Protein and Polysaccharide Complexes for Alleviating Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials for Complex Preparation and Sour Cream and Yogurt Production

2.2. Complex Preparation

2.3. Complex Characterization

2.4. Evaluation of Antifreeze Activity of Complexes in Dairy Products

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH) of the Polysaccharide and Protein Hydrolysates

3.2. Ice Recrystallization Inhibition (IRI) Activity of Protein–Polysaccharide and Hydrolysate Complexes

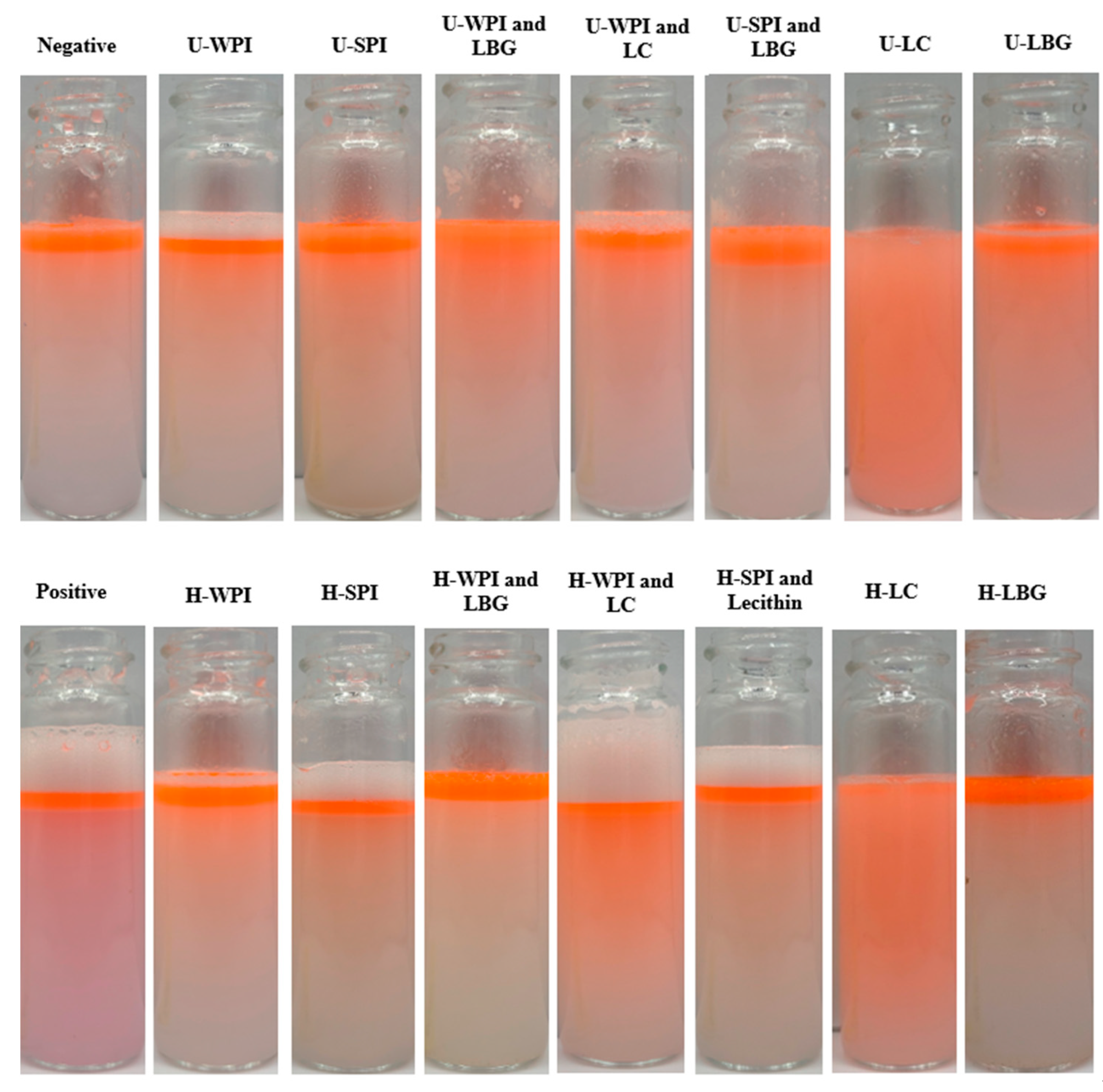

3.3. Amphiphilicity of Complexes Determined by Emulsification and Stability

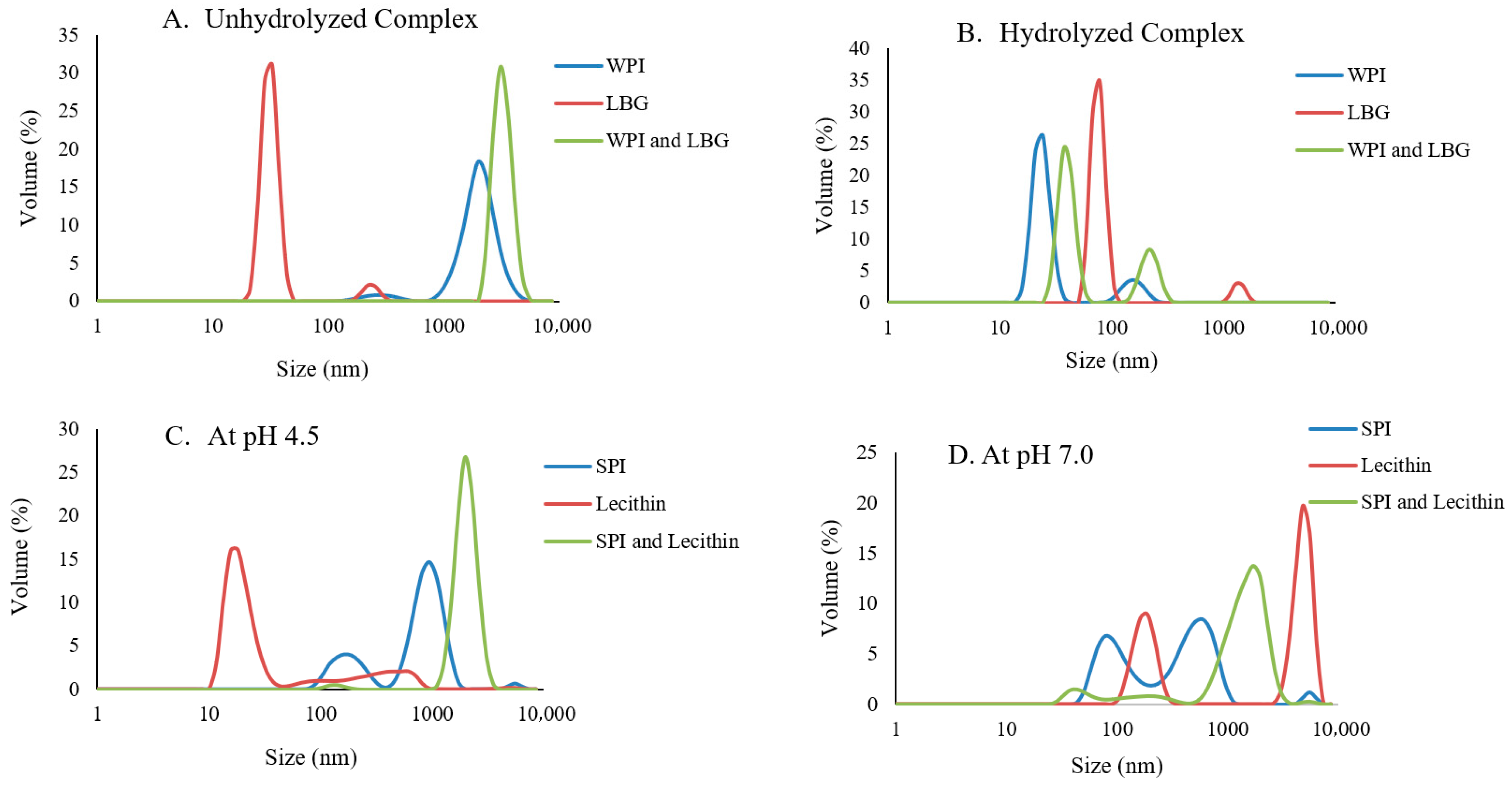

3.4. Particle Size Analysis of Unhydrolyzed and Hydrolyzed Complexes

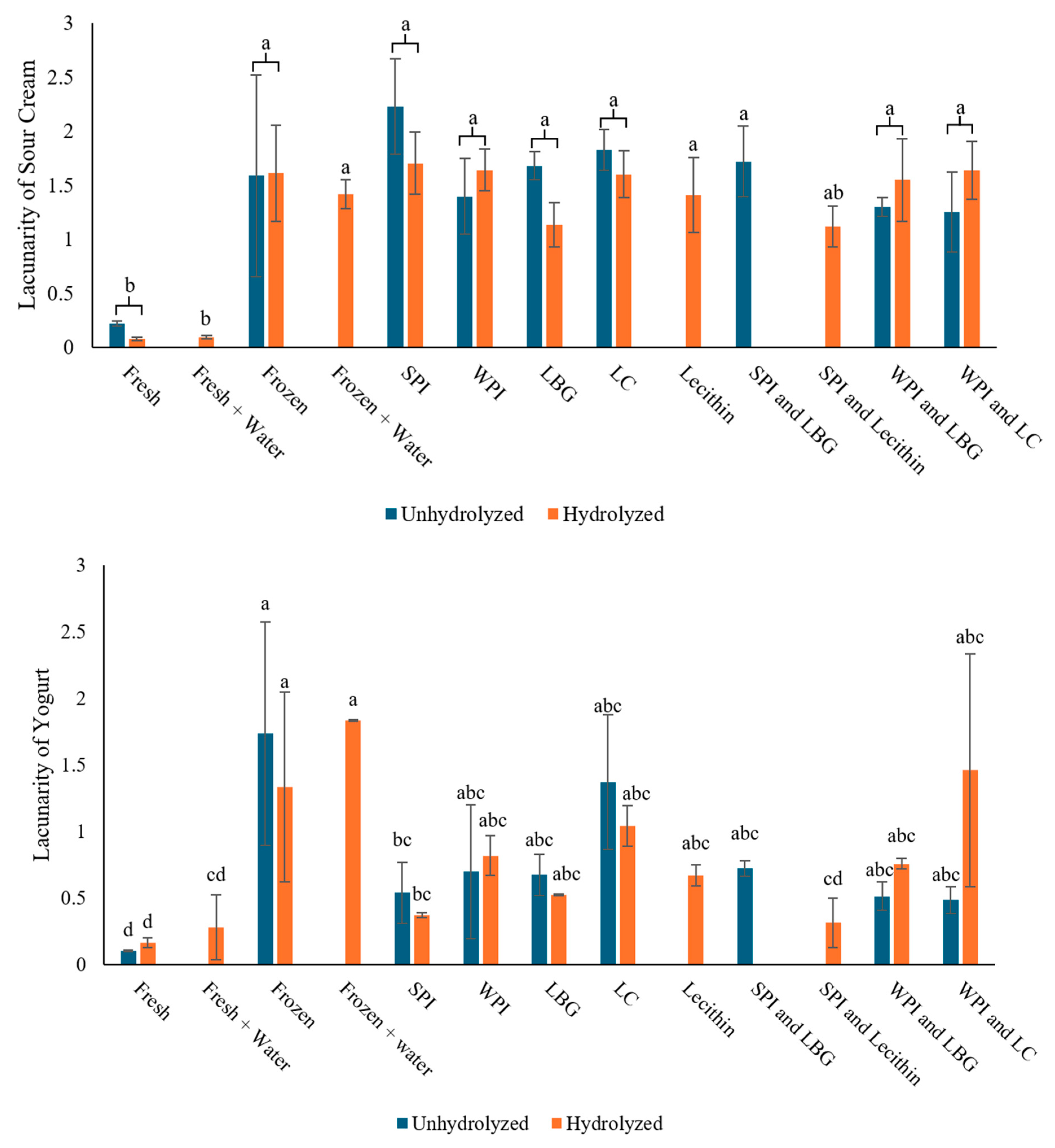

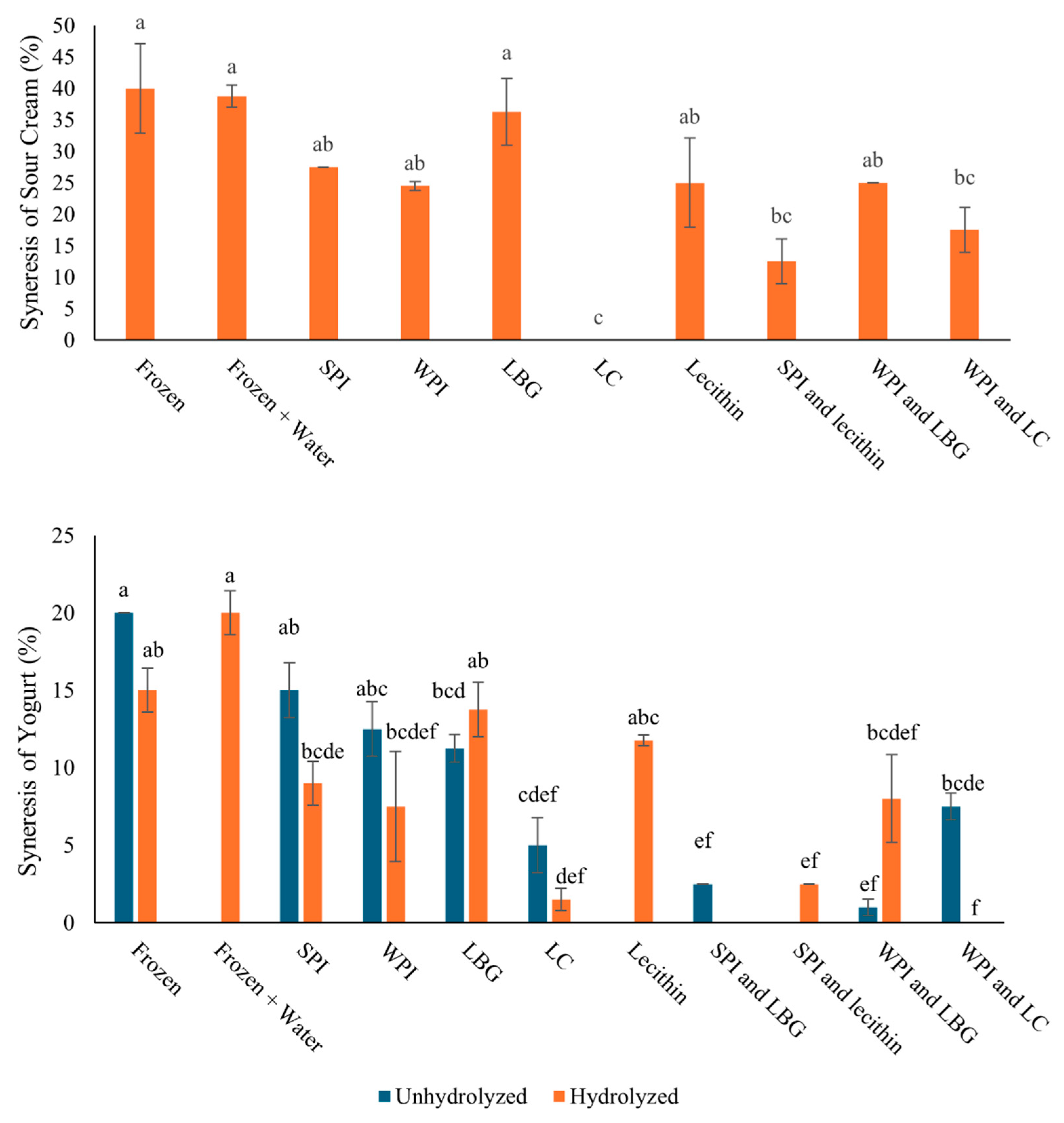

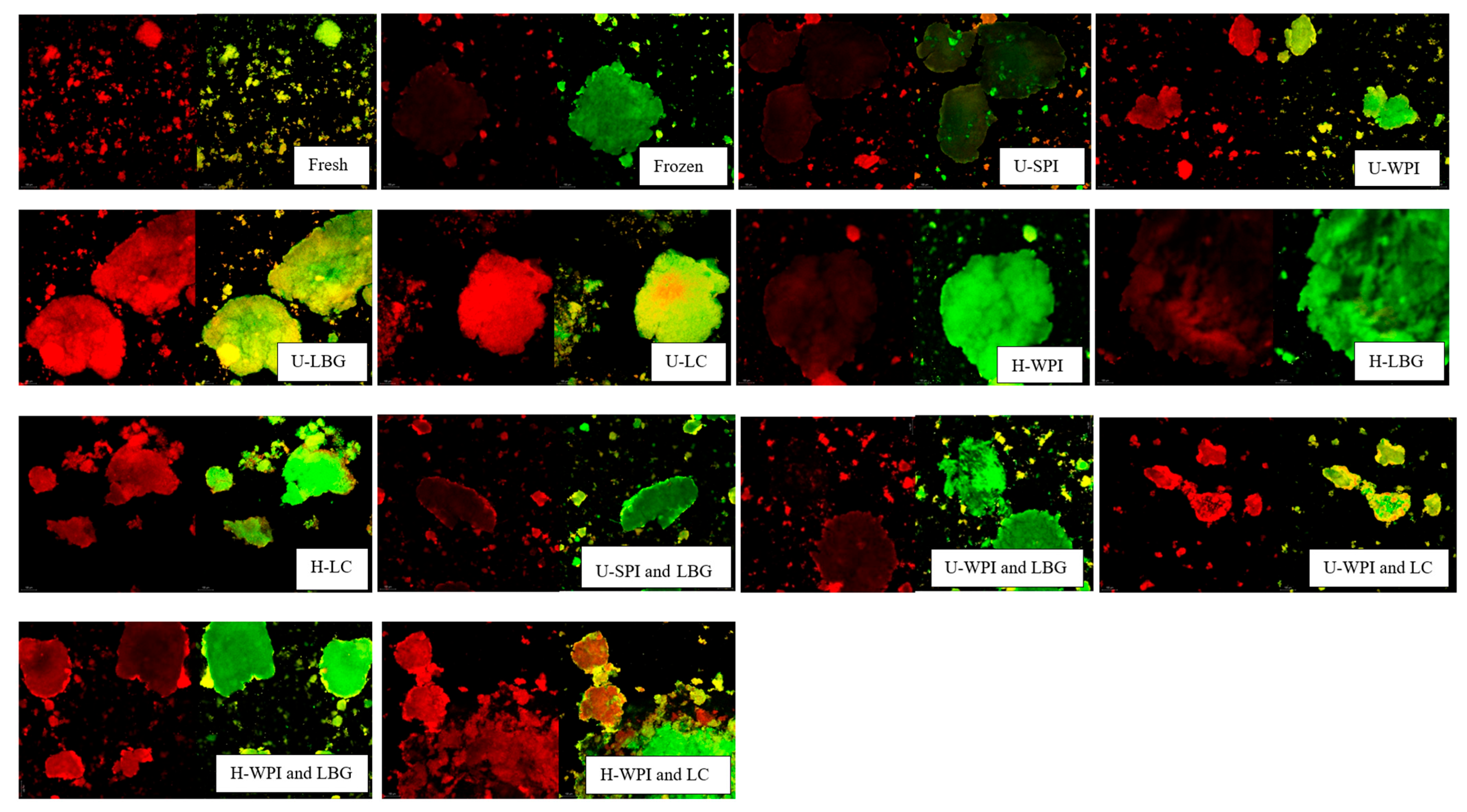

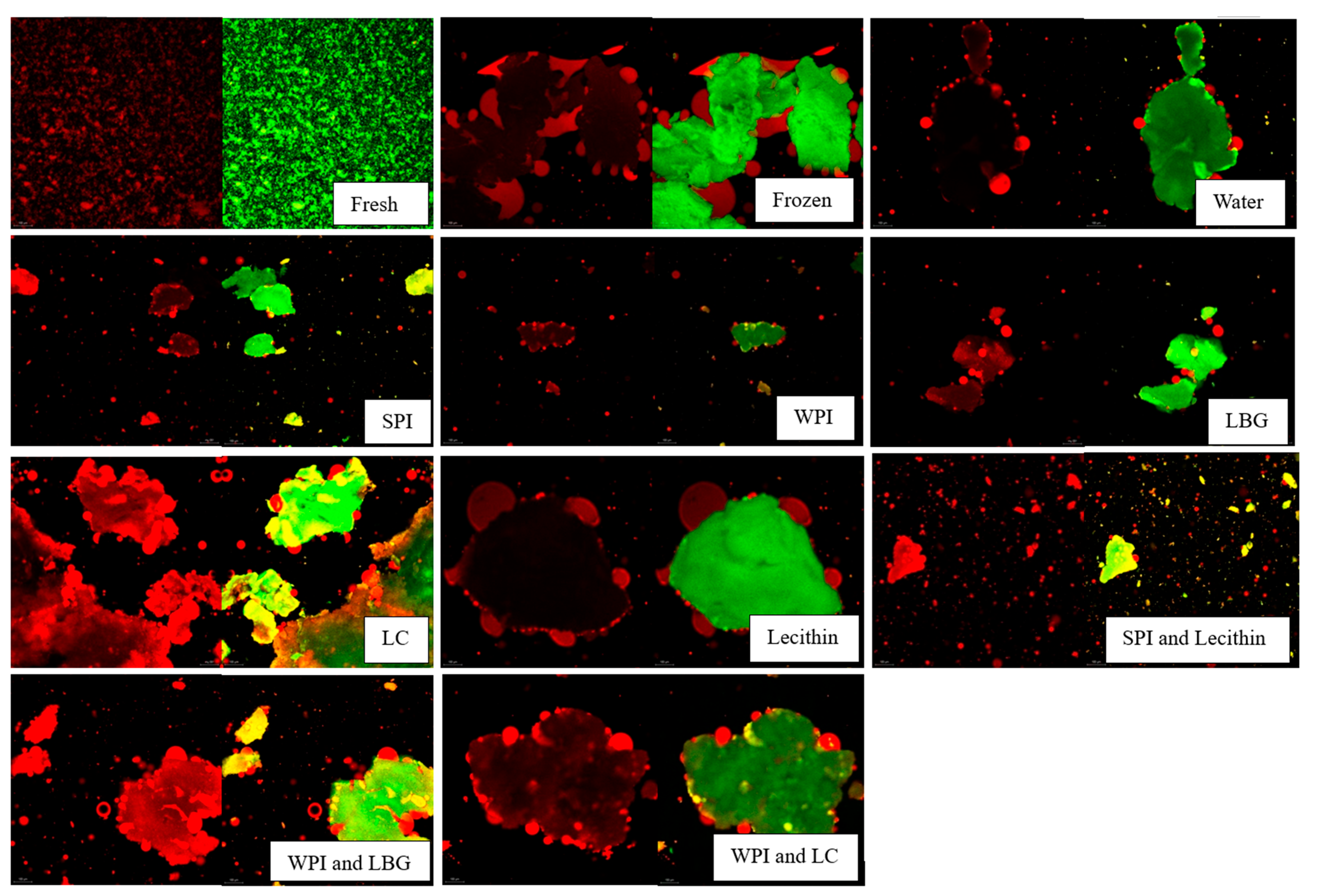

3.5. Effect of Protein–Polysaccharide Complexes on Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diefes, H.A.; Rizvi, S.S.H.; Boonyaratanakornkit, B.J. Rheological behavior of frozen and thawed low-moisture, part-skim Mozzarella cheese. J. Food Sci. 1993, 58, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinovi, M.; Mucchetti, G.; Wiking, L.; Corredig, M. Freezing as a solution to preserve the quality of dairy products: The case of milk, curds and cheese. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 3340–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Song, Z.; Chen, X. A review of natural polysaccharides for food cryoprotection: Ice crystals inhibition and cryo-stabilization. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2022, 27, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.-I.; Gunasekaran, S. Effect of freezing and frozen storage on microstructure of Mozzarella and pizza cheeses. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol.-Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinovi, M.; Corredig, M.; Mucchetti, G.; Carini, E. Water status and dynamics of high-moisture Mozzarella cheese as affected by frozen and refrigerated storage. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodaran, S.; Wang, S. Ice crystal growth inhibition by peptides from fish gelatin hydrolysate. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 70, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, M.W.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Wu, T. Corn cob hemicelluloses as stabilizer for ice recrystallization inhibition in ice cream. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 318, 121127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinovi, M.; Mucchetti, G. Effect of freezing and thawing processes on high-moisture Mozzarella cheese rheological and physical properties. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol.-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 124, 109137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atici, O.; Nalbantoglu, B. Antifreeze proteins in higher plants. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venketesh, S.; Dayananda, C. Properties, potentials, and prospects of antifreeze proteins. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2008, 28, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budke, C.; Koop, T. Ice recrystallization inhibition and molecular recognition of ice faces by poly(vinyl alcohol). ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomich, M.; Día, V.P.; Premadasa, U.I.; Doughty, B.; Krishnan, H.B.; Wang, T. Ice recrystallization inhibition activity of soy protein hydrolysates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 11587–11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Guo, R.; Kou, Y.; Song, H.; Zhan, T.; Wu, J.; Song, L.; Zhang, H.; Xie, F.; Wang, J.; et al. Inhibition of ice recrystallization by tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed polysaccharide and molecular weight effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 301, 120358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Matusiak, M.; Samborska, K.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Gondek, E.; Jakubczyk, E.; Antczak, A. The influence of kappa carrageenan and its hydrolysates on the recrystallization process in sorbet. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredig, M.; Sharafbafi, N.; Kristo, E. Polysaccharide–protein interactions in dairy matrices, control and design of structures. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Jafari, S.M. Recent advances in application of different hydrocolloids in dairy products to improve their techno-functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, T. How Yogurt is Processed. 2015. Available online: https://www.ift.org/news-and-publications/food-technology-magazine/issues/2015/december/columns/processing (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Schmitt, C.; Sanchez, C.; Desobry-Banon, S.; Hardy, J. Structure and technofunctional properties of protein-polysaccharide complexes: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 689–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monalisa, K.; Shibata, M.; Hagiwara, T. Ice recrystallization behavior of corn starch/sucrose solutions: Effects of addition of corn starch and antifreeze protein III. Food Biophys. 2021, 16, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaukel, V.; Leiter, A.; Spies, W.E.L. Synergism of different fish antifreeze proteins and hydrocolloids on recrystallization inhibition of ice in sucrose solutions. J. Food Eng. 2014, 141, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monalisa, K.; Shibata, M.; Hagiwara, T. Ice recrystallization inhibition behavior by wheat flour and its synergy effect with antifreeze protein III. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 143, 108882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollis, A.; Wang, T.; Dia, V.P. Hemp protein hydrolysates’ ability to inhibit ice recrystallization is influenced by the dispersing medium and succinylation. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Dia, V.P.; Wang, T. The ice recrystallization inhibition activity of wheat glutenin hydrolysates and effect of salt on their activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 154, 110153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomich, M.D.; Wang, T. Characterization of soy protein hydrolysate and lecithin complex for its novel antifreeze activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1944, 153, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, C.; Dia, V.; Eckelkamp, L.; Wang, T. Complexing whey protein isolate with polysaccharide to ameliorate freezing-induced damage of cream cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2025, 78, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhong, Q. Stable casein micelle dispersions at pH 4.5 enabled by propylene glycol alginate following a pH-cycle treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 233, 115834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.A.; Hallett, J.; DeVries, A.L. Solute effects on ice recrystallization: An assessment technique. Cryobiology 1988, 25, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, J.; Fomich, M.; Día, V.P.; Wang, T. A novel automated protocol for ice crystal segmentation analysis using Cellpose and Fiji. Cryobiology 2023, 111, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karperien, A. FracLac for ImageJ. Introduction.htm; (1999–2013). Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/plugins/fraclac/FLHelp/FLCitations.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Yoon, L.W.; Ang, T.N.; Ngoh, G.C.; Chua, A.S.M. Fungal solid-state fermentation and various methods of enhancement in cellulase production. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 67, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Parkin, K.L. Fennema’s Food Chemistry; Taylor & Francis Group: Milton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, S.; Mudgil, D. Locust bean gum: Processing, properties and food applications—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, A.K.; Chandrasekhar, G.; Silva, M.B.; Silvério da Silva, S. The realm of cellulases in biorefinery development. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Siar, E.-H.; Tavano, O.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Use of Alcalase in the production of bioactive peptides: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2143–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regand, A.; Goff, H.D. Ice recrystallization inhibition in ice cream as affected by ice structuring proteins from winter wheat grass. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midya, U.S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Ice recrystallization unveils the binding mechanism operating at a diffused interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; de Vries, R. Interfacial stabilization using complexes of plant proteins and polysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 21, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarpa-Parra, M.; Tian, Z.; Temelli, F.; Zeng, H.; Chen, L. Understanding the stability mechanisms of lentil legumin-like protein and polysaccharide foams. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Gao, L.; Geng, Q.; Li, T.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Dai, T. Effects of moderate enzymatic hydrolysis on structure and functional properties of pea protein. Foods 2022, 11, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, C.M.; Vermeir, L.; Rebry, F.; Kerkaert, B.; Van der Meeren, P.; Guinee, T.P. Impact of freezing on the physicochemical and functional properties of low–moisture part–skim mozzarella. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 106, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graiver, N.G.; Zaritzky, N.E.; Califano, A.N. Viscoelastic behavior of refrigerated frozen low-moisture Mozzarella cheese. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, FEP123–FEP128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Perfect, E.; Dunne, W.M.; Odling, N.; Kim, J.-W. Lacunarity analysis of fracture networks: Evidence for scale-dependent clustering. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

represents 20 microns.

| Reducing Sugar Content (mg/mL) | DH (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | ||

| LBG | 0.01 ± 0.00 c | 0.30 ± 0.00 a | 2.86 a |

| LC | 0.01 ± 0.00 c | 0.22 ± 0.01 b | 2.08 b |

| Peptide Size Distribution (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Time (min) | <1 kDa | 1–5 kDa | 5–10 kDa | >10 kDa |

| SPI | 0 | 20.8 | 18.9 | 9.3 | 51.1 |

| 2 | 59.0 | 25.9 | 9.5 | 5.7 | |

| 5 | 66.6 | 19.4 | 10.6 | 3.3 | |

| 10 | 54.6 | 26.1 | 9.1 | 10.2 | |

| WPI | 0 | 0.3 | 19.8 | 2.0 | 78.0 |

| 2 | 51.8 | 25.7 | 10.9 | 11.7 | |

| 5 | 52.4 | 25.8 | 9.9 | 11.9 | |

| 10 | 65.3 | 20.8 | 7.8 | 8.3 | |

| Ice Crystal Size Reduction Relative to PEG (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.5 | pH 7.0 | |||

| Controls | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed |

| SPI | −17.94 ± 9.60 c | −15.70 ± 12.19 c | 10.50 ± 14.51 cd | 7.71 ± 7.91 cde |

| WPI | −15.35 ± 0.55 c | −15.72 ± 7.74 c | 1.43 ± 2.80 cde | 3.55 ± 7.72 cde |

| LBG | −27.16 ± 16.11 c | −28.89 ± 9.40 c | 7.24 ± 4.65 cde | −26.92 ± 7.81 e |

| LC | −30.69 ± 8.50 c | −26.69 ± 4.31 c | −2.10 ± 3.66 cde | 16.23 ± 7.05 cd |

| Lecithin | −39.11 ± 10.71 c | — | −3.25 ± 18.36 cde | — |

| Complexes | ||||

| SPI and LBG | 37.80 ± 7.69 a | — | 30.74 ± 13.36 abc | — |

| WPI and LBG | 33.51 ± 19.60 ab | −6.45 ± 9.29 bc | 63.91 ± 3.28 a | −1.15 ± 3.88 cde |

| WPI and LC | −19.71 ± 6.80 c | 0.79 ± 9.50 abc | −8.36 ± 9.01 cde | 21.51 ± 5.82 bcd |

| SPI and Lecithin | — | 27.43 ± 4.25 ab | — | 54.98 ± 2.51 ab |

| Mean Particle Diameter (nm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.5 | pH 7 | |||

| Controls | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed |

| SPI | — | 332 ± 26 e | — | 245 ± 6 f |

| WPI | 2113 ± 61 c | 2609 ± 154 c | 574 ± 45 cde | 274 ± 88 ef |

| LBG | 1053 ± 289 d | 1168 ± 521 d | 1069 ± 218 bcd | 3260 ± 1069 a |

| LC | — | 713 ± 180 d | — | 2216 ± 1331 ab |

| Lecithin | 263 ± 2 e | — | 1207 ± 293 bc | — |

| Complexes | ||||

| SPI and Lecithin | — | 1095 ± 130 d | — | 382 ± 17 ef |

| WPI and LBG | 10,174 ± 2230 a | 5890 ± 1614 ab | 4196 ± 733 a | 487 ± 110 def |

| WPI and LC | — | 3174 ± 78 bc | — | 493 ± 44 def |

| Firmness (g) | Cohesiveness (g) | Consistency (g.sec) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed |

| Fresh | 53.35 ± 0.42 a | 64.41 ± 8.70 a | −32.89 ± 0.82 a | −41.70 ± 4.98 a | 333.81 ± 0.67 ab | 385.33 ± 29.98 a |

| Fresh + Water | — | 60.14 ± 8.98 a | — | −36.62 ± 6.44 a | — | 360.35 ± 45.52 a |

| Frozen | 25.92 ± 0.28 cd | 29.67 ± 0.23 bc | −3.53 ± 0.25 bcd | −3.51 ± 0.11 bcd | 110.30 ± 1.24 def | 115.43 ± 2.34 def |

| Frozen + Water | — | 22.93 ± 2.99 cd | — | −3.35 ± 0.00 bcd | — | 108.73 ± 4.33 def |

| SPI | 15.66 ± 0.90 e | 16.81 ± 0.40 de | −3.08 ± 0.17 d | −3.49 ± 0.14 bcd | 99.46 ± 3.58 f | 99.10 ± 2.12 f |

| WPI | 15.96 ± 0.93 de | 17.15 ± 0.31 de | −3.65 ± 0.51 bcd | −3.59 ± 0.00 bcd | 97.46 ± 3.16 f | 99.42 ± 2.28 f |

| LBG | 15.54 ± 0.37 e | 18.83 ± 1.78 cde | −3.79 ± 0.34 bcd | −3.63 ± 0.17 bcd | 98.04 ± 1.46 f | 100.71 ± 2.84 f |

| LC | 31.07 ± 12.20 bc | 58.13 ± 5.79 a | −5.51 ± 0.23 b | −5.29 ± 0.48 bc | 148.99 ± 35.83 cd | 247.27 ± 28.59 b |

| Lecithin | — | 18.99 ± 1.04 cde | — | −3.20 ± 0.11 cd | — | 103.04 ± 1.12 ef |

| Complexes | ||||||

| SPI and LBG | 16.36 ± 2.29 de | — | −5.59 ± 2.32 bc | — | 104.08 ± 9.45 ef | — |

| SPI and Lecithin | — | 15.04 ± 0.37 e | — | −3.29 ± 0.20 bcd | — | 100.42 ± 2.59 f |

| WPI and LBG | 15.44 ± 0.71 | 16.04 ± 0.59 de | −4.79 ± 0.73 bcd | −3.49 ± 0.08 bcd | 98.78 ± 2.60 f | 97.09 ± 0.21 f |

| WPI and LC | 44.00 ± 8.56 ab | 29.61 ± 2.29 bc | −4.77 ± 1.16 bcd | −4.47 ± 0.00 bcd | 163.76 ± 13.50 c | 139.31 ± 4.88 cde |

| Firmness (g) | Cohesiveness (g) | Consistency (g.sec) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed | Unhydrolyzed | Hydrolyzed |

| Fresh | 28.16 ± 4.63 abc | 33.15 ± 3.39 ab | −13.88 ± 3.53 a | −15.62 ± 1.86 a | 170.71 ± 33.03 ab | 204.75 ± 22.18 ab |

| Fresh + Water | — | 28.49 ± 3.08 abc | — | −13.82 ± 2.03 a | — | 177.07 ± 22.85 ab |

| Frozen | 16.10 ± 1.13 ef | 14.36 ± 0.31 f | −2.96 ± 0.11 d | −3.31 ± 0.23 d | 104.81 ± 1.36 d | 96.22 ± 1.32 d |

| Frozen + Water | — | 15.34 ± 0.56 f | — | −2.88 ± 0.23 d | — | 103.19 ± 0.64 d |

| SPI | 14.88 ± 0.14 f | 15.06 ± 0.23 f | −3.06 ± 0.31 d | −3.35 ± 0.56 d | 103. 04 ± 0.04 d | 103.48 ± 0.91 d |

| WPI | 14.98 ± 0.11 f | 14.82 ± 0.11 f | −3.08 ± 0.11 d | −3.41 ± 0.54 d | 103.30 ± 0.08 d | 101.59 ± 0.33 d |

| LBG | 14.78 ± 0.11 f | 15.56 ± 0.14 f | −3.87 ± 0.06 cd | −3.37 ± 0.03 d | 100.86 ± 1.00 d | 105.41 ± 0.59 d |

| LC | 25.76 ± 4.41 bcd | 21.07 ± 0.25 cde | −6.03 ± 0.45 bc | −4.33 ± 0.37 cd | 151.61 ± 23.57 bc | 123.26 ± 0.54 cd |

| Lecithin | — | 15.46 ± 0.40 f | — | −3.00 ± 0.45 d | — | 104.30 ± 1.88 d |

| Complexes | ||||||

| SPI and LBG | 14.94 ± 0.51 f | — | −4.47 ± 0.11 cd | — | 100.45 ± 4.04 d | — |

| SPI and Lecithin | — | 16.12 ± 0.08 ef | — | −4.35 ± 0.06 cd | — | 105.68 ± 2.46 d |

| WPI and LBG | 15.10 ± 0.11 f | 14.70 ± 0.28 f | −4.55 ± 0.17 cd | −3.28 ± 0.11 d | 101.12 ± 0.20 d | 100.95 ± 0.57 d |

| WPI and LC | 19.13 ± 2.20 def | 37.18 ± 4.35 a | −4.45 ± 0.65 cd | −10.28 ± 3.47 ab | 116.10 ± 9.59 cd | 218.47 ± 30.76 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaughan, R.; Dia, V.; Eckelkamp, E.; Wang, T. Protein and Polysaccharide Complexes for Alleviating Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt. Foods 2025, 14, 4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244193

Vaughan R, Dia V, Eckelkamp E, Wang T. Protein and Polysaccharide Complexes for Alleviating Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244193

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaughan, Ripley, Vermont Dia, Elizabeth Eckelkamp, and Tong Wang. 2025. "Protein and Polysaccharide Complexes for Alleviating Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt" Foods 14, no. 24: 4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244193

APA StyleVaughan, R., Dia, V., Eckelkamp, E., & Wang, T. (2025). Protein and Polysaccharide Complexes for Alleviating Freeze-Induced Damage in Sour Cream and Yogurt. Foods, 14(24), 4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244193