3.4.1. Extraction and Analysis of Time Series Data Features for Low-Production Wells

- (1)

Level feature extraction

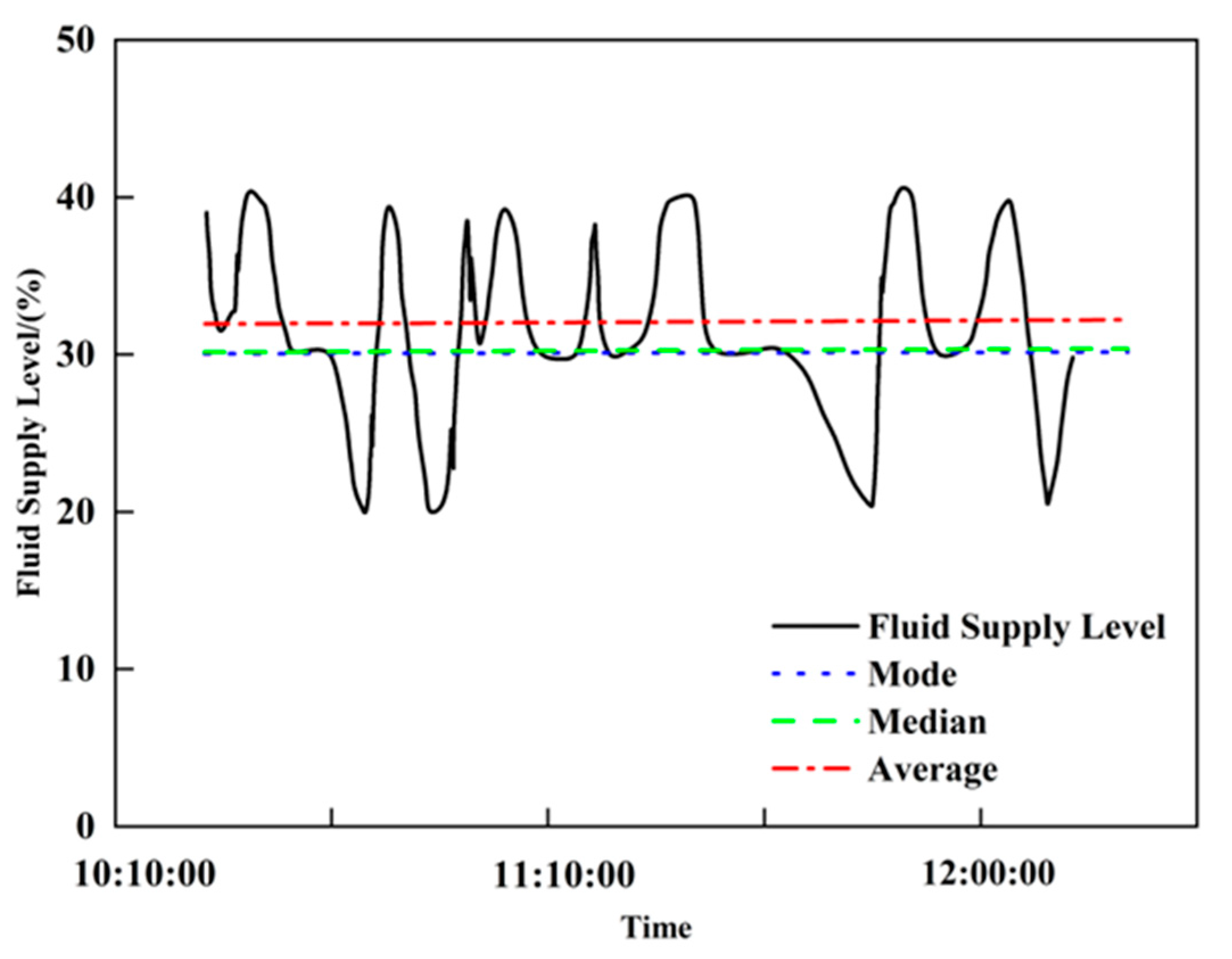

The level features of the low-production well time series data reflect the average state of the data over a period and are used to describe its overall stability level. The median, mode and mean are extracted as the level features of the liquid supply level. The median reflects the central value of the data but is less accurate when the distribution is uneven and its segment often coincides with the mode; by contrast, the mean varies with all data points and more comprehensively reflects the data level.

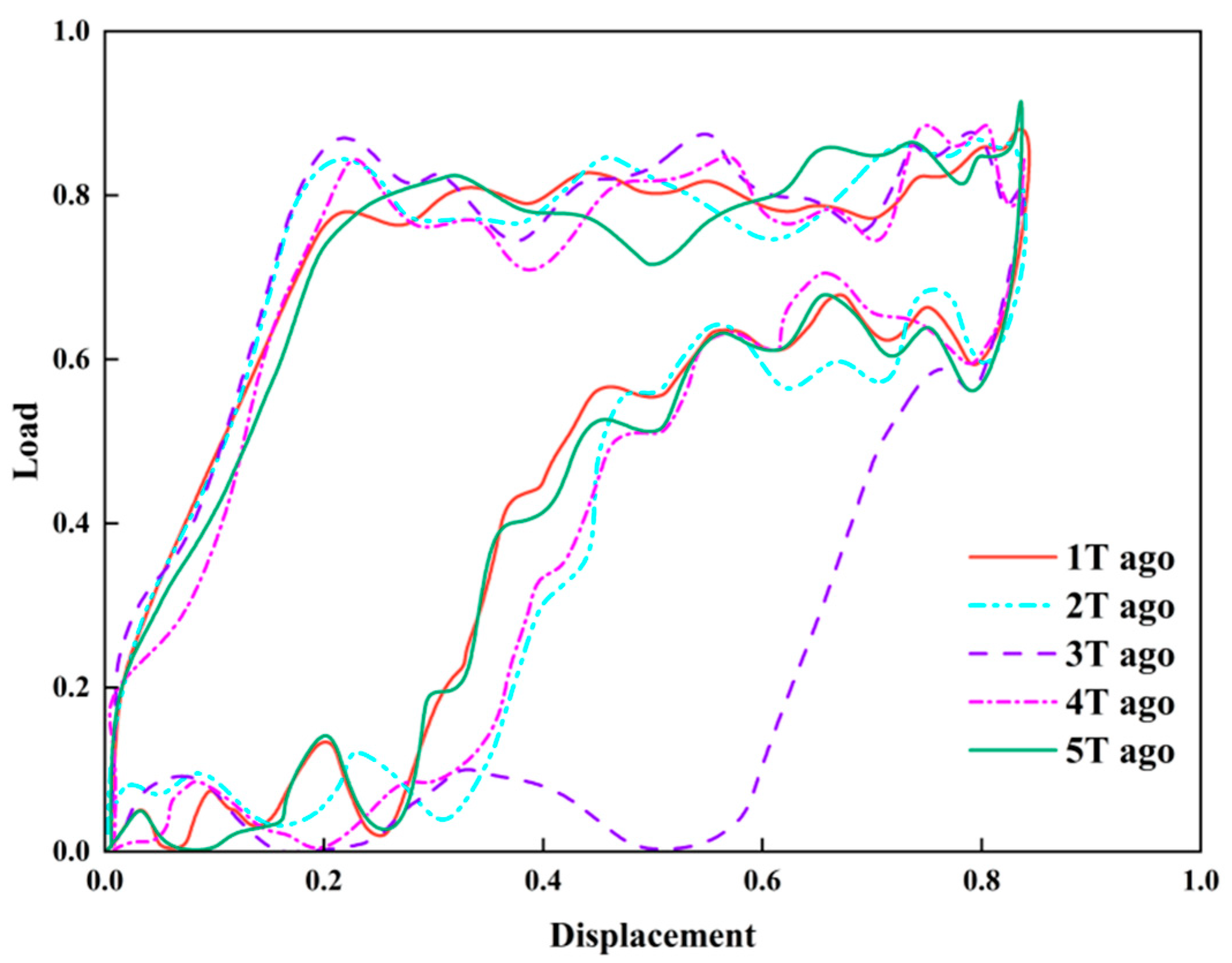

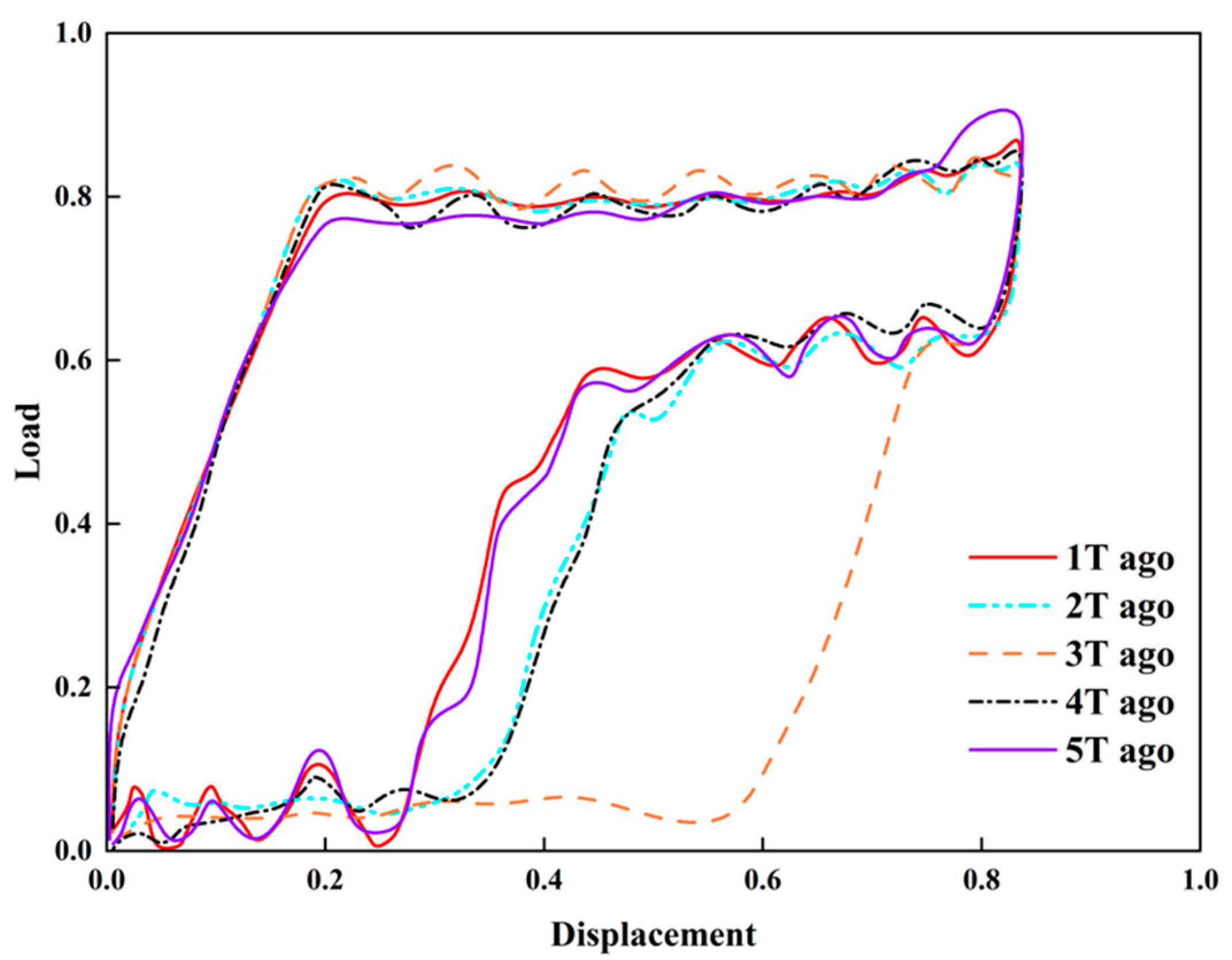

The results of the long-term level feature analysis for the liquid supply level are shown in

Figure 22. When extracting short-term and long-term level features for the low-production well time series data, the mean is used comprehensively. Taking the liquid supply level as an example: when the mean is above the normal level, it indicates higher formation energy; when equal to the normal level, it indicates normal formation energy; when below the normal level, it indicates relatively low formation energy.

- (2)

Trend feature extraction

The trend features of the low-production well time series data reflect the direction of change over a period and are an important basis for forecasting and planning in a time series analysis. Because the liquid supply level, dynamic fluid level, and production rate exhibit different trends at different time scales, short-term and long-term trend features must be extracted separately. The short-term trend can be characterized by the relative change rate, whose mathematical expression is as follows:

In the formula, is the relative change rate; is the final value; is the initial value.

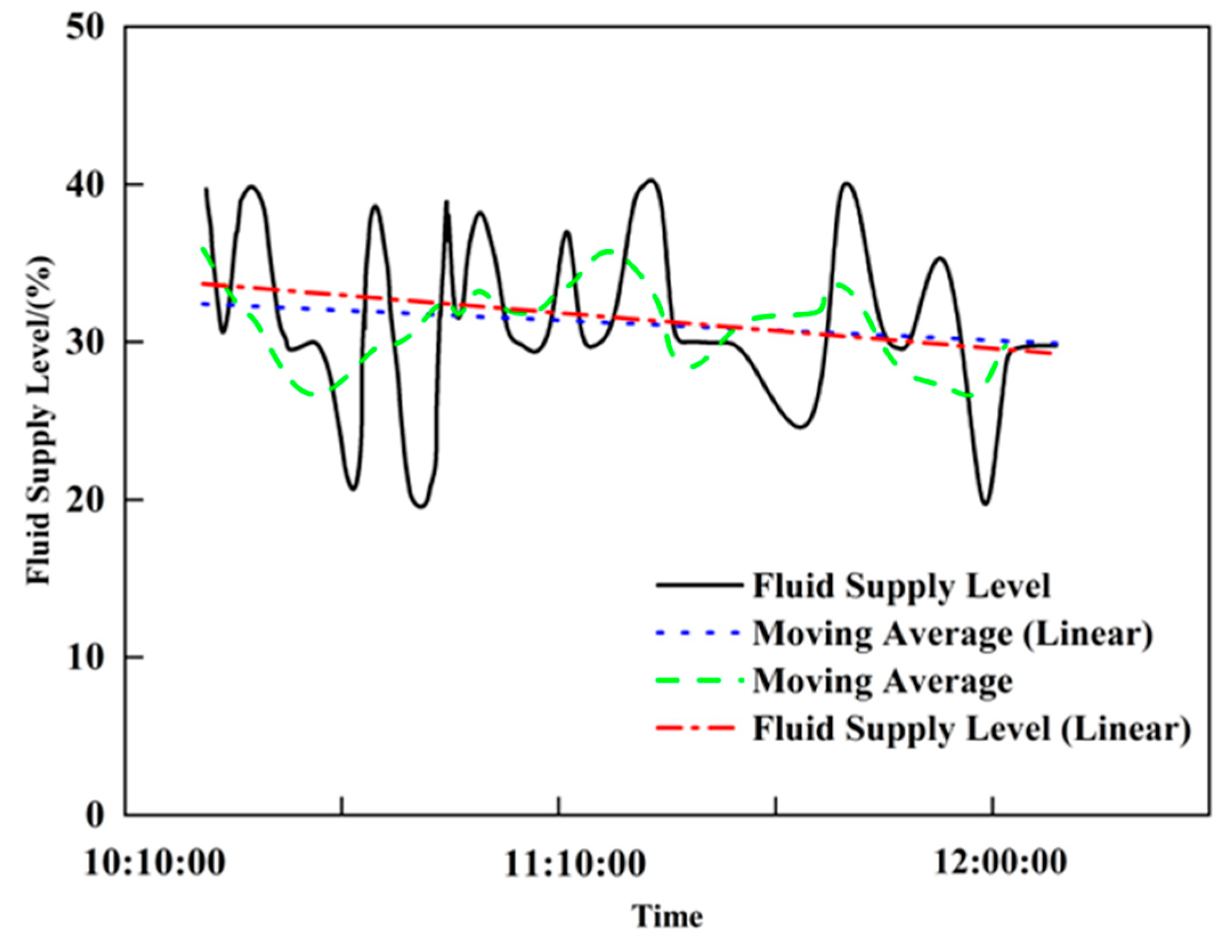

When the relative change rate is positive, the data show an upward trend, indicating high formation energy; when zero, the data remain unchanged, indicating normal energy; when negative, the data decline, indicating low formation energy. Because downhole conditions are complex, long-term time series data usually show irregular changes and it is necessary to compare different trend extraction methods; among them, the moving average method and the linear regression method are two commonly used methods. Using the liquid supply level data from Low-production Well-1 and Low-production Well-2 as examples, trend features were extracted, respectively, by the moving-average method (Formulas (37) and (38)) and the linear regression method (Formulas (39) and (40)).

In the formulas: is the liquid supply level; is time.

Table 8 summarizes the moving average method and the linear regression method for trend feature extraction and provides a comparative illustration of their core characteristics.

As shown in

Figure 23 and

Figure 24, the black solid line represents the Fluid Supply Level, the blue dashed line denotes the Moving Average (Linear), the green dash-dotted line indicates the Moving Average, and the red dash-dotted line stands for the Fluid Supply Level (Linear). The vertical axis represents the Fluid Supply Level (%), and the horizontal axis indicates Time, presenting the changes in the fluid supply level and the results of different trend extraction methods from 10:10:00 to 12:00:00. The moving average and linear regression methods for Low-production Well-1 (

Figure 23) are negative, accurately reflecting the declining trend in the liquid supply level and indicating low formation energy; for Low-production Well-2 (

Figure 24), the decline in the liquid supply level is larger, and the linear regression slope (−3.4997) is significantly greater in magnitude than the moving average slope (−0.1005), indicating that linear regression is more precise for trend feature extraction.

In summary, by comparing the moving average and linear regression methods and considering the long-term characteristics of the low-production well time series data, linear regression is preferred to extract the three features. Data change is reflected by the curve slope: a positive slope indicates high formation energy, zero slope indicates normal formation energy, and a negative slope indicates low formation energy.

- (3)

Fluctuation feature extraction

The fluctuation features of the low-production well time series data reflect the amplitude and frequency of changes, revealing the instability and volatility of the data.

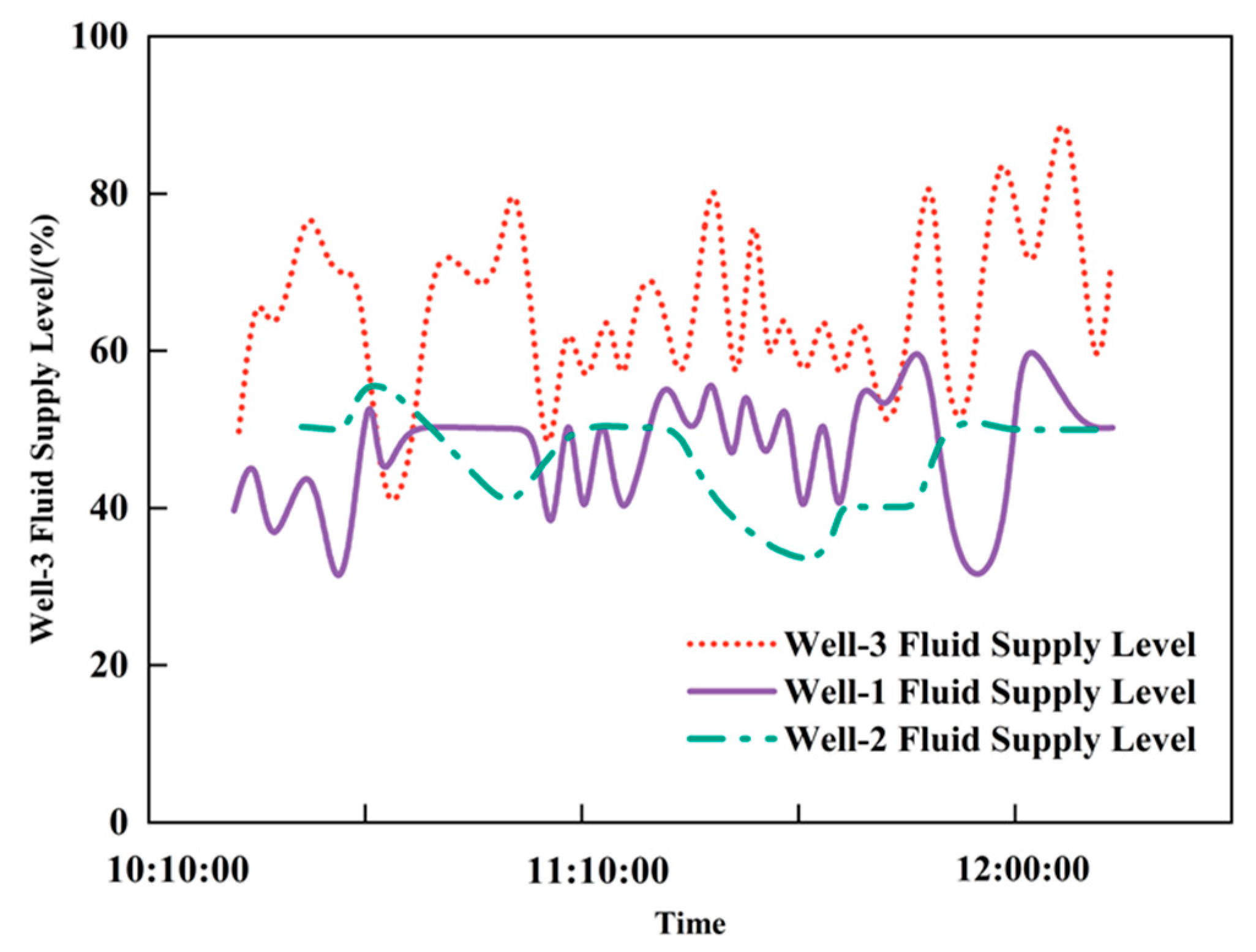

Table 9 lists three extraction methods: standard deviation, variance and range. Taking the liquid supply level time series data from Low-production Wells-1, -2 and -3 as examples, the fluctuation features for the three wells are shown in

Figure 25.

Figure 25 illustrates the fluid supply level trends of three wells over time: the red dotted line represents Well-3, the purple solid line denotes Well-1, and the green dash-dotted line indicates Well-2. The vertical axis stands for Fluid Supply Level (%), and the horizontal axis represents Time, presenting the dynamic fluid supply changes and capacity patterns of the three wells from 10:10:00 to 12:00:00, with the corresponding data shown in

Table 9, the standard deviation, variance and range were calculated for the liquid supply level of Wells-1, -2 and -3. If the range is used, Well-3 shows the largest fluctuation while Wells-1 and -2 show the same fluctuation, which contradicts

Figure 25, because the range only reflects the maximum and minimum values and ignores intermediate changes. Therefore, both standard deviation and variance can accurately reflect fluctuation, with the standard deviation being more intuitive and suitable as the fluctuation feature for liquid supply level.

Because the short-term window is brief, fluctuation features do not need to be extracted for the short term; only long-term fluctuation features are extracted for the low-production well time series data. When the standard deviation is above the normal fluctuation range, formation energy is relatively high; when within the normal range, formation energy is normal; when below the normal range, formation energy is relatively low.

- (4)

Example of feature extraction

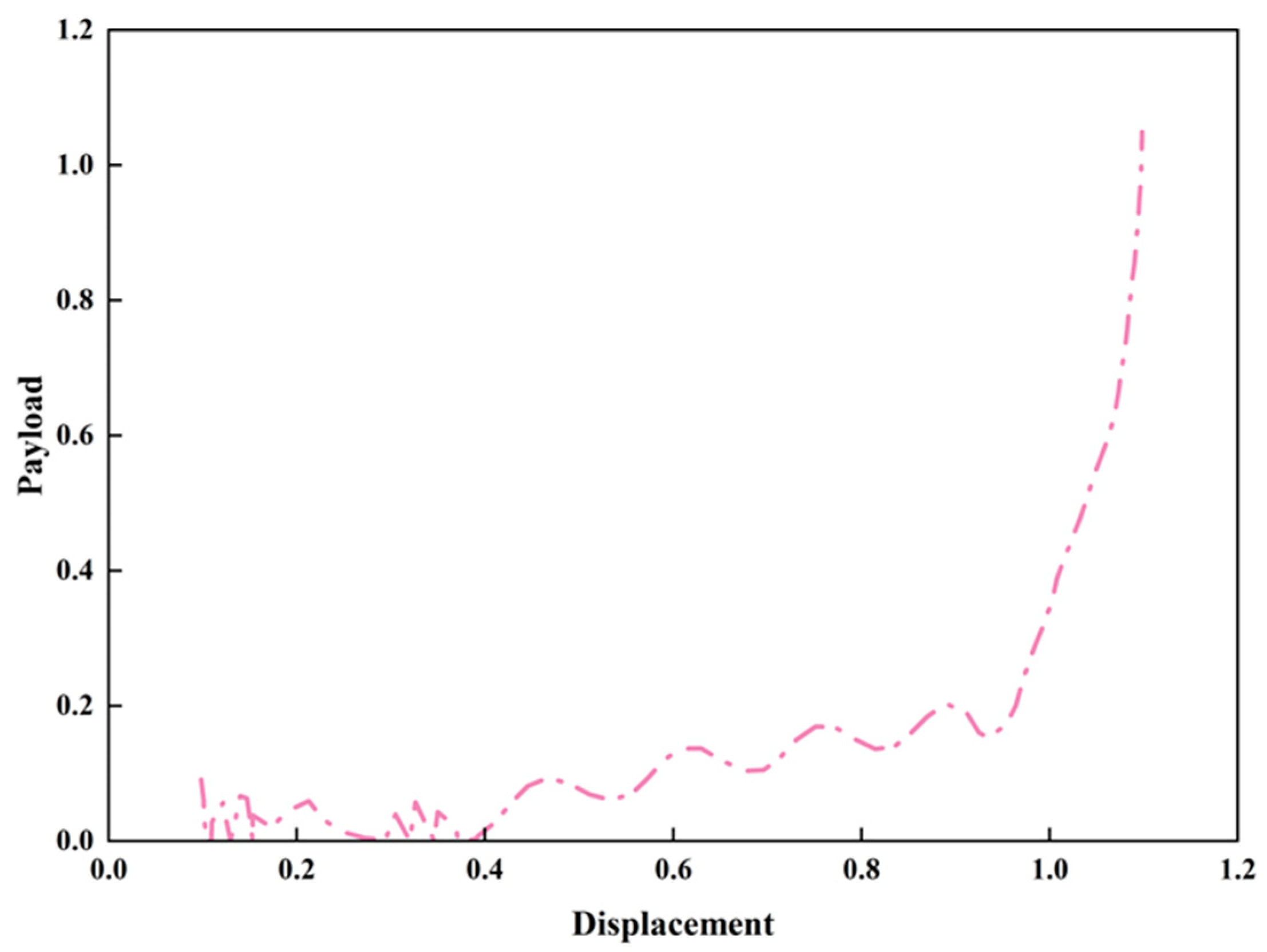

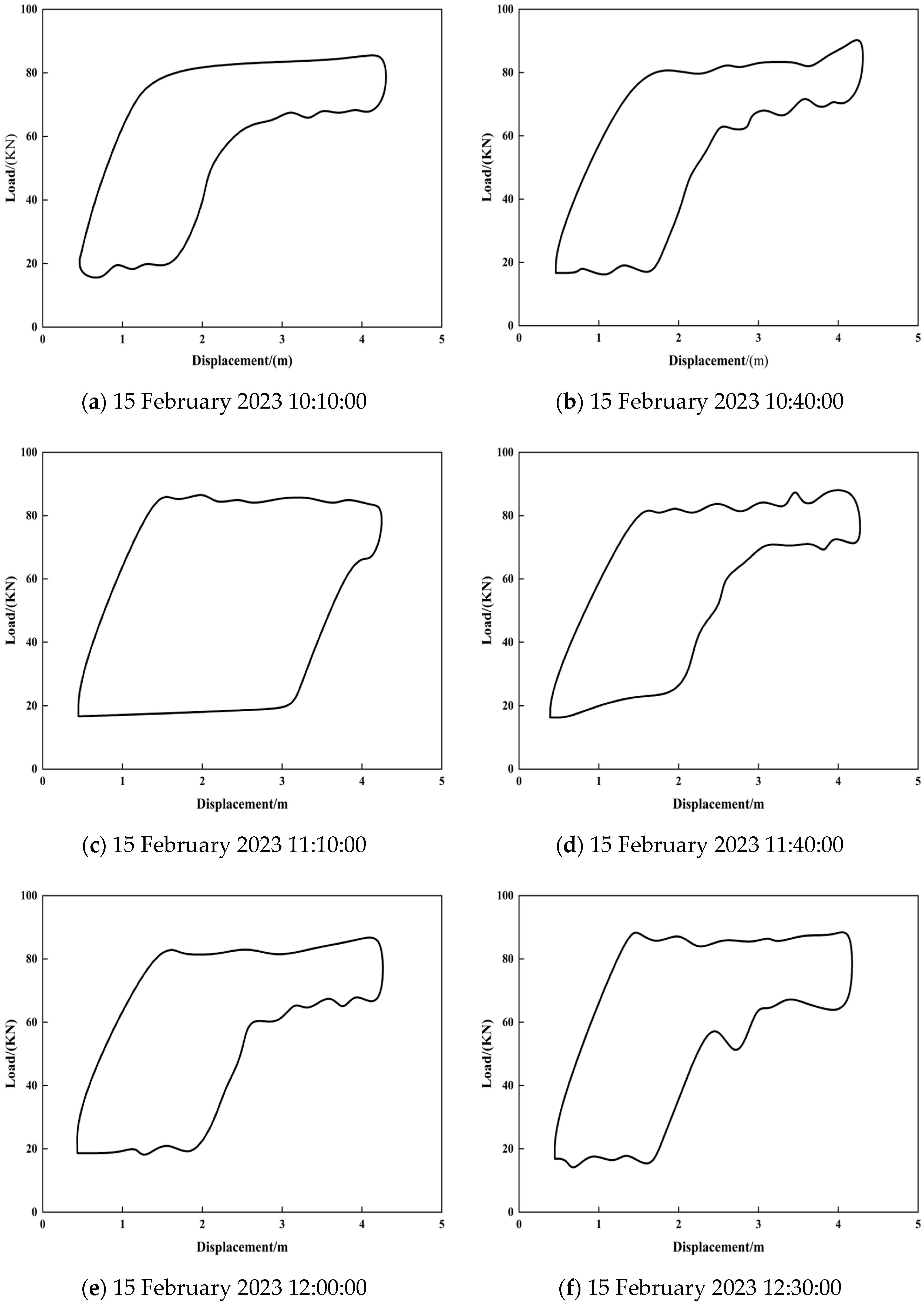

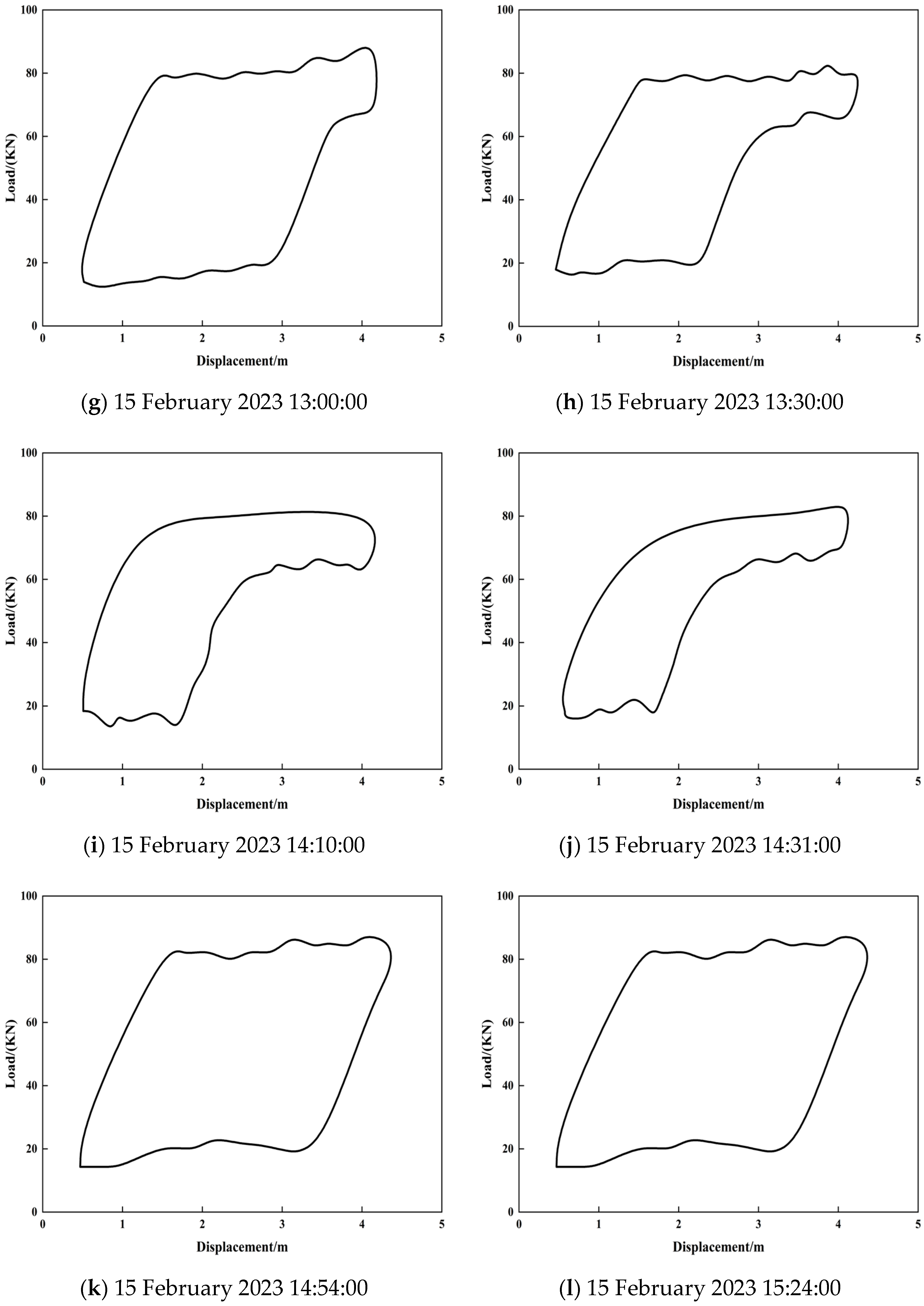

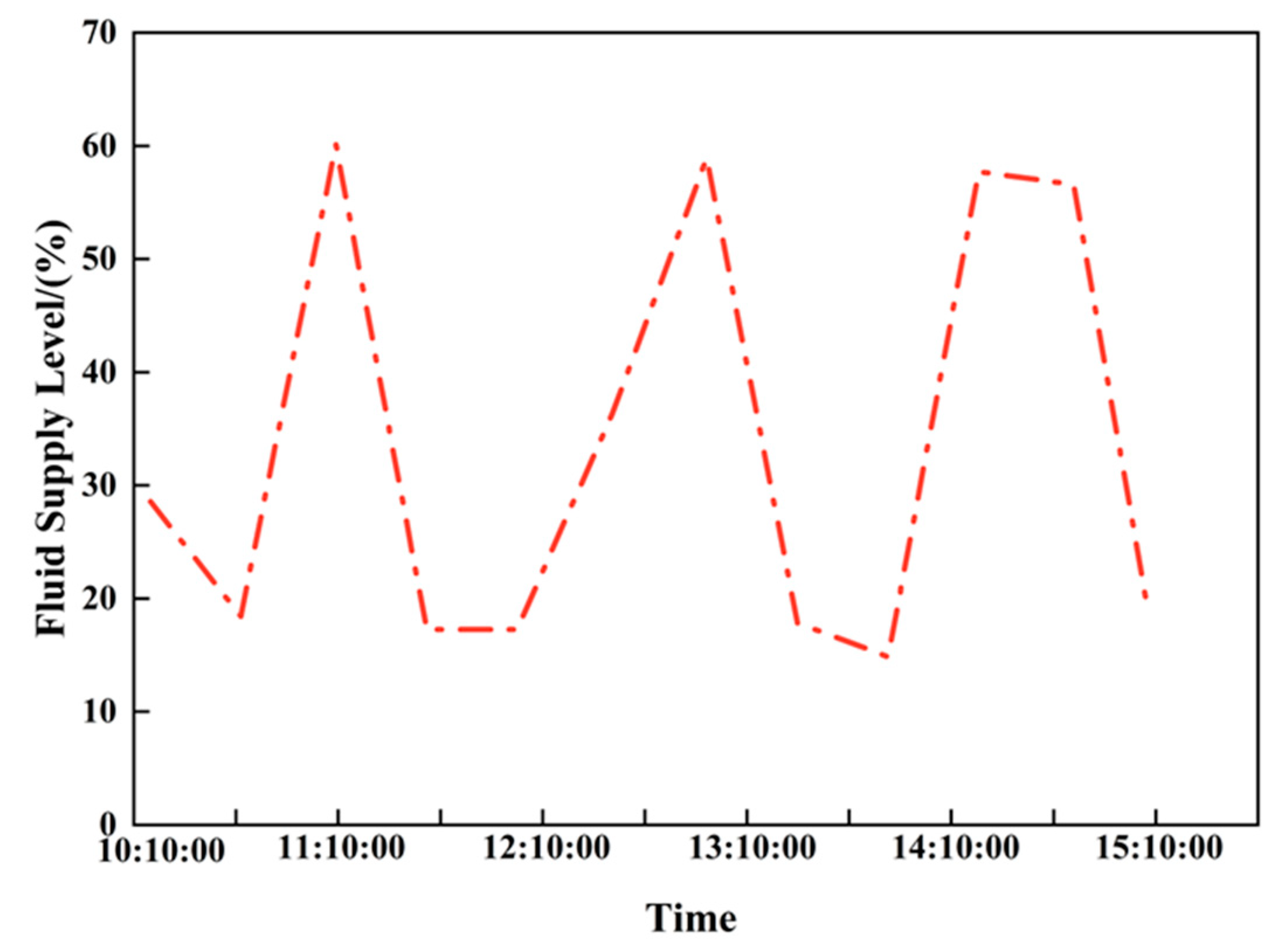

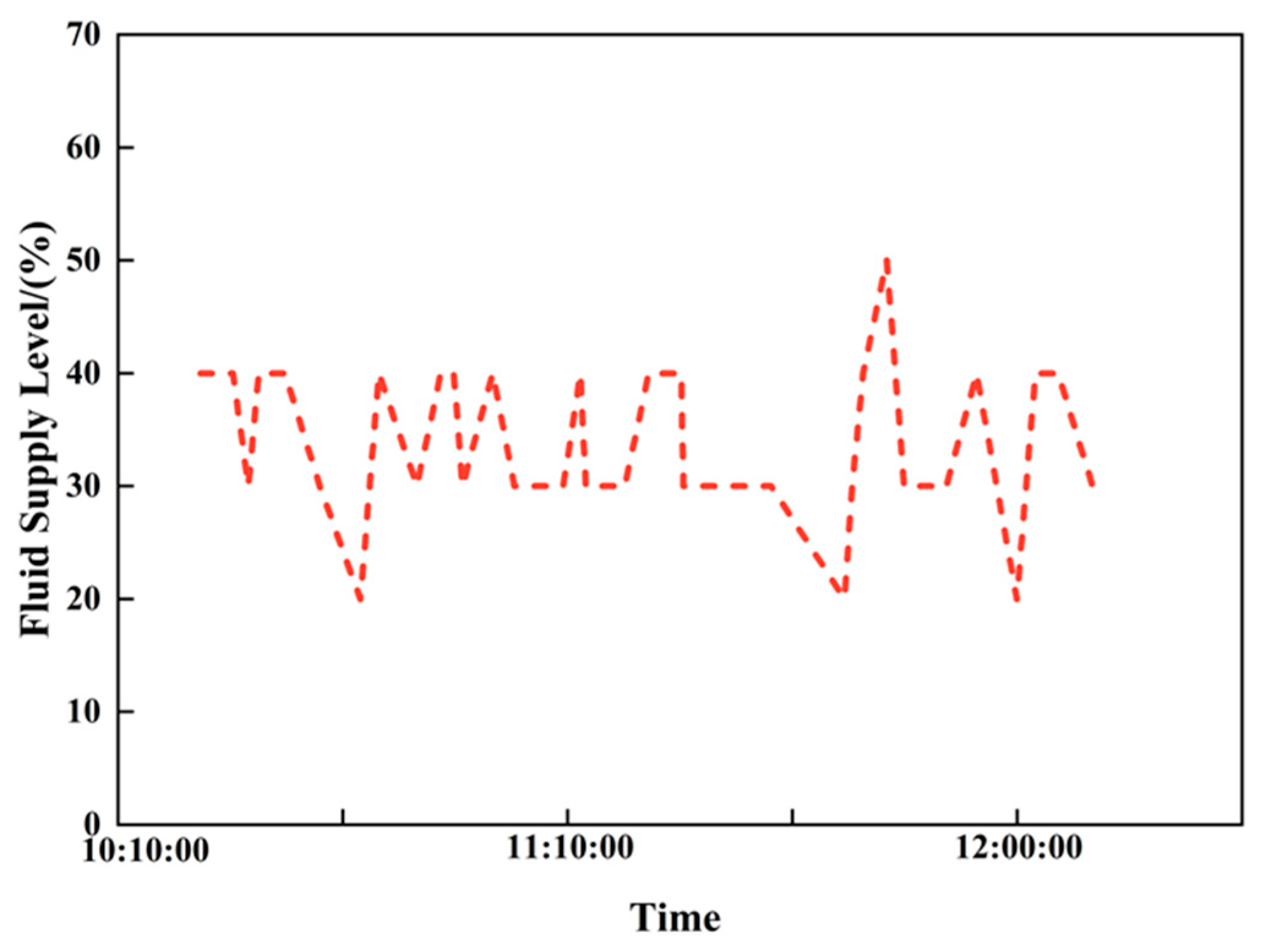

Time series data of the liquid supply level from an actual field are selected as the study index; the liquid supply level time series for the low-production well is shown in

Figure 26. The normal level for this well is 61%, the normal trend is 0.018, and the normal fluctuation range is [6.68, 10.08].

As shown in

Table 10, in the short-term time window, the well’s level is 46.11% with a trend change of −1.33; in the long-term window, the level is 43.55% with a trend change of −3.20 and a fluctuation of 8.77. The comprehensive feature analysis indicates that the well’s formation energy is relatively low and production parameter optimization is required.

3.4.2. Production Parameter Optimization for Low-Production Wells Based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

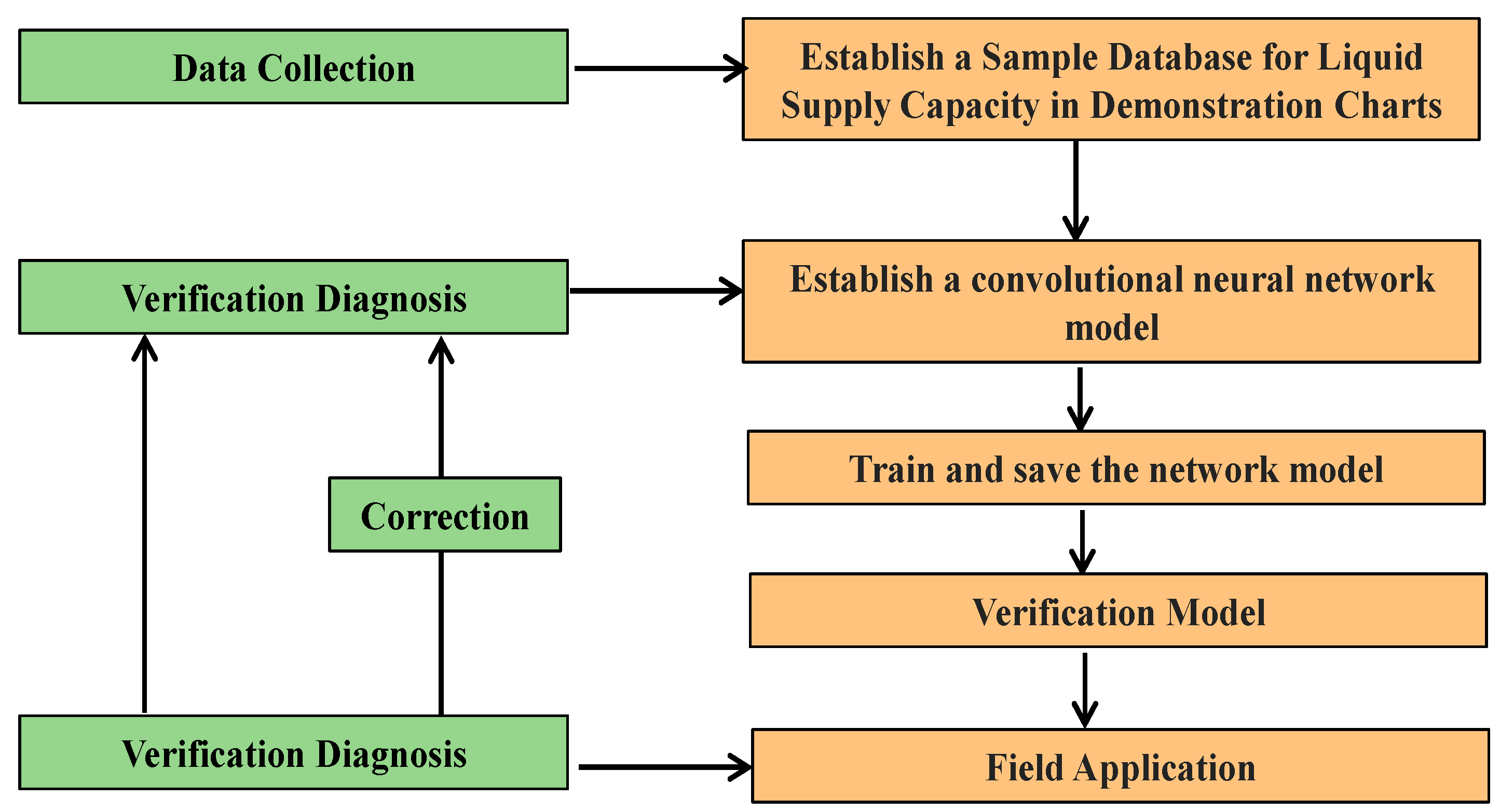

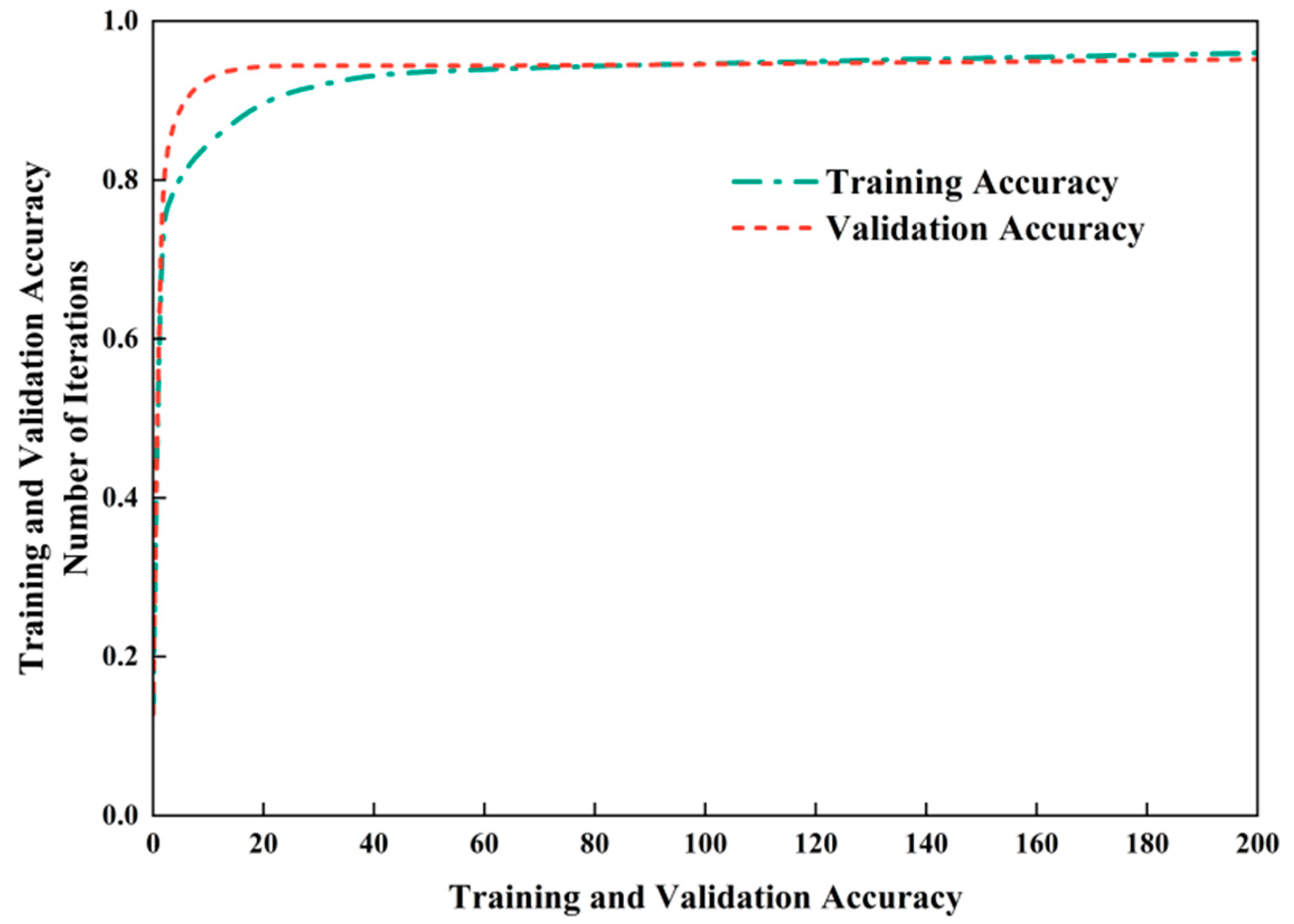

Most existing production parameter optimization methods for low-production oil wells rely on single-factor decision-making based on the fluid supply degree derived from dynamometer cards, making it difficult to comprehensively characterize the integrated dynamic changes in formation energy. To address this limitation, this study proposes a production parameter optimization method for low-production oil wells based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

This method constructs a weighted average comprehensive evaluation function to systematically integrate multi-dimensional indicators characterizing formation energy, including long-term and short-term fluid supply degrees, liquid production rate, and dynamic liquid level. It thereby realizes multi-index collaborative decision-making for production parameters and ultimately determines the optimal production parameter scheme based on the comprehensive decision results.

The optimization objective function is constructed with the core goal of “production improvement + energy consumption reduction”. Considering the production characteristics of low-production oil wells, such as limited fluid supply capacity and a relatively high proportion of energy consumption, this optimization abandons the single production-oriented decision-making logic and establishes a “production energy consumption” dual-objective optimization system. This system ensures an effective improvement in production capacity while achieving a significant reduction in energy consumption, with the mathematical expressions as follows:

Among them, q represents the displacement of the oil pump, s denotes the stroke length, and n is the pumping frequency. The core optimization logic is “maximizing daily oil production while minimizing the energy consumption per unit oil production under the premise of stable fluid supply”—which not only avoids problems such as equipment idle pumping and a sharp increase in energy consumption caused by blind production increase, but also solves the industry pain point of “high production without high efficiency” in low-production oil wells.

- (1)

Comprehensive decision-making for long-term feature changes

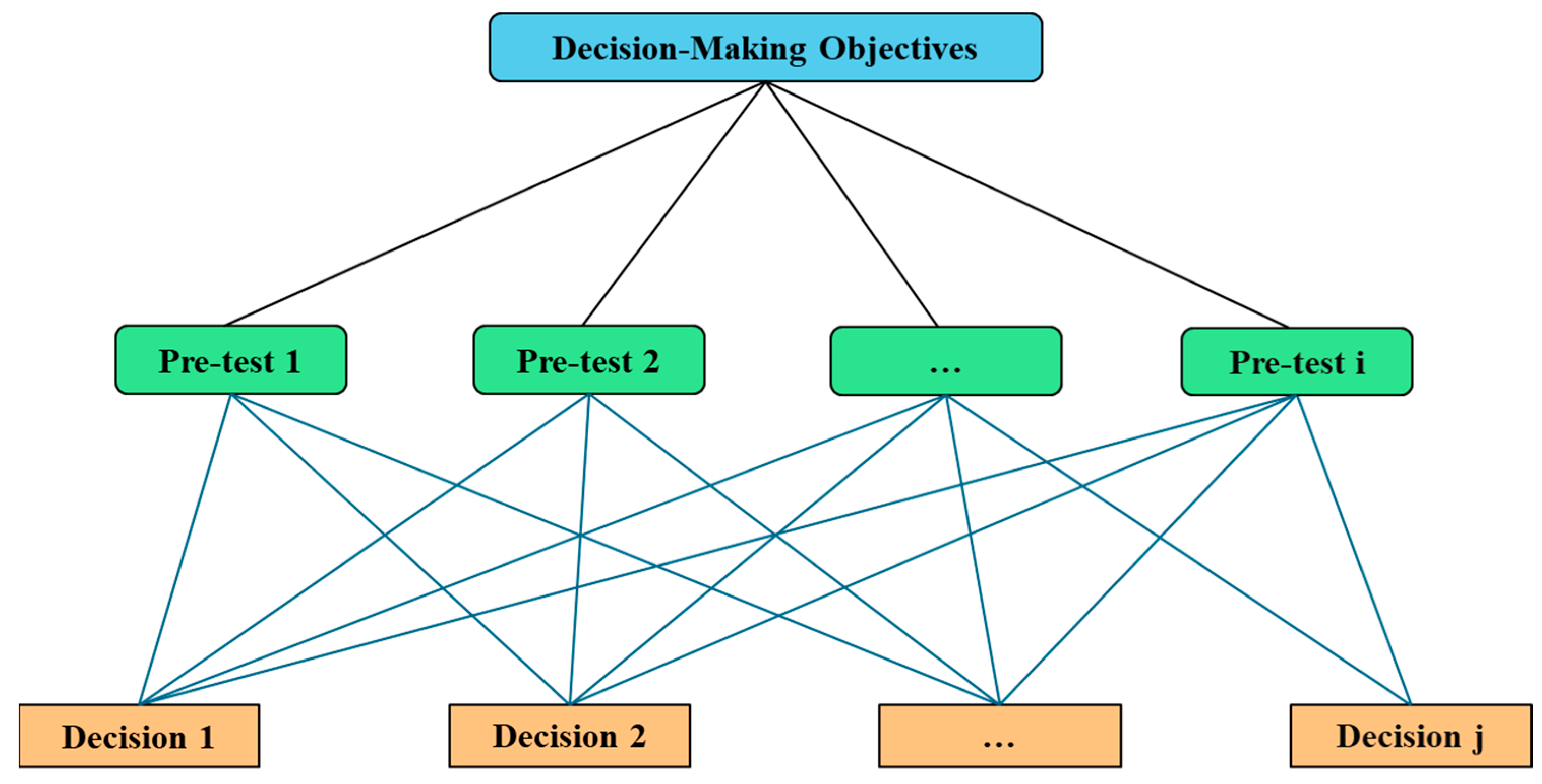

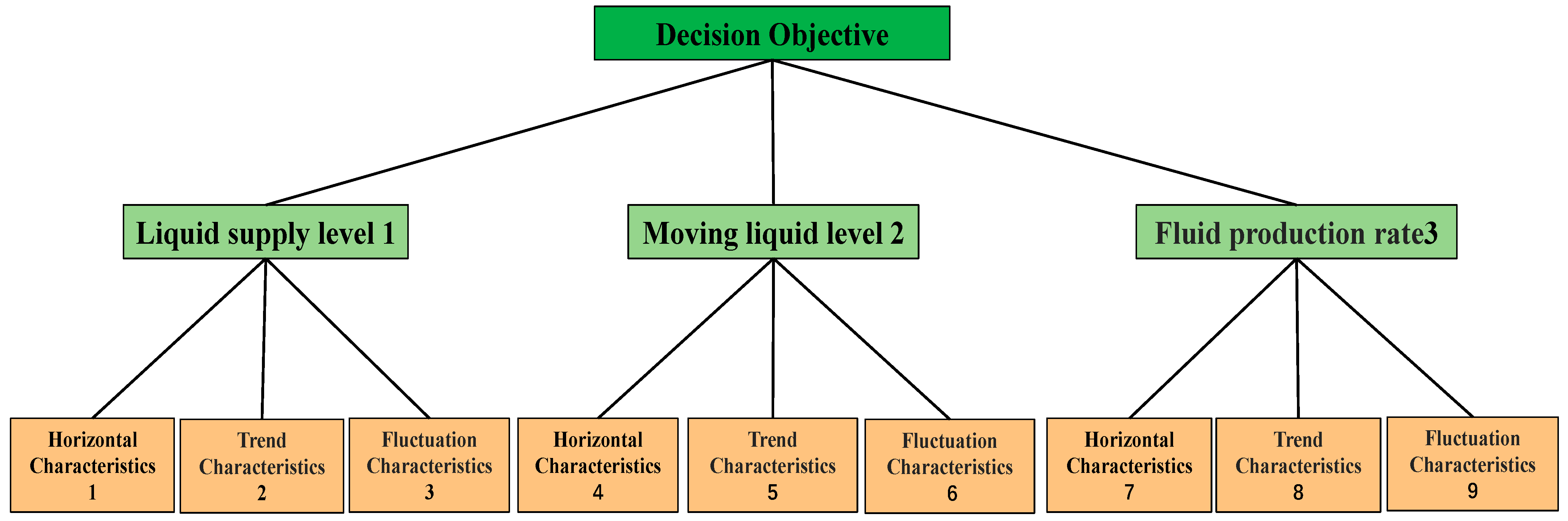

To optimize production parameters for low-production wells, level, trend and fluctuation features of liquid supply level, dynamic fluid level and production rate are first extracted from a long-term time window to provide the basis for optimization. Based on these features, a multi-level structural model for optimizing production parameters of low-production wells is established. The hierarchy for long-term production parameter optimization of low-production wells is shown in

Figure 27.

The judgment matrix is created by pairwise comparisons of each element, typically using Saaty’s 1–9 scale; the specific comparison scale values are shown in

Table 11.

Construct the judgment matrices and perform pairwise comparisons of the features using Saaty’s 1–9 scale (

Table 11) to determine relative importance and then compute the weights of each time series feature with respect to the decision objective (

Table 12 and

Table 13).

Next, single-level ranking and consistency checks are carried out, yielding the ranking weight vector , ; the consistency check produces: , , , and the judgment matrix passes the consistency test. Using the above steps, the weight vector:

. Then, an overall hierarchical ranking and consistency check are performed: based on the already determined weights of the criterion layer relative to the goal and the weights of the decision layer relative to the criterion layer, the overall hierarchical ranking

, is obtained, and the judgment matrices pass the consistency checks.

Finally, compute the comprehensive decision result from the overall hierarchical ranking and consistency checks using the criterion-to-goal and decision-to-criterion weights, thereby constructing the long-term feature comprehensive decision model. The corresponding results are detailed in the overall summary table in the subsequent section.

- (2)

Comprehensive decision-making for short-term feature changes

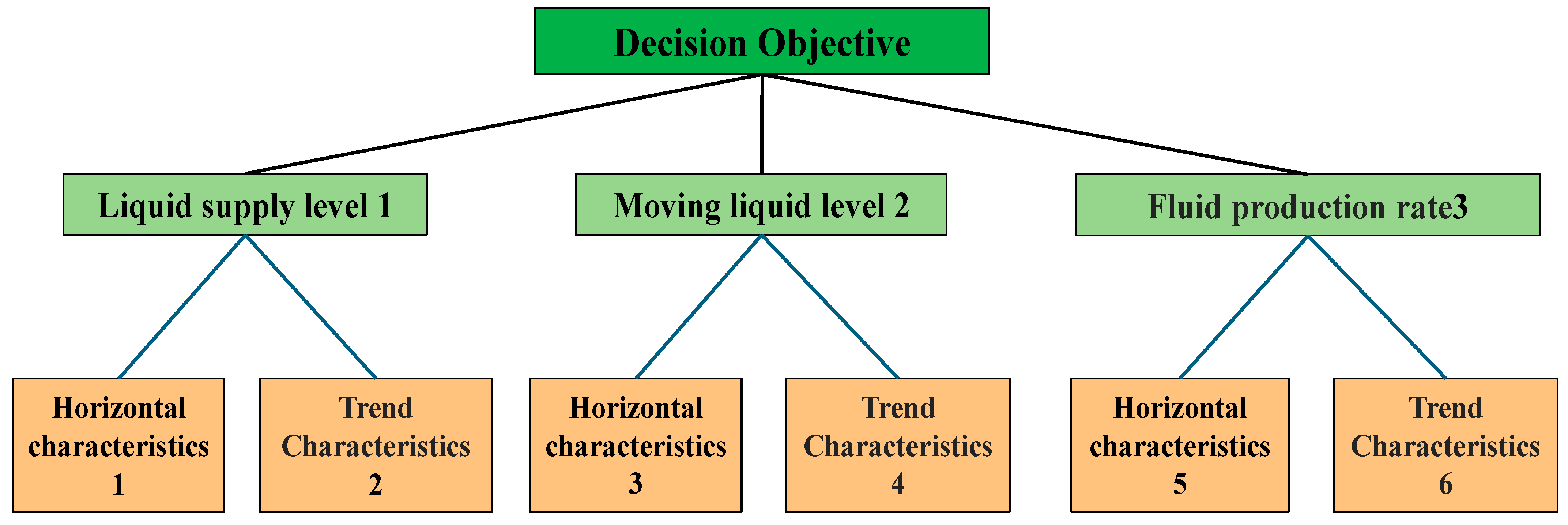

To optimize production parameters for a low-production well, level, trend and fluctuation features of the liquid supply level, dynamic fluid level and production rate are first extracted from a short-time window to provide the basis for optimization. Based on these features, a multi-level structural model for optimizing production parameters of low-production wells is established. The hierarchical structure for short-term optimization is shown in

Figure 28.

Construct judgment matrices and perform pairwise comparisons of the features using Saaty’s 1–9 scale (

Table 11) to determine relative importance, and from these, compute the weights of each time series feature with respect to the decision objective (

Table 14).

Next, single-level ranking and consistency checks are performed, yielding the ranking weight vector , . The consistency check gives , and the judgment matrix passes the consistency test.

Using the above steps the weight vector

is calculated. Then perform overall hierarchical ranking and consistency checks: based on the already determined weights of the criterion layer relative to the goal and the decision layer relative to the criterion layer, compute the overall weights:

. The consistency yields

, indicating the pairwise comparison matrix passes the consistency test. Finally, construct the short-term feature comprehensive decision model; the results are shown in

Table 15.

- (3)

Comprehensive decision-making for combined long- and short-term features

Long-term feature changes reflect the long-term rising or falling trend of low-production well time series data, while short-term feature changes reflect short-term sudden changes and instability; the two are related in the data. Therefore, in production parameter optimization for low-production wells, short-term comprehensive decisions are integrated with long-term trend comprehensive decisions to form a combined long- and short-term decision. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, is the combined decision factor for long- and short-term features; is the time weight coefficient ( = 0.5); is the long-term feature decision function; is the short-term feature decision function; is the level feature; is the trend feature; is the fluctuation feature.

The AHP-based overall feature comprehensive decision results are shown in

Table 15.

According to the earlier single-factor decision example analysis, single-factor decisions have limitations in consistency and scientific validity: some decision factors need adjustment while others do not. Therefore, to achieve a scientifically reasonable optimization of production parameters for low-production wells, a comprehensive decision method is necessary.

From the above calculations, the combined weight of long-term features was determined to be , with the long-term decision factor equal to −0.613.

Meanwhile, the short-term feature weight is . Using the formula for combined long- and short-term decision-making, the resulting comprehensive decision factor is .

The comprehensive decision result falls within the negative adjustment interval , clearly indicating that a negative regulation of the pumping frequency of the low-production oil well should be implemented in the current time period. The core of this decision-making logic lies in moderately reducing the pumping frequency to dynamically match the pumping parameters with the formation fluid supply capacity, thereby avoiding idle pumping losses caused by blind production increase and ultimately achieving the coordinated optimization of the oil well’s production efficiency and energy consumption economy.