Multi-Omics Elucidation of Flavor Characteristics in Compound Fermented Beverages Based on Flavoromics and Metabolomics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Wine Quality Analysis

2.3. Brewing Methodology

2.4. Flavor Compound Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

2.6. Relative Odor Activity Value (rOAV) Analysis

2.7. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

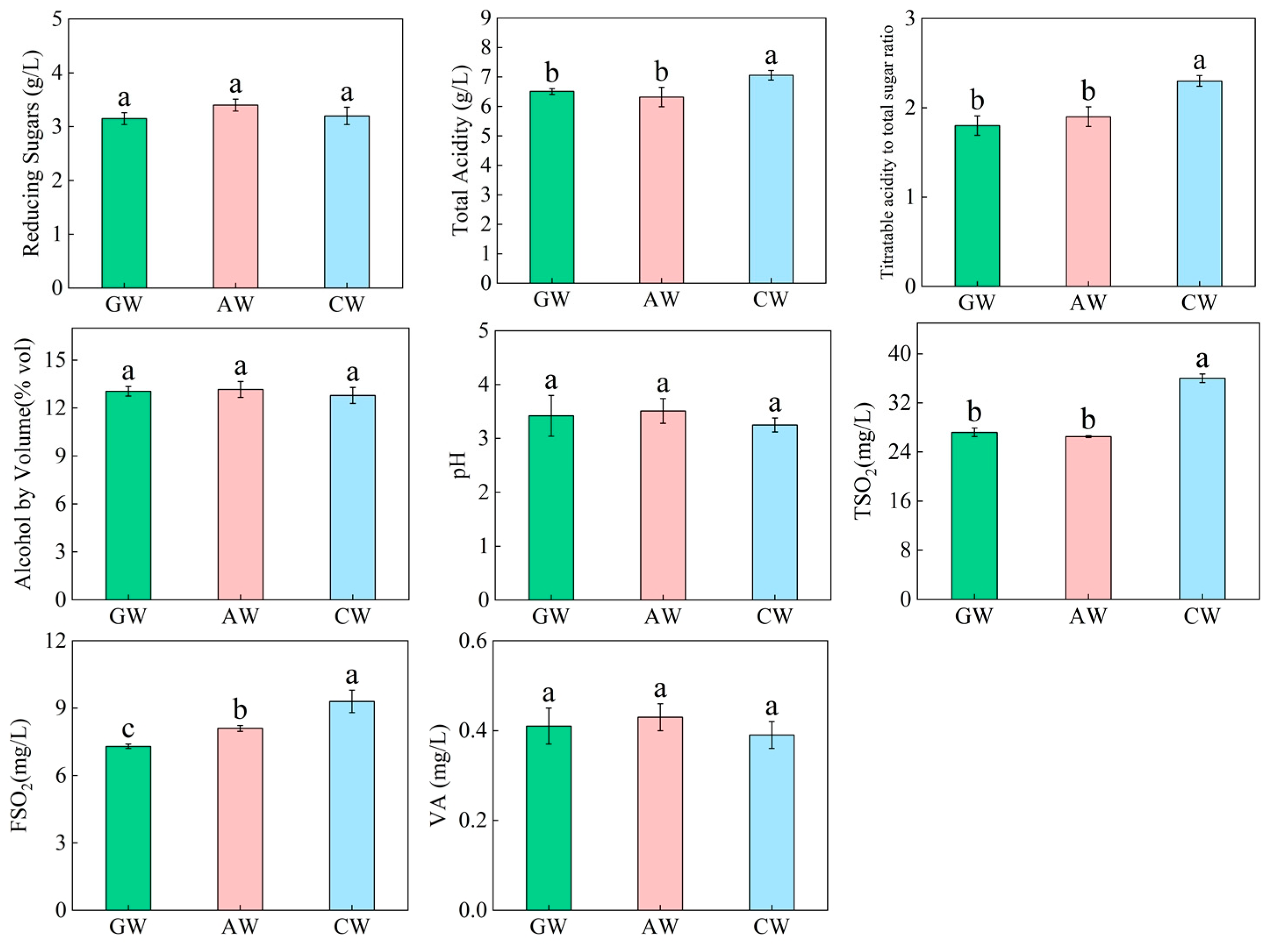

3.1. Basic Quality Parameters of the Three Compound Fermented Beverages

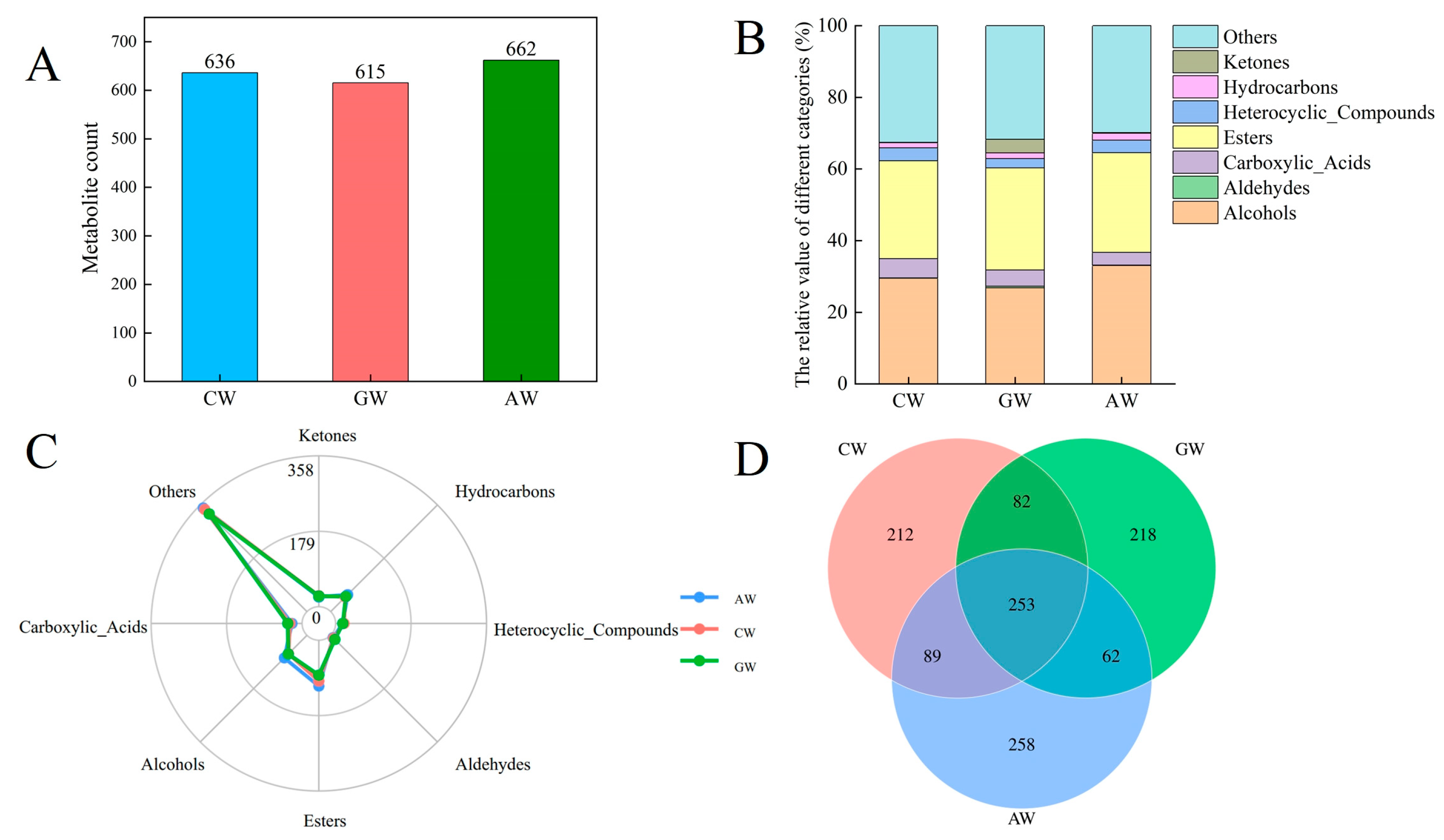

3.2. Flavor Compound Composition and Proportions in the Three Compound Fermented Beverages

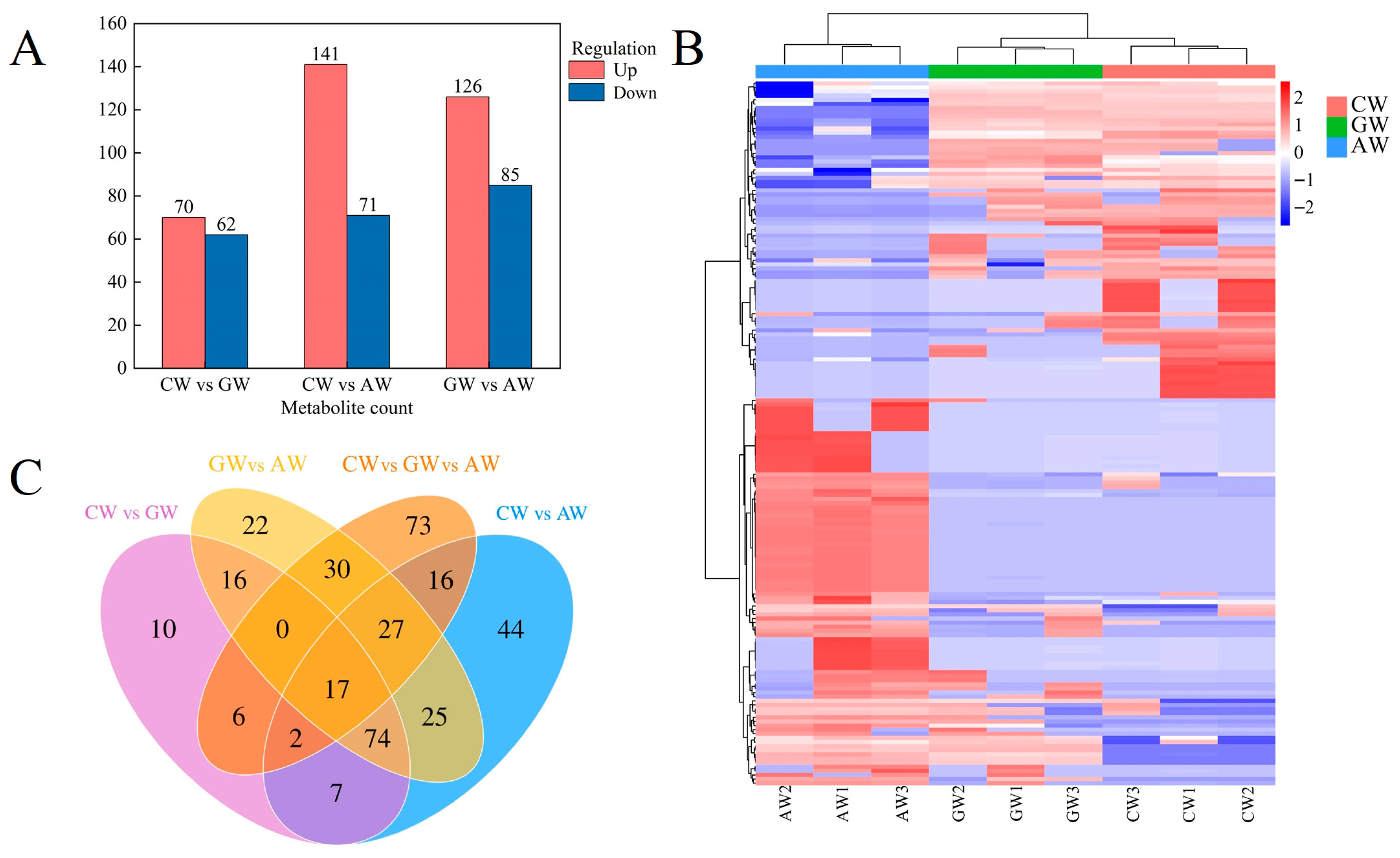

3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Flavor Compounds

3.4. Differential Flavor Compound Analysis

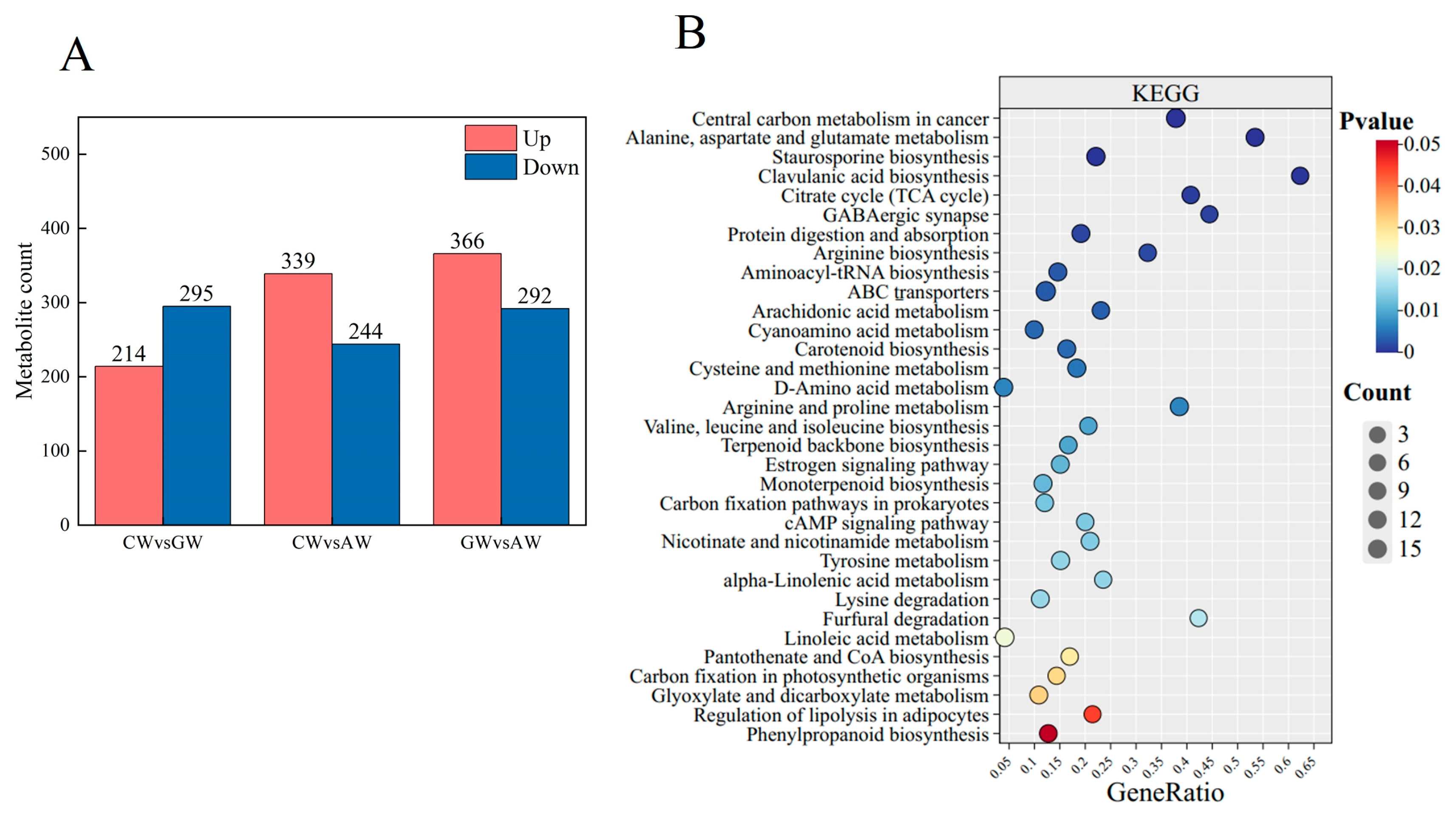

3.5. Characterization of Non-Volatile Compounds

3.6. Network Interactions Between VOCs and Sensory Aroma Attributes

3.7. Compound Fermented Beverage Aroma rOAV

3.8. Correlations Among VOCs, Wine Physicochemical Properties, and Metabolites

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Basic Physicochemical Properties

4.2. Metabolic Pathways of Aroma Compounds

4.3. Evaluation of Aroma Compounds via rOAVs

4.4. Research Value of Compound Fermented Beverage

4.5. Link Between Flavor and Matrix: Correlations of rOAV Compounds with Physicochemical Indices

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, L.; Yan, Y.; Wu, M.; Ke, L. Advances in the quality improvement of compound fermented beverages: A review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Li, F.; Song, M.; Li, Z.; Pan, C. Optimization of fermentation technology for composite fruit and vegetable wine by response surface methodology and analysis of its aroma components. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 35616–35626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keșa, A.L.; Pop, C.R.; Mudura, E.; Salanță, L.C.; Pasqualone, A.; Dărab, C.; Coldea, T.E. Strategies to improve the potential functionality of fruit-based fermented beverages. Plants 2021, 10, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lu, Y.; He, Q. Unlocking the microbial mechanisms in fermented bean products: Advances and future directions in multi-omics and machine learning approaches. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ru, S.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Lyu, X. Effects of alcoholic fermentation on the non-volatile and volatile compounds in grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Mac. cv. Cocktail) juice: A combination of UPLC-MS/MS and gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1015924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, F. Use of Exogenous Enzymes to Liberate Monoterpene and Thiol Precursors from Hops and Their Ability to Modulate Flavor in Pale Ale Style Beers. Master’s Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.; Qu, T.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, H. Research progress on aroma enhancement strategies for fruit wine. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2025, 5, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yang, C.; Yang, Y.; Peng, B. Analysis of the formation of characteristic aroma compounds by amino acid metabolic pathways during fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecules 2023, 28, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramithiotis, S.; Stasinou, V.; Tzamourani, A.; Kotseridis, Y.; Dimopoulou, M. Malolactic fermentation—Theoretical advances and practical considerations. Fermentation 2022, 8, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, D.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, C. Characteristic of volatile flavor compounds in ‘Fengtangli’ plum (Prunus salicina Lindl.) were explored based on GC× GC-TOF MS. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1536954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Cheng, W.; Jiang, C.; Pan, T.; Li, N.; Li, M.; Du, X. Machine-Learning-Assisted Aroma Profile Prediction in Five Different Quality Grades of Nongxiangxing Baijiu Fermented During Summer Using Sensory Evaluation Combined with GC× GC–TOF-MS. Foods 2025, 14, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Nie, X.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ao, C. Analysis of flavor-related compounds in fermented persimmon beverages stored at different temperatures. LWT 2022, 163, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Cheng, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Comparison of flavor differences between the juices and wines of four strawberry cultivars using two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry and sensory evaluation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Tian, H. Aroma generation of fermented compound fermented beverages: Potential enhancement strategies via fermentation and aging process. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 9004–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, K.; Lui, A.C.; Zhang, S.; Peck, G.M. Folin-Ciocâlteu, RP-HPLC (reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography), and LC-MS (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) provide complementary information for describing cider (Malus spp.) apple juice. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuengchamnong, N.; Saesong, T.; Ingkaninan, K.; Wittaya-areekul, S. Antioxidant Activity and Chemical Constituents Identification by LC-MS/MS in Bio-fermented Fruit Drink of Morinda citrifolia L. Trends Sci. 2023, 20, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y. Untargeted metabolomics combined with chemometrics reveals distinct metabolic profiles across two sparkling cider fermentation stages. Food Res. Int. 2024, 195, 114946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Cheng, L. Developmental changes of carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, and phenolic compounds in ‘Honeycrisp’ apple flesh. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Salvi, L.; Paoli, F.; Fucile, M.; Mattii, G.B. Effect of agronomic techniques on aroma composition of white grapevines: A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morariu, P.A.; Mureșan, A.E.; Sestras, A.F.; Tanislav, A.E.; Dan, C.; Mareși, E.; Militaru, M.; Mureșan, V.; Sestras, R.E. A Comprehensive Morphological, Biochemical, and Sensory Study of Traditional and Modern Apple Cultivars. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 15038-2006; Analytical Methods of Wine and Fruit Wine. National Standard of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Song, X.; Ling, M.; Li, D.; Zhu, B.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C.; Lan, Y. Volatile profiles and sensory characteristics of Cabernet Sauvignon dry red wines in the sub-regions of the eastern foothills of Ningxia Helan Mountain in China. Molecules 2022, 27, 8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jeleń, H.H. Comprehensive two dimensional gas chromatography–time of flight mass spectrometry (GC× GC-TOFMS) for the investigation of botanical origin of raw spirits. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Piergiovanni, M.; Franceschi, P.; Mattivi, F.; Vrhovsek, U.; Carlin, S. Application of comprehensive 2D gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry in beer and wine VOC analysis. Analytica 2023, 4, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welke, J.E.; Hernandes, K.C.; Nicolli, K.P.; Barbará, J.A.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; Zini, C.A. Role of gas chromatography and olfactometry to understand the wine aroma: Achievements denoted by multidimensional analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Li, J.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X.; Ge, Q. Aroma Identification and Traceability of the Core Sub-Producing Area in the Helan Mountain Eastern Foothills Using Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography and Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry and Chemometrics. Foods 2024, 13, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demurtas, A.; Pescina, S.; Nicoli, S.; Santi, P.; de Araujo, D.R.; Padula, C. Validation of a HPLC-UV method for the quantification of budesonide in skin layers. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1164, 122512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, L.; Tao, M.; Miao, L. Method development and validation for simultaneous determination of six tyrosine kinase inhibitors and two active metabolites in human plasma/serum using UPLC–MS/MS for therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 211, 114562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrtsi, E.D.; Koulocheri, S.D.; Iliopoulos, V.; Haroutounian, S.A. High-throughput quantification of 32 bioactive antioxidant phenolic compounds in grapes, wines and vinification byproducts by LC–MS/MS. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jia, Y.; Cai, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, R.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wen, L. Study on the relationship between flavor components and quality of ice wine during freezing and brewing of ‘beibinghong’ grapes. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Bottelli, P.; Corona, O.; Foschino, R.; Vigentini, I. Innovative alcoholic drinks obtained by co-fermenting grape must and fruit juice. Metabolites 2019, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcárcel-Muñoz, M.J.; Guerrero-Chanivet, M.; del Carmen Rodríguez-Dodero, M.; Butrón-Benítez, D.; de Valme García-Moreno, M.; Guillén-Sánchez, D.A. Analytical and chemometric characterization of sweet Pedro Ximénez Sherry wine during its aging in a criaderas y solera system. Foods 2023, 12, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabokbar, N.; Khodaiyan, F. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activities of pomegranate juice and whey based novel beverage fermented by kefir grains. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, F.; Zheng, M.; Sheng, L.; Shi, D.; Song, K. A Comprehensive Review of the Functional Potential and Sustainable Applications of Aronia melanocarpa in the Food Industry. Plants 2024, 13, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofalo, R.; Suzzi, G.; Perpetuini, G. Discovering the influence of microorganisms on wine color. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 790935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlček, J.; Jurikova, T.; Bednaříková, R.; Snopek, L.; Ercisli, S.; Tureček, O. The influence of sulfur dioxide concentration on antioxidant activity, total polyphenols, flavonoid content and individual polyphenolic compounds in white wines during storage. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Gong, J.; Tian, Y.; Ao, C.; Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Du, G. Comparison of microbial communities and volatile profiles of wines made from mulberry and grape. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5079–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. Assessment of wine quality, traceability and detection of grapes wine, detection of harmful substances in alcohol and liquor composition analysis. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 1377–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Jia, W. Extracellular proteolytic enzyme-mediated amino exposure and β-oxidation drive the raspberry aroma and creamy flavor formation. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, T.; Chen, D.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Z. Molecular regulatory mechanisms affecting fruit aroma. Foods 2024, 13, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ivanova-Petropulos, V.; Duan, C.; Yan, G. Effect of unsaturated fatty acids on intra-metabolites and aroma compounds of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in wine fermentation. Foods 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, G.; Chu, Y.; Yue, H.; Xu, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Jia, Y. Integrated Analysis of the Metabolome and Transcriptome During Apple Ripening to Highlight Aroma Determinants in Ningqiu Apples. Plants 2025, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, F.; Cai, W.; Peng, B.; Shan, C. Exploring jujube wine flavor and fermentation mechanisms by HS-SPME-GC–MS and UHPLC-MS metabolomics. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Effects of Vineyard Managements on Grape and Wine Quality in Response to Grapevine Red Blotch Disease. Ph.D. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Šikuten, I.; Štambuk, P.; Marković, Z.; Tomaz, I.; Preiner, D. Grape Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)-Analysis, Biosynthesis and Profiling. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3016–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.C.; Zhang, H.L.; Ma, X.R.; Xia, N.Y.; Duan, C.Q.; Yang, W.M.; Pan, Q.H. Leaching and evolution of anthocyanins and aroma compounds during Cabernet Sauvignon wine fermentation with whole-process skin-seed contact. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, I.; Ottaviano, E.; Corcione, G.; Digiorgio, C.; Fioschi, G.; Paradiso, V.M. Premature aging of red wines: A matter of fatty acid oxidation? A review on lipid-derived molecular markers and their possible precursors. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 8315–8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, A.; Scioli, G.; Della Valle, A.; Cichelli, A.; Novellino, E.; Bauer, M.; Kamysz, W.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Córdova, M.L.F.-D.; Castillo-López, R.; et al. Phenolic analysis and in vitro biological activity of red wine, pomace and grape seeds oil derived from Vitis vinifera L. cv. Montepulciano d’Abruzzo. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Bai, J.; Qiu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, K.; Gao, H. Insight into the characteristics of cider fermented by single and co-culture with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe based on metabolomic and transcriptomic approaches. Lwt 2022, 163, 113538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, J.L.; Schoumacker, R. Dynamic instrumental and sensory methods used to link aroma release and aroma perception: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Fan, B.; Hao, J.; Yao, Y.; Ran, S.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, R. Changes in Microbial Community Diversity and the Formation Mechanism of Flavor Metabolites in Industrial-Scale Spontaneous Fermentation of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines. Foods 2025, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Kortesniemi, M.; Liu, J.; Zhu, B.; Laaksonen, O. Sensory and chemical characterization of Chinese bog bilberry wines using Check-all-that-apply method and GC-Quadrupole-MS and GC-Orbitrap-MS analyses. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darıcı, M.; Cabaroglu, T. Chemical and sensory characterization of Kalecik Karası wines produced from two different regions in Turkey using chemometrics. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferremi Leali, N.; Salvetti, E.; Luzzini, G.; Salini, A.; Slaghenaufi, D.; Fusco, S.; Ugliano, M.; Torriani, S.; Binati, R.L. Differences in the Volatile Profile of Apple Cider Fermented with Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Fermentation 2024, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C. Comparison of aroma compounds in cabernet sauvignon red wines from five growing regions in Xinjiang in China. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 5562518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, D. Recent advances on aroma characteristics of compound fermented beverage: Analytical techniques, formation mechanisms and aroma-enhancement brewing technology. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidou, D.; Zotou, A.; Theodoridis, G. Wine and grape marc spirits metabolomics. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Pai, A.; Luo, J.; Gan, R.; Gao, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, P. Glycosidically bound aroma precursors in fruits: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.S.; Campos, F.; Cabrita, M.J.; Silva, M.G.D. Exploring the aroma profile of traditional sparkling wines: A review on yeast selection in second fermentation, aging, closures, and analytical strategies. Molecules 2025, 30, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarko, T.; Duda, A. Volatilomics of compound fermented beverages. Molecules 2024, 29, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Ji, M.; Gong, J.; Chitrakar, B. The formation of volatiles in compound fermented beverage process and its impact on wine quality. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szudera-Kończal, K.; Myszka, K.; Kubiak, P.; Majcher, M.A. Analysis of the ability to produce pleasant aromas on sour whey and buttermilk by-products by mold Galactomyces geotrichum: Identification of key odorants. Molecules 2021, 26, 6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Kathuria, D.; Barthwal, R.; Joshi, R. Metabolomics of chemical constituents as a tool for understanding the quality of fruits during development and processing operations. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 4169–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yu, K.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Xiao, X.; Xie, L.; Wei, Z.; Xiong, R.; Zhou, X. Effects of plant-derived polyphenols on the antioxidant activity and aroma of sulfur-dioxide-free red wine. Molecules 2023, 28, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Marie-Colette, A.K.; Liu, Q.; Hao, N.; Wang, J. Analyzing the contribution of functional microorganism to volatile flavor compounds in Semillon wine and predicting their metabolic roles during natural fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2025, 223, 117842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokumnoyporn, N.; Samakradhamrongthai, R.S. The Stability. In Aroma and Flavor in Product Development: Characterization, Perception, and Application; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Prusova, B.; Humaj, J.; Sochor, J.; Baron, M. Formation, losses, preservation and recovery of aroma compounds in the winemaking process. Fermentation 2022, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variety | Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Reducing Sugars (g/L) | Total Acidity (g/L) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Riesling | 25.11 ± 1.09 | 231.33 ± 9.82 | 6.09 ± 0.07 | 3.65 ± 0.21 |

| Sir Prize Apple | 14.31 ± 0.32 | 116.52 ± 0.51 | 7.78 ± 0.95 | 3.43 ± 0.02 |

| Grape juice–apple puree | 22.82 ± 0.21 | 218.01 ± 1.22 | 5.61 ± 0.14 | 3.62 ± 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Ma, J.; Chu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Jia, Y. Multi-Omics Elucidation of Flavor Characteristics in Compound Fermented Beverages Based on Flavoromics and Metabolomics. Foods 2025, 14, 4119. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234119

Li X, Ma J, Chu Y, Li H, Zhang Y, Li A, Jia Y. Multi-Omics Elucidation of Flavor Characteristics in Compound Fermented Beverages Based on Flavoromics and Metabolomics. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4119. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234119

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaolong, Jun Ma, Yannan Chu, Hui Li, Yin Zhang, Abo Li, and Yonghua Jia. 2025. "Multi-Omics Elucidation of Flavor Characteristics in Compound Fermented Beverages Based on Flavoromics and Metabolomics" Foods 14, no. 23: 4119. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234119

APA StyleLi, X., Ma, J., Chu, Y., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Li, A., & Jia, Y. (2025). Multi-Omics Elucidation of Flavor Characteristics in Compound Fermented Beverages Based on Flavoromics and Metabolomics. Foods, 14(23), 4119. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234119