Visualization Concept of Automotive Quality Management System Standard

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Visualization Management

1.2. Management Systems Standards Suitable for Clustering

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Automotive Quality Standards

- To develop a consensus regarding international fundamental quality system requirements, primarily for the participating companies’ direct suppliers of production materials, products, or service parts or finishing services (e.g., heat treating, painting, and plating). These requirements will also be available for other interested parties in the automotive industry;

- To develop policies and procedures for the common IATF third party registration scheme to ensure consistency worldwide;

- To provide appropriate training to support IATF 16949 requirements and the IATF registration scheme;

- To establish formal liaisons with appropriate organizations to support the goals of IATF [17].

2.2. Methodology of Visualization

- Selection of a data set, which can also be completed by importing data from an external database, their correct filtering and data transformation, which is performed if we do not have the data in the required form and it is necessary to transform it;

- Defining individual nodes or cells of the cluster and graphical differentiation according to selected criteria, whether using the size, shape, color, or other attribute of the node;

- Defining individual edges between the nodes and, again, graphical differentiation in terms of thickness, format, color, etc.;

- Control of the interaction correctness;

- Research and further study of the cluster.

3. Results

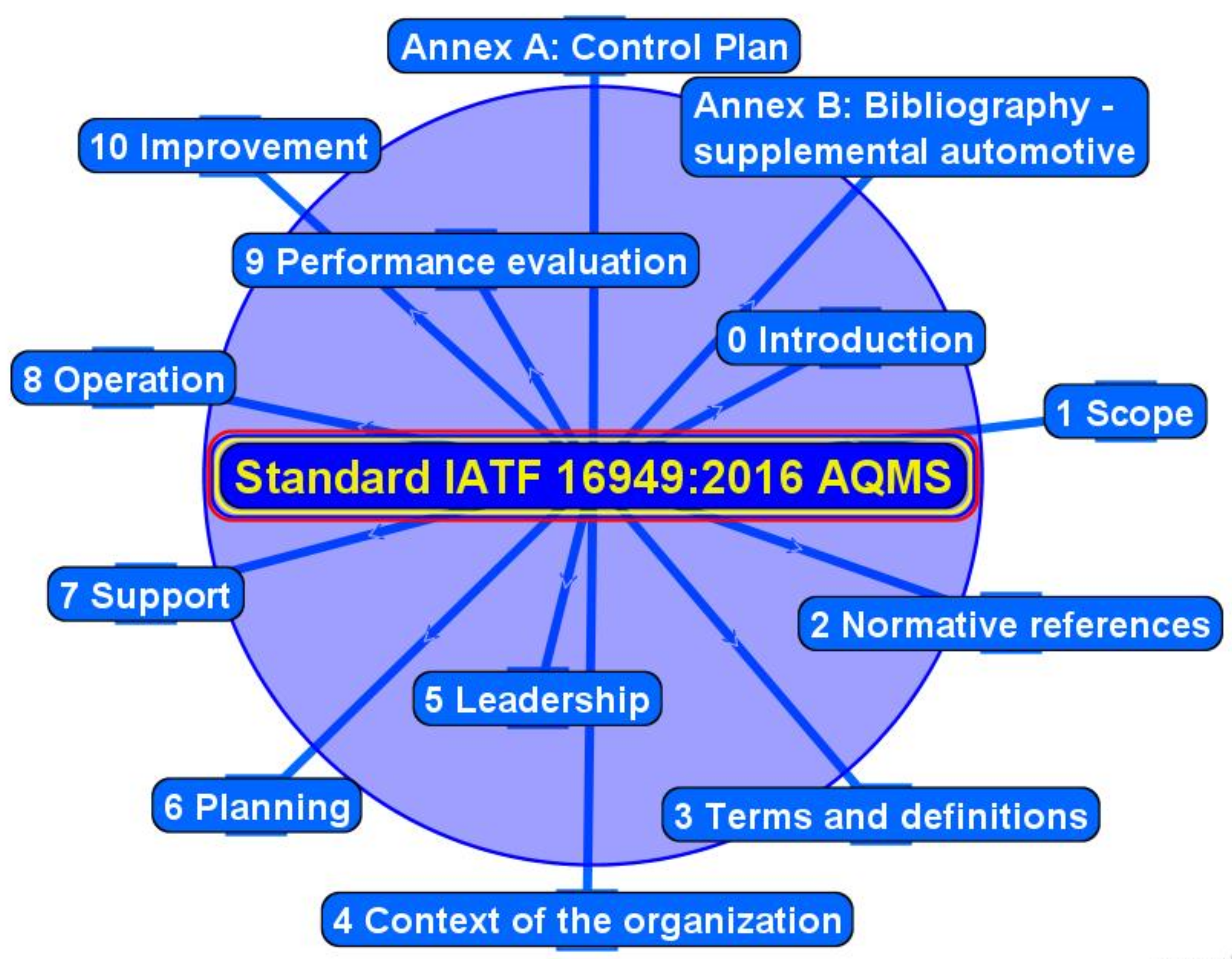

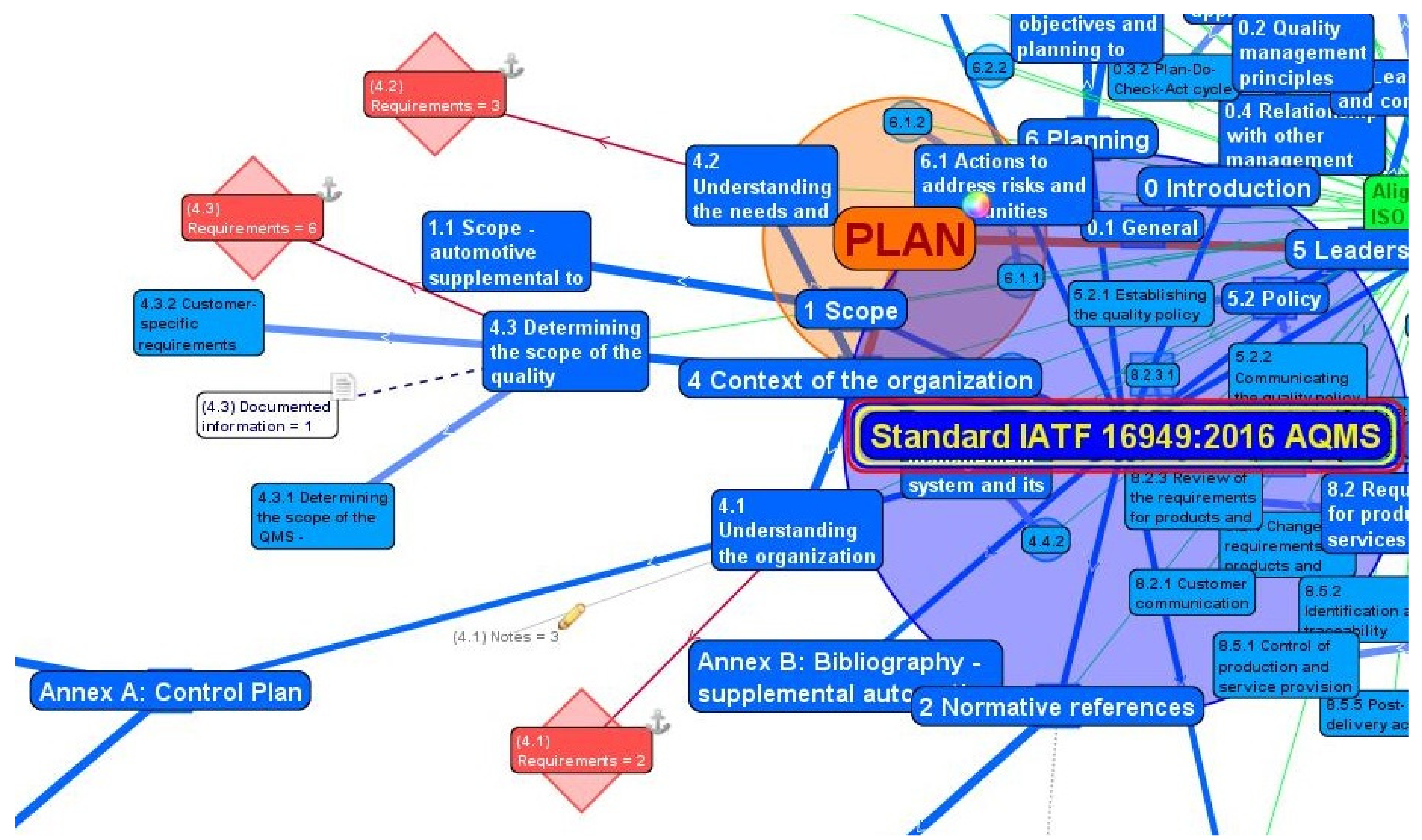

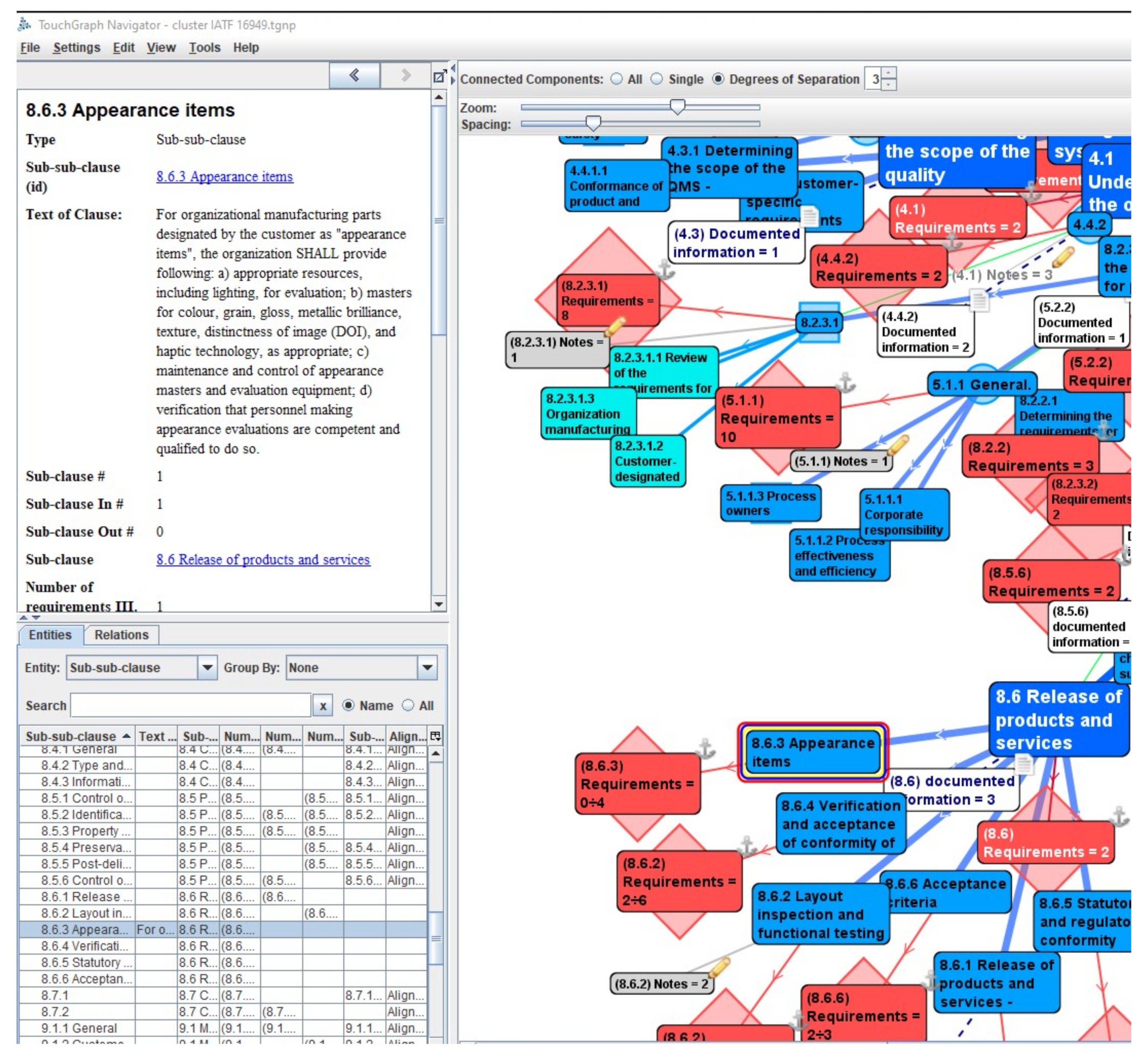

3.1. Development of the Visualized Cluster of IATF 16949 Standard

3.2. Management Review and Audits Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Unwin, A. Why is Data Visualization Important? What is Important in Data Visualization? Harvard Data Science Review. 31 January 2020; 7p. Available online: https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/zok97i7p (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Sosulski, K. Data Visualization Made Simple: Insights Into Becoming Visual, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2019; 285p, ISBN 978-1-138-50387-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, B. Visualizing Data: Exploring and Explaining Data with the Processing Environment, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2008; 384p, ISBN -13:978-0596514556. [Google Scholar]

- Moen, R.; Norman, D.; Clifford, L. Circling Back; Associates in Process Improvement; Quality Progress: Georgetown, TX, USA, 2010; Volume 43, pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Komenský, J.A. Veľká Didaktika (The Great Didactic), 2nd ed.; Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladateľstvo: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1991; 271p, ISBN 8008010223. [Google Scholar]

- Krum, R. Cool Infographics: Effective Communication with Data Visualization and Design, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2013; 370p, ISBN 978-1-118-58230-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani, S. Visual Design Thinking: A Collaborative Dimensions framework to profile visualizations. Des. Stud. 2019, 63, 92–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, L. What is visualization? Vis. Stud. 2011, 26, 36–49. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1472586X.2011.548488 (accessed on 10 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Pauliková, A.; Lestyánszka Škůrková, K.; Kopilčáková, L.; Zhelyazkova-Stoyanova, A.; Kirechev, D. Innovative Approaches to Model Visualization for Integrated Management Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvelihárová, D.; Pauliková, A. Water efficiency management systems for transport drinking water supply. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference Advances in Environmental Engineering, Online, 25–26 November 2021; VŠB-Technical University of Ostrava: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2021. ISSN: 1755-1307. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/900/1/012005/pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- What is an IWA? In ISO Focus—The Magazine of the International Organization for Standardization; ISO’s Central Secretariat: Genève, Switzerland, November 2007; Volume 4, p. 28. ISSN 1729-8709. Available online: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/news/magazine/ISO%20Focus%20(2004-2009)/2007/ISO%20Focus,%20November%202007.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Consolidated ISO Supplement—Procedures for the Technical Work—Procedures Specific to ISO. ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1, 12th ed.; International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2021; p. 14. Available online: https://isotc.iso.org/livelink/livelink/fetch/-10469877/10469901/16474137/Annex_SL_%2D_excerpt_from_ISO_IEC_Directives_Part_1_and_Consolidated_ISO_Supplement_%2D_2021_%2812th_edition%29.pdf?nodeid=17859835&vernum=-2 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Management System Standards List. 14 December 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/management-system-standards-list.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Lambert, G. A stroll down Quality Street. In ISO Focus #123. Your Gateway to International Standards; International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 36–43. ISSN 2226-1095. Available online: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/news/magazine/ISOfocus%20(2013-NOW)/en/2017/ISOfocus_123/ISOfocus_123_EN.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Technical Specification IATF 16949:2016 Automotive Quality Management System Standard, Quality Management System Requirements for Automotive Production and Relevant Service Parts Organizations, 1st ed.; International Automotive Task Force (IATF), SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2016; p. 119. ISBN 9781605343471.

- BSI—British Standard Institution. What is IATF 16949:2016 Automotive Quality Management? Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-US/iatf-16949-automotive (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- About IATF. International Automotive Task Force (IATF). SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK,, 2017. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/about-iatf/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Hoyle, D. Automotive Quality System Handbook, 2nd ed.; ISO/TS 16949:2002 Edition; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 712, eBook; ISBN 9780080458502. [Google Scholar]

- Areas of Impact for Client Consideration Taken from the Rules for Achieving and Maintaining IATF Recognition 5th Edition for Technical Specification IATF 16949, 1st ed; 2016 Automotive Quality Management System Standard, Quality management system requirements for automotive production and relevant service parts organizations; International Automotive Task Force (IATF), SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017; p. 19. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Rules-5th-Edition-Areas-of-Impact-for-Client-Condisderation-01Feb2017.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Rules for Achieving and Maintaining IATF Recognition 5th Edition (Frequently Asked Questions) for Technical Specification IATF 16949, 5th ed; 2016 Automotive Quality Management System Standard, Quality Management System Requirements for Automotive Production and Relevant Service Parts Organizations; International Automotive Task Force (IATF), SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2021; p. 8. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IATF-Rules-5th-Edition_FAQs-February-2021.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Standard ISO 9001:2015 Quality Management Systems—Requirements; ISO/TC 176/SC 2 Quality Systems, ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems and ICS: 03.120.10 Quality Management and Quality Assurance, 5th ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 29.

- Standard ISO 9000:2015 Quality Management Systems—Fundamentals and Vocabulary, ISO/TC 176/SC 1 Concepts and Terminology. ICS: 01.040.03 Services. Company Organization, Management and Quality. Administration. Transport. Sociology. (Vocabularies) and ICS: 03.120.10 Quality Management and Quality Assurance, 4th ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 51.

- Laskurain-Iturbe, I.; Arana-Landín, G.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O. How does IATF 16949 add value to ISO 9001? An empirical study. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 32, 1341–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Automotive Task Force. IATF 16949:2016—Sanctioned Interpretations, 5th ed.; Sanctioned Interpretation (SIs) of Technical Specification IATF 16949:2016 Automotive Quality Management System Standard, Quality Management System Requirements for Automotive Production and Relevant Service Parts Organizations; International Automotive Task Force (IATF), SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2022; p. 30. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IATF-Rules-5th-Edition-Sanctioned-Interpretations_Apr-2022.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- TouchGraph Navigator. Available online: https://www.touchgraph.com/navigator (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Majernik, M.; Daneshjo, N.; Chovancová, J.; Sanciova, G. Design of integrated management systems according to the revised ISO standards. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATF Observer Guideline, 1st ed; International Automotive Task Force (IATF), SMMT Industry Forum Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017; p. 2. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IATF-Observer-Guideline.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Standard ISO 10012:2003 Measurement Management Systems—Requirements for Measurement Processes and Measuring Equipment, ISO/TC 176/SC 3 Supporting Technologies. ICS: 01.040.03 Services. Company Organization, Management and Quality. Admin-istration. Transport. Sociology. (Vocabularies) and 03.100.70 Management systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; p. 19.

- Standard ISO 14001:2015 Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use, ISO/TC 207/SC 1 Environmental Management Systems. ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems and ICS 13.020.10 Environmental Management, 3rd ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 35.

- Standard ISO/IEC 27001:2013 Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements, ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 27 Information Security. Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection; ICS 35.030 IT Security and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 23.

- Standard ISO 22301:2019 Security and Resilience—Business Continuity Management Systems—Requirements, ISO/TC 292 Security and Resilience. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 21.

- Standard ISO 28000:2007 Specification for Security Management Systems for the Supply Chain, ISO/TC 292 Security and Resilience. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; p. 16.

- Standard ISO 28001:2007 Security Management Systems for the Supply Chain—Best Practices for Implementing Supply Chain Security, Assessments and Plans—Requirements and Guidance, ISO/TC 292 Security and Resilience. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; p. 27.

- Standard ISO 28002:2011 Security Management Systems for the Supply Chain—Development of Resilience in the Supply Chain—Requirements with Guidance for Use, ISO/TC 292 Security and Resilience; ICS: 03; 100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 55.

- Standard ISO 30301:2019 Information and Documentation—Management Systems for Records—Requirements, ISO/TC 46/SC 11 Archives/Records Management. ICS: 01.140.20 Information Sciences, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 16.

- Standard ISO 37301:2021 Compliance Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use, ISO/TC 309 Governance of Organizations. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.02 Governance and Ethics and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 40.

- Standard ISO 39001:2012 Road Traffic Safety (RTS) Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use, ISO/TC 241 Road traffic Safety Management Systems. ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems and ICS: 03.220.20 Road Transport, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; p. 37.

- Standard ISO 44001:2017 Collaborative Business Relationship Management Systems—Requirements and Framework, ISO/TC 286 Collaborative Business Relationship Management. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.70 Management SYSTEMS, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 60.

- Standard ISO 50001:2018; Energy Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use, ISO/TC 301 Energy Management and Energy Savings. ICS: 27.015 Energy Efficiency. Energy Conservation in General and ICS:03.100.70 Management Systems, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 30.

- Standard ISO/AWI 56001 Innovation Management—Innovation Management System—Requirements, ISO/TC 279 Innovation Management. ICS: 03.100.01 Company Organization and Management in General and ICS: 03.100.40 Research and Development and ICS: 03.100.70 Management Systems, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization with Technical Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, Under development.

- Naden, C. A New Evolution for Quality Management in the Automotive Industry; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.iso.org/news/2016/08/Ref2109.html (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Silva, C.S.; Magano, J.; Matos, A.; Nogueira, T. Sustainable Quality Management Systems in the Current Paradigm: The Role of Leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, R.; Šujanová, J.; Ševčíková, M. The importance of quality inspection in the process of permanent improvement. In Toyotaryzm. Analiza Strumieni Wartości z Wykorzystaniem Metody Bost, 1st ed.; Polski Instytut Jakości: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 33–61. ISBN 978-83-946495-3-1. [Google Scholar]

| Phase of PDCA Cycle | ISO 9001 (Base) and IATF 16949 (Extension/Supplemental) |

|---|---|

| 0 Introduction | |

| 0.1 General | |

| 0.2 Quality management principles | |

| 0.3 Process approach | |

| 0.3.1 General | |

| 0.3.2 Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle | |

| 0.3.3 Risk-based thinking | |

| 0.4 Relationship with other MSSs 1 | |

| 1 Scope | |

| 1.1 Scope—automotive supplemental to ISO 9001:2015 | |

| 2 Normative references | |

| 2.1 Normative and informative references | |

| 3 Terms and definitions | |

| 3.1 Terms and definitions for the automotive industry | |

| 4 Context of the organization | |

| 4.1 Understanding the organization and its context | |

| I. phase: PLAN | 4.2 Understanding the needs and expectations of interested parties |

| I. phase: PLAN | 4.3 Determining the scope of the QMS 2 |

| 4.3.1 Determining the scope of the QMS—supplemental | |

| 4.3.2 Customer-specific requirements | |

| 4.4 Quality management system and its processes | |

| 4.4.1 | |

| I. phase: PLAN | 4.4.1.1 Conformance of product and processes |

| I. phase: PLAN | 4.4.1. 2 Product safety |

| 4.4.2 | |

| 5 Leadership | |

| 5.1 Leadership and commitment | |

| 5.1.1 General | |

| 5.1.1.1 Corporate responsibility | |

| 5.1.1.2 Process effectiveness and efficiency | |

| 5.1.1.3 Process owners | |

| 5.1.2 Customer focus | |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.2 Policy |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.2.1 Establishing the quality policy |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.2.2 Communicating the quality policy |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.3 Organizational roles, responsibilities, and authorities |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.3.1 Organizational roles, responsibilities, and authorities—supplemental |

| I. phase: PLAN | 5.3.2 Responsibility and authority for product requirements and corrective actions |

| All clauses No. 6—I. phase: PLAN | 6 Planning |

| 6.1 Actions to address risks and opportunities | |

| 6.1.1 | |

| 6.1.2 | |

| 6.1.2.1 Risk analysis | |

| 6.1.2.2 Preventive action | |

| 6.1.2.3 Contingency plans | |

| 6.2 Quality objectives and planning to achieve them | |

| 6.2.1 | |

| 6.2.2 | |

| 6.2.2 | |

| 6.2.2.1 Quality objectives and planning to achieve them—supplemental | |

| 6.3 Planning of changes | |

| All clauses No. 7—II. phase: DO | 7 Support |

| 7.1 Resources | |

| 7.1.1 General | |

| 7.1.2 People | |

| 7.1.3 Infrastructure | |

| 7.1.3.1 Plan, facility, and equipment planning | |

| 7.1.4 Environment for the operation of processes | |

| 7.1.4.1 Environment for the operation of processes—supplemental | |

| 7.1.5 Monitoring and measuring resources | |

| 7.1.5.1 General | |

| 7.1.5.1.1 Measurement system analysis | |

| 7.1.5.2 Measurement traceability | |

| 7.1.5.2.1 Calibration/verification records | |

| 7.1.5.3 Laboratory requirements | |

| 7.1.5.3.1 Internal laboratory | |

| 7.1.5.3.2 External laboratory | |

| 7.1.6 Organizational knowledge | |

| 7.2 Competence | |

| 7.2.1 Competence—supplemental | |

| 7.2.2 Competence—on-the-job | |

| 7.2.3 Internal auditor competency | |

| 7.2.4 Second-party auditor competency | |

| 7.3 Awareness | |

| 7.3.1 Awareness—supplemental | |

| 7.3.2 Employee motivation and empowerment | |

| 7.4 Communication | |

| 7.5 Documented information | |

| 7.5.1 General | |

| 7.5.1.1 Quality management system documentation | |

| 7.5.2 Creating and updating | |

| 7.5.3 Control of documented information | |

| 7.5.3.1 | |

| 7.5.3.2 | |

| 7.5.3.2.1 Record retention | |

| 7.5.3.2.2 Engineering specifications | |

| All clauses No. 8—II. phase: DO | 8 Operation |

| 8.1 Operational planning and control | |

| 8.1.1 Operational planning and control—supplement | |

| 8.1.2 Confidentiality | |

| 8.2 Requirements for products and services | |

| 8.2.1 Customer communication | |

| 8.2.1.1 Customer communication—supplemental | |

| 8.2.2 Determining the requirements for products and services | |

| 8.2.2.1 Determining the requirements for products and services—supplemental | |

| 8.2.3 Review of the requirements for products and services | |

| 8.2.3.1 | |

| 8.2.3.1.1 Review of the requirements for products and services—supplemental | |

| 8.2.3.1.2 Customer-designated special characteristics | |

| 8.2.3.1.3 Organization manufacturing feasibility | |

| 8.2.3 Review of the requirements for products and services | |

| 8.2.4 Changes to requirements for products and services | |

| 8.3 Design and development of products and services | |

| 8.3.1 General | |

| 8.3.1.1 Design and development of products and services—supplemental | |

| 8.3.2 Design and development planning | |

| 8.3.2.1 Design and development planning—supplemental | |

| 8.3.2.2 Product design skills | |

| 8.3.2.3 Development of products with embedded software | |

| 8.3.3 Design and development inputs | |

| 8.3.3.1 Product design and development inputs | |

| 8.3.3.2 Manufacturing process design input | |

| 8.3.3.3 Special characteristics | |

| 8.3.4 Design and development controls | |

| 8.3.4.1 Monitoring | |

| 8.3.4.2 Design and development of validation | |

| 8.3.4.3 Prototype program | |

| 8.3.4.4 Product approval process | |

| 8.3.5 Design and development outputs | |

| 8.3.5.1 Design and development outputs—supplemental | |

| 8.3.5.2 Manufacturing process design output | |

| 8.3.6 Design and development changes | |

| 8.3.6.1 Design and development changes—supplemental | |

| 8.4 Control of externally provided processes, products and services | |

| 8.4.1 General | |

| 8.4.1.1 General—supplemental | |

| 8.4.1.2 Supplier selection process | |

| 8.4.1.3 Customer-directed sources (also known as “Directed-Buy”) | |

| 8.4.2 Type and extent of control | |

| 8.4.2.1 Type and extent of control—supplemental | |

| 8.4.2.2 Statutory and regulatory requirements | |

| 8.4.2.3 Supplier quality MS development | |

| 8.4.2.3.1 Automotive product-related SW or automotive products with embedded SW | |

| 8.4.2.4 Supplier monitoring | |

| 8.4.2.4.1 Second-party audits | |

| 8.4.2.5 Supplier development | |

| 8.4.3 Information for external providers | |

| 8.4.3.1 Information for external providers—supplemental | |

| 8.5 Production and service provision | |

| 8.5.1 Control of production and service provision | |

| 8.5.1.1 Control plan | |

| 8.5.1.2 Standardized work—operator instructions and visual standards | |

| 8.5.1.3 Verification of job set-ups | |

| 8.5.1.4 Verification after shutdown | |

| 8.5.1.5 Total productive maintenance | |

| 8.5.1.6 Management of production tooling and manufacturing, test, inspection tooling and equipment | |

| 8.5.1.7 Production scheduling | |

| 8.5.2 Identification and traceability | |

| 8.5.2.1 Identification and traceability—supplemental | |

| 8.5.3 Property belonging to customers or external providers | |

| 8.5.4 Preservation | |

| 8.5.4.1 Preservation—supplemental | |

| 8.5.5 Post-delivery activities | |

| 8.5.5.1 Feedback of information from service | |

| 8.5.5.2 Service agreement with customer | |

| 8.5.6 Control of changes | |

| 8.5.6.1 Control of changes—supplemental | |

| 8.5.6.1.1 Temporary change of process controls | |

| 8.6 Release of products and services | |

| 8.6.1 Release of products and services—supplemental | |

| 8.6.2 Layout inspection and functional testing | |

| 8.6.3 Appearance items | |

| 8.6.4 Verification and acceptance of conformity of externally provided products and services | |

| 8.6.5 Statutory and regulatory conformity | |

| 8.6.6 Acceptance criteria | |

| 8.7 Control of nonconforming | |

| 8.7.1 | |

| 8.7.1.1 Customer authorization for concession | |

| 8.7.1.2 Control of nonconforming product—customer-specified process | |

| 8.7.1.3 Control of suspect product | |

| 8.7.1.4 Control of reworked product | |

| 8.7.1.5 Control of repaired product | |

| 8.7.1.6 Customer notification | |

| 8.7.1.7 Nonconforming product disposition | |

| 8.7.2 | |

| All clauses No. 9—III. phase CHECK | 9 Performance evaluation |

| 9.1 Monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation | |

| 9.1.1 General | |

| 9.1.1.1 Monitoring and measurement of manufacturing processes | |

| 9.1.1.2 Identification of statistical tools | |

| 9.1.1.3 Application of statistical concepts | |

| 9.1.2 Customer satisfaction | |

| 9.1.2.1 Customer satisfaction—supplemental | |

| 9.1.3 Analysis and evaluation | |

| 9.1.3.1 Prioritization | |

| 9.2 Internal audit | |

| 9.2.1 | |

| 9.2.2 | |

| 9.2.2.1 Internal audit program | |

| 9.2.2.2 QMS audit | |

| 9.2.2.3 Manufacturing process audit | |

| 9.2.2.4 Product audit | |

| 9.3 Management review | |

| 9.3.1 General | |

| 9.3.1.1 Management review—supplemental | |

| 9.3.2 Management review inputs | |

| 9.3.2.1 Management review inputs—supplemental | |

| 9.3.3 Management review outputs | |

| 9.3.3.1 Management review outputs—supplemental | |

| All clauses No. 10—IV. phase ACT | 10 Improvement |

| 10.1 General | |

| 10.2 Nonconformity and corrective action | |

| 10.2.1 | |

| 10.2.2 | |

| 10.2.3 Problem solving | |

| 10.2.4 Error-proofing | |

| 10.2.5 Warranty MS | |

| 10.2.6 Customer complaints and field failure test analysis | |

| 10.3 Continual improvement | |

| 10.3.1 Continual improvement—supplemental | |

| Annex A: Control Plan | |

| A.1 Phases of the control plan | |

| (a) Prototype | |

| (b) Pre-launch | |

| (c) Production | |

| A.2 Elements of the control plan | |

| General data | |

| Product control | |

| Process control | |

| Methods | |

| Reaction plan | |

| Annex B: Bibliography—supplemental automotive | |

| Internal audit | |

| Nonconformity and corrective action | |

| Measurement system analysis | |

| Product approval | |

| Product design | |

| Product control | |

| QMS administration | |

| Risk analysis | |

| SW process assessment | |

| Statistical tools | |

| Supplier quality management | |

| Health and Safety |

| Number of ISO Standard | Year of Publication | Title of Standard for Management Systems (MSs) | Requirements {R} Guidance for Use {G} | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10012 | 2003 | Measurement MSs | {R} for measurement processes and measuring equipment | [28] |

| 14001 | 2015 | Environmental MSs | {R} with {G} | [29] |

| 27001 1 | 2013 | Information technology—Security techniques— Information security MSs | {R} | [30] |

| 22301 | 2019 | Security and resilience—Business continuity MSs | {R} | [31] |

| 28000 | 2007 | Specification for security MSs for the supply chain | [32] | |

| 28001 | 2007 | Security MSs for the supply chain—Best practices for implementing supply chain security, assessments and plans | {R} and guidance | [33] |

| 28002 | 2011 | Security MSs for the supply chain—Development of resilience in the supply chain | {R} with {G} | [34] |

| 30301 | 2019 | Information and documentation—MSs for records | {R} | [35] |

| 37301 | 2021 | Compliance MSs | {R} with {G} | [36] |

| 39001 | 2012 | Road traffic safety (RTS) MSs | {R} with {G} | [37] |

| 44001 | 2017 | Collaborative business relationship MSs | {R} and framework | [38] |

| 50001 | 2018 | Energy MSs | {R} with {G} | [39] |

| 56001 2 | 202X | Innovation management—Innovation MSs | {R} with {G} | [40] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pauliková, A. Visualization Concept of Automotive Quality Management System Standard. Standards 2022, 2, 226-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards2020017

Pauliková A. Visualization Concept of Automotive Quality Management System Standard. Standards. 2022; 2(2):226-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards2020017

Chicago/Turabian StylePauliková, Alena. 2022. "Visualization Concept of Automotive Quality Management System Standard" Standards 2, no. 2: 226-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards2020017