From Waste to Value: Optimizing Oxidative Liquefaction of PPE and MSW for Resource Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples: Personal Protective Equipment and Municipal Solid Waste

- Moisture (Mad): CEN/TS 15414-2:2010 [22],

- Ash (Aad): EN 15403:2011 (weight method) [23],

- Volatile Matter (VM): EN 15402:2011 (weight method) [24],

- Carbon (Cad), Hydrogen (Ha), Nitrogen (Nad): EN 15407:2011 [25],

- Sulfur (wS,ad): EN 15408:2011 (high-temp. combustion, IR detection) [26],

- Oxygen (Odiff): EN ISO 16993:2016-09 (by difference) [27].

2.2. Oxidative Liquefaction Process

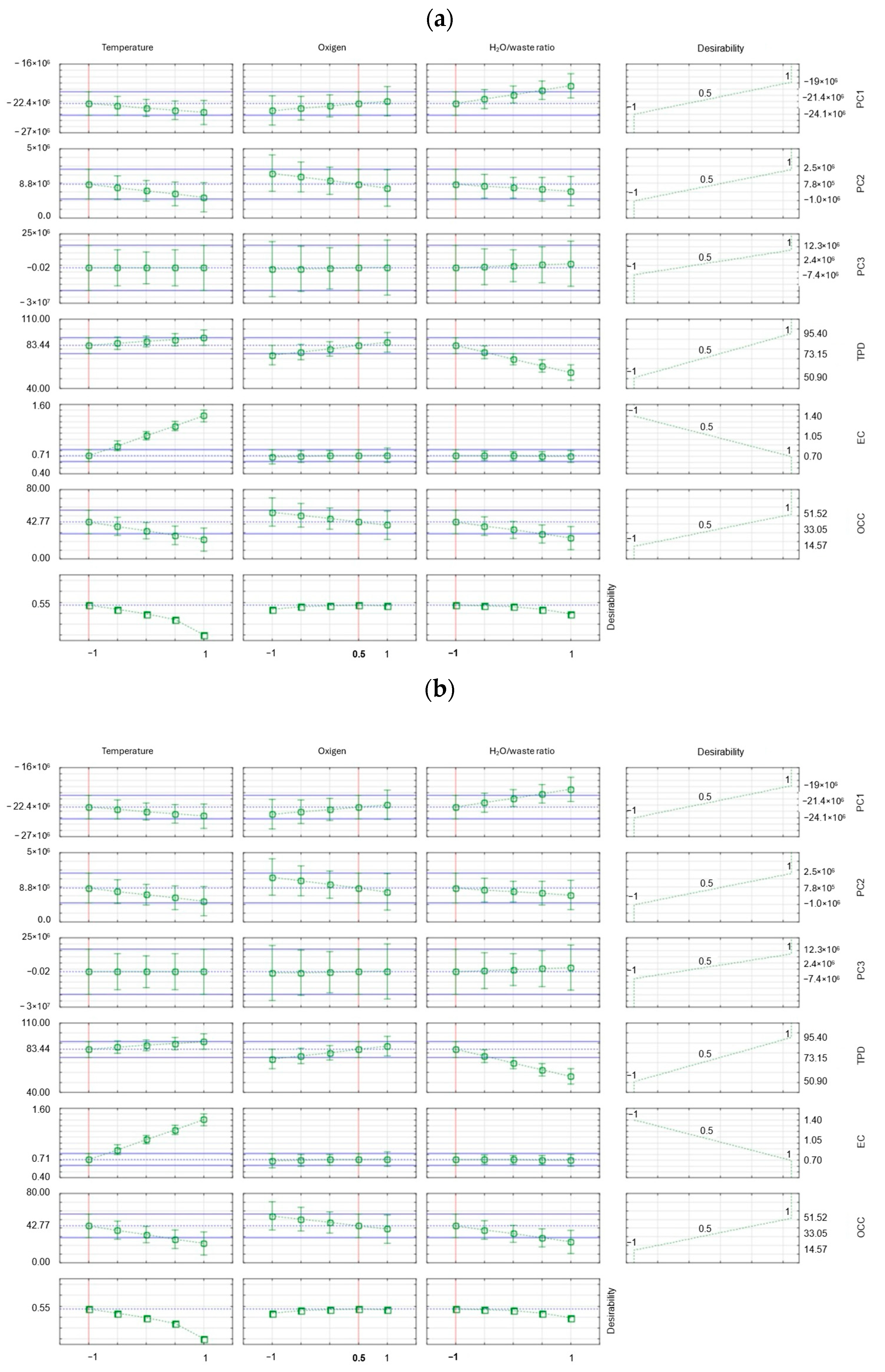

2.3. Design of Experiment (DoE) Plan

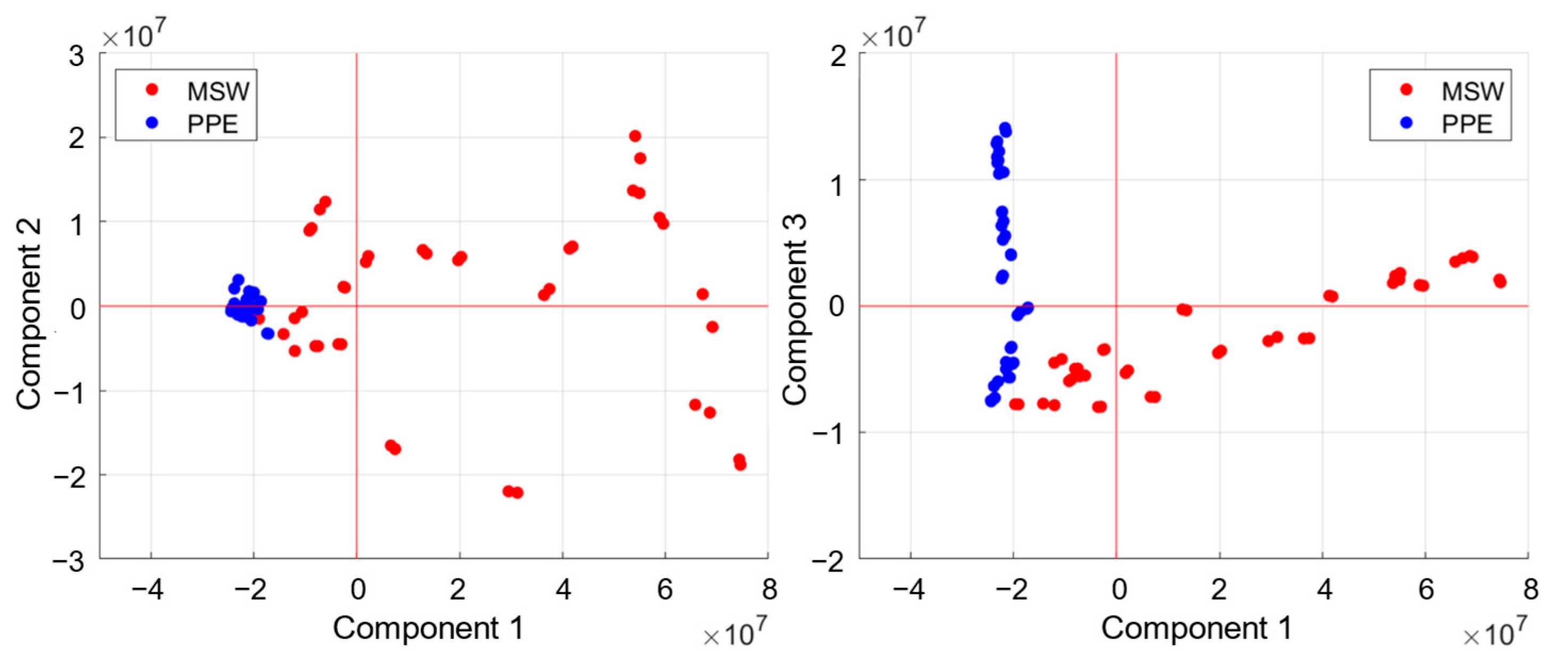

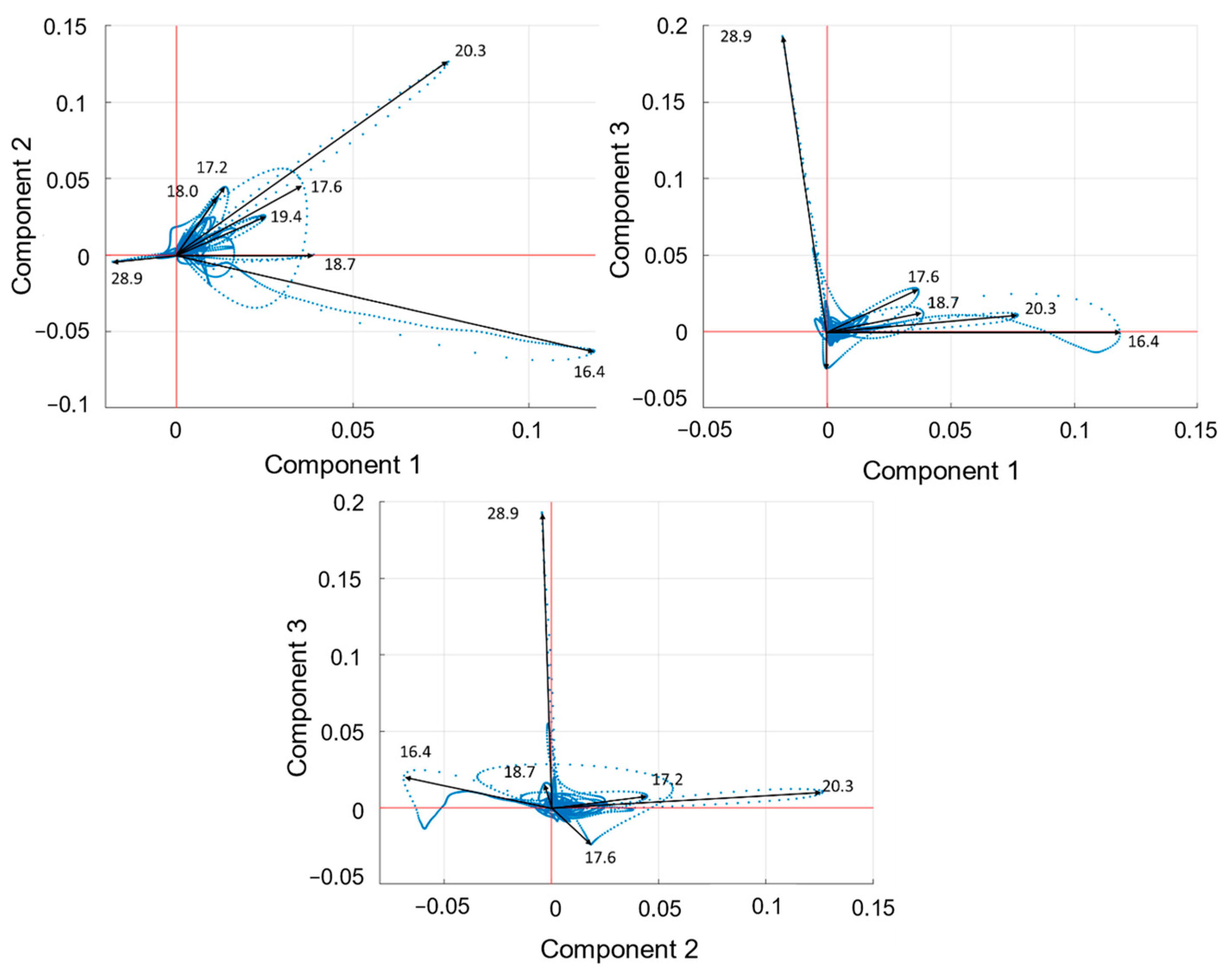

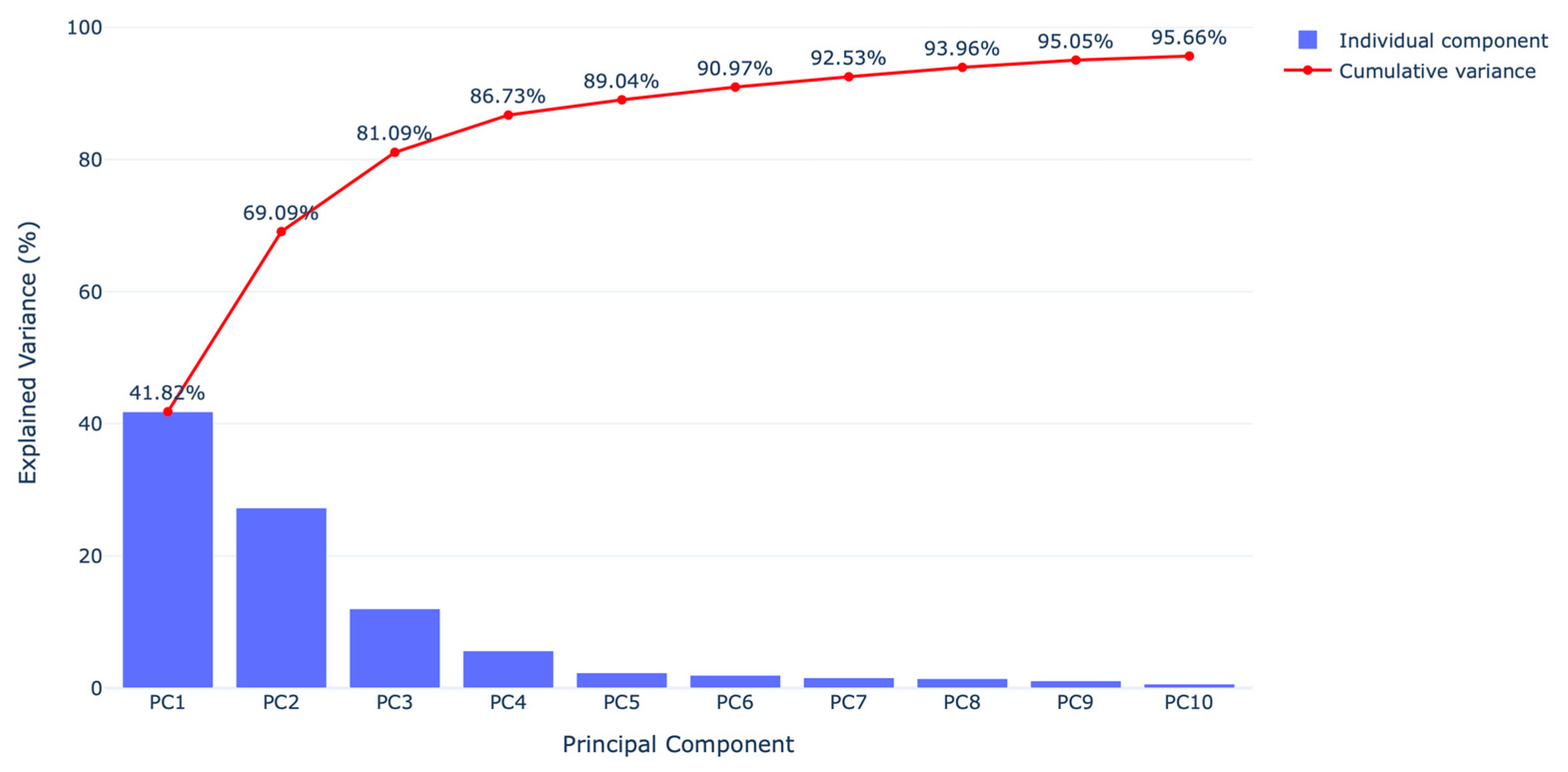

2.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.5. Experimental Procedure

2.6. Liquid Product Analysis

2.7. Preparation of Raw Chromatographic Data

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, X.; Wang, S.; Ni, R.; Song, L. New Insights on Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Landfill Plastisphere Structure and Function. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 888, 163823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R.; Werle, S. Optimizing Advanced Oxidative Liquefaction of Municipal Solid Waste and Personal Protective Equipment of Medical Sector for Solid Reduction and Secondary Compounds Production. Renew. Energy 2025, 255, 123831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Werle, S.; Muzyka, R.; Sobek, S.; Sajdak, M. Oxidative Liquefaction, an Approach for Complex Plastic Waste Stream Conversion into Valuable Oxygenated Chemicals. Energies 2024, 17, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyka, R.; Sajdak, M.; Sobek, S.; Mumtaz, H.; Werle, S. The Application of Chromatographic Methods in Optimization and the Enhancement of the Oxidative Liquefaction Process to Wind Turbine Blade Recycling. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R.; Drewniak, S.; Werle, S. Oxidative Liquefaction as an Alternative Method of Recycling and the Pyrolysis Kinetics of Wind Turbine Blades. Energy 2023, 278, 127950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkki, P.; Rotinen, L.; Taponen, S.; Tella, S.; Grönman, K.; Deviatkin, I.; Pitkänen, L.J.; Venesoja, A.; Koljonen, K.; Repo, E.; et al. Increasing the Role of Sustainability in Public Procurement of Personal Protective Equipment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 455, 142335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID—Coronavirus Statistics—Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Fadare, O.O.; Okoffo, E.D. Covid-19 Face Masks: A Potential Source of Microplastic Fibers in the Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, G.; Mghili, B.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Machendiranathan, M.; Rajeswari, M.V.; Saravanakumar, A. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Pollution Driven by COVID-19 Pandemic in Marina Beach, the Longest Urban Beach in Asia: Abundance, Distribution, and Analytical Characterization. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.T.; Shah, I.A.; Hossain, M.F.; Akther, N.; Zhou, Y.; Khan, M.S.; Al-shaeli, M.; Bacha, M.S.; Ihsanullah, I. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Disposal during COVID-19: An Emerging Source of Microplastic and Microfiber Pollution in the Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.; Calero, M.; Rico, N.; Martín-Lara, M.A. COVID-19 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Contamination in Coastal Areas of Granada, Spain. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, P.; Schartup, A.T.; Zhang, Y. Plastic Waste Release Caused by COVID-19 and Its Fate in the Global Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2111530118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzyniarz, M.; Sajdak, M.; Zajemska, M.; Iwaszko, J.; Biniek-Poskart, A.; Skibíński, A.; Morel, S.; Niegodajew, P. Plastic Waste Management towards Energy Recovery during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Example of Protective Face Mask Pyrolysis. Energies 2022, 15, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smol, M. Is the Green Deal a Global Strategy? Revision of the Green Deal Definitions, Strategies and Importance in Post-COVID Recovery Plans in Various Regions of the World. Energy Policy 2022, 169, 113152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solid Waste Management. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/brief/solid-waste-management (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Tsimnadis, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Arabatzis, G.; Leontopoulos, S.; Zervas, E. An Innovative and Alternative Waste Collection Recycling Program Based on Source Separation of Municipal Solid Wastes (MSW) and Operating with Mobile Green Points (MGPs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakah, N.; Samavati, M.; Akuoko Kwarteng, A.; Martin, A.; Simons, A. Prospects of Waste Incineration for Improved Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Management in Ghana—A Review. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wei, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J. Comparing and Optimizing Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Management Focused on Air Pollution Reduction from MSW Incineration in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R.; Werle, S. An Experimental Investigation and Process Optimization of the Oxidative Liquefaction Process as the Recycling Method of the End-of-Life Wind Turbine Blades. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Werle, S.; Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R. Hydrothermal Treatment of Plastic Waste within a Circular Economy Perspective. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 32, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyka, R.; Mumtaz, H.; Sobek, S.; Werle, S.; Adamek, J.; Semitekolos, D.; Charitidis, C.A.; Tiriakidou, T.; Sajdak, M. Solvolysis and Oxidative Liquefaction of the End-of-Life Composite Wastes as an Element of the Circular Economy Assumptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEN/TS 15414-2:2010—Solid Recovered Fuels—Determination of Moisture Content Using the Oven Dry. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/1f025ad5-653e-4847-8293-2c181d215582/cen-ts-15414-2-2010 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- EN 15403:2011—Solid Recovered Fuels—Determination of Ash Content. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/0c9908dd-e915-4470-b9b9-b7c2011b71fa/en-15403-2011 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- EN 15402:2011—Solid Recovered Fuels—Determination of the Content of Volatile Matter. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/32c296e3-e4fa-443b-a9ae-fafcae85ef14/en-15402-2011 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- EN 15407:2011—Solid Recovered Fuels—Methods for the Determination of Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H) and Nitrogen (N) Content. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/e40c2491-a7b5-4a43-b625-fbcd99146902/en-15407-2011 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- EN 15408:2011—Solid Recovered Fuels—Methods for the Determination of Sulphur (S), Chlorine (Cl), Fluorine (F) and Bromine (Br) Content. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/a161797a-a88d-4fba-9d81-ee017a66c9ec/en-15408-2011 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- EN ISO 16993:2016—Solid Biouels—Conversion of analytical results from one basis to another. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/4907174c-19b5-4570-be8e-9a465733c14d/en-iso-16993-2016 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Gijsman, P. Review on the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polymers during Processing and in Service. E-Polym. 2008, 8, 727–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malaika, S. Oxidative Degradation and Stabilisation of Polymers. Int. Mater. Rev. 2003, 48, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, H.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Mohammed, M.G.; Siddiquee, M.N. Oxidative Depolymerization of Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP) and Polystyrene (PS) Wastes to Value-Added Chemicals. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 242, 111709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, S.; Lombardi, L.; Mendecka, B.; Mumtaz, H.; Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R.; Werle, S. A Life Cycle Assessment of the Laboratory—Scale Oxidative Liquefaction as the Chemical Recycling Method of the End-of-Life Wind Turbine Blades. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable/Coded Values | Temperature, °C | H2O2 Addition, wt.% | Waste-Liquid Ratio, wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 (minimum) | 200 | 30 | 3 |

| 0 (center) | 250 | 45 | 5 |

| 1 (maximum) | 300 | 60 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muzyka, R.; Sajdak, M.; Sobek, S.; Mumtaz, H.; Werle, S. From Waste to Value: Optimizing Oxidative Liquefaction of PPE and MSW for Resource Recovery. Processes 2025, 13, 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123844

Muzyka R, Sajdak M, Sobek S, Mumtaz H, Werle S. From Waste to Value: Optimizing Oxidative Liquefaction of PPE and MSW for Resource Recovery. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123844

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuzyka, Roksana, Marcin Sajdak, Szymon Sobek, Hamza Mumtaz, and Sebastian Werle. 2025. "From Waste to Value: Optimizing Oxidative Liquefaction of PPE and MSW for Resource Recovery" Processes 13, no. 12: 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123844

APA StyleMuzyka, R., Sajdak, M., Sobek, S., Mumtaz, H., & Werle, S. (2025). From Waste to Value: Optimizing Oxidative Liquefaction of PPE and MSW for Resource Recovery. Processes, 13(12), 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123844