1. Introduction

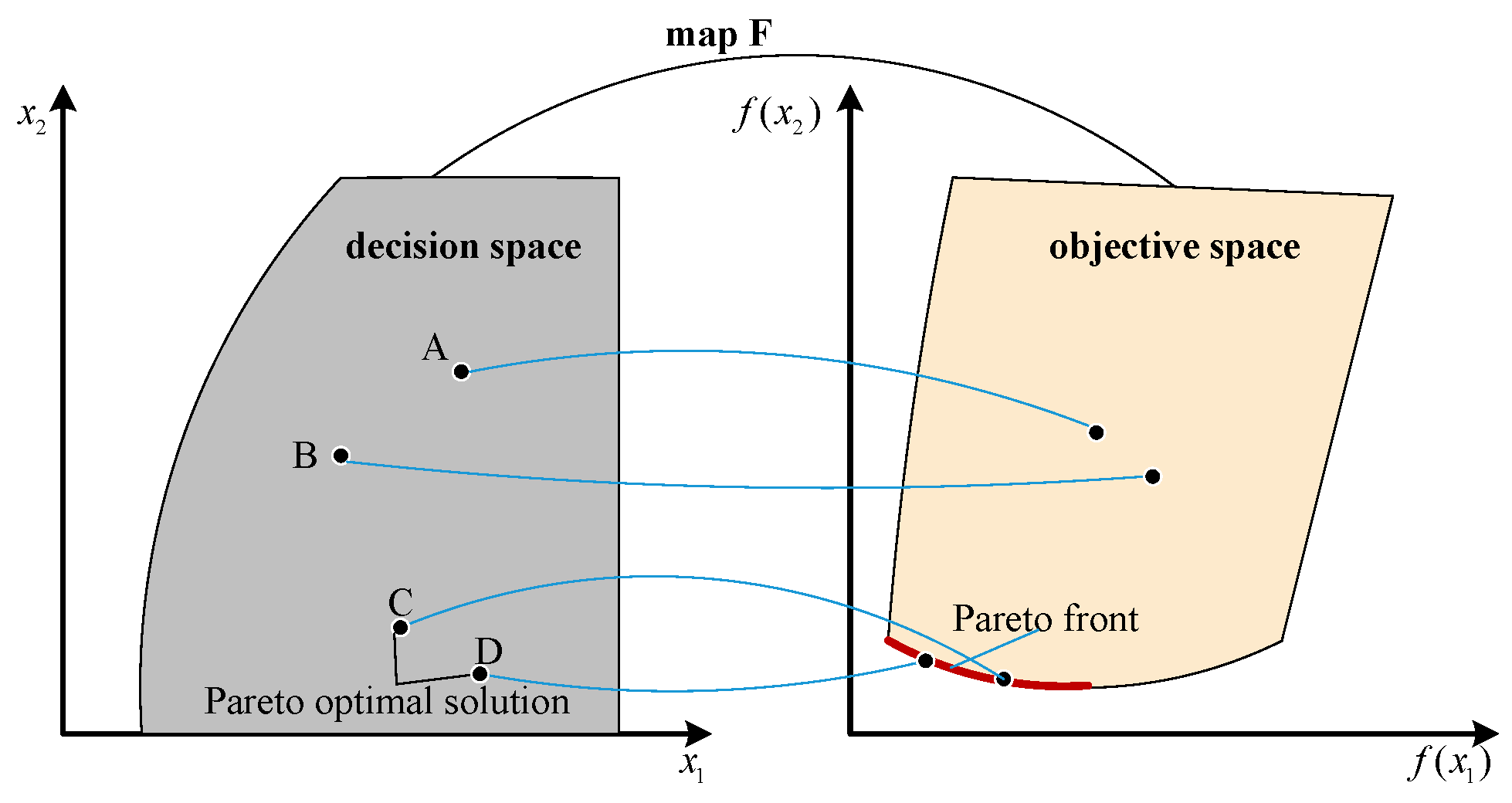

As computational simulations and data-driven modeling have become critical research tools, practical optimization increasingly involves derivative-free objectives from these sources while balancing competing goals. This defines multi-objective derivative-free optimization (DFO) problems, which are prevalent in engineering domains like chemical engineering and steel metallurgy. A general multi-objective DFO problem can be formulated as follows:

where

is an

n-dimensional decision vector within the feasible decision set

. The corresponding feasible objective set is then defined as the mapping of

under the objective function

. Moreover, the objective function

for

satisfies the following: (i) At least one

is a black-box (derivative-free) function. (ii) For any

, there exists

such that

and

conflict, meaning that no point in

can simultaneously minimize all objectives. This article focuses specifically on the bound-constrained case, i.e.,

where

and

denote element-wise lower- and upper-bound vectors for the decision variable

.

The optimization methods for solving such problems can be broadly classified into three categories: direct search methods, model-based methods, and population-based heuristic methods. Direct search methods generate candidate solutions through systematic geometric sampling patterns, as exemplified in [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Model-based methods, also referred to as surrogate-based methods, construct approximation models from evaluated points and generate new candidates by optimizing these surrogates, often embedded within trust-region frameworks [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Population-based heuristic algorithms, which simulate evolutionary processes or collective behaviors within solution sets to generate candidate solutions, have long been commonly used for solving multi-objective DFO problems [

9,

10,

11].

However, such heuristic algorithms typically require a large number of function evaluations and lack mathematical convergence guarantees, making them unsuitable for expensive black-box functions. To mitigate this limitation, surrogate-assisted population-based algorithms have been developed. For instance, ref. [

12] proposed a surrogate-assisted multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with a two-level model management strategy to balance convergence and diversity under a limited evaluation budget. Similarly, ref. [

13] introduced a linear subspace surrogate modeling approach for large-scale expensive optimization, which constructs effective models in high-dimensional spaces using minimal historical data. Additionally, decision variable clustering has been applied to enhance multi-objective optimization (MOO) algorithms in addressing large-scale problems [

14].

Meanwhile, multi-objective DFO methods derived from model-based trust-region frameworks are also attracting growing research attention. For example, building on the scalarization approach in [

15], a DFO method was developed under the trust-region framework for bi-objective optimization problems [

16]. Subsequently, ref. [

17] proposed a direct multi-objective trust-region algorithm for problems where at least one objective is an expensive black-box function. More recently, ref. [

7] presented a modified trust-region approach for approximating the complete Pareto front in multi-objective DFO problems.

Furthermore, directional direct search methods, whose global convergence and computational complexity have been thoroughly characterized [

18,

19], have also been extended to multi-objective DFO. For instance, mesh adaptive search was extended to bi-objective optimization problems, though the uniformity of solution distribution was limited by the design of aggregation functions in pre-decision techniques [

15]. Later, ref. [

20] developed the multi-objective MADS algorithm using the normal boundary intersection (NBI) method and established necessary convergence conditions. However, the construction of convex hulls for individual objective minimization in NBI led to significant sensitivity of MADS performance to convex hull parameters. To address this, ref. [

1] proposed the direct multisearch (DMS) framework, integrating pattern search with mesh adaptive strategies. The original DMS framework did not incorporate a search step. To overcome this limitation, ref. [

21] developed the BoostDMS algorithm, which enhances performance through the integration of a model-based search step. Building upon this, ref. [

22] further extended the framework to a parallel multi-objective DFO algorithm that unifies both search and poll steps. To tackle challenges from local optima in multi-modal problems, ref. [

2] introduced multi-start strategies into algorithm design. Inspired by [

2,

23], ref. [

3] proposed a novel mesh adaptive search-based optimizer to improve convergence properties. For better handling of nonlinear constraints in multi-objective DFO, ref. [

24] replaced the extreme barrier constraints in DMS with a filter strategy incorporating inexact feasibility restoration. Additionally, to improve computational efficiency in practical applications, ref. [

4] established an adaptive search direction selection mechanism, validated through numerical experiments on benchmark functions and automotive suspension design.

This article presents a multi-objective DFO algorithm designed to approximate the complete Pareto front within a limited function evaluation budget. The proposed algorithm, developed within the DMS framework and denoted as DMSCFSM, incorporates sparse modeling and a novel non-dominated comparison function technique. It integrates several strategies from previous works, including the use of previously evaluated points for surrogate model construction [

21], the building of both incomplete and complete models [

25], the generation of positively spanning search directions [

1], and a Pareto dominance-based comparison mechanism [

26].

Inspired by [

25], a sparse modeling approach is adopted in the search step to formulate surrogate models. This method plays a crucial role in mitigating the curse of dimensionality and differs from the modeling strategy employed in [

21]. Moreover, it has been observed that conventional non-dominated set updates, which rely solely on Pareto dominance, often overlook differences in dominance strength, which is defined as the number of solutions a point dominates within the mutually non-dominated set. This oversight can result in retaining solutions with weak dominance strength, making them vulnerable to replacement by new non-dominated points in subsequent iterations. To address this issue, a new comparison function is introduced in the proposed algorithm. A detailed description of DMSCFSM is provided in

Section 3.

The structure of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the preliminaries. The modified algorithm is elaborated in

Section 3.

Section 4 delves into numerical results and the experimental implementation of the method, which includes a comparison of the algorithm’s numerical performance with state-of-the-art algorithms. Finally, conclusions are provided in

Section 5.

3. Proposed Algorithm Description

In this section, the proposed model-search DFO algorithm is presented, along with a detailed description of the surrogate modeling method for the search step, a definition of the Pareto dominance-based comparison function, and a comprehensive outline of the complete algorithmic framework.

3.1. Surrogate Modeling Method for Search Step

In this article, the model construction approach is consistent with that employed in trust-region model-based algorithms. Without loss of generality, one objective function

(denoted as

) is considered to illustrate the surrogate modeling approach. In trust-region model-based algorithms, obtaining each iteration step requires finding a solution to the following subproblem:

where

, and

denotes the trust-region radius at the k-th iteration. Here,

and

are the gradient and the approximate Hessian of

, respectively, which are obtained from the surrogate model

.

The quadratic polynomial surrogate models are formulated using selected historical points from the evaluation cache to compute

and

. The model may be either an incomplete or a complete quadratic approximation, depending on the number of available evaluated points. Let

represent the sample set filtered from the cache, where the objective functions

have been evaluated. Each point

in this set is defined as

. Define

as a basis for the polynomial space

(degree

polynomials in

), where

is the space dimension. The

model can be formulated as

The interpolation conditions

lead to the following linear system (

7):

where

is the coefficient vector,

contains observed values, and

is the

interpolation matrix with elements

.

For exact interpolation (if ), the matrix must be invertible. However, when , the system becomes either underdetermined (if ) or overdetermined (if ), and a direct solution is not feasible.

When

, the parameter coefficients

can be determined by solving the following least-squares problem (

8):

By taking the partial derivatives with respect to

and setting them to zero, the following system of Equation (

9) is obtained:

If has full column rank, then is non-singular.

When

, a Dantzig selector approach is employed to construct the surrogate model, which possesses the oracle properties [

28]. This method differs from the surrogate modeling technique presented in [

21], while offering variable selection capabilities for handling sparse optimization problems. The resulting parameter estimation problem leads to the non-smooth convex optimization problem (

10).

where

is a tolerance parameter whose selection affects the accuracy of the predictive model [

28] and influences the algorithm’s performance. Adaptive selection is required when solving different problems. In this article, it was uniformly set to

eps during the numerical experiments. Problem (

10) is an NP-hard optimization problem. Motivated by the well-established theoretical guarantees of linear programming, this issue is addressed by reformulating the problem (

10) in the form of (

11) by introducing non-negative variables

and

. Alternatively, problem (

10) can also be solved directly by other methods, such as the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) [

29] and basis-pursuit denoising [

30].

where

with

and

. And

,

denotes the all-ones vector of dimension

. Moreover,

and

.

Algorithm 1 outlines the pseudocode for constructing quadratic surrogate models, from which

(gradient) and

(approximate Hessian) are derived. The trial points are then obtained by solving the trust-region subproblem (

5), which minimizes the surrogate model within the current-iteration trust region.

| Algorithm 1 Surrogate model construction |

- Require:

Evaluated points with function values ; Dimension n - Ensure:

Gradient and Hessian - 1:

dimension of decision space - 2:

- 3:

( represents the number of samples in the sample set Y) - 4:

if then - 5:

Form interpolation matrix with basis - 6:

Solve from Equation ( 7) via SVD - 7:

else if then - 8:

Solve from Equation ( 9) via SVD - 9:

else if then - 10:

Solve from from linear program ( 11) via to get (where ) - 11:

Derive from (coefficients of linear terms in ) - 12:

Derive from (coefficients of quadratic terms in ) - 13:

return and for constructing subproblem

|

3.2. Pareto Dominance-Based Comparison Function

Let and denote the initial point and the corresponding step-size parameter, respectively. Let be the list of non-dominated points along with their corresponding step-size parameters, where . Define as the set of new candidate points and their step-size parameters generated during the k-th iteration. Now suppose and are two points in that are mutually non-dominated with respect to the points in , but dominates more points in than does. According to the principle of Pareto dominance, both and would typically be added to the updated non-dominated list . However, in practice, is more likely to be dominated by other points in subsequent iterations. This information is overlooked when selecting non-dominated points solely based on Pareto dominance.

To address this issue, a Pareto dominance-based comparison function

is proposed, defined as follows:

where

and

are two feasible candidate points that are non-dominated with respect to points in

. The function

is defined as Equation (

13).

where

is the set of solutions in

dominated by

, and

denotes set cardinality.

Based on Equation (

12), the comparison function

determines which candidate point are incorporated into the current non-dominated set

to form

: when

and

, the set is updated as

; if, instead,

, then

, whereas when

, the update becomes

.

3.3. The General Framework of the DMSCFSM Algorithm

DMSCFSM operates within the DMS framework. The algorithm begins with an initialization phase, and then enters an iterative cycle of search and poll steps. This iteration continues until a stopping or convergence criterion is met. At the

k-th iteration, the algorithm aims to refine the approximate Pareto front

. The complete procedure is formalized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 DMSCFSM Algorithm Framework |

- 1:

Initialization: - 2:

Parameters initialization: Set initial step size , contraction coefficients , expansion coefficient , and define as the set of positive spanning sets. Generate initial sample points using LHS. Initialize iteration counter , cache , candidate set , and success flag . - 3:

Feasible point evaluation and non-dominated solution identification: Filter feasible points within the domain, evaluate while updating . Set function evaluation counter . Compute the non-dominated solution set . - 4:

Non-dominated list construction: Initialize the non-dominated solution list as - 5:

Main Loop: - 6:

while or do - 7:

Sort the points in in descending order according to their projected gaps across all dimensions of the objective space, and select the top-ranked point as the polling center . - 8:

Search Step: - 9:

Set , , - 10:

for do - 11:

Construct quadratic model using the data points in - 12:

while and do - 13:

Define all combinations of l quadratic polynomial models from the total set of m models, , - 14:

for to and do - 15:

Compute by solving problem ( 14), where the set I is defined as the polynomial models corresponding to combination j. - 16:

Update , - 17:

Evaluate - 18:

Update , - 19:

non-dominated subset of - 20:

if then - 21:

Update - 22:

Update - 23:

Replace with in - 24:

Update , - 25:

if then - 26:

Poll Step: - 27:

Choose a positive spanning set from the set - 28:

- 29:

for each do - 30:

- 31:

if then - 32:

Evaluate - 33:

Update , , - 34:

- 35:

if then - 36:

- 37:

else - 38:

- 39:

Replace with - 40:

Return

|

It is important to note that the search step is executed only after the poll step has been performed. During the initialization phase, Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) is conducted to generate the initial non-dominated set

and a cache set

. Additionally, the non-dominated set

is defined as

Within the main loop, the algorithm iterates until either the stopping condition

or the convergence condition

is satisfied, where

denotes the vector of step sizes corresponding to all non-dominated points in

during the

k-th iteration. In the search step, for the MOO problem (

1), surrogate models

are constructed for each objective function

at the

k-th iteration using the method described in

Section 3.1. Pareto non-dominated solutions are then obtained by optimizing a subset of these objective functions, formulated as the single-objective optimization problem (

14):

where

is a selected subset of objective function indices. Let

; then, the trust-region radius threshold is given by

. In the numerical experiments, the parameters are set as

and

. The number of objective functions to be minimized simultaneously depends on the cardinality of the selected subset

I. For a fixed cardinality

, the number of possible combinations is given by

. For a detailed description of the combination strategy, readers are referred to Algorithm 2 in [

21]. The main framework of the search step is presented in Lines 9–24 of Algorithm 2.

The poll step is activated when the search step fails to yield non-dominated solutions. It performs structured exploration around the current poll center using a positive spanning set to discover candidate points that may lead to improvement. First, a positive spanning set is selected from a predefined collection . For each direction , a candidate point is generated via . Following the extreme barrier approach, only points lying within the feasible region are retained for evaluation. Each feasible candidate is then evaluated using the objective function . All evaluated points are added to a cache set . From these, points dominated by the current non-dominated solution set are filtered out, resulting in a set of non-dominated candidates . If is non-empty, define . To facilitate implementation, the first element of is selected as the new poll center . Points in that are dominated by are then removed to obtain , and the non-dominated set is updated as .

For updating the step-size parameter, the adjustment follows the strategy outlined in references [

1,

21]. While this method ensures numerical stability and has proven effective across various problems, adaptive step-size adjustment remains a promising area for further research.

5. Conclusions

Multi-objective DFO plays a significant role in real-world applications, as the accurate resolution of such problems provides crucial support for decision-making processes. However, in many practical optimization scenarios, particularly those involving computationally expensive simulations, objective function evaluations tend to be extremely time-consuming. This underscores the importance of obtaining high-quality Pareto fronts with limited function evaluations.

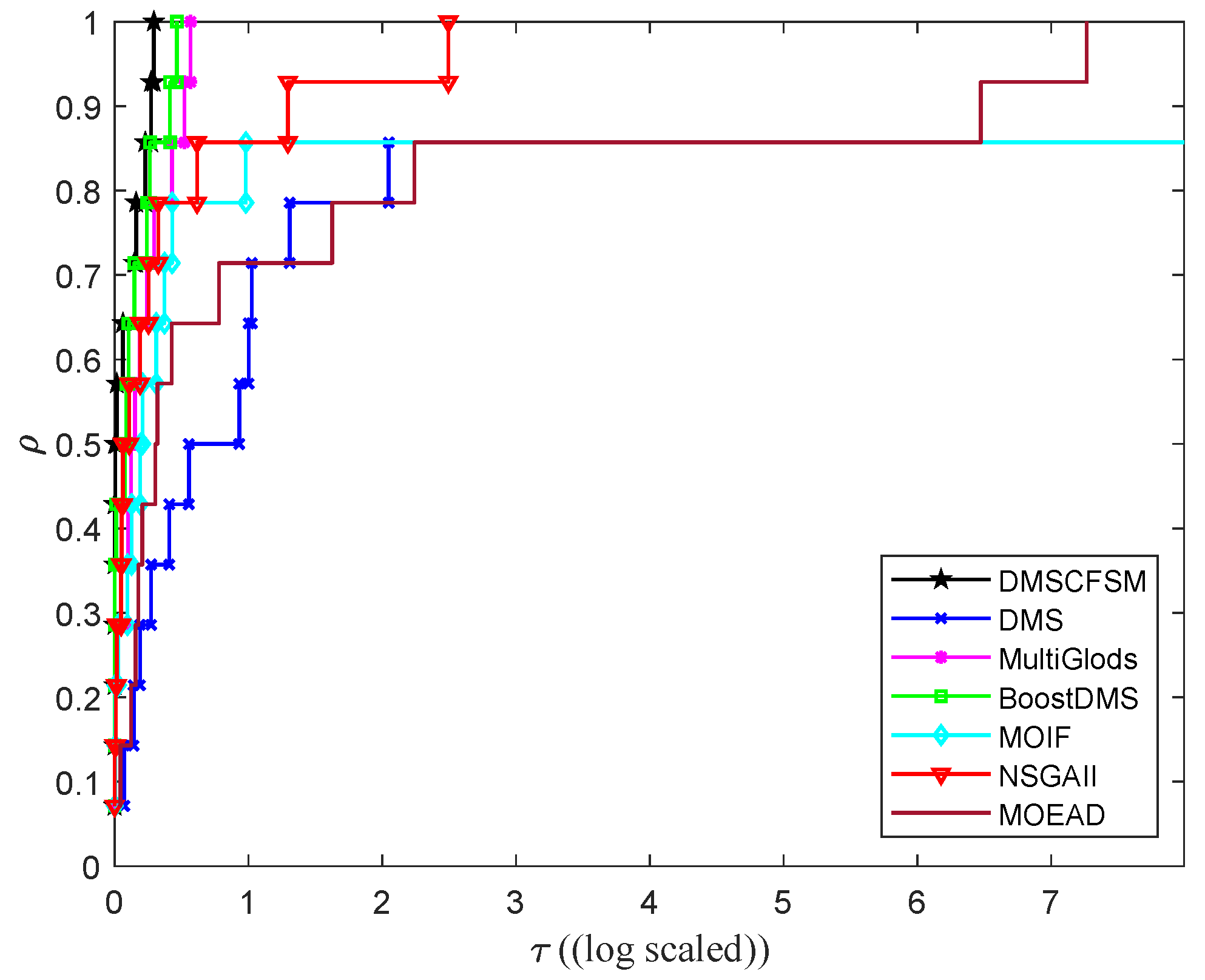

This article presents a novel multi-objective DFO method developed within the DMS framework. The proposed algorithm incorporates two key improvements. The first is the application of a sparse modeling technique for surrogate model construction. The second is the implementation of a Pareto dominance-based comparison function to fully utilize non-dominated solution information. To assess algorithmic performance, comprehensive comparisons were conducted with six state-of-the-art algorithms using ZDT and WFG benchmark problems. Numerical experiments demonstrate that the proposed method achieves high-quality Pareto fronts with competitive performance and efficiency. However, the incorporation of comparison functions introduces additional computational costs, which may limit the algorithm’s applicability in certain scenarios. To assess the practical impact of this limitation, future work is required to evaluate its performance on more complex, high-dimensional problems and real-world engineering problems that are computationally expensive. Additionally, the algorithm’s performance is influenced by several parameters, such as the step-size update parameters ( and ) and the tolerance (). Therefore, future research will also focus on enhancing the algorithm’s adaptive capabilities to reduce this dependency on manual parameter tuning.