Technical and Economic Analysis of Rural Hydrogen–Electricity Microgrids

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Gaps

1.4. Contributions

- (1)

- This is the first time that a comprehensive technical and economic analysis of rural electric–hydrogen microgrids under different time periods and technology combinations has been conducted, providing more targeted technology selection criteria for rural areas with varying resource conditions and grid connection capabilities.

- (2)

- A complete planning model for rural microgrids, including hydrogen energy storage and electrical energy storage, is established. Typical days are selected using the K-means algorithm, and the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) is employed as the key indicator. The wind and solar curtailment rate and self-balancing rate are evaluation indicators to construct a techno-economic evaluation system for rural microgrids.

- (3)

- A comparative analysis of different off-grid energy storage, different main grid access methods, and different hydrogen production methods in different time periods is constructed, and the following conclusions were drawn: compared with the pure electric energy storage, the LCOE when using electric-hydrogen hybrid energy storage in an off-grid state is reduced to 0.2824 CNY/kWh, a reduction of 33.06%; compared with now, the cost reduction of PEM in 2030 will reach 49.3%, and the LCOE of AWE will be 0.0004 ¥/kWh lower. In 2030, PEM will become the most preferred method of hydrogen production in rural electric–hydrogen microgrids.

1.5. Organization

2. Path Analysis of Rural Electricity–Hydrogen Coupled Microgrids

2.1. Comparison of Hydrogen Energy Storage Technologies

2.2. Technology Selection for Rural Electricity–Hydrogen Coupled Microgrids

3. Capacity Planning Model for Rural Electric–Hydrogen Microgrids

3.1. Objective Function

3.2. Constraints

3.2.1. Power Balance Constraints

3.2.2. Hydrogen Supply and Demand Balance Constraints

3.2.3. Hydrogen Energy Storage Operation Constraints

3.2.4. Battery Energy Storage Operation Constraints

3.2.5. Photovoltaic and Wind Power Generation Operation Constraints

3.2.6. Biomass Generation Operation Constraints

3.3. Evaluation Indicators

3.3.1. Wind and Solar Power Curtailment Rates

3.3.2. Self-Balancing Rate

4. Solution Method

4.1. Mathematical Definitions

4.1.1. Euclidean Distance

4.1.2. Distance Between a Data Point and a Clustering Center

4.1.3. Sum of Squared Error

4.2. Implementation Steps for Typical Day Selection in Four Seasons

5. Case Study

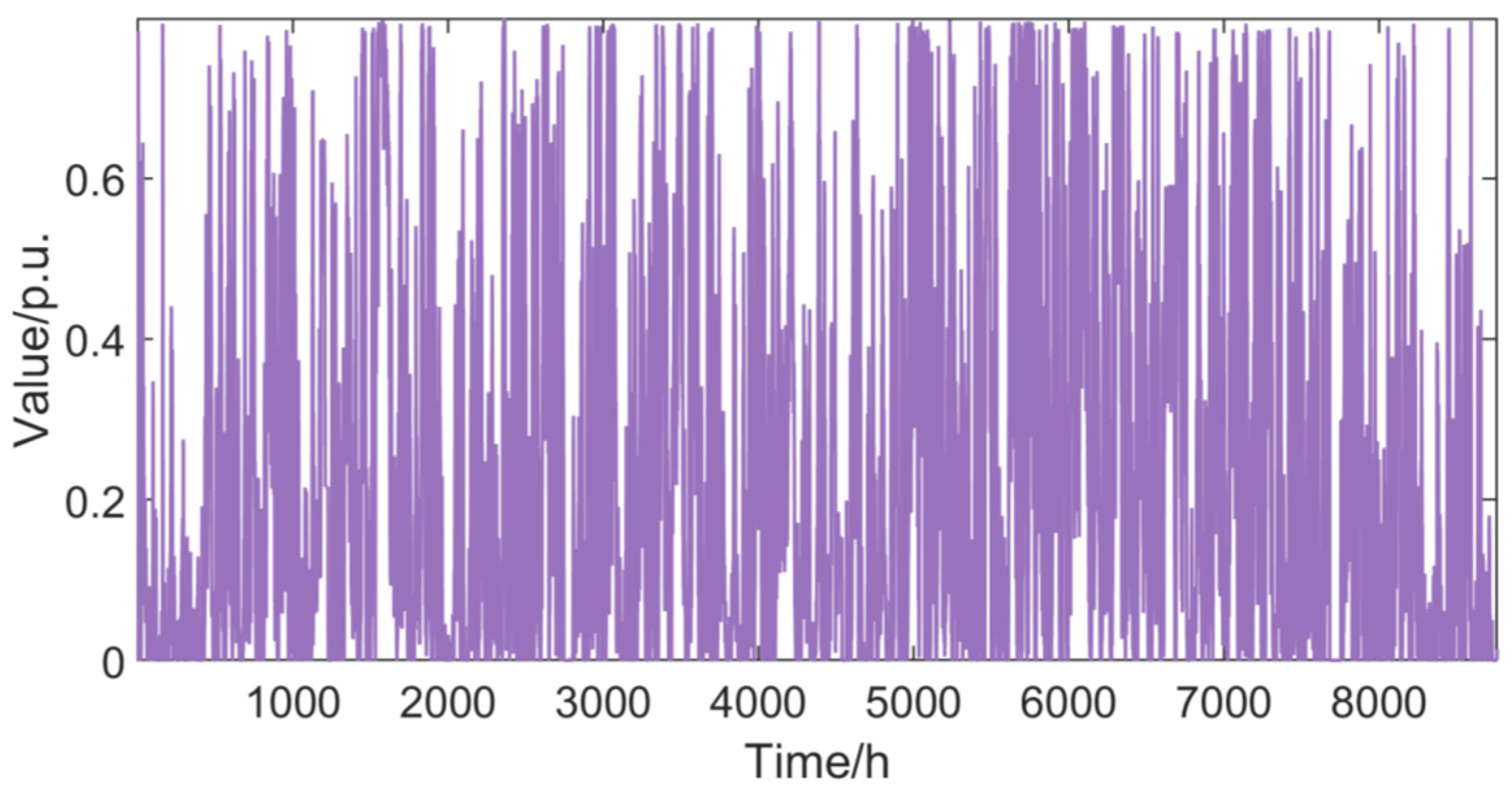

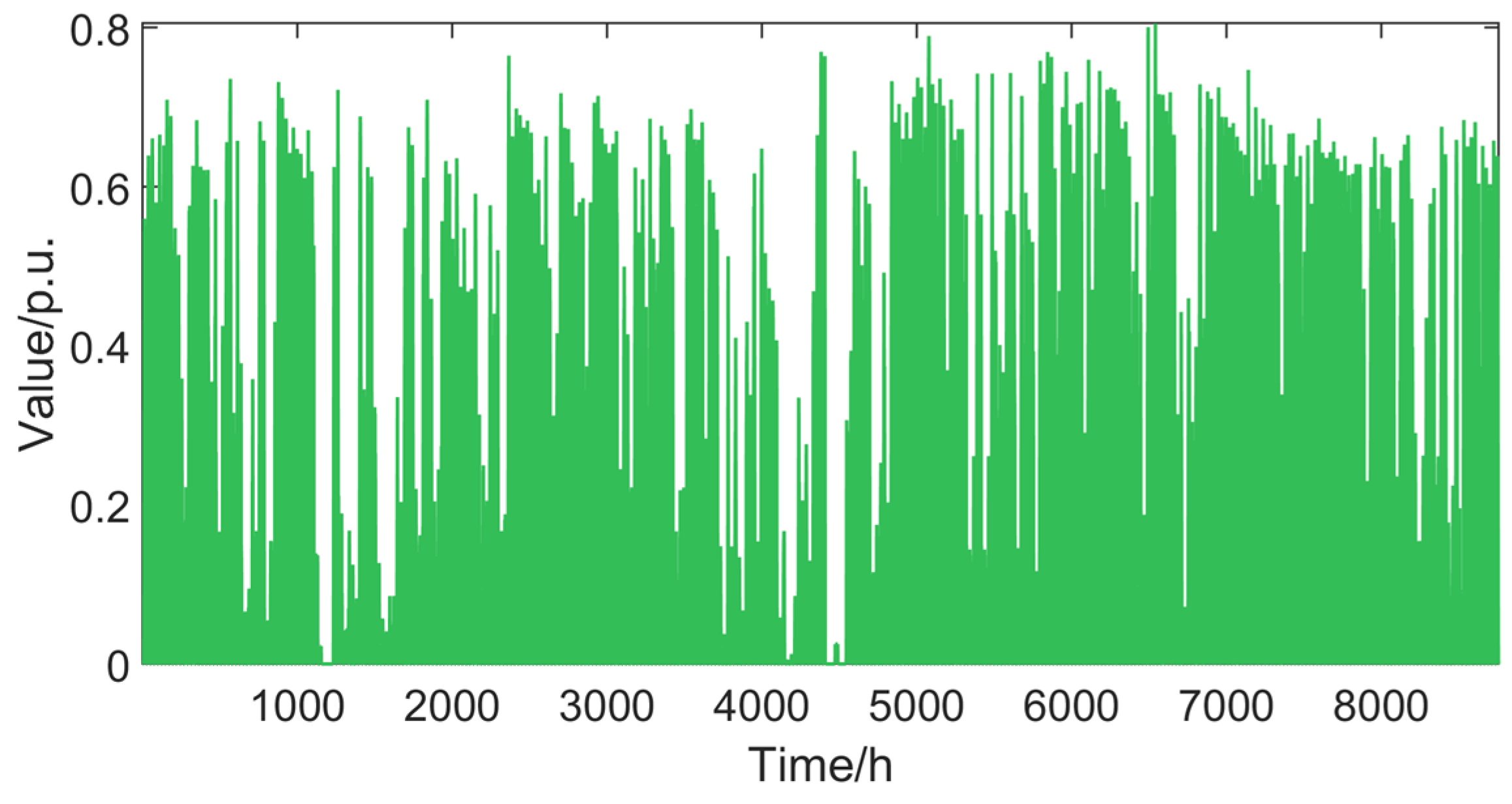

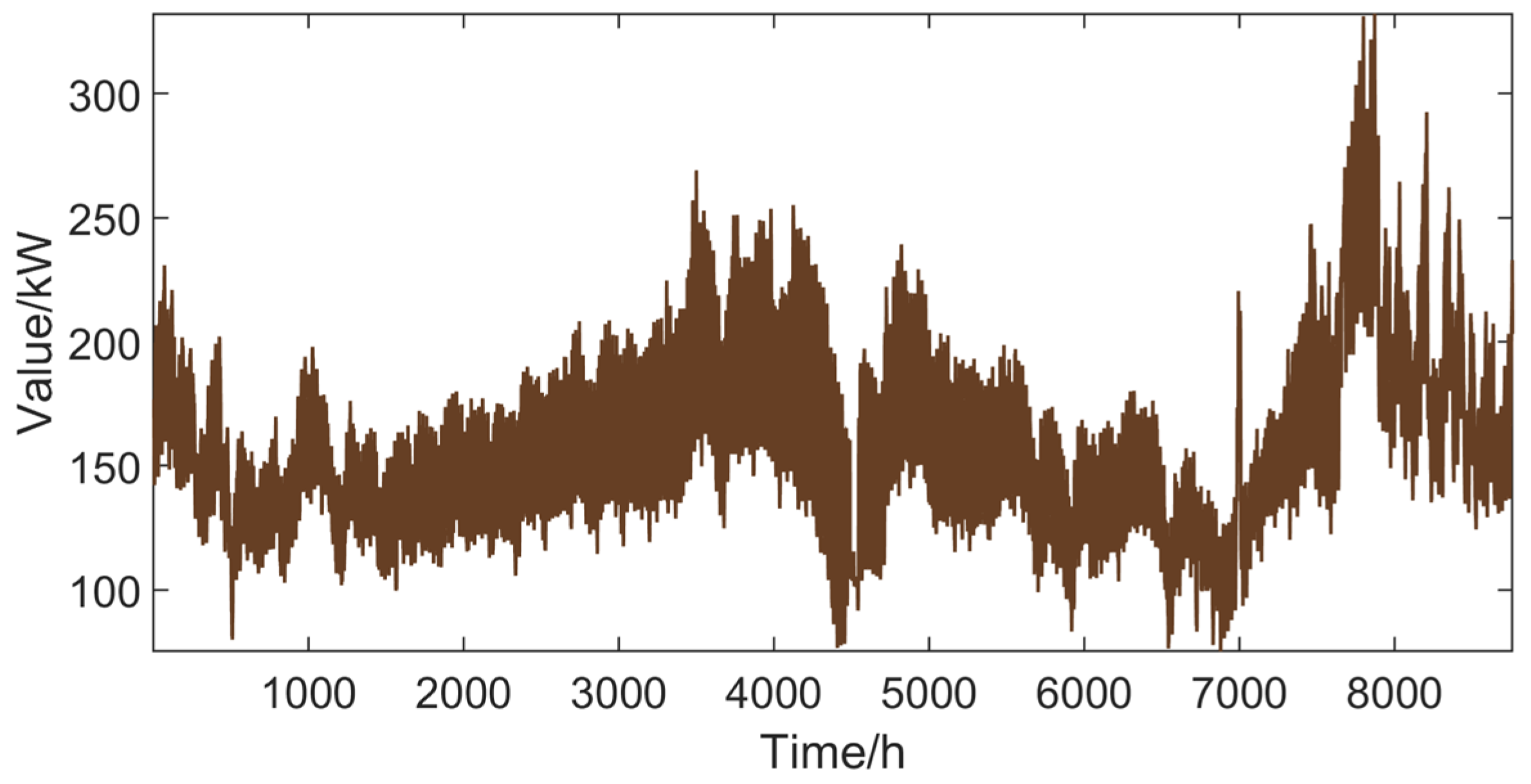

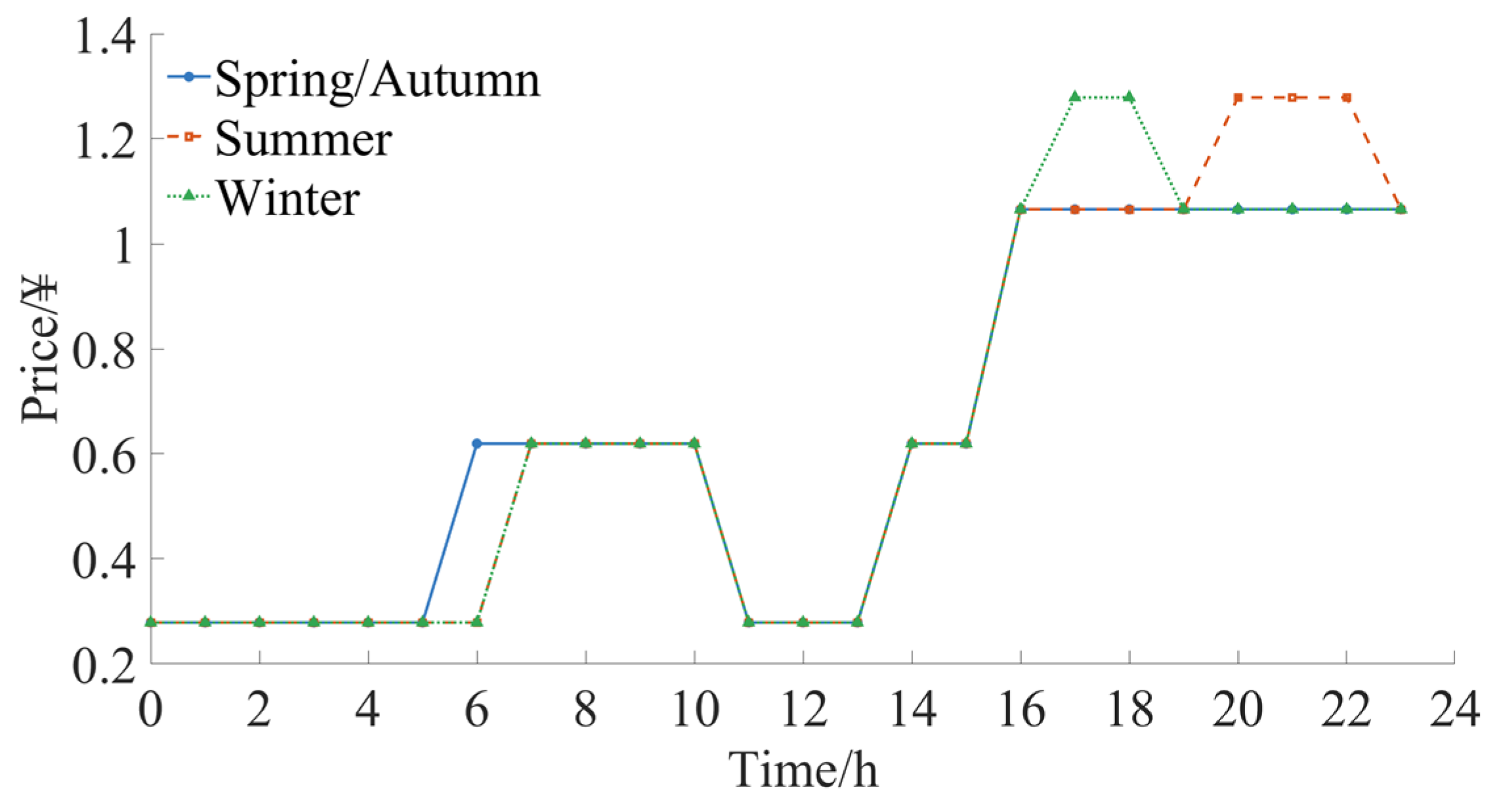

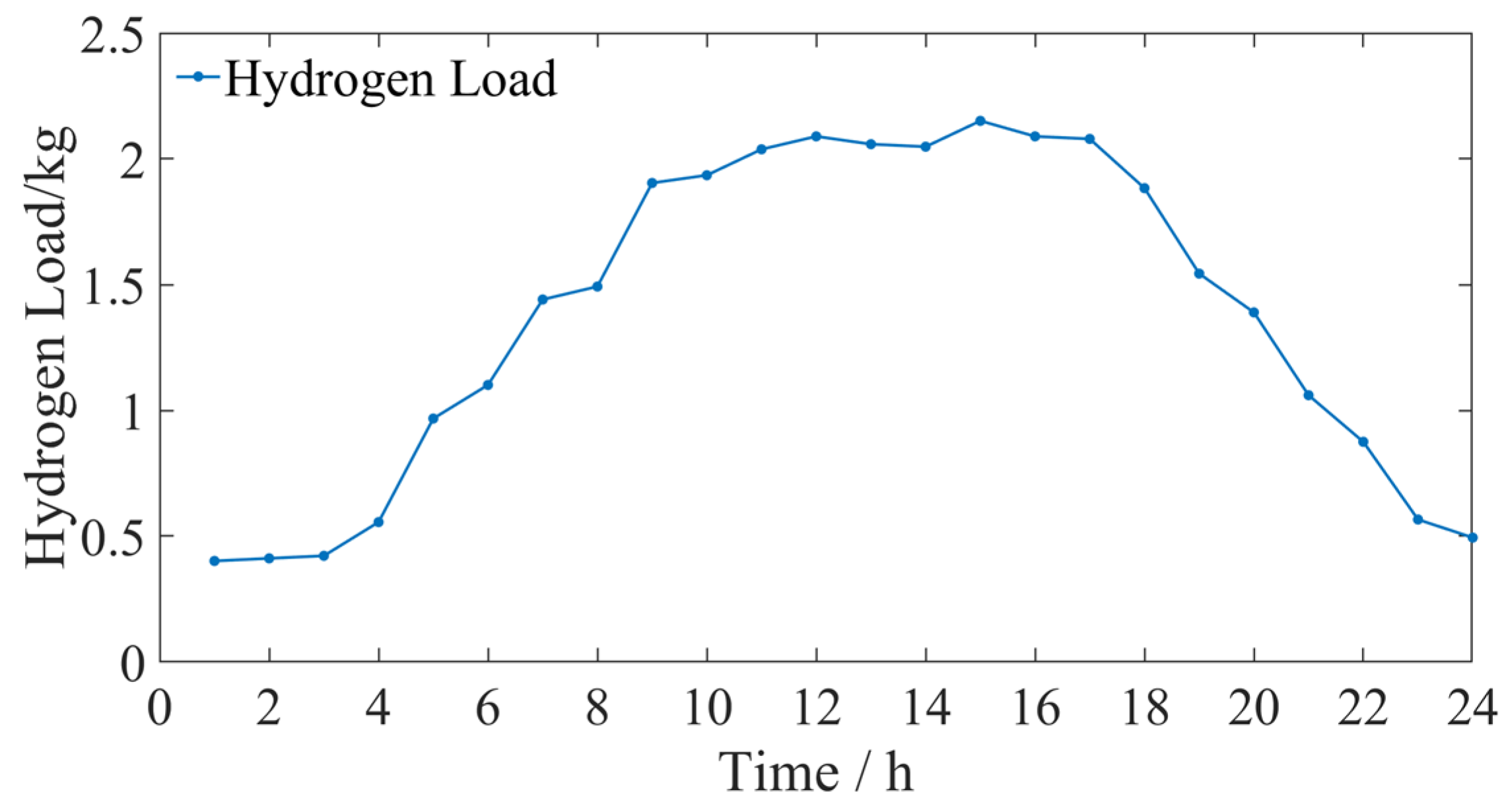

5.1. Data Description

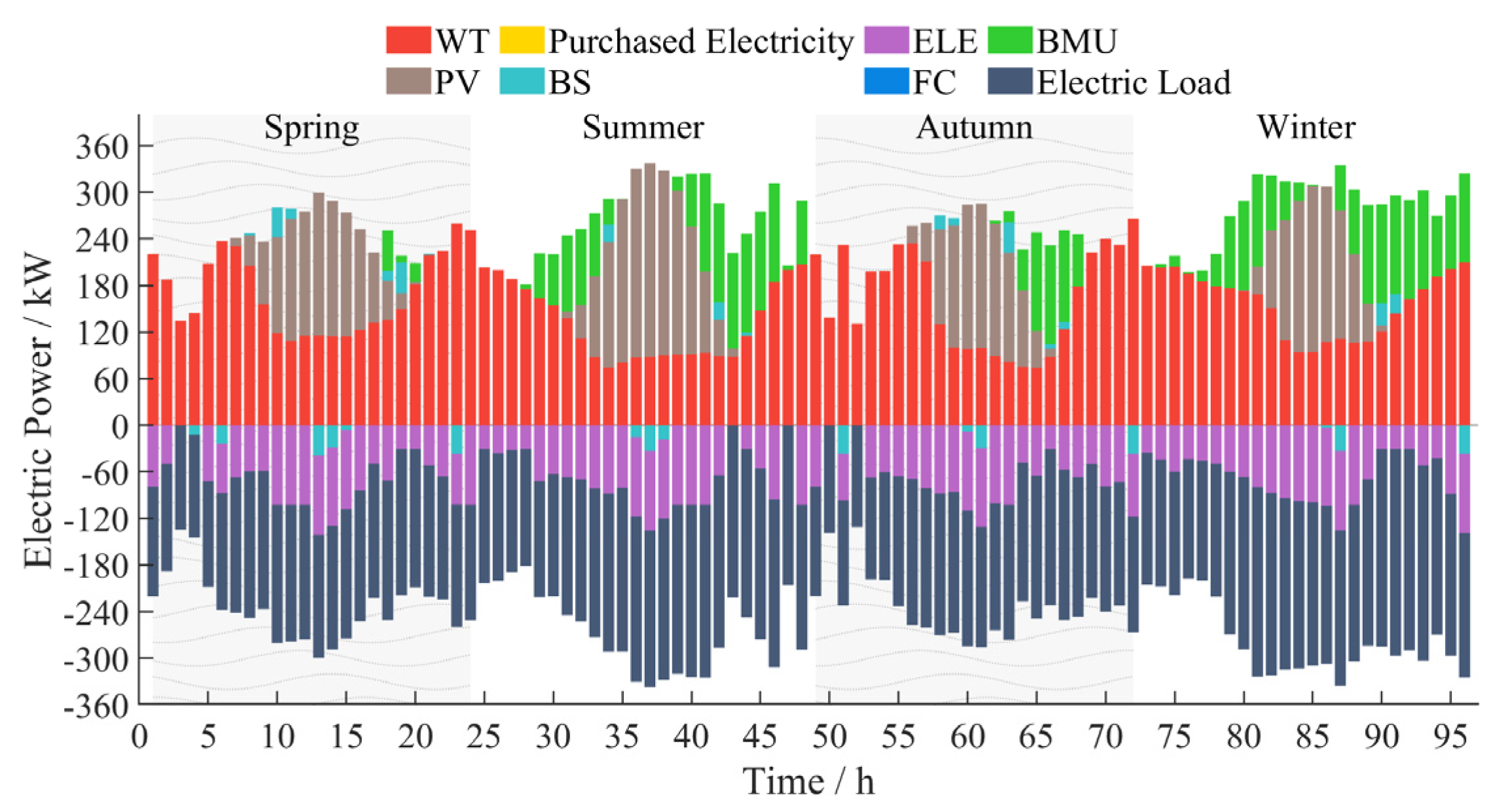

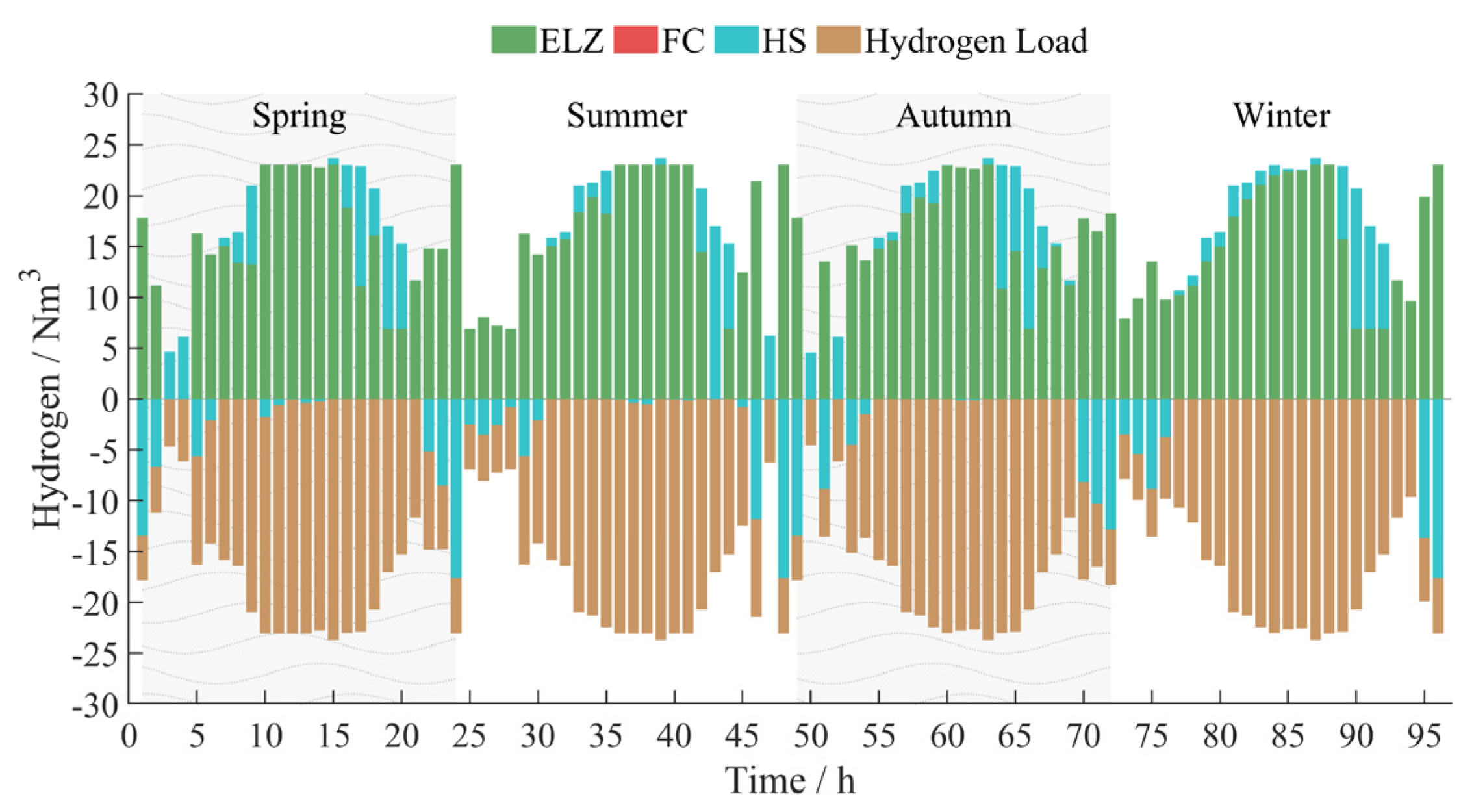

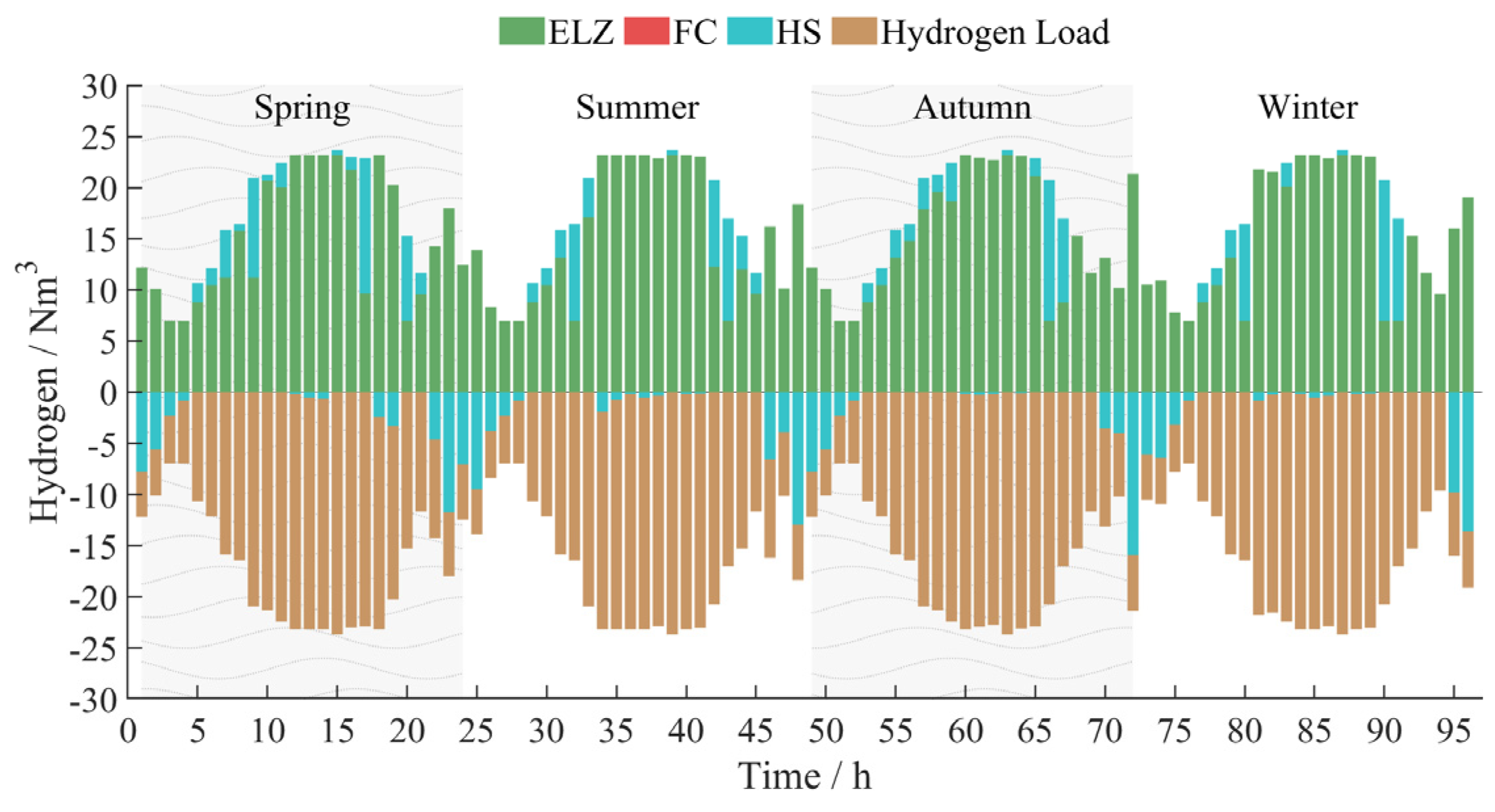

5.2. Technical and Economic Analysis of Energy Storage in Off-Grid Operation Mode

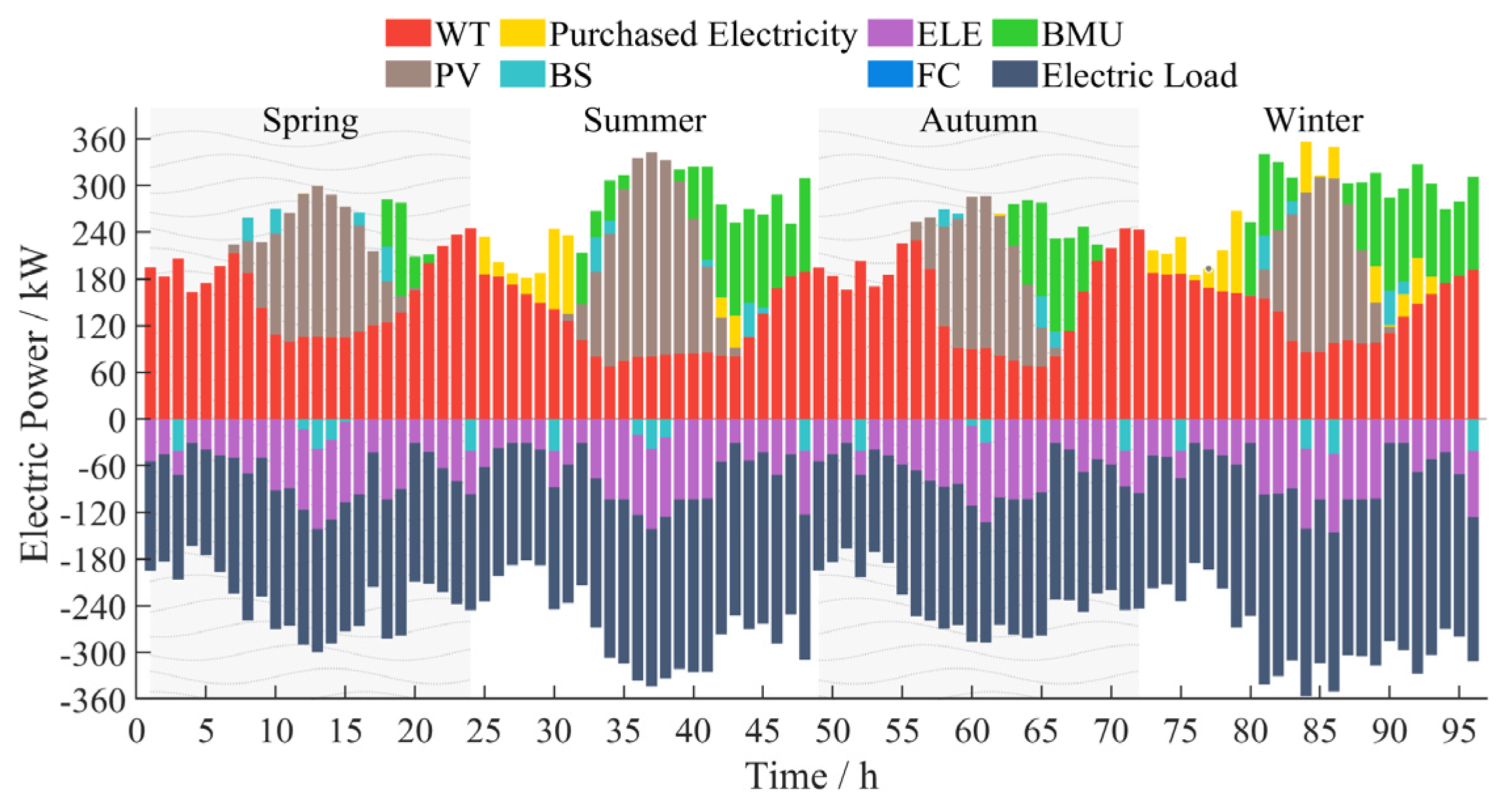

5.3. Comparative Analysis of the Economic Efficiency of On-Grid and Off-Grid Operation

5.4. Comparative Analysis of AWE and PEM at Different Time Points

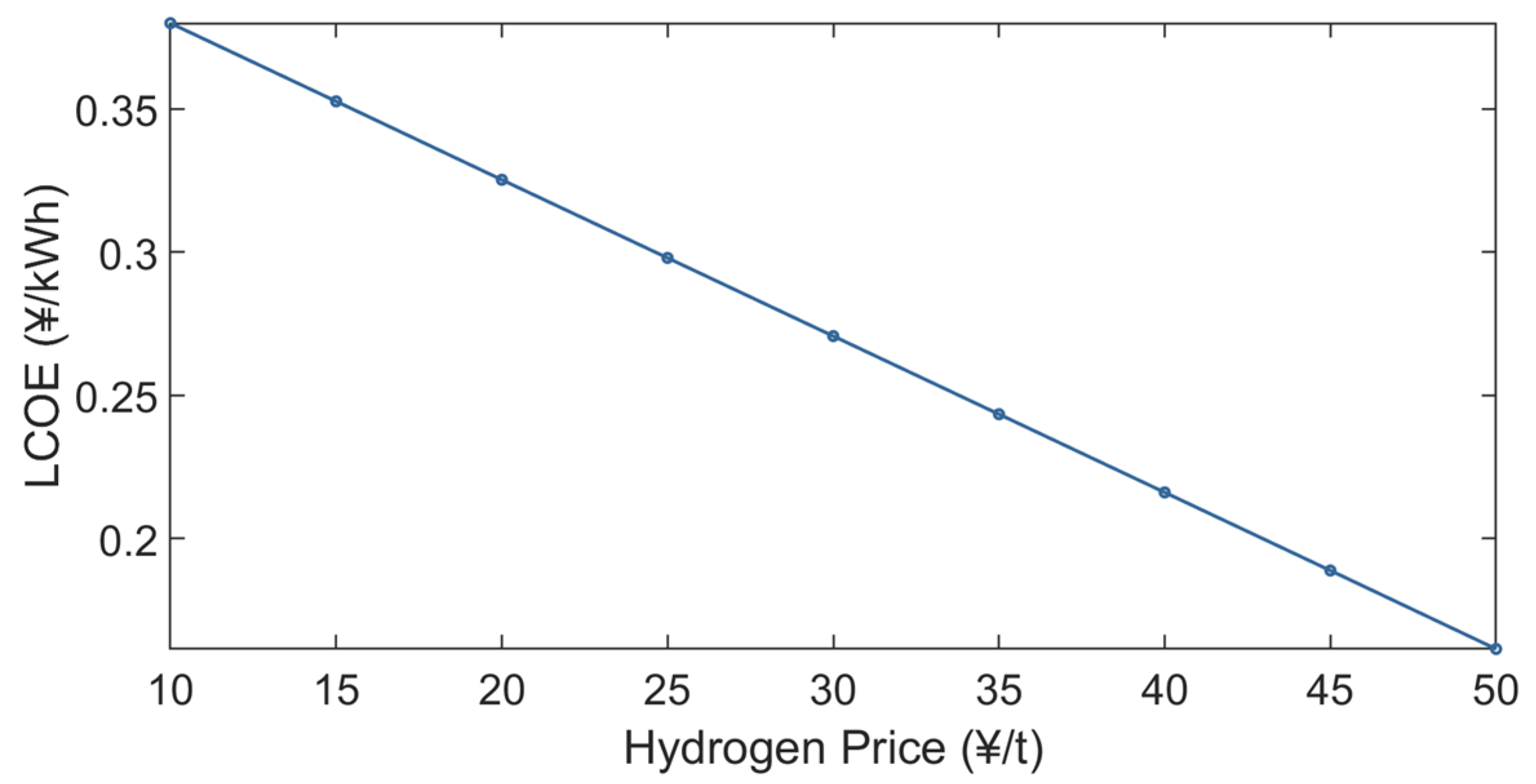

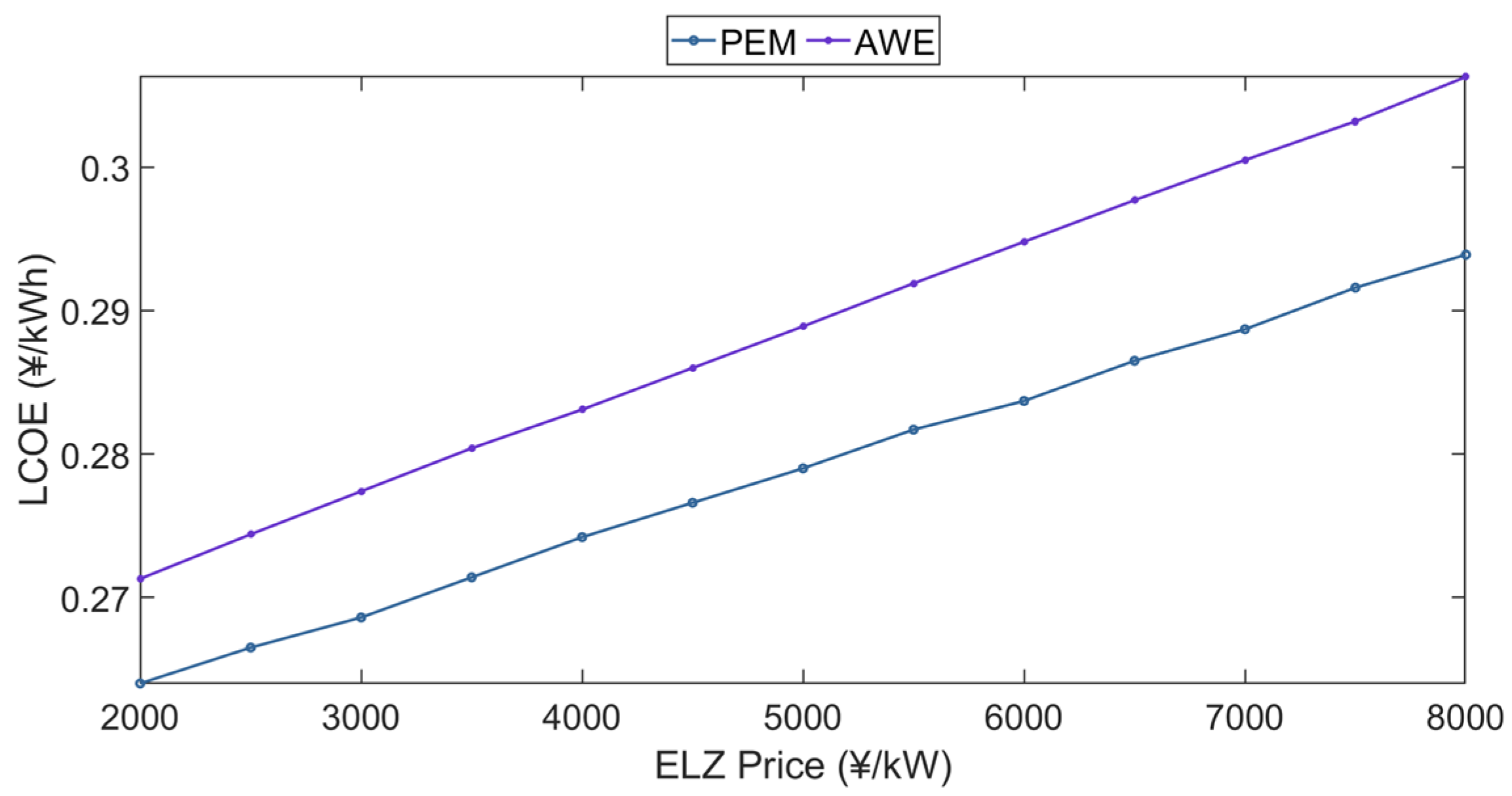

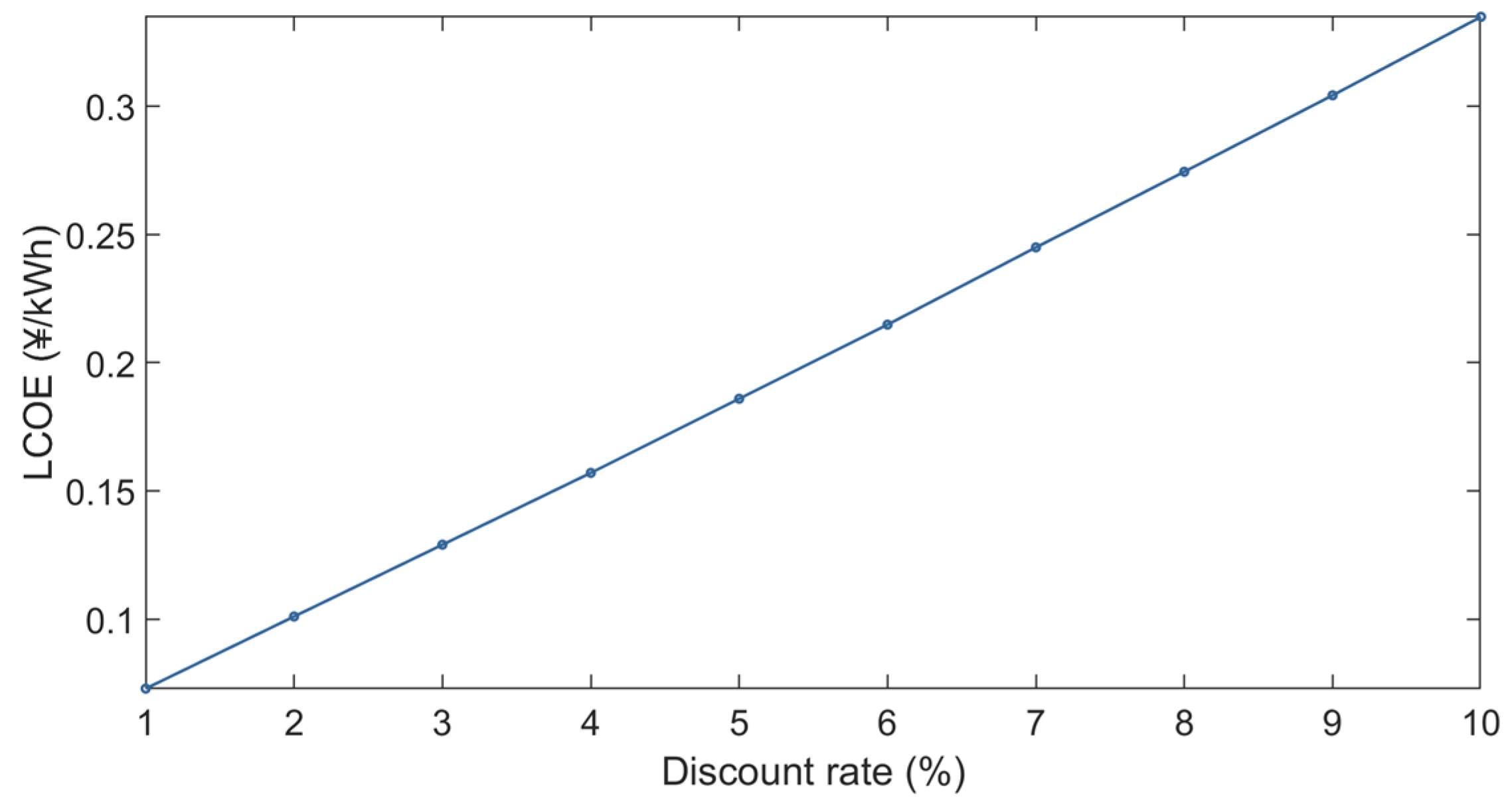

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

5.5.1. Hydrogen Price Analysis

5.5.2. Electrolyzer Price Analysis

5.5.3. Discount Rate Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussions

- (1)

- In the off-grid operation mode, the economic performance of selecting electric-hydrogen hybrid energy storage as the energy storage method is the best. The technical economic performance of configuring fuel cells for power generation is too poor and is not considered in the rural microgrid scenario.

- (2)

- Compared with the off-grid mode, the grid-connected mode can effectively reduce the equipment construction capacity, save floor space, and have better technical economic performance. It can effectively reduce the wind and solar power curtailment rate. Rural microgrids should try to choose the grid-connected mode.

- (3)

- The current PEM cost is too high, and AWE is the preferred hydrogen production method. However, after the cost of PEM is significantly reduced in the future, PEM will become the preferred hydrogen production method for rural microgrids due to its high hydrogen production efficiency and low minimum load limit.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Index of time periods: | |

| Index of year periods, | |

| The initial investment cost of the project | |

| The depreciation cost | |

| The total operation and maintenance cost of the rural microgrid project in year y | |

| The equipment operation and maintenance cost | |

| The electricity/biomass purchase costs | |

| The hydrogen product trading income | |

| The power of WT/PV/BMU/ELZ/FC/BS charge/BS discharge at time t | |

| The electricity purchase/load demand amount | |

| The hydrogen produced by the ELZ at time t | |

| The hydrogen consumed by the FC at time t | |

| The charge and discharge of hydrogen in the hydrogen storage tank at time t | |

| The hydrogen demand at time t | |

| The HS/BS energy status at time t | |

| The work state variables related to ELZ and FC at time t | |

| The work state variables related to the BS charge and discharge power | |

| The power generated per unit capacity of WT and PV | |

| The discount rate of the entire microgrid project | |

| The project life cycle | |

| The unit investment costs of WT/PV/BMU/BS/ELZ/HS/FC | |

| The construction capacity of WT/PV/BMU/BS/ELZ/HS/FC | |

| The depreciation rate of WT/PV/BMU/BS/ELZ/HS/FC | |

| The operation and maintenance rate of WT/PV/BMU/BS/ELZ/HS/FC | |

| The calorific value of hydrogen | |

| The hydrogen density | |

| The work efficiency of the ELZ/FC/BS | |

| The minimum load rate of the ELZ | |

| The upper limit of the BS charge and discharge power | |

| The proportional relationship between BS power and capacity | |

| The amount of electricity generated per unit of biomass consumed | |

| The upper and lower limit coefficients of HS capacity | |

| The upper and lower limit coefficients of BS capacity | |

| The curtailment rate of wind power/solar power respectively | |

| The self-balancing rate | |

| The amount of electricity provided to the load within the microgrid | |

| The total load demand | |

| The Euclidean distance of and | |

| / | The n-dimensional data points |

| / | The values of the i-th dimension of n-dimensional data points and |

| The cluster centers of the i-th cluster | |

| The number of clusters | |

| The i-th cluster |

Abbreviations

| AWE | alkaline water electrolyzer |

| PEM | proton exchange membrane |

| ELZ | electrolyzer |

| LCOE | the levelized cost of energy |

| FC | fuel cell |

| WT | wind turbine |

| PV | photovoltaics |

| BMU | biomass unit |

| BS | battery storage |

| HS | hydrogen storage |

| SSE | sum of squared errors |

Appendix A

References

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Planning renewable energy in rural areas: Impacts on occupation and land use. Energy 2018, 155, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Mahajan, D.; Varun, R.; Jain, V.; Sawle, Y. Optimal Planning and Design of an Off-Grid Solar, Wind, Biomass, Fuel Cell Hybrid Energy System Using HOMER Pro. In Recent Advances in Power Systems: Select Proceedings of EPREC-2021; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, 812; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Z. Optimal Sizing Design and Integrated Cost-Benefit Assessment of Stand-Alone Microgrid System with Different Energy Storage Employing Chameleon Swarm Algorithm: A Rural Case in Northeast China. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 1110–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, T.R.; Mosetlhe, T.C.; Yusuff, A.A.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.S.O. Off-grid hybrid renewable energy system with hydrogen storage for South African rural community health clinic. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19871–19885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Xu, Y.; Yi, Z.; Tu, Z. Energy Management for Rural Microgrid with Inaccurate Equipment Parameters: A KAN-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Guan, X.; Gao, K.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z. Key Technologies of Rural Integrated Energy System with Renewable Energy as the Main Body. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 979599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhai, Q.; Guan, X. Risk-Constrained Planning of Rural-Area Hydrogen-Based Microgrid Considering Multiscale and Multi-Energy Storage Systems. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckinley, P.C.; Wilber, M.; Whitney, E. Learning from Arctic Microgrids: Cost and Resiliency Projections for Renewable Energy Expansion with Hydrogen and Battery Storage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köprü, M.A.; Öztürk, D.; Yildirim, B. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Hybrid System for Rural Areas: Electricity and Heat Generation with Hydrogen and Battery Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 143, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, R.A.; Touti, E.; Aoudia, M.; Zahrouni, W.; Omar, A.I.; Elmetwaly, A.H. Innovative Hybrid Energy Storage Systems with Sustainable Integration of Green Hydrogen and Energy Management Solutions for Standalone PV Microgrids Based on Reduced Fractional Gradient Descent Algorithm. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Soto, J.D.L.; Azkona-Bedia, I.; Velazquez-Limon, N.; Romero-Castanon, T. A Techno-Economic Study for a Hydrogen Storage System in a Microgrid Located in Baja California, Mexico: Levelized Cost of Energy for Power to Gas to Power Scenarios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30050–30061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluraiah, N.C.; Vijayapriya, P. Optimization, design, and feasibility analysis of a grid-integrated hybrid AC/DC microgrid system for rural electrification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 67013–67029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, S.; Li, H. Inter-Zone Optimal Scheduling of Rural Wind–Biomass-Hydrogen Integrated Energy System. Energies 2023, 16, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaouda, A.; Sayouti, Y. Design and economic analysis of a stand-alone microgrid system using Dandelion Optimizer—A rural case in Southwest Morocco. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Mohammedia, Morocco, 18–19 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, P.; Sivasankar, G. Enhancement Of Renewable Energy Equiped Remote Village Power Supply Management Using Hydrogen. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Electrical Energy Systems (ICEES 2023), Chennai, India, 23–25 March 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Mohammadi, A.; Kumar, R.; Cirrincione, M. Optimal design of a PV-RHFC hybrid micro-grid for rural electrification in Soa Village, Fiji. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Energy Technologies for Future Grids (ETFG), Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 3–6 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoukh, A.; Redouane, A.; Oubouch, N.; Hasnaoui, A.E. Optimizing off-grid energy solutions: A hybrid approach leveraging solar, wind, and biomass for sustainable development. Global Energy Interconnect. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elminshawy, N.A.S.; Diab, S.; Yassen, Y.E.S.; Elbaksawi, O. An energy-economic analysis of a hybrid PV/wind/battery energy-driven hydrogen generation system in rural regions of Egypt. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Firoozabadi, B. Building integrated photovoltaic with hydrogen storage as a sustainable solution in Iranian rural healthcare centers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, M.; Tanürün, H.E.; Aydin, N.; Ayyildiz, E. Strategic site selection for biohydrogen production: Enhancing rural sustainability through agricultural biomass. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 89, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, I.; Bohre, A.K. Impact of green hydrogen power generation on HRES for rural area including EV and home loads. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Renewable Energy and Sustainable E-Mobility Conference (RESEM), Bhopal, India, 17–18 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backurs, A.; Jansons, L.; Laizans, A. Water Electrolysis Technologies: Comparison of Maturity, Operational and Cost Efficiency. In Proceedings of the 24th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrailov, D.Y.; Boycheva, S.V. Study assessment of water electrolysis systems for green production of pure hydrogen and natural gas blending. In Proceedings of the Innovations in Energy and Environment—InnoEE 2023, Sofia, Bulgaria, 17–19 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafie, M. Hydrogen production by water electrolysis technologies: A review. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. PEM water electrolysis for hydrogen production: Fundamentals, advances, and prospects. Carbon Neutrality 2022, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, A.; Spliethoff, H. Current status of water electrolysis for energy storage, grid balancing and sector coupling via power-to-gas and power-to-liquids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alssalehin, E.; Holborn, P.; Pilidis, P. Techno-Economic Environmental Risk Analysis (TERA) in Hydrogen Farms. Energies 2025, 18, 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghanem, M.; Almohamadi, H.; Haddad, S.; Mellit, A.; Chettibi, N. The effect of voltage and electrode types on hydrogen production powered by photovoltaic system using alkaline and PEM electrolyzers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munther, H.; Hassan, Q.; Khadom, A.A.; Mahood, H.B. Evaluating the techno-economic potential of large-scale green hydrogen production via solar, wind, and hybrid energy systems utilizing PEM and alkaline electrolyzers. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 5, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Min, I.; Lee, J.; Yang, H. An Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Electrolysis for Certifying Clean Hydrogen. Energies 2024, 17, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lin, J.; Zhang, M.; Sha, L.; Yang, B.; Liu, F.; Song, Y. Power controller design for electrolysis systems with DC/DC interface supporting fast dynamic operation: A model-based and experimental study. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuerowo, T.; Bade, S.O.; Akinmoladun, A.; Oni, B.A. The integration of wind and solar power to water electrolyzer for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 76, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, S.R.; Arsad, A.Z.; Ker, P.J.; Hannan, M.A.; Tang, S.G.H.; Goh, S.M.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Recent advancement in water electrolysis for hydrogen production: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis and technology updates. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 60, 780–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, Y.; Wei, W. Robust coordination control strategy for large-scale alkaline water electrolyzers driven by renewable energy. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 9957–9971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Koning, V.; de Groot, M.T.; de Groot, A.; Mendoza, P.G.; Junginger, M.; Kramer, G.J. Present and future cost of alkaline and PEM electrolyser stacks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32313–32330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasadnia, M.; Mehrpooya, M. Large-scale liquid hydrogen production methods and approaches: A review. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Pan, Q.; Xu, J.; Fang, T. Current situation and prospect of hydrogen storage technology with new organic liquid. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 17442–17451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Z. Research Progress and Application Prospects of Solid-State Hydrogen Storage Technology. Molecules 2024, 29, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Dong, X.; Wang, H.; Gong, M. Economic analysis of compressed gaseous hydrogen, liquid hydrogen, and cryo-compressed hydrogen storage methods for large-scale storage and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 162, 150725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, Z. A Comprehensive Overview of Hydrogen-Fueled Internal Combustion Engines: Achievements and Future Challenges. Energies 2021, 14, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xue, J.; Gao, H.; Ma, N. Hydrogen-fueled gas turbines in future energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhilef, S.; Saidur, R.; Safari, A. Comparative study of different fuel cell technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerinejad, H.; Eicker, U.; Ahmadi, P. Renewable fuel-powered micro-gas turbine and hydrogen fuel cell systems: Exploring scenarios of technology, control, and operation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 319, 118944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Z.S.; Khodaei, A.; Bahramirad, S.; Zhang, L.; Paaso, A.; Lelic, M.; Flinn, D. Levelized Cost of Energy Calculations for Microgrid-Integrated Solar-Storage Technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition (T&D), Chicago, IL, USA, 12–15 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.D.; Smith, A.D. Incorporating performance-based global sensitivity and uncertainty analysis into LCOE calculations for emerging renewable energy technologies. Appl. Energy 2018, 216, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.M.; Nguyen, D.L.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Pham, T.N.; Phan, Q.T.; Tran, M.H. A Bi-level optimization for the planning of microgrid with the integration of hydrogen energy storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 63, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.S.; Ueda, S.; Furukakoi, M.; Zakir, M.N.; Ludin, G.A.; Elkholy, M.H.; Yona, A.; Elias, S.; Senjyu, T. Novel integration and optimization of reliable photovoltaic and biomass integrated system for rural electrification. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 4924–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftabzadeh, S.M.; Colombo, C.G.; Longo, M.; Foiadelli, F. K-Means and Alternative Clustering Methods in Modern Power Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 119596–119633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsun, R.C.; Rex, M.; Antoni, L.; Stolten, D. Deployment of Fuel Cell Vehicles and Hydrogen Refueling Station Infrastructure: A Global Overview and Perspectives. Energies 2022, 15, 4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Performance Parameter | AWE | PEM |

|---|---|---|

| Current density (A/cm2) | 0.25–0.45 | 1.0–2.0 |

| Single Electrolyzer Voltage (V) | 1.8–2.5 | 1.8–2.2 |

| Operating Pressure (bar) | 10–30 | 20–50 |

| Minimum Load Rate (%) | 20–40 | 0–10 |

| Efficiency (%) | 51–60 | 46–60 |

| Operating Temperature (°C) | 60–90 | 50–80 |

| Service Life (kh) | 55–120 | 60–100 |

| Maximum Rated Power per Unit (MW) | 6 | 3 |

| Hydrogen Yield per Unit (Nm3/h) | 1400 | 500 |

| Investment Cost (CNY/kW) | 4200–12,215 | 8400–14,000 |

| Equipment | Initial Investment Cost | Residual Value/% | Operation and Maintenance Rate/% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 6000 CNY/kW | 5 | 1.5 | |

| PV | 3750 CNY/kW | 5 | 1.5 | |

| BMU | 8000 CNY/kW | 5 | 1.5 | |

| BS | 1500 CNY/kWh | 10 | 1.1 | |

| AWE | Year 2025 | 2500 CNY/kW | 5 | 3 |

| Year 2030 | 2260 CNY/kW | |||

| PEM | Year 2025 | 7500 CNY/kW | 5 | 3 |

| Year 2030 | 3800 CNY/kW | |||

| HS | 6000 CNY/Nm3 | 5 | 3 | |

| FC | 4000 CNY/kW | 5 | 3 | |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWE hydrogen production efficiency | 0.675 | PEM hydrogen production efficiency | 0.85 |

| The minimum load rate of AWE | 0.3 | The minimum load rate of PEM | 0.05 |

| 0.6 | 0.86 | ||

| / | 0.1/0.9 | / | 0.1/0.9 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | ||

| 2 h | 0.218 CNY/kWh | ||

| 29.33 CNY/kg | 155.65 CNY/t |

| Target | LCOE/(CNY/kWh) | WT/kW | PV/kW | BMU/kW | ELZ/kW | HS/m3 | FC/kW | BS/kWh | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 0.4219 | 467 | 250 | 128 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 132 | 4.2% | 0 |

| Case 2 | 0.2851 | 702 | 376 | 120 | 104 | 290 | 0 | 0 | 7.55% | 2.87% |

| Case 3 | 0.2824 | 672 | 403 | 125 | 102 | 250 | 0 | 66 | 6.38% | 0.31% |

| Target | LCOE/(CNY/kWh) | WT/kW | PV/kW | BMU/kW | ELZ/kW | HS/m3 | BS/kWh | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off-grid | 0.2824 | 672 | 403 | 125 | 102 | 250 | 66 | 6.38% | 0.31% | 100% |

| On-grid | 0.2744 | 610 | 428 | 120 | 103 | 176 | 88 | 4.47% | 0.16% | 94.43% |

| Target | Year | LCOE/(CNY/kWh) | WT/kW | PV/kW | BMU/kW | ELZ/kW | HS/m3 | BS/kWh | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWE | 2025 | 0.2744 | 610 | 428 | 120 | 103 | 176 | 88 | 4.47% | 0.16% | 94.43% |

| 2030 | 0.2730 | 610 | 428 | 120 | 103 | 176 | 88 | 4.47% | 0.16% | 94.43% | |

| PEM | 2025 | 0.2916 | 610 | 428 | 120 | 79 | 94 | 157 | 7.24% | 1.62% | 95.48% |

| 2030 | 0.2726 | 610 | 428 | 120 | 85 | 88 | 171 | 7.25% | 0.92% | 95.43% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Cui, S.; Fang, J.; Ai, X.; Wang, S. Technical and Economic Analysis of Rural Hydrogen–Electricity Microgrids. Processes 2025, 13, 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123878

Zhang Y, Wu Y, Qiu J, Zhang H, Li H, Cui S, Fang J, Ai X, Wang S. Technical and Economic Analysis of Rural Hydrogen–Electricity Microgrids. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123878

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yihan, Yan Wu, Jiajia Qiu, Hongkai Zhang, Huixuan Li, Shichang Cui, Jiakun Fang, Xiaomeng Ai, and Shiqian Wang. 2025. "Technical and Economic Analysis of Rural Hydrogen–Electricity Microgrids" Processes 13, no. 12: 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123878

APA StyleZhang, Y., Wu, Y., Qiu, J., Zhang, H., Li, H., Cui, S., Fang, J., Ai, X., & Wang, S. (2025). Technical and Economic Analysis of Rural Hydrogen–Electricity Microgrids. Processes, 13(12), 3878. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123878