2.1. Theoretical Framework

Much empirical work tends to support the human capital theory which was developed by Becker and Mincer about human capital investment and labour market earnings [

12].

It explains both individuals’ decisions to invest in human capital (education and training) and the pattern of individuals’ lifetime earnings. Investments in education and training entail costs both in the form of direct expenses (like tuition) and foregone earnings during the investment period. Therefore, only those individuals who expect to be compensated by sufficiently higher lifetime earnings choose to invest. The human capital theory also explains the pattern of individuals’ lifetime earnings. In general, the pattern of individuals’ earnings is such that they start out low (when the individual is young) and increase with age, although earnings tend to fall somewhat as individuals near retirement. This pattern occurs because investment in skills acquisition improves earning stream over the lifetime. Going through a process repeatedly makes one a master of the process. Thus, rather than wait endlessly for formal jobs amidst high unemployment rates, young people do take up apprenticeships or informal jobs with a view to becoming a skilled craftsman in the trade selected.

where

PLE represents the pattern of individuals’ lifetime earnings,

IHC represents the investment in human capital, and

FCA represents future career aspiration.

Equation (1) suggests that the future career aspiration of an individual depends on the pattern of the individual’s lifetime earnings and investment in the individual’s human capital.

In similitude with the human capital theory but more elaborate, the “self-concept theory (SCT)” by Donald Super argues that the future career aspiration of individuals changes over time with the acquisition of more experience, the pattern of an individual’s lifetime earnings, gender, education, parental expectations, and parent’s occupation and education level [

18].

where

FCA represents future career aspiration,

PLE represents the pattern of individual’s lifetime earnings,

EXP represents experience,

GD represents gender,

EDU represents education,

PEX represents parental expectation, and

POE represents parent’s occupation and education level. SCT formed the theoretical foundation on which this study was built.

2.2. Survey of Empirical Literature

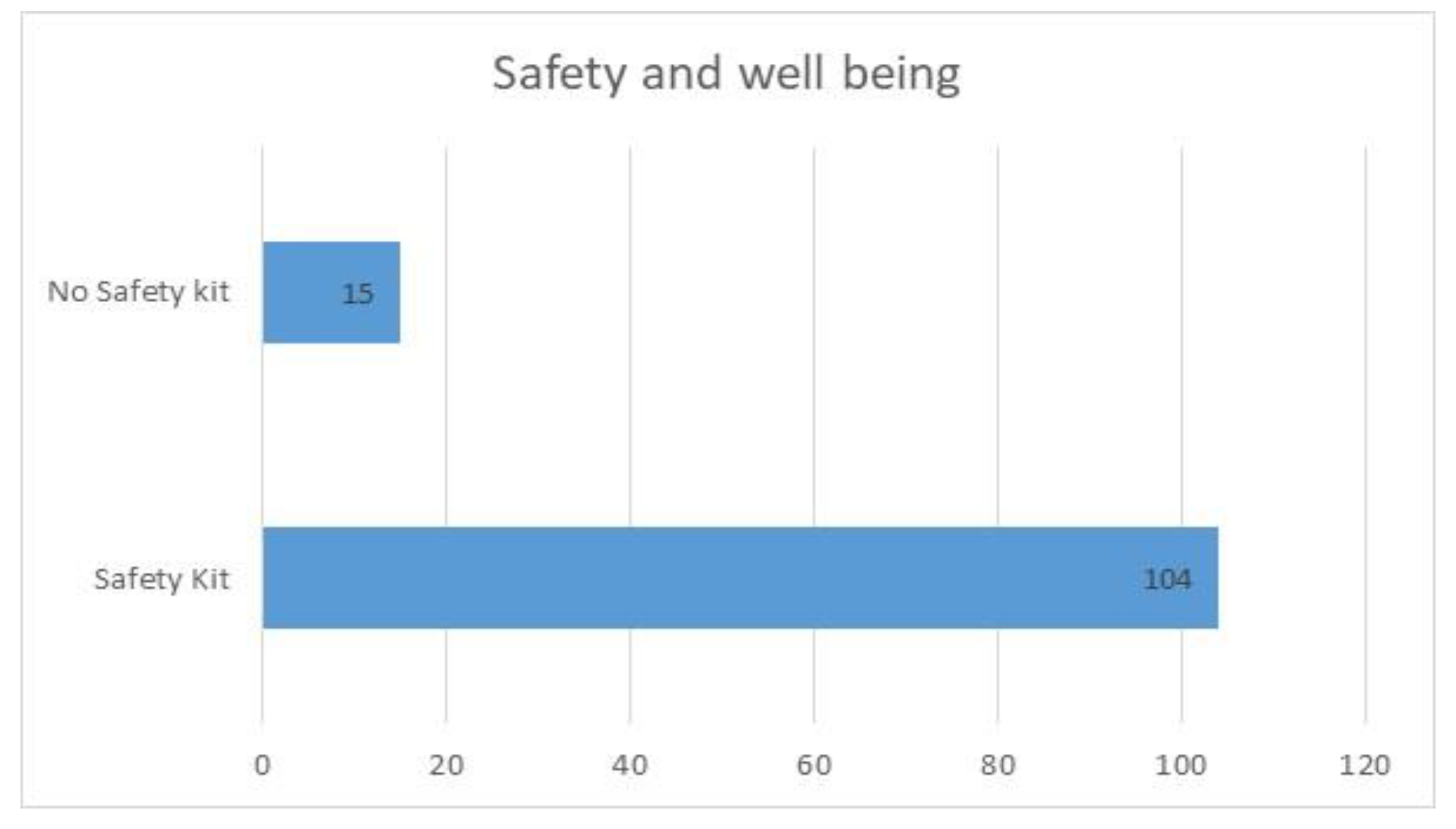

The activities of waste pickers are relevant to the growth of the economy as they help improve environmental quality and promote the health and wellbeing of people [

5,

6,

9]. However, the health conditions of waste pickers are largely at risk because of the unsafe and extremely hazardous means by which they carry out their activities as they work under conditions of physical exertion for extended periods of time and hardly take time out to rest [

11]. It is well documented that solid waste poses a serious risk to human health and the environment [

19]. Economic inadequacies also push waste pickers to consume recovered food waste which can put them at risk of stomach infections, parasites infection, and food poisoning, which can cause nausea and diarrhoea [

20]. The bioaerosols and other toxic compounds inhaled in the combustion process also portend danger to them. Burning waste and fuel exhaust fumes can cause eye irritation, lung infections, decreased lung functions, and different respiratory ailments [

7,

21].

The study by Nguyen et al. [

22], in which 267 waste pickers were interviewed, reported spinal and lower extremity pain related to frequent kneeling which occurred in the process of collecting and sorting of solid waste, which posed as risks to their health and possible future career development. Findings from Mothiba [

23] revealed that only 22% of the interviewed waste pickers viewed their health as poor and, when asked about their future career aspiration, 38% of the interviewed waste pickers intended to further their education, whereas the remaining 62% did not desire further education. The former intended to study nursing, handwork, teaching, and a majority wanted to obtain a Grade 12 certificate which could be obtained after successful completion of high school. The reasons given by those who were not interested in further education were many and varied. Some felt they were too old, others wanted to support their families, and the remainder thought some members of the community would make fun of them if they went back to school and sat in the same class with their children’s age mates. Many of the responding waste pickers indicated that financial constraint was responsible for their early decision to drop out of school to make ends meet. A number of males, as well as females, reported that their peers laughed at them for being in the industry and that they were marginalized, whereas younger waste pickers said they feared public ridicule, and they were afraid to tell some of their friends about the kind of work they were involved in.

Ref. [

12] studied the barriers that prevent street waste pickers from improving their socio-economic conditions. The survey research approach was used in their study, which took place between April 2011 and June 2012. The researchers conducted structured interviews with 914 persons involved in waste picking and a total of 69 off-takers in thirteen major cities spread across nine provinces in South Africa. The results of the study revealed that poor language proficiency, low levels of schooling, limited language skills, low and uncertain level of income, as well as poor access to basic and social needs, hindered waste pickers from improving on their socio-economic conditions. The study recommended the implementation of intervention policies aimed at improving the socio-economic wellbeing of waste pickers.

Ref. [

24] assessed the perception of households on solid waste recycling and the benefits accruing to households in Kaduna state, Nigeria. The approach used in the study was quantitative. Respondents were selected using stratified random sampling, and 500 questionnaires were administered to the households. The study used descriptive statistics to analyze the benefit of and perception of waste recycling. The result of the study showed that households with low income recycled their waste more and earned income benefits as compared with those with higher income. The study also showed that higher-income household’s perception of waste pickers was degrading.

Ref. [

6] studied the social, economic, health, and environmental implications of solid waste scavenging activity in Olusosun, one of the government’s designated open waste dumpsites in Lagos, Nigeria. The study utilized primary data obtained from waste pickers and simple techniques such as mean, frequency distributions, percentages, and cross-tabulations among various variables were used in the analysis and interpretation of the data collected. The results showed that scavengers reduce the waste on the site to almost only organic materials since other materials such as metals, plastic, glass and polythene materials are recovered for reuse or sale. This reduces the quantity and leaves only organic materials to be buried. In addition, scavengers have helped agencies responsible for waste management in reducing financial and technological commitments. The study concluded that scavenging should be regulated to make sure that operations become environment friendly, thus, creating fewer hazards to both the operators and members of the public.

Ref. [

25] studied the role of the informal sector in sustainable municipal solid waste management using Lagos State, Nigeria, as a case study. The researchers examined how informal sector players contribute to waste management, waste recycling, and waste-to-wealth activities in Lagos State, Nigeria. The study was based on the data collected from field observations, interviews, and questionnaires administered to waste collectors, scavengers, waste cart pushers, resource merchants, recyclers, and other stockholders of the informal municipal solid waste management in sixteen local government areas (LGAs) of Lagos State, Nigeria. The results of the study showed that the search for valuables, recyclables, and reusable items at dumpsites has always been driven by poverty and a desire to earn a living. The study concluded that the actors of the informal sector in municipal waste management had been working under conditions that put their health, which was an important asset to them, at risk for not undertaking safety preventions. The study established that there was a ready and profitable market for reusable and recyclable municipal waste materials in Lagos State, Nigeria.

Some studies have proposed that protective gear such as clothing, gloves, and boots should be given to waste pickers to reduce pathogenic infections and increase their activities [

8,

16,

26], however, a lot of controversy has been stirred. It was experienced in Calcutta, India that the waste pickers sold the personal protective equipment (PPE) given to them and preferred to work unguardedly [

27]. Thus, due to the informal and undefined nature of waste picking, their working conditions are somewhat difficult to improve on. Some studies are of the opinion that employment opportunities and decent earnings abound in waste picking activities [

6,

9,

13]; others have questioned the decency of waste picking [

12]. This study was carried out to provide more insight and reduce this controversy by investigating the socio-economic conditions and career aspirations of waste pickers in Lagos State, Nigeria.