Study on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Microscopic Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Nano-SiO2/CTAB System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Modified Nanoparticles

2.2.2. Characterization Method

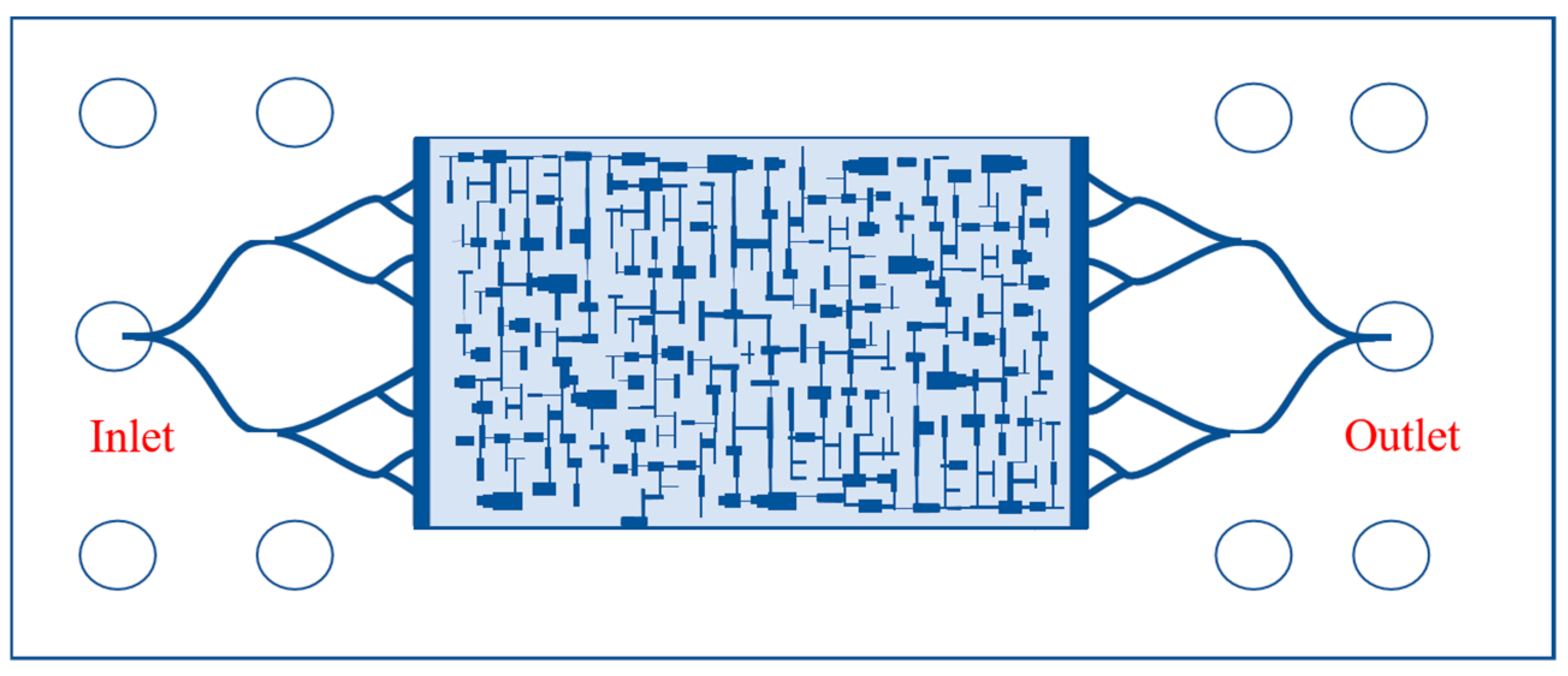

2.2.3. Oil Displacement Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

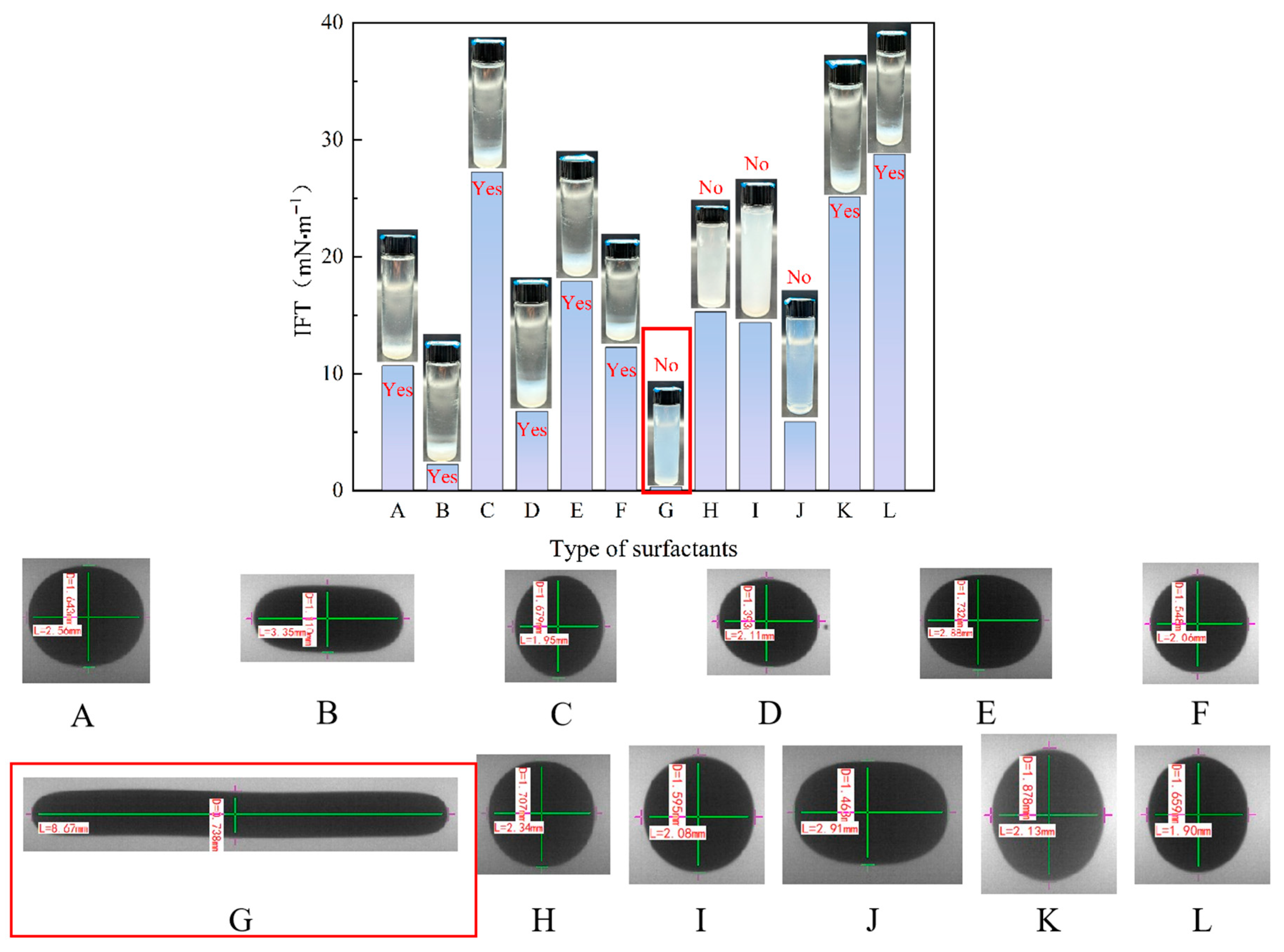

3.1. Preferred Surfactants

3.2. Characterization of Nano-SiO2

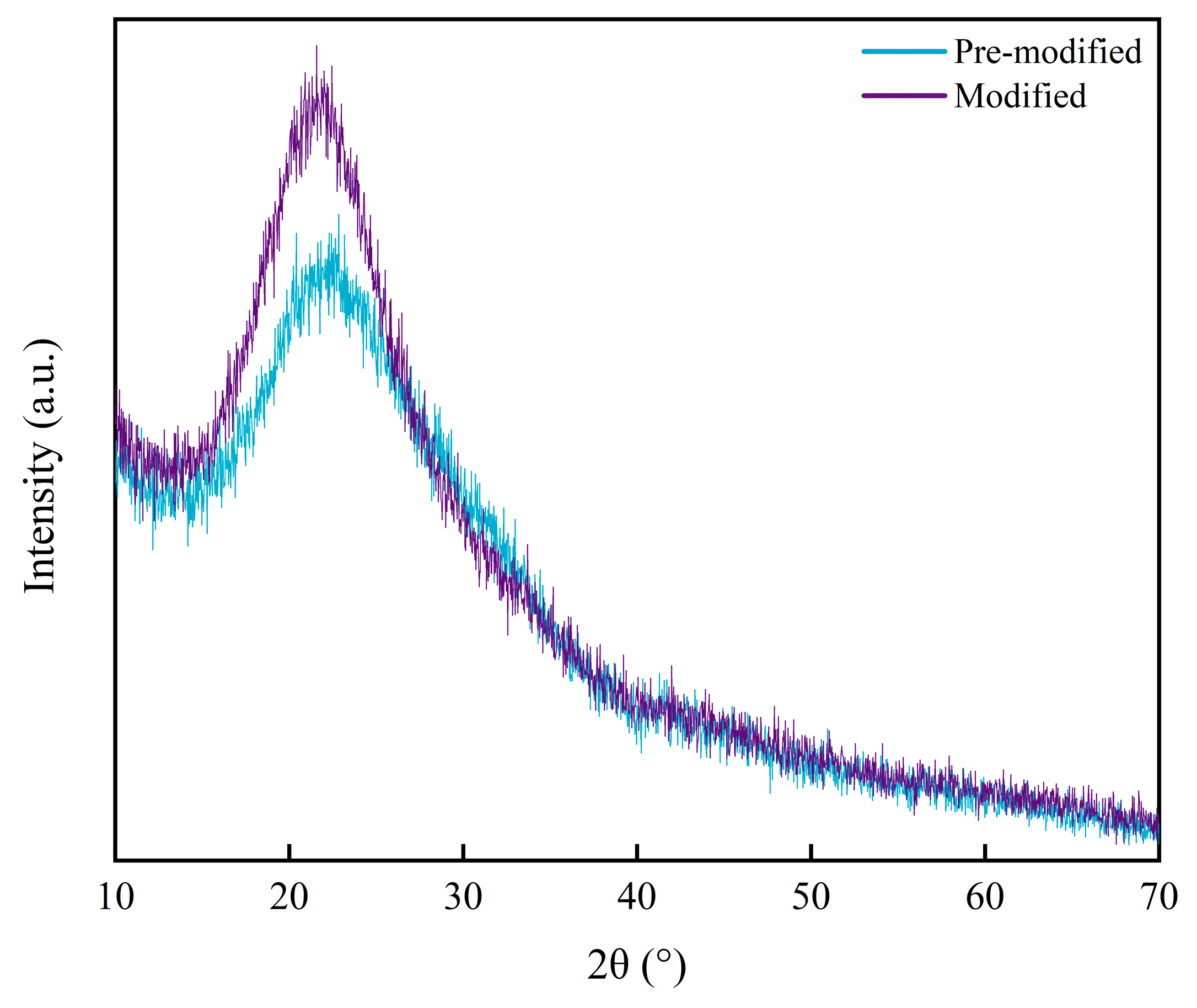

3.2.1. XRD

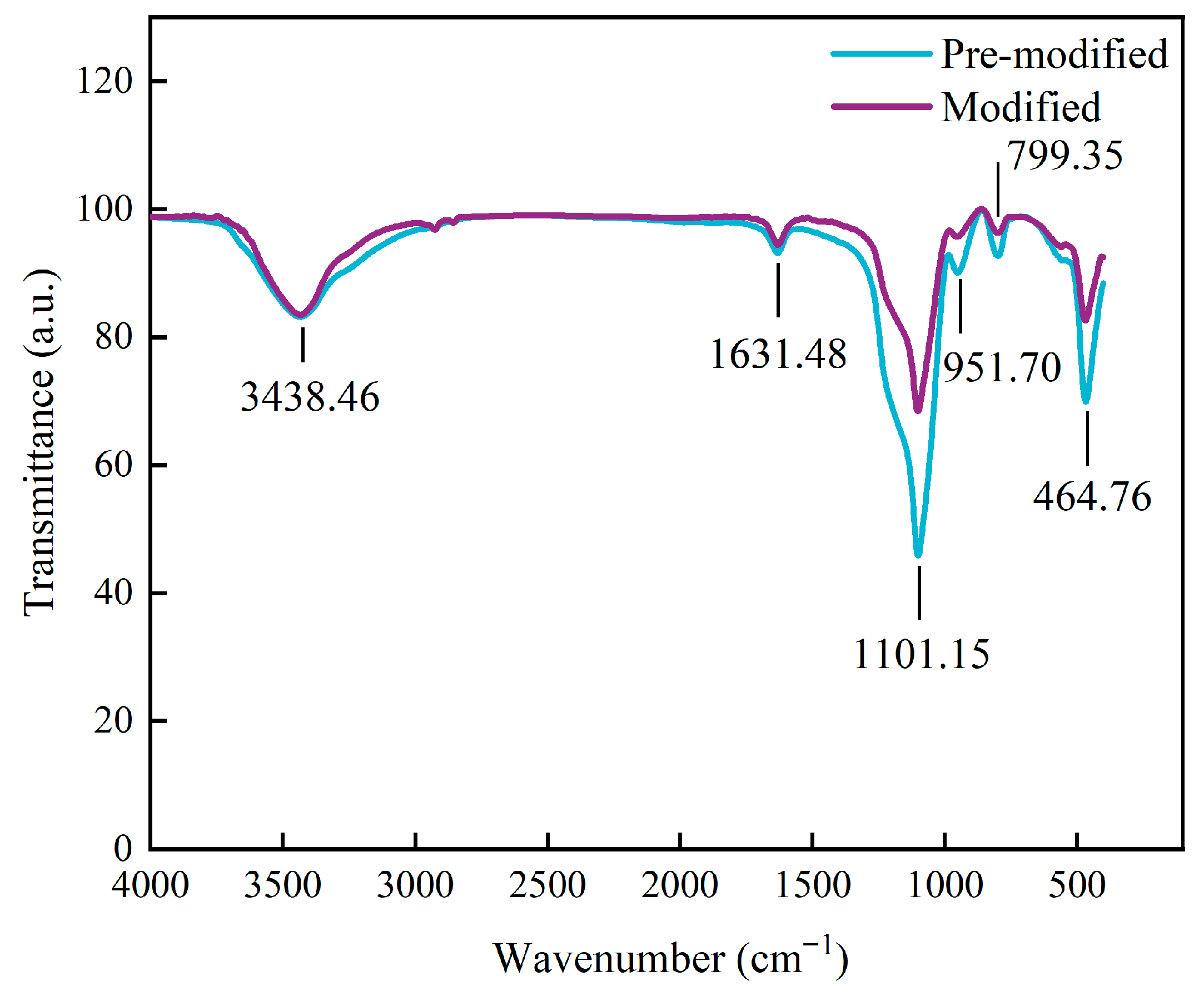

3.2.2. FT-IR

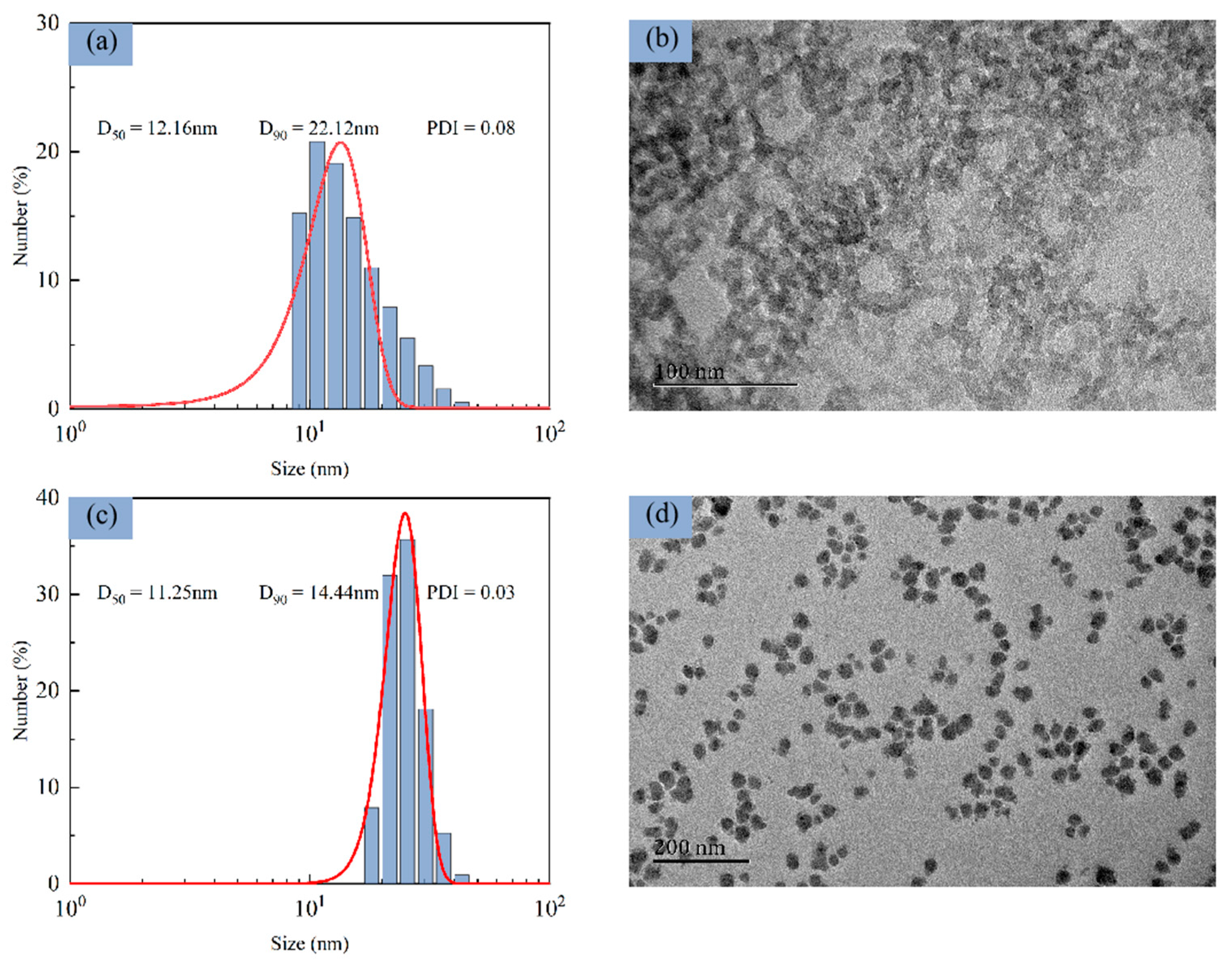

3.2.3. Particle Size and Shape

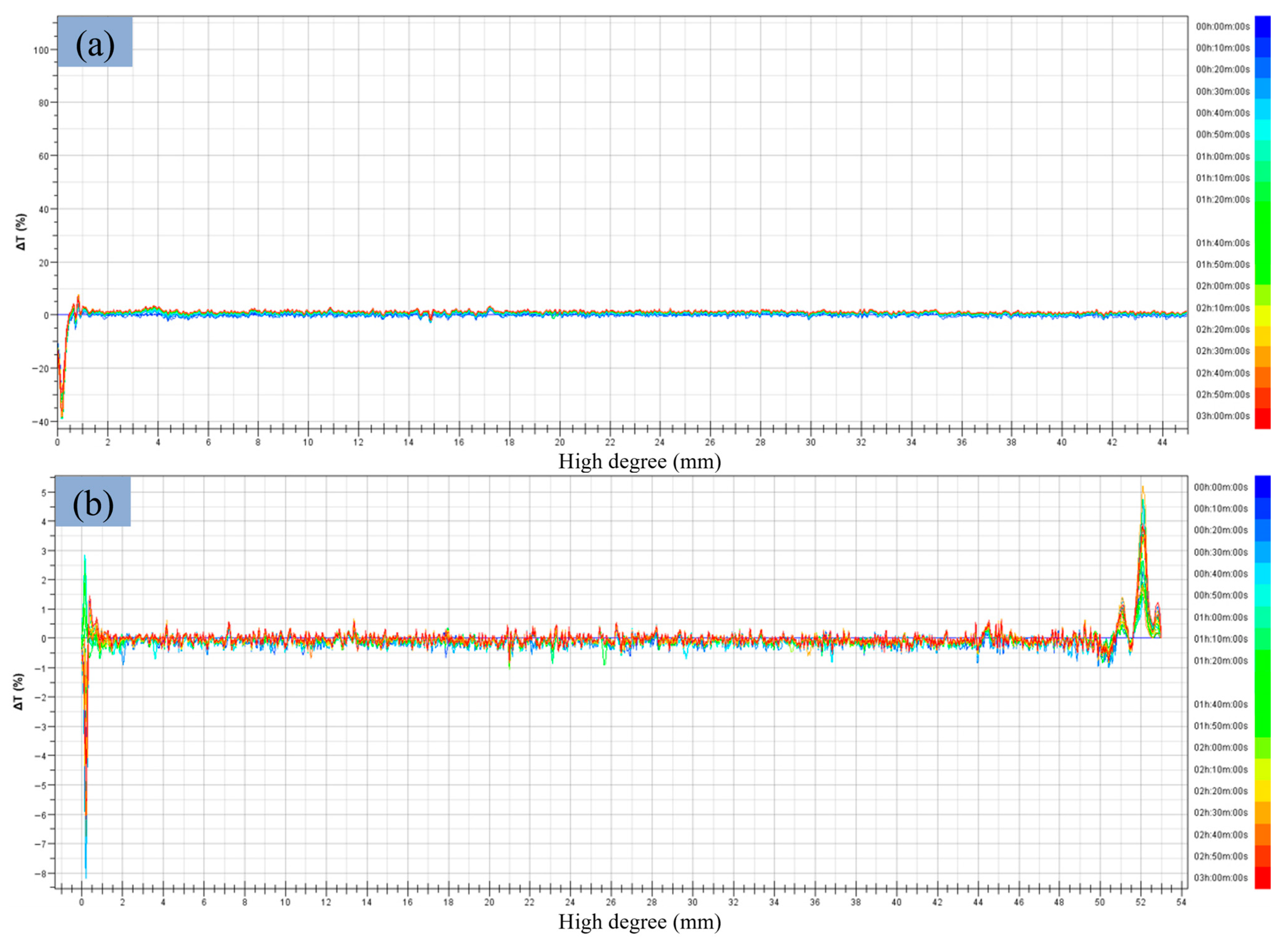

3.2.4. Stability Analysis

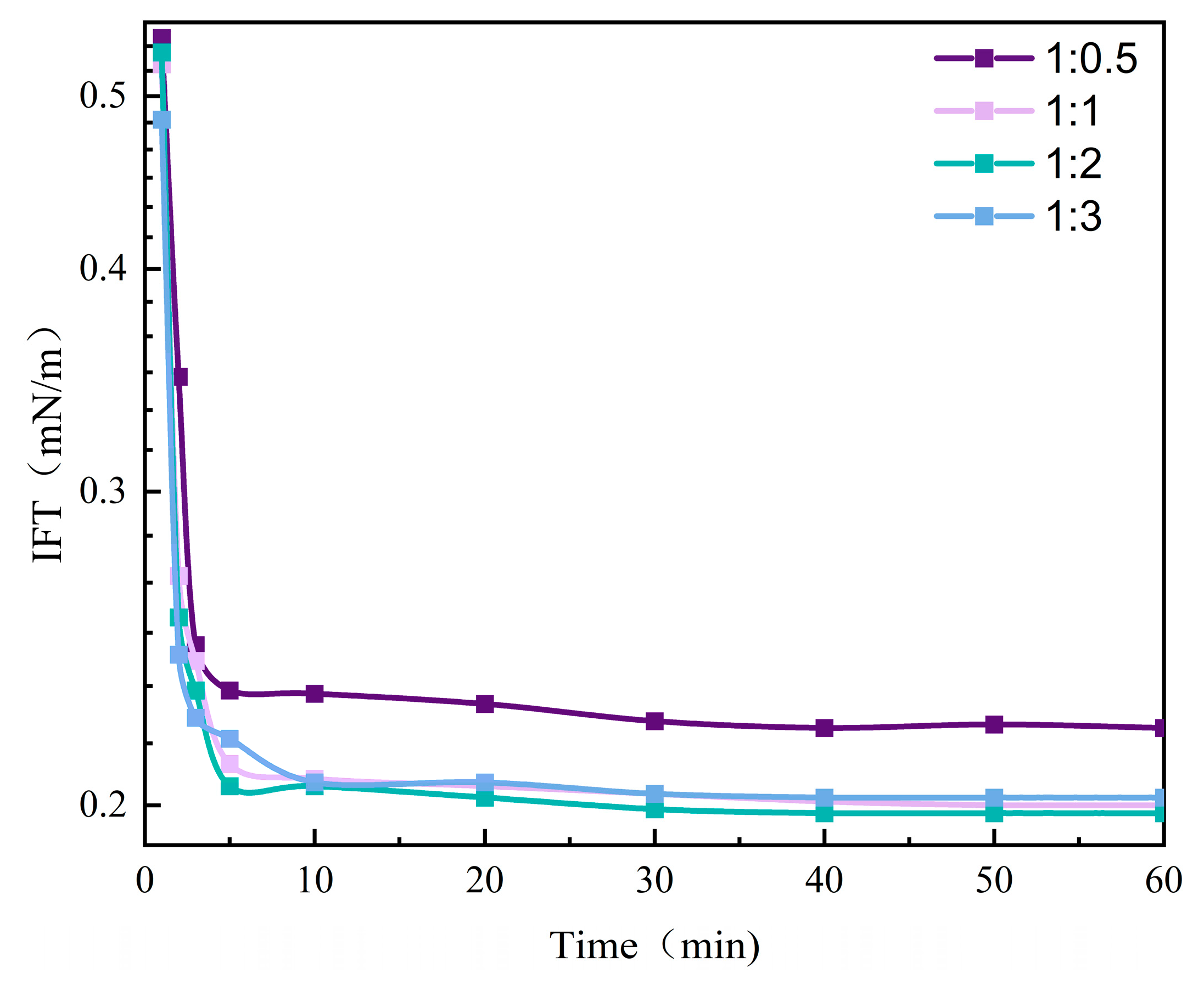

3.3. IFT

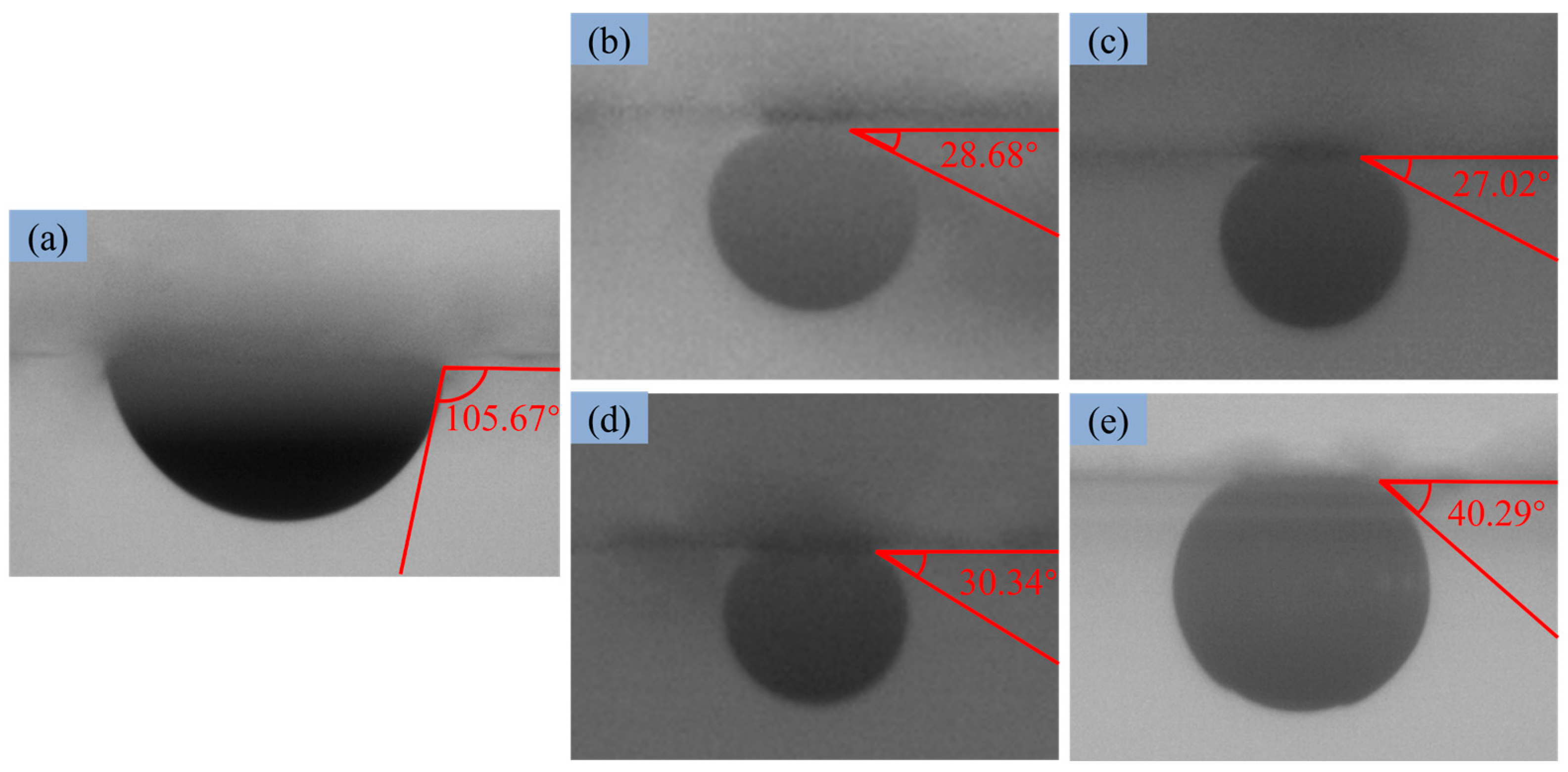

3.4. Wettability

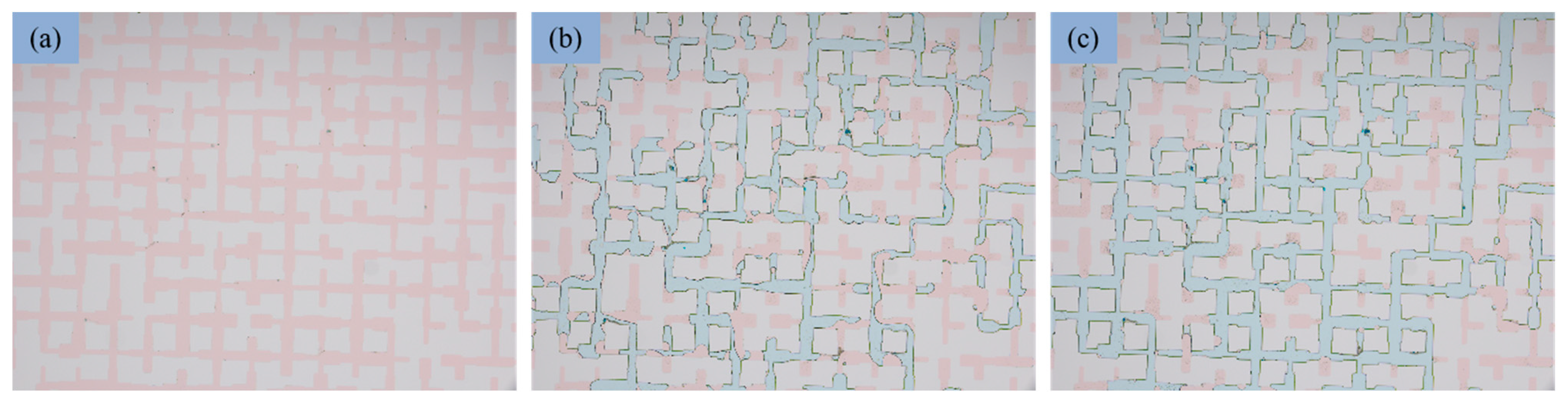

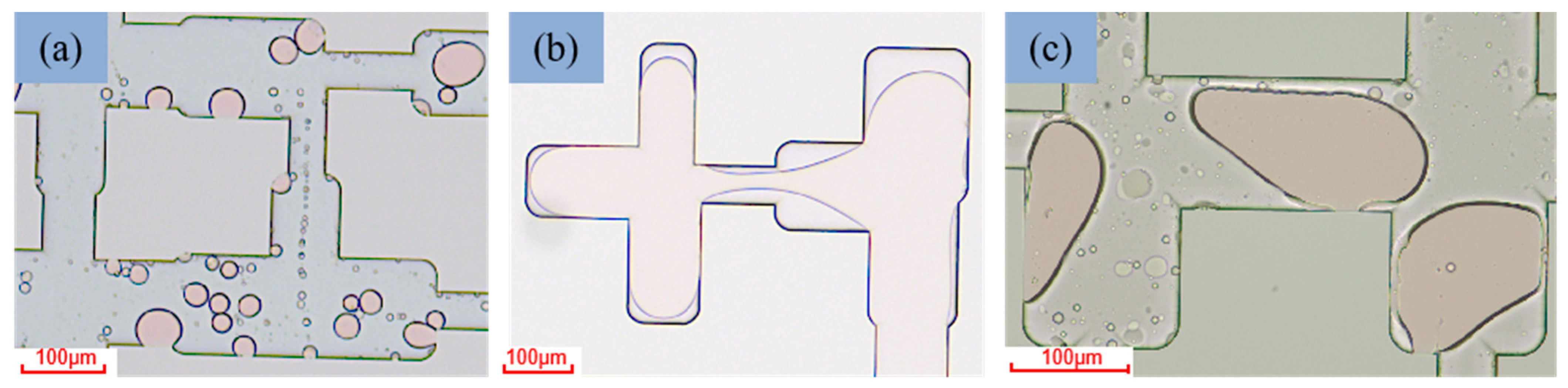

3.5. Mechanism of Oil Displacement

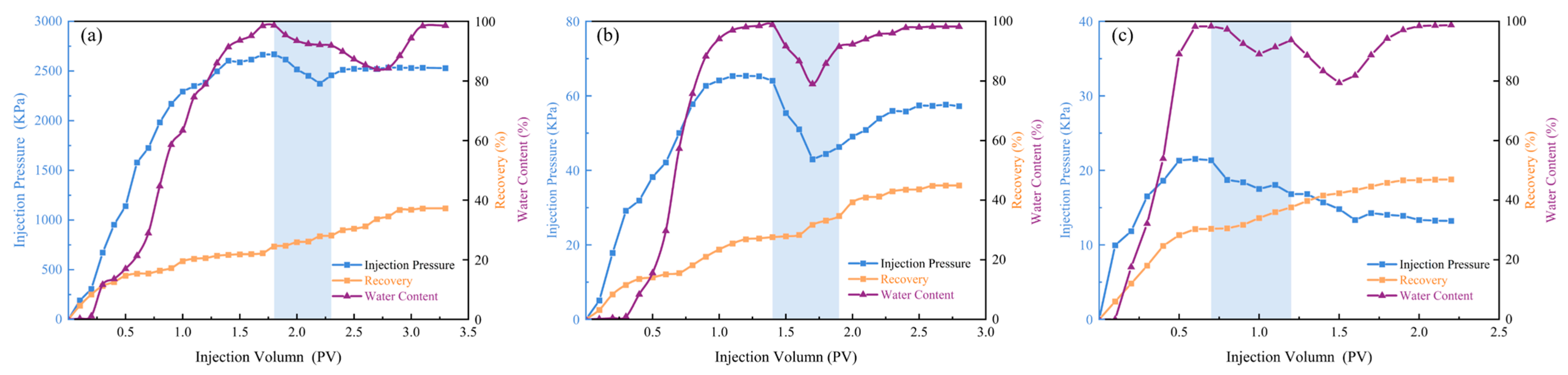

3.6. Evaluation of Oil Displacement Effect

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bera, A.; Belhaj, H. Application of nanotechnology by means of nanoparticles and nanodispersions in oil recovery—A comprehensive review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 1284–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.R.; Tan, R.; Hong, S.P.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, B.-Y.; Chang, J.-W.; Luan, T.-F.; Kang, N.; Hou, J.-R. Synergistic anionic/zwitterionic mixed surfactant system with high emulsification efficiency for enhanced oil recovery in low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinmei, B.; Kun, Q.; Xiangji, D.; Yanfeng, H. Experimental study of surfactant flooding system in low permeability reservoir. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Su, Y.L.; Li, L.; Meng, F.-K.; Zhou, X.-M. Characteristics and mechanisms of supercritical CO2 flooding under different factors in low-permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yue, P.; Wang, Q.L.; Yu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, Q.; Li, X. Experimental study of oil displacement and gas channelingduring CO2 flooding in ultra—Low permeability oil reservoir. Energies 2022, 15, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Yu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, Q.; Li, X. Effects of crosslinking agents and reservoir conditions on the propagation of fractures in coal reservoirs during hydraulic fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, C.; Ning, Y.; Wang, X. Preparation and application of nanofluid flooding based on polyoxyethylated graphene oxide nanosheets for enhanced oil recovery. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 247, 117023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.Y.; Li, Z.C.; Neilson, B.M.; Lee, W.; Huh, C.; Bryant, S.L.; Bielawski, C.W.; Johnston, K.P. Effect of adsorbed amphiphilic copolymers on the interfacial activity of superparamagnetic nanoclusters and the emulsification of oil in water. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5157–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yi, W.Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Du, Q. Janus graphene oxide nanosheets prepared via Pickering emulsion template. Carbon 2015, 93, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Qamar, S.F.; Das, S.; Basu, S.; Kesarwani, H.; Saxena, A.; Sharma, S.; Sarkar, J. Advanced multi-wall carbon nanotube-optimized surfactant-polymer flooding for enhanced oil recovery. Fuel 2024, 355, 129463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H.; Baig, M.M.; Yahya, N.; Khodapanah, L.; Sabet, M.; Demiral, B.M.; Burda, M. Impact of carbon nanotubes based nanofluid on oil recovery efficiency using core flooding. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Babadagli, T. Wettability alteration: A comprehensive review of materials/methods and testing the selected ones on heavy-oil containing oil-wet systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 220, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manshad, A.K.; Rezaei, M.; Moradi, S.; Nowrouzi, I.; Mohammadi, A.H. Wettability alteration and interfacial tension (IFT) reduction in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) process by ionic liquid flooding. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 248, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Viguerie, L.D.; Laporte, L.; Berraud-Pache, R.; Zhuang, G.; Souprayen, C.; Jaber, M. Oily bioorganoclays in drilling fluids: Micro and macroscopic properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 247, 107186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roustaei, A.; Saffarzadeh, S.; Mohammadi, M. An evaluation of modified silica nanoparticles’ efficiency in enhancing oil recovery of light and intermediate oil reservoirs. Egypt. J. Pet. 2013, 22, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.H.; Pu, H. Molecular simulation study of interfacial tension reduction and oil detachment in nanochannels by Surface-modified silica nanoparticles. Fuel 2021, 292, 120318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhuo, S.Q.; Li, S.Z.; Yin, N.; Luo, C.; Ren, H.; Jia, M.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Q. Wettability modification of a nano-silica/fluoro surfactant composite system for reducing the damage of water blocking in tight sandstone reservoirs. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 5264–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Saaid, I.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Pilus, R.M.; Baig, M.K. Evaluating the potential of surface-modified silica nanoparticles using internal olefin sulfonate for enhanced oil recovery. Pet. Sci. 2019, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Cheng, T.T.; Fu, C.; Huang, B.; Yang, E.; Qu, M.; Liu, S.; Wu, J. Synthesis and characterization of self-dispersion monodisperse silica-based functional nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) in low-permeability reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, W.; Chen, Y. Preparation and characterization of modified amphiphilic nano-silica for enhanced oil recovery. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 633, 127864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Ge, H.; Li, D.; Cao, Y.; Sun, D. Nanofluid of amphiphilic carbon nitride nanosheets for enhanced oil recovery. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 721, 137206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakov, A.V.; Pryazhnikov, M.I.; Zhigarev, V.A.; Rudyak, V.Y.; Filimonov, S.A. Numerical study of the mechanisms of enhanced oil recovery using nanosuspensions. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2021, 35, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 sequestration to hydrogen storage: Further utilization of depleted gas reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Xia, Y.F. Risk prediction of gas hydrate formation in the wellbore and subsea gathering system of deep-water turbidite reservoirs: Case analysis from the south China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.T.; Yang, Z.Q.; Yan, W.D.; Huang, B.; Wu, J.; Yang, E.; Liu, H.; Zhao, K. Impact of the nano-SiO2 particle size on oil recovery dynamics: Stability, interfacial tension, and viscosity reduction. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 15160–15171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calderon, M.; Haase, T.A.; Novikova, N.I.; Wells, F.S.; Low, J.; Willmott, G.R.; Broderick, N.G.; Aguergaray, C. Turning industrial paints superhydrophobic via femtosecond laser surface hierarchical structuring. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 163, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, L.; Mughayyirah, Y.; Amilia; Sudarsono; Zainuri, M. Surface modification of SiO2-based methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS) using cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) on the wettability effects through hierarchical structure. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2023, 108, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Wu, C.M.; Varcoe, J.R.; Poynton, S.D.; Xu, T.; Fu, Y. Novel silica/poly(2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide) hybrid anion-exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: Effect of silica content and the single cell performance. J. Power Sources 2009, 195, 3069–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán, J.; Yon, J.; Henry, C.; Kholghy, M.R. Approximating the van der Waals interaction potentials between agglomerates of nanoparticles. Adv. Powder Technol. 2023, 34, 104269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, T.; Bose, M. Morphological analysis of nanoparticle agglomerates generated using DEM simulation. Part. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Shinohara, K. Experimental equation on intensity of transmitted light through particle suspension of higher concentration. Powder Technol. 2001, 120, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.; Geng-Sheng, J.; Lei, P.; Bao-Lin, Z.; Ke-Zhi, L.; Jun-Long, W. Influences of surface modification of nano-silica by silane coupling agents on the thermal and frictional properties of cyanate ester resin. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.P.; Pu, W.F.; Li, S.Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S. An amphiphilic nano titanium dioxide based nanofluid: Preparation, dispersion, emulsion, interface properties, wettability and application in enhanced oil recovery. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 197, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Wu, J.; Zhao, B. Research on percolation characteristics of a Janus nanoflooding crude oil System in porous media. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23107–23114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Guan, B.; Liu, W.; Chen, B.; Sun, J.; Li, M.; Wu, W.; Hua, S.; Geng, X.; Chen, W.; et al. Mechanism of improving water flooding using the Nanofluid permeation flooding system for tight reservoirs in Jilin oilfield. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 17389–17395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.P.; Xin, Y.; Wei, L.N.; Ding, F.; Gao, Z.; Liu, H.; Tang, M.; Du, X.; Dai, C. Oil drop stretch and rupture behavior at throat and pore junction during imbibition with active nanofluid: A microfluidic approach. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 653, 130012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sun, S.S.; Cui, K.; Li, H.; Gong, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Z. Wettability alteration in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs by “SiO2–rhamnolipid” nanofluid. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 12170–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Nikolov, A.; Wasan, D. Dewetting film dynamics inside a capillary using a micellar nanofluid. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2014, 30, 9430–9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Hou, Z.W.; Wang, H.F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Cui, Z. Synergistic effects between anionic surfactant SDS and hydrophilic silica nanoparticles in improving foam performance for foam flooding. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Y.L.; Liang, S.N.; Bai, B.; Zhang, C.; Xu, N.; Shi, W.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y. Synthesizing dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles to stabilize Pickering emulsions at high salinity and temperature reservoirs. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 687, 133481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Hou, J.R.; Liang, T.; Qi, P. Amphiphilic rhamnolipid molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for oil recovery. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radnia, H.; Rashidi, A.; Nazar, A.R.S.; Eskandari, M.M.; Jalilian, M. A novel nanofluid based on sulfonated graphene for enhanced oil recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, D.; Nikolov, A.D. Spreading of nanofluids on solids. Nature 2003, 423, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.H.; Meng, S.W.; Tao, J.P.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Guan, J.; Fu, H.; Dai, C.; Liu, H. Preparation and application of modified carbon black nanofluid as a novel flooding system in ultralow permeability reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gas Permeability (mD) | Length (cm) | Radius (cm) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 10.452 | 1.256 | 9.89 |

| 2 | 50 | 10.621 | 1.261 | 13.24 |

| 3 | 100 | 10.231 | 1.259 | 17.43 |

| Name | Code Name | IFT/(mN·m−1) | Precipitates |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEO-9 | A | 10.671 | Yes |

| Triton X-114 | B | 2.241 | Yes |

| Tween 80 | C | 27.240 | Yes |

| Triton X-100 | D | 6.776 | Yes |

| Span 80 | E | 17.893 | Yes |

| Brij-35 | F | 12.255 | Yes |

| CTAB | G | 0.300 | No |

| SDS | H | 15.288 | No |

| SDBS | I | 14.376 | No |

| OP-10 | J | 5.885 | No |

| NP-40 | K | 25.119 | Yes |

| AES | L | 28.750 | Yes |

| No. | Gas Permeability (mD) | Primary Water Flooding Recovery (%) | Final Oil Recovery (%) | Enhanced Oil Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 24.72 | 37.23 | 12.51 |

| 2 | 50 | 27.58 | 44.95 | 17.37 |

| 3 | 100 | 30.40 | 46.96 | 16.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Ding, J.; Ren, Y.; Gong, X. Study on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Microscopic Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Nano-SiO2/CTAB System. Processes 2025, 13, 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123862

Cheng T, Wang J, Liu H, Ding J, Ren Y, Gong X. Study on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Microscopic Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Nano-SiO2/CTAB System. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123862

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Tingting, Jinyi Wang, Huaizhu Liu, Jun Ding, Yuting Ren, and Xinhao Gong. 2025. "Study on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Microscopic Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Nano-SiO2/CTAB System" Processes 13, no. 12: 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123862

APA StyleCheng, T., Wang, J., Liu, H., Ding, J., Ren, Y., & Gong, X. (2025). Study on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Microscopic Mechanisms in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Nano-SiO2/CTAB System. Processes, 13(12), 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123862