Pressure Prediction and Application Considering Shale Weak Surface Effects and Anisotropic Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

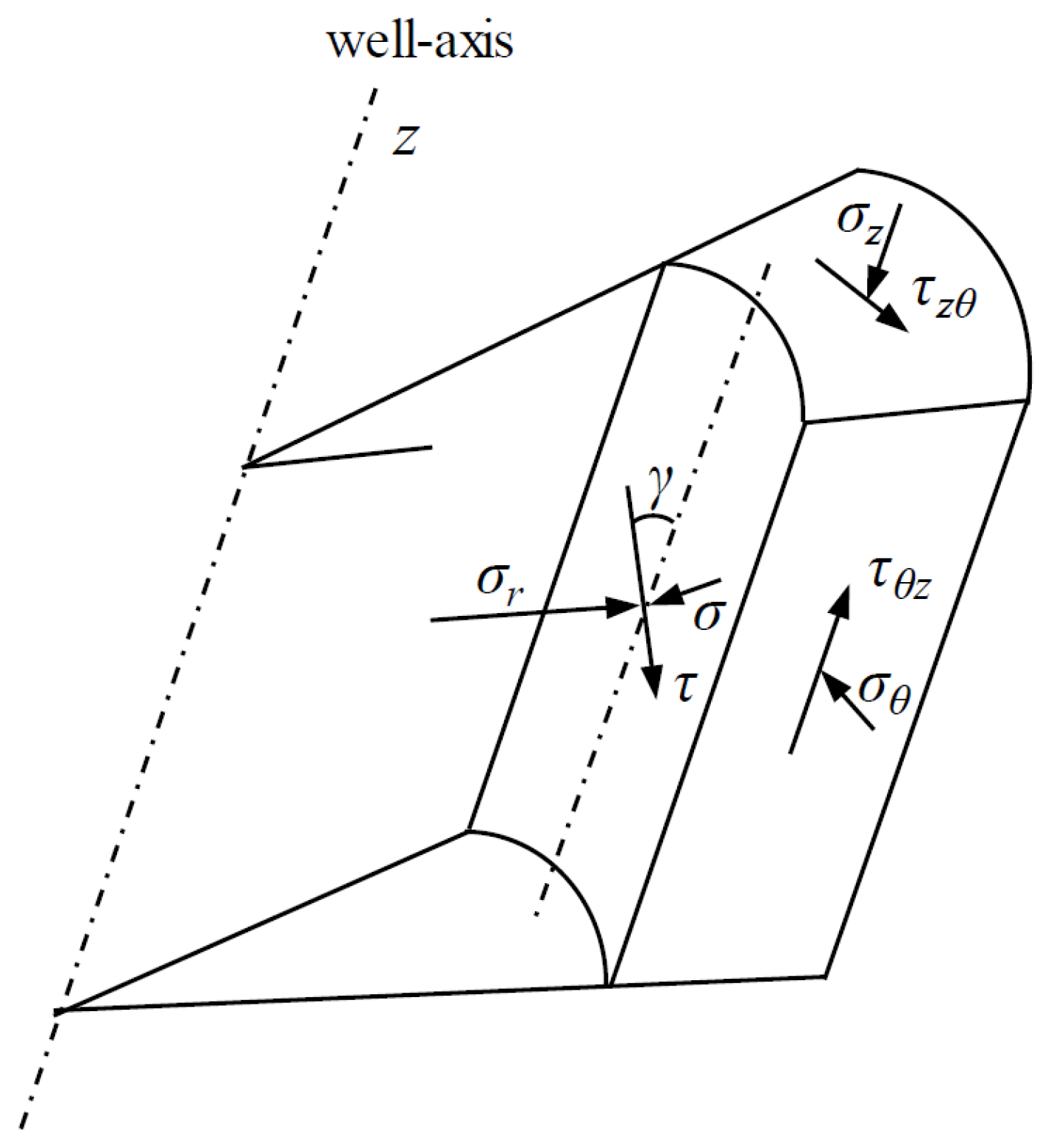

2. Prediction and Spatial Distribution of Seepage-Induced Stresses Around Wellbores in Shale Formations

2.1. Predictive Model for the Seepage-Induced Stress Field Around Wellbores in Shale Formations

- : wellbore pressure;

- : pore pressure;

- : the degree of pore pressure transmission at the wellbore wall, ;

- : no seepage (completely impermeable); : full penetration (completely permeable);

- : characterizes the choice of direction for injection/suction;

- : the seepage effect coefficient; ;

- : the Biot coefficient; : Poisson’s ratio.

- : the principal in situ stress coordinate system (the borehole axis is not necessarily aligned with this coordinate system);

- : the well inclination angle;

- : the well azimuth angle; (relative to the ): the circumferential angle along the wellbore wall.

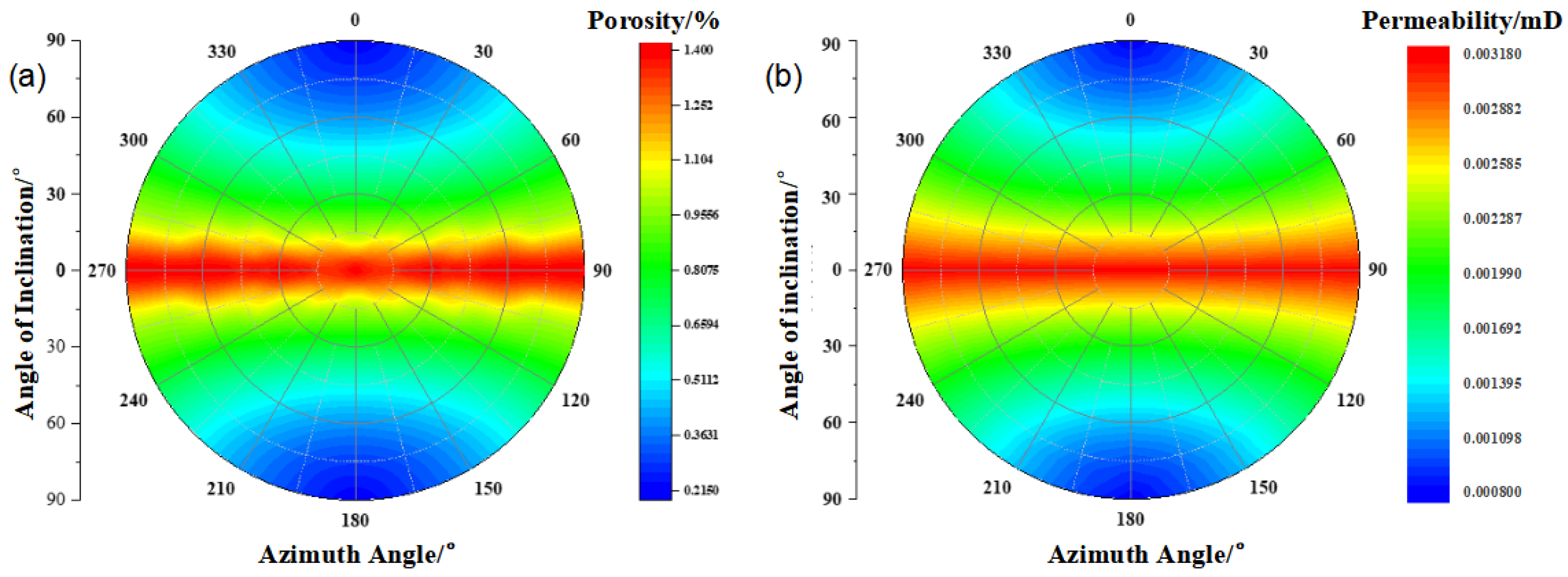

2.2. Distribution Characteristics of the Seepage-Induced Stress Field Around Wellbores in Shale Formations

- : the matrix permeability;

- : the aperture of the ith group of fractures;

- : the fracture spacing;

- : the unit vector of the fracture orientation.

3. Prediction and Evaluation of Collapse Pressure for Horizontal Wells in Shale Formations

3.1. Predictive Model for Collapse Pressure in Horizontal Wells in Shale Formations

- C0: the intact rock cohesion, MPa;

- Cw: the bedding plane cohesion, MPa;

- : the internal friction angle of the intact rock, °;

- : the internal friction angle of the bedding plane, °;

- : the angle between the fracture plane normal and the principal stress, °;

- : the cohesion indicator function primarily governed by the intact rock cohesion and the bedding plane cohesion;

- : the friction coefficient indicator function governed by the internal friction angle of the intact rock and the internal friction angle of the bedding plane.

- : the maximum principal stress, MPa;

- : the intermediate principal stress, MPa;

- : the minimum principal stress, MPa.

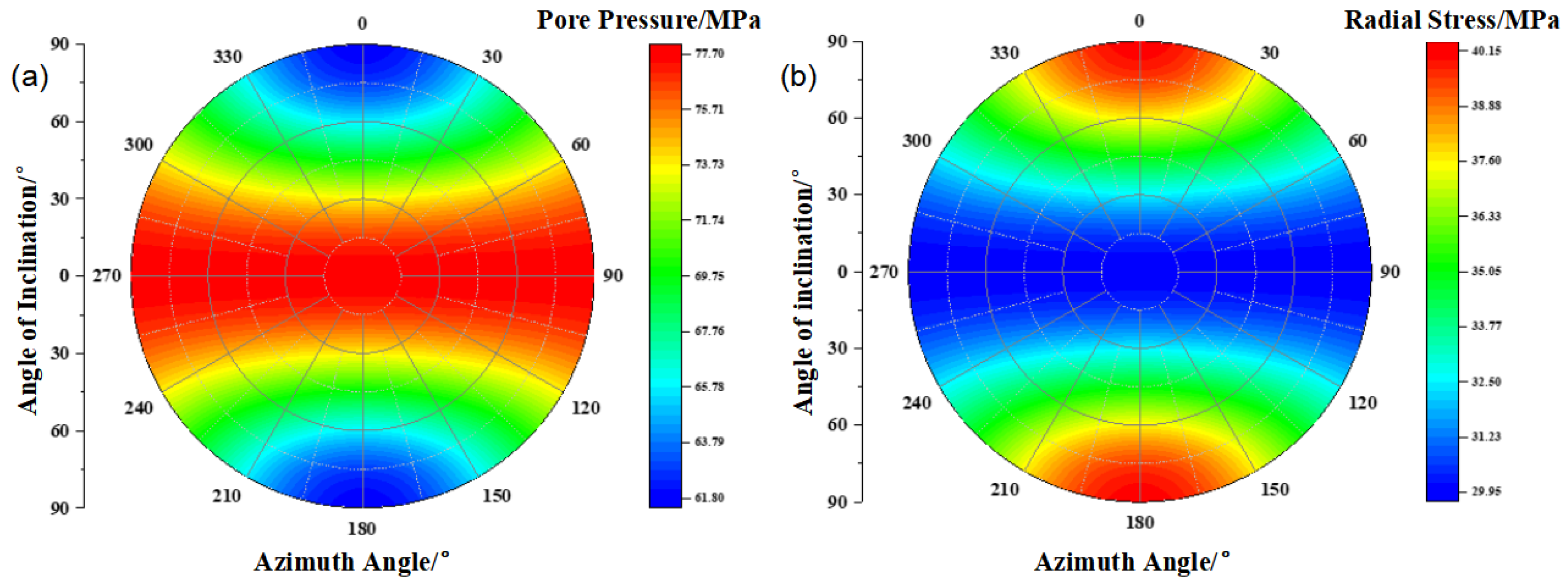

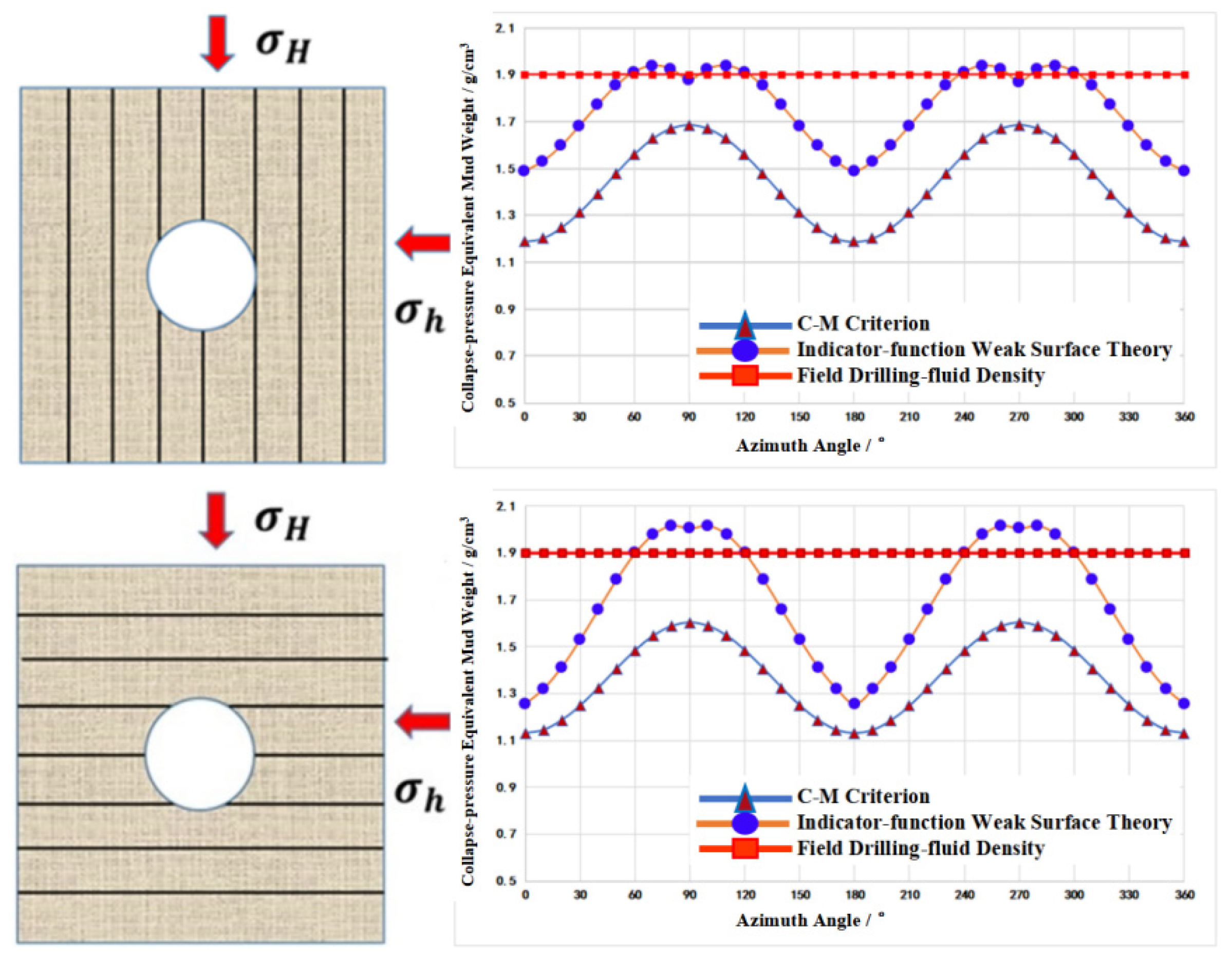

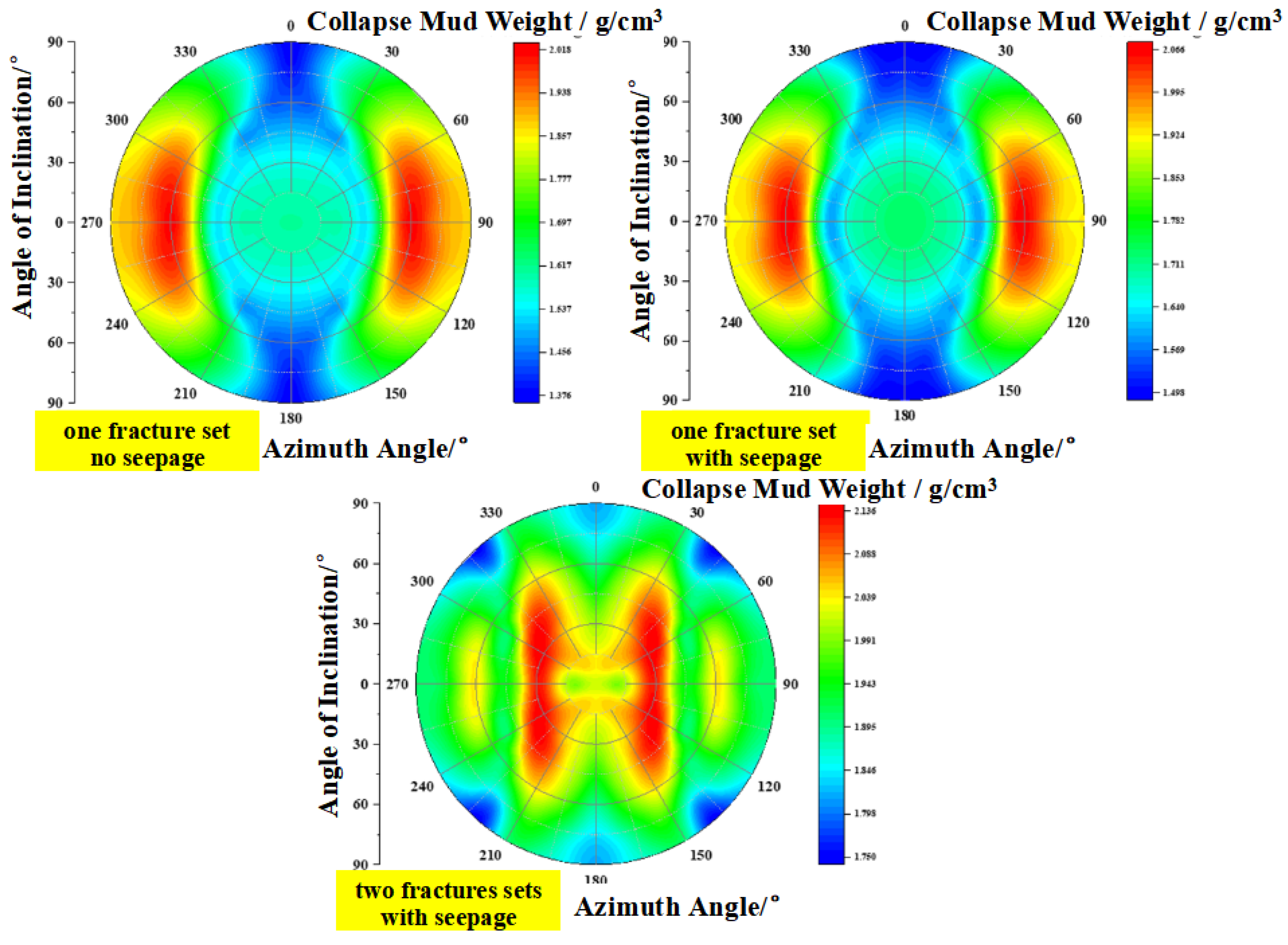

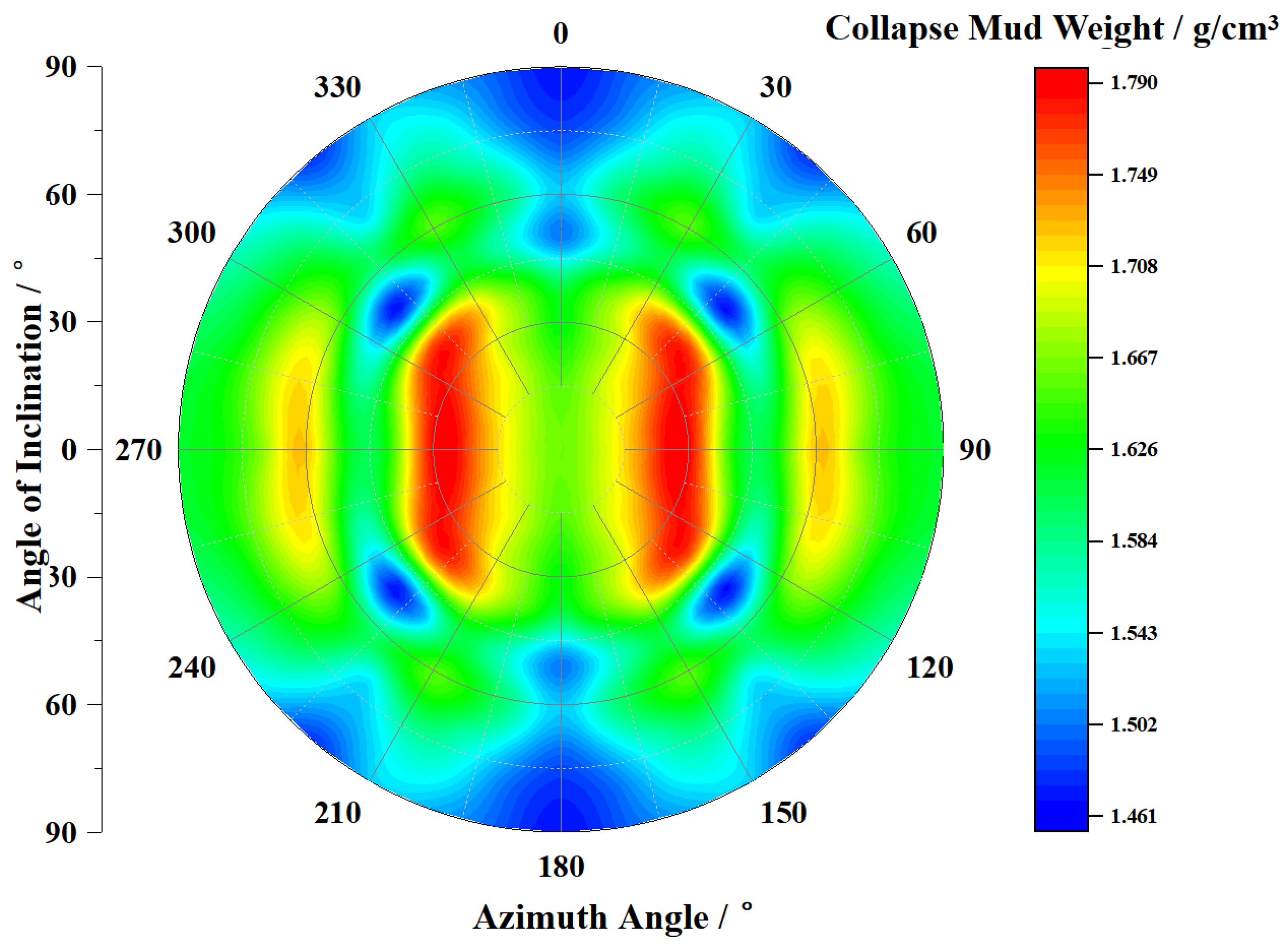

3.2. Evaluation of Wellbore Stability for Horizontal Wells in Shale Formations

4. Prediction of the Safe Mud Weight Window for Horizontal Wells in Shale Formations

4.1. Predictive Model for Pore Pressure in Shale Formations

- (1)

- Eaton Method

- Pp: the formation pore pressure, g/cm3;

- : the sonic slowness, ;

- Rt: the electrical resistivity, ;Ppn: the pore fluid pressure, MPa;

- : the overburden stress, MPa.

- (2)

- Bowers Method

- Vp: the acoustic velocity, fts;

- : the vertical effective stress, MPa;

- A: the empirical coefficient.

4.2. Predictive Model for Fracture Pressure in Shale Formations

- Pf: the formation fracture pressure, MPa;

- St: the tensile strength of the rock, MPa;

- : Poisson’s ratio.

5. Field Application

5.1. Wellbore Stability Prediction

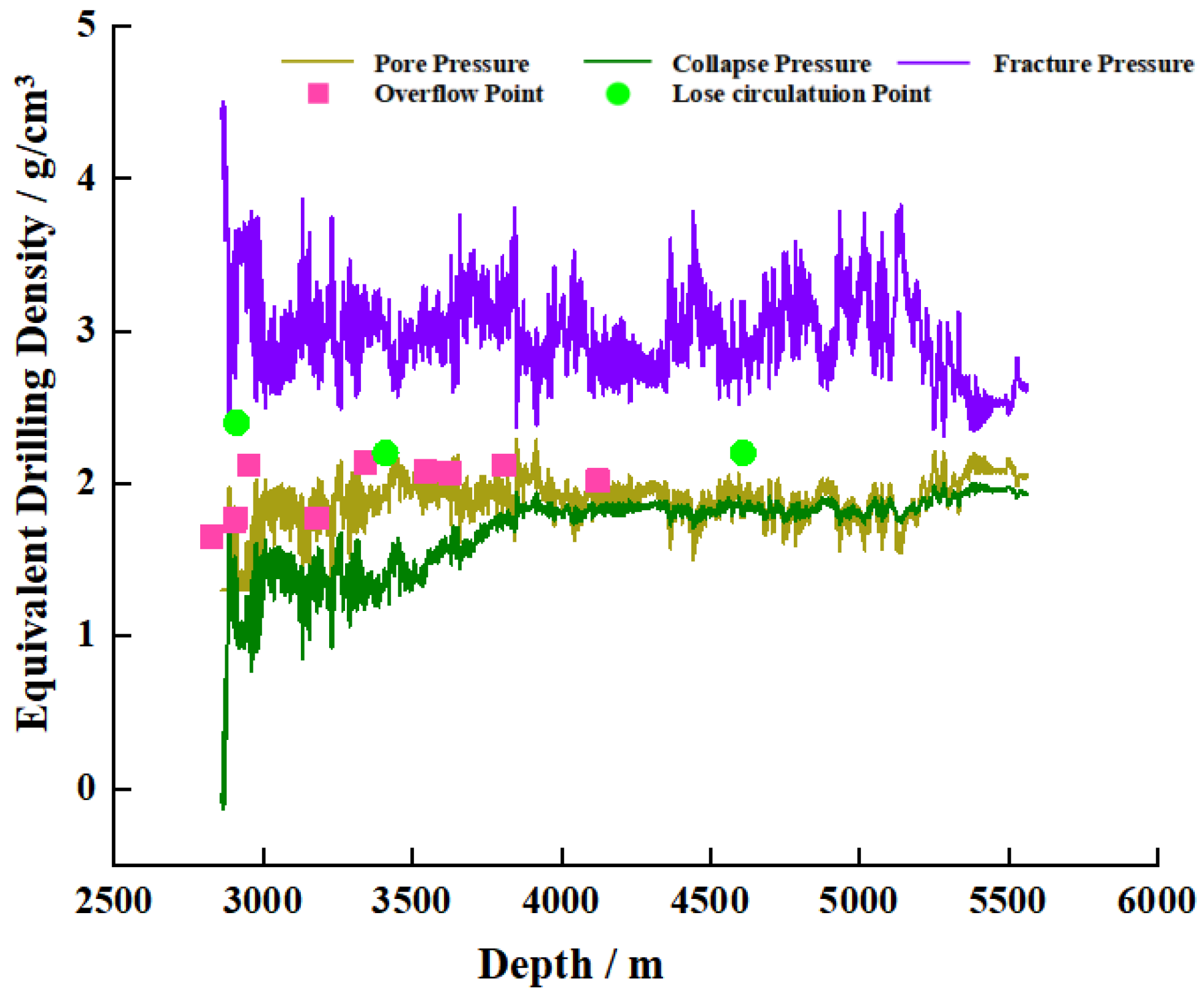

5.2. Prediction of the Safe Mud Weight Window

6. Conclusions and Insights

- (1)

- Under positive pressure differential across the wellbore, drilling fluid seepage, and pressure penetration alter the formation pore pressure and the radial stress at the wellbore wall, thereby affecting wellbore stability. Variations in borehole trajectory, the weak surface effect of bedding fractures, the degree of fracture development, drilling fluid seepage, and pressure penetration effects all influence the formation collapse pressure.

- (2)

- The collapse pressure for shale reservoirs with bedding-related fractures was predicted using the H–B criterion, the M-C criterion, and a weak surface theory augmented with an indicator function. Comparative analysis against laboratory data shows that the indicator function weak surface approach yields more accurate collapse pressure predictions, providing practical guidance for addressing wellbore stability issues in shale reservoirs.

- (3)

- Formation pore pressure and fracture pressure prediction models suitable for southern Sichuan shales were selected, leading to a method for determining the safe mud weight window for shale gas horizontal wells in this area. Comparison of the three pressure prediction results with field measurements verifies the applicability and reliability of the models.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nekwaya, T.T. Wellbore Stability Analysis Using Logging Data: A Case Study For Z-Block, Jiyang Depression. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Jin, Y. Research progress and development trend of deep well wall stabilization technology. Oil Drill. Technol. 2005, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Liang, L. Research on fabric characteristics and borehole instability mechanisms of fractured igneous rocks. Pet. Sci. 2013, 10, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Atkinson, C.; Bradford, I. Effect of Inhomogeneous Rock Properties on the Stability of Wellbores. In Proceedings of the IUTAM Symposium on Analytical and Computational Fracture Mechanics of Non-Homogeneous Materials, Cardiff, UK, 18–22 June 2002; Springer: Dodrecht, The Netherlands; Volume 97, pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ouadfeul, S.-a.; Aliouane, L. Wellbore Stability in ShaleGas Reservoirs, A Case Study fromThe Barnett Shale. In Proceedings of the SPE International Conference and Exhibition on Formation Damage Control, Lafayette, LA, USA, 24–26 February 2015. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Han, T.; Pervukhina, M.; Ben Clennell, M.; Neil Dewhurst, D. Model-based pore-pressure prediction in shales: An example from the Gulf of Mexico, North America. Geophysics 2017, 82, M37–M42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; Chen, M.; Yuan, J.B.; Jin, Y.; Teng, X.Q. Mechanism of well wall destabilization in inclined wells in anisotropic formations. J. Pet. 2013, 3, 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.F.; Liu, H.B.; Yu, A.R.; Chen, S.H.; Wang, X.H.; Chen, H.J. Study on wall stability of barehole completion in deep brittle shale horizontal wells. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 41, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.B.; Liu, H.B.; Zhang, J.T.; Shi, J.; Wang, Z.H. Mechanical properties of deep brittle shale and well wall stability. Spec. Reserv. 2020, 27, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.B.; Liang, K.; Wang, C.H.; Li, J.J.; Chen, X.P. Mechanism of well wall destabilization in anisotropic layered rational shale. Contemp. Chem. Ind. 2022, 51, 550–554. [Google Scholar]

- See, H.; Jean, C. Fracture Initiation from Inclined Wellbores in Anisotropic Formations. J. Pet. Technol. 1996, 48, 612, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, W.H.; Liu, P.; Wen, R.; Gou, Q.Y.; Li, Q.S.; Xu, E.S.; Ling, W.T.; Huang, Y.J.; Ren, X.X.; Yu, T.; et al. Digital Pore Pressure Prediction for Well Drilling Using Machine Learning in a Deep Shale Gas Field. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Asia Pacific Drilling Technology Conference and Exhibition, Bangkok, Thailand, 7–8 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sone, H.; Zoback, M.D. Mechanical properties of shale-gas reservoir rocks-Part 1: Static and dynamic elastic properties and anisotropy. Geophysics 2013, 78, D381–D392. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Deng, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, M.W.; Wang, Y.K. Calculation method of wall collapse pressure in directional wells in anisotropic formations. Broken Block Oil Gas Field 2010, 17, 608–610. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.B.; Zhang, F.; Meng, Y.F.; Chen, S.H.; He, H.; Wu, N. Experimental study on wall stability of horizontally drilled shale gas wells in Jiao Shi Ba area. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2017, 13, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Ren, T.; Yin, Z.B.; Lu, Z.Y.; Wang, Q. Mechanism of well wall stability in fractured formations of the Junggar South Margin Alluvial Zone. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 45, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.H.; Song, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhuo, L.B.; Hao, C.; Feng, F.P.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. The invasion law of drilling fluid along bedding fractures of shale. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, H.; Pan, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W. Matrix permeability anisotropy of organic-rich marine shales and its geological implications: Experimental measurements and microscopic analyses. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 281, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y. Pore Structure and Migration Ability of Deep Shale Reservoirs in the Southern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2024, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halakatevakis, N.; Sofianos, A.I. Correlation of the Hoek–Brown failure criterion for a sparsely jointed rock mass with an extended plane of weakness theory. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 1166–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, D.; Zuo, B.K. Reservoir Geomechanics; Shi, L.; Chen, Z.W.; Liu, Y.S.; Wang, J.S.; Xu, M.S.; Jian, Z., Translators; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.M.; Zhang, H.X.; Hou, Q.L.; Zhao, B.; Hu, D.Y.; Huang, Y.Z. Generalized rupture activity criterion. J. Geomech. 2024, 30, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, H.; Tsiambaos, G. A modified Hoek–Brown failure criterion for anisotropic intact rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2008, 45, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Jiang, X.X.; Zhu, Z.D.; Shi, F.J.; Ge, Z.L. Investigation of rock damage constitutive model based on Hoek-Brown criterion and its parameterization. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2011, 30, 2647–2652. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K.; Pietruszczak, S. Application of critical plane approach to the prediction of strength anisotropy in transversely isotropic rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2008, 45, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqun, L.; Haibo, L.; Junru, L. Study on strength characteristics of slates based on Hoek-Brown criterion. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2009, 28, 3452–3457. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.Q.; Zhang, C.S.; Wang, W. An improved anisotropic Hoek-Brown strength criterion. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2018, 37, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, B.A. The effect of overburden stress on geopressure prediction from well logs. J. Pet. Technol. 1972, 24, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.Q.; Wang, H.W.; Zhao, H. Logging study on geophysical modeling of shale gas horizontal well precursors. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, G.L. Pore pressure estimation from velocity data: Accounting for overpressure mechanisms besides undercompaction. SPE Drill. Complet. 1995, 10, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, C.; Yang, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Xin, Q.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X. Pressure Prediction and Application Considering Shale Weak Surface Effects and Anisotropic Characteristics. Processes 2025, 13, 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123889

Gong C, Yang L, Ouyang Y, Xin Q, Li Z, Teng Y, Zhang P, Xu X, Zhang X. Pressure Prediction and Application Considering Shale Weak Surface Effects and Anisotropic Characteristics. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123889

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Chenxing, Le Yang, Yong Ouyang, Qingqing Xin, Zhijun Li, Yuxiang Teng, Pengxin Zhang, Xiaoyue Xu, and Xiuling Zhang. 2025. "Pressure Prediction and Application Considering Shale Weak Surface Effects and Anisotropic Characteristics" Processes 13, no. 12: 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123889

APA StyleGong, C., Yang, L., Ouyang, Y., Xin, Q., Li, Z., Teng, Y., Zhang, P., Xu, X., & Zhang, X. (2025). Pressure Prediction and Application Considering Shale Weak Surface Effects and Anisotropic Characteristics. Processes, 13(12), 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123889