Antifungal Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Y48 Postbiotics Combined with Potassium Sorbate in Bread

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Preparation and Lyophilization of Postbiotics

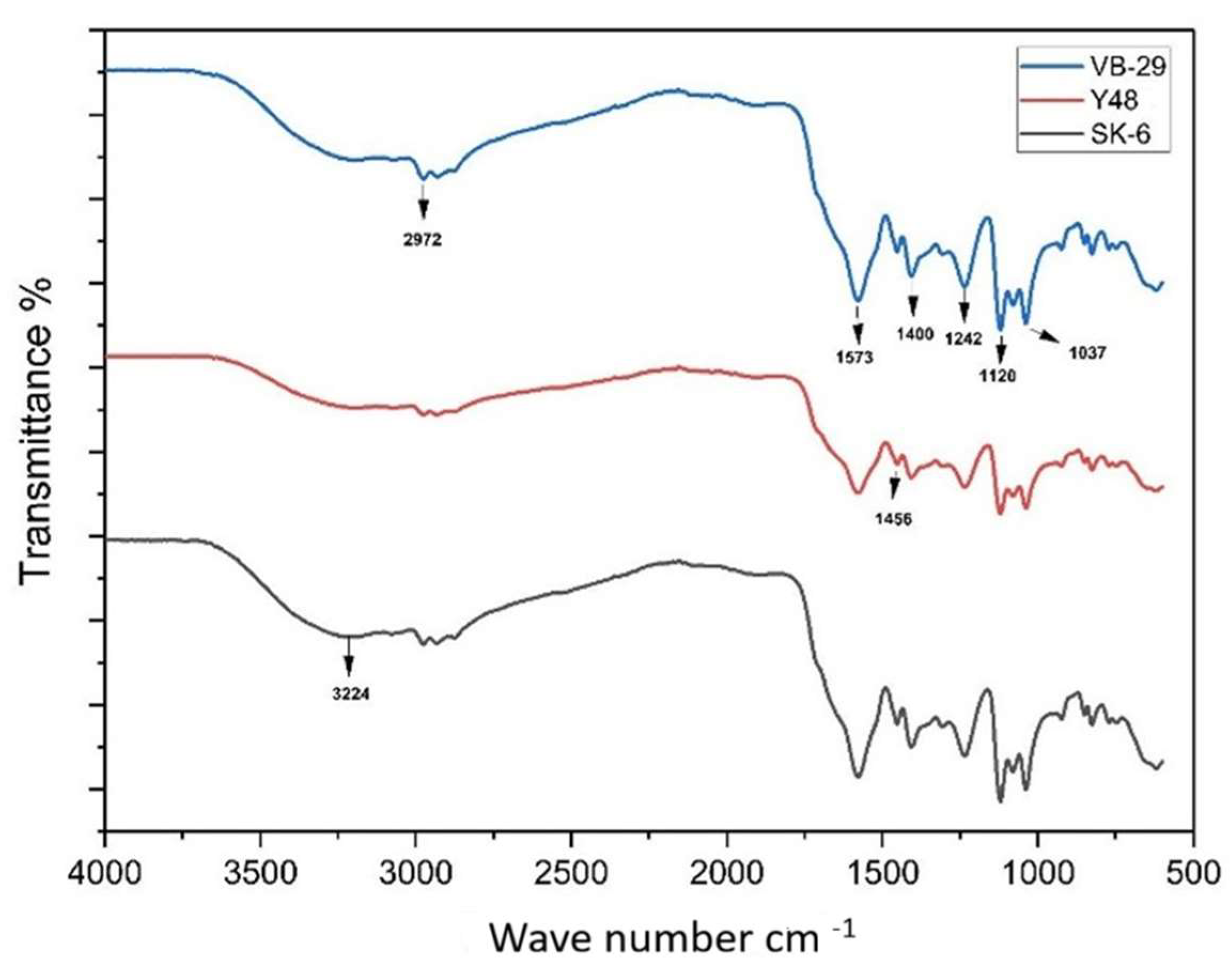

2.3. Characterization of Postbiotics by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

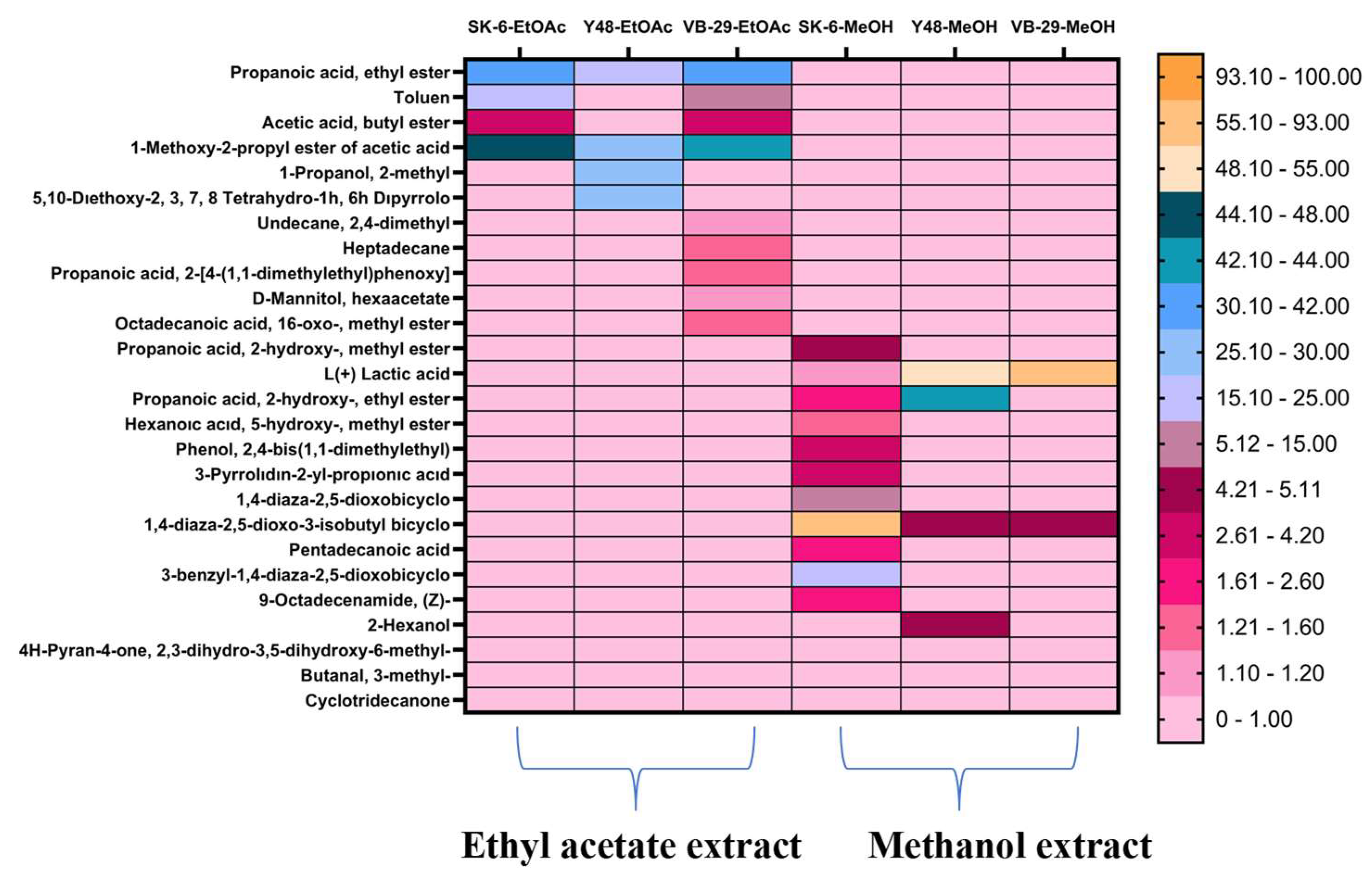

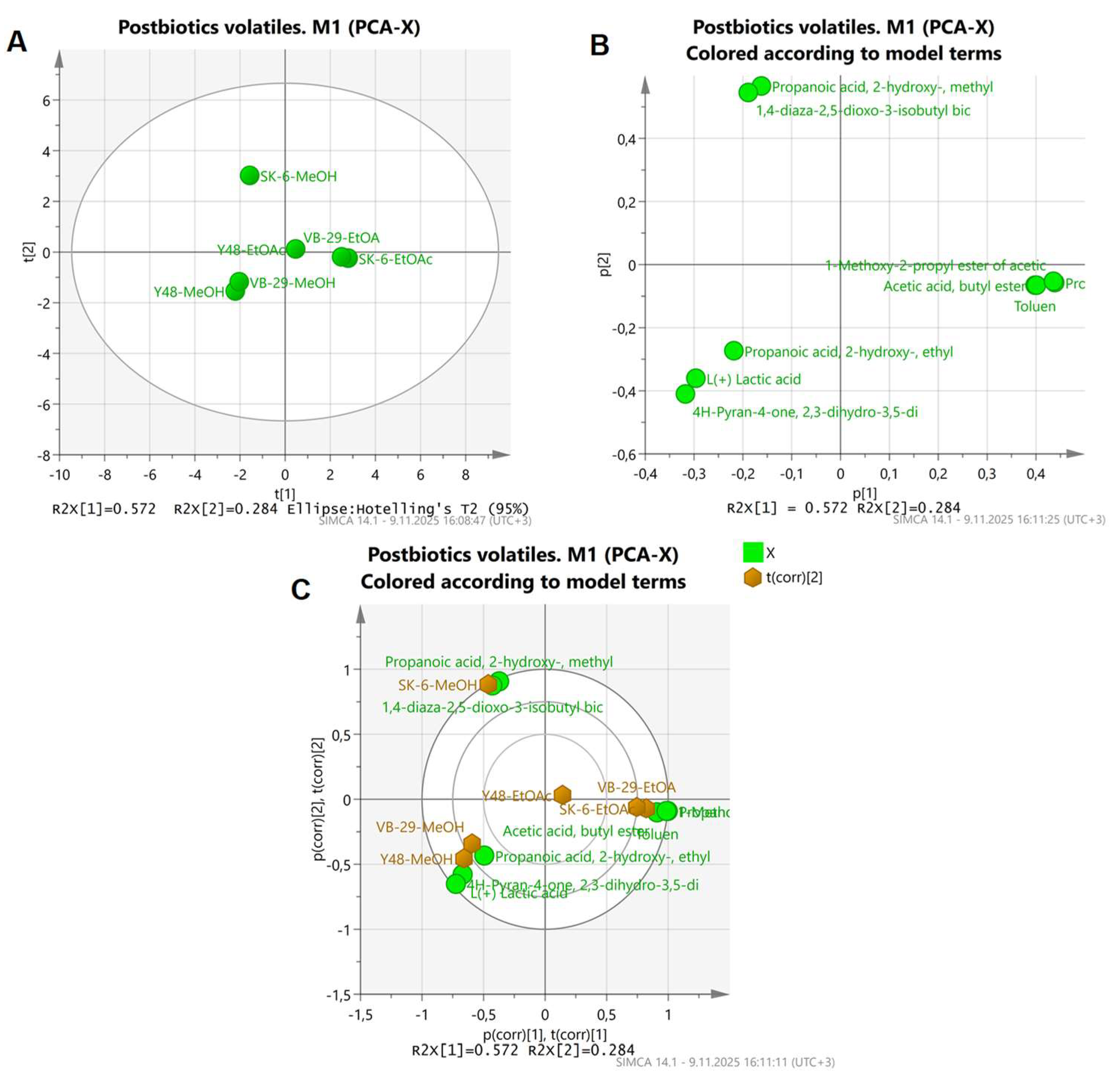

2.4. Volatile Compound Profile of Postbiotics

2.5. Evaluation of Postbiotics Antifungal Activity Using Disk Diffusion Assay

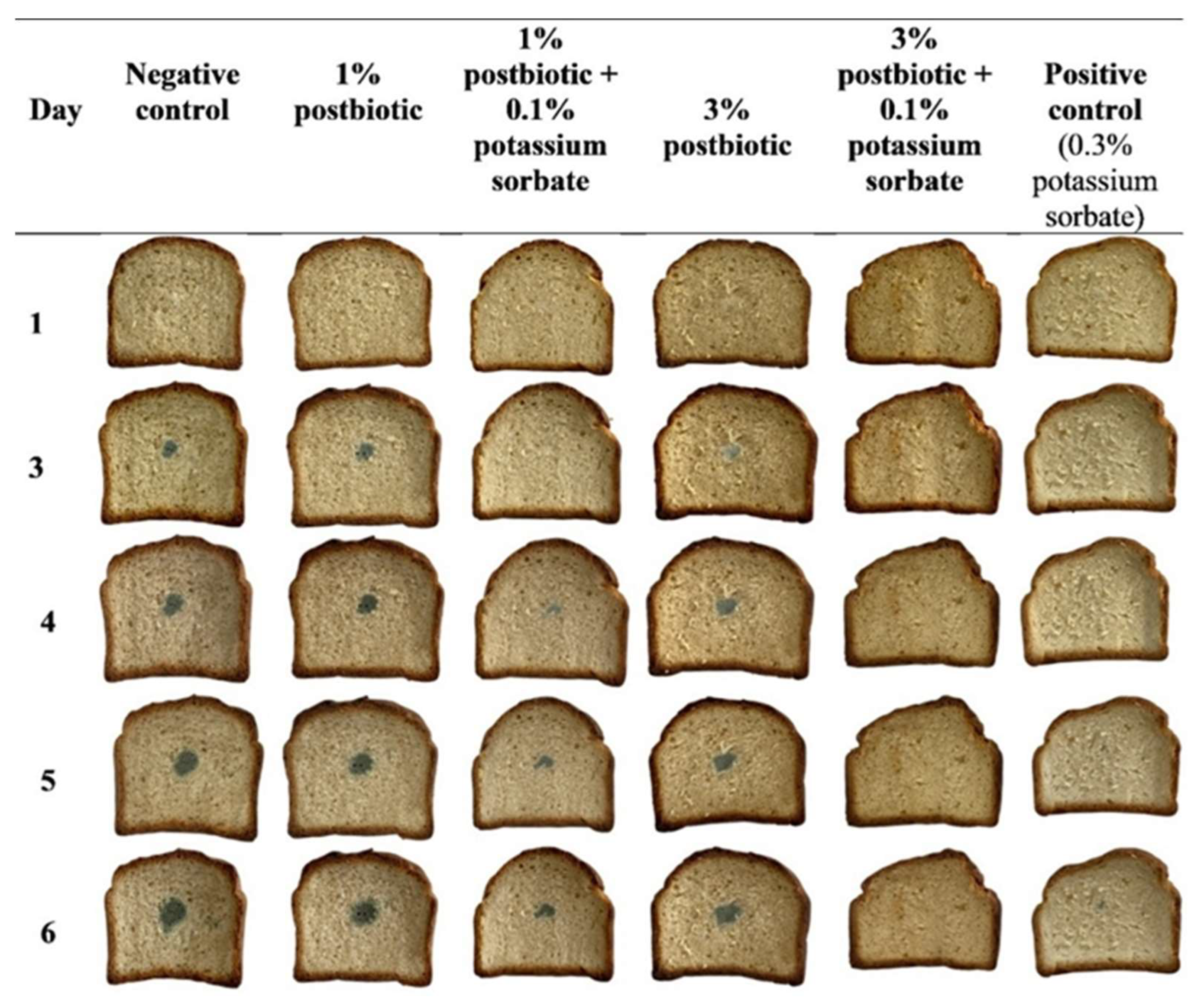

2.6. Production of Bread Samples and Antifungal Challenge Test

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Postbiotics by FTIR Analysis

3.2. Volatile Compound Profiles of Postbiotics

3.3. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Postbiotics

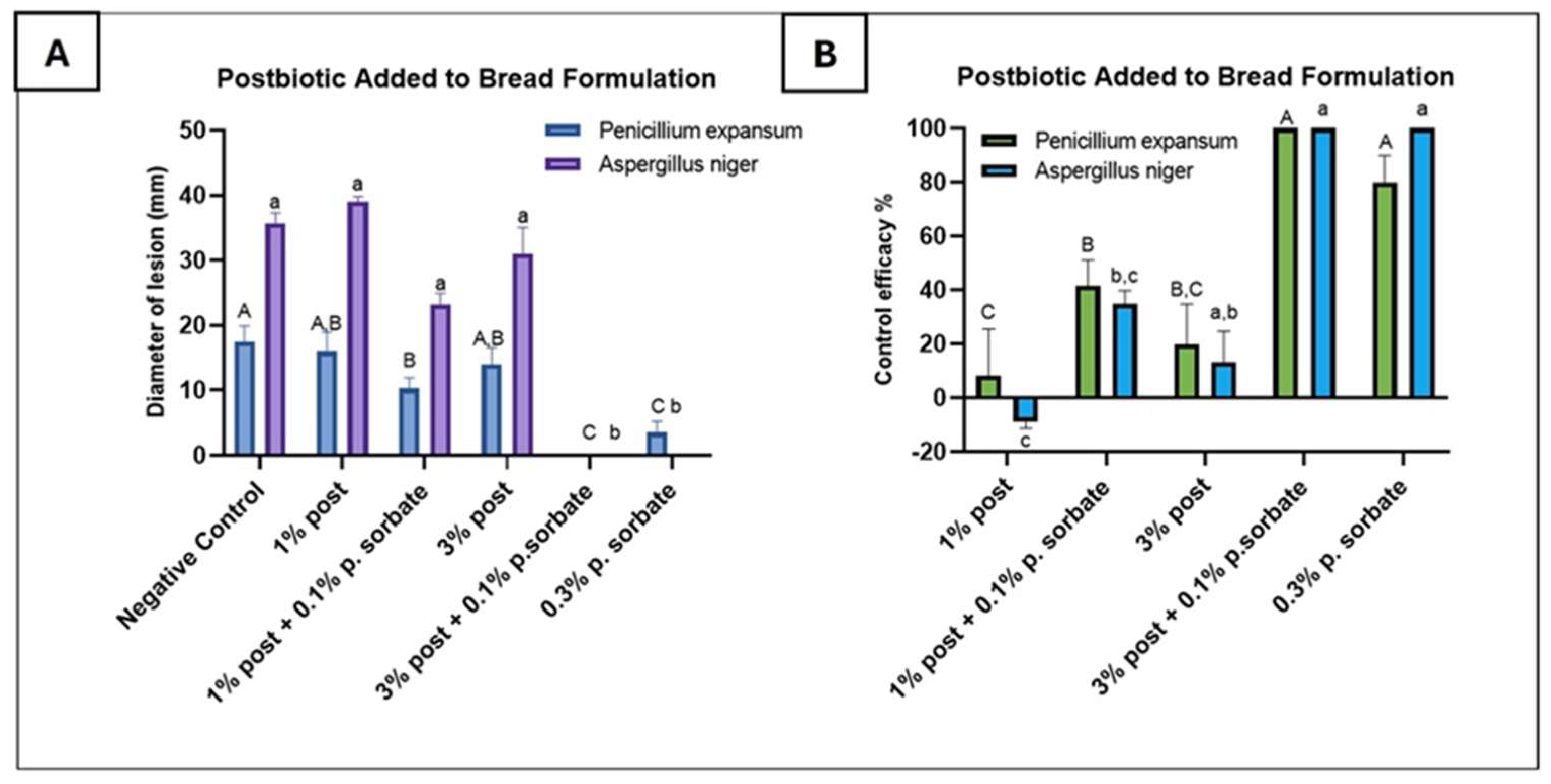

3.4. Antifungal Activity Test of Postbiotics Applied for Bread Production

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P1 | P. concentricum |

| P2 | P. expansum |

| P3 | P. chrysogenum |

| A1 | A. niger |

| A2 | A. parasiticus |

| F1 | Fusarium spp. |

| AA | Alternaria alternata |

| Y48-EtOAc | Y48 postbiotic extracted with ethyl acetate |

| SK-6-EtOAc | SK-6 postbiotic extracted with ethyl acetate |

| VB-29-EtOAc | VB-29 postbiotic extracted with ethyl acetate; |

| Y48-MeOH | Y48 postbiotic extracted with methanol |

| SK-6-MeOH | SK-6 postbiotic extracted with methanol |

| VB-29-MeOH | VB-29 postbiotic extracted with methanol |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Noshirvani, N.; Abolghasemi Fakhri, L. Advances in Extending the Microbial Shelf-Life of Bread and Bakery Products Using Different Technologies: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, A.; Dobrowolska, B.; Dziugan, P.; Motyl, I.; Liszkowska, W.; Rydlewska-Liszkowska, I.; Berłowska, J. Bread consumption trends in Poland: A socio-economic perspective and factors affecting current intake. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7776–7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerez, C.L.; Torino, M.I.; Rollán, G.; de Valdez, G.F. Prevention of bread mould spoilage by using lactic acid bacteria with antifungal properties. Food Control. 2009, 20, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Ríos, K.; Montoya-Estrada, C.N.; Martínez-Miranda, M.M.; Hurtado Cortés, S.; Taborda-Ocampo, G. Physicochemical treatments for the reduction of aflatoxins and Aspergillus niger in corn grains (Zea mays). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3707–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán, J.; Kilasoniya, A. Integration of Postbiotics in Food Products through Attenuated Probiotics: A Case Study with Lactic Acid Bacteria in Bread. Foods 2024, 13, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Jamil, K. Studies on the shelf life enhancement of traditional leavened bread. Pak. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 45, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, J.; Xie, Y.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yao, W. Synergistic inhibition effect of citral and eugenol against Aspergillus niger and their application in bread preservation. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, C.B.; Lemos, J.G.; Gasperini, A.M.; Stefanello, A.; Garcia, M.V.; Copetti, M.V. Efficacy of weak acid preservatives on spoilage fungi of bakery products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 374, 109723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, K.I.; Nielsen, P.V. Effect of weak acid preservatives on growth of bakery product spoilage fungi at different water activities and pH values. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 95, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brul, S.; Coote, P. Preservative agents in foods: Mode of action and microbial resistance mechanisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, B.; Gursoy, M.; Kiran, F.; Loimaranta, V.; Söderling, E.; Gursoy, U.K. Postbiotics of the Lactiplantibacillus plantarum EIR/IF-1 strain show antimicrobial activity against oral microorganisms with pH adaptation capability. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 1442–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İncili, G.K.; Karatepe, P.; Akgöl, M.; Güngören, A.; Koluman, A.; İlhak, O.İ.; Kanmaz, H.; Kaya, B.; Hayaloğlu, A.A. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria postbiotics, evaluation in-vitro antibacterial effect, microbial and chemical quality on chicken drumsticks. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydaryinia, A.; Veissi, M.; Sadadi, A. A comparative study of the effects of the two preservatives, sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate on Aspergillus niger and Penicillium notatum. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2011, 4, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- López-Malo, A.; Barreto-Valdivieso, J.; Palou, E.; San Martín, F. Aspergillus flavus growth response to cinnamon extract and sodium benzoate mixtures. Food Control 2007, 18, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Erten, T.; Vurmaz, M.; İspirli, H.; Şimşek, Ö.; Dertli, E. Comparison of the probiotic characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) isolated from sourdough and infant feces. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Şengül, M.; Dertli, E. Lactobacillus spp. Tarafından Üretilen Postbiyotiklerin Gıdalarda Biyokoruyucu Olarak Kullanımı: Probiyotiklerden Postbiyotiklere Geçiş. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 1562–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Ediş, K.K.; Karaaslan, N.; Ortakci, F.; Şengül, M.; Dertli, E. Functional Properties of Postbiotics Derived From Liquorilactobacillus hordei SK-6 for Bio-Decontamination in Ready-To-Eat Lettuce. J. Food Saf. 2025, 45, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Gianni, M.L.; Rescigno, M. Can postbiotics represent a new strategy for NEC? Probiotics and Child Gastrointestinal Health: Advances in Microbiology. Infect. Dis. Public Health 2019, 10, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zeng, X.; Fu, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, M. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: A comprehensive review of its antifungal and anti-mycotoxic effects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjan, P.; Sakpetch, P. Effect of antifungal compounds secreted by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 124 against Aspergillus flavus and Penicillium sp. and its application in Kaeng-Tai-Pla-Haeng to extend the shelf life. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 5376–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddik, H.A.; Bendali, F.; Gancel, F.; Fliss, I.; Spano, G.; Drider, D. Lactobacillus plantarum and its probiotic and food potentialities. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 9, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwozor, N.C. Antagonistic activity of lactic acid bacteria bioactive molecules against fungi isolated from onion (Allium cepa). EC Microbiol. 2019, 15, 318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva Salas, M.; Thierry, A.; Lemaitre, M.; Garric, G.; Harel-Oger, M.; Chatel, M.; Lê, S.; Mounier, J.; Valence, F. Antifungal activity of lactic acid bacteria combinations in dairy mimicking models and their potential as bioprotective cultures in pilot scale applications. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delavenne, E.; Mounier, J.; Déniel, F.; Barbier, G.; Le Blay, G. Biodiversity of antifungal lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw milk samples from cow, ewe and goat over one-year period. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 155, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Manjarres, J.J.; Ramírez, C.; Bolívar, G. Use of an exopolysaccharide-based edible coating and lactic acid bacteria with antifungal activity to preserve the postharvest quality of cherry tomato. LWT 2021, 151, 112225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, A.; Naz, G.; Majeed, K.; Mughal, V.; Amjad, K.; Sarwar, A.; Mahmood, S. Investigating the antifungal potential of essential oils from different plants against bread mold contaminants: A Faisalabad, Pakistan perspective. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2024, 2024, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Bashari, M. Shelf life enhancement of bread by utilizing natural and chemical preservatives. Emerg. Chall. Agric. Food Sci. 2023, 8, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Melini, V.; Melini, F. Strategies to extend bread and GF bread shelf-life: From Sourdough to antimicrobial active packaging and nanotechnology. Fermentation 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, A.M.; Marrez, D.A.; Ramadan, A.S.; El-Rashedy, A.A.; Badr, A.N.; Hoppe, K.; Li, H.; He, Z. Antifungal potential of Lactobacillus bioactive metabolites: Synergistic interactions with food preservatives and molecular docking insights. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 2761–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Meng, R.; Bu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, N. Antibacterial effect of caprylic acid and potassium sorbate in combination against Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İspirli, H.; Dertli, E. Isolation and identification of exopolysaccharide producer lactic acid bacteria from Turkish yogurt. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İspirli, H.; Dertli, E. Geleneksel Yollarla Üretilmiş Turşu Örneklerinden Laktik Asit Bakterilerinin İzolasyonu, Moleküler Yöntemler Kullanilarak Tanimlanmasi Ve Bazi Fonksiyonel Özelliklerinin Belirlenmesi. Gıda 2023, 48, 360–380. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbaş, F.; Dertli, E.; Arıcı, M. Prevalence of Clostridium spp. in Kashar cheese and efficiency of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis mix as a biocontrol agents for Clostridium spp. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Mardani, K.; Tajik, H. Characterization and application of postbiotics of Lactobacillus spp. on Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and in food models. LWT 2019, 111, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buncic, S.; Avery, S.M.; Moorhead, S.M. Insufficient antilisterial capacity of low inoculum Lactobacillus cultures on long-term stored meats at 4 C. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1997, 34, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumal, V.; Venkatesan, A. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic effect and purification of bacteriocin from vancomycin susceptible Enterococcus faecalis and its safety evaluation for probiotization. LWT 2017, 78, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, W.; Aida, W.; Sahilah, A.; Maskat, M. Volatile compounds and lactic acid bacteria in spontaneous fermented sourdough. Sains Malays. 2011, 40, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Fan, Y.; Shi, Z. Antifungal activity of eugenol against Botrytis cinerea. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2010, 35, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Fares, C.; Longo, A.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Lactobacillus plantarum with broad antifungal activity as a protective starter culture for bread production. Foods 2017, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh Kumar, B.; Muthumari, B.; Kavitha, M.; John Praveen Kumar, J.K.; Thavamurugan, S.; Arun, A.; Jothi Basu, M. Studies on optimization of sustainable lactic acid production by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens from sugarcane molasses through microbial fermentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Jiang, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y. Antilisterial and physical properties of polysaccharide-collagen films embedded with cell-free supernatant of Lactococcus lactis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Moradi, M.; Tajik, H.; Molaei, R. Potential application of postbiotics metabolites from bioprotective culture to fabricate bacterial nanocellulose based antimicrobial packaging material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, Y.; Moradi, M.; Tajik, H.; Molaei, R. Fabrication of anti-Listeria film based on bacterial cellulose and Lactobacillus sakei-derived bioactive metabolites; application in meat packaging. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Al-Holy, M.; Chang, S.-S.; Huang, Y.; Cavinato, A.G.; Kang, D.-H.; Rasco, B.A. Rapid discrimination of Alicyclobacillus strains in apple juice by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 105, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbagam, D.; Gurusamy, R.; Senthilkumar, B. Physical chemical and biological characterization of a new bacteriocin produced by Bacillus cereus NS02. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2013, 6, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, S.; Mokarram, R.R.; Khiabani, M.S.; Bari, M.R.; Khaledabad, M.A. Characterization of antimicrobial peptides produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 and Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 and their inhibitory effect against foodborne pathogens. LWT 2022, 153, 112449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, E.U.; Polat, S.; Erginkaya, Z.; Konuray, G. Investigation of synergistic antibacterial effect of organic acids and ultrasound against pathogen biofilms on lettuce. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Molaei, R.; Guimarães, J.T. A review on preparation and chemical analysis of postbiotics from lactic acid bacteria. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2021, 143, 109722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Arena, M.P.; Fiocco, D.; Capozzi, V.; Drider, D.; Spano, G. Lactobacillus plantarum with broad antifungal activity: A promising approach to increase safety and shelf-life of cereal-based products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 247, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Bello, F.; Clarke, C.; Ryan, L.; Ulmer, H.; Schober, T.; Ström, K.; Sjögren, J.; Van Sinderen, D.; Schnürer, J. Improvement of the quality and shelf life of wheat bread by fermentation with the antifungal strain Lactobacillus plantarum FST 1.7. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 45, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, O.M.; Al-Gamal, M.S.; Ibrahim, G.A.; Dabiza, N.M.; Salem, S.S.; El-Ssayad, M.F.; Youssef, A.M. Evaluation and characterization of some protective culture metabolites in free and nano-chitosan-loaded forms against common contaminants of Egyptian cheese. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 115094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelyuntha, W.; Chaiyasut, C.; Kantachote, D.; Sirilun, S. Organic acids and 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol: Major compounds of Weissella confusa WM36 cell-free supernatant against growth, survival and virulence of Salmonella Typhi. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, F.; İspirli, H.; Kurnaz, A.A.; Yilmaz, M.T.; Dertli, E. Antimicrobial and functional properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from sourdoughs. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambang, Z.; Chewachong, G.; Ngatsi, P.Z.; Nganti, D.M.; Tueguem, W.K.; Heu, A.; Dooh, J.P.N.; Sale, C.E. Efficacy of methanolic and aqueous extracts of Thevetia peruviana (pers.) K. Schum on growth of Phytophthora colocasiae Racib, causal agent of taro late blight in Cameroon. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2021, 24, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboussi, S.; Ambang, Z.; Ndogho, A.; Dooh, J.; Essouma, F. In vitro antifungal potential of aqueous seeds extracts of Azadirachta indica and Thevetia peruviana against Phytophthora megakarya in Cameroon. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2016, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerez, C.; Carbajo, M.; Rollán, G.; Torres Leal, G.; Font de Valdez, G. Inhibition of citrus fungal pathogens by using lactic acid bacteria. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, M354–M359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Suo, H.; Hamdy, A.M.; Song, J. Antifungal effect of metabolites from a new strain Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LPP703 isolated from naturally fermented Yak Yogurt. Foods 2023, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Rather, I.; Seo, B.; Rejish Kumar, V.; Choi, U.H.; Choi, K.H.; Lim, J.; Park, Y.H. Isolation and characterization of a proteinaceous antifungal compound from Lactobacillus plantarum YML007 and its application as a food preservative. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.; Shen, F.; Wang, H. A new high phenyl lactic acid-yielding Lactobacillus plantarum IMAU10124 and a comparative analysis of lactate dehydrogenase gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 356, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, T.d.M.; Luz, C.; Torrijos, R.; Quiles, J.M.; Luciano, F.B.; Mañes, J.; Meca, G. Potential application of lactic acid bacteria to reduce aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 occurrence on corn kernels and corn ears. Toxins 2019, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornachandra Rao, K.; Deepthi, B.; Rakesh, S.; Ganesh, T.; Achar, P.; Sreenivasa, M. Antiaflatoxigenic potential of cell-free supernatant from Lactobacillus plantarum MYS44 against Aspergillus parasiticus. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizeikiene, D.; Juodeikiene, G.; Paskevicius, A.; Bartkiene, E. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against pathogenic and spoilage microorganism isolated from food and their control in wheat bread. Food Control. 2013, 31, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falguni, P.; Shilpa, V.; Mann, B. Production of proteinaceous antifungal substances from Lactobacillus brevis NCDC 02. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2010, 63, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-J.; Chao, C.-J.; Chang, H.-Y.; Wu, P.-C. The effects of evaporating essential oils on indoor air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fandos, E.; Martínez-Laorden, A.; Perez-Arnedo, I. Efficacy of combinations of lactic acid and potassium sorbate against Listeria monocytogenes in chicken stored under modified atmospheres. Food Microbiol. 2021, 93, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atfaoui, K.; Lebrazi, S.; Raffak, A.; Chafai, Y.; Kabous, K.E.; Fadil, M.; Ouhssine, M. Impact of Selected Starter-Based Sourdough Types on Fermentation Performance and Bio-Preservation of Bread. Fermentation 2025, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L.; Dal Bello, F.; Arendt, E. The use of sourdough fermented by antifungal LAB to reduce the amount of calcium propionate in bread. International. J. Food Microbiol 2008, 125, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.P.; Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Exploration of the microbial biodiversity associated with north apulian sourdoughs and the effect of the Increasing Number of Inoculated Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains on the Biocontrol against Fungal Spoilage. Fermentation 2019, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.O.N.; Buttke, T.M. Effects of alcohols on micro-organisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 1985, 25, 253–300. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Marwaha, R.K.; Narasimhan, B. Synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation and QSAR studies of propionic acid derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S881–S893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, J.; Gu, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, J. Effects of lactic acid bacteria fermentation on the bioactive composition, volatile compounds and antioxidant activity of Huyou (Citrus aurantium ‘Changshan-huyou’) peel and pomace. Food Qual. Saf. 2023, 7, fyad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.F.; Khan, I.H.; Javaid, A. Detection of Compounds and Efficacy of N-Butanol Stem Extract of Chenopodium murale L. Against Fusarium Oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2022, 51, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajivgandhi, G.N.; Ramachandran, G.; Kanisha, C.C.; Li, J.-L.; Yin, L.; Manoharan, N.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M. Anti-biofilm compound of 1,4-diaza-2, 5-dioxo-3-isobutyl bicyclo [4.3.0] nonane from marine Nocardiopsis sp. DMS 2 (MH900226) against biofilm forming K. pneumoniae. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 3495–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalié, D.; Deschamps, A.; Richard-Forget, F. Lactic acid bacteria–Potential for control of mould growth and mycotoxins: A review. Food Control. 2010, 21, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Postbiotics | P1 | P2 | P3 | A1 | A2 | F1 | AA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK-6 | + | +++ | + | + | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Y48 | + | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| VB-29 | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaya, Y.; Dere, S.; Bozkurt, F.; Devecioglu, D.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Sengul, M.; Dertli, E. Antifungal Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Y48 Postbiotics Combined with Potassium Sorbate in Bread. Fermentation 2025, 11, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120675

Kaya Y, Dere S, Bozkurt F, Devecioglu D, Karbancioglu-Guler F, Sengul M, Dertli E. Antifungal Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Y48 Postbiotics Combined with Potassium Sorbate in Bread. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):675. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120675

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya, Yasemin, Sevda Dere, Fatih Bozkurt, Dilara Devecioglu, Funda Karbancioglu-Guler, Mustafa Sengul, and Enes Dertli. 2025. "Antifungal Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Y48 Postbiotics Combined with Potassium Sorbate in Bread" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120675

APA StyleKaya, Y., Dere, S., Bozkurt, F., Devecioglu, D., Karbancioglu-Guler, F., Sengul, M., & Dertli, E. (2025). Antifungal Effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Y48 Postbiotics Combined with Potassium Sorbate in Bread. Fermentation, 11(12), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120675