Abstract

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) is widely used to promote bone regeneration. However, conventional surface-attached delivery on absorbable collagen sponges causes a rapid burst release, excessive inflammation, and suboptimal healing. To overcome these limitations, we developed a thermally controlled Poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PDLLGA) encapsulation system, designed to stabilize rhBMP-2 and enable controlled release. rhBMP-2 was incorporated in PDLLGA pellets using the hot-melt extrusion of a lyophilized mixture containing poloxamer 407 and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, and terminal sterilization (X-ray irradiation). The released rhBMP-2 maintained its molecular integrity after sterilization and remained stable for up to 732 days in storage, as confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and capillary electrophoresis (CE). Further, high-affinity binding between released rhBMP-2 and BMPR-IA was confirmed by bio-layer interferometry (BLI), and the released protein induced a robust in vitro ALP response, confirming preserved osteogenic activity. Our encapsulation approach for rhBMP-2 using PDLLGA, including the combination product with β-TCP (LDGraft; Locate Bio, Nottingham, UK), provides a stable and bioactive rhBMP-2 delivery strategy with inherent dose-shielding properties, supporting safe, controlled, and effective bone regeneration therapies.

1. Introduction

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) is a potent osteoinductive growth factor [1], widely used to stimulate bone repair [2]. Its clinical use when delivered on absorbable collagen sponges has revealed pharmacokinetic limitations that can impair optimal bone healing [3]. Despite its widespread clinical use, delivery of rhBMP-2 on absorbable collagen sponges suffers from pharmacokinetic limitations, including rapid burst release, low local retention, and the mechanical fragility of the carrier matrix [4]. In vivo studies have shown that approximately 39.9% of rhBMP-2 remains at the implantation site one day after administration, decreasing to 0.5% within three weeks, indicating rapid diffusion and clearance [5]. Released rhBMP-2 can further distribute beyond the target site, potentially contributing to ectopic bone formation or local inflammation. Proteolytic degradation and systemic elimination lead to a short biological half-life, while the initial burst phase results in transiently high local concentrations that may cause adverse tissue reactions [4]. Bone regeneration proceeds through the following overlapping phases: an early inflammatory phase (first the few days post-injury), a reparative phase (weeks of new tissue formation), followed by a remodeling phase [6]. Relative to smaller mammalian species, such as rodents, rabbits, and sheep, which exhibit faster bone healing and remodeling rates [7], human bone repair is characterized by a delayed release of endogenous BMP-2, with a peak expression 7–14 days post-fracture [8,9]. This availability of growth factors in specific phases of tissue repair is tightly regulated and naturally modulated by the extracellular matrix (ECM) and its inhibitors. Acting as a reservoir, the ECM protects and controls the spatio-temporal activity of growth factors by releasing them in response to matrix degradation [10,11]. The initial inflammatory phase is crucial for triggering tissue healing, but an excessive or prolonged inflammatory response can be detrimental [6,12]. When rhBMP-2 is surface-attached to an absorbable collagen sponge carrier, it results in a burst and uncontrolled release coinciding with the inflammatory phase of bone healing [5]. This supraphysiologic rhBMP-2 bioavailability, immediately post-implantation, interferes with the inflammatory phase of bone healing, and is associated with adverse inflammation and neurologic complications that impair bone regeneration [13,14,15,16,17]. In preclinical studies, an initial burst of rhBMP-2 has been shown to trigger the recruitment of large numbers of macrophages and provoke an exaggerated inflammatory reaction (often manifesting as granuloma, seroma, or hematoma formation) around the implant [18]. Clinically, such early inflammation can translate to complications like painful swelling, neurological deficits, or even airway compression in cervical [19,20].

It has been shown that delaying the delivery of rhBMP-2, such that less is presented during the inflammatory phase and more in the repair phase [18], or until the bone healing phase, leads to improved outcomes [18,21,22]. This delayed peak corresponds to the natural spatio-temporal release pattern of endogenous BMP-2 in human fracture healing [2].

Whilst various carriers for rhBMP-2 surface attachment have attempted to overcome retention challenges, the collective evidence indicates a fundamental limitation of surface rhBMP-2, which is its inherent immediate bioavailability and subsequent receptor activation [23,24,25]. The mechanistic constraint of surface-bound rhBMP-2 arises from its presentation mode, whereby the entire protein fraction is immediately exposed to cell surface receptors, inducing rapid activation and signal attenuation. In contrast, matrix-bound BMP-2 alters the spatio-temporal presentation of the ligand, sustaining receptor engagement over time and promoting prolonged SMAD phosphorylation and signaling [24]. Thus, surface-attached delivery strategies fail to address the sequential needs of bone healing.

Various carrier materials were designed to effectively delivery rhBMP-2, including polymeric microspheres, hydrogels, and nanoclay-based composites [26,27,28]. Hydrogel-based drug delivery methods have emerged as potential solutions for bone regeneration due to their biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and ability to support cell growth and differentiation [19,20]. However, hydrogels have several limitations for bone therapies, such as their poor mechanical strength for load-bearing applications, high swelling ratio, rapid degradation, potential immune responses, and leakage due to needle injections [20,29,30]. Similarly, nanoclay–composite hydrogels emerged recently as promising carriers, due to their binding affinity for biomolecules, dose-controlled release strategy, and osteogenic potential [27,31]. Despite promising results, their clinical translation remains limited by challenges with cytotoxicity, biodistribution, mechanical stability, immune reactions, and uniform manufacturing [31,32]. Conventional polymer-based encapsulation systems, such as Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres, or films produced via solvent-based double-emulsion or microfluidic techniques, have improved sustained release but often suffer from solvent-induced protein instability, high burst release, and poor scalability for manufacturing [33]. These limitations have motivated the development of solvent-free thermally controlled systems that ensure greater formulation stability and clinical translatability. Calcium phosphate ceramics remain the gold standard material in bone regeneration, owing to their excellent biocompatibility and osteoconductive properties [34]. In particular, β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) supports bone remodeling through osteoclast-mediated resorption that proceeds in parallel with new bone ingrowth, ultimately resulting in the complete replacement by native bone [35,36]. Moreover, β-TCP is a clinically approved and widely used material for bone-grafting applications [36]. Combining β-TCP with Poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PDLLGA) provides a novel strategy to unite the osteoinductive BMP-2 with the osteoconductive properties of the ceramic, using a controlled release profile provided by the polymer [37,38]. Among polymer-based carriers, PDLLGA was chosen over Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) due to its amorphous structure, which enables uniform degradation within weeks to a month, a timeframe that aligns with the sequential needs of bone regeneration and its controlled release system [38]. Moreover, its faster resorption rate, reduced acidic accumulation, and improved protein stability make it an ideal carrier for temporary BMP-2 delivery compared with the more crystalline and slowly degrading PLLA [39].

An ideal delivery would mimic the natural BMP-2 patterns during fracture healing, shield the majority of the implanted rhBMP-2 from initial receptor binding, and provide a controlled long-term release coinciding with the repair phase. The encapsulation of rhBMP-2 in biodegradable carriers has been explored as a potential strategy to achieve these goals [40,41]. The initial bioavailability can be tempered by providing “dose shielding” of the protein from the local tissue. This encapsulation strategy has been shown to reduce the inflammatory response relative to collagen sponge delivery [40]. To date, no clinically available rhBMP-2 product employs an encapsulated delivery strategy that offers a safer and more controlled alternative for bone regeneration. PDLLGA (50:50) is a biocompatible polymer used in various drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and cleared for medical device products. It is known for its modifiable biodegradation profile [42], making it well-suited as a biomaterial to match the various phases of bone repair. Encapsulating rhBMP-2 in PDLLGA pellets should provide “dose shielding” of the growth factor during the acute inflammatory phase, but the molecular consequences of incorporating and processing the rhBMP-2 within a clinical-grade polymer matrix is unclear.

In the present preclinical study, we develop clinical-grade rhBMP-2-loaded PDLLGA (50:50) pellets as a potential encapsulated delivery system and assess the quality of the released protein even after long-term shelf storage, to evaluate its bioactivity and therapeutic relevance. The protein quality of the released rhBMP-2 was assessed by determining the size, charge, and purity, using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and capillary electrophoresis (CE). The binding kinetics of the released rhBMP-2 to the BMP receptor type IA (BMPR-IA) were analyzed using bio-layer interferometry (BLI). Finally, we analyzed the osteogenic potential of the clinical-grade product (LDGraft) that compromises PDLLGA encapsulation of rhBMP-2 combined with β-TCP granules within a poloxamer 407 carrier.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. rhBMP-2 Encapsulation and Feedstock Preparation

Pellets containing rhBMP-2 were manufactured using a 9 mm twin screw extruder fitted with a bespoke hollow die, conveyor, and granulator (Three-Tec, Seon, Switzerland). A feedstock was prepared by first lyophilizing (SP VirTis AdVantage Pro Freeze Dryer, SP Scientific, Warminster, PA, USA) a solution of Escherichia coli (E. coli), derived rhBMP-2 (Locate Bio, Nottingham, UK) and hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (cyclodextrin, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 1% acetic acid. The resulting lyocake was disrupted, sieved, and geometrically mixed with milled PDLLGA (50:50) (Evonik, Essen, Germany) and poloxamer 407 (P407, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) to prepare the final feedstock which was delivered to the hot-melt extruder (as described elsewhere in WO2022238718A1). The residence time during extrusion was approximately 6–8 min, with processing temperatures ranging from 60 to 80 °C; quantitative data on shear stress were not available. The hollow extrudate was pelletized to form short tubes of less than 1.3 mm by the longest dimension. To minimize the risk of rhBMP-2 inactivation during hot-melt extrusion, hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin was included as a stabilizing excipient to shield the protein from thermal and shear stress. Additional conditioning and packaging steps were applied before and during irradiation to maintain protein integrity. The rhBMP-2 pellets were subsequently irradiated using 25–32.5 kGy X-ray irradiation (Steris, Biel, Switzerland). X-ray irradiation was employed for terminal sterilization, as it provides a shorter exposure time and a lower product temperature than gamma irradiation, thereby reducing the risk of thermal and radiolytic damage to rhBMP-2. The method also enables greater process scalability and dose uniformity compared with E-beam irradiation. As a control material, empty pellets (EP) were manufactured as above, without the inclusion of rhBMP-2. The SDS-PAGE and BLI assays utilized rhBMP-2 pellets alone, and the ALP assay combined the rhBMP-2 pellets with β-TCP, poloxamer 407, and saline to form a putty (LDGraft), as described in patent WO2022238718A1. After manufacturing, pellets/LDGraft were frozen at −20 °C, and subsequent usage was considered as time zero (T0). For shelf-life evaluation, separate batches of pellets were stored at room temperature (RT) (25 ± 2 °C, 60% relative humidity (RH)) for defined periods prior to testing to assess long-term stability and protein release (Tn with n = the number of dates stored at RT).

2.2. Molecular Weight Determination of Released rhBMP-2 from Pellets by SDS-PAGE

Pellets (T0) were thawed and rhBMP-2 (0.5 µg/well) was released from pellets utilizing previously described methodology [43]. Extracted samples were added to Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were boiled at 95 °C for 5 min using a dry bath system (Starlab International; Hamburg, Germany) before loading. SDS-PAGE was performed by loading 0.5 µg of rhBMP-2 per lane under non-reducing conditions and run alongside a pre-stained ladder (PageRuler™ Plus, 10 to 250 kDa, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using Novex™ Tris-Glycine Gels (10–20%, WedgeWell™ format; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Gel electrophoresis was performed using a mini gel tank (Invitrogen) powered by Fisherbrand Mini 300V Plus, (Thermo Fisher Scientific), at 125 V for 40 min and then 50 V for 20 min. PierceTM Silver Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as per manufacturer instructions for the staining of the gels. Analysis of the gels was performed manually after taking images using FastGene B/G GelPic Box (GeneFlow, Lichfield, UK).

2.3. Receptor Binding Analysis of rhBMP-2 to rhBMPR-IA/ALK-3 by BLI

rhBMP-2 formulated within PDLLGA pellets and EP as reference, were thawed (T0) and protein released into the release buffer (1× Kinetics Buffer (KB); 1× Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), 0.01% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), 0.002% Tween20, pH 7.4) through a controlled incubation process. Specifically, 60 ± 0.5 mg of pellets were incubated in 1 mL of 1× KB at 37 ± 2 °C for 24 ± 2 h with agitation at 350 revolutions per minute (rpm). Following incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 146× g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was then gently mixed by inversion (20 times), aliquoted, and stored at −75 ± 15 °C for subsequent analysis. The exact concentration of rhBMP-2 in the release buffer was not determined; however, all samples were treated and diluted equally prior to sensor loading, enabling relative comparison of binding affinities. On the day of the binding assay, the supernatant was buffer exchanged using spin desalting columns (Zeba™ Spin Desalting Columns, 7K MWCO, Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The binding interaction between the released rhBMP-2 and rhBMPR-IA/Activin Receptor-like Kinase 3 (ALK-3) (Fc Chimera Protein, CF, Catalog #: 2406-BR, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was evaluated using BLI on an OctetRED96 system (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) with nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) biosensors (Sartorius). The rhBMP-2 lacks a histidine tag; however, it was successfully immobilized on Ni–NTA biosensors, likely via native histidine or metal-coordinating amino acids. To ensure that the subsequent binding of BMPR-IA was specific and not due to non-specific protein adsorption or background interference, control experiments were performed (Appendix A). To verify non-specific surface loading and selective interaction with BMPR-IA, the following BLI studies were assessed: (i) validation of rhBMP-2 immobilization and structural integrity of released rhBMP-2 (Scheme A1) and (ii) selective interaction or rhBMP-2 with BMPR-IA (Scheme A2). The study included the following four control conditions: (1) EP (PDLLGA pellets without rhBMP-2); (2) force-degraded rhBMP-2 released from PDLLGA pellets; (3) native released rhBMP-2 from PDLLGA pellets (untreated); and (4) standard rhBMP-2 (drug substance, non-encapsulated).

All samples were equally diluted and loaded under identical conditions, and BLI signal during loading was used to assess binding to the Ni–NTA surface. The primary BLI experiment was designed to evaluate the ability of encapsulated rhBMP-2 subsequently released from pellets, to bind BMPR-IA under physiological conditions. Ni–NTA biosensors were loaded with BMP-2-containing release material and subsequently exposed to BMPR-IA to assess binding kinetics and interaction specificity.

Force-degraded rhBMP-2 was used as negative control protein. Degradation was achieved by incubating the pellets at 60 °C for 7 d, and the protein was subsequently released following the procedure described above. As a positive control, rhBMP-2 (the drug substance, non-encapsulated) was immobilized on Ni–NTA biosensors and exposed to BMPR-IA to confirm specific receptor binding. A no-load control (sensor without immobilized rhBMP-2) was included to verify the absence of non-specific surface binding.

For the primary binding assay, biosensors were prewetted in 1× KB for 10 min. A baseline was established in 1× KB, followed by a second baseline using released material from EP. Biosensors were loaded with rhBMP-2-containing released material from PDLLGA pellets for 120 s, equilibrated in 1× KB, and exposed to five non-zero concentrations of BMPR-IA (625, 312.5, 156.3, 78.1, and 39.1 nM), along with a buffer-only control, to assess the binding association. Dissociation was monitored by transferring the biosensors back into 1× KB. To account for assay drift, sensorgrams were reference-subtracted using data from the buffer-only control, and binding curves were aligned at 5 s post-baseline before global fitting to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using Octet Data Analysis software (Version: 9.0.0.14, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), to obtain kinetic constants kon, koff and KD (KD = koff/kon). The assay’s repeatability was assessed by a single analyst under same experimental conditions, while intermediate precision was evaluated through replicate experiments performed by two independent analysts on different days.

2.4. Molecular Stability Assessment Using Capillary Electrophoresis

CE was performed to analyze the molecular stability of released rhBMP-2 from pellets. PDLLGA pellets containing rhBMP-2 were stored at −20 °C to arrest aging and subsequently provide a day 0 sample (T0), or at 25 ± 2 °C, 60% RH for 129, 227, 551, and 732 d before testing (T129, T227, T551, and T732). Duplicate rhBMP-2 samples (30 ± 0.5 mg each) were extracted with 8 mL of pre-chilled 100% acetone, vortexed, and incubated at −20 °C for 1 h. Following centrifugation at 7142× g for 10 min, 6 mL of the supernatant was discarded. The remaining pellet and residual acetone were transferred to fresh tubes. To maximize protein recovery, the original tubes were rinsed with 2 mL of pre-chilled acetone, vortexed, and transferred to new tubes. After a second centrifugation (7142× g, 10 min), supernatants were removed, and pellets were air-dried. Pellets were resuspended in 100 µL of SDS sample buffer. For alkylation, 1 µL of 20% SDS and 10 µL of 0.5 mol/L iodoacetamide were added and incubated at RT for 10 min. Samples were then denatured under reducing conditions using β-mercaptoethanol and SDS, followed by incubation at 70 °C for 10 min. After cooling, the samples were measured by CE-SDS analysis and a molecular weight sizing standard (Sciex, SDS-MW Analysis Kit, Cat No. 39095, Framingham, MA, USA), a 10 kDa blank, and a reference standard of the non-encapsulated rhBMP-2 (3 mg/mL) were included to evaluate the changes over time by monitoring molecular weight profiles through a sieving mechanism.

CE-SDS was performed on a PA 800 Plus system (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) equipped with Empower 3 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Separations were carried out using bare fused silica capillaries (30.2 cm total, 20 cm effective length) under reducing conditions with β-mercaptoethanol and SDS. Samples were incubated at 70 °C prior to injection. Protein migration was detected by UV absorbance at 220 nm. Injection sequences and instrument settings followed validated standard operating procedures. Data analysis was performed using Empower 3 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA, version 3.3). with integrated molecular weight calibration. Purity was assessed as the percentage of main peak (rhBMP-2 homodimer), low molecular weight species (LMWS), and high molecular weight species (HMWS).

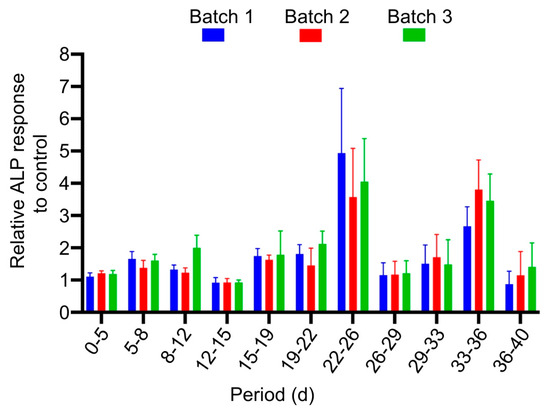

2.5. Cell-Based ALP Assay to Assess the Osteogenic Potential of Released rhBMP-2

To assess the osteoinductive potential of released rhBMP-2 from the clinical graft product, LDGraft, Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was quantified in C2C12 cells. LDGraft (1× 5cc pack) was stored at −20 °C until thawed, for use in the assay (T0). C2C12 cells were cultured in medium (DMEM, low glucose, GlutaMAX™ Supplement, Pyruvate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 10% heat-inactivated Fetal Calf Serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptavidin (Sigma Aldrich), at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. A total of 40,000 cells in a volume of 1 mL/well was plated into a 12-well plate for 24 h. LDGraft (mean sample weight 0.1453 g) was exposed to cells in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane inserts (Avidity Science, Waterford, WI, USA, formerly Triple Red), covered with 2 mL of fresh medium at the basolateral chamber and 1ml to the insert. The relative positions of each sample in the 12-well plate were maintained throughout the 28-day study. Liquid rhBMP-2 (0.2 μg/mL) was used as a positive control, while culture medium served as the negative control. After 72 h or 96 h incubation, the inserts were transferred onto freshly plated cells (prepared the previous day), along with fresh medium and controls. Harvested cells were lysed (CelLytic M, Sigma Aldrich), the ALP levels measured (SIGMAFAST p-Nitrophenyl phosphate tablets, Sigma Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and results were normalized to protein content of the cell lysate as measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay, (BCA Protein Assay Kit, Pierce, Appleton, WI, USA).

The PET membrane insert transfer/ALP assay cycle was repeated up to 40 d after exposure. Relative ALP activity was normalized to the response of the time-matched positive control of known rhBMP-2 input. This approach ensured valid comparisons across all experiments with varying incubation duration. ALP activity was measured for three independent manufacturing batches (n = 3), with each sample tested in triplicate (technical replicates). Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Structural Analysis of Released rhBMP-2 by SDS-PAGE

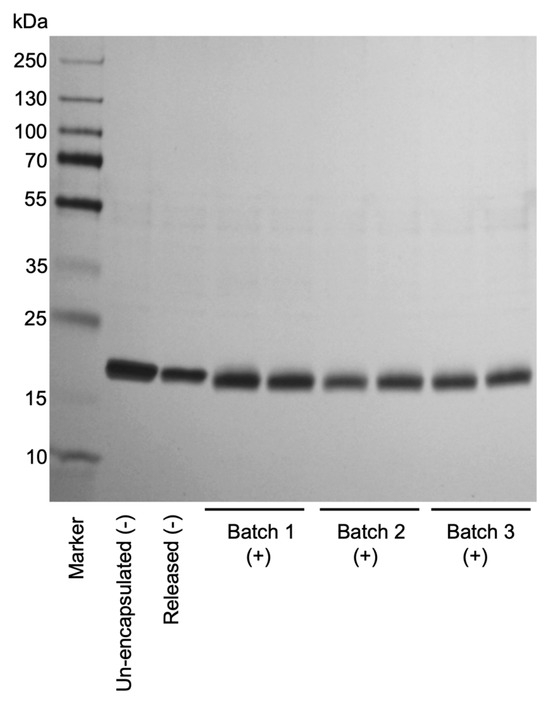

The protein structure of released rhBMP-2 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions to assess potential structural alterations. Figure 1 shows SDS-PAGE analysis of rhBMP-2 extracted from three different batches following irradiation, compared to non-irradiated released protein and native rhBMP-2. All samples showed a predominant band within the 15–25 kDa range, corresponding to the expected dimeric form of rhBMP-2, with no evidence of high molecular weight aggregates. Under non-reducing conditions, rhBMP-2 migrated at approximately 15–25 kDa on SDS-PAGE, consistent with the known anomalous migration of cystine-linked dimers (theoretical MW ≈ 26 kDa) caused by their compact, disulfide-stabilized structure comprising seven intrachain and one interchain disulfide bond [44,45]. These results demonstrate that the native disulfide-linked structure of rhBMP-2 remained intact throughout encapsulation, terminal sterilization, and the subsequent release from the pellets.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of rhBMP-2 samples released from irradiated and non-irradiated pellets, visualized by silver staining. Pellet-released rhBMP-2 from three independent irradiated batches (1–3, +) was compared with released rhBMP-2 from non-irradiated (-) samples, as well as with un-encapsulated, and non-irradiated (-) control samples (T0). All samples were run under non-reducing conditions to assess protein integrity and degradation. A molecular weight marker (Marker) was included for reference. The gel shows consistent bands between 15 and 25 kDa for all irradiated batches comparable to both non-irradiated released and un-encapsulated control samples.

3.2. Molecular Stability Assessment of Released rhBMP-2 by Capillary Electrophoresis

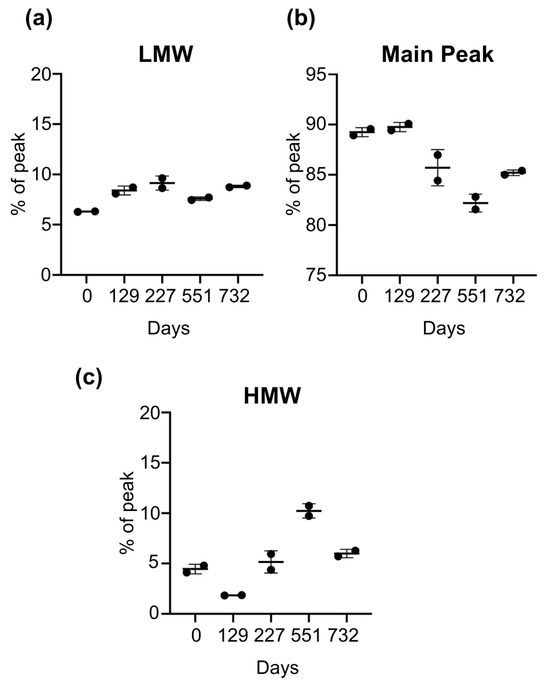

To assess the structural integrity and molecular weight species distribution of released rhBMP-2 from PDLLGA after defined long-term storage intervals, CE-SDS, under denaturing conditions, was employed. This technique enables the precise separation of protein species according to their molecular size. Samples from multiple time points (duplicates) were analyzed to monitor fragmentation, aggregation, or degradation over time. T0 served as the reference, reflecting the initial release sample with initial protein integrity prior to storage-induced changes. The main peak corresponding to intact rhBMP-2 homodimer accounted for 89.240% of the total signal, while LMW and HMW species were present at 6.300% and 4.450%, respectively (Table 1). The results provide insight into the purity, stability, and consistency of RT-stored rhBMP-2 in PDLLGA pellets across defined endpoints (T129, T227, T551, T732 days). Throughout the storage period, slight variations were observed in the main peak as well as in the LMW and HMW species. However, no consistent trend indicating accumulation of either the HMW or LMW species was detected across time points, supporting the overall stability of the protein. The lowest dimer content (82.2%) was detected at T551, which corresponds to the peak in HMW species (10.23%). Both main peak and HMW species returned to their T227 levels at the final storage endpoint, T732. These fluctuations may represent background assay variability, or a slight increase in pH for the sample at T551, which is known to increase rhBMP-2 aggregation [44]. Despite minor shifts, rhBMP-2 remained structurally stable until the study endpoint, T732, with the main peak consistently dominant. The relative distribution of the LMW, main peak, and HMW species across time points is shown in Figure 2, with quantitative values in Table 1.

Table 1.

CE-SDS analysis of released rhBMP-2 from pellets following long-term storage. Relative peak areas (%) of LMW, main peak, and HMW measured for two samples (n = 2) at each time point (T0, T129, T227, T551 and T732) during the long-term stability study of rhBMP-2 containing PDLLGA pellets. Values expressed as mean (%) and standard deviation (SD). Data shown correspond to those visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Long-term stability of released rhBMP-2 from pellets by CE-SDS analysis. PDLLGA pellets containing rhBMP-2 were stored long-term at conditions simulating RT. Protein stability was assessed of released rhBMP_2 from pellets, using CE-SDS. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation of two independently measured samples per time point (n = 2). Data are shown as relative peak area (%) for multiple time points (days). (a) LMW, (b) the main peak (rhBMP-2 homodimer), and (c) HMW were normalized to represent 100% per sample (days T0, T129, T227, T551, and T732). T0 serves as the reference, representing the as-manufactured release sample with the initial protein integrity, prior to exposure to storage conditions at RT. CE-SDS was performed under reducing and denaturing conditions. Over time, the main peak remained consistently dominant (range 82.2–89.8%), indicating the structural integrity and long-term stability of the encapsulated and subsequently released rhBMP-2 throughout the test period.

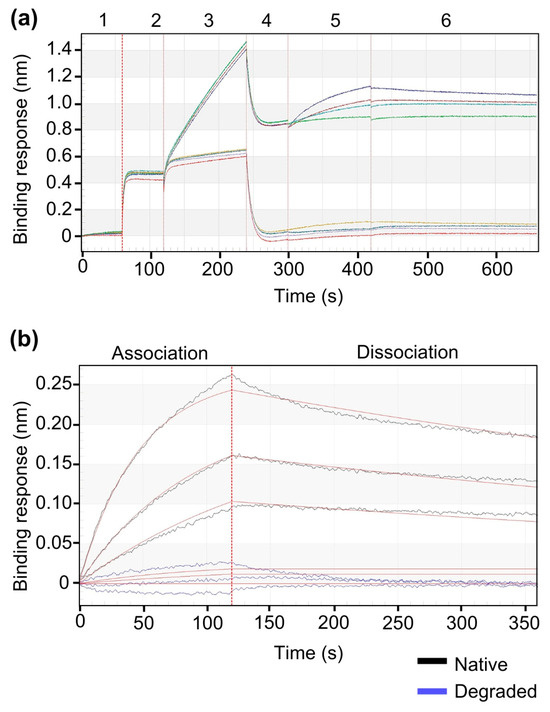

3.3. Binding Affinity of Released rhBMP-2 to BMPR-IA Measured by Bio-Layer Interferometry

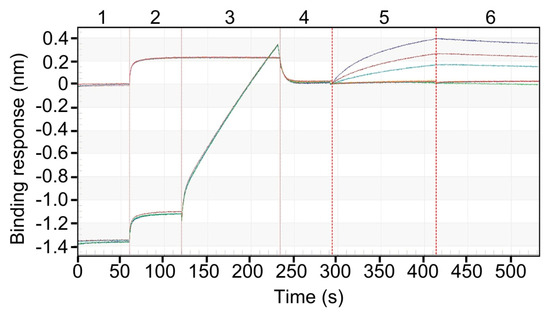

Previously, studies using live cell membranes and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), have shown that BMP-2-induced heteromeric receptor complexes form and disassemble quickly, implying the ligand frequently unbinds and rebinds in a “vibration-like” interaction pattern [46]. Binding affinity to BMPR-IA by rhBMP-2 released from encapsulated PDLLGA pellets was assessed by BLI. Sensorgrams revealed a characteristic binding profile, with robust association and dissociation kinetics observed across defined BMPR-IA concentrations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Specific Binding of rhBMPR-IA to released rhBMP-2 immobilized on the Ni–NTA biosensors. The numbers at the top of the sensorgram (1 to 6) indicate the sequential steps used to measure binding of released rhBMP-2-containing medium (ligand) to rhBMPR-IA (analyte). Released protein from pellets at T0 (60 ± 0.5 mg) was collected and subsequently used for binding studies. The sensogram illustrates a six-step binding sequence. Step 1: 1× KB, pH 7.4. Step 2: Medium from EP. Step 3: Ni-NTA biosensors loading with release buffer from EP (controls, showing flat sensorgram) or released rhBMP-2-containing medium (steep sensorgram). Step 4: Re-establish sensorgram baseline in 1× KB, pH 7.4. Step 5: Association with BMPR-IA (625, 312.5, and 156.3 nM). Step 6: Dissociation in 1× KB, pH 7.4.

Corresponding kinetic analysis revealed a high-affinity interaction for released rhBMP-2, with a dissociation constant (KD) in the low nanomolar range, consistent with previously reported values for native BMP-2 [47]. The observed kinetic parameters were highly reproducible across experiments performed on separate days by different analysts. Intermediate precision analysis yielded an average KD of 4.89 × 10−8 M and a coefficient of variation (CV) of 24%, reflecting acceptable reproducibility across independently performed assays (Table 2), with low inter-run variability in association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants. The inter-assay variability was moderate (CV 24.1%), yet all KD values remained within the expected nanomolar range, indicating consistent receptor-binding affinity across replicates. Control experiments confirmed the specificity of the BLI assay and surface-bound interaction. No binding of BMPR-IA was observed to unloaded Ni-NTA sensors, degraded rhBMP-2, or buffer from EP. Receptor interaction occurred exclusively in the presence of structurally intact, surface-immobilized rhBMP-2, confirming the specificity of both protein and surface-mediated binding (Scheme A1 and Scheme A2).

Table 2.

Intermediate precision of binding method to assess binding affinity of BMPR-IA to released rhBMP-2 immobilized on the Ni-NTA biosensors. Data represent repeated measurements across independent runs (1–4) and analysts (A and B) to assess assay reproducibility and robustness. Kinetic analysis was performed using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model to determine the association and dissociation rates.

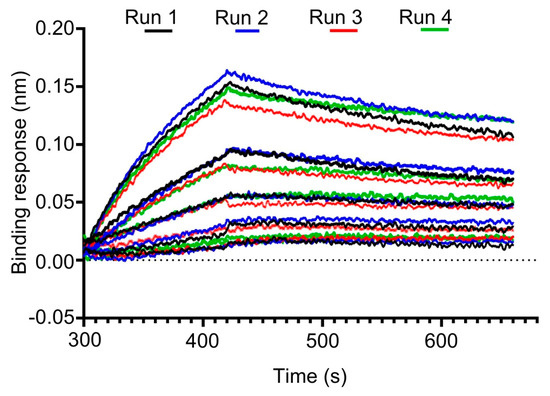

The repeatability of the binding method by a single analyst confirmed the consistency of the assay, with a KD of 5.13 × 10−8 M and CV of 13% across two independent runs indicating minimal analytical drift or artifact (Figure 4 and Table 3).

Figure 4.

Reproducibility of BMPR-IA binding to pellet-released rhBMP-2 on Ni-NTA biosensors. Sensorgrams illustrate the intermediate precision of the binding assay. Data reflect repeated measurements across independent runs (1–4) and different analysts, demonstrating the assay’s reproducibility and robustness.

Table 3.

Repeatability of binding method to assess binding affinity of BMPR-IA to released rhBMP-2 immobilized on the Ni-NTA biosensors. Results show intra-assay variability across technical replicates, demonstrating assay consistency.

3.4. ALP Activity Induced by Released rhBMP-2 in Cell-Based Assay

ALP response was measured to evaluate the osteogenic potential of the released rhBMP-2 over a period of 40 days. The release of bioactive rhBMP-2 was determined by assaying the ALP activity in whole cell lysates of C2C12 cells exposed to LDGraft. A strong ALP response was observed at each time point throughout the assay period, indicating the bioactive potential of rhBMP-2 post-encapsulation (Figure 5). ALP response was highest at days 22–26 and 33–36, compared to the remaining time points. All values were normalized to the corresponding positive control to allow consistent comparison across experiments. Minimal ALP activity was detected in negative controls, confirming that the observed effect was specific to the presence of released rhBMP-2.

Figure 5.

Relative ALP response of released rhBMP-2 from LDGraft. C2C12 cells were exposed to LDGraft (T0) for eleven separate time intervals over a period of 40 days. After each interval, the residual LDGraft was transferred to a new culture of cells and with fresh medium to serve as the next time point. The ALP response was determined at each time point. Values were normalized to a corresponding time-matched positive control (0.2 µg/mL rhBMP-2 drug substance. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent manufacturing batches (n = 3), each tested in triplicates. Normalization enables direct comparison of osteogenic activity, across different time points during long-term rhBMP-2 release, and independent manufacturing lots, thereby demonstrating batch-to-batch consistency. All LDGraft batches induced a statistically significant increase in ALP activity compared with control cells at all time points (p < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

4. Discussion

The current study demonstrates that encapsulating rhBMP-2 in PDLLGA (50:50) pellets via hot-melt extrusion and irradiation effectively preserves the molecular integrity and biological activity of the protein. Specifically, we demonstrated that the protein structure remained intact post-encapsulation, as shown by SDS-PAGE and CE-SDS analyses (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The accumulation of protein agglomerates, in addition to the expected structure of the protein, may been seen when they are processed, and care must be taken to avoid this [42,48,49]. The comparison with the non-released, non-irradiated reference protein confirmed that the encapsulation, sterilization, and release process did not markedly compromise the structural integrity of rhBMP-2, as evidenced by the preserved band pattern in SDS-PAGE. Analysis showed no evidence of high molecular weight aggregates or degradation products on SDS-PAGE, and all three batches displayed a predominant band corresponding to the expected dimeric form of rhBMP-2 (Figure 1). Although the theoretical molecular weight of the rhBMP-2 dimer is ~26 kDA, its migration at 15–25 kDA under non-reducing conditions is well documented and reflects the anomalous behavior of compact, disulfide-linked dimers rather than discrepancy in molecular mass [44,45]. Furthermore, CE-SDS analysis provided insights into the molecular stability of the released rhBMP-2 under long-term storage conditions. Throughout the storage period, CE-SDS analysis revealed only minor changes in the distribution of the LMW and HMW species. The proportion of the HMW species increased slightly, from 4.450% at T0 to 10.230% at T551, while the LMW species showed a moderate rise, from 6.300% at T0 to 8.805% at T732. These small variations (2.5 percentage points for the LMW, and 5.78 percentage points for the HMW) are within the expected analytical variability and indicate acceptable levels of aggregation and degradation over time. Overall, the consistent main peak (89.240% at T0 to 85.200% at T732) and stable electrophoretic profile across all time points demonstrate that the encapsulated rhBMP-2 retained its structural integrity and exhibited no evidence of progressive degradation during long-term storage (Figure 2 and Table 1). Additionally, the encapsulation polymer (PDLLGA) demonstrated high stability, without any marked changes in molecular weight or polydispersity until 732 days of storage, measured by Gel Permeation Chromatography (See Appendix A, Table A1). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the encapsulation and sterilization process preserved rhBMP-2 integrity, despite prior reports that proteins are susceptible to thermal or mechanical stresses [49,50,51,52,53], and to terminal sterilization [54,55,56], which can induce misfolding or aggregation, and ultimately compromise therapeutic efficacy.

Critically, the released rhBMP-2 retained its molecular function, as demonstrated by its receptor-binding affinity to BMPR-IA, following both processing and terminal sterilization, as confirmed through rigorous kinetic characterization using BLI. The receptor-binding assay focused on BMPR-IA (type I receptor), which mediates the initial high-affinity interaction with BMP-2, followed by the recruitment of the lower-affinity type II receptor (BMPR-II). BMPR-IA thus provides a sensitive and well-established model for assessing ligand integrity and receptor-binding competence, while BMPR-II’s transient interaction makes it less suitable for kinetic BLI analysis [57,58]. Bioactivity, defined here as functional receptor engagement with BMPR-IA, was confirmed using BLI, with KD in the low nanomolar range (average KD ~4.9 × 10−8 M) (Figure 3). This is comparable to the low single-digit KD values reported in the literature [47,59,60], suggesting minimal loss of binding competence through encapsulation and terminal sterilization. Although the inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was moderate (24.1%), this level of variability is acceptable for surface-based ligand–receptor binding assays, such as BLI, where small differences in receptor immobilization density, ligand orientation, and mass transport can affect apparent kinetics. Importantly, all KD values remained within the expected nanomolar range, demonstrating that the observed variation reflects methodological sensitivity rather than reduced protein stability. Overall, the BLI assay demonstrated consistent performance, confirming that the bioactivity of rhBMP-2 post-encapsulation is both reproducible and intrinsic to the released protein.

The preserved receptor-binding profile further supports that the tertiary structure required for effective BMPR engagement was maintained. In vitro, upon the binding of BMP-2 to BMPR type I, BMP-2 subsequently recruits type II receptors with lower affinity. The overall binding kinetics critically influence the strength and duration of downstream signaling events, including ALP induction [47,57,58]. To test this hypothesis, we have performed cell-based studies with released rhBMP-2 from our clinical-grade product, LDGraft. Results showed a strong ALP response for released rhBMP-2 at all time points (period of 40 d) confirming its osteogenic potential after encapsulation, and long-term storage and release (Figure 5). Since ALP induction requires active downstream signaling, BMP-2 must bind both type I (e.g., BMPR-IA) and type II (e.g., BMPR-II) receptors [46]. This implies that released rhBMP-2 from LDGraft is fully bioactive and facilitates the formation of a heteromeric receptor complex essential for downstream osteogenic signaling. The elevations in ALP response at days 22–26 and 33–36 may indicate a transient increase in rhBMP-2 release rate in vitro, potentially associated with the degradation and surface erosion phases of the LDGraft composite matrix (β-TCP/PDLLGA), or influenced by serum proteins and residual enzymatic activity. However, this remains a hypothesis that would require further investigation to confirm. Although this study does not seek to establish a detailed release profile, it focuses on demonstrating that the released rhBMP-2 retains its osteogenic potential, as evidence by sustained ALP activity in vitro. As previously shown, β-TCP-based ceramics primarily act as osteoconductive scaffolds and do not independently initiate osteogenic differentiation in C2C12 cells. Therefore, the observed ALP activity confirms the bioactivity of released rhBMP-2 rather than the effect of the LDGraft itself [61].

Our findings provide valuable insights into enhancing the therapeutic delivery of rhBMP-2 in bone regeneration. Numerous reports have highlighted the drawbacks of the burst-release kinetics associated with surface-attached delivery materials, which result in supraphysiologic local concentrations of BMP-2 in the immediate post-implantation period [62]. The leakage and uncontrolled delivery of rhBMP-2 have been linked to pronounced inflammatory responses, ectopic ossification, and neurological complications, particularly in the cervical spine [63,64,65].

Our encapsulation approach within PDLLGA offers a potential strategy to decouple rhBMP-2 bioavailability from the inflammatory phase, promoting a more sustained release aligned with the reparative phase of bone healing—a temporal window where endogenous BMP-2 signaling naturally peaks.

This study also extends prior work on polymeric encapsulation systems for rhBMP-2. Our approach uses PDLLGA (50:50), a biodegradable polymer with a well-characterized safety profile, and incorporates formulation modifications such as cyclodextrin and poloxamer 407, which likely act as protein stabilizers during lyophilization, extrusion, and terminal sterilization. The terminal sterilization via X-ray irradiation, as opposed to ethylene oxide or gamma irradiation, appear not to compromise protein integrity. A key strength of this study is the integration of both structural and functional assays, which collectively support the long-term molecular stability and bioactivity of encapsulated rhBMP-2 under long-term storage conditions. This is a critical parameter when considering the translation into therapeutic products, where stability during long-term storage must be ensured without compromising efficacy and safety. The results of this study highlight the strong clinical translation potential of the LDGraft compared to surface-attached delivery systems, such as the collagen sponge carrier. While collagen sponges typically exhibit rapid, uncontrolled burst release, the encapsulation strategy presented here enables a more controlled and sustained release of rhBMP-2, potentially reducing the effective dose required and critically minimizing adverse events. These features make the delivery platform particularly attractive for clinical translation, as they address the key safety and efficiency challenges with currently approved rhBMP-2 delivery platforms. Nonetheless, this study has limitations. The in vitro nature of the receptor-binding assays, while informative, cannot fully predict the in vivo osteoinductive potential. While the molecular integrity, receptor-mediated activity, and downstream osteogenic potential of released rhBMP-2 were assessed under accelerated conditions, the relationship between their storage duration, release kinetics, and osteogenic potential are yet to be fully established. Quantitative release kinetics were not measured in this study, as the analytical design focused on confirming protein stability and bioactivity under accelerated conditions and long-term storage conditions, rather than establishing a detailed release profile. The absence of direct release data limits the ability to directly correlate release kinetics with biological performance. Future studies will aim to characterize release kinetics both in vitro and in vivo, and establish a clear link between release, activity, dose distribution, and efficacy. While PDLLGA is a well-characterized, biocompatible, and FDA-approved polymer, its degradation produces acidic by-products that modulate the pro-inflammatory response of macrophages [66]; these effects should be further evaluated in future in vivo studies.

The in vitro and analytical assays presented here demonstrate that rhBMP-2 retains its integrity post-encapsulation; however, the in vivo performance needs to be elucidated. Future studies will aim to further validate the translational relevance of these findings in vivo, focusing on the therapeutic efficacy and safety of the release and dose-shielding system in preclinical animal models. In particular, the comparison between burst-release and controlled-release systems will be conducted to evaluate differences in bone regeneration, local inflammation, and systemic exposure. Comprehensive histological, molecular, and biochemical analyses will be undertaken to confirm the biological activity of the released growth factor and assess potential adverse effects such as ectopic bone formation and inflammatory reactions. Ultimately, in vivo studies will determine whether our rhBMP-2 encapsulation and dose-shielding approach translates into enhanced healing outcomes, reduced inflammatory responses, or lower effective doses required for bone regeneration. Further in vivo preclinical and clinical evaluations of the LDGraft have already commenced, marking an important step toward its translation into patient care. Given that some authors are affiliated with the manufacturer of the tested biomaterial, the study design and data interpretation were conducted independently to ensure transparency, scientific rigor, and objectivity.

5. Conclusions

This study established that rhBMP-2 encapsulated in PDLLGA retains its structural integrity and biological activity following sterilization, extended storage, and its subsequent release. The clinical-grade product LDGraft further demonstrates preserved osteogenic potency despite long-term storage, underscoring the translational relevance of this delivery approach. These insights are highly relevant to therapeutic safety and efficacy, demonstrating that the protein remains stable and biologically active under the stringent conditions required for clinical-grade manufacturing. Our encapsulation approach offers a reliable dose-shielding strategy for rhBMP-2 that aligns with temporal sequence of bone regeneration, while mitigating the burst release associated with surface-attached carriers. Future studies will validate its therapeutic efficiency and safety, supporting its clinical application in bone repair and spine fusion therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.M. and J.v.B.; Methodology: C.M., E.T., W.H., D.T.V., S.K., and K.S.; Formal Analysis: J.v.B., S.K., and K.S.; Investigation: C.M., E.T., W.H., D.T.V., S.K., and K.S.; Data Curation: C.M., E.T., W.H., S.O., D.T.V., S.K., and K.S.; Writing—original draft preparation: J.v.B., L.-M.A.Z., C.M., and E.T.; Writing—review and editing: J.v.B., K.S., and L.-M.A.Z.; Visualization: J.v.B., S.K., K.S., and L.-M.A.Z.; Supervision and Project Administration: J.v.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Rajgopal Rudrarapu and Pavan Kumar Kunala from Almac Group for providing the CE-SDS data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare the following potential conflicts of interest: C.M., E.T., S.O., W.H., and J.v.B. are all salaried employees of Locate Bio, the manufacturer of LDGraft. L.-M.A.Z. is a paid consultant to Locate Bio and a stock option holder. D.T.V., S.K., K.S. are employees of Custom Biologics. Custom Biologics was subcontracted by Locate Bio to perform the BLI analysis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALK-3 | Activin receptor-like kinase 3 |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| BLI | Bio-layer Interferometry |

| BMPR-IA | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type I A |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| CE-SDS | Capillary electrophoresis–sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| CV | Coefficient Variation |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EP | Empty Pellets |

| FDA | US Food And Drug Administration |

| FRAP | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching |

| GCP | Gel Permeation Chromatography |

| HMWS | High molecular weight species |

| KB | Kinetics Buffer |

| LMWS | Low molecular weight species |

| Ni–NTA | Nickel–Nitrilotriacetic Acid |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PDLLGA | Poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid). |

| PLLA | Poly(L-lactic acid) |

| rhBMP-2 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| β-TCP | β-Tricalciumphosphate |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

To validate the structural integrity and functionality of released rhBMP-2 from pellets, control experiments were performed using Ni–NTA biosensors. rhBMP-2 released from native and force-degraded pellet samples were assessed for their ability to bind the sensor surface and interact with BMPR-IA. As shown in Appendix A, Scheme A1, only the native released rhBMP-2 from pellets exhibited measurable binding to the Ni–NTA surface compared to the force-degraded released protein, indicating specific immobilization. Subsequent injection of BMPR-IA led to distinct association and dissociation profiles, confirming that the immobilized protein retained receptor-binding capability. In contrast, the force-degraded release protein showed minimal to no response, underscoring both the specificity of the immobilization and the structural integrity of the pellet-released rhBMP-2.

Scheme A1.

BLI analysis of BMPR-IA interaction with intact rhBMP-2 and degraded rhBMP-2 as a negative control. (a) Comparable BLI analysis with forge-degraded rhBMP-2 and native rhBMP-2 released from pellets to test the specificity of immobilization and binding to BMPR-IA (b) Zoom-in view of the association and dissociation phases for BMPR-IA binding affinity to native and force-degraded released rhBMP-2.

rhBMP-2 was released from pellets (60 ± 0.5 mg) under defined conditions. (a) Full sensorgram view showing the complete injection sequence (1–6). Step 1: Sensors were equilibrated with 1 × KB (pH 7.4). Step 2: Release buffer collected from EP (reference) was injected. Step 3: Incubation with: (1) native rhBMP-2 released from pellets (upper trace), or (2) buffer containing force-degraded rhBMP-2 released from pellets (used as a negative control protein) (lower trace). Step 4: Re-establishing the baseline in 1× KB (pH 7.4). Step 5: Association with BMPR-IA at decreasing concentrations (625, 312.5, 156.3 and 0 nM BMPR-IA). Step 6: Dissociation in 1 × KB, pH 7.4. Only the native pellet-released rhBMP-2 produced a measurable signal, indicating specific protein immobilization and receptor interaction, while the negative control sample showed minimal to no binding. (b) Zoom-in view of the association and dissociation phases for BMPR-IA to released native (black line) and degraded rhBMP-2 (blue line). Released native rhBMP-2 demonstrated clear binding to BMPR-IA biosensor surface, as indicated by a distinct association phase followed by dissociation upon equilibration with 1 × KB (pH 7.4). In contrast, the force-degraded protein showed no measurable binding affinity, confirming the loss of structural integrity required for immobilization and receptor interaction.

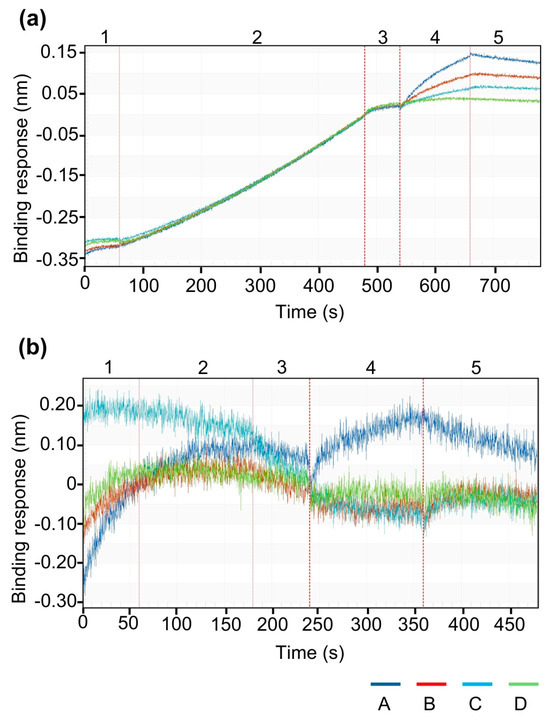

Furthermore, to confirm receptor-specific binding affinity, standard (drug substance, non-encapsulated) rhBMP-2 was loaded onto Ni–NTA biosensors and exposed to BMPR-IA. The resulting signal demonstrated clear association and dissociation profiles, indicating specific receptor interaction. No signal was observed in the absence of protein loading, confirming the specificity of binding and the effectiveness of the immobilization approach (Scheme A2).

Scheme A2.

Validation of BMPR-IA interaction using standard rhBMP-2 as positive control. (a) Immobilization of standard (non-encapsulated, drug substance) rhBMP-2 on Ni–NTA biosensor and binding affinity testing to BMPR-IA.(b) No-load control on biosensors to test BMPR-IA surface binding.

(a) To confirm that released rhBMP-2 immobilized on the Ni–NTA biosensor is biologically active and capable of specific receptor interaction, standard (drug substance, non-encapsulated) rhBMP-2 was loaded onto the sensor and exposed to different BMPR-IA concentrations. A sequential series of injections (1–5) was applied to the sensors. Step 1: Equilibration of sensor in 1 × KB (pH.7.4). Step 2: Load of standard (drug substance, non-encapsulated) 1 µg/mL rhBMP-2. Step 3: Re-establish sensorgram baseline in 1× KB (pH 7.4). Step 4: Association with BMPR-IA (A:50; B: 25; C: 12.5; D: 0 µg/mL). Step 5: Dissociation in 1× KB (pH 7.4). The sensorgram showed a clear association and dissociation profile, demonstrating specific receptor binding. (b) No-load control (Ni–NTA sensor without rhBMP-2) exhibited no baseline shift upon BMPR-IA injection in step 4, confirming the absence of non-specific binding to the sensor surface. This experiment serves as a positive control validating both the immobilization strategy and the specificity of BMP-2–BMPR-IA interaction.

Appendix A.2

The encapsulation polymer was evaluated for long-term stability. The molecular weight and polydispersity of PDLLGA were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) using a Waters Alliance HPLC system with RI detector equipped with Styragel HR-2 column (300 × 7.8mm, 5 µm, Waters) and 2 × Styragel HR-5E column (300 × 7.8mm, 5 µm, Waters). Samples were dissolved in vacuum-filtered HPLC Grade Chloroform, stabilized with Amylene (250 µL of Toluene per 1000 mL of Chloroform), and eluted at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Calibration was performed with polystyrene standards (Agilent EasiCal PS-1). Data are shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Stability analysis of PDLLGA under controlled conditions (25 °C/60% RH). Average molecular weight (NLT 30 kDa) and polydispersity index were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). Data from multiple long-term storage time points confirmed compliance with specifications.

Table A1.

Stability analysis of PDLLGA under controlled conditions (25 °C/60% RH). Average molecular weight (NLT 30 kDa) and polydispersity index were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). Data from multiple long-term storage time points confirmed compliance with specifications.

| Time Point (d) | Molecular Weight (kDA) | Polydispersity |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 47 | 1.579 |

| 129 | 47 | 1.572 |

| 227 | 47 | 1.615 |

| 551 | 47 | 1.517 |

| 732 | 50 | 1.610 |

References

- Urist, M.R. Bone: Formation by Autoinduction. Science 1965, 150, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Benecke, J.P.; Tarsitano, E.; Zimmermann, L.-M.A.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Walsh, W.R.; Bae, H.W. A Narrative Review on Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2: Where Are We Now? Cureus 2024, 16, e67785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeherman, H.J.; Wilson, C.G.; Vanderploeg, E.J.; Brown, C.T.; Morales, P.R.; Fredricks, D.C.; Wozney, J.M. A BMP/Activin A Chimera Induces Posterolateral Spine Fusion in Nonhuman Primates at Lower Concentrations Than BMP-2. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2021, 103, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, W.; Uludag, H.; Foskett, S.; Biron, R.; Sargeant, C. Characterization of Absorbable Collagen Sponges as RhBMP-2 Carriers. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 187, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeherman, H.I.; Jian, V.X.; Mary, L.; Bouxsein, L.; Wozney, J.M. RhBMP-2 Induces Transient Bone Resorption Followed by Bone Formation in a Nonhuman Primate Core-Defect Model. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2010, 92, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, L.; Recknagel, S.; Ignatius, A. Fracture Healing under Healthy and Inflammatory Conditions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, T.; Lopez, M.J. An Overview of de Novo Bone Generation in Animal Models. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Ghazizadeh, M.; Shimizu, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Saito, N.; Yagi, T.; Mashiko, K.; Mashiko, K.; Kawai, M.; Yokota, H. Delayed Expression of Circulating TGF-Β1 and BMP-2 Levels in Human Nonunion Long Bone Fracture Healing. J. Nippon. Med. Sch. 2017, 84, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuman, M.; Haifeng, C.B.W. Detection of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Levels in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Delayed Fracture Healing. Jilin Med. 2007, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.; Correns, A.; Furlan, A.G.; Spanou, C.E.S.; Sengle, G. Controlling BMP Growth Factor Bioavailability: The Extracellular Matrix as Multi Skilled Platform. Cell. Signal. 2021, 85, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correns, A.; Zimmermann, L.M.A.; Baldock, C.; Sengle, G. BMP Antagonists in Tissue Development and Disease. Matrix Biol. Plus 2021, 11, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, M.; Rhee, C.; Utsunomiya, T.; Zhang, N.; Ueno, M.; Yao, Z.; Goodman, S.B. Modulation of the Inflammatory Response and Bone Healing. Front. Endocrinol. Lausanne 2020, 11, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.B.; Taghavi, C.E.; Song, K.J.; Sintuu, C.; Yoo, J.H.; Keorochana, G.; Tzeng, S.T.; Fei, Z.; Liao, J.C.; Wang, J.C. Inflammatory Characteristics of RhBMP-2 in Vitro and in an in Vivo Rodent Model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011, 36, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.B.; Taghavi, C.E.; Murray, S.S.; Song, K.J.; Keorochana, G.; Wang, J.C. BMP Induced Inflammation: A Comparison of RhBMP-7 and RhBMP-2. J. Orthop. Res. 2012, 30, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liau, Z.Q.G.; Lam, R.W.M.; Hu, T.; Wong, H.-K. Dose-Dependent Nerve Inflammatory Response to RhBMP-2 in a Rodent Spinal Nerve Model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017, 42, E933–E938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Daubs, M.D.; Montgomery, S.R.; Aghdasi, B.; Inoue, H.; Tian, H.; Suzuki, A.; Tan, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Ruangchainikom, M.; et al. BMP-2 Adverse Reactions Treated with Human Dose Equivalent Dexamethasone in a Rodent Model of Soft-Tissue Inflammation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Abbah, S.A.; Hu, T.; Toh, S.Y.; Lam, R.W.M.; Goh, J.C.-H.; Wong, H.-K. Minimizing the Severity of RhBMP-2–Induced Inflammation and Heterotopic Ossification with a Polyelectrolyte Carrier Incorporating Heparin on Microbead Templates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013, 38, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.H.; Kim, S.E.; Park, J.Y.; Kundu, J.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, S.S.; Cho, D.W. Three-Dimensional Printing of RhBMP-2-Loaded Scaffolds with Long-Term Delivery for Enhanced Bone Regeneration in a Rabbit Diaphyseal Defect. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2014, 20, 1980–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; He, H.; Li, B.; Hou, T. Hydrogel as a Biomaterial for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Gao, M.; Syed, S.; Zhuang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.Q. Bioactive Hydrogels for Bone Regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeherman, H.; Li, R.; Li, X.J.; Wozney, J. Injectable RhBMP-2/CPM Paste for Closed Fracture and Minimally Invasive Orthopaedic Repairs. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2003, 3, 317–319; discussion 320-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seeherman, H. RhBMP-2/Calcium Phosphate Matrix Accelerates Osteotomy-Site Healing in a Nonhuman Primate Model at Multiple Treatment Times and Concentrations. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, C.E.S.; Wohl, A.P.; Doherr, S.; Correns, A.; Sonntag, N.; Lütke, S.; Mörgelin, M.; Imhof, T.; Gebauer, J.M.; Baumann, U.; et al. Targeting of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Complexes to Heparin/Heparan Sulfate Glycosaminoglycans in Bioactive Conformation. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, E.; Valat, A.; Picart, C.; Cavalcanti-Adam, E.A. Tuning Cellular Responses to BMP-2 with Material Surfaces. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2016, 27, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, T.L.M.; Boergermann, J.H.; Schwaerzer, G.K.; Knaus, P.; Cavalcanti-Adam, E.A. Surface Immobilization of Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 via a Self-Assembled Monolayer Formation Induces Cell Differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zheng, S.; Cheng, X. Designing Hydrogel for Application in Spinal Surgery. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.S.; Lee, C.S. Nanoclay-Composite Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Gels 2024, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Jiang, H.; Lin, T.; Wang, C.; Ma, J.; Gao, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X. Microspheres in Bone Regeneration: Fabrication, Properties and Applications. Mater. Today Adv. 2022, 16, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, N.; Kang, R.; Xie, L.; Liu, X. Therapeutic Application of Hydrogels for Bone-Related Diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 998988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H. Biomimetic Hydrogel Applications and Challenges in Bone, Cartilage, and Nerve Repair. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjaminejad, S.; Farjaminejad, R.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Nanoparticles in Bone Regeneration: A Narrative Review of Current Advances and Future Directions in Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lv, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Bian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, B.; et al. Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Bone Disease Therapy: Multifunctional Platforms for Regeneration, Anti-Infection and Tumor Ablation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.Y.; Thurecht, K.J.; Whittaker, A.K.; Smith, M.T. Bioerodable PLGA-Based Microparticles for Producing Sustained-Release Drug Formulations and Strategies for Improving Drug Loading. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, L.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Current Application of Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate in Bone Repair and Its Mechanism to Regulate Osteogenesis. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 698915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, A.F.; Linhart, W.; Filke, S.; Gebauer, M.; Schinke, T.; Rueger, J.M.; Amling, M. Resorbability of Bone Substitute Biomaterials by Human Osteoclasts. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3963–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Nozaki, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Yamashita, K.; Wakabayashi, N. Exploring the Biological Impact of β-TCP Surface Polarization on Osteoblast and Osteoclast Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Scully, A.; Young, D.A.; Kim, S.; Tsao, H.; Sen, M.; Yang, Y. Enhanced Mechanical Performance and Biological Evaluation of a PLGA Coated β-TCP Composite Scaffold for Load-Bearing Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Zhu, T.; Li, J.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Ding, J. Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)-Based Composite Bone-Substitute Materials. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maadani, A.M.; Salahinejad, E. Performance Comparison of PLA- and PLGA-Coated Porous Bioceramic Scaffolds: Mechanical, Biodegradability, Bioactivity, Delivery and Biocompatibility Assessments. J. Control. Release 2022, 351, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuichi, T.; Hirai, H.; Kitahara, T.; Bun, M.; Ikuta, M.; Ukon, Y.; Furuya, M.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Janeczek, A.A.; Dawson, J.I.; et al. Nanoclay Gels Attenuate BMP2-Associated Inflammation and Promote Chondrogenesis to Enhance BMP2-Spinal Fusion. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 44, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, J.B.; Lu, L.; Zhu, X.; Porter, B.D.; Hefferan, T.E.; Larson, D.R.; Currier, B.L.; Mikos, A.G.; Yaszemski, M.J. Biological Activity of RhBMP-2 Released from PLGA Microspheres. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000, 122, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.W.; Pokorski, J.K. Poly(Lactic-co-glycolic Acid) Devices: Production and Applications for Sustained Protein Delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2018, 10, e1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, G.T.S.; White, L.J.; Rahman, C.V.; Cox, H.C.; Qutachi, O.; Rose, F.R.A.J.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Woodruff, M.A. PLGA-Based Microparticles for the Sustained Release of BMP-2. Polymers 2011, 3, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundermann, J.; Zagst, H.; Kuntsche, J.; Wätzig, H.; Bunjes, H. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (BMP-2) Aggregates Can Be Solubilized by Albumin—Investigation of BMP-2 Aggregation by Light Scattering and Electrophoresis. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaas, B.; Burmeister, L.; Li, Z.; Nimtz, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Rinas, U. Properties of Dimeric, Disulfide-Linked RhBMP-2 Recovered from E. Coli Derived Inclusion Bodies by Mild Extraction or Chaotropic Solubilization and Subsequent Refolding. Process Biochem. 2018, 67, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marom, B.; Heining, E.; Knaus, P.; Henis, Y.I. Formation of Stable Homomeric and Transient Heteromeric Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Receptor Complexes Regulates Smad Protein Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 19287–19296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodr, V.; Machillot, P.; Migliorini, E.; Reiser, J.-B.; Picart, C. High-Throughput Measurements of Bone Morphogenetic Protein/Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Interactions Using Biolayer Interferometry. Biointerphases 2021, 16, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swed, A. Protein Encapsulation into PLGA Nanoparticles by a Novel Phase Separation Method Using Non-Toxic Solvents. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddlecombe, J.G.; Smith, G.; Uddin, S.; Mulot, S.; Spencer, D.; Gee, C.; Fish, B.C.; Bracewell, D.G. Factors Influencing Antibody Stability at Solid–Liquid Interfaces in a High Shear Environment. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009, 25, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiese, S.; Pappenberger, A.; Friess, W.; Mahler, H.-C. Equilibrium Studies of Protein Aggregates and Homogeneous Nucleation in Protein Formulation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paborji, M.; Pochopin, N.L.; Coppola, W.P.; Bogardus, J.B. Chemical and Physical Stability of Chimeric L6, a Mouse-Human Monoclonal Antibody. Pharm. Res. 1994, 11, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, A.W.P.; Bremer, M.G.E.G.; Norde, W. Structural Changes of IgG Induced by Heat Treatment and by Adsorption onto a Hydrophobic Teflon Surface Studied by Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1998, 1425, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Q.; Bomser, J.A.; Zhang, Q.H. Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields and Heat Treatment on Stability and Secondary Structure of Bovine Immunoglobulin G. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkarinen, T.; Hietala, O.; Jämsä, T.; Jalovaara, P. Gamma Irradiation and Ethylene Oxide in the Sterilization of Native Reindeer Bone Morphogenetic Protein Extract. Scand. J. Surg. 2005, 94, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekkarinen, T.; Hietala, O.; Lindholm, T.S.; Jalovaara, P. Influence of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on the Activity of Native Reindeer Bone Morphogenetic Protein. Int. Orthop. 2004, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ijiri, S.; Yamamuro, T.; Nakamura, T.; Kotani, S.; Notoya, K. Effect of Sterilization on Bone Morphogenetic Protein. J. Orthop. Res. 1994, 12, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, T. BMP-2 Antagonists Emerge from Alterations in the Low-Affinity Binding Epitope for Receptor BMPR-II. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, J.; Dreyer, M.K.; Kirsch, T.; Sebald, W. The Crystal Structure of the BMP-2:BMPR-IA Complex and the Generation of BMP-2 Antagonists. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2001, 83-A (Suppl. 1), S7–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Jung, S.K.; Lee, J.; Chang, P.S.; Kang, S.H. Modulation of Osteogenic Differentiation by Escherichia Coli-Derived Recombinant Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. AMB Express 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.-H.; Esquivies, L.; Ahn, C.; Gray, P.C.; Ye, S.-K.; Kwiatkowski, W.; Choe, S. An Activin A/BMP2 Chimera, AB204, Displays Bone-Healing Properties Superior to Those of BMP2. J. Bone Min. Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarrategi, A.; Moreno-Vicente, C.; Ramos, V.; Aranaz, I.; Sanz Casado, J.V.; López-Lacomba, J.L. Improvement of Porous β-TCP Scaffolds with RhBMP-2 Chitosan Carrier Film for Bone Tissue Application. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2008, 14, 1305–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.W.H.; Ulery, B.D.; Ashe, K.M.; Laurencin, C.T. Studies of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-Based Surgical Repair. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannoury, C.A.; An, H.S. Complications with the Use of Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (BMP-2) in Spine Surgery. Spine J. 2014, 14, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.W.; LaChaud, G.; Shen, J.; Asatrian, G.; Nguyen, V.; Zhang, X.; Ting, K.; Soo, C. A Review of the Clinical Side Effects of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. Tissue Eng. Part. B Rev. 2016, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, N. Complications Due to the Use of BMP/INFUSE in Spine Surgery: The Evidence Continues to Mount. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013, 4, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Feng, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Niu, X. The Pro-Inflammatory Response of Macrophages Regulated by Acid Degradation Products of Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles. Eng. Life Sci. 2021, 21, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).