Malignant Transformation in Diabetic Foot Ulcers—Case Reports and Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

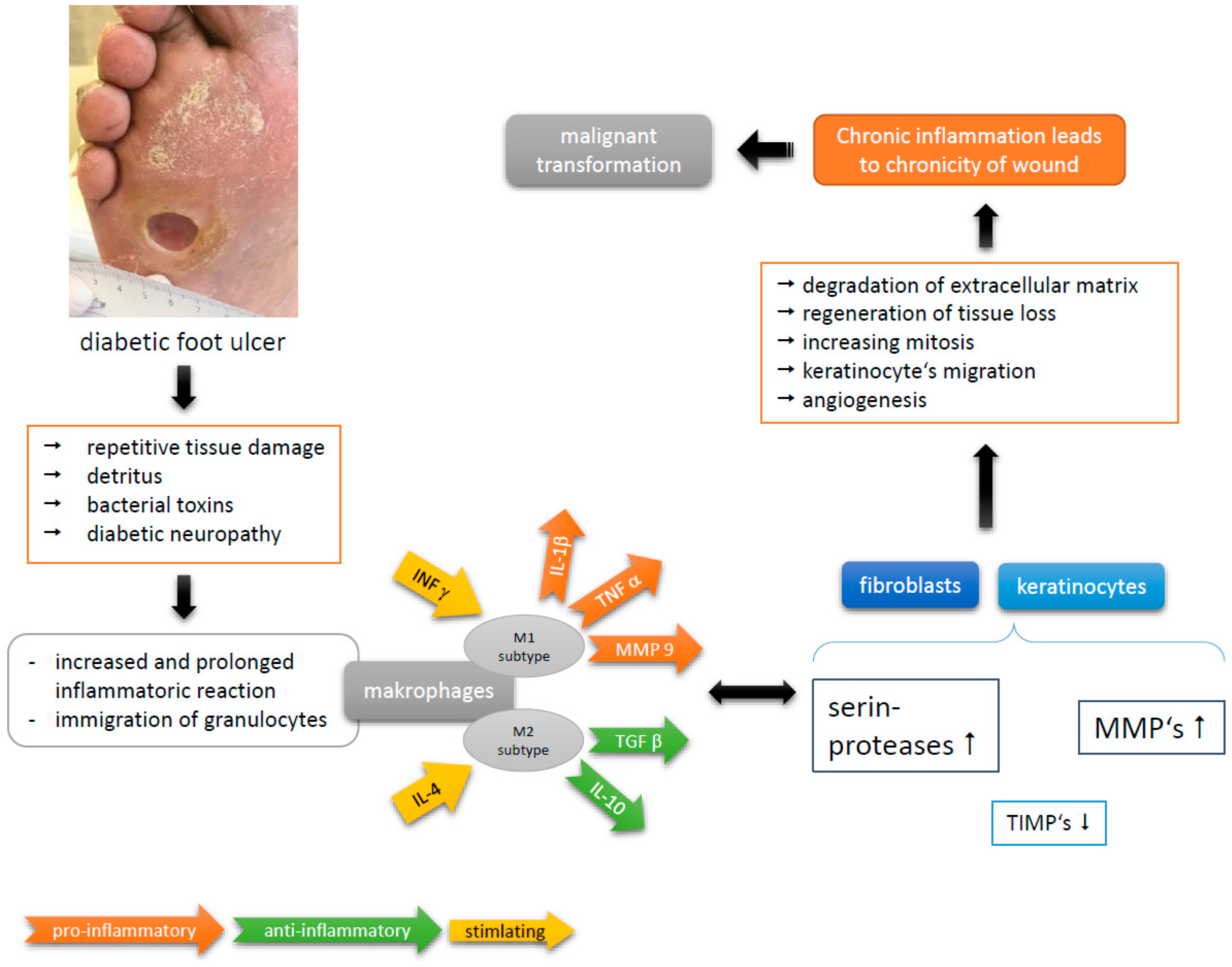

1.1. Pathophysiology in Chronic Wounds

1.2. History of Marjolin’s Ulcer

1.3. Attributes of Marjolin’s Ulcer

- -

- nodule or verrucous formation;

- -

- induration;

- -

- everted margins;

- -

- excessive granulation tissue;

- -

- increase in extent during time;

- -

- contact bleeding;

- -

- absent tendency of healing within 3 months or more.

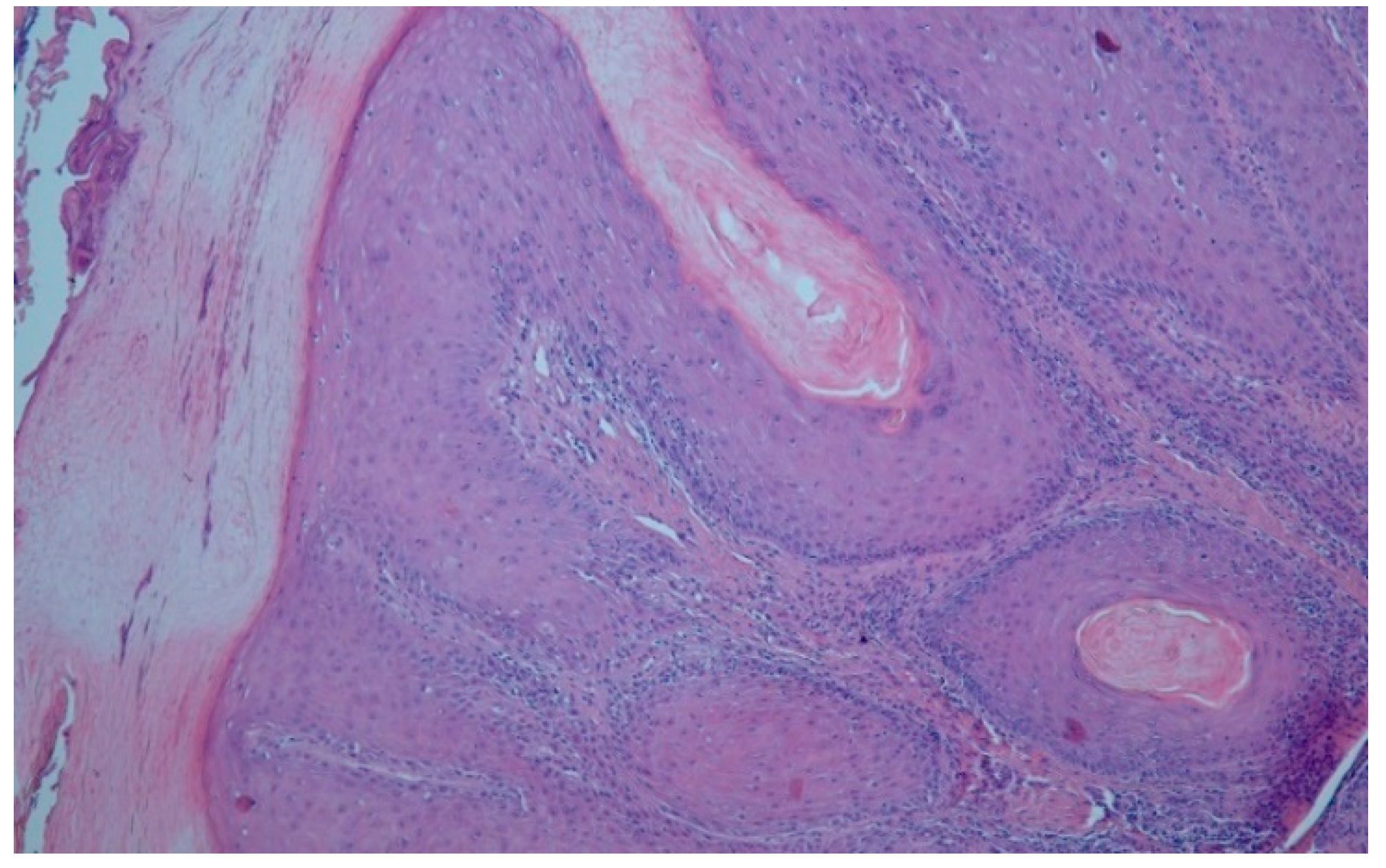

1.4. Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Chronic Ulcers

1.5. Diagnostic in MU

1.6. Treatment Options in MU

2. Patient’s Characteristics

2.1. Case 1

2.2. Case 2

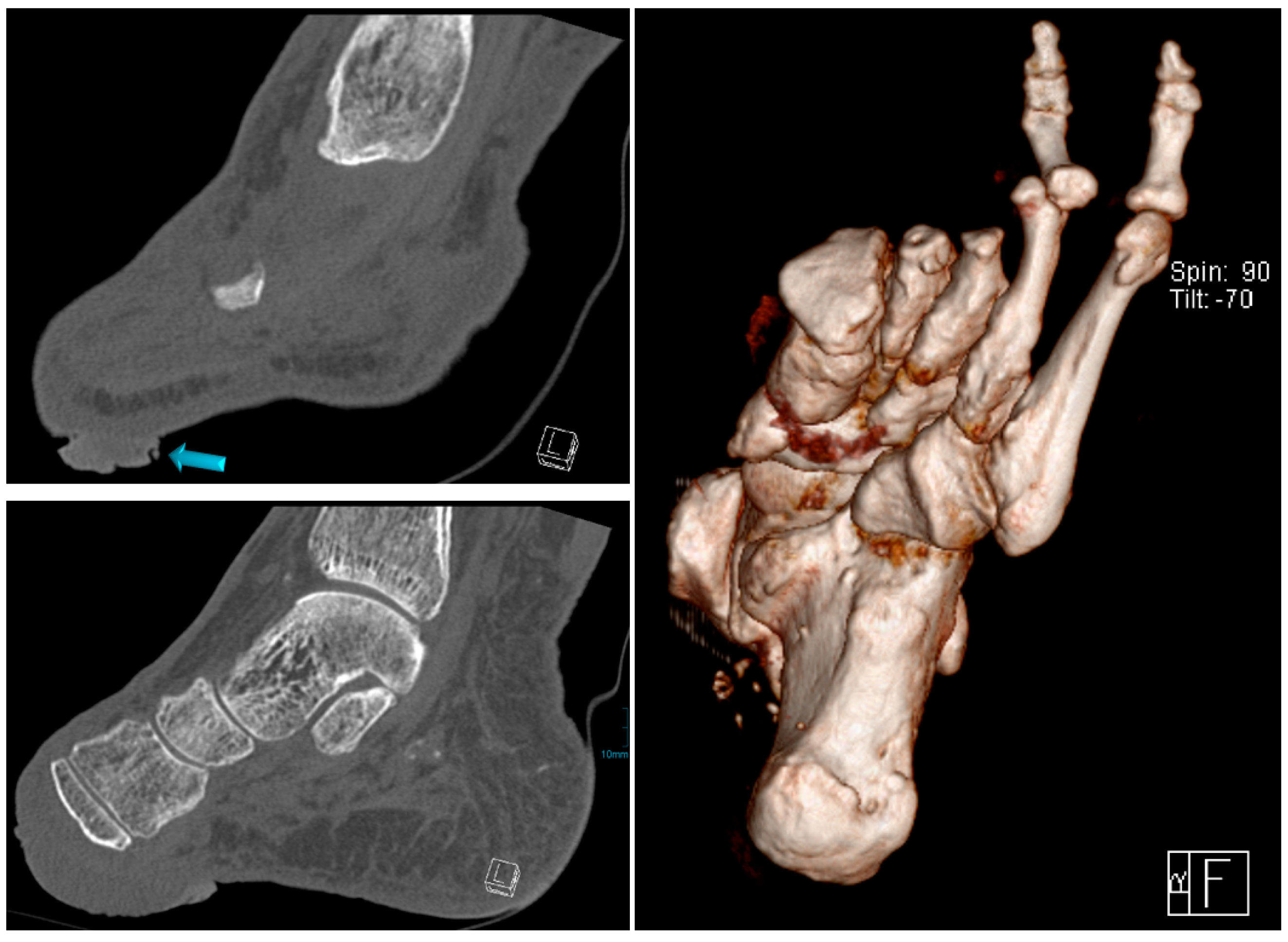

3. Clinical Findings and Treatment

3.1. Case 1

3.2. Case 2

4. Outcome and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHD | coronary heart disease |

| DFU | diabetic foot ulcer |

| EGF | epithelial growth factor |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| IL | interleukin |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| MR-imagine/MRI | Magnet-resonance imaging, MRT |

| MU | Marjolin’s ulcer |

| PAD | peripheral arterial disease |

| PDGF | platelet derived growth factor |

| SCC | squamous cell cancer |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| TIMP | inhibitors of MMP |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| BCC | basal cell carcinoma |

References

- Liu, Y.; Min, D.; Bolt, T.; Nubé, V.; Twigg, S.M.; Yue, D.K.; McLennan, S.V. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 predicts poor wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loots, M.; Lamme, E.; Zeegelaar, J.; Mekkes, J.R.; Bos, J.D.; Middelkoop, E. Differences in cellular infiltrate and extracellular Matrix of chronic diabetic and venous ulcers versus acute wounds. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwomeh, B.C.; Yager, D.R.; Cohen, I.K. Physiology of the chronic wound. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1998, 25, 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lobmann, R. Das Diabetische Fußsyndrom; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mast, B.A.; Schultz, G.S. Interactions of cytokines, growth factors and proteases in acute and chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 1996, 4, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yager, D.R.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.X.; Diegelmann, R.F.; Cohen, I.K. Wound fluids from human pressure ulcers contain elevated matrix metalloproteinase levels and activity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1996, 107, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, G.M.; Quah, S.; Sampath, P. Cancer: The dark side of wound healing. Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc. J. 2018, 285, 4516–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonio, N.; Bønnelyke-Behrndtz, M.L.; Ward, L.C. The wound inflammatory response exacerbates growth of pre-neoplastic cells and progression to cancer. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2219–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: Back ti Virchow. Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinau, D.; Surber, C.; Jlick, S.S.; Meier, C.R. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of skin cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, N.; Pack, G.T. The development of cancer in burn scars: An analysis and report of thirty-four cases. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1930, 58, 749–751. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick, J., III; Pendergast, W.J., Jr.; Vasconez, L.O. Marjolin′s ulcer: An immunologically priviledged tumor? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1976, 57, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazalínski, D.; Pryzbek-Mita, J.; Baranska, B.; Wiech, P. Marjolin′s ulcer in chronic wounds—Review of available literature. Contemp. Oncol. 2017, 21, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Novick, M.; Gard, D.A.; Hardy, S.B. Burn scar carcinoma: A review and analysis of 46 cases. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1977, 17, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjolin, J. Dictionnaire de Médecine; Adelon, N., Ed.; Hachette Livre–BNF: Paris, Fance, 1828; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, C. On warty tumours in cicatrices. Lond. Med. Gaz. 1833, 13, 481–482. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuytren, B. Lecons Orales de Clinique Chirurgical Faites a L′hôtel-Dieu de Paris; Chez Germer Baillère: Paris, France, 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.W. Observations upon the warty ulcer of Marjolin. Dublin Quart. J. Med. Sci. 1850, 9, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalière, R.; Mercado, D. Squamous cell carcinoma from Marjolin′s ulcer of the foot in diabetic patient: Case study. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018, 57, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J.T.; Kirsner, R.S. Wounds and malignancy. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2003, 16, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielczyk, B.; Murawa, D.; Nowaczyk, P. Marjolin′s ulcer as a result of chronic venous ulcers and chronic skin injury—Case studies. Pol. Przeglad Chir. 2007, 79, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Chalya, F.L.; Mabula, J.B.; Rambau, P. Marjolin′s ulcers at a university teaching hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: A retrospektive review of 56 cases. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal-Vern, A.; Criswell, B.K. Burn scar neoplasm: A literature review and statistical analysis. Burns 2005, 31, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, T.; Upton, J.; Marcellino, V.; Tun, C.J.; Rossier, A.B.; Hachend, H.J. Carcinoma in chronic pressure sores: A fulminant disease process. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1986, 77, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankard, C.E.; Cruse, C.W.; Wells, K.E.; Karl, R. Chronic pressure ulcer carcinomas. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1993, 30, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekarek, B.; Buck, S.; Osher, L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin′s ulcers: Diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Coll. Certif. Wound Spec. 2011, 3, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, B.; Pitcher, J.D., Jr.; Adams, S.C.; Temple, H.T. Squamous cell carcinoma of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2009, 30, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, C.; Sanger, J. Marjolin′s ulcer: A case series and literature review. Wounds 2014, 26, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Poccia, I.; Persichetti, P.; Marangi, G.F.; Gigliofiorito, P.; Campa, S.; DelBuono, R.; Lamberti, D. Basal cell caricinoma arising in a chronic venous ulcer: Two cases and a review of the literature. Wounds 2014, 26, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Senet, P.; Combemale, P.; Debure, C.; Baudot, N.; Machet, L.; Aout, M.; Lok, C. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: The value of systematic wound biopsies: A prospective multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch. Dermatol. 2012, 148, 704–708. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, A.A.; Schnyder, U.W. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma within the clinical picture of a chronic venous insufficiency in the fird stage. Dermatologica 1990, 181, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.M.; Sinha, Y.; Jaffe, W. Marjolin′s ulcers: A rare entity with a call for early diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014208176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solus, J.; Murphy, G.; Kraft, S. Cutaneous suqamous cell carcinoma of the lower extremities show distinct clinical and pathological features. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 24, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr-Valentic, M.; Sammi, K.; Rohlen, B. Marjolin′s ulcer: Modern analysis of an ancient problem. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 123, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, I. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of foot: Case report. Oman Med. J. 2009, 24, 49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, M.; Kapi, E.; Kuvat, S.V.; Ozekinci, S. Current concepts in the management of Marjolin′s ulcer: Outcomes from a standardized treatment protocol in 16 cases. J. Burn Care Res. 2010, 31, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgado, R.; Ward, S.; Suryaprasad, S.G. Squamous cell carcinoma of the hallux. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. 2000, 90, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Giannone, A.L.; Mehrabi, E.; Khan, A.; Giannone, R.E. Management of Marjolin′s ulcer in a chronic pressure sore secondary to paraplegia: A radical surgical solution. Int. Wound J. 2011, 8, 533–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, W.T. Clinical management of nonhealing wounds. In Wound healing: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 541–561. [Google Scholar]

- Berkwits, L.; Yarkony, G.M.; Lewis, V. Marjolin′s Ulcer complicating a pressure ulcer: Case report and Literature Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1986, 67, 831–836. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, T.; Lewandowska, M. Marjolin′s ulcer—Malignancy developing in chronic ulcer and scars. Analysis of 8 cases. Przeglad Dermatol. 2010, 97, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marín, J.A.; Martinez-Gomez, D.; Campillo-Soto, A.; Aguayo-Albasini, J.L. Marjolin′s ulcer. A 10 year experience in a diabetic foot unit. Cirugía y Cirujanos 2016, 84, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, J.W.; Li, B.D.; Gonzalez, E.; Valiulis, J.P.; Cunningham, M.; McCulloch, J. Diagnostic dilemma: Nonhealing ulcer in a diabetic foot. Wounds 2004, 16, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mirshams, M.; Razzaghi, M.; Noormohammadpour, P.; Kamyab, K.; Sabouri Rad, S. Incidence of incomplete excision in surgical treated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and identification of the related risk factors. Acta Med. Iran. 2011, 49, 806–809. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao, H.Y.; Chang, S.C.; Wang, C.H.; Tzeng, Y.S.; Chen, S.G. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 104, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, R.; Wruhs, M.; Peinhaupt, T.; Stella, A.; Breier, F.; Steiner, A. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the right thenar region with bone involvement and lymph node metastases. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2017, 9, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Meaning |

|---|---|

| T1 | Tumor extent ≤2 cm |

| T2 | Tumor extent >2 cm and <5 cm |

| T3 | Tumor extent ≥5 cm |

| T4 | Tumor affects deeper structures such as bone, cartilage or muscle |

| N0 | Not any lymph node metastases. |

| N1 | Local lymph node metastases |

| M0 | Not any metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dörr, S.; Lucke-Paulig, L.; Vollmer, C.; Lobmann, R. Malignant Transformation in Diabetic Foot Ulcers—Case Reports and Review of the Literature. Geriatrics 2019, 4, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4040062

Dörr S, Lucke-Paulig L, Vollmer C, Lobmann R. Malignant Transformation in Diabetic Foot Ulcers—Case Reports and Review of the Literature. Geriatrics. 2019; 4(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleDörr, Stefan, Lara Lucke-Paulig, Christian Vollmer, and Ralf Lobmann. 2019. "Malignant Transformation in Diabetic Foot Ulcers—Case Reports and Review of the Literature" Geriatrics 4, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4040062