Abstract

Coordination polymers, particularly those with one- and two-dimensional structures, have garnered significant attention owing to their excellent electrical and optical properties. However, the development of reliable molding techniques for fabricating thin films, pellets, and ingots remains critical for practical applications. In this study, we introduce a novel approach for the direct formation of continuous Ag-coordinated polymer thin films on polymer substrates doped with Ag ions. This process involves ion exchange between the doped Ag ions within the substrate and the protons of the organic ligands, followed by the formation of interfacial complexes between the eluted Ag ions and ligands. Time-resolved analysis revealed that ligand concentration plays a crucial role in thin film formation. Specifically, higher ligand concentrations accelerate nucleation, resulting in the formation of thin films composed of densely packed small-sized crystals. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method for fabricating high-density, uniformly coordinated polymer thin films.

1. Introduction

Coordination polymers (CPs) are composite materials comprising periodically arranged metal nodes (metal ions or clusters) and bridging organic ligands [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Among these, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have attracted significant attention because their crystalline micropores provide exceptionally high specific surface areas [1,2,3,4]. The microstructure and chemical properties of these materials can be precisely tailored by selecting the appropriate metal ions, organic ligands, and synthetic conditions, thereby enabling diverse applications such as gas storage and separation [8,9,10], catalysis [11,12,13], and drug delivery [14,15,16]. Despite their promising potential, most CPs, which are typically composed of multivalent metal ions and redox-inactive ligands, exhibit low intrinsic electrical conductivities, thereby restricting their use in electronic applications. However, the inherent design flexibility of CPs has inspired several strategies to enhance their conductivity, including through-bond, through-space, redox hopping, guest-promoted, and π−d conjugation mechanisms [17,18,19]. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated that CPs composed of metal ions and sulfur-containing organic ligands exhibit significantly higher conductivities than those based on oxygen- or nitrogen-containing organic ligands [20,21,22,23].

CPs are typically obtained as polycrystalline powders, which significantly limits their processability and practical use. To exploit their electrical properties in devices, such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes, field-effect transistors, sensors, and thermoelectric devices, it is essential to fabricate CP-based thin films on substrates. Several strategies have been developed for the fabrication of CP thin films and can be categorized into wet approaches, such as liquid–liquid interfacial reactions and layer-by-layer deposition, and dry approaches, such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [24,25,26,27]. CVD enables the formation of residue-free thin films with atomic-level uniformity and has become a widely employed approach in recent years owing to its solvent-free nature. However, dry approaches suffer from significant limitations, including restrictions on film size, process complexity, and high energy consumption associated with the required equipment. By contrast, most CP thin films reported in fundamental studies have been prepared employing wet methods. Nevertheless, these approaches present several challenges for device applications, such as the formation of nonuniform films owing to heterogeneous nucleation in solution, substrate corrosion caused by solvents, and surface tension effects at the solvent-substrate interface. Despite these issues, wet approaches have gained traction as environmentally friendly and straightforward fabrication methods, particularly with the recent development of printing techniques based on CP ink [28]. Therefore, to advance the wet approach toward practical device manufacturing, a detailed understanding of CP growth mechanisms both in solution and at reaction interfaces is essential.

Recently, we fabricated CP thin films via solid–liquid interface reactions utilizing metal ion-doped polymer films [29,30,31]. In this approach, metal ions are first adsorbed onto a polymer substrate, which is subsequently immersed in a ligand-containing solution, resulting in the growth of CP crystals on the substrate. This process is driven by an ion-exchange reaction between the adsorbed metal ions and protons of the ligand, thereby enabling the selective deposition of CP crystals. However, the nucleation and crystal growth mechanisms, particularly those involving complexation between metal ions and organic ligands, remain inadequately understood. Elucidating the growth mechanism of CP crystals at solid–liquid interfaces is critical, as it determines the size, shape, and crystallinity of the resulting CP crystals as well as microstructural features such as film thickness, intercrystal voids, and pinholes, which strongly influence the electrical properties of the resulting CP-based thin films. Therefore, elucidating these processes is essential for both the fundamental development of CP materials and their integration into device architectures.

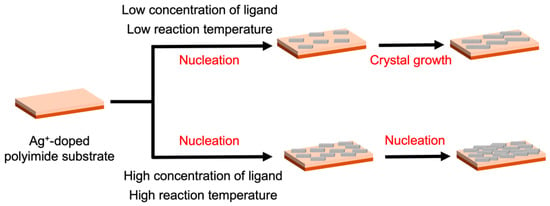

In this study, we prepared [Ag(tzdt)]n crystal-based thin films (denoted as KGF-24, where tzdt = 2-thiazoline-2-thiolate) at the interface between a Ag ion-doped polyimide film surface and a ligand-containing reaction solution, and analyzed the corresponding growth mechanism. KGF-24 crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c and forms a two-dimensional coordination polymer composed of a one-dimensional [–Ag–S–]n chain (Figure 1A), imparting distinctive semiconducting properties [32]. Although CPs such as KGF-24 are typically synthesized under hydrothermal conditions, we successfully fabricated KGF-24 thin films directly on substrates by applying the proposed solid–liquid interfacial CP formation technique utilizing metal ion-doped polymer films. Notably, we observed that the size of KGF-24 crystals can be tuned by adjusting the ligand concentration, which also strongly influences the degree of inter-crystalline gaps. Time-resolved analyses further revealed that an intermediate Ag–ligand phase was formed during the initial reaction stage, followed by a phase transition to KGF-24. At low ligand concentrations, fewer nuclei formed during this stage, whereas a high ligand concentration promoted the formation of more nuclei. These findings demonstrate that early-stage nucleation plays a crucial role in the production of thin films comprising densely packed crystals. This study not only elucidates the key aspects of CP crystal formation on substrates but also highlights a pathway for fabricating continuous CP thin films by controlling the nucleation and crystal growth processes.

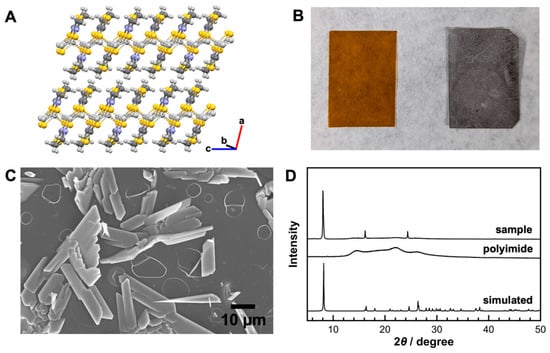

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the crystal structure of KGF-24, (B) optical images of the polymer film (left) before and (right) after the reaction, (C) SEM image of the obtained crystals, and (D) XRD patterns of the corresponding samples.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals

Potassium hydroxide and nitric acid were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan). Methanol and 2-thiazoline-2-thiol (Htzdt) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Japan Co., LLC (Tokyo, Japan). Silver trifluoroacetate was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Pyromellitic dianhydride oxidianiline (PMDA-ODA) type polyimide films (50 µm thick, Kapton 200H, TORAY KAPTON Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) were utilized as polymer substrates.

2.2. Preparation of KGF-24 Using Ag+-Doped Polymer Substrate

The polyimide films (1 × 2 cm2) were initially immersed in 5 M aqueous KOH solution at 50 °C for 5 min, followed by thorough rinsing with distilled water. The modified films were then immersed in a 100 mM methanol (CF3COO)Ag solution at 25 °C for 20 min. After rinsing with methanol, the ion-doped polymer films were transferred to a methanol solution containing Htzdt, followed by heating at 80 °C for 60 min under microwave irradiation. After heating, the reaction vessel was cooled to room temperature by blowing air from a compressor, and the resulting samples were then removed. The obtained samples were rinsed three times with methanol.

2.3. Characterization

The surface morphologies of the resulting films were examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JSM-7001FA, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were collected utilizing a diffractometer (RINT-2200 Ultima IV, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation. The number of Ag ions eluted from the substrate into the reaction solution was quantified employing inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP AES; SPS 7800, Seiko Instruments, Chiba, Japan). The chemical structure of the films was characterized by Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR; FT/IR-6300, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Ag+-Doped Polymer Substrate

To characterize changes in the chemical structure of the polyimide films after alkali treatment, FT-IR measurements were performed on the films (Figure S1). The bare polyimide film exhibits absorption bands assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the carbonyl groups coupled through the five-membered imide ring, appearing at 1780 and 1710 cm−1, respectively. The absorption band centered at 1500 cm−1 is attributed to the ring-breathing modes of the aromatic moieties in the ODA segment. In contrast, in the surface-modified film, the imide-related bands around 1700 cm−1 completely disappear, and new bands of amide are clearly visible at 1680 cm−1 (amide I; C=O stretching) and 1550 cm−1 (amide II; N-H bending and C-N stretching). These results indicate that the PMDA-ODA-type polyimide film underwent imide ring cleavage upon treatment with an aqueous solution of potassium hydroxide, yielding potassium carboxylate salts (ion-exchangeable sites) and amide bonds via conversion to poly(amic acid). Subsequently, the immersion of the modified polyimide film in a metal salt solution enabled the incorporation of metal ions into the film via ion exchange with potassium ions (Figure S2). In this study, for the first time, a methanolic solution of silver trifluoroacetate was employed as an ion-exchange medium rather than conventional aqueous metal salt solutions. The amount of silver ions incorporated into the film was quantified via ICP analysis. To quantify the concentration of adsorbed silver ions, the obtained film was immersed in 20 mL of 10% nitric acid solution to elute the bound silver ions. The number of adsorbed silver ions was nearly identical to that of the initially doped potassium ions in the film, confirming a one-to-one ion-exchange process between monovalent Ag+ and K+ ions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Amount of adsorbed metal ions in the polyimide film after KOH treatment and after ion-exchange utilizing (CF3COO)Ag/methanol solution.

3.2. Preparation of KGF-24 Crystal Films on Ag+-Doped Polymer Substrate

To form KGF-24 crystals on the substrate, the silver ion-doped film was immersed in a 10 mM methanol solution of the Htzdt ligand and heated under microwave irradiation at 80 °C for 60 min. The color of the film changed from brown (pristine polyimide) to white after the reaction, indicating crystal formation on the film surface (Figure 1B). The white crystals formed on the polyimide surface remained intact during the cooling and washing processes, suggesting relatively strong adhesion. SEM observations revealed that the morphology of the resulting crystals was consistent with that predicted for the space group of KGF-24 (Figure 1C). Thin rod-like crystals were formed on the substrate, exhibiting an average length (major axis) of approximately 10 µm, a width (minor axis) of approximately 3 µm, and a thickness of 0.3 µm. To gain insight into the distribution of silver ions in the obtained crystals, we performed energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis. The EDX mapping image revealed that the silver ions were uniformly distributed throughout the crystals (Figure S3). Furthermore, the XRD pattern of the sample aligned closely with the simulated pattern of the KGF-24 crystal (Figure 1D). The presence of sharp diffraction peaks confirmed the formation of highly crystalline KGF-24. Interestingly, analysis of the obtained diffraction pattern revealed that the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 8.2°, 16.3°, and 24.6° originate from the (100), (200), and (300) planes, respectively. SEM observation confirmed that the rod-like crystals lie horizontally on the substrate and exhibit a preferred orientation, resulting in an XRD pattern that displays reflections only from specific crystallographic planes. As expected, XRD measurement of the sample exfoliated from the substrate showed diffraction peaks from multiple planes, in agreement with the simulated pattern (Figure S4). However, under these conditions, the crystals were sparsely distributed, and substantial areas of the substrate surface remained exposed.

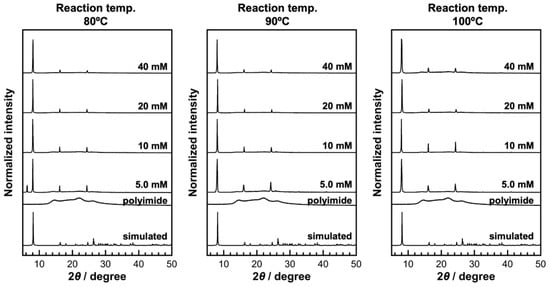

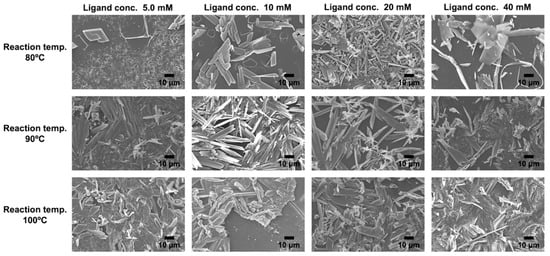

3.3. Effect of Concentration of Organic Ligand and Reaction Temperature

The crystallization behavior of CPs strongly depends on the ligand concentration and reaction temperature. Therefore, in this study, the reaction time was fixed at 60 min, and the effects of ligand concentration and reaction temperature on the surface morphology of the resulting samples were systematically examined (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Under reaction temperature at 80 °C and a ligand concentration of 5 mM, XRD measurement of the obtained sample displayed peaks corresponding to KGF-24, in conjunction with an additional unidentified peak near 2θ = 6.4° (Figure 2). SEM observations of the sample revealed large crystals with long axes exceeding 5 µm and numerous thin plate-like crystals formed on the substrate (Figure 3). Under these conditions, the low ligand concentration resulted in a slow reaction rate and incomplete consumption of the doped silver ions within the reaction time. This indicates that crystals of an unknown phase were formed during cooling after the reaction. At ligand concentrations exceeding 10 mM, both XRD measurements and SEM observations confirmed the exclusive formation of KGF-24 crystals on the substrate. As the ligand concentration increased, the number of crystals increased; at 20 mM, dense KGF-24 crystals were formed on the substrate. Although the major axis length of the crystals remained nearly constant, the minor axis and the thickness decreased to approximately 1.5 µm and 0.1 µm, respectively. These findings indicate that KGF-24 formation on the film can be initiated by an ion-exchange reaction between the doped silver ions and protons of the Htzdt ligands. Furthermore, increasing the Htzdt concentration accelerated ion exchange, thereby promoting rapid nucleation.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of KGF-24 crystals prepared at different reaction temperatures utilizing reaction solutions containing different concentrations of organic ligand.

Figure 3.

SEM images of KGF-24 crystals prepared at different reaction temperatures utilizing reaction solutions containing different concentrations of organic ligand.

Subsequently, the effect of reaction temperature on the crystallization process was investigated. As a preliminary test, the reaction was performed at 120 °C to define the applicable temperature range. The XRD analysis revealed no diffraction peaks attributable to the target KGF-24 phase; instead, an intense and sharp peak was observed at 2θ = 38° corresponding to metallic Ag, indicating that Ag+ ions were reduced in the methanol solvent under high-temperature conditions. These results clearly demonstrate that reaction temperatures exceeding 120 °C favor the reduction of silver ions rather than the formation of KGF-24 crystals. Therefore, subsequent evaluations of the crystal formation process were conducted within the temperature range of 80–100 °C. At higher temperature (above 90 °C) and low ligand concentration (5 mM), numerous crystals formed densely on the substrate, in contrast to the sparse crystal-based film observed at 80 °C. As the temperature increased, the length of the crystal axis decreased. To further elucidate the growth process more precisely, the ligand concentration in the reaction solution was systematically varied under high-temperature conditions (90 and 100 °C). The XRD patterns of the obtained samples exhibited only diffraction peaks corresponding to KGF-24 across the investigated ligand concentration range of 5–40 mM (Figure 2). The absence of broad peaks originating from the polyimide substrate indicated the formation of numerous KGF-24 crystals exhibiting high crystallinity. As described above, silver ion leaching from the film occurs via ion exchange with the protons of the organic ligands; therefore, the ligand concentration significantly influences both the number and size of the resulting KGF-24 crystals. As expected, increasing the ligand concentration (5.0–20 mM) yielded denser crystalline films characterized by reduced short-axis length and thickness in conjunction with elongation along the long-axis (Figure 3). For instance, at 100 °C and 5.0 mM ligand concentration, KGF-24 crystals with dimensions of approximately 8 µm (long axis), 5 µm (short axis), and 0.3 µm (thickness) were obtained, whereas at 20 mM, the crystals exhibited dimensions of approximately 20 µm (long axis), 3 µm (short axis), and 0.3 µm (thickness). In general, higher reaction temperatures promote thermodynamically favorable equilibrium states for complex formation, thereby favoring crystal growth over nucleation. However, the present results deviate from this trend, indicating that, even at high temperatures, the nucleation rate exceeds the crystal growth rate. This can be attributed to the rapid coordination kinetics between the soft d10 metal ions and chalcogenate ligands, wherein complexation proceeds nearly instantaneously upon collision. Consequently, numerous nuclei are formed before sufficient diffusion or reorganization can occur to sustain crystal growth, resulting in kinetically controlled crystallization. Under these high-temperature conditions, increasing the ligand concentration further accelerated ion exchange between the adsorbed metal ions and ligand protons, generating a greater number of crystals and an even higher nucleation rate. Notably, analysis of the crystal morphology revealed that although the long-axis dimension increased as ligand concentration increased, both the short axis and thickness decreased. These results suggest that the ligand concentration and reaction temperature primarily influence not the elongation of the [–Ag–S–]n network, but rather the formation and stacking of the two-dimensional layers derived from the [–Ag–S–]n network. Therefore, small two-dimensional layers likely form at the initial stage of the reaction, followed by elongation of the [–Ag–S–]n network to produce the final KGF-24 structure.

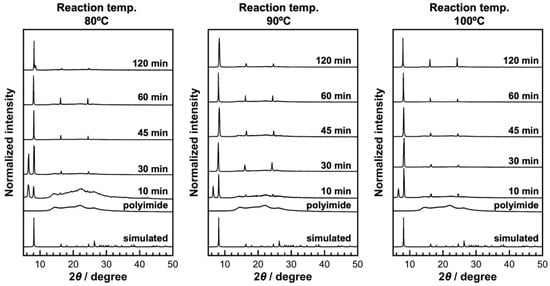

3.4. Time-Resolved Analysis of Nucleation and Growth of KGF-24 Crystals

To elucidate the nucleation and growth behavior of KGF-24 crystals, time-dependent SEM and XRD analyses were conducted at 80 °C and a ligand concentration of 10 mM. In the initial reaction stage (10 min), thin plate-like crystals of KGF-24 were observed, in conjunction with numerous plate-like structures distinct from those of KGF-24 (Figure 4). The corresponding XRD pattern exhibited diffraction peaks attributable to KGF-24 in conjunction with a broad, unidentified peak near 2θ = 6.4° as well as a halo pattern from the polyimide substrate, consistent with the SEM observations (Figure 5). At higher reaction temperatures, diffraction peaks from the unidentified phase were still detected; however, these were weaker in intensity. By contrast, the SEM images indicated that plate crystals based on crystals with unidentified phases were sparsely formed on the substrate. These results indicate that the formation of the KGF-24 phase was thermally promoted. For comparison, in the synthesis of [Au(SPh)]n CP comprising Au+ and thiophenolate ligands, crystal formation proceeds via an amorphous intermediate that subsequently transforms to a crystalline phase [33]. A similar transformation from a kinetically stable intermediate to a thermodynamically stable crystalline phase is likely to occur in this system. Indeed, as the reaction progressed, the unidentified XRD peak completely disappeared after 45 min at 80 °C and after 30 min at 90 °C and 100 °C, leaving only reflections attributable to KGF-24, consistent with a phase transition. SEM analysis of the 30 min sample revealed a mixture of extremely small and relatively large crystals, indicating that nucleation and growth occurred concurrently rather than sequentially. As the reaction time increased, the number of crystals became nearly constant, suggesting that nucleation was completed within the initial stage of the reaction within 30 min. During this period, the short-axis length and thickness increased marginally, whereas the long-axis dimensions increased significantly. By contrast, samples prepared at 100 °C exhibited no significant changes in crystal size. Detailed surface observations indicated that dense crystals were already formed after 30 min, with substrate exposure gradually decreasing as the reaction proceeded. After 2 h, the crystals were completely packed, implying that the intercrystalline spaces were limited during the early stages of the reaction. Spatial confinement during the reaction likely impeded crystal growth, resulting in sustained nucleation. The observed crystal thickness aligned closely with the overall film thickness, indicating the formation of a CP-based thin film composed of a single crystalline layer.

Figure 4.

Time-resolved analysis of surface morphology of the obtained samples prepared at different reaction temperatures.

Figure 5.

Time-resolved analysis of crystal structure of the obtained samples prepared at different reaction temperatures.

The observed dependence of nucleation and growth behavior on the ligand concentration and reaction temperature indicates that the dissolution of adsorbed metal ions is the rate-determining step in crystal formation, as complexation between metal ions and organic ligands proceeds extremely rapidly. Consequently, the dissolution rate of metal ions critically governs the surface morphology, that is, the size, shape, and density of the KGF-24 crystals on the substrate. Based on these findings, a formation mechanism for KGF-24 thin films is proposed (Figure 6): during the initial reaction stage, short-chain [–Ag–S–]n structures form, followed by the assembly of two-dimensional layers derived from these chains and subsequent stacking of the layers. At higher ligand concentrations and reaction temperatures, the accelerated dissolution of the doped metal ions promotes rapid nucleation, yielding densely packed KGF-24 thin films with minimal intergranular voids.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the proposed mechanism for the formation of KGF-24 crystals via the proposed ion-exchange-driven growth process.

4. Conclusions

This study elucidated the formation mechanism of the coordination polymer thin film KGF-24 by systematically correlating the ligand concentration, reaction temperature, and reaction time with nucleation and growth behavior. The results demonstrated that film formation proceeded via ion-exchange-induced dissolution of silver ions from the polymer substrate, followed by rapid complexation with the chalcogenide ligand to yield [–Ag–S–]n chains and subsequent layer stacking. Higher ligand concentrations and temperatures accelerated metal ion release and complexation, promoting dense nucleation and the formation of compact crystalline films. These findings provide mechanistic insights into the ion-exchange-driven growth of CP thin films and offer a guiding principle for controlling their crystallinity and morphology via kinetic modulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13120396/s1, Figure S1. FT-IR spectra for polyimide films before and after KOH treatment. Figure S2. Schematic illustration of the formation of KGF-24 CPs on the polymer substrate. Figure S3. (A) SEM image and (B) EDX mapping of Ag element of the obtained sample. Figure S4. XRD pattern of KGF-24 crystals exfoliated from the substrate.

Author Contributions

R.O. and T.T. performed the synthesis experiments and the characterization. T.T. conceived the experiments and supervised project. T.T., Y.T. and K.A. analyzed all data and discussed the formation mechanism of KGF-24 crystals on the substrate. T.T. contributed to and managed all aspects of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23K04897 and Konan Advanced Research Project (Phase 1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Framework. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, S.; Kitaura, R.; Noro, S. Functional Porous Coordination Polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2334–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férey, G.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Serre, C.; Millange, F. Crystallized Frameworks with Giant Pores: Are There Limits to the Possible? Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptopoulou, C.P. Metal-Organic Frameworks: Synthetic Methods and Potential Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, B.; Zaworotko, M.J. From Molecules to Crystal Engineering: Supramolecular Isomerism and Polymorphism in Network Solids. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1629–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiak, C. Engineering coordination polymers towards applications. Dalton Trans. 2003, 2781–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.L.; Vittal, J.J. One-Dimensional Coordination Polymers: Complexity and Diversity in Structures, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 688–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglar, H.; Gulbalkan, H.C.; Avci, G.; Aksu, G.O.; Altundal, O.F.; Altintas, C.; Erucar, I.; Keskin, S. Effect of Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) Database Selection on the Assessment of Gas Storage and Separation Potentials of MOFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7828–7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Wen, H.-M.; Gu, X.-W.; Qian, Q.-L.; Yang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, B.; Qian, G. Dense Packing of Acetylene in a Stable and Low-Cost Metal–Organic Framework for Efficient C2H2/CO2 Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25068–25074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Rimoldi, M.; Howarth, A.J.; Chen, H.; Alayoglu, S.; Snurr, R.Q.; Farha, O.K.; Hupp, J.T. Ammonia Capture within Zirconium Metal–Organic Frameworks: Reversible and Irreversible Uptake. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 20081–20093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jial, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.-L. Microenvironment Modulation in Metal–Organic Framework-Based Catalysis. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021, 2, 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-B.; Si, D.-H.; Wu, Q.-J.; Weng, Z.; Cao, R. Porous Metal–Organic Framework Liquids for Enhanced CO2Adsorption and Catalytic Conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 20915–20920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, A.; Nejatbakhsh, S.; Soodmand, A.M.; Farshchi, M.E.; Aghdasinia, H. High-performance catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol to 4-aminophenol using M-BDC (M = Ag, Co, Cr, Mn, and Zr) metal–organic frameworks. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, I.A.; Wells, C.J.R.; Forgan, R.S. Multivariate Modulation of the Zr MOF UiO-66 for Defect-Controlled Combination Anticancer Drug Delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5211–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, S.; Hemmati, A.; Namazi, H.; Heydari, A. Carboxymethylcellulose-coated 5-fluorouracil@MOF-5 nano-hybrid as a bio-nanocomposite carrier for the anticancer oral delivery. Int. J. Bio. Macromole. 2020, 155, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.S.; Dode, T.; Kawashima, S.; Fukuoka, M.; Tsuruoka, T.; Nagahama, K. Metal–organic framework-injectable hydrogel hybrid scaffolds promote accelerated angiogenesis for in vivo tissue engineering. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 32143–32154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.S.; Skorupskii, G.; Dincă, M. Electrically Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8536–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Dutta, B.; Paul, R.; Mir, M.H. Charge transport and device fabrication of 2D coordination polymeric materials. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 13401–13420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liu, D.; Xu, H.; Dong, H.; Hu, W. Electrically Conductive Coordination Polymers for Electronic and Optoelectronic Device Applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henfling, S.; Kempt, R.; Klose, J.; Kuc, A.; Kersting, B.; Krautscheid, H. Dithiol–Dithione Tautomerism of 2,3-Pyrazinedithiol in the Synthesis of Copper and Silver Coordination Compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 16441–16453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W. Highly Conductive Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Silver Sulfide with 3D Silver–Sulfur Networks Constructed from Benzenehexathiol: Structural Topology Regulation via Ligand Oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 5060–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, K.; Chen, T.; Gormley, E.L.; Hendon, C.H.; Dincă, M.; Brozek, C.K. Electrically conductive [Fe4S4]-based organometallic polymers. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11410–11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veselska, O.; Demessence, A. d10 coinage metal organic chalcogenolates: From oligomers to coordination polymers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 355, 240–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Giménez, V.; Arnauts, G.; Wang, M.; Mata, E.S.O.; Huang, X.; Lan, T.; Tietze, M.L.; Kravchenko, D.E.; Smets, J.; Wauteraerts, N.; et al. Chemical Vapor Deposition and High-Resolution Patterning of a Highly Conductive Two-Dimensional Coordination Polymer Film. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, C.; Chang, Z.; Wu, S.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xu, W. Synthesis of a highly conductive coordination polymer film via a vapor–solid phase chemical conversion process. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 8720–8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Un, H.-I.; Liu, T.-J.; Liang, B.; Polozij, M.; Hambsch, M.; Pöhls, J.F.; Weitz, R.T.; Mannsfeld, S.C.B.; Kaiser, U.; et al. A Low-Synmmetry Copper Benzenhexathiol Coordination Polymer with In-Plane Electrical Anisotropy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202423341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fu, S.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tadayon, K.; Hambsch, M.; Pohl, D.; Yang, Y.; Müller, A.; Zhao, F.; et al. Ammonia-Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of Two-Dimensional Conjugated Coordination Polymer Thin Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 18190–18196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, P.M.; Lien, C.-Y.; de Jong, L.O.; Spellberg, J.L.; Czaikowski, M.E.; Wang, L.; Filatov, A.S.; King, S.B.; Anderson, J.S. Processable Coordination Polymer Inks for Highly Conductive and Robust Coatings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 33608–33615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruoka, T.; Kumano, M.; Mantani, K.; Matsuyama, T.; Miyanaga, A.; Ohhashi, T.; Takashima, Y.; Minami, H.; Suzuki, T.; Imagawa, K.; et al. Interfacial Synthetic Approach for Constructing Metal-Organic Framework Crystals Using Metal Ion-Doped Polymer Substrate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 2472–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruoka, T.; Mantani, K.; Miyanaga, A.; Matsuyama, T.; Ohhashi, T.; Takashima, Y.; Akamatsu, K. Morphology Control of Metal-Organic Frameworks Based on Paddle-Wheel Units on Ion-Doped Polymer Substrate Using An Interfacial Growth Approach. Langmuir 2016, 32, 6068–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohhashi, T.; Tsuruoka, T.; Fujimoto, S.; Takashima, Y.; Akamatsu, K. Controlling the Orientation of Metal-Organic Framework Crystals by an Interfacial Growth Approach Using a Metal Ion-Doped Polymer Substrate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyoshi, R.; Saeki, A.; Ogasawara, K.; Yoshikawa, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Tanaka, D. Selective synthesis of two-dimensional semiconductive coordination polymers with silver–sulfur network. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 2990–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruoka, T.; Ohhashi, T.; Watanabe, J.; Yamada, R.; Hirao, S.; Takashima, Y.; Demessence, A.; Vaidya, S.; Veselska, O.; Fateeva, A.; et al. Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly on Polymer Surface for Efficient Synthesis of [Au(SPh)]n Coordination Polymer-Based Films. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 1961–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).