Abstract

The discovery of potent antiviral inhibitors remains a major challenge in combating viral infections. In this study, we present a hybrid computational pipeline that integrates machine learning for accurate prediction of small-molecule HIV-1 inhibitors. Five classification algorithms were trained on 7552 known inhibitors from ChEMBL using five classes of molecular fingerprints. Among these, Random Forest (RFC) models consistently outperformed the others, achieving accuracy values of 0.9526 to 0.9932, while K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) models, although slightly less accurate, still demonstrated robust performance, with accuracies ranging from 0.9170 to 0.9482 and 0.9071 to 0.9179 for selected descriptors, respectively. Based on model predictions, 4511 natural compounds from the COCONUT database were identified as potential inhibitors. After 3D shape similarity filtering (Tanimoto Combo > 1 and Shape Tanimoto > 0.8), eight top-ranked compounds were prioritized for further assessment of their physicochemical, ADMET, and drug-likeness properties. Two natural compounds, CNP0194477 and CNP0393067, were identified as the most promising candidates, showing low cardiotoxicity (hERG risk: 0.096 and 0.112), favorable hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity profiles, and good predicted oral absorption. This integrated workflow provides a robust and efficient computational strategy for the identification of natural compounds with antiviral potential, facilitating the selection of promising HIV-1 inhibitors for further experimental validation.

1. Introduction

Despite advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the cause of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), remains a significant global health challenge, with the need for continued research into new therapeutic approaches due to issues like drug resistance and long-term side effects of current antiretroviral treatments [1]. The virus progressively weakens the immune system, primarily targeting white blood cells, which increases susceptibility to opportunistic infections and certain cancers. HIV-1 has a complex life cycle in which several essential enzymes contribute to its replication: (i) Reverse Transcriptase (RT) converts viral RNA into DNA, a crucial step for integrating the viral genetic material into the host genome; (ii) Integrase (IN) facilitates the integration of this viral DNA into the host cell’s genome, allowing the virus to replicate and persist; (iii) Protease (PR) cleaves viral polypeptides, generating mature proteins necessary for the formation of viral particles [2,3].

Recent computational studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of in silico approaches in evaluating the activity and selectivity of bioactive compounds. Computational approaches in drug discovery encompass a variety of techniques, including 3D similarity, molecular docking, virtual screening, QSAR modeling, molecular dynamics simulations, pharmacophore modeling, ADMET prediction, homology modeling, free energy calculations, fragment- and ligand-based drug design, protein–protein docking, etc., all of which facilitate the identification, optimization, and evaluation of bioactive compounds [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. These strategies provide a valuable platform for the design and optimization of molecules with therapeutic potential. Such computational approaches have proven particularly useful in the context of HIV, where in silico methods support drug development and resistance prediction. Traditional techniques like molecular docking and virtual screening are employed to identify potential inhibitors of HIV enzymes and receptors, facilitating the design of antiretroviral agents by simulating interactions between drugs and viral proteins [12,13,14,15,16]. Additionally, computational models have been utilized to predict the emergence of drug resistance [17,18], enabling healthcare professionals to anticipate and mitigate treatment failures. Beyond these traditional approaches, modern computational workflows now integrate machine learning algorithms, artificial intelligence, and multi-scale modeling to improve predictive accuracy. These methods allow the rapid screening of extensive libraries of natural and synthetic compounds, the assessment of binding affinities, the prediction of pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles, and the identification of potential off-target effects. Such integrative strategies accelerate the discovery of novel HIV inhibitors, optimize combination therapies, and provide a framework for anticipating and overcoming drug resistance.

By leveraging advanced algorithms, researchers can analyse the structural and sequence features of protease inhibitors and develop models capable of predicting the effectiveness of novel compounds. Alipanahi et al. [19] employed deep learning techniques to predict the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins, providing a foundation for similar approaches in the context of HIV protease inhibition [20]. The integration phase of the HIV life cycle presents a unique set of challenges, and ML has emerged as a valuable tool for predicting the inhibition of the integrase enzyme. Ribeiro and Ortiz [21] conducted a comprehensive review highlighting the synergy between machine learning and bioinformatics models in the discovery of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors [21]. This approach can be extended to integrase inhibitors, allowing for the identification of compounds that disrupt the integrase-mediated integration of viral DNA into the host genome [22]. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors form a cornerstone of current antiretroviral therapies [23]. ML applications in predicting the inhibition of reverse transcriptase have proven invaluable in optimising drug design and understanding resistance mechanisms [24,25]. Vandekerckhove and Wensing [26] emphasised the importance of sequence analysis in predicting HIV coreceptor usage, showcasing the potential of ML to unravel intricate relationships between viral genetic variations and drug response. In addition to enzyme inhibition prediction, ML has found applications in innovative technologies for rapid detection and quantification of HIV. Koydemir et al. [27] demonstrated the use of mobile-phone-based fluorescent microscopy coupled with ML for the rapid imaging and detection of pathogens, showcasing the potential for point-of-care diagnostics and real-time monitoring of HIV treatment outcomes. Understanding the temporal aspects of the HIV widespread is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies. Korber et al. [28] utilised ML to date the precursor of HIV-1 pandemic strains, revealing valuable insights into the evolutionary history of the virus. This temporal perspective is essential for anticipating future challenges and adapting treatment approaches [29,30]. Recent advances have further highlighted the significant potential of artificial intelligence in HIV-1 research, demonstrating its ability to accelerate drug discovery, predict viral protein interactions, optimize therapeutic strategies, and enhance our understanding of viral evolution and resistance mechanisms. Uslu et al. [31] developed an AI-based multi-stage system combining molecular docking and ADME predictions to identify novel anti-HIV compounds, demonstrating strong potential for accelerating early-stage drug discovery. Their approach highlights how machine learning can efficiently prioritize candidate molecules and support rational design of antiviral agents. Jin and Zhang [32] provided a comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence applications in HIV research, highlighting recent advances in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention. Their work emphasized how AI-driven methods can accelerate drug discovery, improve prediction of therapeutic outcomes, and support precision strategies in combating HIV-1. Oyediran et al. [33] developed AI-based approaches to predict HIV mutations and guide drug design, emphasizing the potential for personalized treatment and prevention strategies. Their study demonstrated how machine learning can support precision medicine by identifying mutation-driven drug responses and optimizing therapeutic interventions. Riveros Maidana et al. [34] benchmarked machine learning models for predicting HIV-1 protease inhibitor resistance, highlighting the influence of dataset construction and feature representation on model performance. Their study provided insights into optimizing computational strategies for accurate prediction of drug resistance in HIV-1. The integration of machine learning into HIV research has paved the way for significant advances [35,36,37]. While deep learning frameworks have demonstrated strong predictive performance, they often require large datasets and are prone to overfitting when data are limited or imbalanced. To address these limitations, a hybrid ML approach that combines traditional machine learning models with deep learning components leverages the strengths of both paradigms. Traditional ML models contribute interpretability and robustness on smaller datasets, whereas deep learning captures complex, non-linear relationships in molecular features. This integration enhances predictive accuracy, reduces false positives, and improves generalizability across diverse antiviral compound datasets. Consequently, such hybrid systems provide a powerful framework for predicting the inhibition of key enzymes such as protease, integrase, and reverse transcriptase, ultimately advancing diagnostic and therapeutic developments in HIV research.

The potential of natural compounds in drug discovery and therapeutic development has led to growing interest in these molecules in recent years. The discovery of these compounds was, in the past, a long and laborious process based on trial and error. Today, researchers use advanced computational tools to accelerate this work. They can now virtually analyze thousands of natural compounds, predicting which ones are most likely to be effective against specific diseases [38,39]. This strategy allows them to efficiently prioritize potential active compounds, which can then be tested in the laboratory. Combining traditional knowledge with modern technologies opens new avenues for identifying novel and effective therapeutic agents.

Natural compounds have garnered considerable attention in HIV drug discovery due to their structural diversity and ability to target multiple stages of the viral life cycle. Their unique properties allow them to interact with various viral components, offering a promising approach for more effective and comprehensive therapies. The natural origin of these compounds also reduces the likelihood of developing resistance, making them valuable candidates for innovative treatments [40].

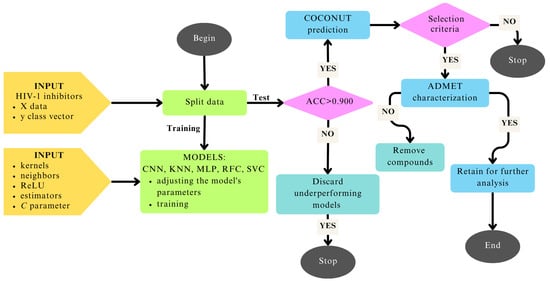

The main purpose of this study is to develop robust and predictive computational models to identify natural compounds as multi-target inhibitors of the three essential HIV-1 enzymes: integrase (IN), protease (PR), and reverse transcriptase (RT). This is achieved through an automated workflow that integrates two deep learning approaches (CNN: Convolutional Neural Network and MLP: Multi-Layer Perceptron) and three machine learning algorithms (KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors, RFC: Random Forest Classifier, and SVC: Support Vector Classifier). To achieve this goal, the study was conducted in six main steps: (i) HIV-1 inhibitors were downloaded from ChEMBL and the data were preprocessed; (ii) five types of molecular fingerprints (Atom Pairs 2D, E-state, MACCS, PubChem, and Substructure) were generated; (iii) machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models were trained, validated, and tested; (iv) 3D shape similarity evaluation was performed, (v) comprehensive ADMET profiling was conducted; and (vi) the results were analyzed and discussed, with conclusions summarizing the main findings and implications for HIV-1 management (Figure 1). To the best of our knowledge, this integrated approach, which combines the selected models (CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC), five types of molecular fingerprints (Atom Pairs 2D, E-state, MACCS, PubChem, and Substructure), 3D shape similarity evaluation, and comprehensive pharmacokinetic profiling, has not yet been described in previous studies.

Figure 1.

Step-by-step workflow illustrating the methodology applied for compound screening and evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

The computations were carried out using a computing infrastructure configured with the following GPUs: (i) NVIDIA RTX A2000, TSMC Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited, Hsinchu Science Park in Hsinchu, Taiwan running on Windows 11 for KNN and SVC; (ii) NVIDIA RTX 2070, TSMC Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited, Hsinchu Science Park in Hsinchu, Taiwan running on an Ubuntu Linux 22.04 for CNN and MLP; (iii) NVIDIA RTX 3060, TSMC Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited, Hsinchu Science Park in Hsinchu, Taiwan running on Windows 11 for RFC.

The execution time for CNN is 1 h/descriptor, for KNN is 30 h/descriptor, for MLP is 1 h/descriptor, for RFC is 10 h/descriptor, and for SVC is 12 h/descriptor.

The computations involved training, plotting history diagrams, performance metric computations, and plottings, of the five models (CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC) on the ChEMBL data sets and pIC50 predictions on (i) ChEMBL and (ii) CoCoNut are depicted in Figure 1.

2.1. Dataset Preparation: Assembly, Preprocessing, and Splitting into Training, Test, and Validation

In total, 7528 molecules inhibiting HIV-1 enzyme (IN, PR, RT) were filtered from the ChEMBL 33 database [41]. These molecules were refined by removing duplicate entries and filtering based on experimentally determined pIC50 values expressed in nanomolar (nM) units to ensure accuracy and consistency. Data points with precise IC50 values, those reported with the relational “=” symbol, were retained. For each compound, the lowest reported pIC50 value was retained, regardless of the number of experimental determinations. In classification models, compounds with IC50 values of 1000 nM or lower (pIC50 ≥ 6) were labeled as active, while those with IC50 values of 10,000 nM or higher (pIC50 ≤ 5) were considered inactive. Molecules with IC50 values ranging from 1001 to 9999 nM (pIC50 between 4.999 and 5.999) were classified as intermediate and subsequently removed. After applying the filtering criteria, the dataset was reduced to 7528 inhibitors, which were then divided into training, testing, and validation sets in order to build the ML models. A total of 24 molecules were added from the Approved Drugs database, forming a set of 7552 molecules in total.

Each data set was decomposed into 80% for training and validation and 20% for testing. The 80% is split 10 times in 72% for training and 8% for validation. Each data set will have 10 models trained on the 10 different splits.

2.2. Molecular Descriptors: Calculation

The structural features of chemical compounds and their representation in a numerical format were extracted by converting SMILES into 5 types of fingerprints (Atom Pairs 2D, E-state, MACCS, PubChem, and Substructure). Specifically, Atom Pairs 2D (780 bits) describe pairs of atoms and their topological distances, E-state (79 bits) encodes the electronic state and topological environment of atoms, MACCS (166 bits) indicates the presence of specific functional groups, PubChem (881 bits) captures common substructures from the PubChem database, and Substructure fingerprints (307 bits) identify particular structural motifs. These fingerprints were selected to capture complementary structural and electronic features of the molecules. In total, this process generated a comprehensive set of descriptors for each compound, providing a rich numerical representation suitable for machine learning modeling. Descriptors were preprocessed through normalization and filtering to remove low-variance or highly correlated features, ensuring compatibility with the training, validating, and testing of machine learning models. These molecular fingerprints were generated using the open-source software PaDEL-Descriptor [42], which provides a wide range of 1D, 2D, and fingerprint-based molecular descriptors commonly used in cheminformatics and machine learning applications. This step allowed the transformation of data into a suitable form, making it compatible with training, validating, and testing of machine learning models, as well as for virtual screening (VS) applications. The combination of multiple fingerprint types ensures a robust and diverse representation of molecules, enhancing the predictive performance of the models.

2.3. Machine Learning Models: Development, Validation, and Performance Metrics

2.3.1. DL and ML Development

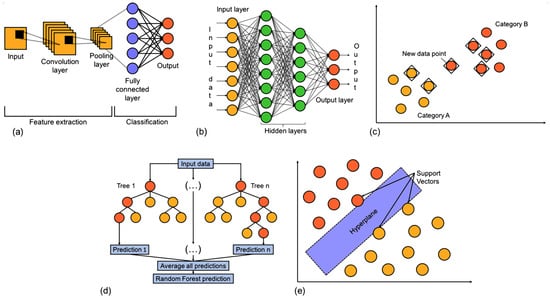

The analysed datasets include data-HIV1 with 7552 lines (inhibitors) and a variable number of binary columns (fingerprints) from 79 to 881 as input vector ‘x’, while the ‘y’ vector comprises binary values, where ‘1’ indicates active (IC50 values equal to or less than 1000 nM) compounds and ‘0’ denotes inactive (IC50 greater than or equal to 10,000 nM) compounds. The machine learning models were built using specific parameters that define their architecture and functioning, including the number of estimators, kernel type, regularization strength, learning rate, etc. A detailed overview of the parameters used for each model is provided in Table 1 and Figure 2. Additionally, for models such as MLP, the Adam optimizer was applied with binary crossentropy loss, while other models were optimized through systematic hyperparameter tuning using cross-validation to select the best-performing configurations. This approach ensures robust training and reproducibility of results. For each model, the number of variations or trained models and the specific parameters explored during training are listed.

Table 1.

Parameters used for each machine learning model.

Figure 2.

General overview of the classification models used: (a) Convolutional Neural Network; (b) Multilayer Perceptron; (c) K-Nearest Neighbor Classifier; (d) Random Forest Classifier; (e) Support Vector Classifier.

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

CNN is a type of deep learning model particularly effective in identifying local patterns in structured data, such as molecular descriptors or feature matrices. Unlike traditional feedforward neural networks, CNNs use convolutional layers to automatically extract important features from input data by applying learnable filters across local regions. This local connectivity enables the network to detect spatial or sequential dependencies, making CNNs suitable for tasks beyond image processing [43], including bioinformatics and cheminformatics. The architecture typically includes convolutional layers, activation functions (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid), pooling layers for dimensionality reduction, and fully connected layers for classification or regression tasks. CNNs are efficient, scalable, and capable of capturing complex relationships within molecular data, making them valuable tools for drug discovery applications such as inhibitor classification [44,45,46,47].

K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

KNN is a classification algorithm that works by analyzing the proximity of a new, unlabelled data point to existing labeled data in the feature space [48]. Specifically, the algorithm calculates the distance between the new point and all training samples using a metric distance [49] such as the Euclidean or Manhattan.

Once distances are calculated, the algorithm selects the k-closest training instances (neighbors) and considers their corresponding class labels. The new data point is then assigned to the class that appears most frequently among the k neighbors, a process known as majority voting. KNN is a non-parametric, instance-based learning method that assumes similar data points are likely to share the same class. The choice of k significantly affects model performance: a small k can lead to high variance (overfitting), while a large k may increase bias (underfitting) [50]. Therefore, k is usually determined empirically to find a balance between bias and variance.

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

MLP is a type of feedforward artificial neural network designed to map input data to corresponding outputs. Unlike the standard linear perceptron, an MLP incorporates three or more layers of neurons with nonlinear activation functions. This capability allows it to model complex patterns and effectively handle non-linearly separable data. MLPs are versatile and powerful nonlinear models, with their complexity determined by the number of layers and neurons within each layer. It has been proven that, given sufficient hidden units and training data, MLPs can approximate virtually any function with the desired level of accuracy [51].

Random Forest Classifier (RFC)

RFC is an ensemble method that builds multiple decision trees on random subsets of the training data to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting. Trees use the “best” splitter and can be trained with or without bootstrap sampling. RFC natively handles missing values by learning during training how to route them based on information gain; during prediction, missing values follow these learned paths or go to the majority child node if unseen before. Final predictions aggregate individual tree outputs, classification uses the majority vote, and regression uses the average [52].

Support Vector Classifier (SVC)

SVC is a supervised learning algorithm based on SVM, designed to separate data into classes by finding the optimal hyperplane with the maximum margin. In the linear case, this boundary is a straight line (or hyperplane), while in nonlinear cases, SVC uses kernel functions to project data into higher-dimensional spaces, enabling more complex decision boundaries. SVC relies on a few support vectors, the most informative training points, and balances margin maximization with classification error control via the regularization parameter C. It is widely used due to its robustness, accuracy, and flexibility in handling both linearly and non-linearly separable data [53].

Following the definition and parameter optimization of five selected machine learning and deep learning models (CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC), a comprehensive and automated workflow was developed in Python using TensorFlow 2.10 [54]. This pipeline integrates all essential steps required for virtual screening in the context of natural compounds selection, including data preprocessing, molecular fingerprint encoding, model training, cross-validation, performance evaluation (using metrics such as ACC, AUC, F1-score, etc.), and final prediction of candidate compounds. The modular structure (Figure 3) of the workflow enables flexibility in model comparison and easy extension for future applications. The classes represent key components involved in data handling, model configuration, metrics computation, and result generation. The use of object-oriented programming (OOP) principles ensures that each component is encapsulated, promoting reusability and maintainability. This design allows seamless integration of additional machine learning or deep learning models without requiring major modifications to the existing code-base. Moreover, the clear separation of responsibilities between classes improves code readability and facilitates debugging, testing, and collaborative development. Overall, this modular OOP approach provides a robust and scalable framework, supporting both current virtual screening tasks and future expansions of the hybrid pipeline.

Figure 3.

UML class diagram representing the structure of the ML/DL pipeline used in the virtual screening process.

2.3.2. DL and ML Validation

This method involves partitioning the dataset into ten equal subsets, where each subset is used once as the validation data while the remaining nine subsets are used for training. The process is repeated ten times (Figure S1), and the performance metrics are averaged across all folds to reduce the risk of overfitting and provide a reliable estimate of model accuracy.

2.3.3. Performance Metrics

Performance metrics are essential tools for assessing the accuracy, reliability, and robustness of predictive methods in computational research [55]. They provide quantitative measures that allow model comparison, parameter optimization, and ensure consistent performance across a wide range of approaches, from QSAR and molecular docking to virtual screening and other simulation-based strategies. The evaluation of DL and ML models’ performance across all data sets was conducted using multiple metrics, including accuracy (ACC), precision (PR), specificity (SP), recall (REC), F1-score (F1), the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), balanced accuracy (BACC), Cohen’s kappa, and geometric mean (G-Mean), providing a comprehensive assessment of model reliability and robustness (see Equation in Supplemntary Materials).

For CNN and MLP, metrics such as AUC are particularly valuable for assessing probabilistic outputs and model robustness, while F1-Score and MCC balance PR and REC in imbalanced settings. KNN’s sensitivity to class imbalance makes BACC and G-Mean critical for evaluation. SVC benefits from detailed analysis via PR, REC, and AUC, given its margin-based classification approach. RFC, known for stability and interpretability, was assessed through ACC, MCC, AUC, and feature importance to understand both performance and contributing factors.

2.3.4. DL and ML Predictions

Following statistical evaluation during the validation and testing phases, the DL and ML models demonstrating the highest predictive performance were identified and retained. Subsequently, these selected models were employed to predict the activity of an external natural compounds dataset, classifying each compound as either active (1) or inactive (0). This methodological approach ensured both the statistical rigor and the validity of the obtained results.

2.4. Shape-Similarity Search

In this study, Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures (ROCS v.3.7.0.1, OpenEye Scientific Software Inc., Santa Fe, NM, USA, www.eyesopen.com) [56] was employed as an advanced method for assessing three-dimensional molecular similarity. The technique uses atom-centered Gaussian functions to represent molecular volumes, providing smooth and continuous contours, which reduces the number of local maxima and allows rapid identification of optimal overlaps. In addition to shape analysis, ROCS incorporates chemical-type information by assigning specific “colors” to functional groups (e.g., hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, aromatic rings), enhancing the accuracy of the matching. This combination of geometric and chemical similarity makes ROCS a powerful tool for virtual screening and ligand design.

2.5. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) Characterization

The compounds previously predicted as active by the best-performing models and exhibiting the highest shape similarity to approved HIV drugs were further analyzed for their ADMET properties using ADMETlab 3 [57] and QikProp (Schrödinger Release 2024-4: QikProp, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA, 2024).

According to the QikProp manual, drug-like molecules should exhibit mol_MW (molecular weight) of 130–725 Da, SASA (total solvent-accessible surface area) 300–1000 , FOSA (hydrophobic component of SASA) 0–750 , FISA (hydrophilic/polar component of SASA) 7–330 , PISA (, aromatic surface area) 0–450 , PSA (polar surface area) 7–200 , donorHB (number of hydrogen-bond donors) 0–6, accptHB (number of hydrogen-bond acceptors) 2–20, QPlogPo/w (octanol/water partition coefficient, lipophilicity) between −2 and 6.5, QPlogS (aqueous solubility) above −6.5, QPlogHERG (predicted inhibition of hERG channels, safety) above −5, and good permeability indicated by QPPCaco (Caco-2 cell permeability) and QPPMDCK (MDCK cell permeability) > 500 nm/s, with predicted human oral absorption > 80%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Metrics Results

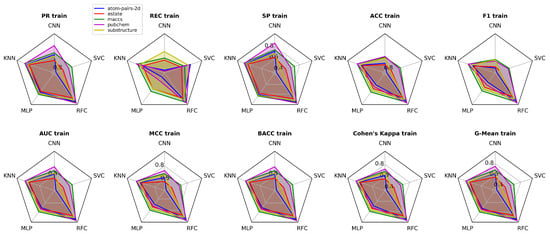

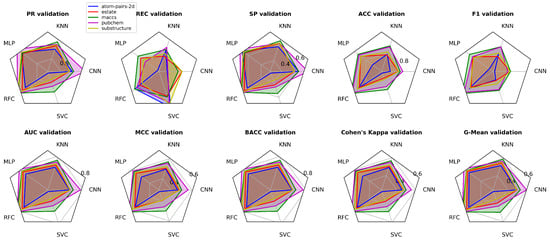

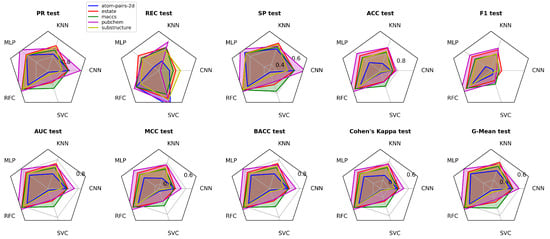

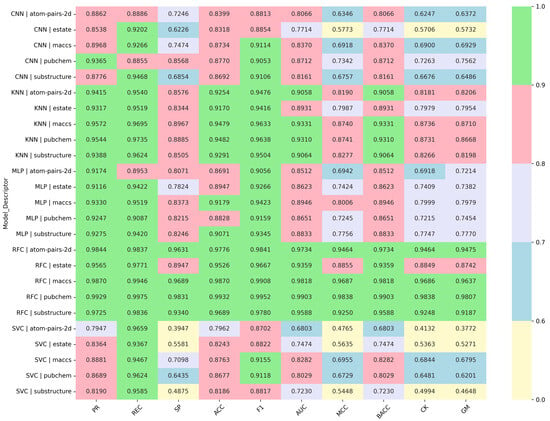

The comparative distribution of performance metrics across the three evaluation phases (training, validation, and test) is illustrated in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, offering a multidimensional perspective on the model’s predictive capability. Complementing this visual representation, Figure 7 reports the values obtained during the training phase, which serve as the baseline for further validation and testing assessments.

Figure 4.

Performance metrics (PR, REC, SP, ACC, F1, AUC, MCC, BACC, Cohen’s Kappa, G-Mean) in training phases for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

Figure 5.

Performance metrics (PR, REC, SP, ACC, F1, AUC, MCC, BACC, Cohen’s Kappa, G-Mean) in validating phases for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

Figure 6.

Performance metrics (PR, REC, SP, ACC, F1, AUC, MCC, BACC, Cohen’s Kappa, G-Mean) in testing phases for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

Figure 7.

Performance metrics (PR, REC, SP, ACC, F1, AUC, MCC, BACC, Cohen’s Kappa, G-Mean) in training phase for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

Based on the defined thresholds, RFC with Atom Pairs 2D demonstrates outstanding performance across all metrics, as every score exceeds 0.96, indicating excellent accuracy, robustness, and balance between sensitivity and specificity. KNN also performs at a very high level, with excellent precision (0.9415) and recall (0.954), while its specificity (0.8576) and MCC (0.819) remain very good. MLP achieves consistently very good results, with excellent precision (0.9174) and strong recall (0.8953), though its G-Mean (0.7214) indicates only marginal balance. CNN shows moderate performance, with recall and precision in the very good range but reduced specificity (0.7246) and a lower MCC (0.6346), suggesting limited reliability. Finally, SVC, despite its excellent recall (0.9659), performs poorly overall due to extremely low specificity (0.3947), MCC (0.4765), and G-Mean (0.3772), reflecting severe class imbalance and overprediction of positives.

Using the E-state descriptor, RFC again demonstrates excellent overall performance, with most metrics above 0.94 and specificity at 0.8947, indicating a strong and well-balanced predictive capability. KNN ranks second, delivering excellent precision (0.9317) and recall (0.9519), while its specificity (0.8344) and MCC (0.7987) remain in the very good range but indicate slightly reduced balance. MLP achieves very good results overall, with precision (0.9116) and recall (0.9422) rated excellent, yet its specificity (0.7824) and G-Mean (0.7382) are only acceptable, lowering its robustness. CNN shows limited balance, with recall (0.9202) at an excellent level but specificity (0.6226) and MCC (0.5773) rated poor, suggesting strong bias. Finally, SVC demonstrates the weakest performance, despite excellent recall (0.9367), due to very low specificity (0.5581), poor MCC (0.5635), and G-Mean (0.5271), indicating a severe imbalance and strong tendency to overpredict the positive class.

With the MACCS descriptor, RFC exhibits near-perfect and consistently excellent performance across all metrics, with values above 0.96, confirming its superior balance and predictive power. KNN secures second place, achieving excellent precision (0.9572) and recall (0.9695), though specificity (0.8967) and MCC (0.874) remain slightly lower, indicating very good but not flawless balance. MLP follows with very good precision (0.933) and recall (0.9519), while its specificity (0.8373) and MCC (0.8006) are also very good, though less robust than KNN. SVC, despite excellent recall (0.9467), suffers from reduced specificity (0.7098) and an MCC of 0.6955, placing it in the acceptable range and signaling imbalance. CNN performs similarly to SVC, with specificity (0.7474) and G-Mean (0.6929) slightly higher, yet still only acceptable, and far from the reliability demonstrated by RFC and KNN.

Using the PubChem descriptor, RFC delivers exceptional and nearly perfect performance across all metrics, with values above 0.98, confirming its unmatched robustness and predictive reliability. KNN secures second place with excellent precision (0.9544) and recall (0.9735), though its specificity (0.8885) and MCC (0.8741) remain slightly weaker, indicating very good but less balanced predictions compared to RFC. MLP shows a notable performance drop, with precision (0.9247) and recall (0.9087) in the excellent and very good range, but specificity (0.8215), MCC (0.7245), and G-Mean (0.7454) only acceptable, reducing overall consistency. CNN performs similarly to MLP but with slightly better specificity (0.8568) and G-Mean (0.7562), suggesting a somewhat more balanced profile despite a lower recall (0.8855). SVC shows the weakest performance, combining excellent recall (0.9624) with poor specificity (0.6435) and G-Mean (0.6201), highlighting a severe imbalance and strong positive class bias.

With the Substructure descriptor, RFC demonstrates excellent performance across all metrics, with precision (0.9725), recall (0.9836), specificity (0.934), and MCC (0.925) all above 0.9, confirming its strong balance and reliability. KNN ranks second, delivering excellent precision (0.9388) and recall (0.9624), while its specificity (0.8505) and MCC (0.8277) remain very good but clearly below RFC. MLP achieves very good results, with precision (0.9275), recall (0.942), and specificity (0.8246) in the upper range, though MCC (0.7756) and G-Mean (0.777) indicate only acceptable robustness. CNN shows significant imbalance, with excellent recall (0.9468) but weak specificity (0.6854), resulting in MCC (0.6757) and G-Mean (0.6486) rated poor. Finally, SVC delivers the least reliable performance, combining high recall (0.9585) with extremely low specificity (0.4875) and very poor G-Mean (0.4648), confirming a strong positive bias and lack of generalization.

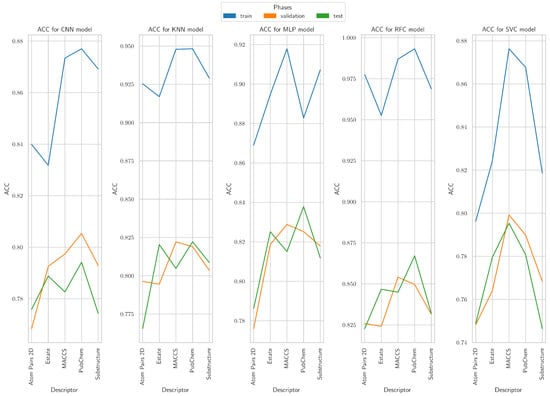

3.2. Accuracy Results

The ACC values derived from PubChem and MACCS descriptors were consistently higher across training, validation, and test phases, confirming robust predictive capability throughout the evaluation pipeline (Figure 8). A detailed analysis reveals that (i) PubChem achieved the highest ACC for the CNN model across all phases; (ii) for KNN, PubChem and MACCS provided the strongest performance, particularly in validation and test stages; (iii) in the MLP model, MACCS and PubChem outperformed other descriptors, especially during training and test; (iv) for RFC, PubChem achieved the highest ACC across all phases, closely followed by MACCS, indicating strong generalization; and (v) in the case of SVC, MACCS consistently delivered the best ACC, while Atom Pairs 2D and Substructure descriptors remained considerably weaker.

Figure 8.

Accuracy results in training, validating, and testing phases for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

Overall, PubChem and MACCS were the most effective descriptors across all models, whereas Atom Pairs 2D, E-state, and Substructure frequently resulted in lower ACC, particularly in validation and test phases. Among the models, RFC achieved the highest ACC values across descriptors and phases, outperforming CNN, KNN, MLP, and SVC.

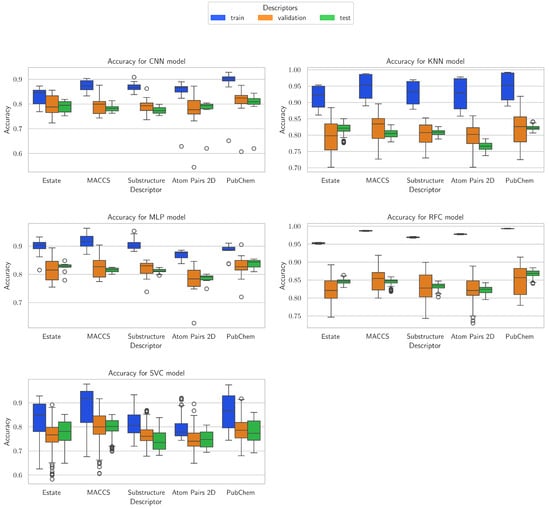

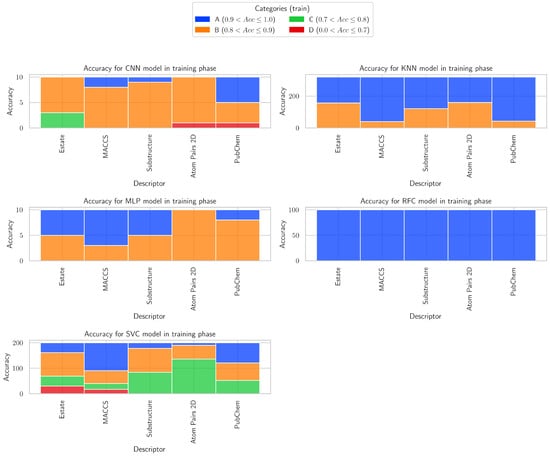

3.3. Accuracy Distribution

Following the analysis of performance metrics and the examination of accuracy results across all three evaluation phases (training, validation, and testing), the accuracy distribution for the five models (Figure 9) was analyzed, providing detailed insights into the variability of predictive performance depending on the descriptors used and each model’s architecture. Analysis of the validation and test phases allows comparison of these patterns on unseen data, highlighting the consistency, robustness, and generalization capability of each model. This approach offers a comprehensive perspective on model performance throughout the entire learning process.

Figure 9.

Accuracy distribution in training phase for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

For the CNN model, the E-state, MACCS, Substructure, and PubChem descriptors show the most consistent performance across training, validation, and test phases. E-state and Substructure descriptors provide balanced results with moderate variability, while MACCS and PubChem achieve slightly higher training performance but show some drop in validation and test phases. Atom Pairs 2D is less stable, with higher standard deviations and wider ranges between minimum and maximum values, making it less reliable across phases.

For KNN, MACCS, PubChem, and Substructure descriptors perform best, achieving high training values and maintaining solid validation and test performance, indicating strong generalization. E-state descriptors are moderately strong, showing some drop from training to test, and Atom Pairs 2D performs weakest, with lower test values compared to training. Overall, KNN demonstrates that MACCS and PubChem are its most robust descriptors across all phases.

For MLP, MACCS, PubChem, and Substructure descriptors stand out for delivering high training and relatively stable validation and test results. E-state descriptors are slightly lower in performance but remain consistent, while Atom Pairs 2D is more variable, showing a noticeable drop from training to validation. PubChem in particular maintains strong test performance, highlighting its reliability with MLP across phases.

For RFC, all descriptors perform exceptionally well, with PubChem, Atom Pairs 2D, MACCS, and Substructure achieving nearly perfect training results and strong validation and test performance. E-state descriptors are also very good, though slightly lower than the top-performing descriptors. RFC shows minimal drop from training to test, indicating excellent generalization and low variability across phases.

For SVC, MACCS and E-state descriptors are the most effective, providing higher training values and relatively stable validation and test performance. Substructure, PubChem, and Atom Pairs 2D descriptors show more variability and lower test values, indicating that SVC is more sensitive to descriptor choice and benefits from descriptors with stronger structure-related information.

3.4. Accuracy Categories

The accuracy categories of each descriptor within the context of each model are presented in Figure 10, providing a detailed overview of the contribution of different descriptors to model performance. Accuracy is classified into four categories—excellent (0.9–1.0), very good (0.8–0.9), acceptable (0.7–0.8), and poor (<0.7)—highlighting patterns of high, medium, and low predictive performance across all models.

Figure 10.

Accuracy categories in training phase for CNN, KNN, MLP, RFC, and SVC models.

For CCN, E-state is mostly in category B (7) with a few in C (3), MACCS is primarily in B (8) with a small presence in A (2), Substructure is dominated by B (9) with only one in A, Atom Pairs 2D is strongly in B (9) with one in D, and PubChem is more balanced with A (5) and B (4) plus one in D.

For KNN, E-state is split between A (163) and B (157) with none in C or D, MACCS is heavily concentrated in A (280) with fewer in B (40), Substructure is mainly in A (199) with a smaller share in B (121), Atom Pairs 2D is evenly divided between A (160) and B (160), and PubChem is dominated by A (277) with some in B (43).

For MLP, E-state is evenly split between A (5) and B (5), MACCS leans toward A (7) with some in B (3), Substructure is also evenly divided between A (5) and B (5), Atom Pairs 2D is entirely in B (10), and PubChem is mostly in B (8) with a small presence in A (2).

For RFC, E-state is entirely in A (100), MACCS is entirely in A (100), Substructure is entirely in A (100), Atom Pairs 2D is entirely in A (100), and PubChem is entirely in A (100).

For SVC, E-state is spread across B (92), A (39), C (39), and D (30), MACCS is strongest in A (110) with B (50), C (23), and D (17) also present, Substructure is mainly in B (94) and C (84) with some in A (22), Atom Pairs 2D is dominated by C (136) with smaller shares in B (54) and A (10), and PubChem is fairly distributed across A (79), B (69), and C (52).

Looking across all descriptors, RFC shows the most decisive and consistent category predictions, often concentrating all or the vast majority of counts in a single category, while models like CNN, MLP, and SVC show more spread and ambiguity across categories, and KNN tends to favor A but with some spread. This suggests that RFC is the most confident and reliable model for categorical assignments in these data sets.

3.5. Selection Framework for High-Performing Predictive Models

Analyzing the average values of the performance metrics for each model (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4), RFC clearly stands out, achieving the highest precision, recall, accuracy, F1-score, AUC, and balanced metrics such as MCC, BACC, and G-Mean, which indicates robust and well-balanced classification. KNN and MLP also perform very well, with high precision and recall and reasonably balanced specificity, showing they are reliable alternatives. CNN shows slightly lower specificity and MCC, resulting in more false negatives, while SVC exhibits high recall but low specificity, reflecting a tendency to overpredict positives. Overall, RFC is the most robust model, with KNN and MLP as strong contenders.

Table 2.

Average performance metrics for each ML and DL model across all descriptors in the training phase.

Table 3.

Average performance metrics for each ML and DL model across all descriptors in the validation phase.

Table 4.

Average performance metrics for each ML and DL model across all descriptors in the testing phase.

After in-depth evaluation of all performance metrics, Random Forest (RFC) models consistently demonstrated superior predictive capability across all five molecular descriptors, with accuracy values ranging from 0.9526 to 0.9932 and MCC exceeding 0.8855. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) models also exhibited robust performance across all descriptors (ACC = 0.9170–0.9482, MCC = 0.7987–0.8741), representing a reliable alternative. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) models achieved ACC > 0.9 for the MACCS and Substructure descriptors, with correspondingly high F1-scores and MCC values, indicating that they are effective and balanced for these two descriptors (Table 5). Considering the full spectrum of evaluation criteria, RFC is identified as the optimal model for accurate and balanced classification of inhibitors, with KNN as a strong secondary option and MLP as an effective descriptor-specific alternative (RFC (five descriptors) > KNN (five descriptors) > MLP (two descriptors)).

Table 5.

Top model-descriptor combination in the training phase.

Performance decreased slightly for all models compared to the training phase, reflecting the generalization to unseen data. RFC maintained the highest ACC (0.8370) and F1-score (0.8858), although recall (0.9027) and specificity dropped compared to training. MLP and KNN remained competitive, with ACC values of 0.8133 and 0.8071, respectively, and balanced F1-scores (0.8660 and 0.8650, respectively). CNN and SVC showed lower metrics, particularly SVC with SP = 0.4218 and MCC = 0.4107, indicating potential overfitting during training or sensitivity to data distribution changes.

On the test set, RFC continued to outperform all other models (ACC = 0.8427, F1 = 0.8863, MCC = 0.6344), demonstrating strong generalization capabilities. KNN and MLP again achieved comparable results, though slightly lower than RFC, with ACC of 0.8043 (KNN) and 0.8152 (MLP) and F1-scores 0.8598 and 0.8649, respectively. CNN showed moderate predictive ability (ACC 0.7832, F1 0.8406), while SVC remained the least robust across most metrics (ACC = 0.7702, F1 = 0.8445, MCC = 0.4446), confirming its sensitivity to dataset characteristics.

Across all phases, Random Forest (RFC) demonstrates consistently high performance, with accuracy (ACC) ranging from 0.9759 in training to 0.8427 in testing, F1-score from 0.9830 to 0.8863, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) from 0.9419 to 0.6344, indicating excellent overall predictive ability, strong balance between sensitivity and specificity, and reliable classification of potential HIV-1 inhibitors. KNN and MLP provide competitive performance, with ACC ranging from 0.9335 (KNN) and 0.8943 (MLP) in training to 0.8043 (KNN) and 0.8152 (MLP) in testing, and F1-scores from 0.9533–0.8649 (KNN) and 0.9250–0.8649 (MLP), demonstrating good predictive power with reasonable generalization, offering interpretable and simpler alternatives to RFC. CNN achieves moderate performance, with ACC ranging from 0.8583 in training to 0.7832 in testing and F1-score from 0.8988 to 0.8406, suggesting that while it captures relevant features, further hyperparameter tuning or more training data could improve robustness. SVC shows lower robustness, particularly in specificity (SP 0.5587 in training to 0.4531 in testing) and MCC (0.5906 to 0.4446), highlighting limitations in balanced prediction and reduced reliability for this task. In summary, ACC values indicate the proportion of correctly classified compounds, F1-scores reflect the balance between precision and recall, and MCC provides a robust measure of classification quality, particularly for imbalanced datasets, confirming RFC as the most reliable model, followed by KNN and MLP, while CNN and SVC are less robust for predicting potential HIV-1 inhibitors.

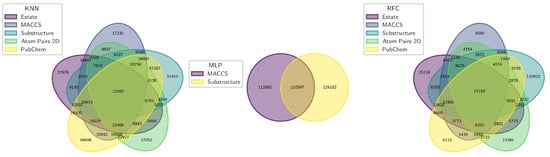

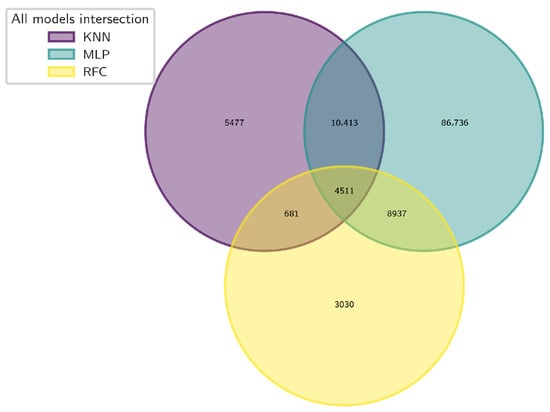

3.6. Selection and Comprehensive Characterization of Natural Compounds

The compound selection workflow consisted of multiple steps designed to increase predictive reliability and prioritize drug-like candidates. In the first stage, three machine learning models, RFC, KNN, and MLP, were independently applied to classify compounds as active or inactive. For each model, the most confidently predicted active compounds were extracted based on significant molecular descriptors influencing classification. To capture consensus and reduce model-specific bias, a two-step Venn diagram approach was implemented. The first intersection identified compounds commonly ranked as top candidates within each model (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Venn diagram showing the overlap of compounds identified as active by each machine learning model: RFC, KNN, and MLP.

Subsequently, a second Venn analysis was performed on these subsets, yielding a consensus set of 4511 natural compounds consistently predicted as active by all three models (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Venn diagram showing the overlap of compounds identified as active by three machine learning models: RFC, KNN, and MLP.

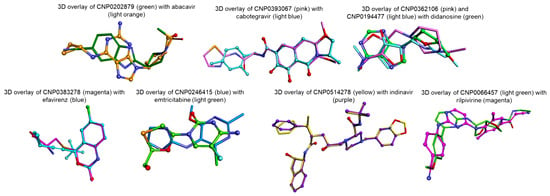

Following the selection of natural compounds using the top-performing machine learning models, a 3D shape-based similarity analysis was conducted with Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures (ROCS) [56], a widely used approach for identifying molecules with comparable spatial arrangements [58,59,60,61]. Approved HIV-1 drugs served as query compounds and were prepared with Omega (OMEGA 5.1.0.0: OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences, Santa Fe, NM, USA. http://www.eyesopen.com) [62] by selecting their lowest-energy conformers. The natural compounds were similarly prepared with Omega, generating up to 200 default conformers per molecule prior to comparison with the query drugs.

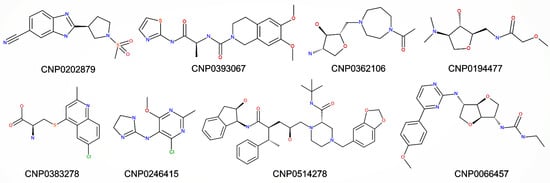

Out of the 33 FDA-approved anti-HIV drugs used as query compounds, only abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, and rilpivirine yielded natural compounds that satisfied both the Tanimoto Combo (TC > 1) [63] and Shape Tanimoto (ShT > 0.8) [64,65] thresholds. After applying these thresholds, eight natural compounds were identified as top potential candidates (Figure 13 and Figure 14). These compounds were further analyzed to determine their physicochemical characteristics, predicted oral bioavailability, and potential toxicity profiles.

where

is the i-th compound in the initial dataset;

is the Tanimoto Combo score of compound i;

is the Shape Tanimoto score of compound i;

“and” indicates that both thresholds must be satisfied for a compound to be selected.

Figure 13.

Two-dimensional structures for selected natural compounds.

Figure 14.

Top-ranked candidate molecules (sticks) illustrating 3D similarity to the reference HIV-1-approved drugs: abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, and rilpivirine (ball-and-stick).

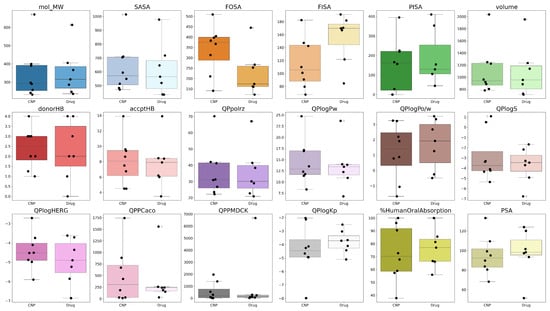

The comparison of natural compounds (CNP0362106, CNP0194477, CNP0383278, CNP0246415, CNP0514278, CNP0066457, CNP0202879, CNP0393067) versus approved drugs (abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, and rilpivirine) across QikProp recommended ranges is shown in Figure 15, highlighting differences and similarities in their physicochemical and ADME properties. Each subplot displays the distribution of a specific property, including physicochemical parameters (mol_MW, SASA, FOSA, FISA, PISA, volume), the number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and relevant ADME descriptors (QPlogPo/w, QPlogBB, QPPMDCK, %HumanOralAbsorption, etc.).

Figure 15.

Comparative analysis of computed QikProp properties for natural compounds (CNPs) versus approved drugs (abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, rilpivirine).

The calculated QikProp properties provide a detailed overview of both the natural compounds and the approved HIV drugs. Molecular weight (mol_MW) is generally within range for most compounds, though large CNPs like CNP0514278 approach the upper limit, similar to indinavir. Total solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) and volume correlate with molecular size, with larger molecules exhibiting higher surface area and volume, potentially reducing membrane permeability. Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic component of the SASA indicate balanced hydrophobic and polar surface areas in most molecules, while aromatic surface area reflects higher aromatic surface in CNPs, potentially enhancing target interactions but sometimes limiting solubility. Van der Waals surface area (PSA) is mostly within the recommended range, supporting favorable permeability. Hydrogen-bonding capacity (donorHB, accptHB) is adequate for most molecules, promoting solubility and target interactions. Lipophilicity (QPlogPo/w) and polarizability (QPpolrz/w) fall within recommended values, balancing membrane diffusion and solubility, while aqueous solubility (QPlogS) is generally acceptable. QPlogHERG indicates that some CNPs (CNP0514278) may pose hERG inhibition risks, similar to certain drugs (indinavir, rilpivirine, cabotegravir). Permeability parameters (QPPCaco and QPPMDCK) highlight significant variability: only a subset of CNPs and drugs, such as CNP0246415 and efavirenz, meet these criteria, whereas larger molecules like CNP0514278, and indinavir, show poor predicted absorption. QPlogKp values suggest that blood–brain barrier penetration is favorable for small, less polar molecules. %HumanOralAbsorption is high for CNP0066457, CNP0246415, and CNP0393067, as well as for efavirenz, rilpivirine, and cabotegravir, while CNP0194477, CNP0202879, CNP0362106, CNP0383278, CNP0514278, and the HIV drugs didanosine, emtricitabine, and indinavir exhibit moderate absorption (25–80%). Overall, while CNPs display greater structural diversity than approved drugs, many comply with QikProp-recommended ranges, but attention to permeability and hERG safety is crucial for optimizing drug-likeness.

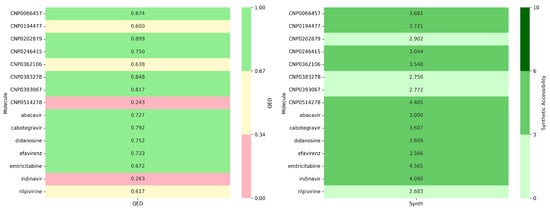

The selected natural compounds were evaluated in terms of their pharmaceutical properties using ADMETlab3. In particular, the drug-likeness (QED) and synthetic accessibility (Synth) metrics were assessed: compounds with QED > 0.67 are considered attractive, those with QED between 0.34–0.67 are less favorable, and QED < 0.34 indicates excessive complexity. Regarding synthesis, a Synth score < 3 indicates very easy to synthesize, 3–6 corresponds to easy–moderate to synthesize, and >6 indicates difficult to synthesize. This analysis enabled the selection of compounds with an optimal balance between pharmacological potential and synthetic feasibility (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Comparative analysis of computed medicinal chemistry parameters for natural compounds (CNPs) versus approved drugs (abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, rilpivirine).

The comparative analysis between natural compounds (CNP series) and FDA-approved drugs based on QED (drug-likeness) and synthetic accessibility (Synth) reveals that several natural compounds exhibit superior properties compared to current drugs. The average QED of CNPs (0.69) is slightly higher than that of FDA drugs (0.64), with CNP0202879 (0.899) and CNP0383278 (0.848) showing exceptional drug-likeness, outperforming all FDA-approved agents in this dataset. Regarding synthetic accessibility, both groups display similar trends, but CNP0383278 (2.756) and CNP0393067 (2.772) stand out as easier to synthesize than most FDA drugs, being comparable to rilpivirine (2.683), the easiest among the approved drugs. Conversely, CNP0514278 (4.405) and emtricitabine (4.565) present moderate synthetic challenges. Overall, CNP0383278 offers the best balance between high drug-likeness and synthetic feasibility, making it a promising candidate compared to existing FDA-approved drugs.

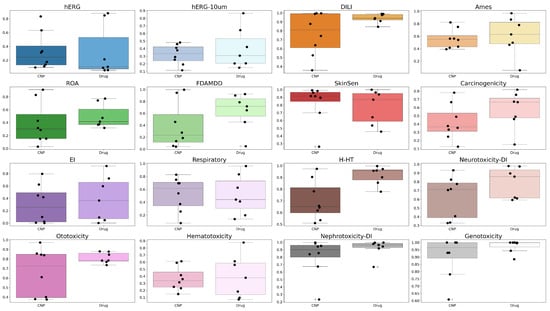

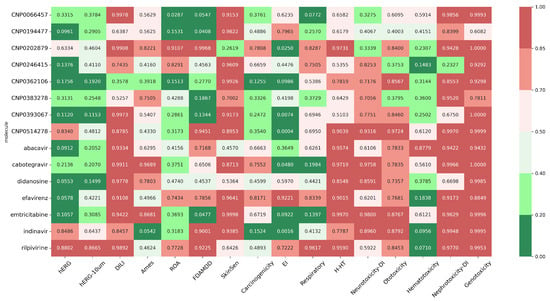

Following the pharmacokinetic analysis, the selected compounds were further characterized from a toxicity perspective using ADMETlab3, enabling the evaluation of potential safety profiles across multiple parameters (Figure 17): hERG Blockers (hERG), hERG Blockers 10 µM (hERG-10 µm), Drug Induced Liver Injury (DILI), AMES Toxicity (Ames), Rat Oral Acute Toxicity (ROA), FDA Maximum Recommended Daily Dose (FDAMDD), Skin Sensitization (SkinSen), Carcinogenicity, Eye Irritation (EI), Respiratory toxicants (Respiratory), Human Hepatotoxicity (H-HT), Drug-induced Neurotoxicity (Neurotoxicity-DI), Ototoxicity, Hematotoxicity, Drug-induced Nephrotoxicity (Nephrotoxicity-DI), and Genotoxicity.

Figure 17.

Comparative analysis of computed toxicity parameters for natural compounds (CNPs) versus approved drugs (abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, rilpivirine).

Predicted toxicity endpoints were evaluated against established ADMETlab 3 thresholds, allowing classification of compounds as low-risk or high-risk for each toxicity parameter (Figure 18). Integrated analysis of toxicity, absorption, solubility, and distribution parameters indicates that CNP0194477 and CNP0393067 are among the most promising natural compounds. Predicted toxicity values are generally lower than those of approved antiretroviral drugs: cardiotoxicity (hERG) is low for CNP0194477 (0.096) and CNP0393067 (0.112) compared to rilpivirine (0.880) and indinavir (0.849), while hepatotoxicity (DILI: 0.638–0.997) and genotoxicity (0.608–0.999) are favorable. Skin sensitization (0.917–0.982) and respiratory toxicity (0.257–0.694) are also lower or comparable to reference drugs. Regarding absorption and distribution, oral absorption (%HOA) is high for CNP0393067 (100%) and CNP0246415 (96%), comparable to efavirenz (100%) and higher than didanosine (66.6%), indicating good permeability potential. In terms of solubility (QPlogS), CNP0194477 (−2.708) and CNP0383278 (−4.875) are more soluble than rilpivirine (−6.860) and indinavir (−5.852), which could facilitate formulation and bioavailability. Efflux and distribution indicators such as QPPCaco are lower for CNP0383278 (27.8) and CNP0194477 (428) compared to efavirenz (1558) and rilpivirine (152), suggesting that, despite promising solubility, some structural optimization may further enhance intestinal permeability.

Figure 18.

Values of toxicity parameters for natural compounds (CNPs) versus approved drugs (abacavir, cabotegravir, didanosine, efavirenz, emtricitabine, indinavir, rilpivirine).

The workflow, which integrates machine learning and deep learning approaches through an automated pipeline, along with 3D shape similarity and ADMET evaluation, proved effective in prioritizing natural compounds with potential multi-target activity against HIV-1 enzymes. The consensus-based approach across multiple models minimized algorithm-specific bias and increased confidence in the predicted actives. The selected natural compounds displayed drug-like physicochemical properties and favorable ADME profiles, supporting their potential for oral bioavailability and reduced toxicity. CNP0194477 and CNP0393067, in particular, emerged as the most promising candidates due to low predicted hERG risk and optimal absorption, highlighting their suitability for further experimental testing. These findings demonstrate that integrating complementary computational strategies can enhance the reliability of virtual screening for natural products. Moreover, the approach allows for efficient identification of candidates with balanced efficacy and safety profiles, potentially accelerating the early stages of anti-HIV drug discovery.

4. Conclusions

The hybrid computational strategy integrating machine learning, 3D shape-based screening, and ADMETox profiling proved highly effective in identifying potential natural HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Among the tested models, Random Forest (RFC) demonstrated the highest predictive performance, with accuracy (ACC) of 0.9759, 0.8370, and 0.8427, F1-score of 0.9830, 0.8858, and 0.8863, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) of 0.9419, 0.6068, and 0.6344 in the training, validation, and testing phases, respectively, followed by KNN (ACC 0.9335, 0.8071, and 0.8043; F1 0.9533, 0.8650, and 0.8598; MCC 0.8387, 0.5310, and 0.5421) and MLP (ACC 0.8943, 0.8133, and 0.8152; F1 0.9250, 0.8660, and 0.8649; MCC 0.7475, 0.5592, and 0.5751). CNN showed moderate performance (ACC 0.8583, 0.7913, and 0.7832; F1 0.8988, 0.8507, and 0.8406; MCC 0.6627, 0.5013, and 0.5031), while SVC displayed lower robustness (ACC 0.8366, 0.7739, and 0.7702; F1 0.8923, 0.8517, and 0.8445; MCC 0.5906, 0.4107, and 0.4446). The best-performing models were applied to the COCONUT database, yielding 4511 compounds predicted as potential actives. After 3D shape similarity filtering, eight top-ranked candidates were prioritized for further evaluation of physicochemical properties, drug-likeness, ADMET characteristics, and synthetic accessibility. Notably, CNP0194477 and CNP0393067 emerged as promising leads, exhibiting low cardiotoxicity (hERG risk: 0.096 and 0.112), favorable hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity profiles, and good predicted oral absorption. These results demonstrate the consistent and robust predictive performance of the RFC, with KNN and MLP offering competitive alternatives, while CNN and SVC show lower stability, particularly in balanced classification, as reflected by the MCC values. Overall, this study presents a hybrid, object-oriented computational pipeline that combines machine learning and deep learning models with structure- and property-based screening, including 3D shape similarity and pharmacokinetic (ADMET) evaluation, to efficiently prioritize natural compounds with potential anti-HIV activity. The proposed framework provides a flexible and interpretable workflow that can be extended to other compound libraries or therapeutic targets. Importantly, the predicted results require experimental validation to confirm antiviral potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13103327/s1, Figure S1: Schematic representation of the 10-fold cross-validation procedure used for model evaluation.

Author Contributions

L.C. conceived the experiment(s), C.-B.C., L.G. and L.C. performed the experiment(s), C.-B.C., L.G. and L.C. analyzed the results, C.-B.C. and L.C. wrote the initial draft, C.-B.C. and L.C. revised, and C.-B.C. and L.C. finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. This work was partially supported by Program no 1, from the “Coriolan Dragulescu” Institute of Chemistry Timisoara, Romania, and by project “ICT-Interdisciplinary Center for Smart Specialization in Chemical Biology (RO-OPENSCREEN)”, MySMIS code: 127952, Contract no. 371/20.07.2020, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fundunder the Competitiveness Operational Program 2014–2020.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank OpenEye Ltd. (Cadence), and BIOVIA software Inc. (Discovery Studio Visualizer) for providing academic license.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| ACC | Accuracy |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| BACC | Balanced Accuracy |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CNP | Natural Compounds |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| donorHB | Number of hydrogen-bond donors |

| F1 | F1-Score |

| FISA | Hydrophilic/polar component of SASA |

| FOSA | Hydrophobic component of SASA |

| G-MEAN | Geometric Mean |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IN | Integrase |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| MACCS | Molecular ACCess System |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| PISA | Aromatic surface area |

| PR | Protease |

| PSA | Polar Surface Area |

| QED | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness |

| QPlogHERG | Predicted inhibition of hERG (human Ether-à-go-go-related) K+ channels |

| QPlogPo/w | Octanol/water partition coefficient (lipophilicity) |

| QPlogS | Aqueous solubility |

| QPPCaco | Caco-2 cell permeability |

| QPPMDCK | Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cell permeability |

| REC | Recall |

| RFC | Random Forest Classifier |

| ROC-AUC | Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under Curve |

| ROCS | Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures |

| RT | Reverse Transcriptase |

| SASA | Total solvent-accessible surface area |

| SP | Specificity |

| SVC | Support Vector Classifier |

| VS | Virtual Screening |

References

- Kang, J.X.; Zhao, G.K.; Yang, X.M.; Huang, M.X.; Hui, W.Q.; Zeng, R.; Ouyang, Q. Recent advances on dual inhibitors targeting HIV reverse transcriptase associated polymerase and ribonuclease H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 250, 115196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levintov, L.; Vashisth, H. Structural and computational studies of HIV-1 RNA. RNA Biol. 2023, 21, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, S.K.; Quraishi, M.; Prabakaran, D.S.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Ramesh, T.; Rajasekharan, S.K.; Raorane, C.J.; Sonawane, T.; Ravichandran, V. Exploring Zinc C295 as a Dual HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitor: From Strand Transfer to 3-Processing Suppression. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, O.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Du, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ge, J.; Hou, T.; et al. Protein–peptide docking with a rational and accurate diffusion generative model. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacureanu, L.; Bora, A.; Crisan, L. New Insights on the Activity and Selectivity of MAO-B Inhibitors through In Silico Methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yu, J.L.; Yang, Z.B.; Chen, Y.T.; Wei, S.Q.; Meng, F.B.; Wang, Y.G.; Huang, X.T.; Li, G.B. Pharmacophore-oriented 3D molecular generation toward efficient feature-customized drug discovery. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, P.C.; Afiukwa, C.A.; Orji, O.U.; Ezeh, E.M.; Ofoke, I.H.; Ogbu, C.O.; Ugwuja, E.I.; Aja, P.M. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, S.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Javan, M.J. In silico study of natural antioxidants. VItamins Horm. 2023, 121, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, L.; Pacureanu, L.; Bora, A.; Avram, S.; Kurunczi, L.; Simon, Z. QSAR study and molecular docking on indirubin inhibitors of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2012, 11, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Azad, I.; Sheikh, S.Y.; Ali, S.N.; Ahmad, N.; Kamal, A.; Faiyyaz, M.; Khan, A.R.; Ahmad, V.; Alghamdi, A.A.; et al. Quantum chemical modeling, molecular docking, and ADMET evaluation of imidazole phenothiazine hybrids. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissouq, A.E.; Bouachrine, M.; Ouammou, A.; Khalil, F. Homology modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking, molecular dynamic (MD) simulation, and ADMET approaches for identification of natural anti-Parkinson agents targeting MAO-B protein. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 786, 136803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, D.; Crisan, L.; Funar-Timofei, S.; Mracec, M. A quantitative structure–activity relationships study for the anti-HIV-1 activities of 1-[(2-hydroxyethoxy)methyl]-6-(phenylthio)thymine derivatives using multiple linear regression and partial least squares methodologies. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2013, 78, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Triterpene esters from Uncaria rhynchophylla hooks as potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors and their molecular docking study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Gu, Q.; Hughes, J.; Robertson, D.L. In silico prediction of HIV-1-host molecular interactions and their directionality. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elalouf, A. In-silico Structural Modeling of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Proteins. Biomed. Eng. Comput. Biol. 2023, 14, 11795972231154402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, L.; Istrate, D. In silico approach for fighting human immunodeficiency virus: A drug repurposing strategy. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, Y.; Wen, X.; Xi, Z. Prediction and molecular field view of drug resistance in HIV-1 protease mutants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbova, E.; Stolbov, L.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V.; Tarasova, O. Quantitative Prediction of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Drug Resistance. Viruses 2024, 16, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.K.; Chen, T.B.; Kouznetsova, V.L.; Tsigelny, I.F. Machine-learning-based virtual screening and ligand docking identify potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Artif. Intell. Chem. 2023, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipanahi, B.; Delong, A.; Weirauch, M.T.; Frey, B.J. Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Ortiz, V. Machine learning and bioinformatics models in the discovery of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors: A review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T.L.; Trinh, T.C.; To, V.T.; Pham, T.A.; Van Nguyen, P.C.; Phan, T.M.; Truong, T.N. Novel machine learning approach toward classification model of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 14506–14513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblard, F.; Patel, D.; Michailidis, E.; Coats, S.J.; Kasthuri, M.; Biteau, N.; Tber, Z.; Ehteshami, M.; Schinazi, R.F. HIV nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 240, 114554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blassel, L.; Tostevin, A.; Villabona-Arenas, C.J.; Peeters, M.; Hué, S.; Gascuel, O.; UK HIV Drug Resistance Database. Using machine learning and big data to explore the drug resistance landscape in HIV. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, D.; He, C.; Zhang, R.; Wan, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, M.; et al. Construction of Machine Learning Models to Predict Changes in Immune Function Using Clinical Monitoring Indices in HIV/AIDS Patients After 9.9-Years of Antiretroviral Therapy in Yunnan, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 867737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, L.P.; Wensing, A.M. Predicting HIV coreceptor usage with sequence analysis. AIDS Rev. 2013, 15, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Koydemir, H.C.; Gorocs, Z.; Tseng, D.; Cortazar, B.; Feng, S.; Chan, R.Y.L.; Burbano, J.; McLeod, E.; Ozcan, A. Rapid imaging, detection and quantification of Giardia lamblia cysts using mobile-phone based fluorescent microscopy and machine learning. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Muldoon, M.; Theiler, J.; Gao, F.; Gupta, R.; Lapedes, A.; Hahn, B.H.; Wolinsky, S.; Bhattacharya, T. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science 2000, 288, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Saleh, K.B.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askr, H.; Elgeldawi, E.; Aboul Ella, H.; Elshaier, Y.A.; Gomaa, M.M.; Hassanien, A.E. Deep learning in drug discovery: An integrative review and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 5975–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uslu, H.; Das, B.; Dagdogen, H.A.; Santur, Y.; Yilmaz, S.; Turkoglu, I.; Das, R. Discovery of new anti-HIV candidate molecules with an AI-based multi-stage system approach using molecular docking and ADME predictions. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2025, 267, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Zhang, L. AI applications in HIV research: Advances and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1541942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyediran, O.K.; Peace-Ofonabasi, O.B.; Ogundemuren, D.A.; Abdulraheem, A.; Azubuike, C.P.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Ilomunaya, M.O. Artificial intelligence in human immunodeficiency virus mutation prediction and drug design: Advancing personalized treatment and prevention. Pharm. Sci. Adv. 2025, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidana, R.L.B.R.; de Almeida Machado, L.; Aes, A.C.R.G. Benchmarking Machine Learning Models for HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor Resistance Prediction: Impact of Data Set Construction and Feature Representation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 10037–10053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskew, M.; Sharpey-Schafer, K.; De Voux, L.; Crompton, T.; Bor, J.; Rennick, M.; Chirowodza, A.; Miot, J.; Molefi, S.; Onaga, C.; et al. Applying machine learning and predictive modeling to retention and viral suppression in South African HIV treatment cohorts. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukerji, S.S.; Petersen, K.J.; Pohl, K.M.; Dastgheyb, R.M.; Fox, H.S.; Bilder, R.M.; Brouillette, M.-J.; Gross, A.L.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.J.; Paul, R.H.; et al. Machine Learning Approaches to Understand Cognitive Phenotypes in People with HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 227, S48–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunc, H.; Sari, M.; Kotil, S. Machine learning aided multiscale modelling of the HIV-1 infection in the presence of NRTI therapy. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisan, L.; Istrate, D.; Bora, A.; Pacureanu, L. Virtual Screening and Drug Repurposing Experiments to Identify Potential Novel Selective MAO-B Inhibitors for Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisan, L.; Bora, A. Small Molecules of Natural Origin as Potential Anti-HIV Agents: A Computational Approach. Life 2021, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Biswas, D.; Hazra, B. Natural products from plants with prospective anti-HIV activity and relevant mechanisms of action. In Bioactive Natural Products; ur Rahman, A., Ed.; Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 66, pp. 225–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zdrazil, B.; Felix, E.; Hunter, F.; Manners, E.J.; Blackshaw, J.; Corbett, S.; de Veij, M.; Ioannidis, H.; Lopez, D.M.; Mosquera, J.F.; et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: A drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1180–D1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.W. PaDEL-descriptor: An open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Bai, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Miao, Y. Review of Image Classification Algorithms Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of Deep Learning: Concepts, CNN Architectures, Challenges, Applications, Future Directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xie, J.; Zhang, D. An Adaptive Offset Activation Function for CNN Image Classification Tasks. Electronics 2022, 11, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.M. Theoretical Understanding of Convolutional Neural Network: Concepts, Architectures, Applications, Future Directions. Computation 2023, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms—A review. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Haque, I.; Lu, H.; Moni, M.A.; Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Ma, H.; Ou, W.; Zeng, S.; Rao, Y.; Yang, H. A generalized mean distance-based k-nearest neighbor classifier. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 115, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wu, H.; Ning, W. Research on intrusion detection model based on improved MLP algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests; Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 45, pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, R.; Ferrisi, S.; Lofaro, D.; Conforti, D. An Overview on the Advancements of Support Vector Machine Models in Healthcare Applications: A Review. Information 2024, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. 2015. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Avram, S.I.; Crisan, L.; Bora, A.; Pacureanu, L.M.; Avram, S.; Kurunczi, L. Retrospective Group Fusion Similarity Search Based on eROCE Evaluation Metric. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, P.C.D.; Skillman, A.G.; Nicholls, A. Comparison of Shape-Matching and Docking as Virtual Screening Tools. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C.; et al. ADMETlab 3.0: An updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; AbdulHameed, M.D.M.; Wallqvist, A. Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks: Strategies That Improve Early Recognition in Similarity-Based Virtual Screening. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisan, L.; Pacureanu, L.; Avram, S.; Bora, A.; Avram, S.; Kurunczi, L. PLS and Shape-Based Similarity Analysis of Maleimides - GSK-3 Inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2014, 29, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, M.A.A.; El-Behairy, M.F.; Abdallah, I.A.; Abdel-Bar, H.M.; Elimam, H.; Mostafa, A.; Moatasim, Y.; Abouzid, K.A.M.; Elshaier, Y.A.M.M. Structure- and Ligand-Based in silico Studies towards the Repurposing of Marine Bioactive Compounds to Target SARS-CoV-2. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Basu, A. Exploring different virtual screening strategies for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 236850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.; Skillman, A.; Warren, G.; Ellingson, B.; Stahl, M. Conformer generation with OMEGA: Algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the Protein Databank and the Cambridge Structural Database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Zhang, K.Y. A pose prediction approach based on ligand 3D shape similarity. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhorst, J.; Nunez, S.; Terpstra, J.W.; Kruse, C.G. Assessment of Scaffold Hopping Efficiency by Use of Molecular Interaction Fingerprints. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3222–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchmore, S.W.; Debe, D.A.; Metz, J.T.; Brown, S.P.; Martin, Y.C.; Hajduk, P.J. Application of Belief Theory to Similarity Data Fusion for Use in Analog Searching and Lead Hopping. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).