Research on Dynamic Control Methods for Fine-Scale Water Injection Zones Based on Seepage Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement

3. Seepage Resistance Calculation Model

4. Establish Criteria for Determining Seepage Resistance

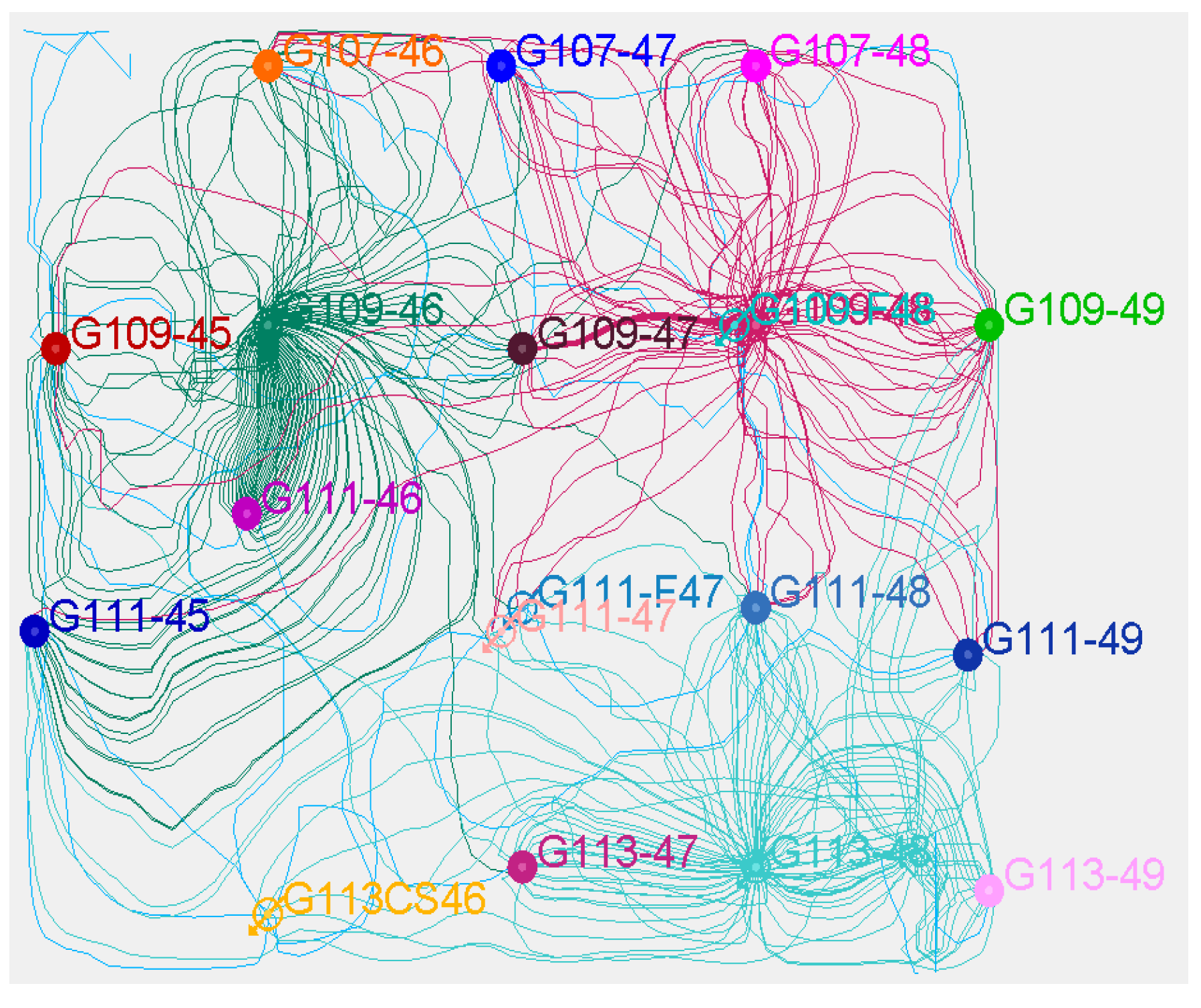

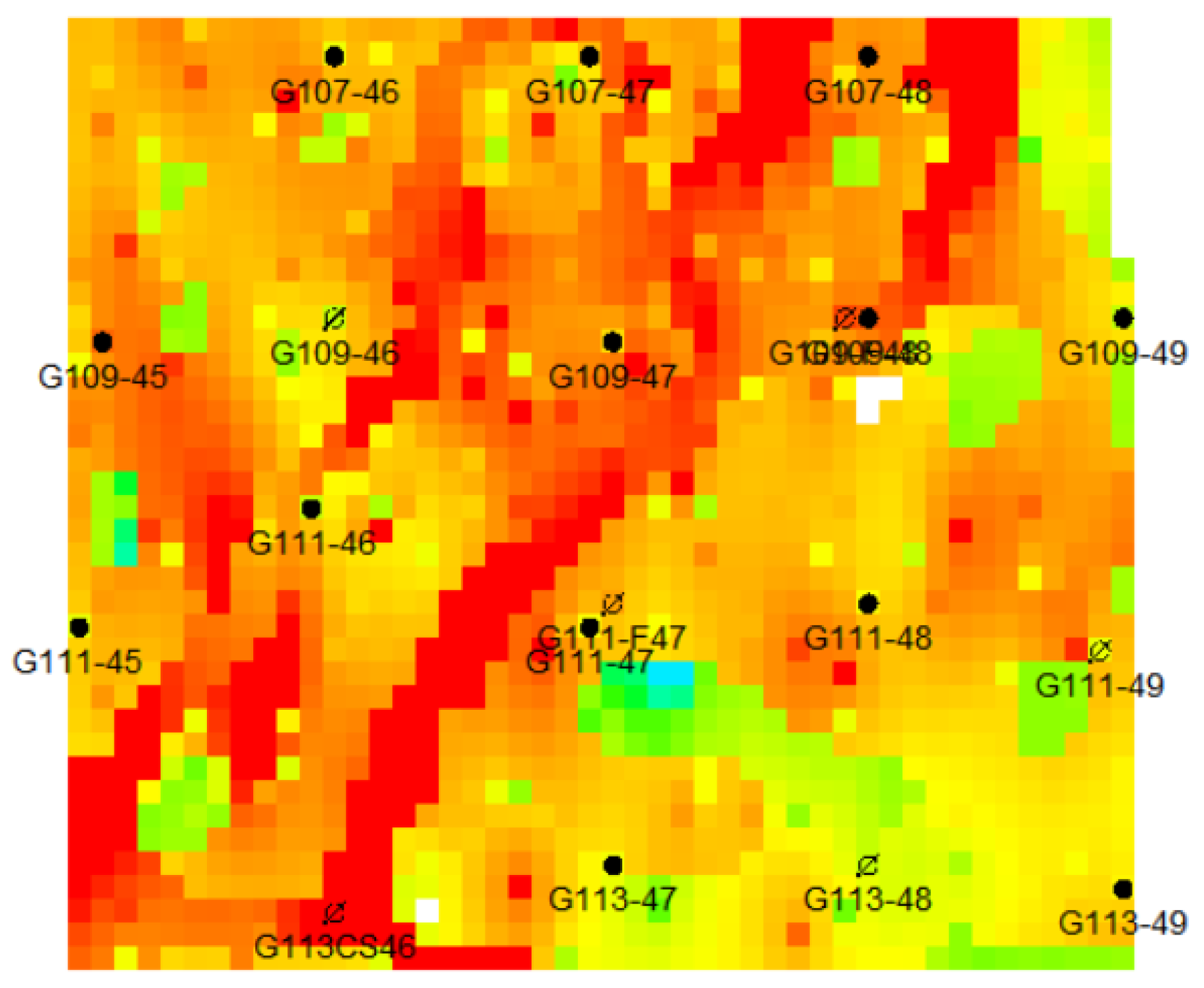

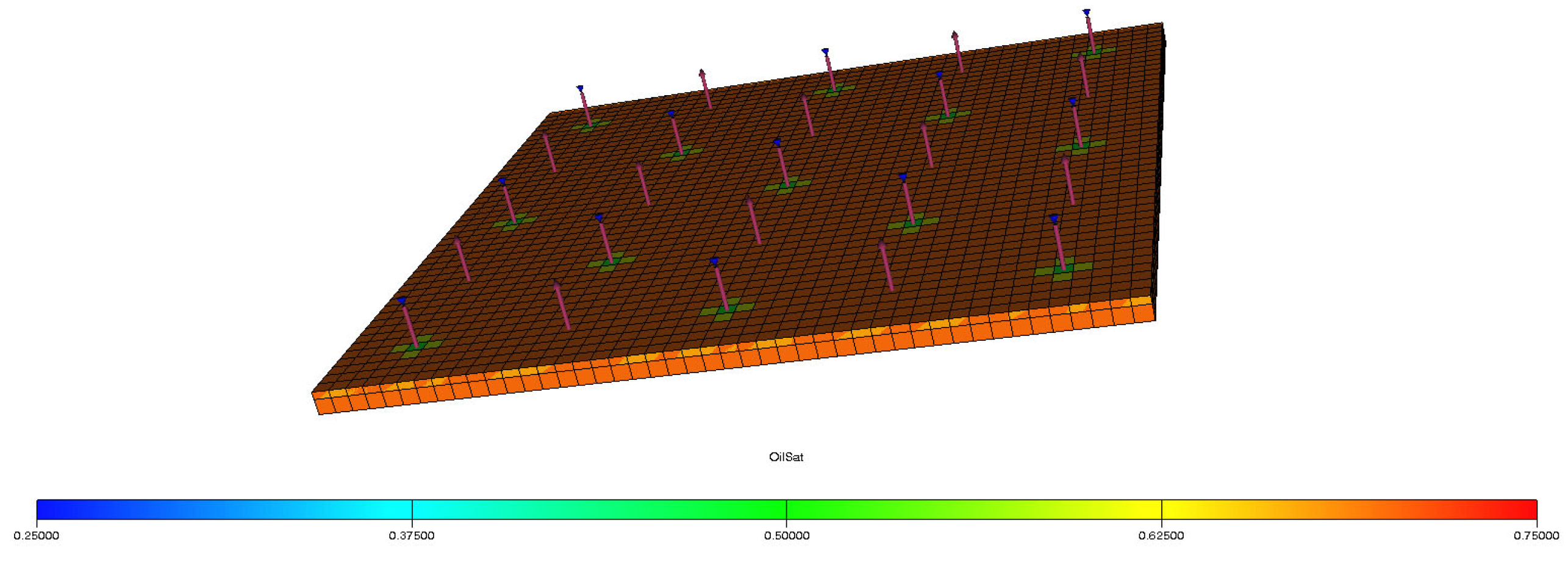

5. Research on Dynamic Regulation Methods for Layer Segments

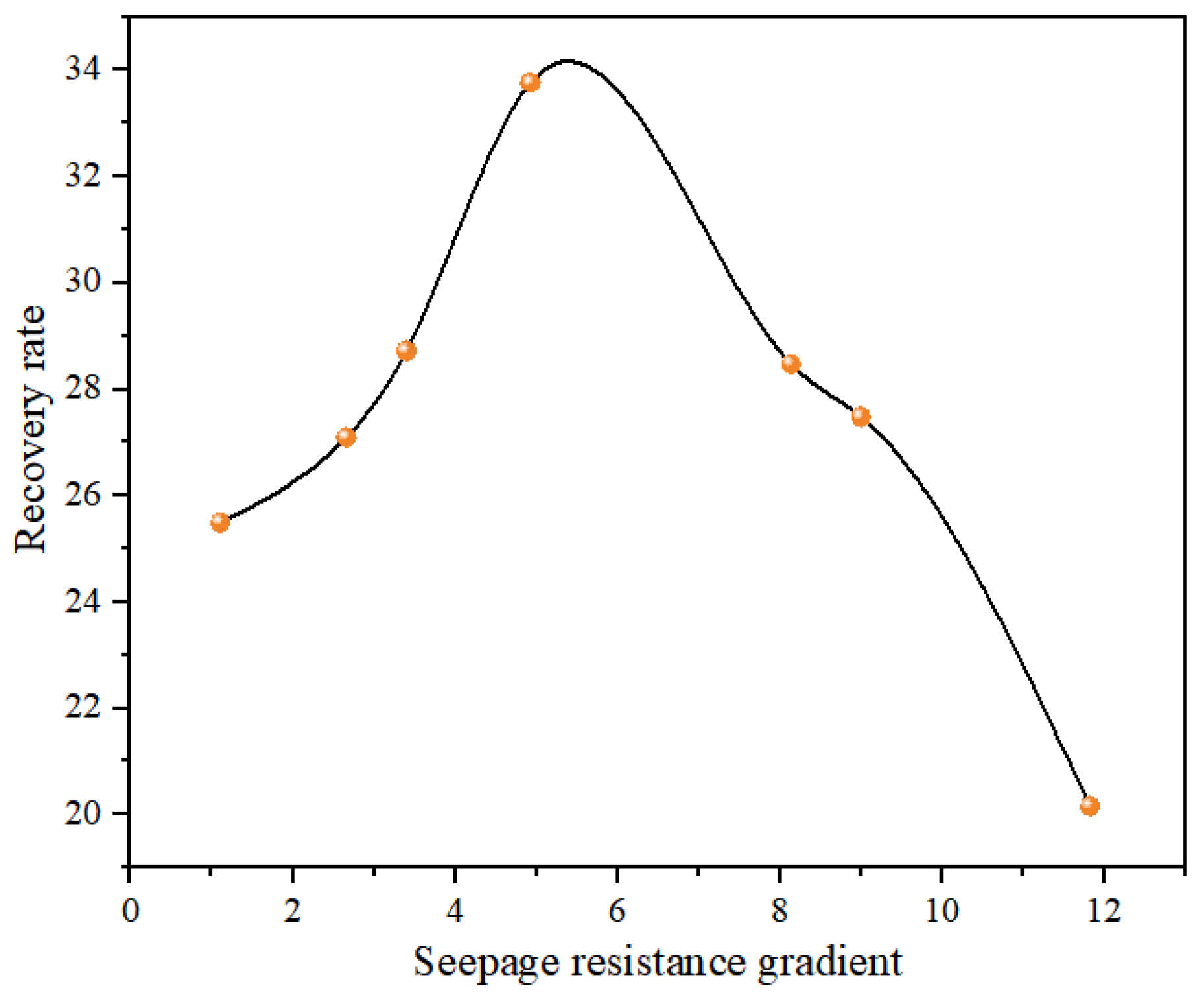

5.1. Optimal Gradient for Seepage Resistance

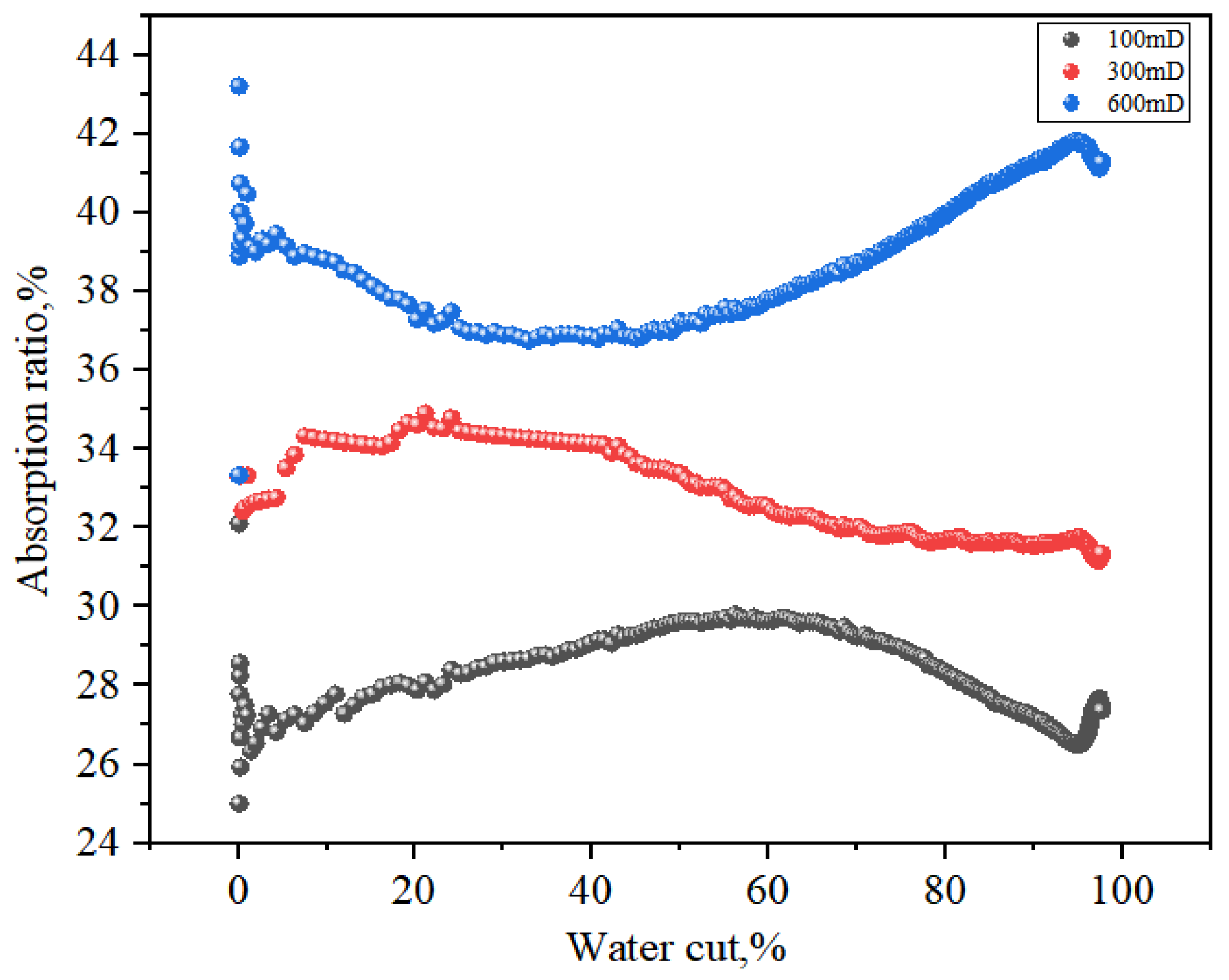

5.2. The Relationship Between Liquid Absorption Ratio and Seepage Resistance

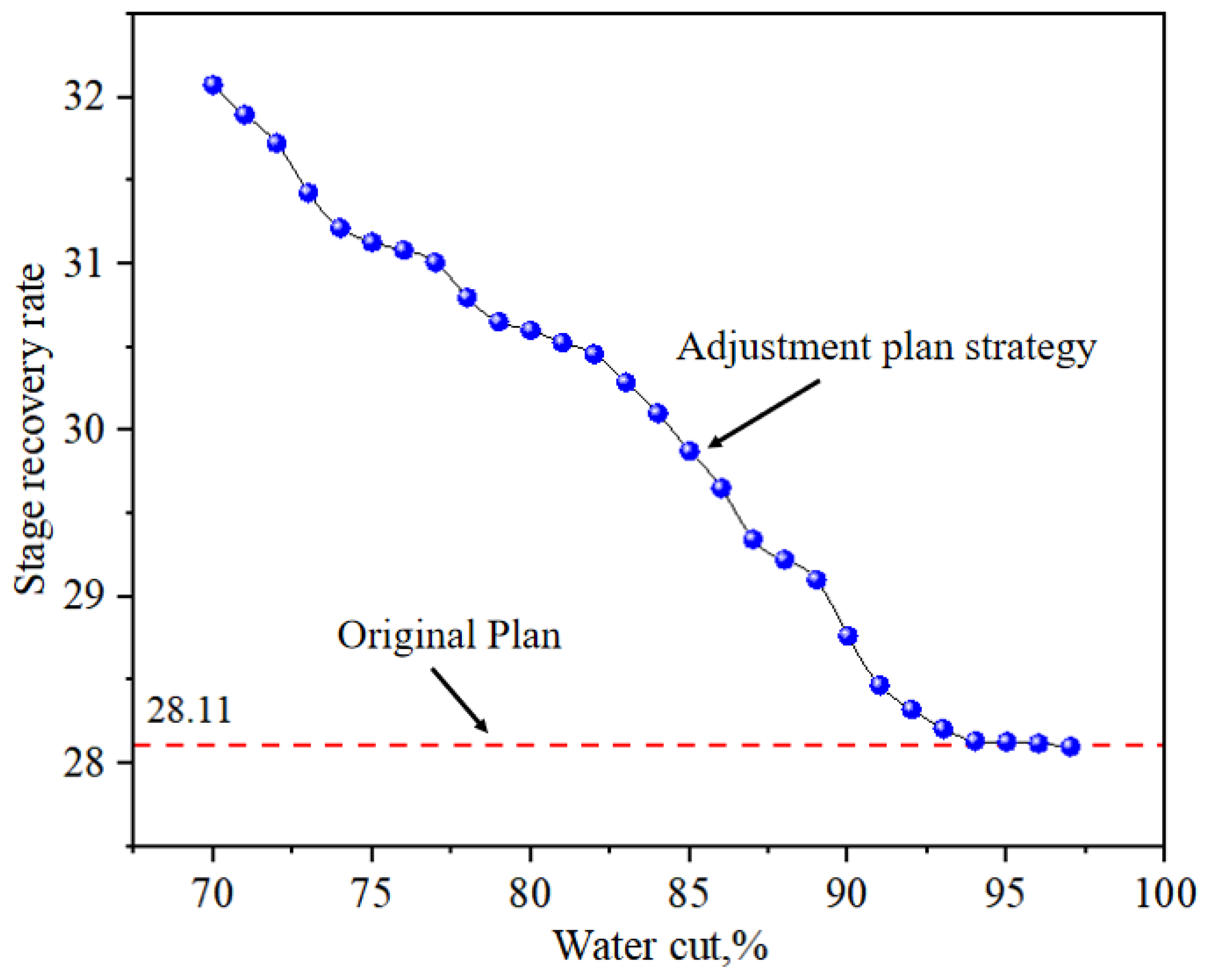

5.3. Water Injection Control Strategy

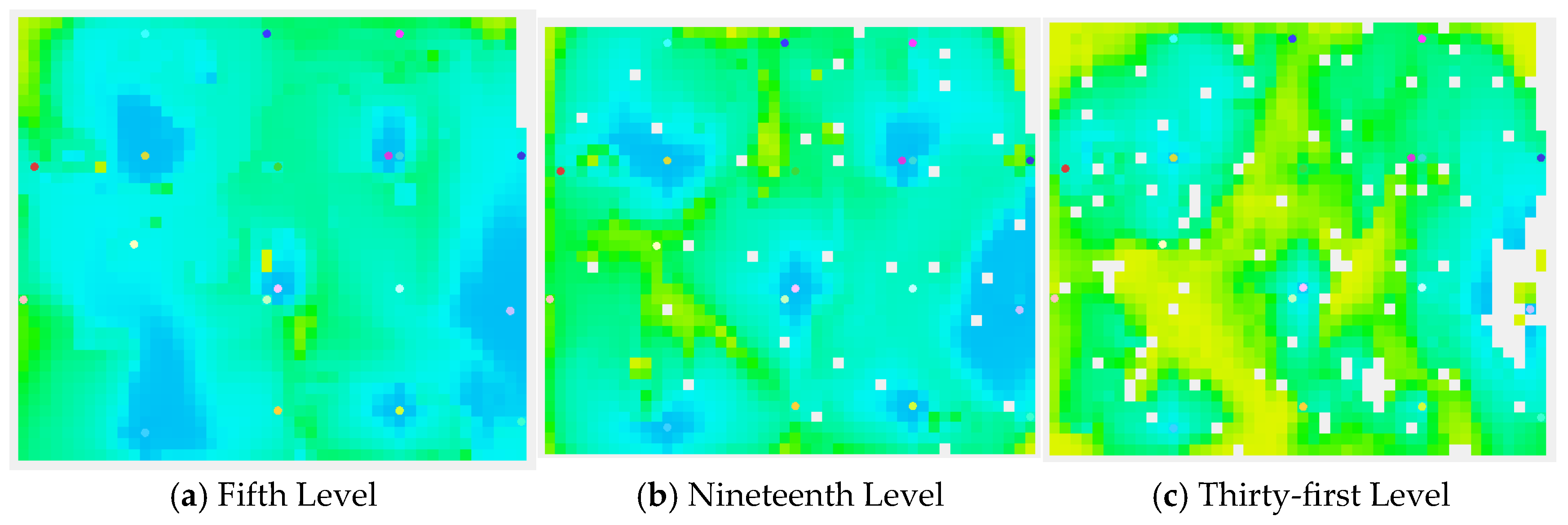

6. Practical Application

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Water Cut, % | Layer-Segment Combination | Seepage Resistance Gradient | Stage Recovery Rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70 | G11–G18 | 2.80 | 32.075 |

| G19–G111 | 2.04 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.79 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.68 | ||

| 71 | G11–G18 | 2.77 | 31.896 |

| G19–G111 | 2.05 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.78 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.67 | ||

| 72 | G11–G18 | 2.77 | 31.724 |

| G19–G111 | 2.06 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.77 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.68 | ||

| 73 | G11–G18 | 2.89 | 31.428 |

| G19–G111 | 2.07 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.75 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.69 | ||

| 74 | G11–G18 | 3.33 | 31.215 |

| G19–G111 | 2.09 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.73 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.71 | ||

| 75 | G11–G18 | 3.55 | 31.131 |

| G19–G111 | 2.10 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.72 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.73 | ||

| 76 | G11–G18 | 3.60 | 31.082 |

| G19–G111 | 2.11 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.69 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.76 | ||

| 77 | G11–G18 | 3.58 | 31.009 |

| G19–G111 | 2.11 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.68 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.79 | ||

| 78 | G11–G18 | 3.55 | 30.998 |

| G19–G111 | 2.09 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.67 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.82 | ||

| 79 | G11–G18 | 3.51 | 30.998 |

| G19–G111 | 2.06 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.67 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.85 | ||

| 80 | G11–G18 | 3.46 | 30.698 |

| G19–G111 | 2.00 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.67 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.90 | ||

| 81 | G11–G18 | 3.43 | 30.589 |

| G19–G111 | 1.94 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.67 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.94 | ||

| 82 | G11–G18 | 3.41 | 30.458 |

| G19–G111 | 1.85 | ||

| G112–G116 | 2.68 | ||

| G117–G120 | 4.99 | ||

| 83 | G11–G18 | 3.39 | 30.289 |

| G19–G111 | 1.77 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.83 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.76 | ||

| 84 | G11–G18 | 3.40 | 30.103 |

| G19–G111 | 1.76 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.83 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.76 | ||

| 85 | G11–G18 | 3.39 | 29.876 |

| G19–G111 | 1.80 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.82 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.77 | ||

| 86 | G11–G18 | 3.40 | 29.654 |

| G19–G111 | 1.88 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.79 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.78 | ||

| 87 | G11–G18 | 3.40 | 29.345 |

| G19–G111 | 1.95 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.74 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.80 | ||

| 88 | G11–G18 | 3.41 | 29.223 |

| G19–G111 | 1.98 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.77 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.81 | ||

| 89 | G11–G18 | 3.42 | 29.101 |

| G19–G111 | 2.00 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.85 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.83 | ||

| 90 | G11–G18 | 3.42 | 28.765 |

| G19–G111 | 2.01 | ||

| G112–G117 | 4.93 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.86 | ||

| 91 | G11–G18 | 3.42 | 28.469 |

| G19–G114 | 3.53 | ||

| G115–G117 | 4.00 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.89 | ||

| 92 | G11–G18 | 3.40 | 28.324 |

| G19–G114 | 3.63 | ||

| G115–G117 | 4.01 | ||

| G118–G120 | 4.94 | ||

| 93 | G11–G18 | 3.37 | 28.208 |

| G19–G114 | 3.70 | ||

| G115–G117 | 4.01 | ||

| G118–G120 | 5.01 | ||

| 94 | G11–G18 | 3.33 | 28.134 |

| G19–G114 | 3.75 | ||

| G115–G117 | 4.00 | ||

| G118–G120 | 5.08 | ||

| 95 | G11–G18 | 3.31 | 28.130 |

| G19–G114 | 3.84 | ||

| G115–G117 | 3.99 | ||

| G118–G120 | 5.14 | ||

| 96 | G11–G18 | 3.30 | 28.120 |

| G19–G114 | 3.97 | ||

| G115–G117 | 3.99 | ||

| G118–G120 | 5.17 | ||

| 97 | G11–G18 | 3.28 | 28.100 |

| G19–G114 | 4.12 | ||

| G115–G117 | 4.04 | ||

| G118–G120 | 5.20 |

Appendix B

| Initial Investment | Operation and Maintenance Costs (Project Operating Cycle of 20 Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layered Water Injection System Device | Software Development Cost | System Integration and Adjustment | Data Monitoring and Analysis | Equipment Maintenance and Updates | Total Annual Operating Costs |

| CNY 500,000 per well | CNY 500,000 | CNY 200,000 | CNY 200,000 per year | CNY 100,000 per year | CNY 300,000 per year |

| Oil price | Discount rate | Management fee | Safety production cost | ||

| 2969 CNY/ton | 8% | 400 CNY/ton | 20 CNY/ton | ||

References

- Wang, D.; Liu, F.; Li, G.; He, S.; Song, K.; Zhang, J. Characterization and Dynamic Adjustment of the Flow Field during the Late Stage of Waterflooding in Strongly Heterogeneous Reservoirs. Energies 2023, 16, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.G. Wettability Literature Survey Part 5: The Effects of Wettability on Relative Permeability. J. Pet. Technol. 1987, 39, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Qiao, X.; Teng, W.; Xu, J.; Sun, S.; Xie, L. Impact of physical properties time variation on waterflooding reservoir development. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2016, 23, 768–771. Available online: https://www.dkyqt.com/#/digest?ArticleID=3774 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Spooner, V.E.; Geiger, S.; Arnold, D. Dual-porosity flow diagnostics for spontaneous imbibition in naturally fractured reservoirs. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR027775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, S.; Sebastian, G.; Arnold, D. Ranking Fractured Reservoir Models Using Flow Diagnostics. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference, Galveston, TX, USA, 10–12 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B.J.; Sech, R.P. Quantifying Impacts of Fluvial Intra-Channel-Belt Heterogeneity on Reservoir Behaviour. In Fluvial Meanders and Their Sedimentary Products in the Rock Record; Ghinassi, M., Colombera, L., Mountney, N.P., Reesink, A.J.H., Bateman, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.O.; Kuppe, F.; Chugh, S.; Bora, R.; Stojanovic, S.; Batycky, R. Full-Field Modeling Using Streamline-Based Simulation: Four Case Studies. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2002, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta-Gupta, A. Streamline Simulation: A Technology Update (includes associated papers 71204 and 71764). J. Pet. Technol. 2000, 52, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batycky, R.P.; Thiele, M.R. Technology Update: Mature Flood Surveillance Using Streamlines. J. Pet. Technol. 2016, 68, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Park, J.; Datta-Gupta, A.; Shekhar, S.; Grover, K.; Das, J.; Shankar, V.; Kumar, M.S.; Chitale, A. Improving Polymerflood Performance Via Streamline-Based Rate Optimization: Mangala Field, India. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Virtual, 31 August–4 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, M.R.; Batycky, R.P. Using Streamline-Derived Injection Efficiencies for Improved Waterflood Management. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2006, 9, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Deng, L. Water flooding flowing area identification for oil reservoirs based on the method of streamline clustering artificial intelligence. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Onishi, T.; Kam, D.; Dehghani, K.; Wen, X.-H. Application of Combined Streamline Based Reduced-Physics Surrogate and Response Surface Method for Field Development Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 13–15 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Kong, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C. Numerical Simulation Study on Factors Affecting Water-Flooding Efficiency. Contemp. Chem. Ind. 2016, 45, 1640–1642+1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Study on Numerical Simulation of Reservoir Fine Water Injection Development Considering Reservoir Heterogeneity. Int. J. Energy 2025, 6, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, D.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhen, K. The Full-Automatic Real-Time Display, Testing and Adjustable System in Separated Layers Water Injection Well. In Proceedings of the SPE Intelligent Energy International, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 27–29 March 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Jia, D.; Yu, J.; Pei, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, L.; Shujun, B.A. Separate Layer Water Injection for Offshore Directional Wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil & Gas Conference and Exhibition, Perth, Australia, 25–27 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhou, H.; Feng, G.; Huo, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, X.; Liu, B.; et al. Application of Remote Monitoring and Controlling Intelligent Separated Layer Water Injection Technology in BQ Oilfield, Dagang. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 12–14 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, E.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, H.; Dong, C.; Du, Q.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhu, J. A New Method for Optimizing Water-Flooding Strategies in Multi-Layer Sandstone Reservoirs. Energies 2024, 17, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q. Variation law and microscopic mechanism of reservoir permeability in sandstone oilfields by long-term water flooding. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xu, R.; Fu, C.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Z. Multi-level fuzzy identification method for interwell thief zone. Lithol. Reserv. 2018, 30, 105–112. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=7DUETwKSFy4IBT6fyDUNF-ezFTCv1Q4kKtXjUwyzQwvMy-kFJ6CQ0NQ-OvIKDSo29Umz4uW_lDZD34FOa_eleq65k_1wlgKiircCj18v-uFeB9mxz-O3tB2HdKsSR3u-eUJMOylcbnUqTO4K1mq185dnMoxFVkbe7xQTKrl0q-5ELEGN43Kv1g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Shan, G.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Guo, J. Water Injection Adjustment Method Based on Dynamic Flow Resistance. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2023, 44, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Peng, B. Classification and Management Method for Non-productive Circulation Based on Seepage Resistance. Xi’an Petroleum University, Shaanxi Petroleum Society. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Oil and Gas Field Exploration and Development; Geological Brigade, Fourth Oil Production Plant, Daqing Oilfield, Xian, China, 16–18 October 2019; pp. 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Yin, R.; Gao, N.; Sheng, H.; Gao, Z. Establishment and Application of a New Analytical Fractional Flow Equation. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2021, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, P.; Ren, Y.; Yin, Y.; Xing, C.; Lu, X. Optimization of Water Injection Pressure for Water-Flood Development in Offshore Oilfields. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2021, 42, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Seepage Resistance, mPa·s·mD−1·m−1 | Layer | Seepage Resistance, mPa·s·mD−1·m−1 | Layer | Seepage Resistance, mPa·s·mD−1·m−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G11 | 12.51 | G110 | 5.34 | G116 | 1.13 |

| G12+3 | 7.11 | G111 | 2.61 | G117 | 0.31 |

| G14+5 | 4.05 | G112 | 1.22 | G118 | 1.50 |

| G16+7 | 6.19 | G113 | 1.42 | G119 | 0.34 |

| G18 | 8.47 | G114 | 1.45 | G120 | 0.62 |

| G19 | 2.92 | G115 | 0.52 | / | / |

| Seepage Resistance Zone (mPa·s·mD−1·m−1) | Number of Floors | Sandstone Thickness (m) | Effective Thickness (m) | Sandstone Water Absorption Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 12 | 14.79 | 5.91 | 35.67 |

| 5–10 | 4 | 6.42 | 3.49 | 30.89 |

| >10 | 1 | 1.37 | 0.71 | 23.6 |

| Total | 17 | 22.57 | 10.11 | 31.58 |

| Interlayer Seepage Resistance Gradient | Recovery Rate, % |

|---|---|

| 1.11 | 25.49 |

| 2.66 | 27.10 |

| 3.4 | 28.72 |

| 4.93 | 33.76 |

| 8.14 | 28.47 |

| 9 | 27.48 |

| 11.82 | 20.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, C.; Hui, W.; Shan, G.; Yang, E.; Qu, M.; Wang, H. Research on Dynamic Control Methods for Fine-Scale Water Injection Zones Based on Seepage Resistance. Processes 2025, 13, 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123966

Dong C, Hui W, Shan G, Yang E, Qu M, Wang H. Research on Dynamic Control Methods for Fine-Scale Water Injection Zones Based on Seepage Resistance. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123966

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Chi, Weiming Hui, Gaojun Shan, Erlong Yang, Ming Qu, and Hai Wang. 2025. "Research on Dynamic Control Methods for Fine-Scale Water Injection Zones Based on Seepage Resistance" Processes 13, no. 12: 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123966

APA StyleDong, C., Hui, W., Shan, G., Yang, E., Qu, M., & Wang, H. (2025). Research on Dynamic Control Methods for Fine-Scale Water Injection Zones Based on Seepage Resistance. Processes, 13(12), 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123966