Formulation of PVA Hydrogel Patch as a Drug Delivery System of Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

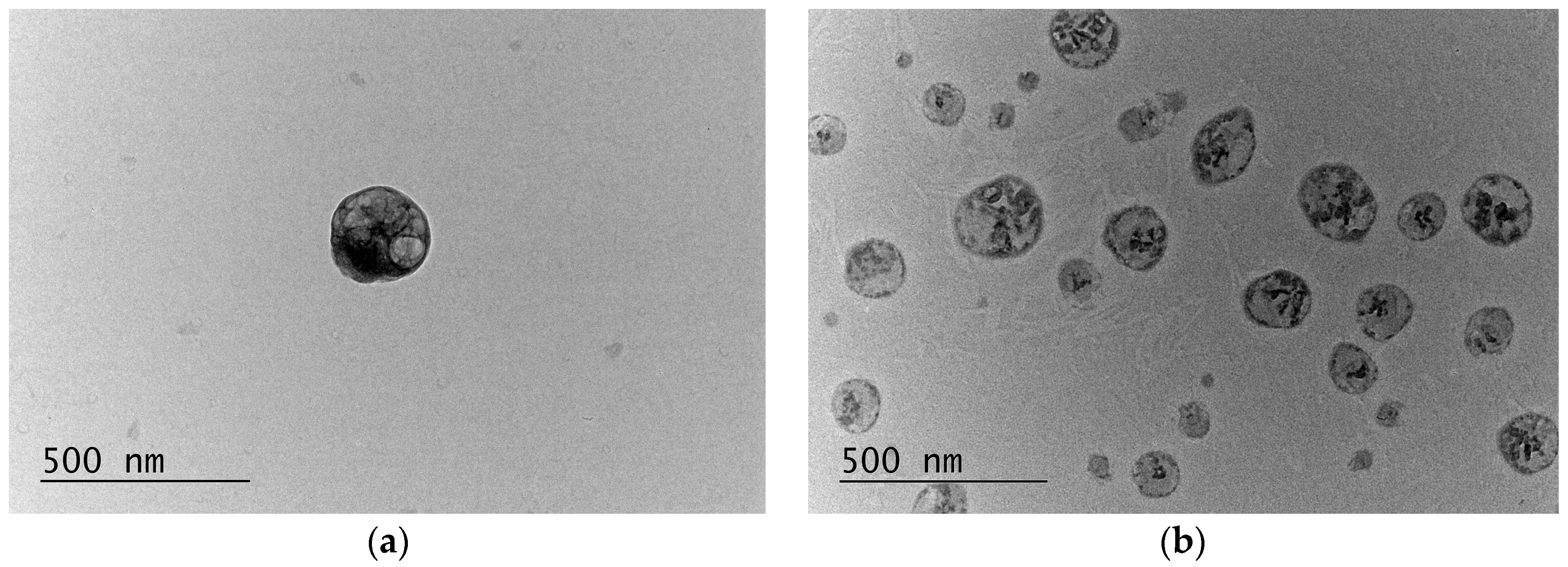

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of the Nanoparticles

2.2. In Vitro Release Study of CurcAlbNPs

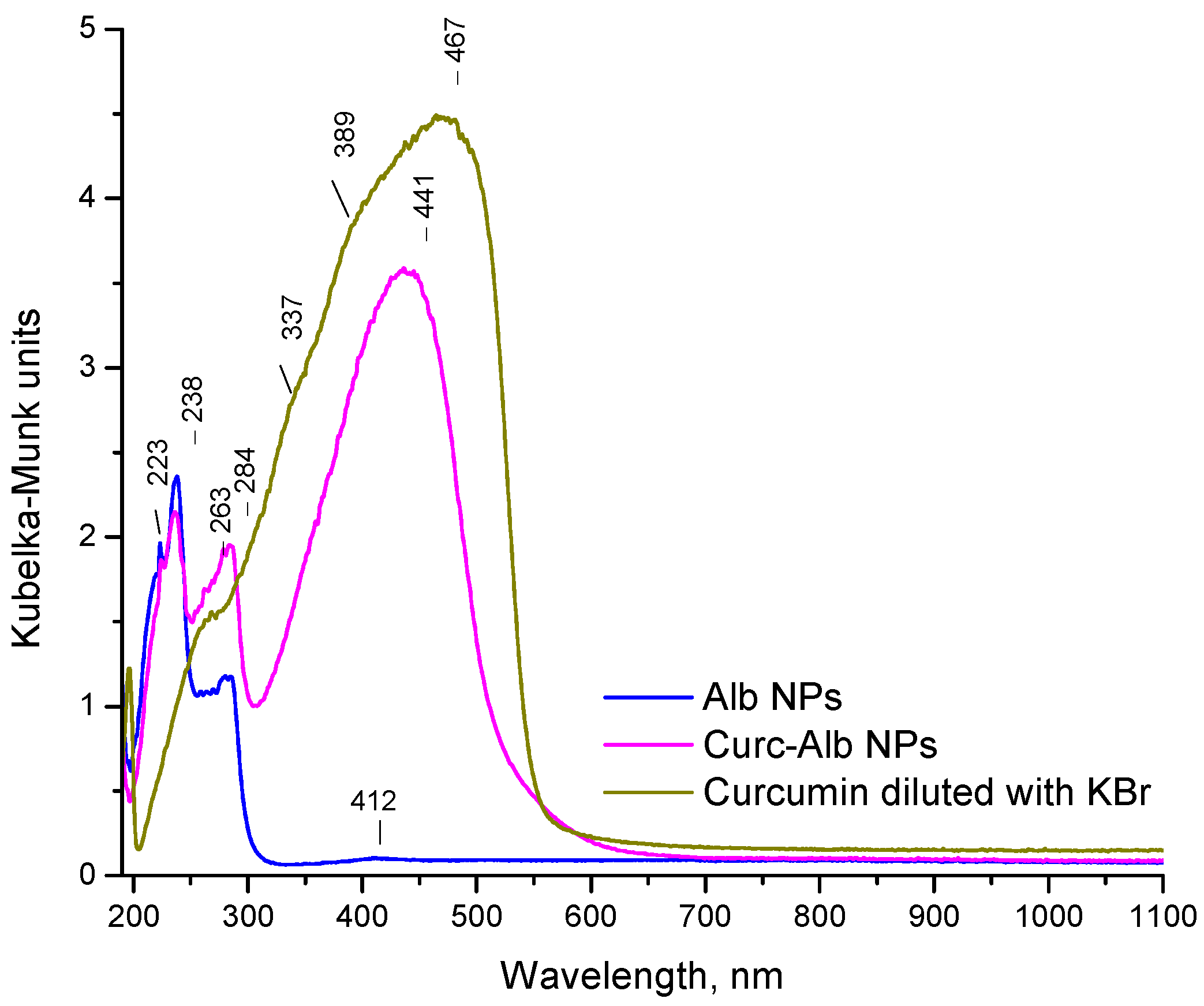

2.3. Diffuse-Reflectance UV–Vis and XRD Analyses

2.4. DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl) and ABTS (2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid)) Tests

2.5. In Vitro Model of Oxidative Stress

2.6. Mechanical Properties of the Patches

2.7. In Vitro Release Study of Curc and CurcAlbNPs Loaded in the Patch

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Empty (AlbNPs) and Curcumin-Loaded (CurcAlbNPs) Albumin Nanoparticles

4.3. Characterization of the Nanoparticles

4.4. In Vitro Release Studies

4.5. Molecular Docking and Dynamics

4.6. DPPH and ABTS Studies

4.7. In Vitro Model of Oxidative Stress

4.8. Preparation of PVA Patches Containing Curcumin-Loaded Nanoparticles

4.9. Characterization of the Mechanical Properties of PVA Patches

4.10. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bickers, D.R.; Athar, M. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Skin Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouba, K.J.; Hamadeh, H.K.; Amin, R.P.; Germolec, D.R. Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Skin Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002, 4, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, K.; Tsuruta, D. What Are Reactive Oxygen Species, Free Radicals, and Oxidative Stress in Skin Diseases? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Subba, D.P.; Seema; Firdous, S.M.; Odeku, O.A.; Kumar, S.; Sindhu, R.K. Antioxidants in Skin Disorders. In Antioxidants; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 551–572. ISBN 978-1-394-27057-6. [Google Scholar]

- Čižmárová, B.; Hubková, B.; Tomečková, V.; Birková, A. Flavonoids as Promising Natural Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Selected Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zaid, N.A.; Sekar, M.; Bonam, S.R.; Gan, S.H.; Lum, P.T.; Begum, M.Y.; Mat Rani, N.N.I.; Vaijanathappa, J.; Wu, Y.S.; Subramaniyan, V.; et al. Promising Natural Products in New Drug Design, Development, and Therapy for Skin Disorders: An Overview of Scientific Evidence and Understanding Their Mechanism of Action. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 16, 23–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liczbiński, P.; Michałowicz, J.; Bukowska, B. Molecular mechanism of curcumin action in signaling pathways: Review of the latest research. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Lin, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, G.; Feng, Z. Research progress on the mechanism of curcumin anti-oxidative stress based on signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1548073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.; Yuan, J.; Guan, X.; Peng, J. Advancements in Dermatological Applications of Curcumin: Clinical Efficacy and Mechanistic Insights in the Management of Skin Disorders. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzak-Drozd, K.; Niziński, P.; Hawrył, A.; Gancarz, M.; Hawrył, D.; Oliwa, W.; Pałka, M.; Markowska, J.; Oniszczuk, A. Potential of Curcumin in the Management of Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; McClements, D.J. Formulation of More Efficacious Curcumin Delivery Systems Using Colloid Science: Enhanced Solubility, Stability, and Bioavailability. Molecules 2020, 25, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, H.; Dey, P.S.; Das, D.; Bhattacharya, T.; Shah, M.; Mubin, S.; Maishu, S.P.; Akter, R.; Rahman, M.H.; Karthika, C.; et al. Curcumin Nanoparticles as Promising Therapeutic Agents for Drug Targets. Molecules 2021, 26, 4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madawi, E.A.; Al Jayoush, A.R.; Rawas-Qalaji, M.; Thu, H.E.; Khan, S.; Sohail, M.; Mahmood, A.; Hussain, Z. Polymeric Nanoparticles as Tunable Nanocarriers for Targeted Delivery of Drugs to Skin Tissues for Treatment of Topical Skin Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, T.G.; Gurnani, P.; Rho, J.Y. Characterisation of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 7738–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tsai, P.-C.; Ramezanli, T.; Michniak-Kohn, B.B. Polymeric nanoparticles-based topical delivery systems for the treatment of dermatological diseases. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 5, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, H.M.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I.; Ng, S.-F.; Katas, H.; Shah, S.U.; Khan, N.R. Formulation and Evaluation of Microwave-Modified Chitosan-Curcumin Nanoparticles—A Promising Nanomaterials Platform for Skin Tissue Regeneration Applications Following Burn Wounds. Polymers 2020, 12, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Tang, C.H.; Luo, F.C.; Yin, S.W.; Yang, X.Q. Topical application of zein-silk sericin nanoparticles loaded with curcumin for improved therapy of dermatitis. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 24, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhou, H.; Shu, J.; Fu, S.; Yang, Z. Skin wound healing promoted by novel curcumin-loaded micelle hydrogel. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, Q.; Li, Y.; Pang, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, P.; Fu, S. Curcumin nanoparticles incorporated in PVA/collagen composite films promote wound healing. Drug Deliv. 2020, 27, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.; Kim, M.; Won, H.; Jung, A.; Kim, J.; Koo, Y.; Lee, N.K.; Baek, S.-H.; Han, U.; Park, C.G.; et al. Secured delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor using human serum albumin-based protein nanoparticles for enhanced wound healing and regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzoghby, A.O.; Samy, W.M.; Elgindy, N.A. Albumin-based nanoparticles as potential controlled release drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2012, 157, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casa, D.M.; Scariot, D.B.; Khalil, N.M.; Nakamura, C.V.; Mainardes, R.M. Bovine serum albumin nanoparticles containing amphotericin B were effective in treating murine cutaneous leishmaniasis and reduced the drug toxicity. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 192, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo, L.E.A.; Brustolin Ludwig, D.; Tominaga, T.T.; Carletto, B.; Favero, G.M.; Mainardes, R.M.; Khalil, N.M. Bovine serum albumin nanoparticles improve the antitumour activity of curcumin in a murine melanoma model. J. Microencapsul. 2018, 35, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, C.; Auner, B.G. The use of polymers for dermal and transdermal delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004, 58, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.S.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; Nawaz, A.; Rashid, S.A.; Farid, A.; Mohaini, M.A.; Alsalman, A.J.; Hawaj, M.A.A.; Alhashem, Y.N. Formulation and Evaluation of Hydrophilic Polymer Based Methotrexate Patches: In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization. Polymers 2022, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niranjan, R.; Kaushik, M.; Prakash, J.; Venkataprasanna, K.S.; Arpana, C.; Balashanmugam, P.; Venkatasubbu, G.D. Enhanced wound healing by PVA/Chitosan/Curcumin patches: In vitro and in vivo study. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 182, 110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, R.; Hwang, S.; Park, T.; Chung, Y.J.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J.; Cheong, H.; Moon, C.; Min, K.A.; Shin, M.C. BSA/Silver Nanoparticle-Loaded Hydrogel Film for Local Photothermal Treatment of Skin Cancer. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajra, B.; Pandya, S.; Vidyasagar, G.; Rabari, H.; Dedania, R.; Rao, S. Poly vinyl alcohol Hydrogel and its Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, A.; Gupta, R.; Saraf, S.A. PLGA Nanoparticles of Anti Tubercular Drug: Drug Loading and Release Studies of a Water In-Soluble Drug. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2010, 2, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Khan, F.N.; Cosby, L.; Yang, G.; Winter, J.O. Polymer Concentration Maximizes Encapsulation Efficiency in Electrohydrodynamic Mixing Nanoprecipitation. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 719710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Xi, Y.; Qian, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J. Sustained release and enhanced bioavailability of injectable scutellarin-loaded bovine serum albumin nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 476, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahian Kalhor, N.; Saeidifar, M.; Ramshini, H.; Saboury, A.A. Interaction, cytotoxicity and sustained release assessment of a novel anti-tumor agent using bovine serum albumin nanocarrier. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 2546–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, R.P.; Singh, B.G.; Kunwar, A.; Priyadarsini, K.I. Interaction of a Model Hydrophobic Drug Dimethylcurcumin with Albumin Nanoparticles. Protein J. 2019, 38, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Guo, Y.; Ji, L.; Xue, H.; Li, X.; Tan, J. Insights into interactions between polyphenols and proteins and their applications: An updated overview. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, K.; Grauffel, C.; Lim, C. How Molecular Size Impacts RMSD Applications in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, Y.; Goto, M.; Masuda, T.; Takizawa, Y.; Suzuki, S. The Crystal Structure and the Fluorescent Properties of Curcumin. J. Jpn. Soc. Colour. Mater. 1999, 72, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Bounds, A.; Crumpton, M.; Long, M.; McDonough, H.; Srikhirisawan, I.; Gao, S. Potential Mechanisms of Lactate Dehydrogenase and Bovine Serum Albumin Proteins as Antioxidants: A Mixed Experimental–Computational Study. Biochem. Res. Int. 2025, 2025, 9638644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, L.; Kalampalika, E.; Yordanov, Y.; Petrov, P.D.; Tzankova, V.; Yoncheva, K. Formulation of Caffeine–Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Complex in Hydrogel for Skin Treatment. Gels 2025, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.M.; Paula, C.B.A.; Ribeiro, I.S.; Gomes, R.F.; Souza, J.M.T.; Marinho Filho, J.D.B.; Araújo, A.J.; Freire, R.S.; Sousa, J.S.; Costa Filho, R.N.; et al. Dextran-based nanoparticles for co-delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin in chemo-photodynamic cancer therapy. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayyullathil, F.; Chathoth, S.; Hago, A.; Patel, M.; Galadari, S. Rapid reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation induced by curcumin leads to caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis in L929 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Kinoshita, H.; Okamoto, T.; Sugiura, K.; Kawashima, S.; Kimura, T. Antioxidant Properties of Albumin and Diseases Related to Obstetrics and Gynecology. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safta, D.A.; Bogdan, C.; Iurian, S.; Moldovan, M.-L. Optimization of Film-Dressings Containing Herbal Extracts for Wound Care—A Quality by Design Approach. Gels 2025, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Gwon, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, W.; Jeon, Y.; Han, T.; Jeong, H.E.; Kim, J. Synergistic effects of gelatin and nanotopographical patterns on biomedical PCL patches for enhanced mechanical and adhesion properties. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 114, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, R.; Nazir, A.; Qadir, M.B.; Khaliq, Z.; Hareem, F.; Arshad, S.N.; Aslam, M. Fabrication and Physio-chemical characterization of biocompatible and antibacterial Vitis vinifera(grapes) loaded PVA nanomembranes for dermal applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, K.; Banthia, A.K.; Majumdar, D.K. Polyvinyl Alcohol—Gelatin Patches of Salicylic Acid: Preparation, Characterization and Drug Release Studies. J. Biomater. Appl. 2006, 21, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, F.; Yekrang, J.; Gholamshahbazi, N.; Ramyar, M.; Dehghanniri, P. Under-eye patch based on PVA-gelatin nanocomposite nanofiber as a potential skin care product for fast delivery of the coenzyme Q10 anti-aging agent: In vitro and in vivo studies. Emergent Mater. 2023, 6, 1903–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Dastmalchi, S.; Davaran, S. A simple improved desolvation method for the rapid preparation of albumin nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aniesrani Delfiya, D.S.; Thangavel, K.; Amirtham, D. Preparation of Curcumin Loaded Egg Albumin Nanoparticles Using Acetone and Optimization of Desolvation Process. Protein J. 2016, 35, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Coester, C.; Kreuter, J.; Langer, K. Desolvation process and surface characterisation of protein nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 194, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Santos, B.; Gremião, M.P.D.; Chorilli, M. A simple reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method for determination of in situ gelling curcumin-loaded liquid crystals in in vitro performance tests. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomathi, T.; Santhanalakshmi, K.; Monika, A.K.; John Joseph, J.; Khalid, M.; Shukri Albakri, G.; Kumar Yadav, K.; Shoba, K.; Durán-Lara, E.F.; Vijayakumar, S. Chitosan-lysine nanoparticles for sustained delivery of capecitabine: Formulation, characterization, and evaluation of anticancer and antifungal properties with molecular docking insights on anti-inflammatory potential. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 167, 112797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felemban, S.; Hamouda, A.F. Investigating Grape Seed Extract as a Natural Antibacterial Agent for Water Disinfection in Saudi Arabia: A Pilot Chemical, Phytochemical, Heavy-Metal, Mineral, and CB-Dock Study Employing Water and Urine Samples. Chemistry 2024, 6, 852–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Mozafari, M.R.; Ghaemi, S.; Ashengroph, M.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Mohammadabadi, M. Interaction of Epigallocatechin Gallate and Quercetin with Spike Glycoprotein (S-Glycoprotein) of SARS-CoV-2: In Silico Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, K.; Albeshr, M.F.; Shoba, K.; Lavanya, G.; Prasad, P.S.; Sudha, P.N. Evaluation of cytocompatibility and cell proliferation of electrospun chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/montmorillonite clay scaffold with l929 cell lines in skin regeneration activity and in silico molecular docking studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.H.P.; Botelho, E.B.; de Souza Gomes, T.J.; Kist, R.; Caceres, R.A.; Zanchi, F.B. Visual dynamics: A WEB application for molecular dynamics simulation using GROMACS. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, K.H.; Abdullah, A.; Kuswandi, B.; Hidayat, M.A. A novel high throughput method based on the DPPH dry reagent array for determination of antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 4102–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Khalil, M.I.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Gan, S.H. Advances in the analytical methods for determining the antioxidant properties of honey: A review. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 9, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subculture of Adherent Cell Lines. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/BG/en/technical-documents/protocol/cell-culture-and-cell-culture-analysis/mammalian-cell-culture/subculture-of-adherent (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Monton, C.; Sampaopan, Y.; Pichayakorn, W.; Panrat, K.; Suksaeree, J. Herbal transdermal patches made from optimized polyvinyl alcohol blended film: Herbal extraction process, film properties, and in vitro study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 69, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abahuni Ucar, M.; Gul, E.M.; Uygunoz, D.; Derun, E.M.; Piskin, M.B. Investigation of PVA Matrix Hydrogel Loaded with Centaurea cyanus Extract for Wound Dressing Applications: Morphology, Drug Release, Antibacterial Efficiency, and In Vitro Evaluation. Gels 2025, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanoparticles | Mean Size, nm | PDI | Zeta Potential, mV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty | 117 ± 5.5 | 0.286 | −27.5 |

| Loaded | 163 ± 6.5 | 0.234 | −28.5 |

| Vina Score | Cavity Volume (Å3) | Centre (x, y, z) | Docking Size (x, y, z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −8.8 | 4101 | 49, 22, 93 | 35, 26, 26 |

| −8.2 | 3494 | 20, 24, 101 | 26, 26, 35 |

| −8.1 | 8957 | 68, 22, 85 | 35, 35, 26 |

| −7.9 | 8389 | 0, 26, 108 | 35, 35, 26 |

| −6.6 | 18,855 | 47, 22, 119 | 35, 35, 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radeva, L.; Belchev, A.; Karimi Dardashti, P.; Yordanov, Y.; Spassova, I.; Kovacheva, D.; Spasova, M.; Petrov, P.D.; Tzankova, V.; Yoncheva, K. Formulation of PVA Hydrogel Patch as a Drug Delivery System of Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin. Gels 2025, 11, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120979

Radeva L, Belchev A, Karimi Dardashti P, Yordanov Y, Spassova I, Kovacheva D, Spasova M, Petrov PD, Tzankova V, Yoncheva K. Formulation of PVA Hydrogel Patch as a Drug Delivery System of Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin. Gels. 2025; 11(12):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120979

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadeva, Lyubomira, Aleksandar Belchev, Parsa Karimi Dardashti, Yordan Yordanov, Ivanka Spassova, Daniela Kovacheva, Mariya Spasova, Petar D. Petrov, Virginia Tzankova, and Krassimira Yoncheva. 2025. "Formulation of PVA Hydrogel Patch as a Drug Delivery System of Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin" Gels 11, no. 12: 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120979

APA StyleRadeva, L., Belchev, A., Karimi Dardashti, P., Yordanov, Y., Spassova, I., Kovacheva, D., Spasova, M., Petrov, P. D., Tzankova, V., & Yoncheva, K. (2025). Formulation of PVA Hydrogel Patch as a Drug Delivery System of Albumin Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin. Gels, 11(12), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120979