A Context-Aware Representation-Learning-Based Model for Detecting Human-Written and AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets Across Large Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

Motivation and Research Objectives

- To construct a balanced, domain-specific dataset comprising real and AI-generated cryptocurrency tweets regenerated using multiple LLMs;

- To propose a model to identify which LLM model was used to generate the AI-generated cryptocurrency text;

- To contribute to enhancing AI transparency and trust in financial communication by offering a robust detection model.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of Large Language Models

2.2. Applications and Comparative Studies

2.3. Detection of AI-Generated Text

2.4. Research Gap and Contributions

- Novel Dataset Preparation: We prepared a novel finance-based dataset using LLaMA3.2, Phi3.5, Gemma2, Qwen2.5, Mistral, and LLaVA.

- Dataset Pre-Processing: This study considered different efficient pre-processing steps for dataset cleaning, making it applicable to ML and DL models and preserving the contextual meaning.

- Fine-Tuning of Transformer Models: We extensively fine-tuned the transformer models to achieve an effective score and run the models with limited resources.

- Transformer Model Comparison: The proposed fine-tuned DeBERTa base model was compared with other models, such as DistilBERT, BERT base, ELECTRA, and ALBERT base V1.

- Machine Learning Models: Different machine learning models, such as logistic regression, naive Bayes, random forest, decision trees, XGBoost, AdaBoost, and voting (AdaBoost, GradientBoosting, XGBoost), with a word2vec approach, were applied to the prepared dataset to prove the proposed model’s robustness.

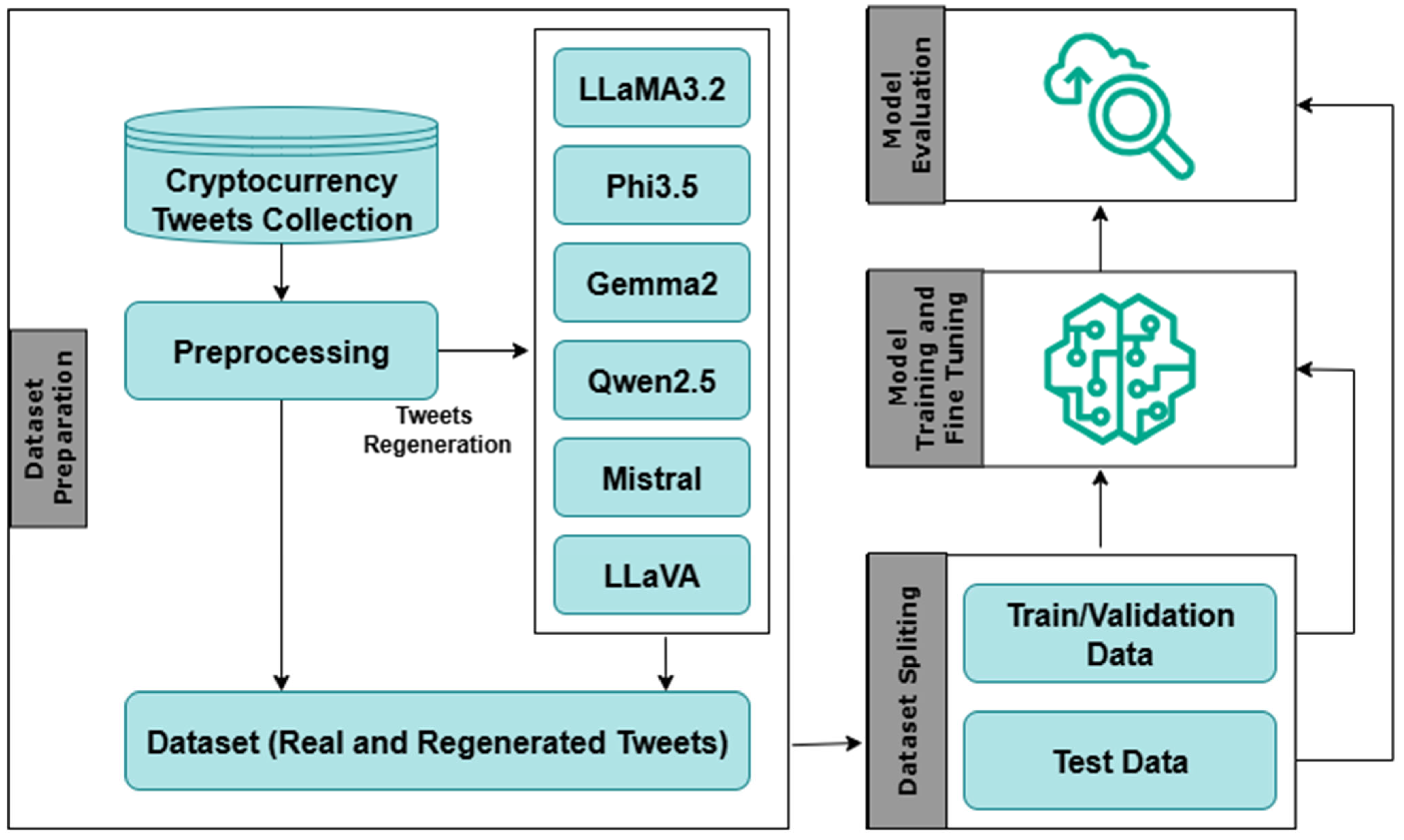

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Dataset and AI Tweet Generation

- Real Cryptocurrency Tweets: Only 25,000 actual tweets were retrieved from the open-source “Cryptocurrency Tweets” dataset, available on Kaggle [42]. These tweets represent genuine user expression related to crypto markets, news, and community discussions.

- AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets using LLMs: We utilized local LLMs to run via Ollama [43] to regenerate the cryptocurrency text to prepare the final dataset. The selected models included LLaMA3.2:3B, Phi3.5:8b, Gemma2:9B, Qwen2.5:7B, Mistral:7B, and LLaVa:7B. Each LLM was trained on original human tweets to generate domain-consistent, semantically rich, and sentimentally diverse content. The inclusion of multiple LLMs was essential to ensure cross-model diversity and generalization. Since different LLMs produce content with distinct stylistic and contextual signatures, their outputs collectively simulate a realistic and challenging detection environment for the proposed model.

- Dataset Composition: To reduce overfitting and overcome the issues with the majority and minority classes, we considered a balanced dataset. The final prepared dataset consisted of ~175,000 data samples with ~25,000 samples per class before pre-processing. The dataset can easily be extended to incorporate newly emerging LLMs by regenerating the original content corpus using any additional model. This ensures that the detection framework remains future-ready and adaptable.

3.2. Pre-Processing

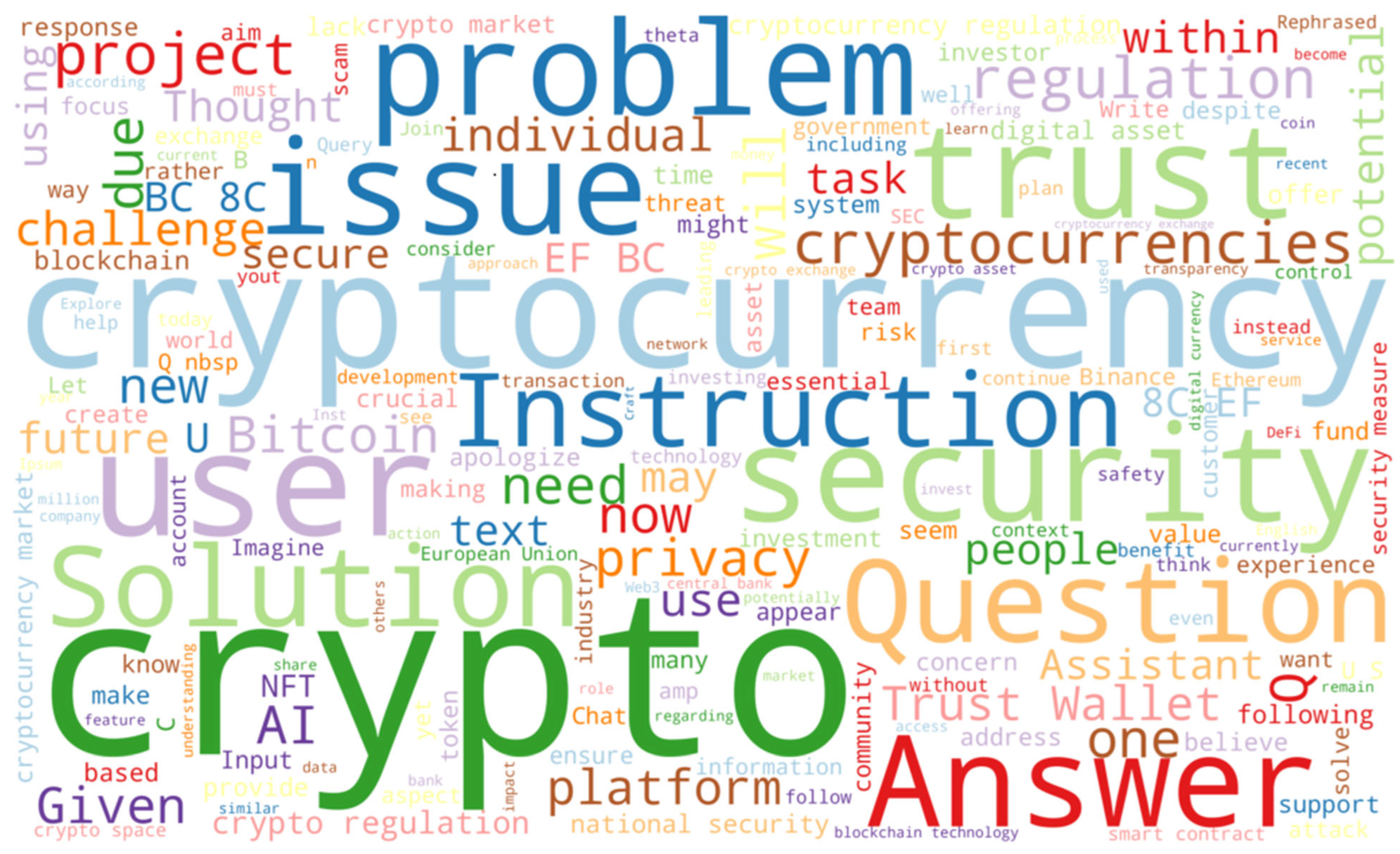

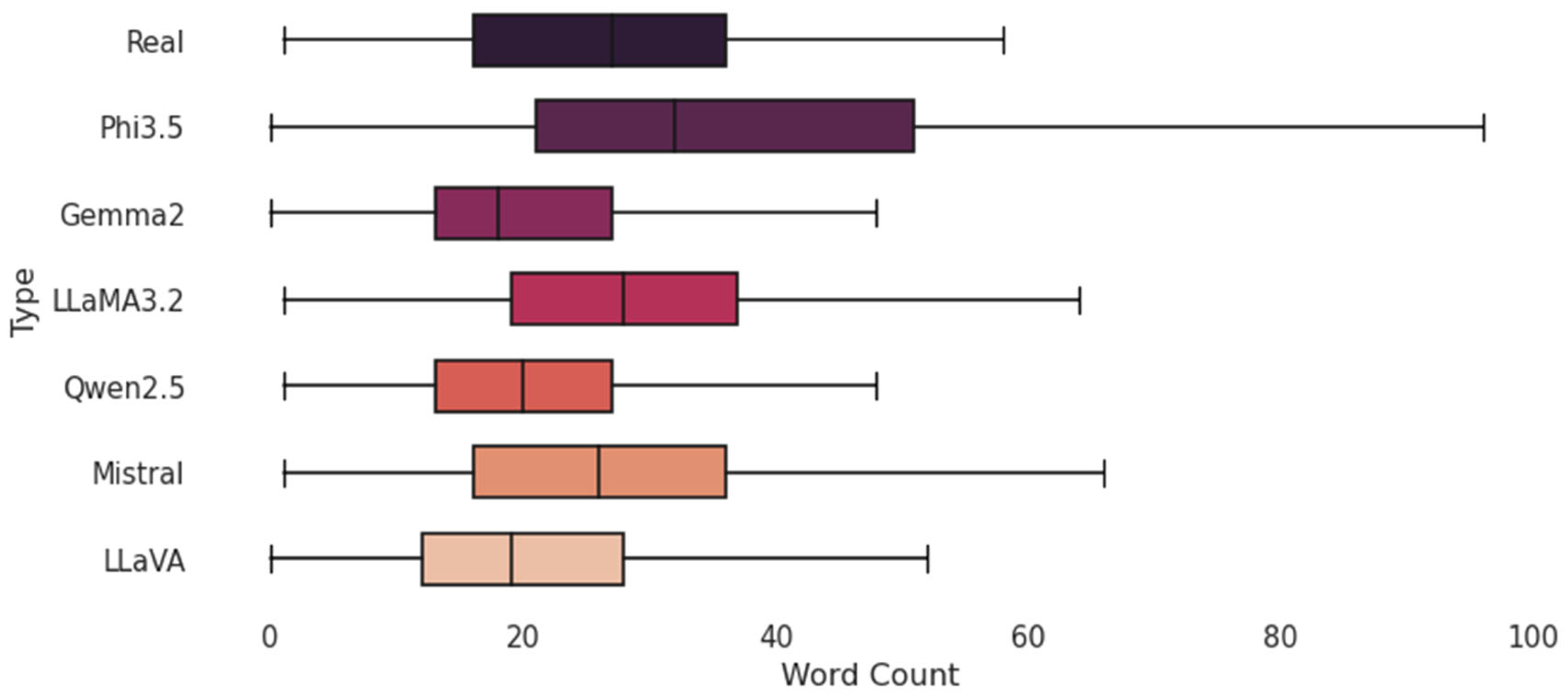

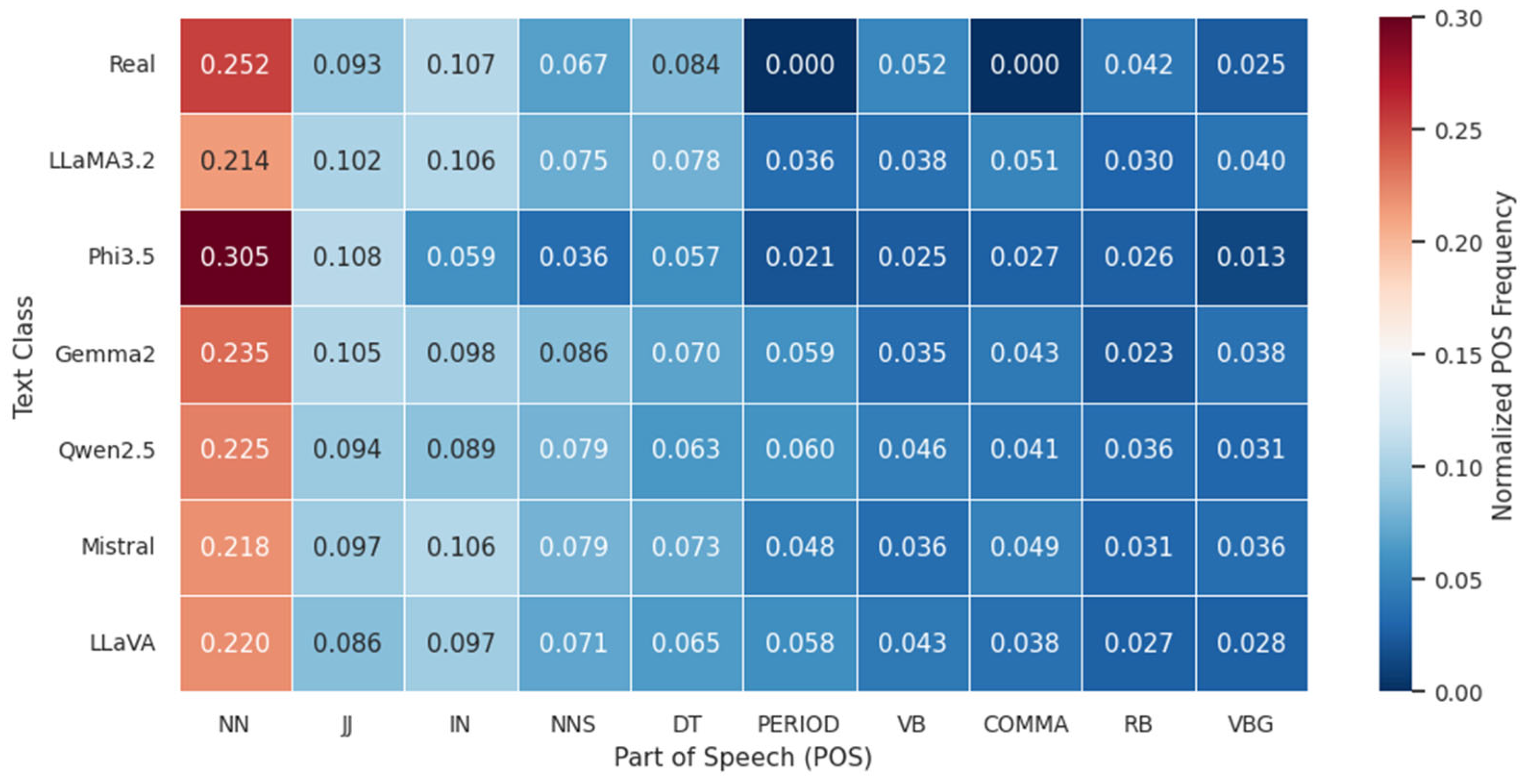

3.3. Linguistic Analysis

3.4. Proposed Model (Fine-Tuned)

- Disentangled Attention Mechanism: This concept separates the word content and position to capture the more complex relationship between words.

- Enhanced Mask Decoder: This enhanced the pre-training objective to make the model more operative in downstream tasks.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Experimental and Hardware Setup

4.3. Hyperparameter Configurations

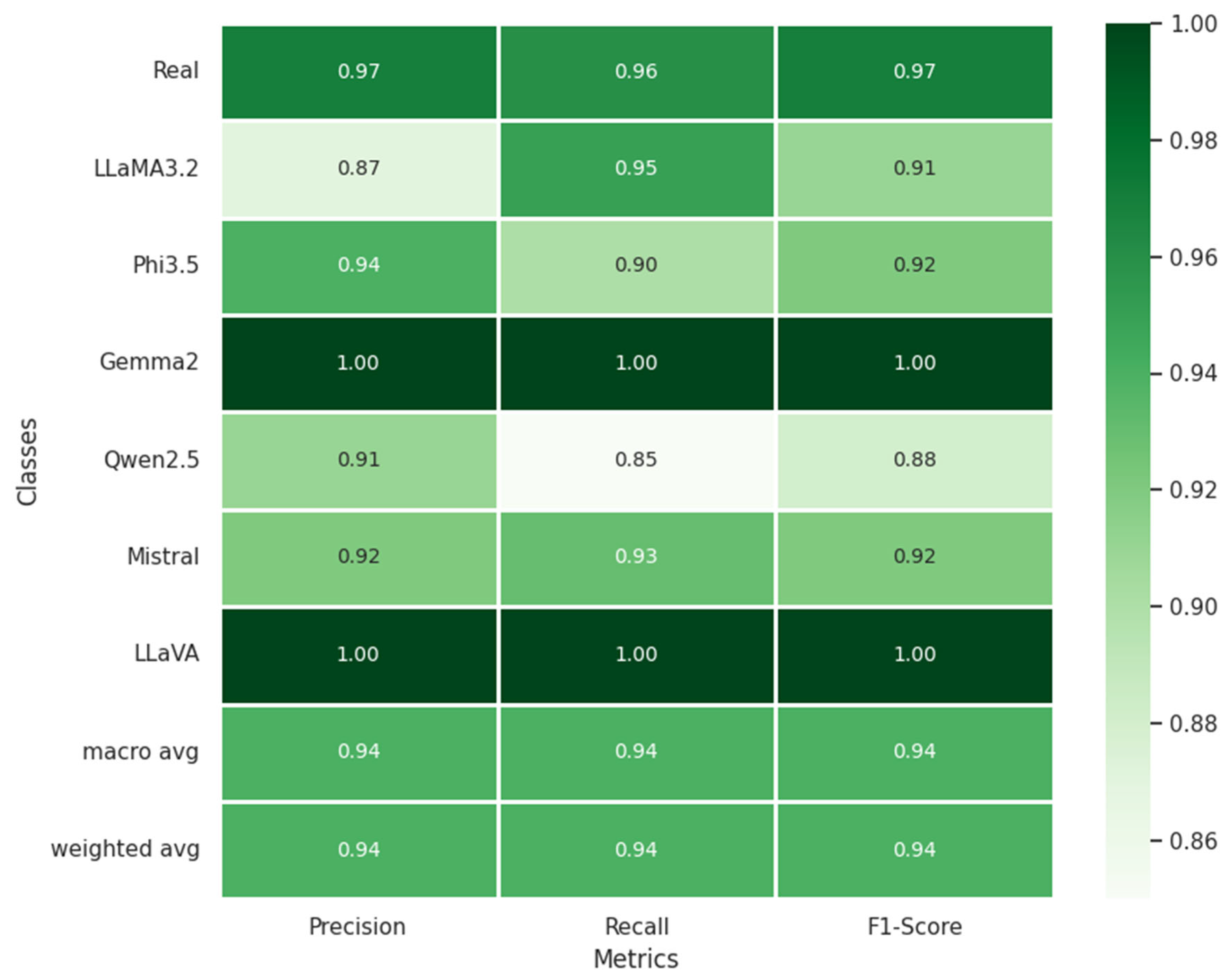

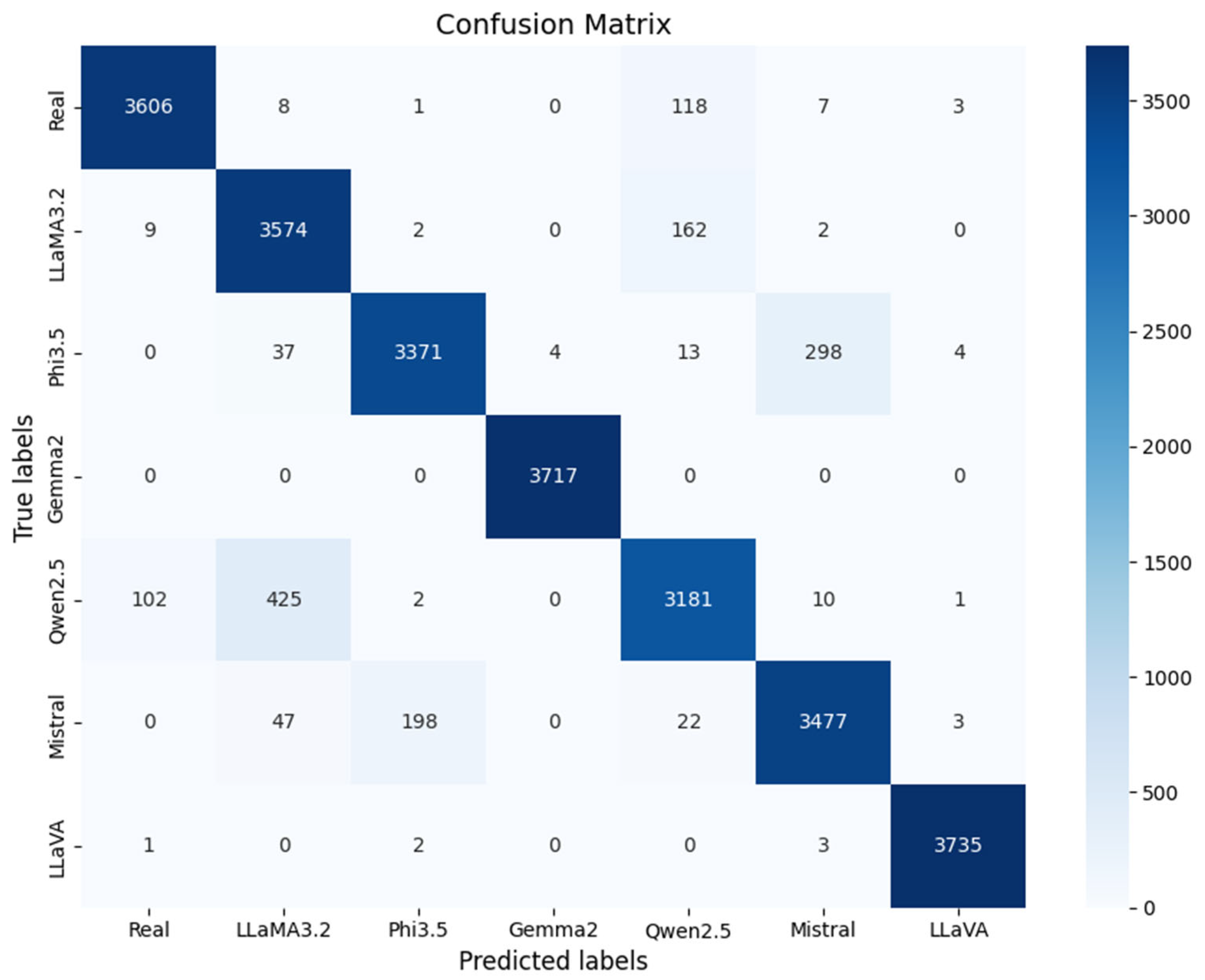

4.4. Proposed Model Results

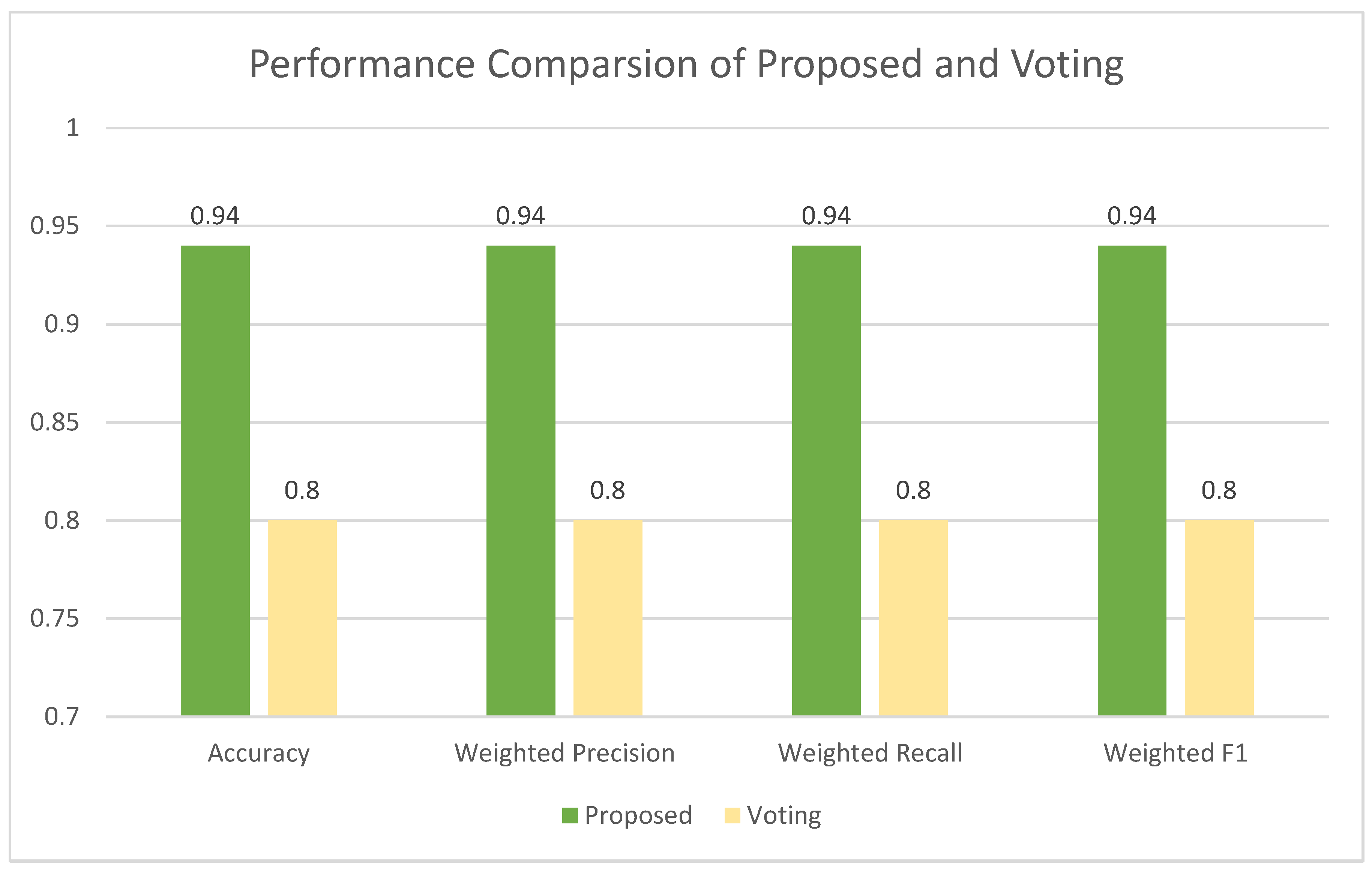

4.5. Performance of the Machine Learning (ML) Models over the Prepared Dataset

4.6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2025, 16, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Han, Q.-L.; Tang, Y. A Brief Overview of ChatGPT: The History, Status Quo and Potential Future Development. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrini, A.; Khamoshifar, M.; Abbasimehr, H.; Riggs, R.J.; Esmaeili, M.; Majdabadkohne, R.M.; Pasehvar, M. ChatGPT: Applications, Opportunities, and Threats. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium, SIEDS 2023, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 27–28 April 2023; pp. 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, P.; Kaur, M.; Thomas, A. E-Tailers’ Twitter (X) Communication: A Textual Analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2025, 49, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Shao, Y. The Impact of News Media Sentiment on Financial Markets. SSRN Electron. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.-A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.; Aggarwal, P.; Murahari, V.; Rajpurohit, T.; Kalyan, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Deshpande, A.; da Silva, B.C. RLHF Deciphered: A Critical Analysis of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback for LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08555v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta Llama 2. Available online: https://www.llama.com/llama2/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Awadalla, H.; Awadallah, A.; Awan, A.A.; Bach, N.; Bahree, A.; Bakhtiari, A.; Bao, J.; Behl, H.; et al. Phi-3 Technical Report: A Highly Capable Language Model Locally on Your Phone. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.14219v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qwen Team. Qwen2.5 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15115v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma Team. Gemma 2: Improving Open Language Models at a Practical Size. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2023, 36, 34892–34916. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2304.08485 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Verma, A.A.; Kurupudi, D.; Sathyalakshmi, S. BlogGen-A Blog Generation Application Using Llama-2. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems, ADICS 2024, Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malisetty, B.; Perez, A.J. Evaluating Quantized Llama 2 Models for IoT Privacy Policy Language Generation. Future Internet 2024, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.-T. Summarization Branches Out and Undefined 2004 Rouge: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/W04-1013.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating Text Generation with Bert. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Short text classification based on Wikipedia and Word2vec. In Proceedings of the 2016 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 14–17 October 2016; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7924894/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/D14-1162.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Labruna, T.; Fondazione, S.B.; Kessler, B.; Fondazione, B.M. Dynamic Task-Oriented Dialogue: A Comparative Study of Llama-2 and Bert in Slot Value Generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Student Research Workshop, St. Julian’s, Malta, 21–22 March 2024; pp. 358–368. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2024.eacl-srw.29/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ye, F.; Manotumruksa, J.; Yilmaz, E. MultiWOZ 2.4: A Multi-Domain Task-Oriented Dialogue Dataset with Essential Annotation Corrections to Improve State Tracking Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, Edinburgh, UK, 7–9 September 2022; pp. 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Lian, Q. Benchmarking of Commercial Large Language Models: ChatGPT, Mistral, and Llama. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Hayawi, K. Let’s have a chat! A Conversation with ChatGPT: Technology, Applications, and Limitations. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2023, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshed, M.A.; Gherghina, Ș.C.; Dewi, C.; Iqbal, A.; Mumtaz, S. Unveiling AI-Generated Financial Text: A Computational Approach Using Natural Language Processing and Generative Artificial Intelligence. Computation 2024, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P. An era of ChatGPT as a significant futuristic support tool: A study on features, abilities, and challenges. BenchCouncil Trans. Benchmarks Stand. Eval. 2022, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penelitian, J.; Pembelajaran, P.; Nurmayanti, N.; Stkip, S.; Banten, S. The Effectiveness of Using Quillbot in Improving Writing for Students of English Education Study Program. J. Teknol. Pendidikan J. Penelit. Dan Pengemb. Pembelajaran 2023, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenstrakh, M.S.; Karnalim, O.; Suarez, C.A.; Liut, M. Detecting LLM-Generated Text in Computing Education: A Comparative Study for ChatGPT Cases. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Osaka, Japan, 2–4 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Song, D. A Survey of Controllable Text Generation Using Transformer-based Pre-trained Language Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarage, T.; Garland, J.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Trapeznikov, K.; Ruston, S.; Liu, H. Stylometric Detection of AI-Generated Text in Twitter Timelines. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.03697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshy, A.; Sundar, S. Analyzing the Performance of Sentiment Analysis using BERT, DistilBERT, and RoBERTa. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Power and Renewable Energy Conference, IPRECON 2022, Kollam, India, 16–18 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Májovský, M.; Černý, M.; Kasal, M.; Komarc, M.; Netuka, D. Artificial Intelligence Can Generate Fraudulent but Authentic-Looking Scientific Medical Articles: Pandora’s Box Has Been Opened. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e46924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.; Vavekanand, R. Llama 3.1: An In-Depth Analysis of the Next-Generation Large Language Model. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatat, A.M.; Elsaid, K.; Almeer, S. Evaluating the efficacy of AI content detection tools in differentiating between human and AI-generated text. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2023, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A. Improving detection of chatgpt-generated fake science using real publication text: Introducing xfakebibs a supervised-learning network algorithm. Preprints 2023. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202304.0350 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Alamleh, H.; AlQahtani, A.A.S.; ElSaid, A. Distinguishing Human-Written and ChatGPT-Generated Text Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 27–28 April 2023; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10137767 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Perkins, M. Academic Integrity considerations of AI Large Language Models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pr. 2023, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranty, D.; Widiati, U. An automated writing evaluation (AWE) in higher education. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 2021, 11, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abburi, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bowen, E.; Pudota, N. AI-generated Text Detection: A Multifaceted Approach to Binary and Multiclass Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11550v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, G.; Mohammad, N.; Brahim, G.B.; Alghazo, J.; Fawagreh, K. Detection of AI-written and human-written text using deep recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the Fourth Symposium on Pattern Recognition and Applications (SPRA 2023), Napoli, Italy, 1–3 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryptocurrency Tweets. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/infsceps/cryptocurrency-tweets/data (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ollama. Available online: https://ollama.com/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Siino, M.; Tinnirello, I.; La Cascia, M. Is text preprocessing still worth the time? A comparative survey on the influence of popular preprocessing methods on Transformers and traditional classifiers. Inf. Syst. 2024, 121, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyajiwala, A.; Ladkat, A.; Jagadale, S.; Joshi, R. On Sensitivity of Deep Learning Based Text Classification Algorithms to Practical Input Perturbations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2201.00318. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Merchan, E.C.; Gozalo-Brizuela, R.; Gonzalez-Carvajal, S. Comparing BERT against traditional machine learning text classification. J. Comput. Cogn. Eng. 2020, 2, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, B. Contextual Language Understanding Thoughts on Machine Learning in Natural Language Processing. 2019. Available online: https://amu.hal.science/tel-02470185 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Zhou, M.; Duan, N.; Liu, S.; Shum, H.Y. Progress in Neural NLP: Modeling, Learning, and Reasoning. Engineering 2020, 6, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 4–6 October 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. DeBERTa: Decoding-enhanced BERT with Disentangled Attention. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2021-9th International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, G.; Zuva, T.; Sibanda, E.M. A Review of Evaluation Metrics in Machine Learning Algorithms. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2023, 724, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, D.E.; Patasik, I. Performance comparison of tf-idf and word2vec models for emotion text classification. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2021, 10, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Domain/Dataset | Approach/Model | Accuracy/Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arshed et al. [26] | Financial tweets | Word2Vec + random forest | Accuracy of 0.74; highlight difficulty in distinguishing AI-generated tweets |

| Kumarage et al. [31] | Twitter (general stylometric) | Roberta-based classifier | Successfully detected AI vs. human tweets using linguistic and stylistic cues |

| Elkhatat et al. [35] | General text (GPT3.5, GPT4, human) | Comparative tool analysis (GPTZero, Copyleaks, CrossPlag) | Found inconsistencies in existing AI detection tools |

| Hamed [36] | General text | ML ensemble | Proposed reliable ML algorithm for human and AI text discrimination |

| Alamleh et al. [37] | Academic and general text | SVM, RF, DT, NN | Found random forest to be the most effective |

| Abburi et al. [40] | Mixed domain | Neural hybrid | Achieved a good accuracy for binary and multiclass AI text detection |

| Latif et al. [41] | Academic response (IT, cybersecurity) | Deep RNN architectures (DNN-1, DNN-2) | DRNN-2 achieved an accuracy of 88.52% for the mixed dataset |

| Class | Text |

|---|---|

| Real | “Im participating in the Trust Trading contest to win a thanks to” |

| LLaMA3.2 | “I am participating in the Trust Trading contest with the aim of winning a thank you.” |

| Phi3.5 | “Engaging in the Trust Exchange competition aims to secure gratitude” |

| Gemma2 | “I am competing in the Trust Trading contest for a prize.” |

| Qwen2.5 | “I’m joining the Trust Trading contest to win, thank you for the opportunity” |

| Mistral | “Competing in the Trust Trading competition with an aim to receive recognition” |

| LLaVA | “I’m joining the Trust Trading competition to potentially receive gratitude from someone.” |

| Model | Transformer Layers | Hidden State Size | Self-Attention Heads | Max Sequence Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed (DeBERTa base) | 12 | 768 | 12 | 512 |

| DistilBERT (base-uncased) | 6 | 768 | 12 | 512 |

| BERT base (uncased) | 12 | 768 | 12 | 512 |

| ELECTRA base | 12 | 768 | 12 | 512 |

| ALBERT base v1 | 12 | 768 | 12 | 512 |

| Hardware Information | Related Configuration |

|---|---|

| Operating system | Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS |

| System ram | 32 GB (gigabyte) |

| Disk | 2 TB (terabyte) |

| CUDA version | 12.2 |

| GPU | Nvidia GeForce RTX 3050 |

| GPU space | 20 GB (parallel) |

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.00002 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Epochs | 5 |

| Scheduler | Linear warmup scheduler |

| Model | Train | Valid | Test | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed (DeBerta-base) | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| DistilBERT | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| BERT base | 0.97 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| ELECTRA | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| ALBERT base V1 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Text | Actual | Predicted | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| “maintain privacy; avoid unnecessary exposure of personal details like name and address due to concerns over crypto privacy.” | Phi3.5 | Mistral | The concise and instructive tone, as well as the balanced phrasing, was evident across both model families, resulting in stylistic overlap. |

| “collaboratively envision a future where responsible ai ensures user privacy, laying the foundation for a transparent and decentralized data economy centered on individual privacy protections, with web3 cryptocurrency playing a key role.” | Qwen2.5 | LLaMA3.2 | The long, visionary phrasing and use of collective optimism resembled LLaMA’s generative style, and was confusing. |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision (Weighted) | Recall (Weighted) | F1-Score (Weighted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.52 |

| GaussianNB | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| Random forest | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Decision tree | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| XGBoost | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| AdaBoost | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| Voting (AdaBoost, GradientBoosting, XGBoost) | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Model | Parameter Grid | Best Parameters | Accuracy | Precision (Weighted) | Recall (Weighted) | F1-Score (Weighted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | “C”: [0.1, 1, 10], “solver”: [“liblinear”, “saga”] | {“C”: 0.1, “solver”: “saga”} | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| GaussianNB | “var_smoothing”: [1e-9, 1e-8, 1e-7] | {“var_smoothing”: 1e-09} | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| Random forest | “n_estimators”: [50, 100, 200], “max_depth”: [5, 10, none] | {“max_depth”: none, “n_estimators”: 200} | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Decision tree | “max_depth”: [5, 10, none], “min_sample_split”: [2, 5, 10] | {“max_depth”: none, “min_sample_split”: 2} | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| XGBoost | “n_estimators”: [50, 100, 200], “learning_rate”: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2], “max_depth”: [3, 5, 7] | {“learning_rate”: 0.2, “max_depth”: 7, “n_estimators”: 200} | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| AdaBoost | “n_estimators”: [50, 100, 200], “learning_rate”: [0.01, 0.1, 1.0] | {“learning_rate”: 1.0, “n_estimators”: 200} | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| Voting (AdaBoost, GradientBoosting, XGBoost) | [“hard”, “soft”] | {“voting”: “soft”} | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Study | Classes | Domain | Dataset Size | Model | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arshed et al. [26] | 3 classes (real, GPT, QuillBot) | Finance | Dataset-1 (1500) Dataset-2 (3000) | Random forest with Word2Vec | Dataset-1: 0.74 (74%) Dataset-2: 0.72 (72%) |

| Latif et al. [41] | 2 classes (human and ChatGPT) | IT, cybersecurity, and cryptography | 900 | DRNN-2 | 0.8852 (88.52% on full dataset) |

| Present Study | 7 classes (real, LLaMA3.2, Phi3.5, Gemma2, Qwen2.5, Mistral, and LLaVA) | Cryptocurrency | ~175,000 | Fine-tuned DeBERTa base | 0.94 (94%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arshed, M.A.; Gherghina, Ş.C.; Khalil, I.; Muavia, H.; Saleem, A.; Saleem, H. A Context-Aware Representation-Learning-Based Model for Detecting Human-Written and AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets Across Large Language Models. Math. Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060130

Arshed MA, Gherghina ŞC, Khalil I, Muavia H, Saleem A, Saleem H. A Context-Aware Representation-Learning-Based Model for Detecting Human-Written and AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets Across Large Language Models. Mathematical and Computational Applications. 2025; 30(6):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060130

Chicago/Turabian StyleArshed, Muhammad Asad, Ştefan Cristian Gherghina, Iqra Khalil, Hasnain Muavia, Anum Saleem, and Hajran Saleem. 2025. "A Context-Aware Representation-Learning-Based Model for Detecting Human-Written and AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets Across Large Language Models" Mathematical and Computational Applications 30, no. 6: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060130

APA StyleArshed, M. A., Gherghina, Ş. C., Khalil, I., Muavia, H., Saleem, A., & Saleem, H. (2025). A Context-Aware Representation-Learning-Based Model for Detecting Human-Written and AI-Generated Cryptocurrency Tweets Across Large Language Models. Mathematical and Computational Applications, 30(6), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca30060130