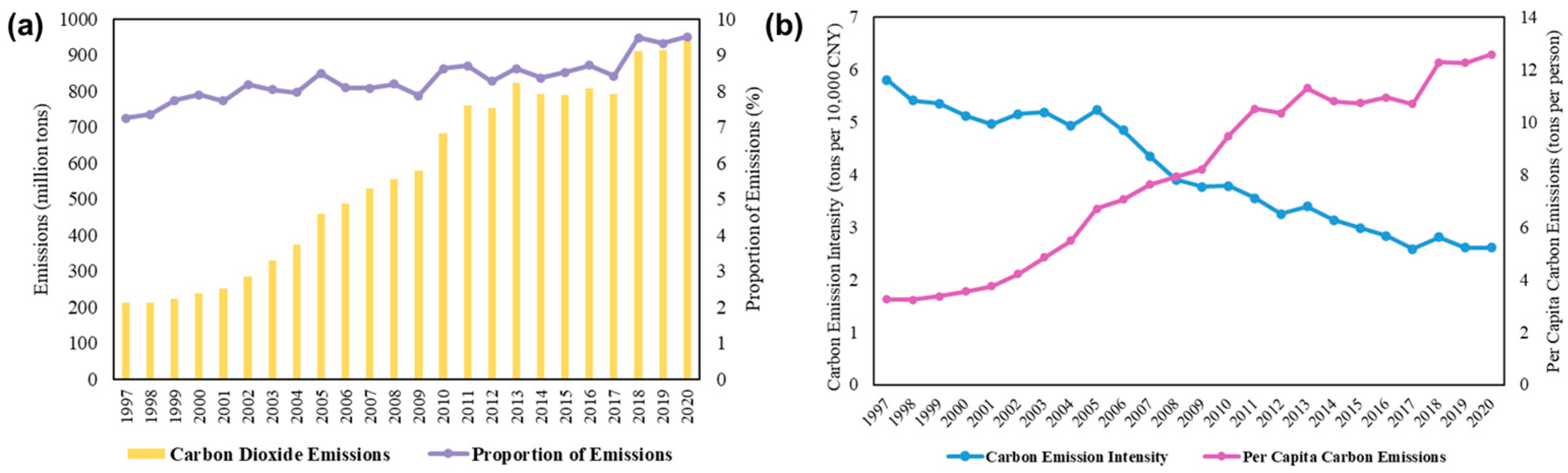

3.1. Characteristics of Carbon Emissions in Hebei Province

3.1.1. Basic Characteristics of Carbon Emissions

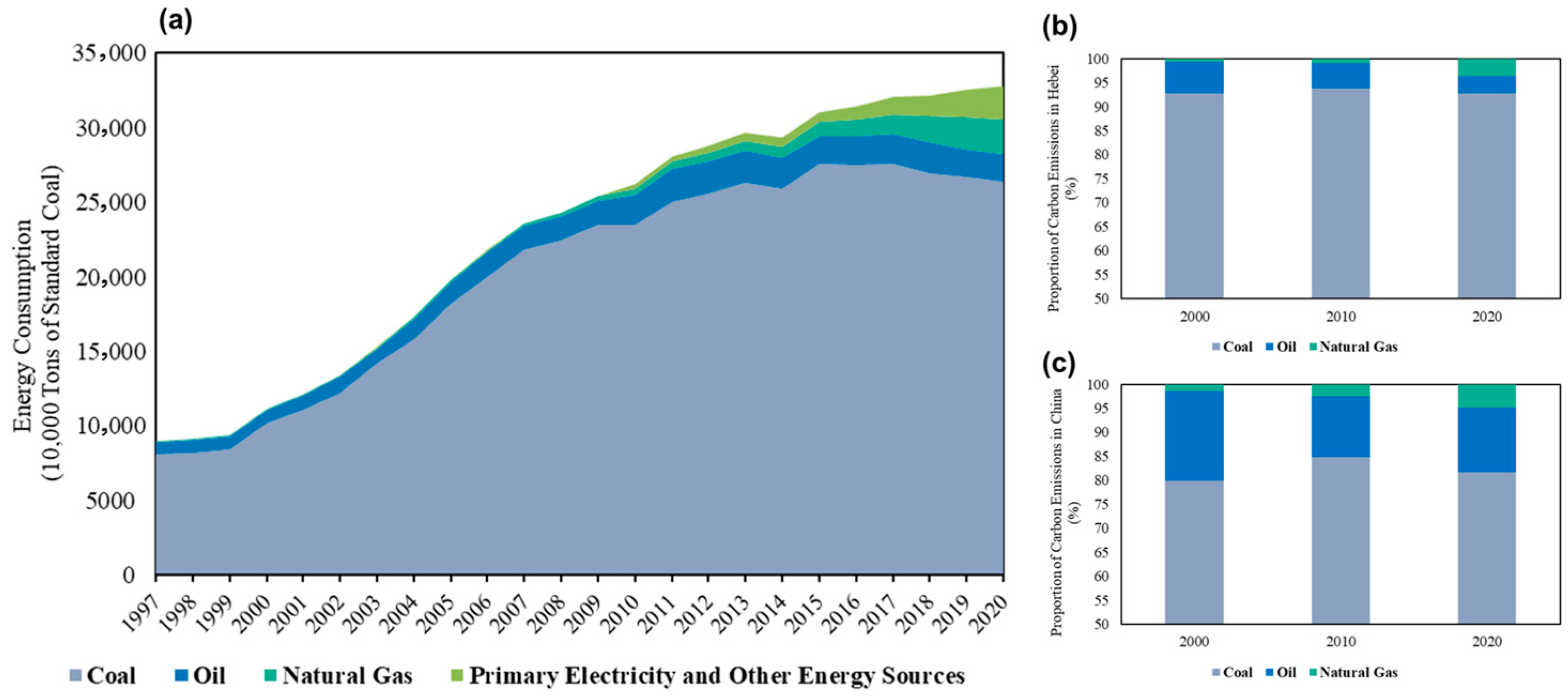

3.1.2. Energy Structure Characteristics of Carbon Emissions

3.1.3. Industrial Structure Characteristics of Carbon Emissions

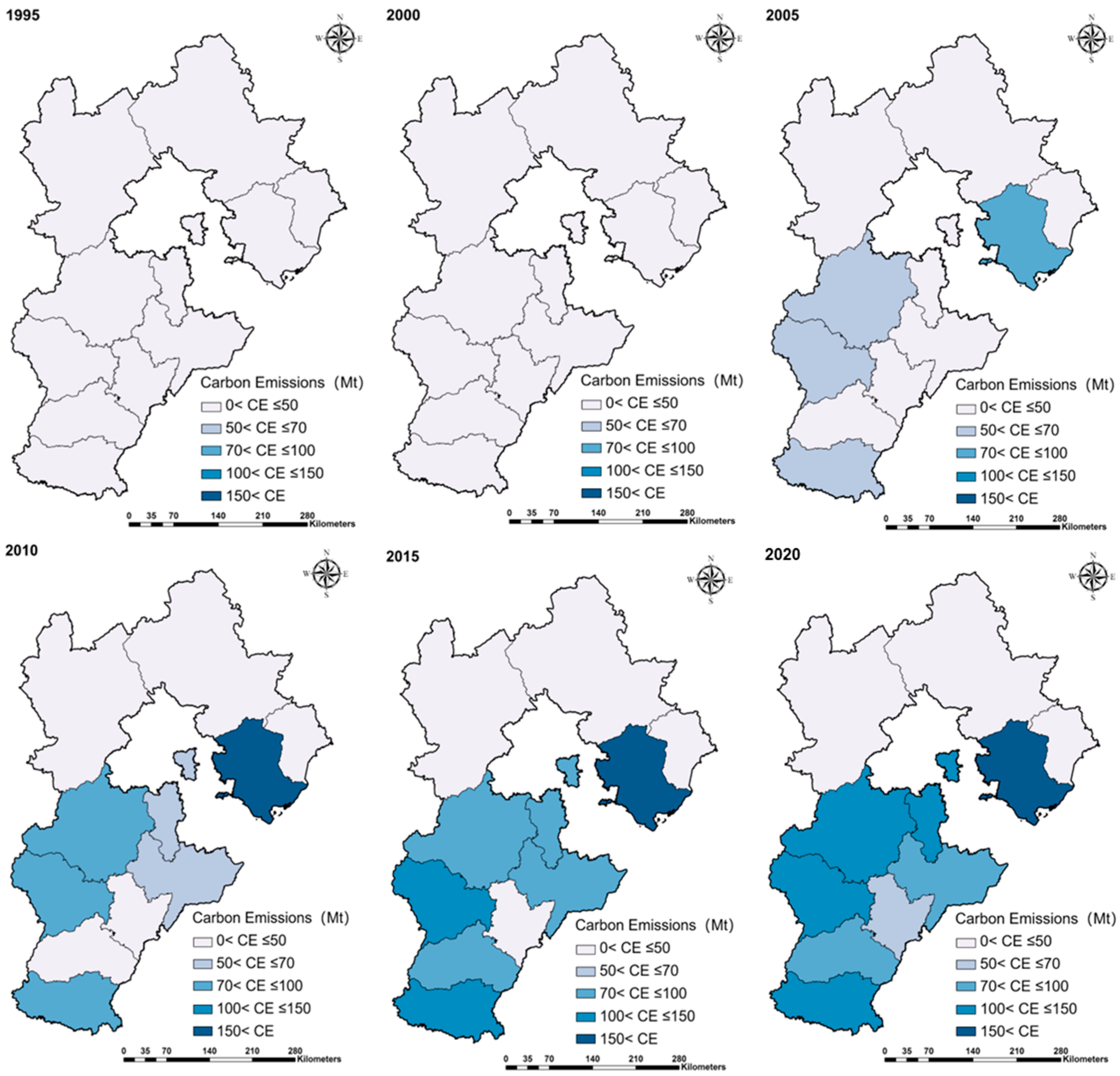

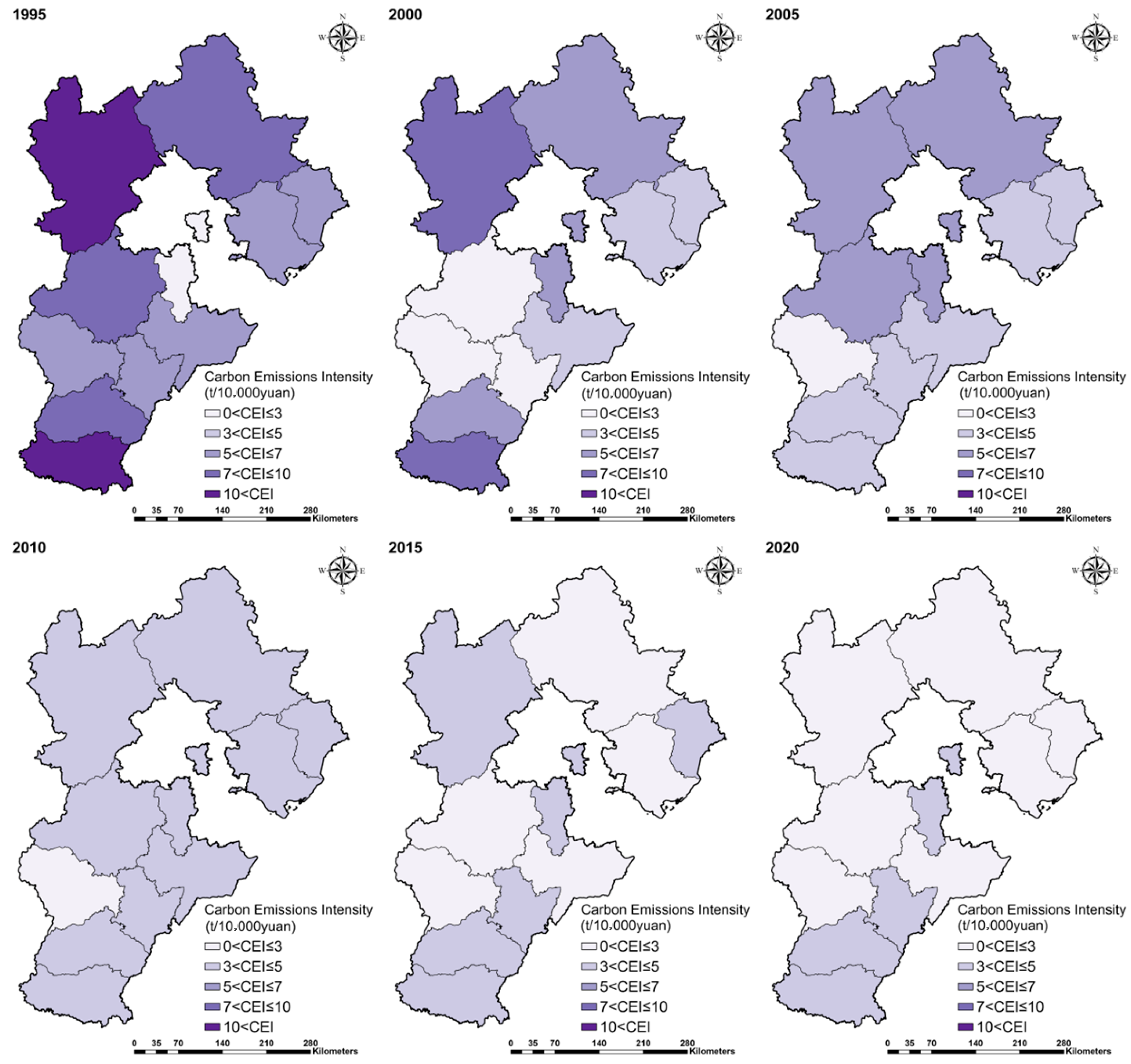

3.1.4. City-Level Characteristics of Carbon Emissions

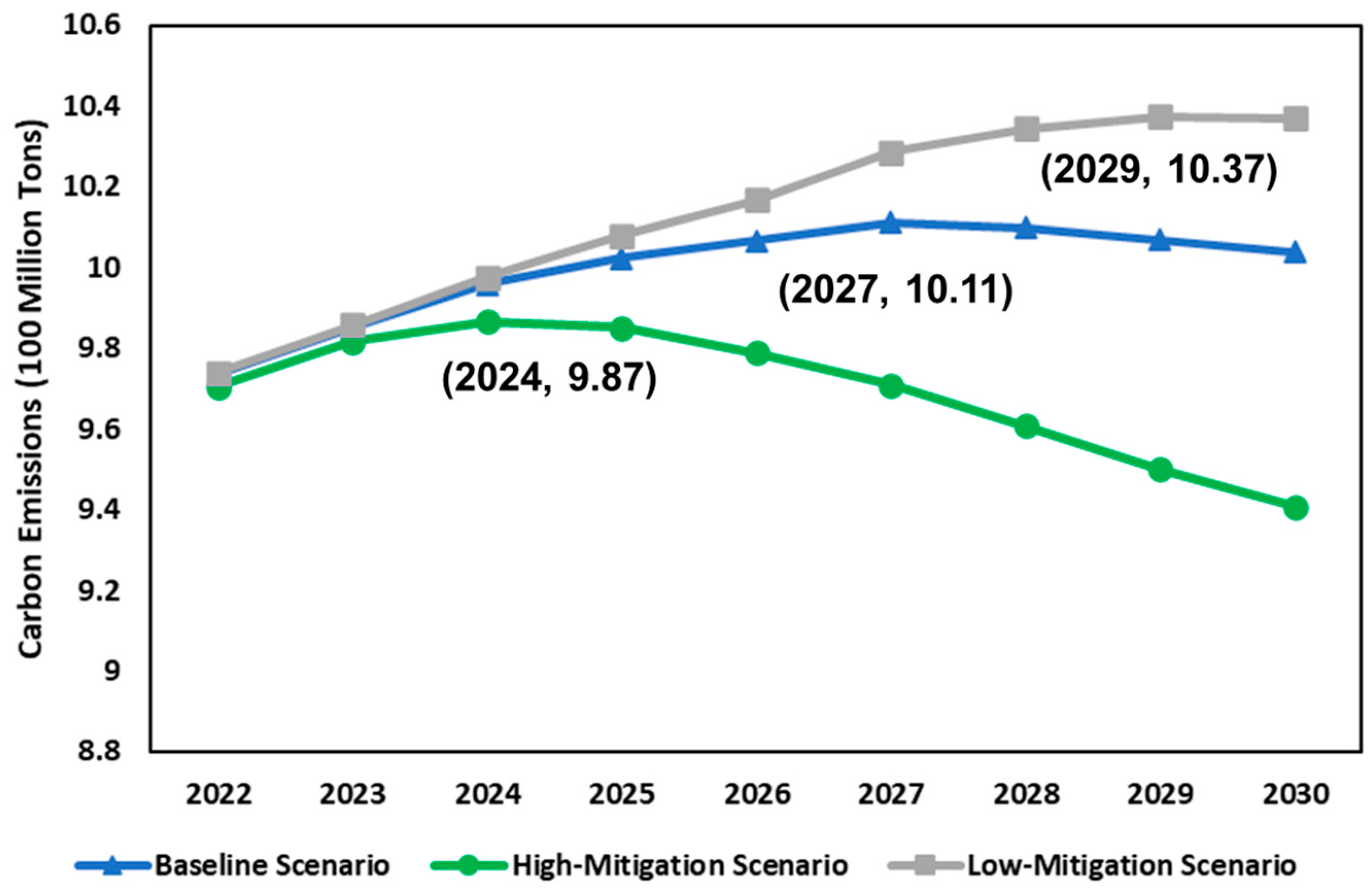

3.2. Scenario Projections for Hebei Province’s Carbon Peaking

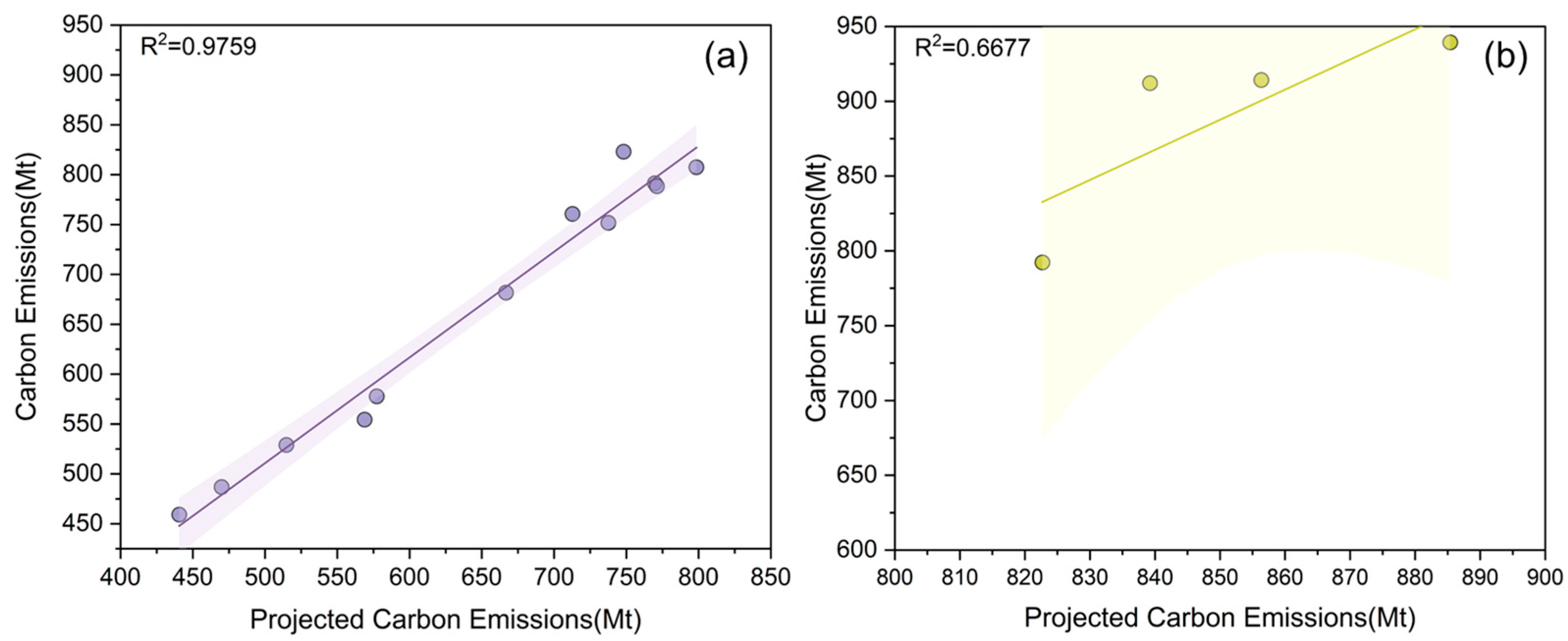

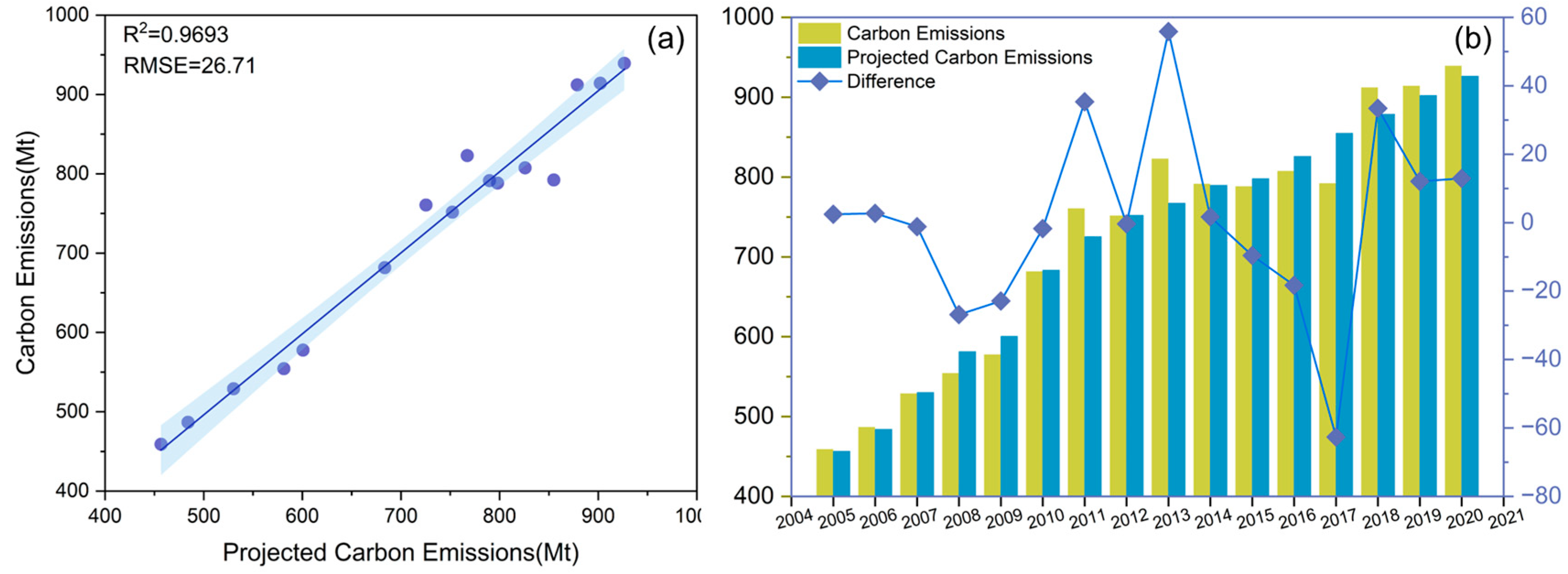

3.2.1. Carbon Emission Forecasting Model for Hebei Province

3.2.2. Results of Carbon Peaking Projections in Hebei Province

3.3. Industrial Structure Analysis Under Carbon Peaking Scenarios

- (1)

- Under the low-mitigation scenario, the share of the secondary industry is projected to fall to 34.71% by 2030. Based on the projected population and GDP per capita values (Table 2), the estimated gross output value of the secondary industry in 2030 will be approximately 2.035 trillion CNY, requiring the average annual growth rate to be limited to around 2.46%. Between 2017 and 2022, the secondary industry grew at an average annual rate of 6.55%, meaning its expansion must slow substantially. Since industrial sectors have consistently accounted for over 80% of the secondary industry’s output since 2005—with an average annual growth rate of 6.64% over the past five years—they remain the dominant drivers of industrial change. Consequently, controlling the growth of the secondary industry depends primarily on reducing the industrial sector’s expansion rate to approximately 2.4% per year, consistent with the required pace of deceleration.

- (2)

- The ferrous metal smelting and rolling industry has experienced substantial profit growth over the past five years, rising from 32 billion CNY to 84.2 billion CNY. Its share of total profits among large-scale industrial enterprises increased from 11.37% in 2016 to 34.30% in 2021, making it one of the main contributors to Hebei’s high carbon emissions. Since 2019, its value added has maintained an annual growth rate of about 6%, consistent with the overall industrial trend but far above the rate required for carbon peaking. As a key emission-intensive sector, its growth rate must be gradually reduced to below 2.4% annually under the low-mitigation scenario.

- (3)

- The electricity and heat production and supply sector is likewise a key target for emission reduction. On one hand, it involves lowering the share of thermal power generation; on the other, it requires controlling the overall pace of industry expansion. In recent years, the proportion of thermal power in Hebei Province has continued to decline, with an average annual reduction of more than 10%, consistent with the requirements of the low-mitigation scenario. However, in terms of total output, the sector’s value added has grown at an average annual rate of 4.53%. Production in energy-intensive industries within the province continues to depend on maintaining power generation capacity, and thermal power remains dominant. From 2015 to 2019, the installed capacity of thermal power generation increased from 435 GW to 502.1 GW, representing an average annual growth rate of 3.86%. Therefore, achieving the carbon-peaking target requires limiting the growth rate of the electricity and heat production sector to within 2.4% per year and gradually reducing thermal power capacity, transitioning from growth to stabilization and eventual decline before 2030.

- (4)

- Controlling the growth of the secondary industry and key subsectors will inevitably affect employment and enterprises. Since 2005, employment in the secondary industry first increased and then declined, with a sharp downward trend over the past five years. Under the low-mitigation pathway, the continued reduction in the secondary industry’s share is expected to result in a further decline in employment—by approximately 900,000 workers between 2023 and 2030. The number of employees and enterprises in the ferrous metal smelting and rolling industry has already decreased faster than projected under the low-mitigation scenario, aligning with carbon peaking requirements. In contrast, the electricity and heat production and supply industry has seen annual growth rates of 2.96% in employment and 21.71% in enterprise numbers over the past five years—both exceeding the limits set by the carbon peaking pathway. Under these constraints, the industry is projected to reduce employment by 3000 to 15,000 workers and the number of large-scale enterprises by 20 to 290 between 2023 and 2030.

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | β | F | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 0.085 | 0.758 | 71.46 |

| G | 0.021 | 0.079 | 331.28 |

| U | −31.14 | 0.017 | 139.00 |

| S | −13.817 | 0.282 | 44.01 |

| T | −1.117 | 0.825 | 107.66 |

| I | −150.18 | 0.384 | 116.88 |

| 1889.80 | 0.465 | / |

| Policy Basis | P | G | U | S | T | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 14th Five-Year Plan/ Hebei Province’s 14th Five-Year Plan/The 14th Five-Year Plan for the Modern Energy System/ The 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Renewable Energy | / | 7% * | 65% | 35.5% | 8% * | [−15%] |

| 2021–2025 annual average change rate | −0.3% * | 7% * | 2% * | −2.5% * | −8% * | −5.7% * |

| 2026–2030 annual average change rate | −0.4% * | 3% * | 2% * | −2.5% * | −5% * | −3% * |

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. CO2 Emissions. Our World in Data 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Grant, L.; Vanderkelen, I.; Gudmundsson, L.; Fischer, E.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Thiery, W. Global Emergence of Unprecedented Lifetime Exposure to Climate Extremes. Nature 2025, 637, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.J.; Mitchell, D.; Gibb, R.; Stuart-Smith, R.F.; Carleton, T.; Lavelle, T.E.; Lippi, C.A.; Lukas-Sithole, M.; North, M.A.; Ryan, S.J.; et al. Health Losses Attributed to Anthropogenic Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2025, 15, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.E.L. Attribution of Extreme Events to Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global Forecasts of Urban Expansion to 2030 and Direct Impacts on Biodiversity and Carbon Pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hejazi, M.I.; Wise, M.A.; Vernon, C.R.; Iyer, G.C.; Chen, W. Global Urban Growth between 1870 and 2100 from Integrated High-Resolution Mapped Data and Urban Dynamic Modeling. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. Impact of China’s New-Type Urbanization on Energy Intensity: A City-Level Analysis. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy; IEA: Paris, France. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Bai, Y.; Zheng, H.; Shan, Y.; Meng, J.; Li, Y. The Consumption-Based Carbon Emissions in the Jing-Jin-Ji Urban Agglomeration over China’s Economic Transition. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF002132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, J.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, W.; Gao, G.F.; Bi, Y. City-Level Emission Peak and Drivers in China. Innovation 2022, 3, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y.; An, K.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Du, P.; Meng, J.; Shan, Y.; et al. Heterogeneity in Carbon Footprint Trends and Trade-Induced Effects across China’s City Clusters. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guan, Y.; Oldfield, J.; Guan, D.; Shan, Y. China Carbon Emission Accounts 2020–2021. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Brief. Explainer: Why China’s Provinces Are So Important for Action on Climate Change. Carbon Brief 2022. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Yi, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhen, J.; Hu, H. Carbon Emission Drivers of China’s Power Sector and Its Transformation for Global Decarbonization Contribution. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Xu, M.; Doh Dinga, C. Long-term transformation in China’s steel sector for carbon capture and storage technology deployment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, F. Exploring the Role of Energy Transition in Shaping the CO2 Emissions Pattern in China’s Power Sector. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; You, K.; Cai, W.; Feng, W.; Li, R.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y. City-level building operation and end-use carbon emissions dataset from China for 2015–2020. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, D.; Guo, L.; Miao, C.; Zhang, D.; Yu, F.; Pan, W.; Li, F.; Peng, B.; Li, L.; et al. Downscaling Top-Down CO2 Emissions and Sinks in China empowered by hybrid training. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Baninla, Y.; Zhang, S.; Stenseth, N.C.; Hessen, D.O.; Tian, H.; Obersteiner, M.; Chen, D. Drivers of Change in China’s Energy-Related CO2 Emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Meng, J.; Reiner, D.M.; Zhang, N.; Shan, Y.; Mi, Z.; Shao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Davis, S.J. Structural Decline in China’s CO2 Emissions through Transitions in Industry and Energy Systems. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, X. Urban–Rural Carbon Emission Differences in China: Spatial Patterns and Driving Mechanisms. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 124567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yu, J. Determinants and Their Spatial Heterogeneity of Carbon Emissions in Resource-Based Cities, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Mi, Z.; Guan, D.; Zeng, N. Mitigation of China’s Carbon Neutrality to Global Warming. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, C.; Chen, X.; Jia, L.; Guo, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H. Carbon peak and carbon neutrality in China: Goals, implementation path and prospects. China Geology. 2021, 4, 720–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, M.; Dogan, E.; Taskin, D. A step forward on sustainability: The nexus of environmental responsibility, green technology, clean energy and green finance. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Deng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Nielsen, C.P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Bu, M.; Bi, J.; McElroy, M.B. China’s CO2 Peak before 2030 Implied from Characteristics and Growth of Cities. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Tian, C.; Li, X. Potential Pathways to Reach Energy-Related CO2 Emission Peak in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 66328–66345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Investigating the Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions in China: Promoting Transportation Industry as Carbon Peak Target. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.; Toledo, H. Renewable versus nonrenewable energy for Canada in a free trade agreement with China. Energy Econ. 2022, 105, 105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Cao, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Identifying the impacts of natural and human factors on ecosystem service in the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Jiang, Z.; Li, X. Provincial Carbon Emission Scenarios in China Based on GDIM and Structural Adjustment Pathways. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Modeling and Predicting City-Level CO2 Emissions Using Open Access Data and Machine Learning. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19260–19271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ding, L.; Gao, M. Carbon Emissions and Innovation Cities: A SHAP-Model-Based Study on Decoupling Trends and Policy Implications in Coastal China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Peng, S.; Liu, E. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Peak Prediction of Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions of Residential Buildings in China. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Li, S.; Rene, E.R.; Lun, X.; Zhang, P.; Ma, W. Prediction of Carbon Emissions Peak and Carbon Neutrality Based on Life Cycle CO2 Emissions in Megacity Building Sector: Dynamic Scenario Simulations of Beijing. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Liang, Q.; Wang, J.; Huo, T.; Gao, J.; You, K.; Cai, W. Dynamic Scenario Simulations of Phased Carbon Peaking in China’s Building Sector through 2030–2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Deng, Z.; Ma, X.; Xing, Y.; Pan, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tharaka, W.A.N.D.; Hua, T.; Shen, L. Analysis of the Synergistic Benefits of Typical Technologies for Pollution Reduction and Carbon Reduction in the Iron and Steel Industry in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qu, S.; Cai, B.; Liang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, M. Mapping Global Carbon Footprint in China. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Peng, D.; Li, T.; Liang, J.; Li, Y. The Impact of Rationalization and Upgrading of Industrial Structure on Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Driving Factors and Decoupling Effect of Energy-Related Carbon Emissions in Beijing. Sustainability 2024, 17, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Sun, C.; Li, Y. Does Industrial Transfer Change the Spatial Structure of CO2 Emissions? Evidence from the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region in China. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Z. Multi-objective green meal delivery routing problem based on a two-stage solution strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Diaz, D.F.; Wang, Y. Component-level modeling of solid oxide water electrolysis cell for clean hydrogen production. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 140940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Tong, R. Coal power demand and paths to peak carbon emissions in China: A provincial scenario analysis oriented by CO2-related health co-benefits. Energy 2023, 282, 128830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, Q.; Li, Y. Multi-process and multi-pollutant control technology for ultra-low emissions in the iron and steel industry. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 123, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Cui, F.; Xiang, N. Roadmap of Green Transformation for a Steel-Manufacturing intensive city in China driven by air pollution control. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, Y. City-level carbon emissions accounting and differentiation integrated nighttime light and city attributes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Jiang, J.; Li, C.; Miao, L.; Tang, J. Quantification and driving force analysis of provincial-level carbon emissions in China. Appl. Energy 2017, 198, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Yang, J.; Wu, F.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.; Li, X. Response characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emissions and land surface temperature in Guangdong Province, China. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Li, F. Examining the effects of urbanization and industrialization on carbon dioxide emission: Evidence from China’s provincial regions. Energy 2017, 125, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, B. Exploring the relationship between urbanization, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in different provinces of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Liu, T. Empirical analysis on the factors influencing national and regional carbon intensity in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, H. Do provincial energy policies and energy intensity targets help reduce CO2 emissions? Evidence from China. Energy 2022, 245, 123275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; He, Z.; Long, R. Factors that influence carbon emissions due to energy consumption in China: Decomposition analysis using LMDI. Appl. Energy 2014, 127, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Fang, Y.; Peng, S.; Benani, N.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Chai, Q.; Yang, P. Study on factors influencing carbon dioxide emissions and carbon peak heterogenous pathways in Chinese provinces. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassalle, G.; Fabre, S. Distinguishing carotene and xanthophyll contents in the leaves of riparian forest species by applying machine learning algorithms to field reflectance data. Adv. Remote Sens. For. Monit. 2022, 43–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hou, Z.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L.; Luo, J.; Shi, T.; Sun, W. Forecasting and Scenario Analysis of Carbon Emissions in Key Industries: A Case Study in Henan Province, China. Energies 2023, 16, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Pang, J. Analysis of Provincial CO2 Emission Peaking in China: Insights from Production and Consumption. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Long, D. Carbon Emission Forecasting and Scenario Analysis in Guangdong Province Based on Optimized Fast Learning Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, A.K.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, X.; Shao, C.Y.; Xiang, S. Pathway for China’s Provincial Carbon Emission Peak: A Case Study of the Jiangsu Province. Energy 2024, 298, 131417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yu, S.; Wu, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, L. Carbon Emissions Prediction Considering Environment Protection Investment of 30 Provinces in China. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Average Value | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 6851.00 | 7463.84 | 7217.44 | 52.08 |

| G | 12,845.00 | 48,564.00 | 31,089.00 | 2851.31 |

| U | 37.69 | 60.07 | 48.33 | 1.81 |

| S | 38.20 | 49.20 | 44.84 | 0.90 |

| T | 52.79 | 96.41 | 79.77 | 3.47 |

| I | 0.91 | 2.26 | 1.39 | 0.11 |

| Scenario | Variable | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Scenario | P | −0.20 | −0.20 | −0.20 | −0.30 | −0.30 | −0.30 | −0.40 | −0.40 |

| G | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| U | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| S | −5.00 | −5.00 | −5.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | |

| T | −5.00 | −5.00 | −5.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | |

| I | −5.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 | |

| High-Mitigation Scenario | P | −0.50 | −0.60 | −0.70 | −0.90 | −1.00 | −0.90 | −0.90 | −0.80 |

| G | 4.10 | 4.10 | 2.10 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| U | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1.20 | |

| S | −5.80 | −5.80 | −5.80 | −3.50 | −3.50 | −3.50 | −1.30 | −1.30 | |

| T | −8.00 | −8.00 | −8.00 | −6.00 | −6.00 | −6.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 | |

| I | −6.50 | −5.50 | −5.50 | −4.00 | −4.00 | −3.00 | −2.50 | −2.50 | |

| Low-Mitigation Scenario | P | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.20 |

| G | 6.00 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | |

| U | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | |

| S | −3.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | −1.50 | −1.50 | −1.50 | −0.50 | −0.50 | |

| T | −3.00 | −3.00 | −3.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | |

| I | −3.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 | −1.50 | −1.50 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 |

| Year | P (10,000 Persons) | G (CNY/Person) | U (%) | S (%) | T (%) | I (Tons of Standard Coal per 10,000 CNY) | Carbon Emissions (100 Million Tons) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Scenario | 2023 | 7420 | 56,995 | 61.65 | 40.20 | 43.23 | 0.82 | 9.73 |

| 2024 | 7405 | 59,845 | 62.88 | 38.19 | 41.06 | 0.78 | 9.85 | |

| 2025 | 7390 | 62,837 | 64.14 | 36.28 | 39.01 | 0.74 | 9.96 | |

| 2026 | 7375 | 64,722 | 65.42 | 34.47 | 37.06 | 0.71 | 10.02 | |

| 2027 | 7353 | 66,664 | 66.40 | 33.43 | 35.58 | 0.69 | 10.07 | |

| 2028 | 7331 | 68,664 | 67.40 | 32.43 | 34.15 | 0.67 | 10.11 | |

| 2029 | 7309 | 69,350 | 68.41 | 31.46 | 32.79 | 0.66 | 10.10 | |

| 2030 | 7280 | 70,044 | 69.44 | 31.14 | 31.80 | 0.65 | 10.07 | |

| High-Mitigation Scenario | 2023 | 7383 | 59,332 | 62.39 | 37.87 | 39.77 | 0.76 | 9.82 |

| 2024 | 7339 | 61,764 | 63.14 | 35.67 | 36.59 | 0.72 | 9.87 | |

| 2025 | 7287 | 63,061 | 63.90 | 33.60 | 33.66 | 0.68 | 9.85 | |

| 2026 | 7222 | 64,512 | 64.53 | 32.43 | 31.64 | 0.65 | 9.79 | |

| 2027 | 7149 | 65,996 | 65.18 | 31.29 | 29.74 | 0.63 | 9.71 | |

| 2028 | 7085 | 66,655 | 65.83 | 30.20 | 27.96 | 0.61 | 9.61 | |

| 2029 | 7021 | 67,322 | 66.62 | 29.80 | 26.84 | 0.59 | 9.50 | |

| 2030 | 6965 | 67,995 | 67.42 | 29.42 | 25.76 | 0.58 | 9.41 | |

| Low-Mitigation Scenario | 2023 | 7412 | 60,414.7 | 63.50 | 38.994 | 41.93 | 0.79 | 9.86 |

| 2024 | 7405 | 64,039 | 65.40 | 37.82 | 40.67 | 0.78 | 9.98 | |

| 2025 | 7398 | 67,241 | 67.37 | 36.69 | 39.45 | 0.76 | 10.08 | |

| 2026 | 7387 | 70,604 | 69.72 | 36.14 | 38.66 | 0.75 | 10.17 | |

| 2027 | 7375 | 74,840 | 72.16 | 35.60 | 37.89 | 0.74 | 10.29 | |

| 2028 | 7368 | 77,085 | 73.97 | 35.06 | 37.13 | 0.73 | 10.34 | |

| 2029 | 7361 | 78,627 | 75.82 | 34.89 | 36.76 | 0.72 | 10.37 | |

| 2030 | 7346 | 79,806 | 77.71 | 34.71 | 36.39 | 0.72 | 10.36 |

| Year | CEs with HMS P | CEs with HMS G | CEs with HMS S |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 979.608 | 983.162 | 984.705 |

| 2024 | 983.211 | 991.915 | 995.209 |

| 2025 | 980.757 | 996.243 | 1001.429 |

| 2026 | 974.511 | 998.818 | 1005.660 |

| 2027 | 966.699 | 1001.372 | 1009.974 |

| 2028 | 955.080 | 1000.015 | 1008.583 |

| 2029 | 943.620 | 996.901 | 1005.484 |

| 2030 | 933.946 | 993.744 | 1002.344 |

| Year | CEs with LMS P | CEs with LMS G | CEs with LMS S |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 986.869 | 987.155 | 985.927 |

| 2024 | 999.495 | 1000.304 | 997.546 |

| 2025 | 1007.796 | 1011.657 | 1004.781 |

| 2026 | 1014.880 | 1021.280 | 1009.692 |

| 2027 | 1022.023 | 1033.983 | 1014.649 |

| 2028 | 1024.341 | 1038.471 | 1013.868 |

| 2029 | 1026.676 | 1038.584 | 1011.005 |

| 2030 | 1027.142 | 1037.294 | 1008.097 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lou, S. Pathways Toward Carbon Peaking and Their Impacts on Industrial Structure in Hebei Province. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120516

Zhao Y, Zhou Y, Lou S. Pathways Toward Carbon Peaking and Their Impacts on Industrial Structure in Hebei Province. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120516

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, You, Yuan Zhou, and Shenghua Lou. 2025. "Pathways Toward Carbon Peaking and Their Impacts on Industrial Structure in Hebei Province" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120516

APA StyleZhao, Y., Zhou, Y., & Lou, S. (2025). Pathways Toward Carbon Peaking and Their Impacts on Industrial Structure in Hebei Province. Urban Science, 9(12), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120516