Research on the Characteristics and Patterns of Roof Movement in Large-Height Mining Extraction of Shallow Coal Seams

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analysis of Rotational Instability of Key Block Structures in Shallow Large-Height Mining

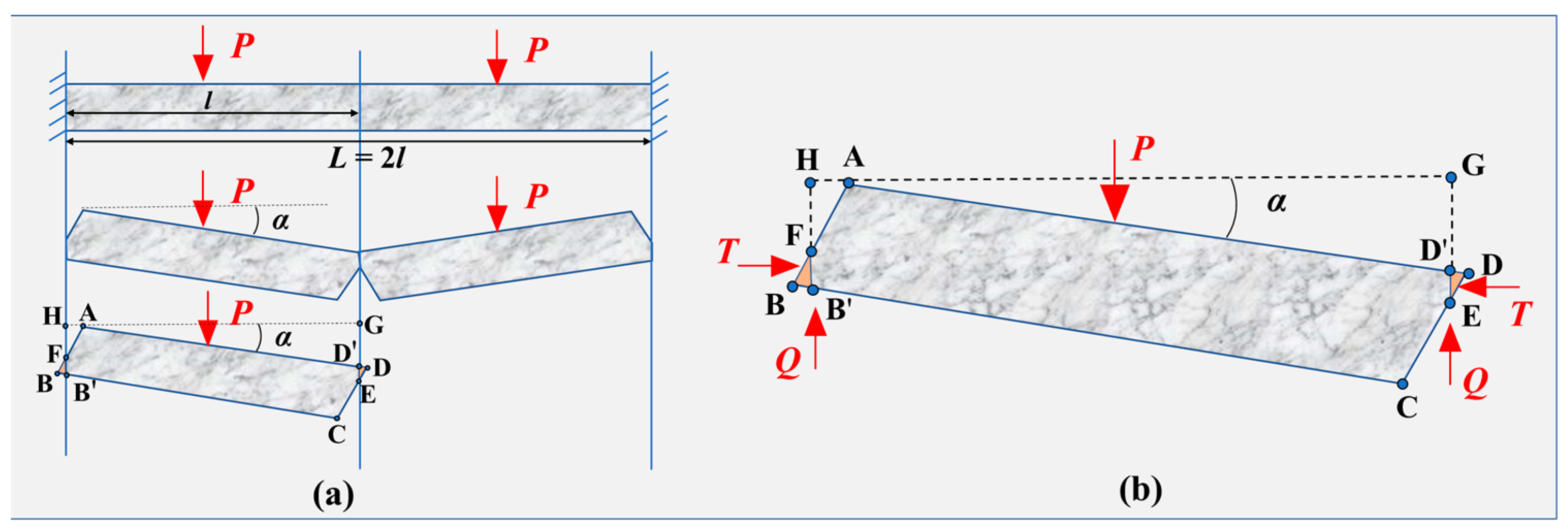

2.1. Establishment of the Mechanical Model

- (1)

- The subsidence motion of the key block occurs within a constrained space, specifically limited to L = 2l, where L represents the advancing distance of the working face and l denotes the length of the key block.

- (2)

- Considering the initial pressure exerted on the mining face, the key layer fractures into two blocks that are symmetrically positioned, with the two blocks undergoing opposing rotational movements.

- (3)

- It is assumed that the left and right hinge points of the two key blocks remain fixed, while vertical subsidence occurs at the center.

- (4)

- The deformation of the blocks is symmetrical, with horizontal stress generated by the deformation, and the stiffness of the surrounding rock mass constraining the block movement is sufficiently large.

- (5)

- For the sake of simplification in the analysis, the effects of geological structures and inclined strata are temporarily disregarded. It is considered that vertical failure occurs in the key layer, and the roof strata are horizontal.

- (6)

- The rock strata of the key blocks are homogeneous and isotropic.

2.2. Solution and Analysis of the Mechanical Model

2.3. Pattern of Horizontal Thrust Variation

2.4. Analysis of the Balance Conditions of Key Blocks

2.5. Supporting Structure Working Resistance

3. Analysis of the Roof Movement Patterns During Large-Height Mining of Shallow Coal Seams

3.1. Establish a Physical Simulation Model

- (1)

- After the model was completed and dried for 5 days, the glass panels were removed to arrange the displacement measurement points (as shown in Figure 8b). Reference points for total station measurements were selected, and initial readings for each measurement point were recorded.

- (2)

- To minimize boundary effects, a cut was excavated 10 m from one edge of the model, with a width of 8 m and a mining height of 5.5 m. A four-column hydraulic support was placed within the cut to simulate the actual mining environment.

- (3)

- In accordance with the mining operation schedule, and based on time and geometric similarity ratios, each coal cut was allocated 11 min, with an advance of 0.8 m, resulting in a total daily advancement of 12 m to simulate the real mining process. The cumulative advancement of the working face reached 130 m. Throughout the simulation, the total station and digital camera were utilized in conjunction to monitor and record the roof movement in real-time.

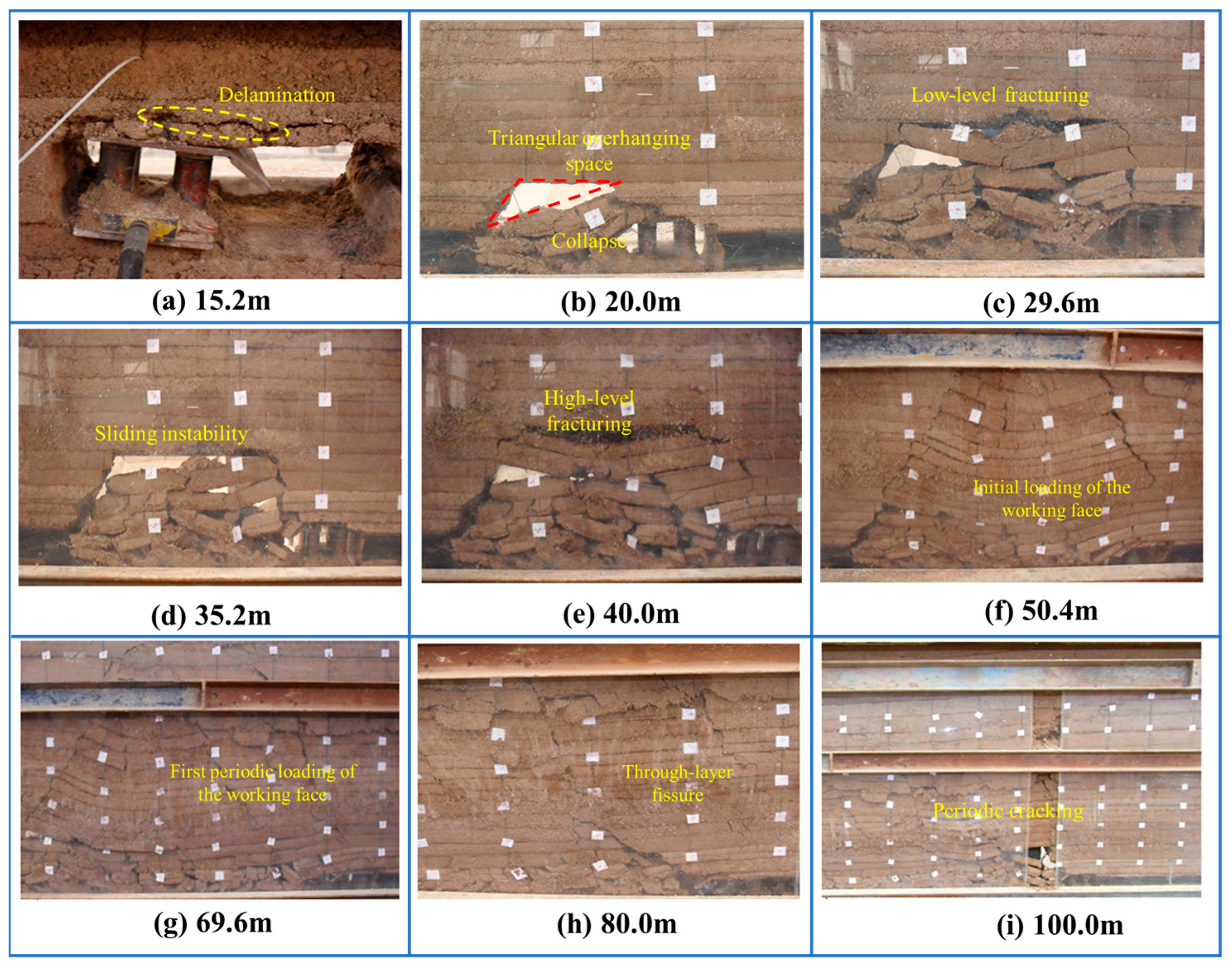

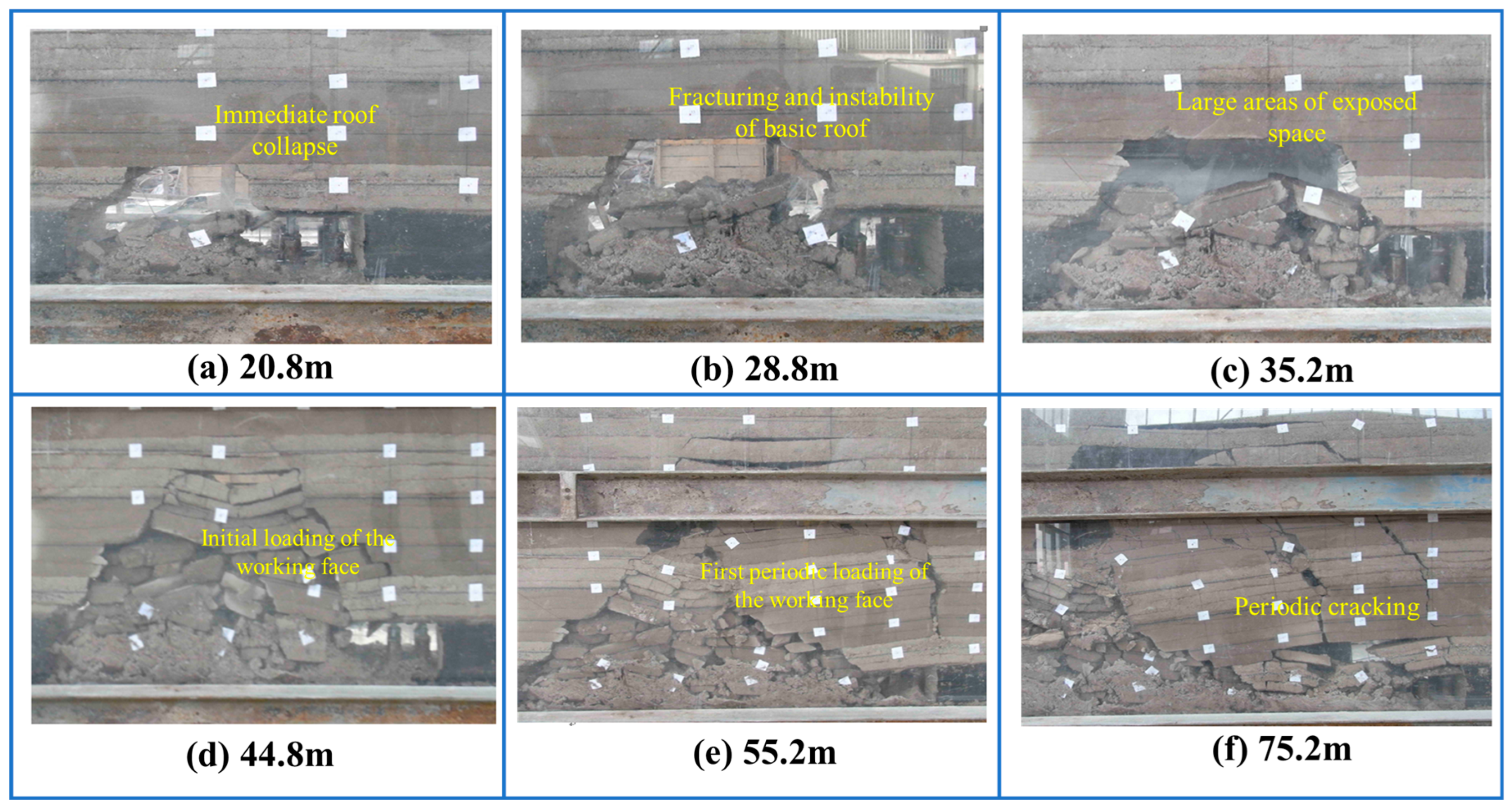

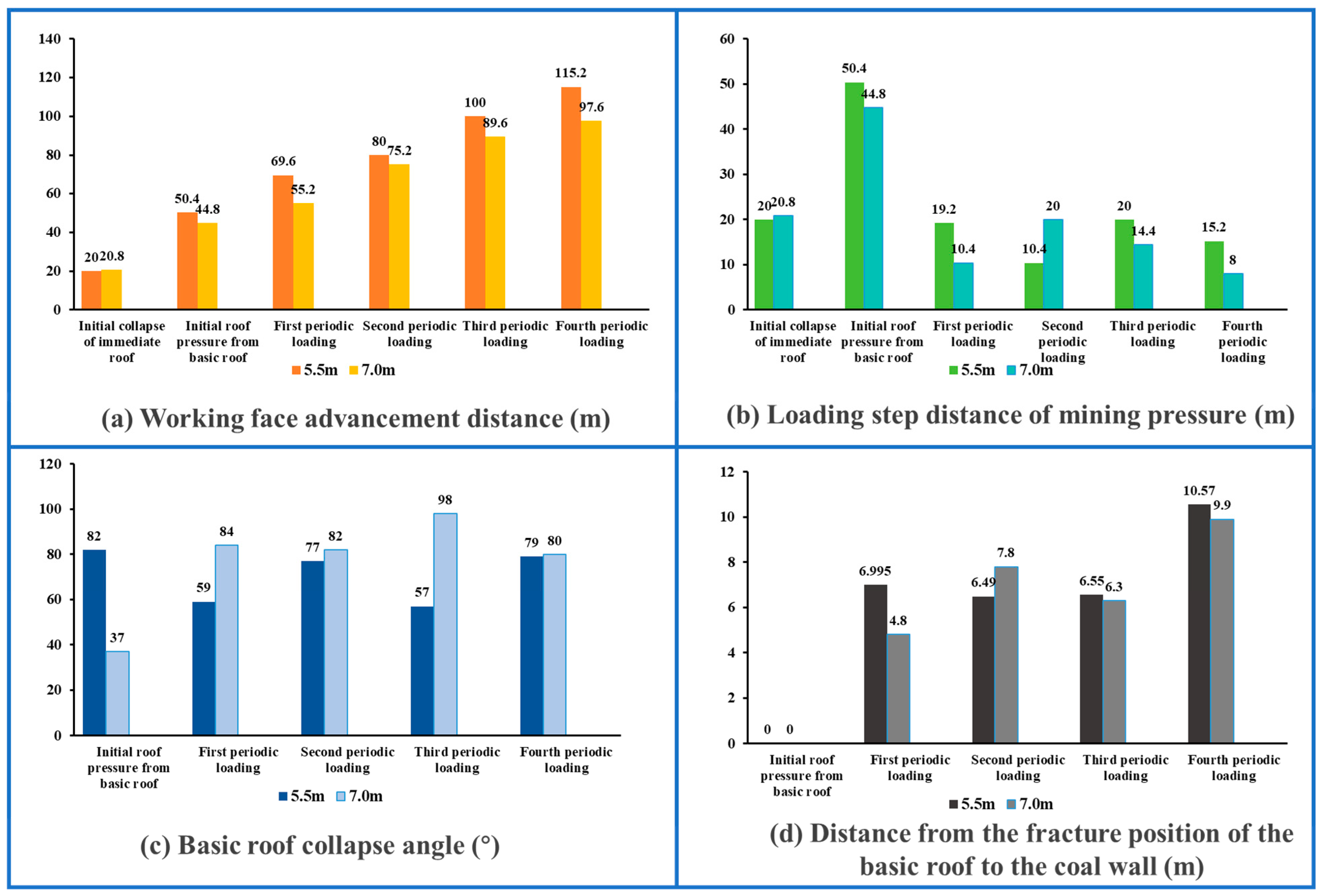

3.2. Analysis of the Roof Collapse Process

3.3. Analysis of the Characteristics of Roof Movement

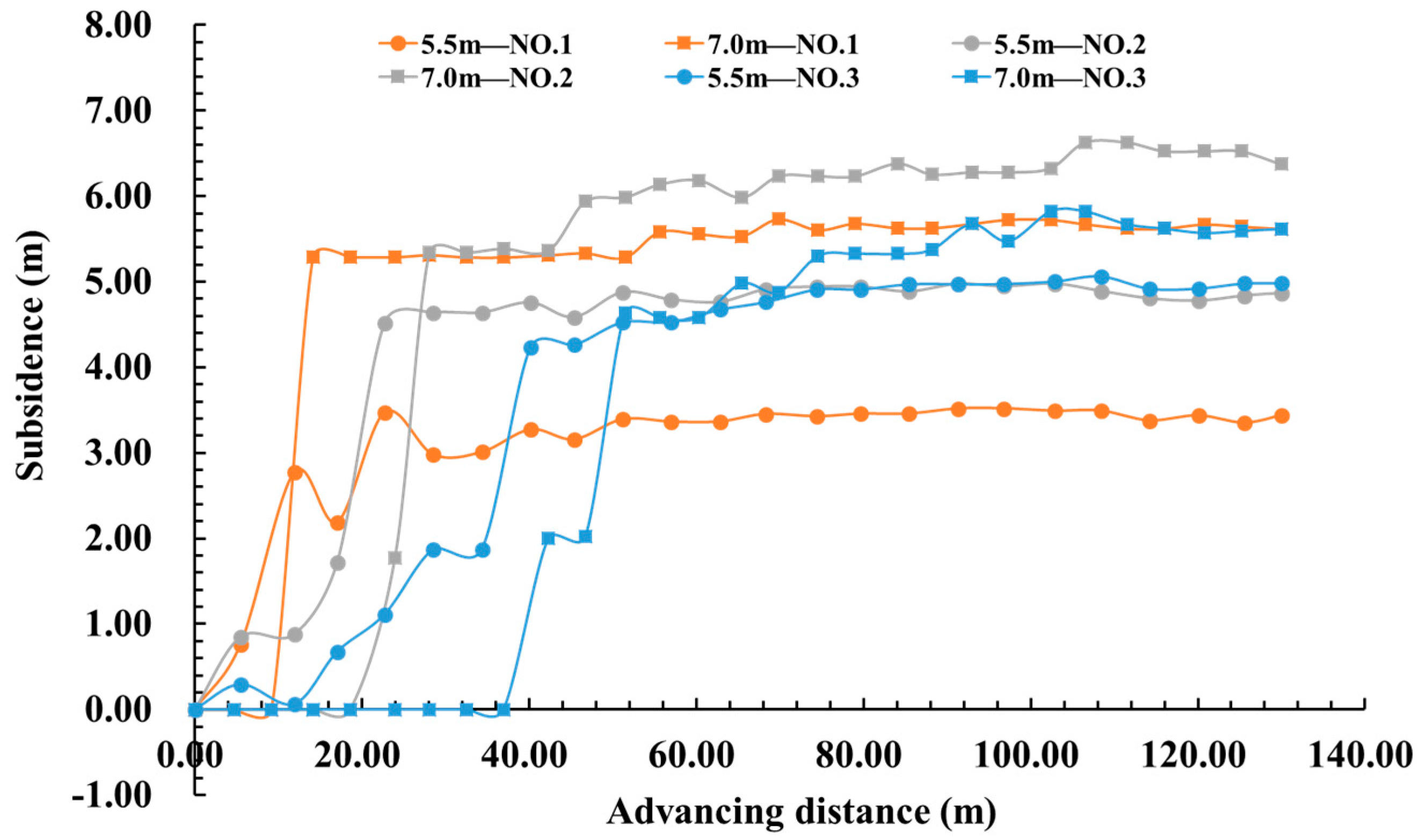

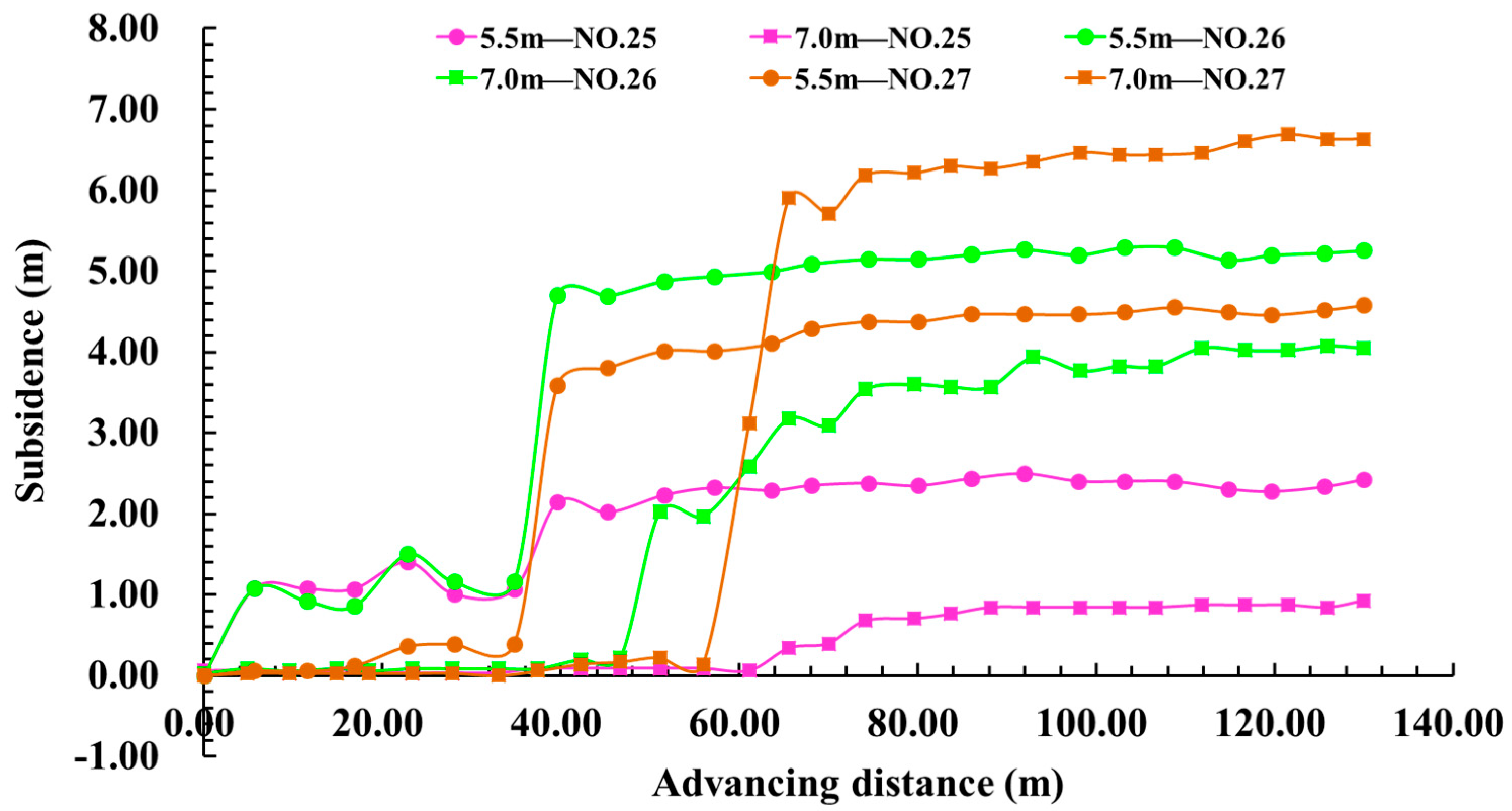

3.4. Analysis of Roof Subsidence Displacement

4. Conclusions

- (1)

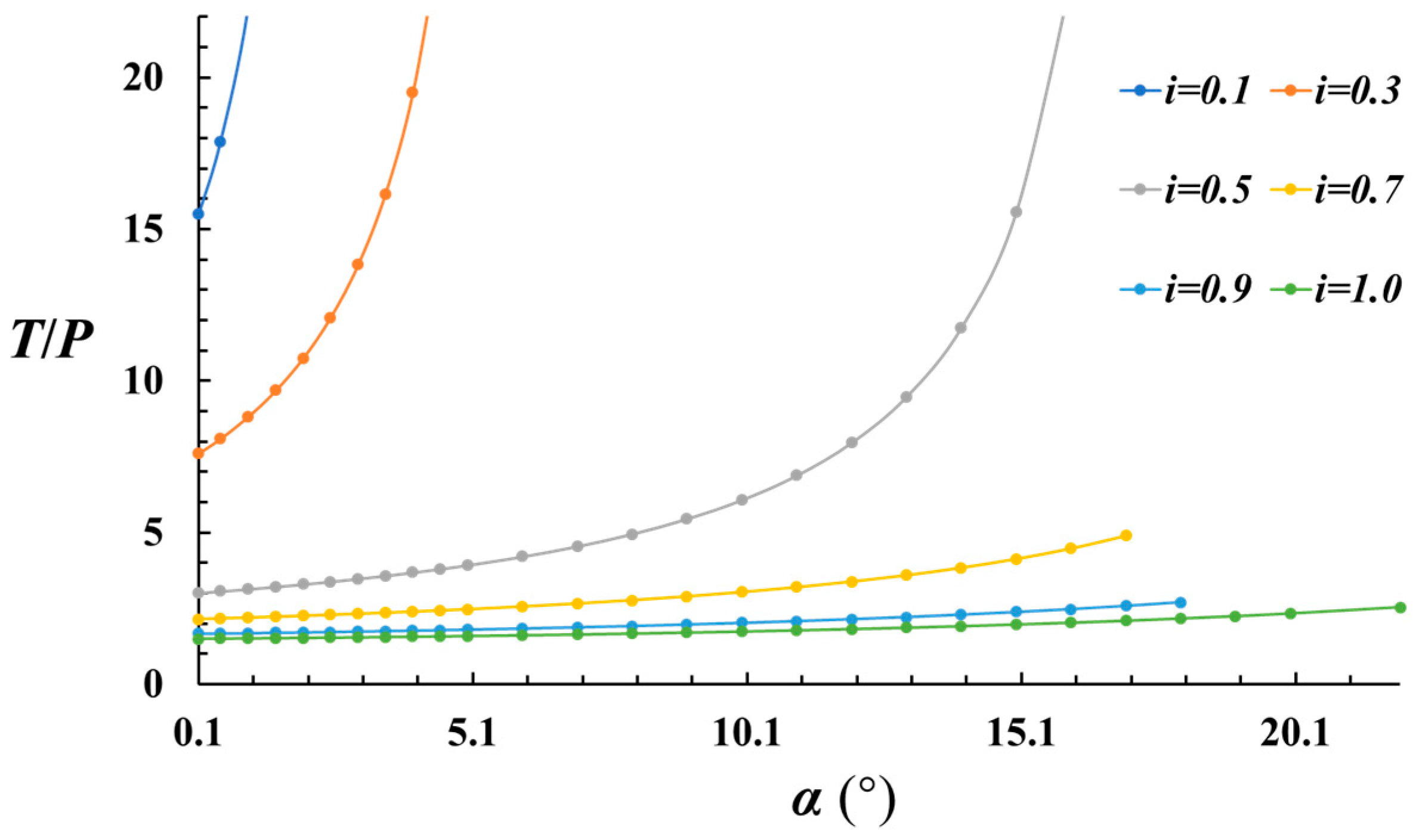

- A mechanical model was established to calculate the horizontal thrust during the rotational instability of key blocks, considering the deformation of the block as it undergoes rotational subsidence under large-height mining conditions. The horizontal thrust increases non-linearly with the rising rotation angle. When the block’s dimension ratio is less than 0.5, the rate of increase in horizontal thrust with respect to the rotation angle is higher.

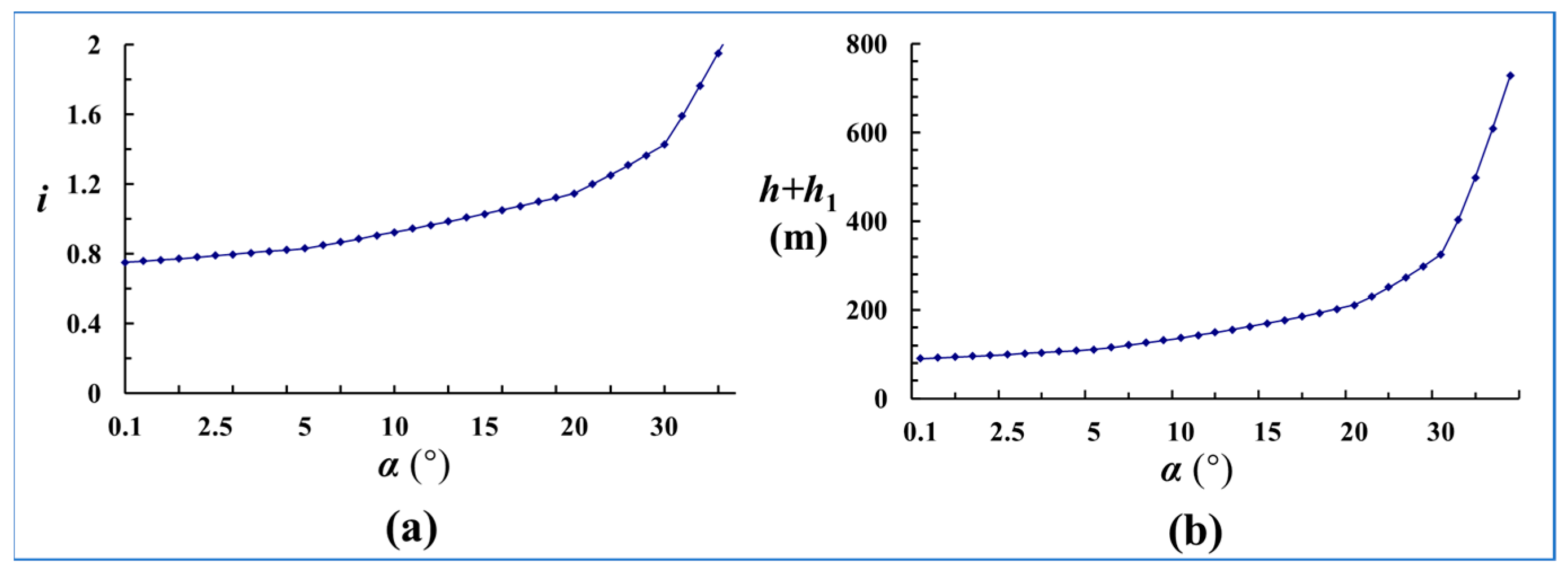

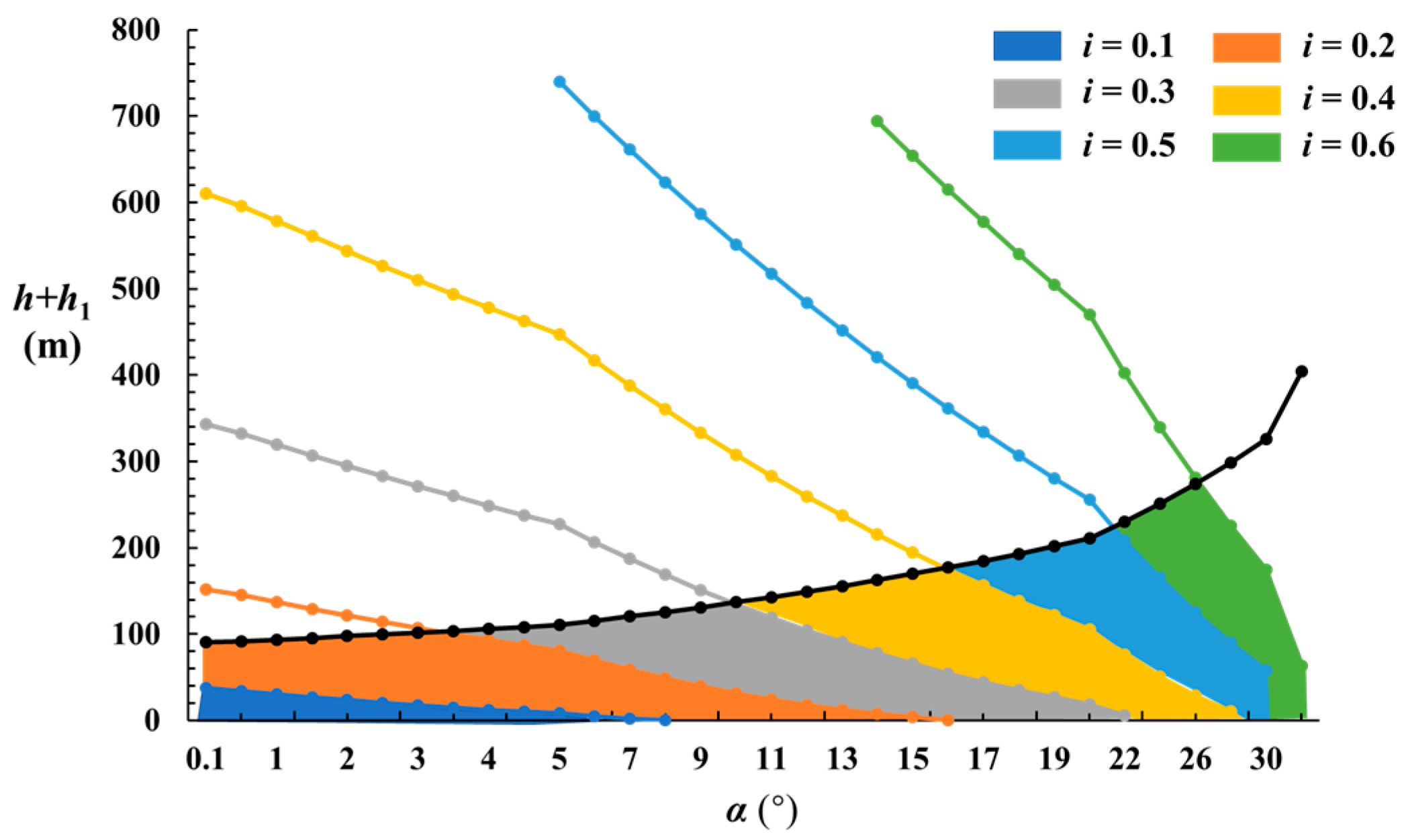

- (2)

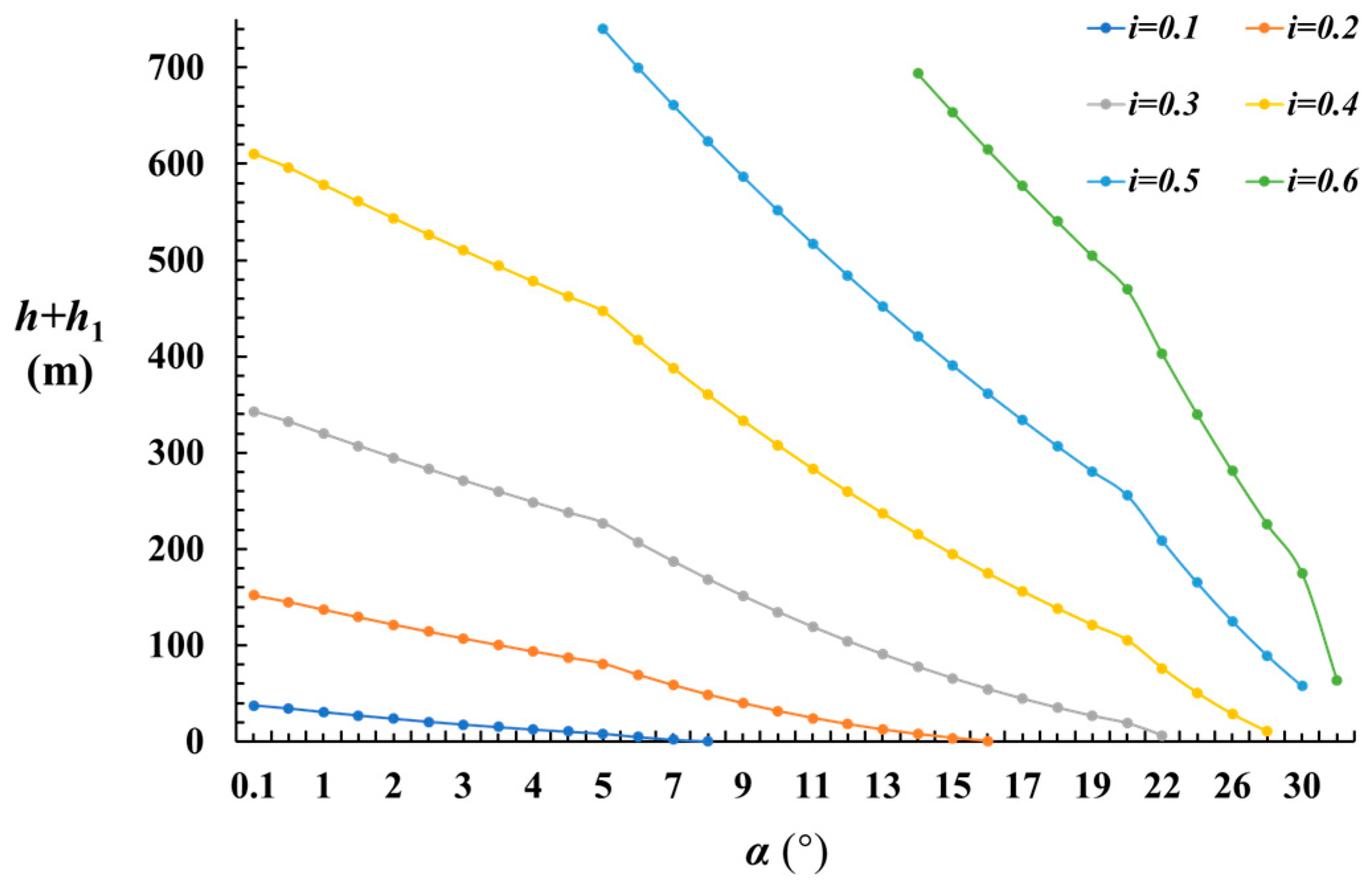

- Two modes of instability are prone to occur in key blocks during large-height mining of shallow coal seams: sliding instability and deformation instability. The equilibrium conditions of the key block were analyzed, leading to a regression equation relating the dimension ratio to the limit bearing thickness during rotational subsidence. To prevent sliding instability, the dimension ratio of the key block should be less than 0.75. As the rotation angle increases, the corresponding dimension ratio for maintaining limit equilibrium also increases. Practically, once the rotation angle of the key block exceeds 10°, sliding instability becomes likely. A smaller rotation angle allows for a larger dimension ratio, enhancing the bearing capacity of the key block and reducing the likelihood of deformation instability.

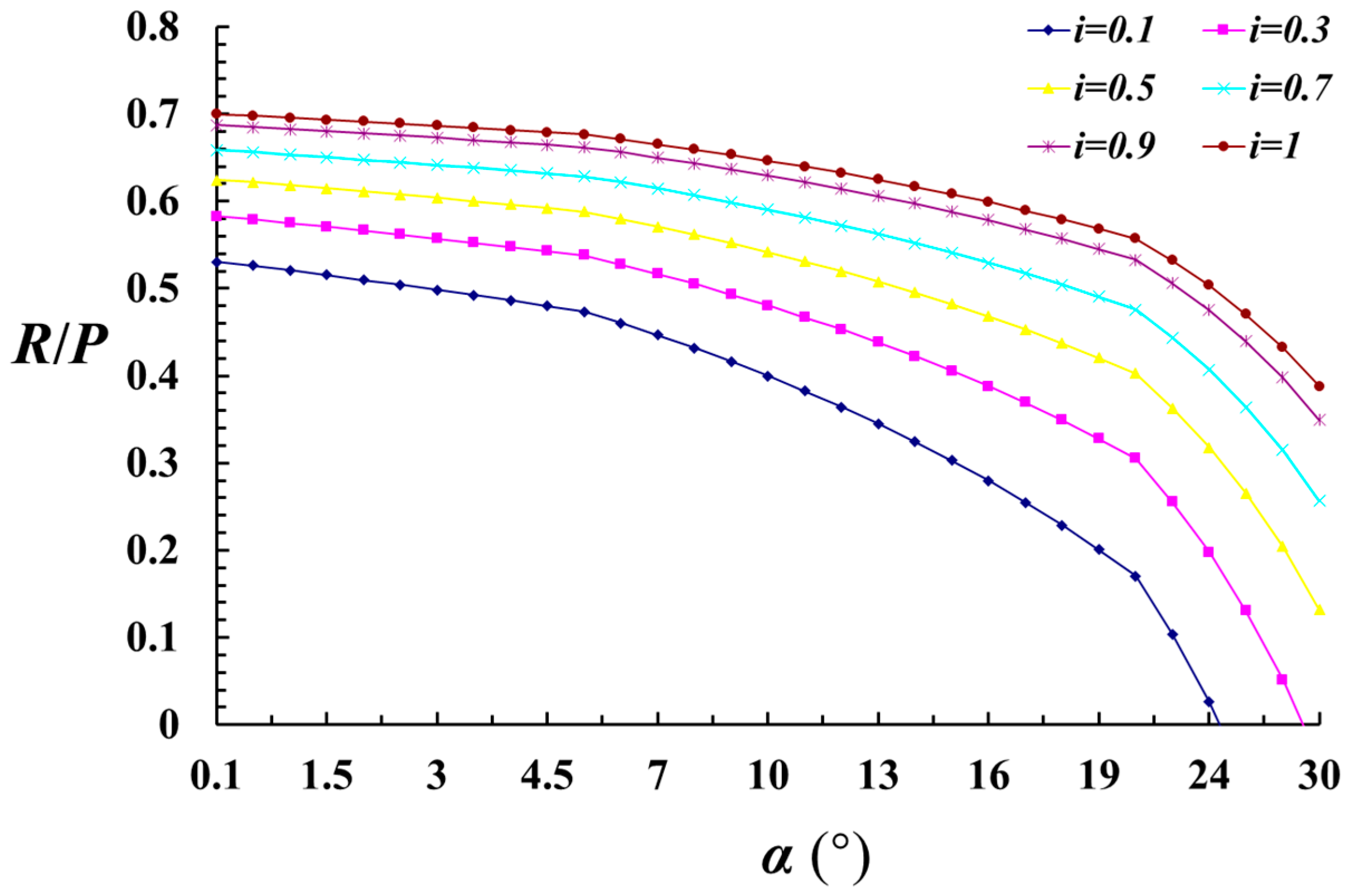

- (3)

- Reasonable support working resistance necessary to prevent sliding instability of the basic roof during large-height mining operations was determined. During the rotational subsidence of the key block, the support resistance gradually decreases as the rotation angle increases. Beyond a rotation angle of 10°, the support resistance declines rapidly with increasing rotation angle. Additionally, as the dimension ratio increases, the support resistance required to control sliding instability of the key block also increases.

- (4)

- Based on physical simulation experiments, the characteristics of roof movement can be generally categorized into three stages: immediate roof collapse, stratified fracturing and instability of the basic roof, and periodic fracturing of the basic roof. As mining height increases, instability immediately follows the fracturing of the basic roof, failing to form an effective key block hinge structure. The increased rotational space significantly enlarges the opening of through-layer fissures formed in front of the working face. Moreover, higher mining heights effectively shorten the loading step distance of mining pressure, increase the collapse angle of the basic roof, and elevate the risk of sudden collapse, leading to unexpected loading on the working face.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, F. Integrated simulation and monitoring to analyze failure mechanism of the anti-dip layered slope with soft and hard rock interbedding. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Standard MT/T 773-1998; Norms for Classification of Hydrogeological Condition of Coal Mine. National Coal Industry Bureau: Beijing, China, 1998.

- Huang, Q. Ground pressure behavior and definition of shallow seams. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 2002, 21, 1174–1177. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ma, L. Study on the mechanism and control of strong ground pressure in the mining of shallow buried close-distance coal seam passing through the loess hilly region. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, T.; Miao, C. A novel method of deep and shallow combined roof cutting and constant resistance support for enhancing deep mining roadway stability. Min. Metall. Explor. 2025, 42, 1421–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Lu, X. Quantitative research on sensitive factors of coal wall rib spalling in full mechanized caving face with large mining height. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Shen, L.; Cao, Z.; Feng, D.; Li, Z.; Yu, Y. Development rule of ground fissure and mine ground pressure in shallow burial and thin bedrock mining area. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, J.; Xu, J. Structural characteristics of key strata and strata behaviour of a fully mechanized longwall face with 7.0 m height chocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 58, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qin, G.; Yang, T.; Wang, B.; He, Y.; Gao, S. Mechanism of mining-induced dynamic loading in shallow coal seams crossing Maoliang terrain. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Ran, Q.; Zou, Q.; Ding, L.; Yang, Y.; Ma, T. Characteristics of overburden fracture conductivity in the shallow buried close coal seam group and its effect on low-oxygen phenomena. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 047103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. Stability Analysis of Old Empty Area After Shallow Multi-Coal Mining and Study on Grouting Filling Treatment Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Liaoning Technical University, Fuxin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, W.; Zhang, T.; Yu, X.; Kong, H.; Wang, C. Design of roadway mining filled by tailings paste and study on surface subsidence control in shallow seam mining. J. China Coal Soc. 2015, 40, 1326–1332. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Pang, Y.; Ren, H.; Ma, Y. Coal safe and efficient mining theory, technology and equipment innovation practice. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 903–913. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X. Research status of strata control and large mining height fully-mechanized mining technology in China. Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 47, 37–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Shen, W.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, P.; Qin, Q.; Li, Z. Research on the mechanism and control technology of coal wall sloughing in the uiltra-large mining height working face. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Lei, Y.; Zhao, F.; Xu, G.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Key technology and equipment for fully mechanized mining with extra-large shearing height of 10 m in extra-thick coal seam. J. China Coal Soc. 2025, 50, 1849–1875. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Hu, B. Theoretical analysis of the movement law of top coal and overburden in a fully mechanized top-coal caving face with a large mining height. Processes 2022, 10, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Q.; Luo, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, S.; Wang, H. Coal wall spalling mechanism and grouting reinforcement technology of large mining height working face. Sensors 2022, 22, 8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, Z.; Ji, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, H. Research on the influence of the key stratum position on the support working resistance during large mining height top-coal caving mining. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6690280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, P.; Cui, S.; Fan, M.; Qiu, Y. Mechanism and surrounding rock control of roadway driving along gob in shallow-buried, large mining height and small coal pillars by roof cutting. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 2254–2267. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Liang, Y.; Zou, Q. Determination of working resistance based on movement type of the tirst subordinate key stratum in a fully mechanized face with large mining height. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zou, Y.; Gui, T.; Chen, F. Research on gob-side entry retaining technology inclined fully mechanized mining face with large mining height. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lei, S.; Li, Y. Adaptive intelligent coupling control of hydraulie support and working face system for 6–10 m super high mining in thick coal seams. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 276–288. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Song, J.; Jia, M. New approach for the digital reconstruction of complex mine faults and its application in mining. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Feng, G.; Guo, J.; Qian, R.; Feng, W.; Bai, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Dias, D. Strength deterioration mechanism of sandstone subjected to low-frequency dynamic disturbance under the varying static pre-stress levels. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y. Sediment instability caused by gas production from hydrate-bearing sediment in northern south China sea by horizontal wellbore: Sensitivity analysis. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 1667–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, Q.; Feng, G.; Bai, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, S.; Wen, X. Effect of water intrusion on mechanical behaviors and failure characteristics of backfill body and coal pillar composite specimens under uniaxial compression. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 502, 145388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J. Effects of geological and fluid characteristics on the injection filtration of hydraulic fracturing fluid in the wellbores of shale reservoirs: Numerical analysis and mechanism determination. Processes 2025, 13, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, F.; Tang, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, F. Fracture characteristics and disaster-causing mechanism of rock strata based on arch mechanical model of plane contact block. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 4178599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, A.; Mao, X.; Li, B. Theoretical analysis on stress and deformation of overburden key stratum in solid filling coal mining based on the multilayer winkler foundation beam model. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 6693888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Research and progress of coal mine green mining in 20 Years. Coal. Sci. 2020, 48, 1–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Yang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, X.; Liu, Y.; Hou, J.; Zheng, W.; Ye, Q. Mechanical model for analyzing the water-resisting key stratum to evaluate water inrush from goaf in roof. Geomech. Eng. 2022, 28, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Shi, P.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y. Mining Pressure and Strata Control; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Xuzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Huang, Q. Investigating the mechanism of strong roof weighting and support resistance near main withdrawal roadway in large-height mining face. Lithosphere 2024, 2024, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Qin, Q. Study on surrounding rock control and support stability of ultra-large height mining face. Energies 2022, 15, 6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, D.; Xu, W.; Zambrano-Narvaez, G.; Zhan, L.; Chen, Y. Application of physical model test in underground engineering: A review of methods and technologies. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 52, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, C.; He, Y. Research on the movement of overlying strata in shallow coal seams with high mining heights and ultralong working faces. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Liang, Y.; Ye, C.; Ning, Y.; Ma, T.; Kong, F. Failure analysis of overlying strata during inclined coal seam mining: Insights from acoustic emission monitoring. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Block size coefficient (i) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Ultimate bearing thickness (h + h1)/(m) | 37.6 | 100 | 135 | 175 | 209 | 274 |

| Layer | Lithology | Thickness (m) | Density (kg/m3) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Similarity Ratio | Sand (kg) | Cement (kg) | Calcium Carbonate (kg) | Gypsum (kg) | Water (kg) | Borax (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Windblown sand | 11.70 | 1700 | 238.7 | ||||||||

| 2 | Siltstone | 8.60 | 2460 | 40.6 | 35 | 655 | 152.9 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 33.6 | 336 | |

| 3 | Sandy mudstone | 5.10 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 346 | 74.6 | (9.3) | 14 | 9.3 | 186 | |

| 4 | Coarse sandstone | 10.28 | 2430 | 36.6 | 35 | 855 | 185.7 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 20.4 | 204 | |

| 5 | Fine sandstone | 7.03 | 2500 | 44.6 | 32 | 955 | 131.9 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 14.3 | 143 | |

| 6 | Sandy mudstone | 9.8 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 337 | 143.3 | (13.4) | 31.4 | 25.6 | 512 | |

| 7 | Coarse sandstone | 11.24 | 2430 | 36.6 | 35 | 855 | 203.1 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 22.3 | 223 | |

| 8 | Sandy mudstone | 27.52 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 337 | 402.4 | (37.7) | 88.0 | 71.9 | 1437 | |

| 9 | Coarse sandstone | 9.89 | 2430 | 36.6 | 35 | 855 | 178.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 19.6 | 196 | |

| 10 | Sandy mudstone | 6.17 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 337 | 90.2 | (8.5) | 19.7 | 16.1 | 322 | |

| 11 | Fine sandstone | 7.27 | 2500 | 44.6 | 32 | 955 | 136.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 14.8 | 148 | |

| 12 | Sandy mudstone | 4.16 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 337 | 60.8 | (5.7) | 13.3 | 10.9 | 217 | |

| 13 | Coal seam | 5.5 (7.0) | 1480 | 10.5 | 15 | 373 | 53.1 | (11.6) | 5 | 6.6 | 133 | |

| 14 | Siltstone | 1.48 | 2460 | 40.6 | 35 | 655 | 26.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 42 | |

| 15 | Sandy mudstone | 3.25 | 2240 | 22.8 | 23 | 337 | 47.5 | (4.5) | 10.4 | 8.5 | 170 | |

| 16 | Fine sandstone | 5.70 | 2500 | 44.6 | 32 | 955 | 107 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 11.6 | 116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, K. Research on the Characteristics and Patterns of Roof Movement in Large-Height Mining Extraction of Shallow Coal Seams. Processes 2025, 13, 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093026

Fu Y, Zhao Z, Ma K. Research on the Characteristics and Patterns of Roof Movement in Large-Height Mining Extraction of Shallow Coal Seams. Processes. 2025; 13(9):3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Yuping, Zhen Zhao, and Kai Ma. 2025. "Research on the Characteristics and Patterns of Roof Movement in Large-Height Mining Extraction of Shallow Coal Seams" Processes 13, no. 9: 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093026

APA StyleFu, Y., Zhao, Z., & Ma, K. (2025). Research on the Characteristics and Patterns of Roof Movement in Large-Height Mining Extraction of Shallow Coal Seams. Processes, 13(9), 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13093026