1. Introduction

“The truth is out there”. The infamous catchphrase from the television series “The X-Files”, which originally aired from 1993 to 2002 and had a revival from 2016 to 2018, featured a pair of FBI special agents who investigate unconventional, epistemic ways of interpreting reality, such as urban legends, ufology, the paranormal, and cryptozoology. However, unlike the themes mentioned above, conspiracy theories have a far greater potential to extend beyond the realm of fiction. They can shape the news, interfere with elections and public policies, challenge democratic regimes, fuel geopolitical disputes, and discredit scientific knowledge.

It is no wonder that this subject is receiving increasing attention, alongside related phenomena such as the contemporary epistemological crisis, the paradigm of post-truth, and the logic of disinformation. Consequently, the issue of conspiracy theories has proven to be a relevant cultural, social, and political subject, and its study, strategic and necessary, particularly in the context of defending Western democratic regimes.

In Brazil, the scientific investigation of this topic is still modest compared to other countries, but it began to gain traction following events and phenomena such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonarism, the spread of fake news, and the conservative discourse of the evangelical caucus in the National Congress. This gradual transition from neglect to dedication in the study of conspiracy theories is not only a recognition of the topic’s relevance but also a response by academia to the anti-democratic and anti-scientific appropriation of conspiracy narratives by extremist and radical movements.

In recent years, linked to the rise of Bolsonarism, the use of conspiracy theories by the far-right agenda has impacted various dimensions of Brazilian democracy. This ranged from a loss of trust in sanitary and scientific authorities during the pandemic crisis that began in 2020, passed through the alleged communist threat, and even culminated in advocacy for a return to the military dictatorship and the dissolution of the system of checks and balances among the three branches of government established by the 1988 Brazilian Constitution.

Given this scenario, this study consists of analyzing floor speeches by federal representatives from the Liberal Party (PL)—whose political leader is Jair Messias Bolsonaro—who were re-elected for the current legislative term from 2023 to 2027. The objective is to identify potential patterns and typical features of conspiracy theories within them (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The main academic hypothesis of this paper is the existence of a strong correlation between the Bolsonarist movement and the systematic adoption of conspiracy theories within the Brazilian political sphere.

To this end, this paper is structured in four parts: (1) a brief introduction to the concept of conspiracy theories; (2) a succinct discussion of the phenomenon of Bolsonarism; (3) a presentation of the research methods and techniques employed; and (4) an analysis of the floor speeches of Brazilian federal representatives from the PL from 2019 to 2024, focusing on their logic (epistemological elements) and rhetoric (narrative elements).

2. Conspiracy Theories

To conceptualize the term “conspiracy theories”, it is essential to recognize its two dimensions: the epistemological and the narrative (

Butter and Knight 2020, pp. 3–4). The former pertains to demands of knowledge, involving its logic and content, while the latter pertains to literary demands, encompassing its form, function, and context. Within this binary framework, for an account to be classified as a conspiracy theory, it must be two things. On one hand, it must be presented as a claim about some hidden power responsible for specific events or situations that, given its secret and non-falsifiable nature, is difficult to justify according to normally recognized standards of evidence (

Dyrendal et al. 2018). In other words, it constitutes a form of stigmatized knowledge. On the other hand, it must be a narrative and, as such, possess recurring stylistic elements and functions, playing the cultural role of forging identities and articulating conflicts (

Butter 2014, p. 21) by explaining the past and predicting the future through speculation (

Bratich 2008, p. 13).

It is important to highlight that the study of conspiracy theory addresses other elements beyond the conspiracy narrative itself, such as: the conspiracy theorist and their agents; the “consumer” of conspiracy theories; and contextual aspects of conspiracy theories (for example, conspiracy culture and a conspiracy mindset). Although these elements are present in this article, when they appear, it is always tangentially and in service of analyzing the conspiracy theory as a discourse in its epistemological and narrative dimensions.

Although the epistemological and narrative dimensions are interwoven into a single concept—in this case, “conspiracy theories”—a division between them is necessary for the didactic, systematic, and methodological purposes of this article. Therefore, the present section titled “Conspiracy Theories” has been divided into two subsections: one emphasizing the epistemological aspects and the other the narrative aspects of the concept in question.

2.1. The Epistemological Dimension: Conspiratorial Logic

Influenced by the seminal study The Paranoid Style in American Politics, published in 1965 by the American historian Richard Hofstadter (1916–1970), paranoid and generalist perspectives were employed for many decades to study conspiracy theories. These approaches considered such theories to be anti-scientific, delusional, and/or superstitious, attributing irrationality or cognitive failure to the individuals who believed in them (

Hofstadter 1965;

Popper 1974). The very use of the word “paranoia” signaled a disqualification of the concept, even though Hofstadter clarified that it was a rhetorical, not a psychiatric, use of the term (

Hofstadter 1965, p. 4). He described the paranoid style as a political pathology and an expression of a persecutory feeling that became systematized in the form of conspiracy theories (

Hofstadter 1965, pp. 4–6). For this reason, a great deal of research on conspiracy narratives was conducted from the perspective of debunking them or pointing them out as epistemically problematic.

A distancing from the perspective of conspiracy theories as paranoia or irrationality intensified at the turn of the millennium. The objective of these revisionist analyses was not to condemn conspiracy theories, but rather to understand the appeal of their popular manifestations, assessing their cultural significance and social role (

Butter and Knight 2020, p. 31). Many of these cultural studies drew on the ideas of the American literary critic Frederic Jameson (1934–2024) (

Jameson 1988), for whom conspiracy theories were symptoms of contemporary society’s inability to map the complex web of social, economic, and political realities in a globalized, postmodern world (

Butter and Knight 2020, p. 32). For him, conspiracy theories are not necessarily lunatic thinking but can constitute narratives of political contestation (

Butter and Knight 2020, pp. 32–33). They would be creative responses with sociopolitical value and ways of confronting problems related to power and secrecy in contemporary societies, which can bring important contributions to the study of issues related to authority, governance, and civic-political engagement, among other topics. In this context, conspiracy theories would be a form of “political propaganda” (

Cassam 2019, p. vii). Therefore, since the primary objective of conspiracy theories is to advance a political-ideological agenda through implausible accounts that can nonetheless influence public opinion, they “need to be understood first and foremost in political terms” and “the response to them also need[s] to be political” (

Cassam 2019, pp. vi–vii).

In an attempt to synthesize the epistemological dimension of conspiracy theories, we propose a set of six epistemic characteristics that define their logic. This characterization was systematized using the contributions of

Hofstadter (

1965),

Barkun (

2013), and

Cassam (

2019) as a starting point.

- (1)

Conspiracy theories are Manichean, as they explain reality through a dualistic view of the forces of good—the conspiracy theorist—against evil—the conspirators.

- (2)

Conspiracy theories are speculative, because they are based on conjecture rather than knowledge; they are grounded in suppositions rather than solid evidence.

- (3)

Conspiracy theories are populist, because they are founded on a critique of the elite and the glorification of popular sovereignty, with an emphasis on the belief in the deceptive nature of authorities—deceptive officialism (

Wood et al. 2012, p. 768).

- (4)

Conspiracy theories are science-mimetic, because they imitate the rhetoric and language of science, while simultaneously and proudly positioning themselves as stigmatized or counter-epistemic knowledge.

- (5)

Conspiracy theories are unconventional, as they do not shy away from improbable, implausible, or even bizarre explanations. They are generally contrary to the obvious explanations for events.

- (6)

Conspiracy theories possess a self-sealing nature; that is, contrary evidence is always treated as part of the conspiracy. In extreme cases, conspiracy theories are “particularly immune to challenge” and “invulnerable to contrary evidence” (

Sunstein and Vermeule 2009, pp. 3, 20).

2.2. The Narrative Dimension: Conspiratorial Rhetoric

The conspiracy account possesses its own stylistic elements and recurring functions, with a questioning and speculative focus (

Barkun 2013;

Bratich 2008). Taking into account the narrative dimension and the rhetorical manifestation of this “conspiratorial explanatory style” (

Byford 2011, p. 88), it is possible to identify an anatomy of conspiracy theories, composed of a triad of narrative elements, namely: (1) a conspiring group; (2) a conspiratorial plan; and (3) an effort to maintain secrecy (

Byford 2011, p. 71;

Cubitt 1989, p. 18). This triad stems from the definition that conspiracy theories are born from a belief “that an organization made up of individuals or groups was or is acting covertly to achieve some malevolent end” (

Barkun 2013, p. 3).

Regarding the first element of the triad, the conspiratorial group, two characterizations deserve emphasis: the identity and the character of the conspirators (

Byford 2011, p. 71). Identifying the conspirators is a paradoxical activity. While the conspirators must be clearly known in order to be combated, they must also, to a certain extent, remain hidden from public opinion, given the secret nature of their stratagems. A common solution to this dilemma has been to refer to the conspirators in vague and/or encompassing terms. This can involve using geographical locations or symbolic institutions such as “Wall Street”, “Big Pharma”, or “the Vatican”, or employing collective labels, such as “the Jews”, “communists”, “bankers”, etc.

The identity of the conspirators is also subject to what is termed “associative shift” (

Cubitt 1989, p. 23); that is, groups that originally do not belong to the conspiracy narrative can be associated with the conspirators, even if this identification is implausible. In this way, every Catholic can be treated as a Jesuit, or, furthermore, the phenomenon of German Nazism can be presented as having been a movement of the Left.

This associative rhetoric reinforces another important characteristic of the conspirators: their character or nature. Conspirators are frequently designated as perfect models of malice, a kind of amoral supermen (

Hofstadter 1965, p. 31). It is common to attribute them religious designations with a profane meaning, such as monsters, Satan, the Antichrist, among others. However, the most ubiquitous characteristic that conspiracy theories ascribe to them is an elite status (

Byford 2011, p. 76).

The villainous conspirators are located in the upper echelons of universities, the business world, the political arena, and religious institutions. The conspirators’ alleged privileged position is what lends consistency to the accounts of their control over education, the economy, technology, and/or international politics. Thus, there is an immanently subversive and populist nature to conspiracy narratives. They question elites, powers, and authorities, often through persecutory emphasis, informational tumult, and speculative chaos.

The second element of the triad, the conspiratorial plan, is always cloaked in grandiosity. It is a plot that will decide a nation’s future, a scheme that could alter the course of world history, or a hidden power that places the very existence of humanity at risk. In contemporary conspiracy culture, the most famous plan behind a conspiracy is the establishment of a “New World Order” (

Byford 2011, p. 77). Present in conspiracy discourses since the 1960s, this term became popular after its use by former U.S. President George Bush in a 1991 speech. That same year, this impactful episode was reinforced by the publication of the conspiracy best-seller The New World Order by Baptist pastor and religious media magnate Pat Robertson (

Goldberg 2001). Thus, the New World Order replaced the “communist threat” as the primary object of conspiracy narratives in the Western context. Furthermore, the New World Order created space for “ecumenical” conspiracy theories: the concept is sufficiently broad to house conspiracy theorists from the left and the right, and from religious and secular organizations (

Byford 2011, p. 78).

For the third element of the conspiracy theory triad—the effort to maintain secrecy—two points stand out. Firstly, this element is essential to a conspiracy theory because it sustains the idea that social and political reality is more than it appears to be and, therefore, that there is something for the conspiracy theory to explain and reveal (

Hofstadter 1965, pp. 29–30). Secondly, it is the apparent secrecy of the plan that underpins the conspiracy theory’s irrefutable logic: since the conspirators are so competent at hiding evidence and manipulating reality, the absence of proof for the conspiracy can be taken as unquestionable evidence of its very existence (

Byford 2011, p. 79).

Paradoxically, conspiracy narratives also engage in a simultaneous and contrary movement. They employ a scientific rhetoric to present proof for their formulated conjectures. Conspiracy theorists see themselves as experts and researchers operating outside the scientific mainstream, and for this reason, the conspiratorial discursive style requires detailed expositions of plausibility and verifiable historical records. It is a mimesis of science.

Based on their epistemic logic and narrative structure, the study of conspiracy theories leads us to accept the premise that these rhetorics are not merely speculative or paranoid accounts, but rather expressions, interpretive patterns, and rhetorical tropes of a particular worldview, seeking to defend and promote political-ideological agendas (

Cassam 2019, p. 100;

Byford 2011, pp. 148–49).

2.3. Synthesis of the Dimensions: Conspiracy Theories as Worldviews

Taking into account the epistemological dimension of conspiracy theories (their logic and epistemic characteristics) and their narrative dimension (the literary elements of conspirator, plan, and secrecy), we conclude that the study of conspiracy theories leads us to accept the premise that these narratives are not merely cognitively problematic speculative accounts, but rather, above all, expressions of a particular worldview (

Cassam 2019, p. 100). It is no wonder they are also defined as “conspiracy myth” (

Cubitt 1989, p. 24) or a “mirror of the age” (

Nicolas 2016, p. 255). In any case, the essence of conspiracy theories lies in their attempt to make sense of evil, the result of which is a worldview predicated on an irreconcilable separation between good and malevolence.

It is in response to these premises and assumptions that conspiratorial logic and rhetoric are constructed, giving vent to the existential, social, and political dilemmas experienced from generation to generation. It is a resource that ultimately seeks to bring order and a sense of agency to the complexity and unpredictability of life in contemporary society. Indeed, past and present conspiracy theories are best understood “as a set of motifs, claims, patterns of interpretation and rhetorical tropes that people can dabble in, draw upon, modify and propagate as they make sense of the world, individually and collectively” (

Byford 2011, pp. 148–49).

3. Bolsonarism

The second key concept of this text—Bolsonarism—refers to a complex and multifaceted sociopolitical phenomenon. Its genesis is dated to 2013, when the largest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history up to that point erupted at Petrobrás, the state-owned energy company (

Rocha 2023).

Following the approach taken in the previous section in our treatment of the concept of conspiracy theories, and for the same didactic and methodological purposes, this article divides the concept of Bolsonarism into two dimensions: epistemological (logic) and narrative (rhetoric).

3.1. The Epistemological Dimension: The Logic of Bolsonarism

From an epistemological perspective, Bolsonarism can be viewed as a broad and heterogeneous neoconservative populist and authoritarian movement with a reactionary bent (

Duarte 2022;

Wajner and Wehner 2023). Its logic is constructed upon a popular sentiment of anti-leftism or anti-Petism

1 (

Solano 2020), originating from corruption scandals and the ideology of the communist threat.

Indeed, the Lula and Dilma Rousseff administrations were plagued by successive corruption scandals. In 2005, the first allegations of bribery payments to congressmen by the federal Executive Branch to influence legislative votes came to light, a case known as

Mensalão. In 2014, the famous

Lava Jato scandal erupted, involving systematic overpricing and embezzlement of funds from contracts awarded by the state-owned company Petrobras. Significant corruption cases like these provide favorable conditions for the emergence of populist leaders, “since they make it easier to depict the mainstream political establishment as both morally and financially corrupt” (

Zanotti et al. 2023, p. 13). Bolsonaro’s success in the 2018 general elections was largely due to his effective political capitalization of widespread voter frustration with corruption cases in the PT governments while simultaneously positioning himself as the central figure to combat old politics and the established traditional party system (

Zanotti et al. 2023, p. 18).

Bolsonaro is considered a far-right populist leader, belonging to the fourth wave of populism in Latin America (

Wajner and Wehner 2023, p. 10). The first wave (classic populism) came with Getúlio Vargas in Brazil and Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina between the 1930s and the 1960s. The second wave (neo-liberal neo-populists) was led by Carlos Menem in Argentina and Alberto Fujimori in Peru between the 1980s and the 1990s. Finally, the third wave (progressive neo-populists), initiated at the end of the 1990s by Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, followed by Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador during the beginning of the 21st century (

Farias et al. 2024, p. 2012;

Zanotti et al. 2023, pp. 2–3). From left to right, Latin America is a vast laboratory for populist governments of all political and ideological stripes (

Farias et al. 2024, p. 2005).

A notable characteristic of the fourth wave of far-right populism is that it belongs “to an interconnected global movement in which key thinkers have, over several decades, theorized and strategically mobilized cultural resentments, and developed a coherent sociological critique of globalization” (

Guimarães and Silva 2021, p. 349). Some authors even defend the existence of a populist international order, guided by three normative pillars: a preference for small-scale multilateral arrangements (minilateralism); a selective adoption of the international order’s norms (only insofar as it would be compatible with the popular will); and a view strongly opposed to pluralism of values, as a basic guideline for affirming the discourse of national sovereignty (

Farias et al. 2024, p. 2021).

The backbone of this conservative identity of far-right populism lies in three main concepts: anti-globalism, with a strong tendency towards aversion to international agencies; patriotism, centered on the idea of national sovereignty; and anti-enemy discourse, based on the “us versus them” narrative (

Guimarães and Silva 2021, pp. 345–46). Thus, from the perspective of far-right populist leaders, international and multilateral organizations represent a grand globalist and multiculturalist conspiracy that threatens national sovereignty and undermines the will of the people (

Guimarães and Silva 2021, p. 350).

It is common for the far-right populist leaders to talk about the existence of a conspiracy, whether external—led by multilateral foreign organizations—or internal—carried out by domestic enemies, such as the communists. This type of strategic discourse, which fosters division among the population around the idea of “us versus them”, manufactures enemies that support the narrative of restoring national sovereignty and the full popular will, allowing the populist leader to present himself as the only solution to provide security to the nation, in the face of the risks of disorder and chaos that his conspiratorial narrative aims to incite in the feelings of voters (

Giurlando and Wajner 2023, p. 2;

Guimarães and Silva 2021, pp. 350–51;

Motta 2025;

Woods 2025).

The operational logic of the Bolsonarist movement also involves the exploitation of feelings of fear and insecurity in the face of a supposed threat to traditional family and Christian values, through the manipulation of popular resentment toward the status quo (

Silveira and Amaral 2023). Consequently, Bolsonarism promotes a moralized attitude towards politics (

Lellis and Dutra 2020;

Duarte 2022). Its content is dictated by the paradigm of the “culture war”—a matrix for producing polarizing narratives whose radicalization around conservative social values engenders imaginary enemies—and by the principles of economic liberalism (

Schargel 2022;

Rocha 2023). In its attempt to interpret economic crises as moral tragedies and as the abandonment of traditional values, Bolsonarism establishes religion as the moral legitimizer and regulator of social life (

Solano 2020).

Thus, the Bolsonarist movement invokes Judeo-Christian values as one of the identity pillars aimed at recruiting and mobilizing its political base, to which it adds elements of patriotism and nationalism. These elements largely reflect a trend to Americanize the Brazilian Right and are inspired by Donald Trump (

Casarões 2022). Consequently, in Bolsonarism, the moralization of politics culminates in the Christianization of politics, strategically engaging a large portion of the Brazilian evangelical population (

Alexandre 2020;

Solano 2020).

By blending moralism and theocracy, while advocating for a meritocratic model based on Prosperity Theology, and embracing Evangelical anti-intellectualism, Bolsonarism is also understood as a movement with a religious bias (

Feltran 2020;

Solano 2020) or even as a form of civil religion (

Martins 2021). Its belief system was heavily influenced by the Brazilian writer Olavo de Carvalho, whose conspiracy theories, pseudoscientific arguments, and eccentric analyses of Western civilization prompted the creation of the label “Bolsolavism” (

Rocha 2023).

This politico-religious matrix makes Bolsonarism a fertile platform for conspiracist, denialist, and sectarian logic, resulting in a “collective cognitive dissonance” among its adherents—that is, “the creation of an alternative world, an authentic parallel reality whose delusions are taken as absolute truth” (

Rocha 2023, p. 37). For these reasons, the religious-sectarian traits of the Bolsonarist movement lead it to be identified as neofascist (

Boito 2022) and a “far-right fanatic mass-movement” (

Duarte 2022, p. 78).

Bolsonarism is also characterized by its strong opposition to progressive public policies, such as those dealing, for example, with racial quotas for university admission and the promotion of rights for the LGBTQIA+ community (

de Castro 2019;

Rennó 2022). On the other hand, the movement under study embraces projects that reinforce individual rights and guarantees, such as property rights, freedom of expression, and social prosperity based on neoliberal economic programs and the idea of meritocracy (

Dutra and Lima 2023).

The concept of authority is a cornerstone of Bolsonarism, manifesting as a deep reverence for military culture and rigid power hierarchies, both political and familial. This fixation on authority is closely linked to phallocentrism and “projections of masculine virility, symbolized in the figure of the former president” (

Checchia et al. 2023, p. 71).

Summarizing, the descriptions and definitions given above reveal a strong alignment between elements of the epistemological dimension of conspiracy theories and those of the epistemological dimension of Bolsonarism. First, Bolsonarism presents a Manichean reading of reality, in which good—represented by the right, neoliberalism, or Bolsonaro himself, among other possible examples—fights against evil, typified by the left, Petism, the “system”, or the figure of Lula. This Manichaeism is also expressed in a populist view where the anti-elite attitude is replaced in Bolsonarism by an anti-system or anti-mainstream stance. Second, there is some kind of elective affinity between conspiracism and Bolsonarism, insofar as the religious-sectarian nature of the movement is fertile ground for conspiracy theories, denialist discourses, and fake news. Third, it is apparent that Bolsonarist logic and conspiracy theories share the same epistemic irrationality, since their self-sealing nature results in a belief system that is immune to disproof, contradictory evidence, and criticism. This makes their narratives potentially speculative and unconventional, even as they attempt a mimesis of science—which is essentially the case with Bolsolavism.

3.2. The Narrative Dimension: Bolsonarist Rhetoric

From a narrative perspective, the phenomenon of Bolsonarism exhibits certain peculiarities in its form and style. Corruption is at the heart of the Bolsonarist discourse. The figure of its leader, Jair Bolsonaro, is presented as a simple, honest, and authentic man who thinks and speaks like the common people. This charismatic portrayal is combined with an aggressive anti-institutional rhetoric, used as a mechanism to confront the decadent and corrupt institutions of the contemporary political landscape (

Solano 2020;

de Sousa et al. 2024). Bolsonaro is seen as an anti-mainstream figure, since traditional parties are perceived as incapable of changing the Brazilian State bureaucracy and the representation system. For this reason, Bolsonarist rhetoric articulates the following binary:

old and traditional party politicians versus the

new and clean Bolsonaro, called “the Myth” (

o Mito) by his voters. Therefore, by presenting himself as an outsider and fighter against the old and corrupt politics, Bolsonaro seeks to embody the ideal of fixing and saving the nation, which is a central element in populist rhetoric (

Wajner and Wehner 2023, p. 4;

Zanotti et al. 2023, p. 13).

In this context, beyond the anti-system discourse, Bolsonarist rhetoric also involves the adoption of “coarse language, which seeks to align with popular vulgarity” (

Leite 2024, p. 196). This strategy is partly indebted to Olavo de Carvalho, who encouraged a tactic frequently employed by Bolsonarism, especially on social media: “the attack below the belt”—that is, “one should not combat the opponent with ideas […] but with assaults aimed at discrediting them” (

Oyama 2020, p. 198). This characteristic of Bolsonarism fits

Wodak’s (

2018) concept of shameless normalization—namely, the normalization of taboos and the justification for breaking parliamentary decorum. Within it, the use of content, terms, or expressions that were until then conventionally prohibited or socially unrecommended are permitted and even encouraged in the name of the political agenda.

Another core element is “structural denialism”, through which the ideological expressions of reactionary populism and the political practices of the Bolsonarist movement are manifested (

Lynch and Cassimiro 2022, p. 136). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the narratives promoted by the Bolsonarist movement reproduced “discursive hallmarks of the anti-science populist movement” by attempting to delegitimize scientific and health authorities, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) (

Fernandes 2022, p. 86). Bolsonarist rhetoric is also known for its relentless attacks on the Judiciary and major press outlets, intending to discredit them through methods of mass disinformation, via the dissemination of fake news through digital channels (

Silva 2020;

Checchia et al. 2023;

Marques 2023). More recently, by even advocating for authoritarian and anti-democratic solutions, Bolsonarism has embraced discourses with a conspiracist tone (

Rennó 2022, p. 149).

Therefore, structural denialism seeks to destroy the rational pursuit of truth as a foundation of collective life and the social fabric, making dialogue between different parties undesirable—and impossible—thereby treating political disagreement as “open warfare” (

Lynch and Cassimiro 2022, p. 138). This perspective, which requires the suspension of democratic normality, transforms rational political debate into a gladiatorial arena. It is precisely this logic that constitutes another essential formative element of Bolsonarist discourse: argumentation based on the idea of an internal enemy to be combated, or a “scapegoat”, which configures the so-called rhetoric of hate and resentment (

Akgemci 2022;

Rocha 2023). The enemy to be defeated can be a physical person, like Lula; a social organization, such as the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST); an institution, like Rede Globo, which is the largest media group in Brazil; or even an ideology, such as communism (

Paludo and Fraga 2020). Anchored in morality and theocracy, Bolsonarist discourse presents strong religious and Manichean overtones, ultimately dividing the world between good and evil—“Brazil is dominated by evil, according to this standpoint, and must be saved” (

de Castro 2019, p. 73).

Given that every antagonist presupposes a hero to fight against and an innocent to be saved, the Bolsonarist narrative frequently resorts to messianic appeals, grounded in the premise that the country, immersed in a state of socioeconomic chaos and moral degradation, needs a grand national project of salvation—often associated with the personal figure of Jair Bolsonaro or with the political movement of conservatism as a whole (

de Brito and Lara 2023). This messiah is tasked with protecting the “cidadão de bem” (upstanding citizen), a recurring term in Bolsonarist rhetoric that represents the voter who embodies “us”, while non-Bolsonarists represent “them”. It is around the figure of the “upstanding citizen” that elements such as militarism, anti-intellectualism, anti-communism, anti-corruption discourse, and social conservatism, among others, converged (

Nunes 2022). The “upstanding citizen” is the Bolsonarist rhetorical avatar employed in the rhetorical war against the “elite of leftists personified in the Workers’ Party, the political establishment, the traditional media and the intellectual/cultural elites” (

Luz 2023, p. 187). Thus, it is evident that Bolsonarist rhetoric resembles conspiratorial rhetoric in various degrees and forms, as both present in their discursive ensemble the elements of a conspiring group, a conspiratorial plan, and an effort to maintain secrecy, which will be further explored in the next section.

3.3. Synthesis of the Dimensions: Bolsonarism as a Conspiracist Worldview

Considering that Bolsonarism is a sociopolitical phenomenon with a Manichean and sectarian-religious bias, which establishes the concept of a culture war as its paradigm and articulates feelings like fear and resentment as political-electoral fuel, it is more than plausible to assert that it constitutes a form of interpreting reality. This worldview is grounded in reactionary authoritarianism and populism, conservatism, and Judeo-Christian prejudices.

Relying on counter-epistemic knowledge and disinformation mechanisms to disseminate its ideology and fight against the system—whether the media, science, academia, or political institutions—the Bolsonarist worldview operates through structural denialism and an “us versus them” logic, employing conspiracy narratives as inherent resources for its logic and modus operandi.

Just as conspiracy theories are a way of explaining the complexity of contemporary life, Bolsonarism is a conspiracist worldview that interprets political and economic crises as the direct and unequivocal result of society’s moral and religious degradation and the communist threat, whose main outcome is the corrosion of trust in democratic institutions.

The next section will identify conspiratorial epistemological and narrative elements in the speeches of Bolsonarist members of Congress during their official duties, thereby strengthening the arguments and corollaries posed thus far with empirical data.

4. Sources and Methods

This article examines floor speeches delivered in Brazil’s Chamber of Representatives between 2019 and 2024 by politicians affiliated with the Liberal Party (Partido Liberal—PL). Our most important objective is to identify their use of epistemological and narrative elements typical of conspiracy theories.

Our corpus includes 9994 floor speeches from all 63 federal representatives elected by the PL in 2022 for the current 57th Legislature (1 February 2023—31 January 2027) who also served in the previous legislature (1 February 2019—31 January 2023). Given that our study’s timeframe spans two legislative terms (from 2019 to 2024), only PL representatives who were re-elected in 2022 were considered. Speeches by new representatives elected under the party banner in 2022 were excluded from the corpus to avoid distortions in the quantitative analysis of the year-to-year evolution of conspiracist speeches.

The Liberal Party is a political organization, founded in 1985, that advocates for the ideals of liberal economic doctrine and is considered part of the Right wing of Brazilian politics. In 2006, the PL merged with the Party for the Reconstruction of the National Order (PRONA), changing its name to Republican Party (PR). In 2019, it resumed its original name, Liberal Party. Two years later, in 2021, it welcomed the affiliation of then-President Jair Bolsonaro, who became the central political figure of the party (

Damico 2024).

Following Bolsonaro’s affiliation, the PL tripled its caucus in the Chamber of Representatives, rising from 33 in 2018 to 99 elected representatives in the 2022 election (

BBC News Brazil 2022). This justifies the choice of the Liberal Party as our research subject, since it currently functions as the main political platform for Bolsonarism in Brazil.

The technique employed for data collection and the subsequent evaluation of the corpus consisted of documentary analysis (

Cellard 2008;

Grant 2018) with elements of content analysis (

Riffe et al. 2005;

Bardin 2011). This approach allowed for the systematization of a set of data in order to understand its meanings by identifying patterns and trends. Thus, our study was based on the analysis of the shorthand records of parliamentary speeches made available on the Chamber of Representatives website (

https://www.camara.leg.br/deputados/quem-sao; accessed on 10 June 2025).

A search system for the shorthand notes was used to identify occurrences of the following main keywords and key phrases, among others: “Supremo Tribunal Federal” (Supreme Federal Court); “Ditadura do Judiciário” (Judicial Dictatorship); “fraude nas eleições” (election fraud); “censura” (censorship); “perseguição contra conservadores” (persecution of conservatives); “comunismo” (communism); “grande mídia” (main-stream media); “valores cristãos” (Christian values); “cloroquina” (chloroquine); “vacina do coronavírus” (coronavirus vaccine); “tratamento precoce” (early treatment); along with variant or related expressions. These terms were selected because they reflect a significant portion of the debates within the current Brazilian sociopolitical context.

An instrument was created in this research for analyzing parliamentary speeches, with the objective of identifying elements of conspiracy theory from both epistemological and narrative dimensions, as shown in

Figure 1:

On 14 March 2019, the Supreme Federal Court (STF) initiated Inquiry No. 4781/DF, known as the “Fake News Inquiry”, with the objective of investigating fraudulent news, threats, and other offenses against the honor and security of the Court. In the following years, several other investigative procedures were initiated, such as the inquiries into digital militias

2 and anti-democratic acts (

Federal Supreme Court (Brazil) 2025)

3.

These successive investigative procedures have fostered—and continue to foster—under Bolsonaro’s leadership, reactionary political movements from a segment of society, which began to vehemently criticize the top judicial bodies regarding their alleged judicial activism and their supposed role as agents of a militant democracy (

Martins and Sampaio 2024).

In extreme cases, the most radical wing of the Brazilian Right, motivated by disbelief in democratic institutions and distrust in the 2022 electoral result, has gone so far as to openly advocate for unconventional political solutions, such as military intervention, the removal of elected authorities, and the closure of judicial institutions (

Rennó 2022).

In addition, in 2020, following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, a growing anti-vax movement emerged in the country. This movement was frequently associated with hostility toward official recommendations issued by health authorities and the promotion of alternative drug therapies without scientific backing (referred to as “early treatment”). These factors have contributed to reducing the effectiveness of public vaccination policies (

Sobreira et al. 2024).

With our corpus so defined, we investigated the presence, within the studied parliamentary speeches, of conspiracy narratives and their epistemological and narrative elements, which are part of the tradition of conspiratorial explanation discussed in the previous section. Consequently, it was possible to group narrative conspiratorial elements into three categories: (1) the conspiring group; (2) the conspiratorial plan; and (3) the effort to maintain secrecy. Furthermore, the following epistemological emphases were also identified: (1) Manichean, (2) speculative, (3) science-mimetic, (4) unconventional, (5) populist, and (6) self-sealing.

This investigation of the parliamentary speeches was guided by an inductive perspective, moving from the parts to the whole. In this way, the identification of specific conspiratorial elements, whether of an epistemological or narrative nature, led to the construction of a broader framework. Much like assembling a puzzle, the evaluation of individual elements allowed for the organic integration of a conspiratorial logic and a conspiracist rhetoric, culminating in the visualization of a broader conspiracy theory that permeates the parliamentary speeches thus analyzed, which we call “The Grand Collusion” (O Grande Conluio), and which will be properly explored in the next section.

5. Findings: Conspiracy Theories in Parliamentary Discourse

Of the 9994 parliamentary speeches examined in this study, 387 of them (4%) contained conspiratorial elements of a narrative and/or epistemological dimension. These were delivered by 25 out of the total of 63 federal representatives whose speeches were included in our corpus.

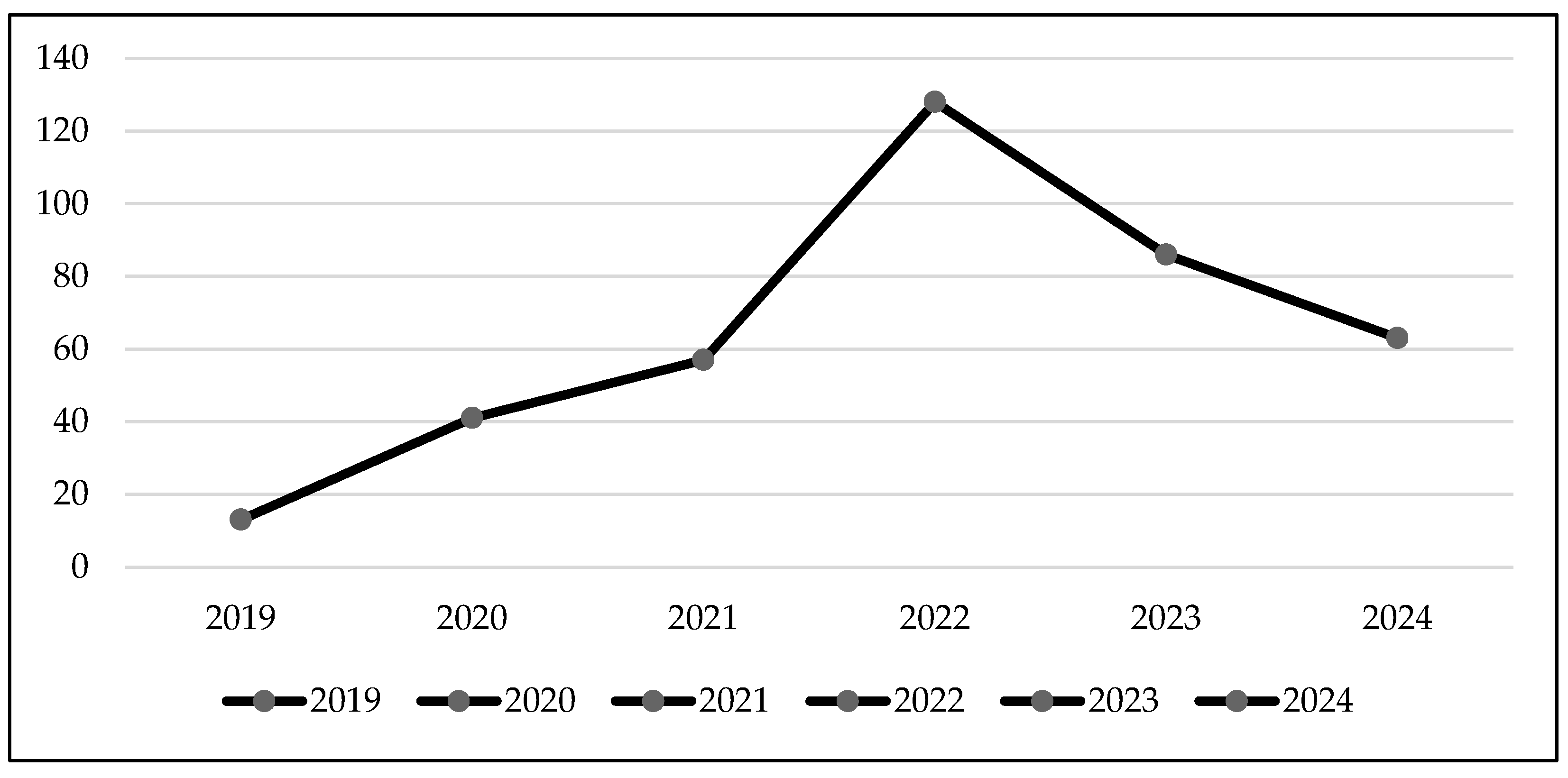

Figure 2 shows that between 2019 and 2021, while the representatives were still part of Bolsonaro’s governing coalition, the quantity of conspiracist speeches was lower. This number grew as the election year of 2022 approached. In 2022, there was an explosion of speeches that had a conspiracist tone, precisely in the year when general elections were held.

This study’s data indicate that the Bolsonarist federal representatives under study may have used conspiracy narratives as a strategic electoral tool, aimed at pleasing their core constituency or influencing voters’ opinions toward a particular sociopolitical worldview during the election process.

After the 2022 elections, in the years 2023 and 2024, corresponding to the first half of the new Lula government, the quantity of conspiracist speeches decreased but remained at levels higher than the years prior to the election, when Bolsonaro was still president. These numbers suggest that when a conservative representative is a member of the opposition they have greater political incentives to use a conspiracist rhetoric compared to the period when they support the governing coalition. Thus, the analysis of the parliamentary speeches was divided into two parts, following the didactic systematization proposed in the sections that discuss this study’s key concepts. Unlike the sections on the concepts of “conspiracy theory” and “Bolsonarism”, the decision was made to begin the analysis with the narrative elements, followed by the presentation of the epistemological elements.

There is a reason for this change in our approach. The collection and analysis of the data, as we mentioned previously in the methodological section, was guided by an inductive theoretical-methodological perspective, which allowed for the identification of the elements and their subsequent categorization to generate a broad portrait of the “Grand Collusion” conspiracy theory. However, to make this paper’s explanation of our analysis of the results more didactic and clear we have chosen to present such data from a deductive perspective, in which the reporting of the results begins with the narrative elements, since this is how they allow for a clearer visualization of the general framework of the Grand Collusion.

5.1. Conspiratorial Elements of a Narrative Dimension

The conspiracy narrative contains three basic elements: the conspiring group, the conspiratorial plan, and the effort to maintain the conspiracy’s secrecy. The present study identified all these narrative elements as belonging to the conspiracist rhetoric that the parliamentary speeches articulated, as shown in

Table 1:

As seen in

Table 1, within the category of the “conspiring group”, the most prevalent element in the conspiracy narratives is the anti-judiciary discourse: 203 occurrences. This represents the highest incidence rate (52%) among the total corpus of 387 conspiracist speeches. The “conspiratorial plan” as a narrative category (the only one not subdivided into discursive elements) appears 27 times. Its lower frequency can be explained by its high narrative complexity, as it constitutes the central element of the conspiracist rhetoric, around which all other narrative aspects orbit. Indeed, the conspiratorial plan, much like a puzzle, could be best identified by examining the set of narrative elements sparsely contained across all speeches, rather than by analyzing each speech in isolation. Finally, for the “effort to maintain secrecy” category, the discourse on the alleged prevalence of censorship against the conservative movement was the most frequent: 52 occurrences. The next section will explore the nuances of each of these three elements in the speeches of the PL federal representatives in greater depth.

5.1.1. The Conspiring Group

The analysis of the parliamentary speeches of our corpus revealed a pattern typical of conspiracist rhetoric: the designation of a conspiring enemy as villainous, selfish, and malevolent. The enemy is not necessarily an individual but can be a system, institution, or ideology. Depending on who this villainous conspirator is, the speeches were categorized into four types: (1) anti-judiciary; (2) anti-communism or anti-left; (3) anti-mainstream media; and (4) anti-international organizations. The anti-judiciary discourse focuses its attacks on three actors: the STF (Supreme Federal Court), the TSE (Superior Electoral Court), and Minister Alexandre de Moraes. These agents are accused of systematically acting arbitrarily and in an authoritarian manner to weaken the democratic regime:

“[…] something is happening with the Supreme Federal Court: it has become totalitarian, punishing representatives and also citizens who criticize the STF, as if this had any legal basis, justifying censorship, justifying illegal inquiries, illegal and unconstitutional arrests, even undermining the Constitution, trampling on Article 53, which guarantees parliamentary immunity for representatives and Senators who represent the people, and also on §2, the formal immunity, which states that representatives and Senators, after being sworn in, cannot be arrested, except in flagrante delicto for an unbailable crime. This totalitarianism has advanced to a point that no one can take it anymore. Anyone who agrees with and condones this type of action is no more than scum. What we are witnessing is a genuine attack on our institutions and our democracy”.

The STF and TSE are imputed with the malevolent mission of persecuting the conservative movement or Bolsonarist citizens: “[…] persecution by the Supreme Court and the TSE affects a broad political spectrum. They see us conservatives as adversaries. They want to put an end to the Right wing, to what they call Bolsonarism, and they think that it is perfectly acceptable” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). Minister Alexandre de Moraes, the only villain who is singled out in this subcategory, is portrayed as having a dictatorial posture and as if acting against the legitimate interests of the people, suffocating the other branches of the Republic: “A single Minister has put a leash on the Presidency of this Country. The Executive Branch has bowed to a single Minister. We are living in a time when a single Minister has managed to shackle the entire Country and attack Brazilian democracy” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

The second type of enemy is the political-party sector of the Left, or Communism, both generally used as synonyms. The Leftist movement is portrayed as a direct and imminent threat to family and religious values: “everything the Left touches, rots. It rots the Country, it rots the family. And now they are even trying to touch religion; they want to rot religion too” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The allusion to this type of enemy is characterized by a rhetoric that fosters fear and by a discourse that aims at Christianizing society, focusing on the narrative of the imminent danger of communism being implemented in Brazil:

“Our flag will not be red! Our Country will not be communist! We will not accept this kind of thing. They will not put lying words on our lips. The Church is a place of peace […] Wake up, Christians of Brazil! We are under attack and we are being persecuted”.

A characteristic omnipresence is attributed to the Machiavellian communist project, which would allegedly operate across various institutional levels of civil society and public power: “We have seen a pernicious ideology get installed in our cultural, educational, and media spheres, totally dominating the means of communication, universities, and even schools” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). It is common to associate the rise of the Left with the risk of the extinction of democracy and the loss of fundamental individual freedom and guarantees:

“We know that the Left must control the narrative because they truly want to turn Brazil, in their totalitarian frenzy, into a communist country by controlling the free flow of information and the narrative. Therefore, we cannot accept this strategy of the Left to try to restrict, to disrespect, and to shut down the National Congress”.

A third type of villain is the press, that is, conventional media outlets. The mainstream media is portrayed as corrupt, biased and controlled by the Leftist movement: “I conclude my remarks by alerting our people to the unspeakable maneuvers of a corrupt press that has sold itself to the São Paulo Forum and is paying its dues, even if it has to use lies and distort facts in order to create fabricated news” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The credibility of the press is habitually called into question, and accusations are made that it fabricates news or creates fake news with the specific purpose of damaging Bolsonaro’s image:

“So, this is fake news from the press, trying to pin on the greatest President in the history of this Republic, Jair Bolsonaro, a coup that never existed. The press needs to start telling the truth again to recover its credibility, because it now has no credibility, since it is inventing something that never existed. The Brazilian press is the queen of fake news”.

Rede Globo is the entity that the speeches target most frequently, being held responsible for the destruction of conservative values: “the Brazilian people are tired of the demoralization propagated by Rede Globo and its lackeys—a network that disrespects families, that corrupts the innocence of our children through content that is, in reality, moral garbage” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

The fourth type of antagonists, cited much less frequently, comprises foreign bodies such as the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Mention of this group confers an international status upon the conspiratorial plot. It is alleged that the UN would act gradually in Brazil to enforce its agenda, which the speeches under study deem as progressive or Leftist: “this is the UN’s policy: one little brick at a time, until finally, one last little brick in the Brazilian legal system completely locks the door of the little house of their ideological project for this Country” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). More tied to the pandemic situation, some of the speeches under study also target the World Health Organization, sometimes accusing the entity of collusion with China:

“We must understand the objectives of another Chinese organism called the World Health Organization. I never get tired of calling it the “World Organization of the Clueless,” because, since the beginning of the pandemic, they have been wrong more than 50 times. They have deceived the world’s people more than 50 times”.

Regardless of the antagonist—be it the judicial system, communism and the left, the press and media, or international organizations—the rhetoric is one of vilification and demonization. There is no room in the parliamentary discourse for ideological disagreements or political differences, as it is a case of light versus darkness. They convey the idea that the democratic process is in fact an arena where good and evil are locked in combat.

5.1.2. The Conspiratorial Plan

As for the “conspiratorial plan” as a narrative element, it was possible to ascertain that the speeches were organized around a grand plot: a collusion between Leftist politicians and the top echelons of the Brazilian Judiciary (STF and TSE) to persecute and censor conservatives and Bolsonarists, with the help of a corrupt mainstream media acting in a biased and activist manner against the Right. The alleged intended outcomes would be: fraud in the electronic voting machines to elect Lula and the establishment of a judicial dictatorship in the country. “Now, in reality, we are not just being held hostage by one branch of power; we are being held hostage by two branches that are in collusion” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The alliance between the Judiciary and Lula’s government is frequently invoked to posit the existence of systematic persecution against conservatives, Christians, or even the Brazilian people in general: “it is a joint persecution by the Government and the Judiciary against those who criticize the Government” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). Our study found that this narrative intensified during the electoral period: “we are in an electoral period and conservatives are being hunted down” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). At times, the persecutory scenario against Christians takes on a global dimension in the speeches: “Christophobia exists, it is already spreading across the world in large strides. Even so, we are here” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

Due to a rhetoric that instills fear, Bolsonaro is frequently acclaimed in the speeches as some kind of savior of the people with messianic attributes: “This is a myth that reinforces Bolsonaro as a leader, a born leader of this country, almost a work of God. He is no average Joe trying to defeat the system. Bolsonaro is one in a million” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The press is considered fundamental in this conspiratorial plot, because it would help the Left to destroy Bolsonaro’s image in favor of Lula’s: “Today we see a good part of the Left—I won’t say all, but the extreme left—and a good part of the media, co-opted by the extreme left and by globalist thoughts and ideas, dehumanizing those who support President Bolsonaro” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The first consequence that the narrative of the grand plot presents is that the 2022 electoral process was allegedly manipulated and its result falsified for Lula’s benefit. This rhetoric of electoral fraud began early, still in the pre-electoral period: “This mob wants to rig the elections so that Bolsonaro is not re-elected. They are wasting their time. Even if there is fraud, Bolsonaro will be re-elected, yes!” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

The allegation of ballot box fraud is usually accompanied by a strong populist discourse: “Almost all the Brazilian people are saying that […] they do not accept having been deceived in the elections” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The speeches also mention so-called proof of fraud in the electoral system and, consequently, call for the annulment of the election: “The PL presents a report that shows serious inconsistencies. In fact, an Argentine showed serious inconsistencies, and the press is turning a deaf ear. […] So, if the first round must be annulled, the second round and everything else should be annulled” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). There is a clear effort to construe a narrative in which the Brazilian Electoral Justice system took sides and acted deliberately and systematically to elect Lula in 2022:

“This electoral campaign showed that the Brazilian Judiciary had a side, and was relentless in helping it defeat its opponent. This became very clear. Minister Alexandre de Moraes, in fact, was the big winner of the election. The Superior Electoral Court took measures, one after another, against the President of the Republic”.

Associated with the rhetoric of an electoral coup is the recurrent allegation that an authoritarian regime exists in Brazil, orchestrated by the Judiciary, called the “Dictatorship of the Robe”: “we are living […] the dictatorship of the robe. The coup has been carried out. We are in a state of exception. The sheriff of the TSE […] has already torn up the Federal Constitution” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The conspiratorial plan is referred to as a “modern coup”, precisely because a complex multi-institutional plot is presented as uniquely singular, without precedent in history:

“In Brazil, there has been a breach in democracy. There has been a modern coup in which a partnership exists among some Ministers of the STF, some political parties and the new form of domination by the media. They are bankrolling the whole thing […] Today we have a Minister who dictates rules for the country”.

In the total number of speeches of our corpus, impactful expressions such as “dictatorship of the robe”, “judicial dictatorship”, “dictatorship of the STF”, “Judiciary’s AI-5”, and equivalent terms were used 171 times. According to the conspiracy narrative, Brazil is currently governed by a peculiar symbiotic relationship of power formed by Lula’s Executive branch and Alexandre de Moraes’ Judiciary branch. On certain occasions, it is asserted that this amalgamation of powers is led by Lula’s government: “The Supreme Federal Court acts in a symbiotic manner with the Government, obeying the measures that the Government imposes and its political whims” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025), with the Judiciary being a mere instrument used at the pleasure of the Leftist parties:

“[…] in recent years, the Supreme Federal Court has been the Left’s playground, it has been a mechanism for Leftist activism. […] We assessed, during the electoral period, the conduct of Minister Alexandre de Moraes: even while being President of the TSE, he was Lula’s chief campaign promoter during the election”.

In other instances, a different hierarchical relationship is indicated, with the symbiotic power structure being spearheaded by the STF, in the person of Minister Alexandre de Moraes:

“For some time now we have been under the aegis of a dictatorship that settled in gradually. It is a modern dictatorship. How was it established? Without firing a single shot, through a media apparatus, through the control of institutions, and through the power of some Ministers of the superior courts. The general commander of this dictatorship, the helmsman, has been Minister Alexandre de Moraes”.

5.1.3. The Effort to Maintain Secrecy

As for the effort to maintain secrecy, the speeches were subcategorized into three subject types: (1) unverifiable ballot boxes; (2) alleged censorship applied by the STF to silence conservatives; and (3) the alleged fabrication of the January 8, 2023, attacks by Lula using Leftist “infiltrators”.

The statement that the electronic ballot boxes were not verifiable appeared many times in the 2021 Bolsonarist campaign. This fact resulted in the proposal for a Printed Vote Constitutional Amendment (PEC do Voto Impresso, Proposed Amendment to the Constitution No. 135/2019), which, however, was rejected by the Chamber of Representatives that same year (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2021). There was a higher concentration of speeches about unverifiable ballot boxes in the year preceding the 2022 elections. The argument is relevant because it pointed to a basic secrecy strategy by the alleged conspiratorial group, which, in this way, could secretly manipulate and control the outcome of the election: “[…] our ballot boxes are unverifiable, our ballot boxes are inaccessible to those who are not part of the TSE’s top echelon. The TSE’s technicians are those who count the votes today, and they do that secretly” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

The efforts to maintain secrecy go beyond the elections. They are part of a narrative according to which there is a current state of systematic censorship imposed by the STF against conservatives and Right-wing politicians, with the objective of silencing those who fight for democracy and seek to denounce the alleged “judicial dictatorship”: “[…] not just one, but other Ministers have endorsed the application of censorship in Brazil. We are living in a period of censorship, decreed by the Supreme Federal Court” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The argument that the STF imposes censorship is central to these speeches because it reinforces the secretive, conniving, and cunning nature of the conspiratorial plan:

“[…] not to mention the field of democracy, where, in collusion with the STF, the PT and its tentacles in the press and academia supported the return of censorship and of political prisoners, as well as legal aberrations, such as the disrespect for parliamentary immunity and for the principle of individual criminal liability”.

This type of discourse is often associated, with populist undertones, with repeated calls for the impeachment of STF ministers, as the alleged condition of censorship itself is presented as the grounds for the removal request: “No matter how much the Left unites with high authorities who persecute and censor us, we will not be silenced. Out, Minister Alexandre de Moraes! Hurray for impeachment! […]” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

Regarding the attacks of 8 January 2023, on the buildings housing the Three Branches of government in Brasília, the speeches in our corpus attempt to invert the logic of the event, narrating that those actions were the product of Machiavellian planning by the Left, through the actions of its agents previously infiltrated in the popular demonstration: “On the 8th, there was a major riot, full of infiltrators. […] the vast majority who invaded and vandalized buildings were, in fact, infiltrators from the Left, infiltrators who put on a Bolsonaro shirt to break things” (Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

Besides the “infiltrators”, there are speeches that directly blame President Lula for the event, either through a “[…] total willful omission by the Federal Government to allow the acts of January 8th to happen” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025), or because “He [Lula] set it up with the Minister of Justice. They wanted it to happen. This is the great truth about January 8th: it was brought about by a plot, a setup” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

In light of the above, the examination of parliamentary speeches delivered between 2019 and 2024 reveals the existence of sufficient rhetorical elements to confirm the supposition that a conspiracy narrative was adopted in the floor speeches of federal representatives. This narrative corresponds to the alleged existence of a grand collusion between the top echelons of the Judiciary, spearheaded by STF Minister Alexandre de Moraes, and the Brazilian Left, led by Lula, with the direct assistance of major mainstream press outlets (e.g., Rede Globo), and the indirect help of multilateral organizations (UN and WHO).

The main objectives of this alleged collusion are to rig the 2022 elections and to systematically persecute and censor Right-wing politicians and conservative citizens. The conceptual characteristics and epistemological traits that validate the identification of “The Grand Collusion” as a conspiracy theory are presented next.

5.2. Conspiratorial Elements of an Epistemological Dimension

Our analysis identified the presence of the following six emphases pertaining to the epistemological dimension in the parliamentary speeches of our corpus: Manichean, speculative, unconventional, science-mimetic, populist, and self-sealing. The same speech can contain one or more of these epistemological elements, as detailed in

Table 2:

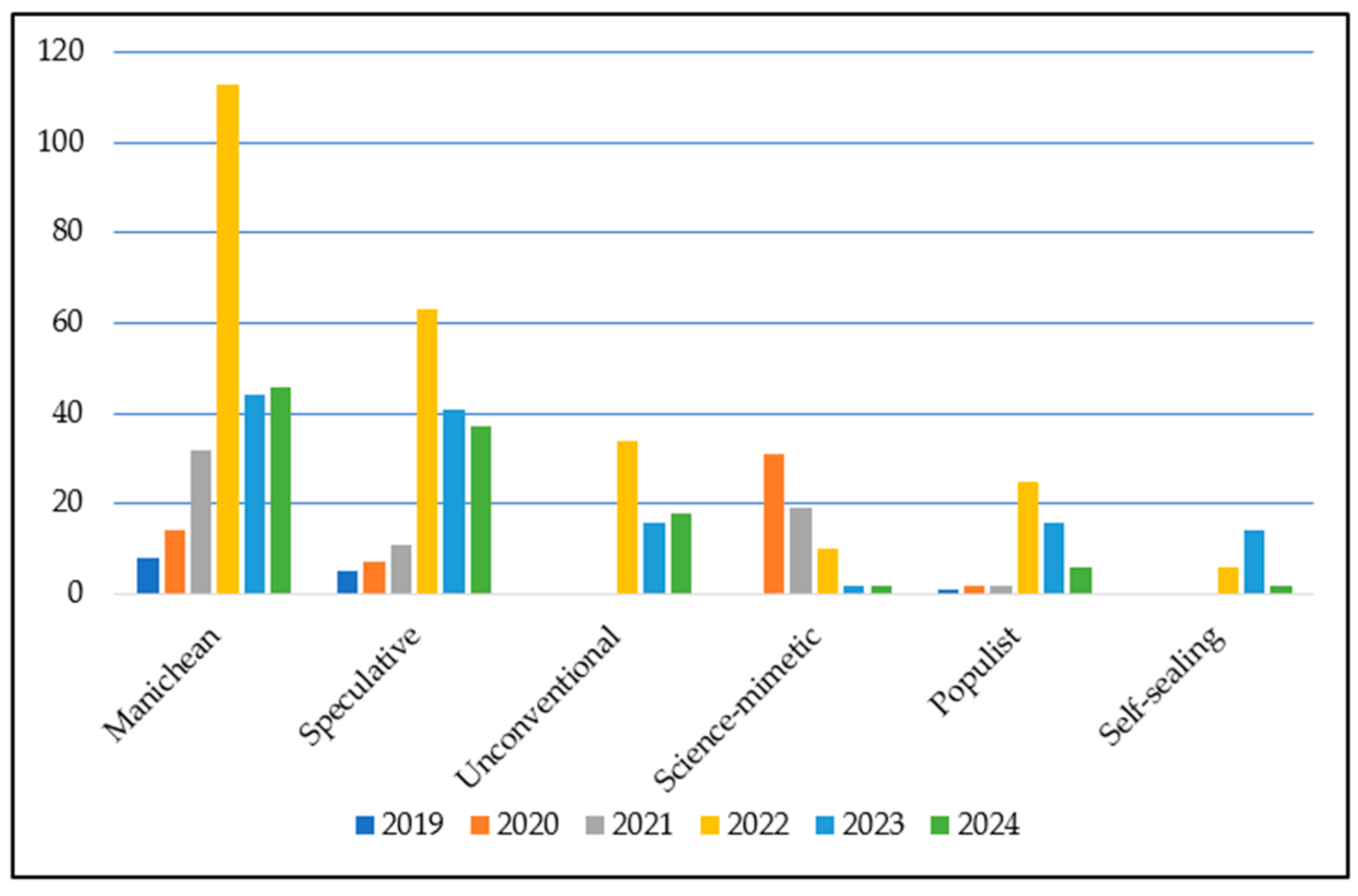

Figure 3 reveals that the Manichean emphasis is the one most frequently identified by the content analysis of the speeches, followed, in descending order, by the speculative, unconventional, science-mimetic, populist, and self-sealing emphases.

5.2.1. Manichean Emphasis

A Manichean emphasis is the epistemological element found most frequently in our corpus. It is present in 66% of the speeches that resort to a conspiracy theory rhetoric. The Manichean approach aims to explain reality through a dualistic view in which there is a tension between good and evil. In this sense, the discursive lines revolve around combative appeals, intended to unite conspiracists in defense of cherished values against common enemies, who are the conspirators.

The Manichean rhetoric has as its target an entire political group whose agenda is progressive, accusing it of aiming to destroy the family and good customs: “the Left, based on Lenin’s Decalogue, wants the end of society, the end of the family, the end of religion; it wants the whole world to be divided; and it wants society in tatters” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). As the country’s great leader of the Left, President Lula is considered one of the main antagonists to be confronted: “the dictator who is in the Planalto [Presidential Office] wants to eradicate the family, patriotism, and good customs. Lula and his friends aim to eradicate the family, patriotism, and the culture that formed the Brazilian people” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The enemies can also be a top state body, such as the Supreme Federal Court (STF), one of the most frequently cited institutional adversaries in the speeches:

“There is no inertia on the part of this Parliament regarding these matters that are being brought before the Supreme Federal Court. On the contrary, they are intentional about it! So, it really is a circus spectacle, because it seems they laugh at this Parliament, they laugh at the Brazilian population, and that is why, Mr. President, that the people see them as enemies—and I, personally, also need to see them that way”.

Thus, the Judiciary, through its superior courts, is viewed as the great enemy to be combated, because it would allegedly act in a covert alliance with the Left: “there is an alliance between the left and the Judiciary, in the person of Minister Alexandre de Moraes, who has always decided against the population. Because of this, the population turns to the Armed Forces” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The Judiciary is labeled as the great evil that seeks to eliminate the values of the conservative movement and undermine the democratic system in the country:

“How can a Minister of the TSE and the Supreme Court engage in political opposition against the President and still beat his chest and say: ‘We are the good, we are democracy?’ […] Democracy is indeed under attack, but not from the President of the Republic, who represents no evil. It is under attack when a Minister of the Supreme Court, who must be impartial, engages in partisan politics, confronts, and attacks the President of the Republic”.

Alongside Lula, the person most frequently singled out in the speeches as the great opponent of the Brazilian people is STF Minister Alexandre de Moraes, often labeled with grave, disparaging adjectives: “we cannot continue to allow representatives to be silenced by the pen stroke of a Nazi, fascist, and dictator Minister, like Alexandre de Moraes” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025), who “has a Gestapo alongside him, to persecute all those they want” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). The Minister is often referred to not only as an enemy of the people but also as the great opponent of the rights and prerogatives of the representatives: “it is impossible for the Minister of the Supreme Federal Court Alexandre de Moraes to continue attacking this House, subjugating this House and the members of this House” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

The press is also considered an integral element in the machinery of evil forces. It is accused of acting to destroy the moral values of the Brazilian family: “a large part of the press, in the name of the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression, acts in a deliberately subversive manner, betraying its historical mission to inform, instruct, and entertain the public, which is increasingly saturated with its lies and immoralities” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

5.2.2. Speculative Emphasis

The speculative approach is present in 42% of the speeches in which our study found conspiratorial elements. This type of rhetoric is based on conjectures and suppositions, and not on knowledge and solid evidence. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were a great amount of conjectural claims regarding both the origin of the virus (“China created the virus”), the measures to control its spread (“the mask was useless”), and even the forms of treatment for the disease: “if they had listened to President Bolsonaro and if, at the beginning, when they had minor symptoms, they had already taken chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, we would have had far fewer deaths in Brazil. That is the truth” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

Speculations about the maligned communist project that the Left would seek to implement in Brazil together with other Latin American countries are frequent: “the São Paulo Forum

5 intended to transform Latin America into a great communist nation” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). Inferences are made that the Left is financed by drug traffickers: “We know that drug trafficking financed—and finances—left-wing parties in our country” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

Furthermore, there is the premise that Left-wing governments act in collusion with the press: “previous governments paid billions to the press to praise them, while Brazil was being robbed. In the Bolsonaro Government, the press is not paid to praise” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). Thus, a tribal truth is created that the Brazilian mainstream media is corrupt and financed by the Left: “We live, unfortunately, in a country where a large part of the press is yellow. Yellow press is one that only reports news if it receives money and criticizes when it doesn’t receive money” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

To reinforce the rhetoric of the alleged current state of censorship and persecution of conservatives, several speeches with a megalomaniacal bias suppose that this stems from a major international political project: “It is impressive how they attack democracy, institutions, and stability. And now the censorship project also continues, which is not just Brazil’s, it is a worldwide censorship project, which is proceeding at full steam” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). With some frequency, they speculate and cite examples of notable democracies that would no longer be democratic regimes, such as Canada:

“Let us uphold freedom, so that what is happening in Canada does not occur in Brazil—a country that is ceasing to be free and becoming a dictatorship, a tyrannical dictatorship—by someone who wants to punish people who—in an orderly manner—participated in a rally for freedom of choice”.

Regarding the 2022 presidential elections, besides the alleged ballot box fraud without the presentation of probative evidence, many speeches were also found that emphasize a deliberate assistance from the Judiciary in favor of Lula, to the detriment of Bolsonaro, throughout the electoral process. This is done through generic statements such as: “President Lula was not elected, he was appointed by the TSE” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025), or through more specific accusations regarding the Judiciary’s hypothetical

modus operandi:

“The TSE tries to recruit young people, thinking it might be easier for the Left to deceive this segment of the population and thus obtain votes, and it cancels the voter registrations of older people, over 70, who generally have more experience and tend to be more conservative”.

5.2.3. Unconventional Emphasis

The unconventional emphasis was found in 18% of the conspiracist speeches in our corpus. That emphasis may purposely prefer explanations of certain facts in a way contrary to those considered as obvious or consensual in society, an intention that reinforces the anti-system character of this radical political niche:

“Climate change does not exist, nor does global warming! What exists is an international interest to enslave Brazilian agriculture, to bring electric machinery to Brazil and say that all of this is for environmental preservation. Folks, this is just another hoax, it’s just another lie that the Brazilian Left is telling us in order to destroy our agribusiness and hinder our productive farmers”.

Unconventional rhetoric can serve as an instrument for spreading fear for the purposes of electoral propaganda, by announcing the future occurrence of terrifying events that are highly improbable or inconceivable: “vote for the leader [Bolsonaro] who loves this Homeland, who fears God; for the one who will prevent, in our country, churches from being closed, priests from being persecuted, Christians from being persecuted” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). Unconventional parliamentary speeches often do not yield even in the face of established reality. Instead, they construe implausible or bizarre narratives of events that reinforce the Manichean worldview of their supporters. In this sense, the attacks by Bolsonarist citizens on the buildings housing the Branches of the Republic in Brasília on 8 January 2023, are considered the work of communist “infiltrators”, or of the Left: “what coup was seen on January 8th? […] There was mass behavior, with infiltrators causing all that confusion, that uproar” (Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). In certain cases, unconventional speeches attempt to construe a new narrative thread in an attempt to reverse the interpretation of facts in favor of those who support conspiracy theories:

“What happened in our country on January 8th was something surreal. Of course we saw disgraceful acts, but we also watched many emotional videos of patriotic Brazilians who were there at that moment preventing or trying to prevent infiltrators who were in their midst from provoking chaos”.

The unconventional assertions in our corpus also aim to contradict facts regarding the existence of a Democratic Rule of Law in Brazil:

“For several years, public opinion in Brazil—and now internationally—, considers that there is a dictatorship in Brazil, that in Brazil we no longer have a Democratic Rule of Law. We have a state of exception, arbitrary, in which tyrants act freely—above and in spite of the law”.

5.2.4. Science-Mimetic Emphasis

The science-mimetic emphasis accounts for 17% of the conspiratorial speeches identified in this study. Our analysis shows that cases of rhetoric aimed at imitating scientific language peaked in the year 2020, unlike the other epistemological elements, which peaked in the election year of 2022. This was due to the break-out of the COVID-19 pandemic that year, which brought about a political-ideological clash between the then President of the Republic, Jair Bolsonaro—who advocated for the relaxation of restrictive measures and downplayed the impacts of the pandemic crisis—and the Governors, who, in general, argued for the adoption of national and international health protocols to contain the spread of the virus (

de Novaes 2024, p. 75).

Therefore, the vast majority of parliamentary speeches with a science-mimetic emphasis in our corpus relate to sanitary issues of the new coronavirus pandemic, such as, for example, anti-vaccine speeches: “we will have a vaccine that, once made mandatory, can cause serious harm to one’s health, because it was rushed, and it was not made with the objective of treating anyone” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025).

A marked presence of a rhetoric that defended the use of drugs with unproven efficacy in treating COVID-19 was found. In fact, a certain representative, who is not a doctor, even issued a kind of medical prescription from the podium: “The ideal is to use ivermectin from the first to the third day of symptoms. Its efficacy in treatment reaches up to 90%”. (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). In this context, experts from the scientific and academic community are accused of being part of the conspiracy:

“There is no misgovernment, no arbitrariness that has not taken root in Brazil since the arrival of the Chinese virus. True science has given way to scientism, which is merely a slogan intended to silence, even through irresponsible studies that cost lives while the optional use of a cheap, safe, and well-known drug for decades has saved lives: hydroxychloroquine”.

There are narratives that associate drugs of unproven efficacy with federal government public bodies, to give an official appearance to claims cloaked in scientific language: “the Ministry of Science and Technology has already researched and already found a drug that cures 98% of the virus within the first 8 days” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). A widely used line in the speeches is that of the so-called “early treatment of COVID-19”, which became a kind of mantra of the Brazilian far-right during the pandemic. This practice consists of using certain common medications (e.g., dewormers) preemptively, which would supposedly prevent a person from contracting the disease: “Ivermectin is the vaccine against the coronavirus. You can be sure of that!” (

Chamber of Deputies (Brazil) 2025). In certain cases, Bolsonaro’s image is used to lend legitimacy to the discourse:

“He [Bolsonaro] also said that hydroxychloroquine cures, and today, the Governor of São Paulo has coronavirus and is taking chloroquine. So, you see that drugs like ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, zinc, and vitamin D are effective. You just have to use them early”.

Speeches using science-mimetic language related to the reliability of the electronic voting machines were also identified, albeit in smaller numbers. They employ pseudo-technical expressions such as, for example, “breaches in the source code”.