Evaluation of Factors Affecting Cucumber Blossom-End Enlargement Occurrence During Commercial Distribution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants, Packaging Material, and Experimental Design

2.2. Preliminary Evaluation of Packaging Films (2018)

2.3. Demonstration Experiment on Real Onsite Transportation (2019)

2.4. Evaluation of the Impact of Packaging Methods and Workers on BEE Occurrence (2020)

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

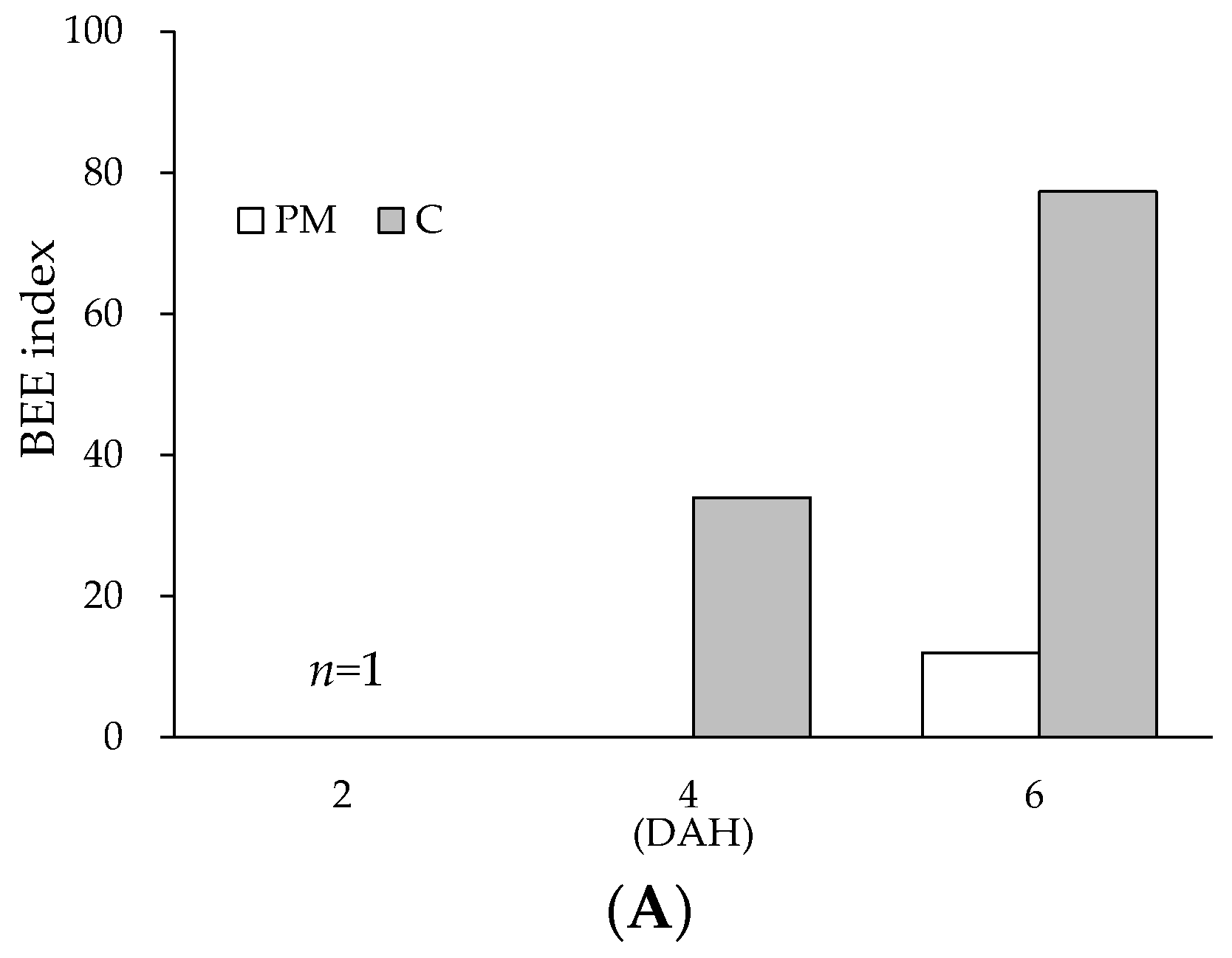

3.1. BEE Suppression Effect of the Different Packaging Films

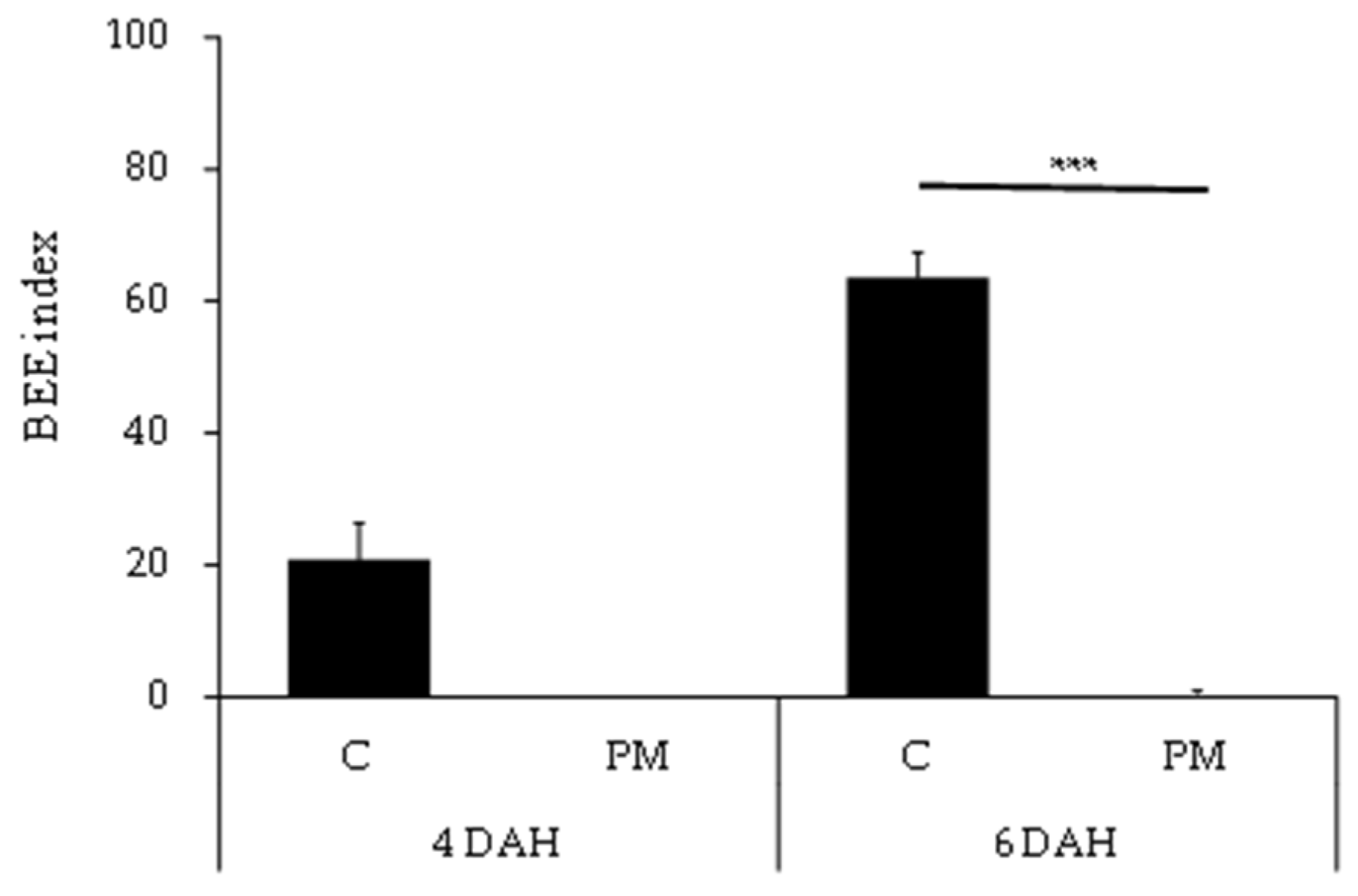

3.2. Packaging Methods and Human-Related Operation Factor on BEE Occurrence

3.3. Changes in Temperature and Humidity Inside Packaging over Time During Distribution

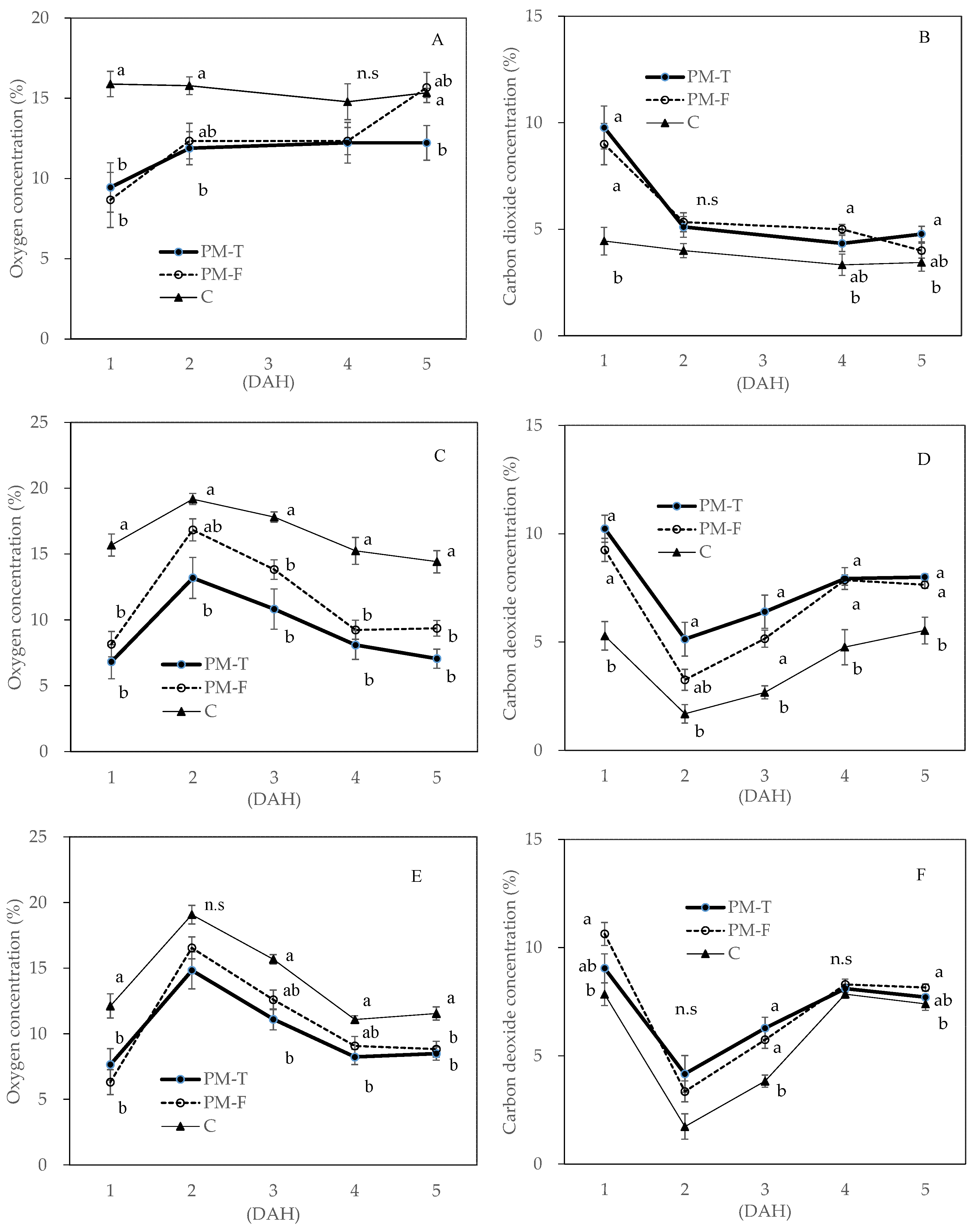

3.4. Changes in Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Concentrations Within the Packaging

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satitmunnaithum, J.; Muroi, H.; Ito, R.; Tashiro, Y.; Hendratmo, A.F.; Tanabata, S.; Sato, T. Cultivation conditions affect the occurrence of blossom-end enlargement in cucumber. Hortic. J. 2022, 91, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, T.; Okada, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Motomura, Y.; Aikawa, T. Postharvest deformation of cucumber fruit associated with water movement and cell wall degradation. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1194, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Oda, H. Studies on the control of physiological disorders in fruit vegetable crops under plastic films. VIII. On the occurrence of abnormal fruits in cucumber plants. (II) On the development of carrot type and bottle gourd type fruits, so-called sakibosori and shiributo fruits in Japan. Res. Rep. Kouchi Univ. 1977, 26, 175–182. Available online: https://kochi.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/5133/files/A026-18.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- IIzawa, R.; Kyono, T. Regional competition and the grading systems among the cucumber-producing areas. Nokei Ronso 1985, 41, 199–227. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2115/10996 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Tashiro, Y.; Sato, T.; Satitmunnaithum, J.; Kinouchi, H.; Li, J.; Tanabata, S. Case study on the use of the leaf-count method for drip fertigation in outdoor cucumber cultivation in reconstructed fields devastated by a tsunami. Agriculture 2021, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Atarashi, R.; Kharisma, A.D.; Arofatullah, N.A.; Tashiro, Y.; Satitmunnaithum, J.; Tanabata, S.; Yamane, K.; Sato, T. Search for Expression Marker Genes That Reflect the Physiological Conditions of Blossom End Enlargement Occurrence in Cucumber. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazuke, A.; Asayama, M. Expression of CsSEF1 gene encoding putative CCCH zinc finger protein is induced by defoliation and prolonged darkness in cucumber fruit. Planta 2013, 237, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, A.A.; Zagory, D.; Kerbel, E.L.; Wang, C.Y. Modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1989, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, B.; Ozer, M.H.; Uylaser, V.; Karaman, B. The effect of low oxygen and high carbon dioxide on storage and pickle production of pickling cucumbers cv. ‘Octobus’. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irtwange, S.V. Application of modified atmosphere packaging and related technology in postharvest handling of fresh fruits and vegetable. Agric. Eng. Int. 2006, 4, 1–13. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstreams/95ed5f37-a85a-4ec7-a0c3-1f193030d8fc/download (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Manjunatha, M.; Anurag, R.K. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging and storage conditions on quality characteristics of cucumber. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3470–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, M.H.; Akbudak, B.; Uylaser, V.; Tamer, E. The effect of controlled atmosphere storage on pickle production from pickling cucumbers cv. ‘Troy’. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chaurasia, S.N.S.; Sharma, S.; Behera, T.K. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) on quality and shelf-life of cucumber during cold storage. Indian. J. Hortic. 2024, 81, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Furuno, S.; Saito, K.; Suzuki, K. Studies on the generation factor of apex enlargement in cucumber fruits during the transportation and control method. Bull. Yamagata Hort. Res. 2005, 17, 39–45. Available online: https://agriknowledge.affrc.go.jp/RN/2030712544.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Okabayashi, H. Effect of storage temperature, fruit shape and modified atmosphere packaging on apex enlargement in cucumber fruits. Bull. Kochi Agric. Res. Cent. 2001, 10, 11–19. Available online: https://agriknowledge.affrc.go.jp/RN/2030630039.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Matsumoto, M.; Okada, I. Studies on the top swelling phenomenon “Sakibutori” of cucumber fruit after harvest. Bull. Tonami Hortic. Branch. Sta 1979, 15, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, I. Modified atmosphere packaging of vegetables with high performance plastic film. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. 1998, 45, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Abe, K.; Chachin, K. Effect of packaging with porous-mineral mixed plastic films on keeping quality of several vegetables. J. Jpn. Soc. Cold Preserv. Food 1990, 16, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuma, Y.; Murata, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Nishihara, A.; Hori, Y. Dormer Strawberry Transportation Tests in Refrigerator-truck for 700 Kilometer. JSAM 1970, 31, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoyemi, F.F.; Esua, O.J.; Latifah, S.Y.; Iqbal, M.T.; Tan, C.P. Effects of compostable packaging and perforation rates on cucumber quality during extended shelf life and simulated farm-to-fork supply-chain conditions. Foods 2021, 10, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhall, R.K.; Sharma, S.R.; Mahajan, B.V.C. Effect of shrink wrap packaging for maintaining quality of cucumber during storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.C.N.; Nicometo, M.; Emond, J.P.; Melis, R.B.; Uysal, I. Improvement in fresh fruit and vegetable logistics quality: Berry logistics field studies. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 372, 20130307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, W.; Brecht, J.K.; Nunes, M.C.N.; Emond, J.P. Quality of strawberries shipped by truck from California to Florida as influenced by postharvest temperature management practices. Hortic. Technol. 2011, 21, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, K.; Nakano, K. Optimal design of modified atmosphere packaging for alleviating chilling injury in cucumber fruit. Environ. Control Biol. 2014, 52, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srilaong, V.; Tatsumi, Y. Changes in respiratory and antioxidative parameters in cucumber fruit (Cucumis sativus L.) stored under high and low oxygen concentrations. Hortic. J. 2003, 72, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Qi, L. Modified atmosphere packaging alleviates chilling injury in cucumbers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997, 10, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsch, R.T.; Slaughter, D.C.; Craig, W.L.; Thompson, J.F. Vibration of fresh fruits and vegetables during refrigerated truck transport. ASABE 1993, 36, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirama, N.; Mizusawa, H.; Azuhata, F.; Matsuura, S. Culture methods to reduce the occurrence of the bottle-gourd-shaped fruits in the greenhouse of fall-cropped cucumber plants. Hortic. Res. 2007, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.N.; Brecht, J.K.; Morais, A.M.M.B.; Sargent, S.A. Physical and chemical quality characteristics of strawberries after storage are reduced by a short delay to cooling. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1995, 6, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.M.; Lee, S.; Lee, W.H.; Cho, B.K.; Lee, S.H. Effect of vibration stress on quality of packaged grapes during transportation. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2018, 11, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Law, C.L.; Ma, Y. Effect of vibration and broken cold chain on the evolution of cell wall polysaccharides during fruit cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) shriveling under simulated transportation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 38, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheka, L.; Spelt, E.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J.; Luning, P.A. Exploration of logistics and quality control activities in view of context characteristics and postharvest losses in fresh produce chains: A case study for tomatoes. Food Control 2017, 77, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, F.F.; Adegbola, J.A.; Bamishaiye, E.I.; Daura, A.M. Assessment of post-harvest challenges of small scale farm holders of tomotoes, bell and hot pepper in some local government areas of Kano State, Nigeria. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2010, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewfelt, R.L.; Prussia, S.E.; Jordan, J.L.; Hurst, W.C.; Resurreccion, A.V.A. A systems analysis of postharvest handling of fresh snap beans. Hortic. Sci. 1986, 21, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwate Prefecture. Iwate Prefecture Standard Shipping Standards for Fruit and Vegetables. 2018. Available online: https://www.pref.iwate.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/072/910/syukkakikakusyuu.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Arofatullah, N.A. Introduction of open platform ubiquitous environment control system (UECS-Pi) for greenhouse management and agricultural research activities. In Ag-ESD Symposium 2016; Agricultural and Forestry Research Center, University of Tsukuba: Tsukuba, Japan, 2016; p. 31. Available online: http://www.nourin.tsukuba.ac.jp/~agesd/pdf/agesd2016_summary.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Toita, H.; Kobayashi, K. Construction of an open platform (UECS-Pi) for autonomous distributed environment measurement and control system using Raspberry Pi, a general-purpose substrate for education. Agric. Inf. Res. 2016, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaks, I.L.; Morris, L.L. Respiration of cucumber fruits associated with physiological injury at chilling temperatures. Plant Physiol. 1956, 31, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, S.; Villeneuve, S.; Mondor, M.; Uysal, I. Time-temperature management along the food cold chain: A review of recent developments. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndraha, N.; Hsiao, H.I.; Vlajic, J.; Yang, M.F.; Lin, H.T.V. Time-temperature abuse in the food cold chain: Review of issues, challenges, and recommendations. Food Control 2018, 89, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.N.; Emond, J.P.; Brecht, J.K. Brief deviations from set point temperatures during normal airport handling operations negatively affect the quality of papaya (Carica papaya) fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 41, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, U.L.; Mditshwa, A. A review on the role of packaging in securing food system: Adding value to food products and reducing losses and waste. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar]

| Days After Harvest | 2019 | 2020 | Time | Event | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 0 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/17 | 8/24 | 15:00–17:00 | Harvest |

| 17:00–22:00 | Packaging, storage at the shed | |||||

| 1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/18 | 8/25 | 7:00–9:30 | Departure from the shed to the collection point |

| 9:30–12:00 | Arrival at a pre-cooled warehouse at the collection point | |||||

| 2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/19 | 8/26 | 9:30–10:30 | Shipping out to load onto pallets |

| 10:30–12:30 | Loading the pallets onto a truck, departure | |||||

| 20:00–22:00 | Arrival at Tokyo Central Wholesale Market, Ota Market | |||||

| 22:30–02:00 | Arrival at Ibaraki University, start of storage | |||||

| Harvest Date | Packaging Method | 4 DAH | 6 DAH | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | Mean | SD | Producer | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| X | Y | Z | X | Y | Z | ||||||||

| 2 August | PM-T | 5.7 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 2.7 | a | 2.9 | 9.6 | 2.9 | 6.7 | 6.4 | a | 3.3 |

| PM-F | 9.6 | 13.5 | 0.9 | 8.0 | a | 6.5 | 17.4 | 23.7 | 14.4 | 18.5 | b | 4.8 | |

| C-F | 25.3 | 26.7 | 13.7 | 21.9 | b | 7.1 | 34.7 | 37.3 | 25.5 | 32.5 | c | 6.2 | |

| mean | 13.6 | 13.4 | 5.7 | 10.9 | 4.5 | 20.6 | 21.3 | 15.5 | 19.1 | 3.2 | |||

| n.s | n.s | ||||||||||||

| SD | 10.4 | 13.3 | 7.0 | 9.9 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 9.4 | 13.1 | |||||

| 17 August | PM-T | 1.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 1.2 | a | 1.0 | 8.3 | 0.5 | 12.4 | 6.7 | a | 6.1 |

| PM-F | 6.9 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 3.2 | ab | 3.3 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 10.5 | 10.9 | ab | 5.6 | |

| C-F | 21.8 | 4.7 | 17.8 | 14.7 | b | 8.9 | 30.7 | 14.3 | 26.2 | 23.5 | b | 8.5 | |

| mean | 9.9 | 1.9 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 18.5 | 6.7 | 16.4 | 13.7 | 6.3 | |||

| a | b | b | n.s | ||||||||||

| SD | 10.6 | 2.4 | 9.0 | 7.3 | 11.3 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 8.7 | |||||

| 24 August | PM-T | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 | a | 2.7 | 27.3 | 0.7 | 3.8 | 10.6 | a | 14.6 |

| PM-F | 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | a | 1.1 | 15.1 | 7.1 | 5.3 | 9.2 | a | 5.2 | |

| C-F | 9.3 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | b | 3.1 | 26.7 | 19.1 | 17.6 | 21.1 | b | 4.9 | |

| mean | 5.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 23.0 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 13.6 | 8.1 | |||

| n.s | a | b | b | ||||||||||

| SD | 3.9 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 6.5 | |||||

| ANOVA | packing method | *** | ** | ||||||||||

| harvest date | *** | *** | |||||||||||

| individual | *** | *** | |||||||||||

| packing method × harvest date | *** | * | |||||||||||

| packing method × individual | * | ** | |||||||||||

| harvest date × individual | n.s | n.s | |||||||||||

| packing method × harvest date × individual | n.s | n.s | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tashiro, Y.; Mochizuki, K.; Uji, E.; Ito, R.; Quyen, T.M.; Arofatullah, N.A.; Kharisma, A.D.; Tanabata, S.; Yamane, K.; Sato, T. Evaluation of Factors Affecting Cucumber Blossom-End Enlargement Occurrence During Commercial Distribution. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121476

Tashiro Y, Mochizuki K, Uji E, Ito R, Quyen TM, Arofatullah NA, Kharisma AD, Tanabata S, Yamane K, Sato T. Evaluation of Factors Affecting Cucumber Blossom-End Enlargement Occurrence During Commercial Distribution. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121476

Chicago/Turabian StyleTashiro, Yuki, Kohei Mochizuki, Erika Uji, Rina Ito, Tran Mi Quyen, Nur Akbar Arofatullah, Agung Dian Kharisma, Sayuri Tanabata, Kenji Yamane, and Tatsuo Sato. 2025. "Evaluation of Factors Affecting Cucumber Blossom-End Enlargement Occurrence During Commercial Distribution" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121476

APA StyleTashiro, Y., Mochizuki, K., Uji, E., Ito, R., Quyen, T. M., Arofatullah, N. A., Kharisma, A. D., Tanabata, S., Yamane, K., & Sato, T. (2025). Evaluation of Factors Affecting Cucumber Blossom-End Enlargement Occurrence During Commercial Distribution. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121476