Abstract

Highly accurate quantitative detection of heavy metals is crucial for preventing environmental pollution and safeguarding public health. To address the demand for sensitive and specific detection of Cu2+ ions, we have developed carbon dots using a simple hydrothermal process. The synthesized carbon dots are highly stable in aqueous media, environmentally friendly, and exhibit strong blue photoluminescence at 440 nm when excited at 352 nm, with a quantum yield of 5.73%. Additionally, the size distribution of the carbon dots ranges from 2.0 to 20 nm, and they feature excitation-dependent emission. They retain consistent optical properties across a wide pH range and under high ionic strength. The photoluminescent probes are selectively quenched by Cu2+ ions, with no interference observed from other metal cations such as Ag+, Ca2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, K+, Mg2+, Sn2+, Pb2+, Sr2+, and Zn2+. The emission of carbon dots exhibits a strong linear correlation with Cu2+ concentration in the range of 0–14 μM via a static quenching mechanism, with a detection limit (LOD) of 4.77 μM in water. The proposed carbon dot sensor is low cost and has been successfully tested for detecting Cu2+ ions in general water samples collected from rivers in Taiwan.

1. Introduction

The intake of toxic contaminants and pollutants into the human body has been a long-standing public health issue. This can occur through various means such as drinking water, food consumption, or absorption through the skin and respiratory system. One particularly problematic source of pollution is metal contamination, which can arise from both natural sources and human activities [1,2,3]. High levels of heavy metal ions in drinking water pose a significant threat to individual health. Exposure to metals such as copper and lead can have detrimental effects on various organs, including the bones, kidneys, neurological system, and central nervous system [1,2,3,4]. Of particular concern is the physiological impact of copper ion (Cu2+), which can cause heavy metal poisoning when entering the bloodstream. Excessive levels of copper can cause protein denaturation in the body and damage red blood cells, resulting in hemolysis and anemia [4,5]. While copper is an essential element for living beings, exposure to high levels can cause gastrointestinal disturbances and long-term damage to liver and kidneys. Furthermore, exposure to copper ions has been linked to neurological conditions such as spongiform encephalopathy, Wilson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease [5,6,7,8]. To address this issue, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has set a permissible safe limit of 1.3 ppm for copper ions in drinking water [2,9]. Traditional optical sensors based on metal-based quantum dots suffer from long preparation times and toxicity concerns. Therefore, there is a need for the development of green precursor-derived sensors for simple, rapid, and accurate metal ion detection.

Various methods have been developed for detecting heavy metal ions, including atomic absorption spectrometry, mass spectrometry, electrochemical techniques, and X-ray fluorescence spectrometry; however, these methods are often costly and require lengthy samples processing [10,11,12]. On the other hand, fluorescence sensors offer an environmentally friendly and efficient solution for detecting metal ions with rapid response times, high selectivity and sensitivities, low cost, and simple operation [12,13]. Given the importance of heavy metal ion detection in biological and environmental processes, the development of fluorescent sensors that can distinguish between different analytes remains a challenging task [14].

Fluorescent carbon dots (C-dots) have garnered significant attention in research due to their wide range of applications, unique optical properties, biocompatibility, low toxicity, solubility in water, high stability, and other exceptional features [15,16,17]. To date, C-dots have been used for sensors [15,18], bioimaging [19,20], electrocatalysis [21,22], photocatalysis [21,22,23], drug delivery [20,24,25], and in optoelectronic applications [24,26]. The synthesis of C-dots can be achieved through top-down or bottom-up methods, with the latter offering more control over optical properties, higher yields, and improved carbonation [17,27]. The sizes, compositions, and crosslinking-enhanced emission effects of C-dots are the three key parameters that influence their optical and electrical properties [17,18,22,27]. During the initial polymerization stage of C-dots, the fluorescence emission mechanism is mainly associated with the molecular state of the preliminary polymers. As the C-dot polymer structures develop, crosslinking-enhanced emission effects start to dominate, and carbon nuclei gradually appear with the increasing degree of carbonization. This process leads to the formation of a carbon core, resulting in a core–shell structure. Simultaneously, the fluorescence emission mechanism shifts to rely on the carbon nucleus, particle size, and surface states. Importantly, the surface state is determined by the hybridization of the carbon skeleton with its attached chemical groups, rather than by isolated side chains or functional groups. The size effect will eventually become predominant once complete carbonization is achieved with surface functional groups and side chains disappear [17,18,22,27]. To modify these characteristics, functionalization techniques such as surface modification or intrinsic heteroatom doping can be employed [22,24,27]. However, the stability of C-dots remains a challenge in many applications, although post-surface treatments have shown promise in addressing this issue. Notably, C-dots have been successfully utilized as fluorescence probes for the detection of metal ions [28].

While organic ligands and other C-dot probes exist, our study targets specific limitations regarding green synthesis and stability that previous methods often lack. In this study, we successfully synthesized carbohydrate-functionalized carbon dots (C-dots) using a simple one-pot hydrothermal method. The resulting C-dots exhibited bright blue fluorescence with a quantum yield of 5.73% and demonstrated efficient photoluminescence (PL) quenching upon exposure to Cu2+ ions in aqueous solution at physiological pH (~7.4). Notably, the C-dots displayed high selectivity toward Cu2+ over other transition metal ions, attributed to the stronger binding affinity and faster chelation kinetics of Cu2+ at the C-dot surface. This selective quenching behavior underscores the potential of these C-dots as a sensitive and straightforward fluorescent probe for Cu2+ detection in aqueous environments. Moreover, their low toxicity highlights their suitability for broader applications in biosensing and environmental monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

NaOH, HCl, Na2HPO4, NaH2PO4, potassium phosphate, Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris-HCl), and NaHCO3, Quinine hemisulfate salt monohydrate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Metal ions (Ag+, Ca2+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, K+, Mg2+, Sn2+, Pb2+, Sr2+ and Zn2+) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Dialysis membrane Pre-treated RC Tubing MWCO: 1 KD (vol/length: 4.6 mL/cm) was purchased from Spectrum Laboratories, Inc. (Rancho Dominguez, Carson, CA, USA). All reagents were of analytical grade or higher and used as received without further treatment.

2.2. Apparatus

Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopic analyses were performed using the Jasco V-530 (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan); the absorbance spectra were recorded in the wavelength of 200–800 nm with 1.0 cm quartz cells. Infrared (IR) spectra were collected with an Alpha IR Spectrophotometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany), and spectra were recorded within the range of 1000–4500 cm−1. Fluorescence spectra were scanned using a F-2500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescence lifetime decays were acquired using a Quantaurus-Tau fluorescence lifetime Spectrofluormeter FS5 (Edinburgh Instruments, Livingston, UK).

The molecular structures of the synthesized C-dots were analyzed using a Bruker Optics FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany), collecting spectra over the range of 600–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 2 cm−1. TEM images were obtained using an HT 7700 TEM (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV for morphological investigation. The elemental content and bonding types were characterized using an Escalab 250 X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a mono X-ray source Al Kα excitation (0.5 eV, Ag 3d5/2). XRD patterns were recorded using a Bruker-D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation (30 kV, 10 mA, and 2 theta).

2.3. Synthesis and Purification of Luminescent C-Dots

Luminescent carbon dots were synthesized via a single-step hydrothermal approach, as previously described [29]. Briefly, a mixture of 8.0 g of Tris and 0.5 g of lactose were dissolved in 160 mL of deionized water in a round-bottom flask. The solution was adjusted to pH 10.5 and subjected to hydrothermal reflux at 100 °C for 8 h under continuous stirring. Carbonization was observed when the color appeared to be yellow. The resulting hot solution was then cooled and maintained at 25 °C for 3 days to ensure complete reaction. Following synthesis, the pH was adjusted to neutral using hydrochloric acid (HCl), and the solution was purified via dialysis against deionized water for 11 h using pre-treated regenerated cellulose tubing (MWCO 1 kDa, 65 mL capacity). The purification process was monitored using fluorescence spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Further purification details are available in reference [29]. To quantify the yield, an aliquot of the purified dispersion was dried in an oven at 65 °C overnight to remove residual solvent, and the resulting dry mass was recorded.

2.4. Stability Studies of C-Dots

The stability of the synthesized carbon dots was evaluated under varying pH conditions, ionic strengths, and continuous UV irradiation [29]. The pH stability of carbon dots can be assessed by adjusting the solution to pH values ranging from 2.0 to 12.0 using HCl or sodium hydroxide (NaOH); the fluorescence response of the C-dots was measured after a 10 min equilibration period. To examine the influence of ionic strength, a 5 mL aliquot of C-dot solution was mixed with potassium chloride (KCl) solutions of 0.2 M, 0.4 M, 0.6 M, 0.8 M, and 1.0 M in centrifuge tubes and incubated for 10 min. The resulting mixtures were then subjected to photoluminescence measurements, with excitation at 352 nm. Photostability was evaluated by exposing the C-dot solution to UV light at 365 nm for 180 min. Aliquots of 1 mL were withdrawn for measurement of UV–Vis absorption and photoluminescence intensity every 15 min. This process was repeated throughout the exposure period to monitor temporal changes in the optical properties of the C-dots.

2.5. Optical, Structural, and Morphological Characterization of C-Dots

Absorption characteristics are commonly analyzed to identify electronic transition bands using UV–visible absorbance spectroscopy [30]. In the context of optical sensing in C-dots, PL emission and excitation spectra are measured using a fluorescence spectrometer, serving as fundamental parameters [30,31]. The absolute or relative quantum yield is determined by either utilizing an integrating sphere or comparing the fluorescence intensity with a reference sample of known quantum yield. Here, quinine hemisulfate is employed as the reference to determine C-dots’ quantum yield; the details for calculation of quantum yield can be found in the Supplementary Materials section [32]. To investigate the fluorescence dynamics, PL lifetime spectroscopy is employed to measure the lifetime of the emitted light [33]. The size of the C-dots was initially measured using particle size analyzers based on dynamic light scattering. This technique involves analyzing the fluctuations caused by the Brownian motion of nanoparticles scattering laser light. Furthermore, zeta potential studies provide information about the surface charge of carbon dots [34].

The dried purified carbon dots were further analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques.

2.6. Copper and Other Metal Ion Detection of C-Dots

The selectivity of C-dots toward a variety of metal ions—including Ag+, Ca2+, Cr2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, K+, Mg2+, Sn2+, Pb2+, Sr2+, and Zn2+—was systematically investigated. In each test, 350 μL of a 20 μM metal ion solution was mixed with 300 μL of C-dot solution (0.1 μg/mL), and double-distilled water was added to bring the total volume to 1 mL. The mixtures were incubated for 10 min, followed by photoluminescence measurements under 352 nm excitation. To assess potential interference from other metal ions on Cu2+ detection, the above protocol was repeated with an additional 350 μL of Cu2+ solution (20 μM) added to the metal/C-dot mixtures. These samples were transferred to a 3 mL quartz cuvette, incubated for 10 min, and then measured for PL intensity. For quantifying the quenching response of C-dots to Cu2+, a series of solutions with varying Cu2+ concentrations (0–14 μM) were prepared under the same conditions. After a 10 min incubation period at room temperature, PL spectra were recorded. Both excitation and emission slit widths were set to 5 nm.

2.7. Quenching Data and Job’s Plot Analysis

The quenching of fluorescence by metal ions [M(II)] is described using the Stern–Volmer equation:

where I0 is the fluorescence intensity without metal ions, I is the fluorescence intensity observed in the presence of a metal ion, and Ksv is the static Stern–Volmer constant [35,36]. The average fluorescence lifetime of C-dots was measured via a time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) time-resolved Quantaurus–Tau fluorescence lifetime Spectrofluormeter FS5, calculated using the following formula:

I0/I = 1 + Ksv[M(II)]

τ1, τ2, and τ3 represent the time-resolved decay lifetimes, while A1, A2, and A3 denote their corresponding contribution fractions.

To investigate the stoichiometric interaction between C-dots and Cu2+, Job’s plot analysis was performed by systematically varying the molar ratio of Cu2+ to C-dots while keeping the total volume constant at 1 mL. A combined solution of C-dots and Cu2+ was prepared. The concentration of Cu2+ was varied from 164.6 to 303.4 ppm, while the corresponding C-dot concentration ranged from 244.7 to 21.4 ppm. One example ratio used was 0.3:0.7 for C-dots (120.3 ppm) to Cu2+ (280.8 ppm). In a separate experiment, another concentration range was tested, with Cu2+ from 29.5 to 19.8 ppm and C-dots from 244.7 to 21.4 ppm. In this case, a representative ratio was 0.7:0.3 for C-dots (62.8 ppm) and Cu2+ (26.9 ppm). These experiments enabled determination of the stoichiometric ratio between C-dots and Cu2+ using Job’s method.

2.8. Copper Ion Detection of C-Dots in Water and Real Sample Detection

To ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the experiments, the detection of Cu2+ ions was carried out in double-distilled water. Initially, the detection feasibility was confirmed by measuring fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength of 352 nm in several scenarios: pure double-distilled water, C-dots dispersed in double-distilled water, and a solution containing 15 μM Cu2+ ions in double-distilled water. Additionally, the time-dependent fluorescence quenching of C-dots upon the addition of Cu2+ ions was investigated to establish equilibrium in double-distilled water. The impact of varying concentrations of Cu2+ ions on the fluorescence performance of C-dots was assessed by measuring fluorescence intensity across different Cu2+ ion concentration solutions. Furthermore, a defined metal mixture sample containing 6 μM of Cu2+ plus 3 μM of Zn2+, Ni2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ each was tested to evaluate metal ion interference. For the real water sample collected in fields, 650 μL of each sample was combined with 300 μL of carbon dots (38.4 μg/L) and spiked with 50 μL of an internal standard copper solution containing 480 μM copper sulphate. Each experiment was performed in triplicate to minimize error and obtain an average value.

3. Results and Discussion

The carbon dots were characterized using both conventional/basic techniques as well as a few advanced methods, which are essential benchmarks for identifying the properties of the C-dots and their capability for detecting heavy metal ions.

3.1. Optical Properties of C-Dots

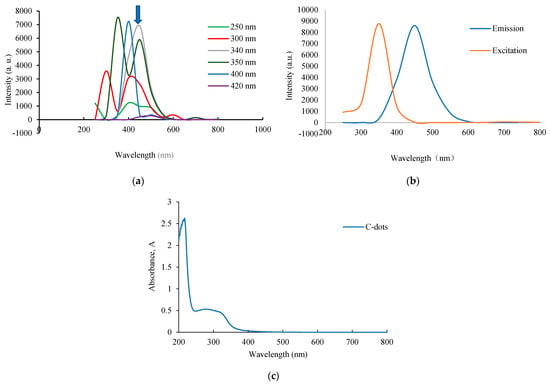

The optical properties of C-dots were characterized in terms of the fluorescence and UV–vis spectra. Figure 1a illustrates a stable emission wavelength behavior in the fluorescence emission spectra of C-dots across different excitation wavelengths ranging from 250 to 420 nm. The emission peaks of C-dots shifted with different excitation wavelengths, yet the maximum emission wavelength remained consistent at around 440 nm. This excitation-independent emission property distinguishes these C-dots from many previously reported types, potentially minimizing autofluorescence in practical applications [37,38]. This characteristic is attributed to the uniform particle size distribution and localized surface state band structure of the C-dots [39]. As shown in Figure 1b, the maximum emission wavelength of C-dots was located at 440 nm at an excitation wavelength of 352 nm. In aqueous solution, C-dots exhibited a UV absorption peak at 256 nm, as shown in Figure 1c, corresponding to π–π transitions of C=C bonds and n–π transitions of C-OH groups [27]. The quantum yield of the synthesized C-dots was approximately 5.73%, as determined using quinine hemisulfate (quantum yield ~54%) as the reference standard (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

(a) Photoluminescence spectra of C-dots recorded under excitation wavelengths ranging from 250 to 420 nm. The arrow indicates the emission around 440 nm. (b) Excitation and emission spectra of the C-dots. (c) UV–vis absorption spectra of C-dot solutions.

3.2. Photoluminescence Stability Studies of C-Dots

A series of experiments were conducted to evaluate the stability of the synthesized C-dots under a range of environmental conditions. Parameters including storage time, temperature, pH, ionic strength, and UV irradiation duration were systematically investigated. These assessments are essential, as the C-dots are intended for applications that may require stability under extreme or fluctuating conditions, such as high salinity or acidic/basic environments. Notably, robust photostability is a key prerequisite for their long-term use and potential commercialization in optoelectronic and bioimaging applications.

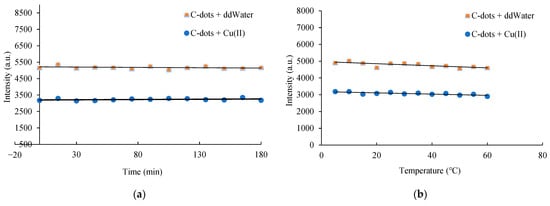

3.2.1. Effects of Time, Temperature, and pH

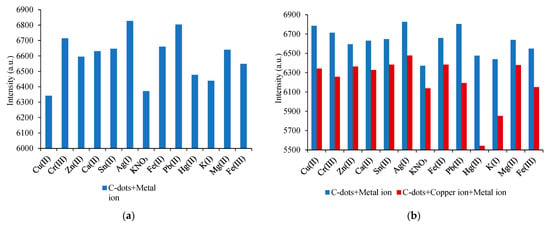

The synthesized C-dots exhibited stable fluorescence emission over a 3 h period, with no significant loss in photoluminescence intensity observed (Figure 2a). Temperature variations between 20 °C and 60 °C did not significantly affect the emission intensity, indicating good thermal stability (Figure 2b). The initial pH of the precursor solution played a critical role in C-dot formation. The pH sensitivity of the C-dots arises from the protonation and deprotonation of surface oxygen-containing functional groups, which influence the electronic energy levels [40]. Alkaline conditions were found to be more favourable for the synthesis process, with optimal fluorescence intensity obtained at an initial pH of 10.5 (Figure 2c). This pH value was naturally maintained due to the ionization of Tris, eliminating the need for external pH adjustment. C-dots demonstrated moderate pH sensitivity, retaining stable optical properties across a broad pH range of 3.0 to 9.0. However, under strongly alkaline conditions (pH > 11.0), a reduction in photoluminescence intensity was observed, potentially due to the formation of hydrogen bonds involving surface hydroxyl groups. These interactions may interfere with electron–hole recombination and disrupt radiative transitions, therefore causing fluorescence quenching [41].

Figure 2.

Effects of (a) reaction time, (b) temperature, (c) pH, (d) ionic strength, and (e) exposure duration on the stability of C-dots and C-dots complexed with Cu(II). All samples were incubated for 10 min, and their photoluminescence spectra were recorded under 352 nm excitation.

3.2.2. Effects of Ionic Strength and Exposure Duration

At low ionic strength, carbon dots (C-dots) bearing charged surface functional groups exhibit strong electrostatic repulsion, promoting colloidal stability. However, at elevated ionic strengths, electrostatic interactions are screened by surrounding ions, potentially leading to nanoparticle aggregation and altered physicochemical properties. To assess the ionic tolerance of the synthesized C-dots, their fluorescence behavior was evaluated under increasing concentrations of KCl (0.1–0.4 M). As shown in Figure 2d, no significant change in fluorescence intensity was observed, indicating stable optical properties under moderate ionic stress. Notably, even at KCl concentrations as high as 1.0 M, no visible precipitation occurred, suggesting excellent colloidal stability and resistance to salt-induced aggregation [29]. These results demonstrate the robustness of carbohydrate-derived C-dots under physiologically relevant ionic conditions, supporting their utility in chemical and biochemical applications. In addition, the long-term storage stability of the C-dots was confirmed, with no significant decline in photoluminescence intensity observed after one year at room temperature. Photostability was further assessed under continuous UV irradiation (365 nm) over a 180 min period. As shown in Figure 2e, after prolonged irradiation, the photoluminescence intensity retained ~85% of its initial value, demonstrating excellent resistance to photobleaching and strong potential for use in long-term fluorescence-based assays and imaging applications.

3.3. C-Dots as a Photoluminescent Probe for Heavy Metal Cu2+ Ions Detection

Certain heavy metal ions, including copper, iron, aluminium, and trivalent chromium, are essential micronutrients for biological systems; however, at elevated concentrations, they can exhibit significant toxicity [1,2,3,4]. In contrast, trace levels of non-essential heavy metals such as hexavalent chromium, lead(II), arsenic(III), cadmium(II), and mercury(II) are among the most persistent and hazardous pollutants in industrial wastewater due to their non-biodegradable nature and high toxicity [3,5]. The development of environmentally benign and practically deployable sensors for the detection of such metal ions is therefore imperative for early intervention and mitigation of water contamination. While conventional detection platforms based on metal nanoparticles and organic dyes are gradually being phased out due to their instability and potential toxicity, fluorescent carbon dots have emerged as promising alternatives. Owing to their excellent photostability, tuneable surface chemistry, and biocompatibility, C-dots are increasingly being explored for real-time, sensitive, and selective detection of heavy metal ions in both environmental and biological contexts [12,13,14].

3.3.1. Selectivity and Sensitivity of the C-Dots

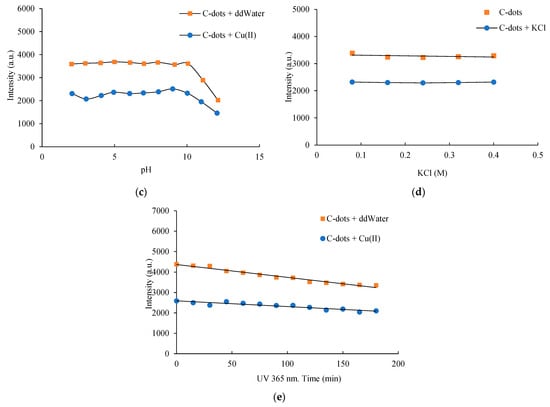

To evaluate the selectivity and sensing performance of the synthesized carbon dots, fluorescence interference experiments were conducted using 11 common metal ions. As shown in Figure 3a, the fluorescence intensities of C-dots were monitored upon exposure to various individual and combined ion solutions. For specificity analysis, the fluorescence response of the C-dot–Cu2+ system was examined in the presence of potentially interfering metal ions, all maintained at a fixed concentration of 7.0 μM. As illustrated in Figure 3b, none of the tested ions significantly altered the Cu2+-induced photoluminescence quenching, suggesting negligible competitive binding and confirming the high selectivity of C-dots toward Cu2+ ions in aqueous media. The strong affinity between Cu2+ and surface functional groups on the C-dots facilitates selective chelation, enabling the C-dots to function effectively as a “turn-off” fluorescent probe for Cu2+ detection. This selective quenching behavior is attributed to specific coordination interactions between Cu2+ ions and oxygen-containing groups on the C-dot surface, which promote efficient energy transfer and suppress PL emission. Such interactions are modulated by the surface chemistry, electronic trap states, particle size, and edge morphology of the C-dots [12,13,14,15]. These findings support the potential of C-dots as highly selective and sensitive chemosensors for copper ion detection, with promising applicability in environmental and biological monitoring.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of interference from various metal cations in the C-dot sensing system. (a) Histogram of photoluminescence intensity at 440 nm for C-dots in deionized water in the presence of different metal ions (excitation at 352 nm). (b) Comparison of photoluminescence intensity at 440 nm with and without additional Cu(II) ions. Red bars indicate the presence of Cu(II), while blue bars represent samples without Cu(II).

3.3.2. Characterization of C-Dots Interacting with Copper Ions

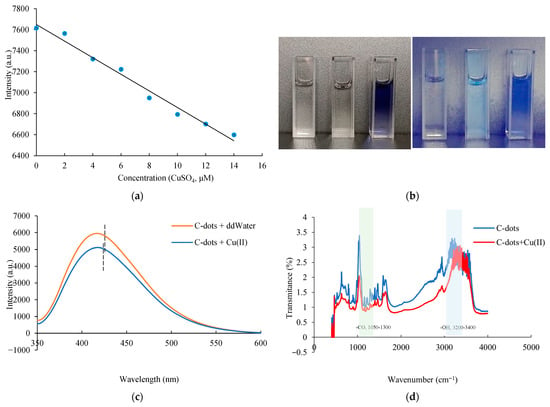

In this study, the synthesized carbon dots were applied as fluorescent probes for the detection of Cu2+ ions based on their fluorescence quenching effect. The photoluminescence spectra were recorded upon incremental addition of Cu2+ ions (0–14 μM), revealing a progressive decrease in emission intensity with increasing concentration (Figure 4a). This concentration-dependent quenching demonstrated a strong quantitative relationship, with a calculated limit of detection (LOD) of 4.77 μM—well below the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) threshold of 20 μM for copper in drinking water. Notably, the C-dot solution changed visibly from brown to blue under natural light, and it exhibited bright blue fluorescence under 365 nm UV irradiation (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Photoluminescence-based detection of Cu(II) using C-dots. (a) A linear correlation between the fluorescence intensity at 440 nm and Cu(II) concentrations ranging from 0 to 14 µM. (b) Visual observation of C-dot solutions: under white light (left), the solution appears brown; under UV light at 365 nm (right), the C-dot solution emits bright blue fluorescence (left: ddH2O; middle: C-dots; right: C-dots + Cu(II)). (c) PL spectra comparison before and after Cu(II) addition: C-dots and C-dots + Cu(II) (red). (d) FT-IR spectra of C-dots and C-dots + Cu(II) (red), showing changes upon Cu(II) interaction. (e) Stern–Volmer plot of C-dots with Cu(II) at concentrations ranging from 0 to 40 µM; the fluorescence wavelength is 440 nm for C-dots. (f) Fluorescence decay curve (475 nm) before and after the addition of Cu(II) to C-dots. (g) Stern–Volmer plot of C-dots with Cu(II) at concentrations ranging from 2 to 4.8 mM; the fluorescence wavelength is 440 nm for C-dots. (h) Job’s plot analysis at high Cu(II)/C-dot ratios indicates a binding stoichiometry of approximately 2.53:1 (Cu2+:C-dots). (i) At lower Cu(II)/C-dot ratios (<1.5), the binding stoichiometry shifts to approximately 1:2.5, suggesting a concentration-dependent interaction behavior.

To elucidate the quenching mechanism, fluorescence spectra revealed quenching events in the emission peak from 442–470 nm to 430–459 nm upon Cu2+ addition (Figure 4c), suggesting complexation between Cu2+ and surface functional groups (e.g., –OH, –NH2). Supporting this, FTIR spectra (Figure 4d) showed a reduction in the C–OH peak at 1433 cm−1 and the disappearance of the –OH peak at 3315 cm−1, further indicating coordination interactions. These spectroscopic results suggest that both static and dynamic quenching processes may be involved.

A Stern–Volmer plot was employed to evaluate the fluorescence quenching behavior. A linear Stern–Volmer relationship typically indicates either static or dynamic quenching, while curvature in the plot may suggest a combination of both mechanisms [42]. In this study, the quenching followed the Stern–Volmer equation, as described in Section 2.7 [43]. The Stern–Volmer plot exhibited a linear relationship at lower Cu2+ concentrations (0–40 μM), with a slope of approximately 3.7 × 103 M−1 (Figure 4e). If interpreted as dynamic quenching, the quenching constant kq would be 5.3 × 1012 M−1 s−1, based on Ksv = kq × τ0, where τ0 = 0.7 ns (Figure 4f and Supplementary Figure S3). However, this value is more than two orders of magnitude higher than the diffusion-controlled limit (kdiff ~ 2 × 1010 M−1 s−1), suggesting that the quenching is primarily static. In this case, the slope Ksv represents the association constant between C-dot–Cu2+ aggregates and Cu2+ ions. While the quenching remains linear at lower Cu2+ concentrations, the efficiency increases exponentially at higher concentrations. This indicates that, at low concentrations, quenching mainly occurs through static interactions via C-dot–Cu2+ complex formation, facilitating a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) process. As the Cu2+ concentration increases further to the millimolar range, the Stern–Volmer plot displays upward curvature (Figure 4g), implying that both static and dynamic quenching mechanisms act simultaneously, thereby enhancing the overall quenching efficiency [44].

To investigate the binding stoichiometry between Cu2+ ions and C-dots, Job’s plot analysis was conducted [45]. At Cu2+:C-dot ratios greater than 1.5, a binding stoichiometry of approximately 2.53:1 was observed (Figure 4h). When the ratio dropped below 1.5, the stoichiometry shifted to approximately 1:2.5 (Figure 4i). The shift in stoichiometry is likely driven by the availability of surface functional groups relative to the metal ion concentration. At low Cu2+ concentrations (C-dots in excess), multiple functional groups on the C-dot surface (such as hydroxyl and amino groups) may coordinate with a single copper ion, or a single C-dot may chelate multiple dispersed Cu2+ ions independently, leading to a stoichiometry favouring C-dots (1:2.5). Conversely, at high Cu2+ concentrations (Cu2+ in excess), the surface sites become saturated, and copper ions may induce bridging between C-dots or form clusters on the surface, shifting the apparent stoichiometry (2.5:1).

Earlier studies showed that prepared C-dots contain numerous active functional groups that can bind to target analytes in a variety of ways and cause dynamic or static quenching, electron transfer, the inner filter effect, or photoinduced electron transfer [46]. In this study, the quenching of C-dot fluorescence by Cu2+ is concentration-dependent. At lower Cu2+ concentrations, quenching primarily arises from a static coordination mechanism, where Cu2+ ions form ground-state complexes with surface –OH and –NH2 groups on the C-dots. As the Cu2+ concentration increases, additional dynamic quenching and collisional interactions become significant, further reducing fluorescence intensity. The paramagnetic nature of Cu2+ (d9 configuration) facilitates non-radiative energy dissipation through enhanced spin–orbit coupling (SOC) and metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT), promoting electron–hole recombination and suppressing radiative decay [47,48]. Collectively, these processes account for the observed concentration-dependent quenching behavior, consistent with both static coordination and SOC-assisted pathways.

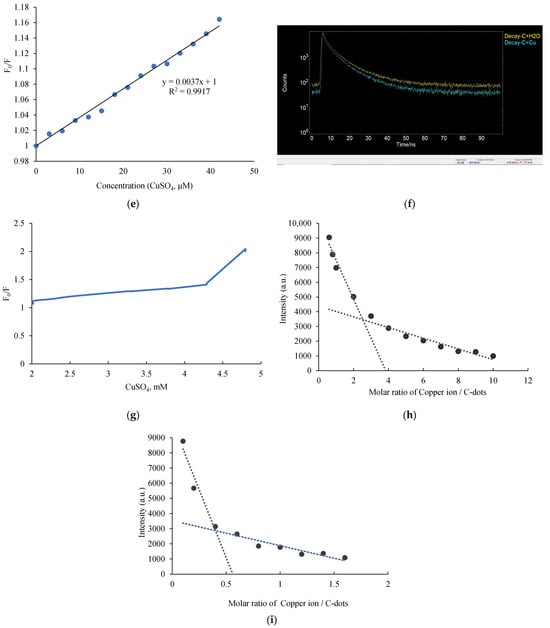

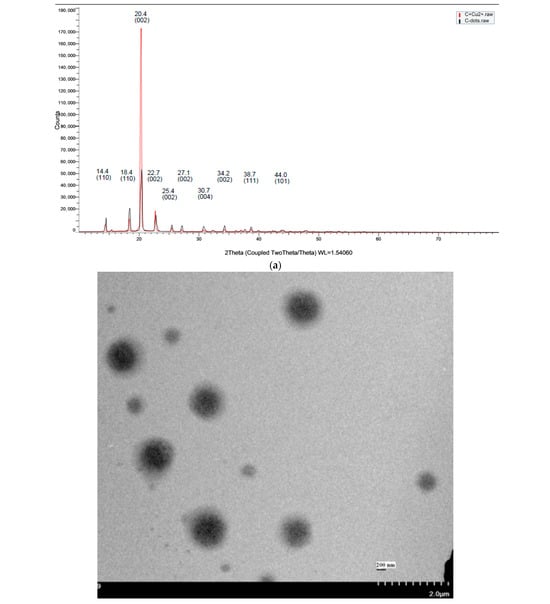

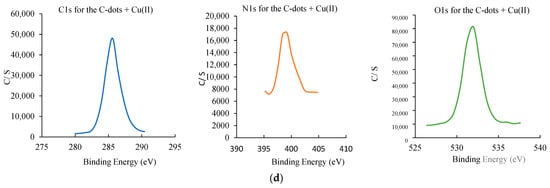

3.4. Structural and Morphological Analysis of C-Dots

The crystallinity of the C-dots on their own and C-dots plus Cu2+ ion can be characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) (Figure 4d) and an X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (Figure 5a). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 5b), Dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 5c), and X-ray photoelectron (XPS) (Figure 5d) experiments were performed to analyze C-dots’ chemical and structural composition. Apart from potential complexation with the addition of Cu2+ ions observed in FT-IR spectra, we also recorded signals corresponding to -C-C-, -C-H, -NH2, and -OH bonds present in the C-dots. Signals corresponding to O–H (3200 cm−1) and N–H (3300–3500 cm−1), C–H (2850–2970 cm−1), C–O (1050–1300 cm−1), C=C (1610–1680 cm−1), C–N (1180–1360 cm−1), and C–O (1214 cm−1), with peaks of C–O (1003 cm−1) and C=C (1600 cm−1), were observed (Figure 4d) [49]. The results show that the surface of C-dots was enriched with hydroxyl and amino groups that support the water solubility of the sample.

Figure 5.

Structural and surface characterization of C-dots and C-dots + Cu(II). (a) XRD patterns of C-dots and C-dots + Cu(II), displaying characteristic Bragg reflections. (b) TEM image showing that C-dots + Cu(II) form spherical aggregates. (c) DLS particle size distribution of C-dots (left) and C-dots + Cu(II) (right), indicating size changes upon Cu(II) binding. (d) XPS analysis: full spectrum of C-dots (top), overlaid spectra of C-dots and C-dots + Cu(II); high-resolution spectra of C 1s (left), N 1s (middle), and O 1s (right) for the C-dot + Cu(II) sample.

Figure 5a represents the XRD patterns of C-dots. XRD revealed the crystallinity of C-dots formed from C domains surrounded with an amorphous carbon network [50]. The C-dots in this study exhibited a primary diffraction peak centered at 2θ = 20.4°, corresponding to the (002) plane. Additionally, other peaks centered at 14.4°, 18.4°, 22.7°, 25.4°, 27.1°, 30.7°, 34.2°, 38.7°, and 44.0° were identified as the (110), (110), (002), (002), (002), (004), (002), (111), and (101) reflections of C-dots, while a peak at 79.9° could not be identified. Peaks attributed to the (100) and (101) planes represented a higher number of oxygen-containing groups, as found in earlier studies [51,52,53]. C-dots showing several distinctive peaks indicate a polycrystalline structure (Figure 5a) [54]. C-dots are often amorphous, and this type of C-dots with polycrystalline organization is not common in the literature [55]. The XRD peak shape indicates that the C-dots exhibit a crystalline structure with an average grain size (D) ranging from 2 to 20 nm, calculated using Scherrer’s formula [55]. The C-dot–Cu2+ composite pattern shows the characteristic peak (002) shifted to 2θ = 20.02°. In addition, the intensity of all diffraction peaks either increased or decreased after the interaction with the Cu2+ due to the increase of the inter-planar distance (002), possibly due to Cu2+ trapped by C-dot sheets.

TEM was employed to examine the structural and morphological features of the synthesized carbon dots and their complexes with Cu2+ ions. TEM analysis revealed uniformly dispersed, spherical nanoparticles with diameters ranging from 2 to 20 nm, indicating the presence of abundant sp2 and sp3 defects in the carbon-based structure (Figure 5b), which aligns with observations from XRD analysis. The TEM images also displayed clear interplanar lattice fringes, indicating an ordered crystalline structure. These lattice fringes corresponded to the (002) crystallographic planes of carbon, supporting the interpretation that the C-dots possess good crystallinity. This conclusion is further reinforced by the sharp and intense XRD peak observed at 2θ ≈ 20.4°, consistent with the graphitic carbon (002) reflection [29].

DLS was used to estimate the average size of the samples. It was observed that interactions during sample handling could result in larger average sizes compared to those measured using TEM. This difference arises because DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter, which includes the solvation shell and surface functional groups in the hydrated state, whereas TEM determines the size of the dry, solid core. Additionally, DLS is an intensity-based measurement that is highly sensitive to larger particles or small aggregates, contributing to the larger observed size values compared to the number-based TEM measurements. The DLS analysis (Figure 5c) revealed that the average particle size increased upon coordination with Cu2+, expanding from a range of 2–20 nm for the original C-dots to 2–80 nm for the Cu2+-coordinated C-dots.

XPS analysis was conducted to further investigate the surface elemental composition and functional groups of C-dots (Figure 5d). The XPS full-scan spectra revealed peaks corresponding to carbon (285.60 eV), nitrogen (399.20 eV), and oxygen (532.0 eV), consistent with FT-IR findings [56]. The atomic percentages of C, N, and O were determined as 17.5%, 1.5%, and 81%, respectively. In the detailed XPS spectra shown in Figure 5d, the C1s peaks observed at 284.48, 285.25, 286.27, and 288.44 eV were attributed to carbon in forms such as C–C, C–N, and C–O bonds [57]. The N1s spectrum displayed peaks at 399.27, 400.57, and 401.82 eV, corresponding to C–N–C and N–H functionalities [57]. The O 1s spectrum exhibited distinct peaks at 531.23 and 533.05 eV, indicative of C–O and C–O–H/C–O–C groups [57].

Based on these findings, C-dots derived from tris-base were successfully synthesized, retaining properties and functional groups with oxygen and nitrogen residues from the tris-base, thereby imparting excellent water solubility.

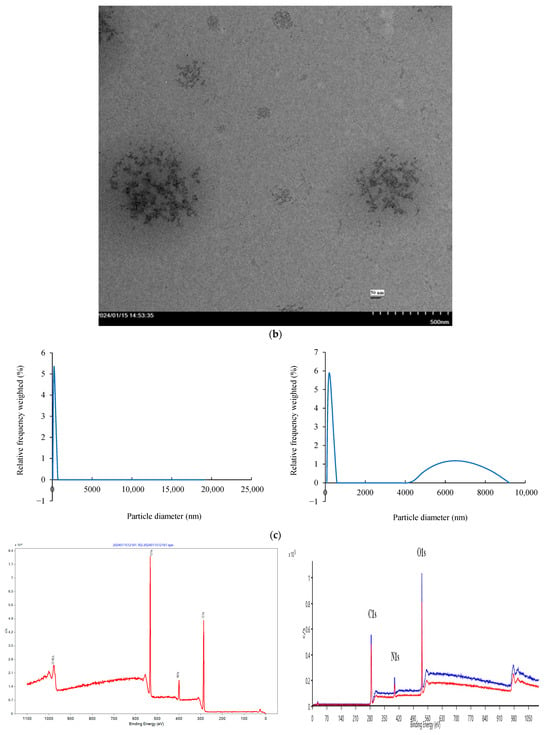

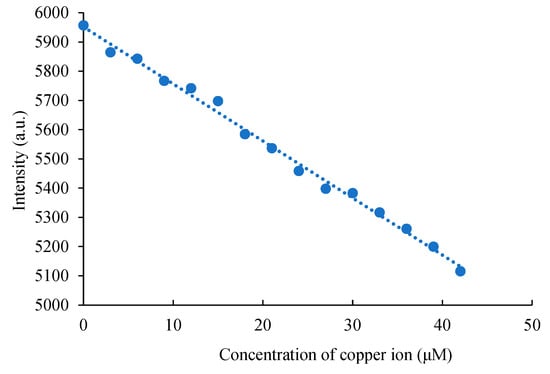

3.5. Detection of Copper Ions in Real Samples

Previously, Liu et al. utilized carbon dots for the detection of Cu2+ ion in river water, demonstrating their effectiveness in environmental water quality analysis [58]. Das et al. prepared nitrogen-doped carbon dots using lemon juice and L-arginine to detect Cu2+ ion in river water [59]. More recently, Pizzoferrato et al. generated nitrogen and sulphur co-doped carbon dots using o-phenylenediamine and ammonium sulphide to detect Cu2+ ions in water samples [60]. To further explore the potential of the synthesized C-dots in real aqueous samples, measurements with the C-dots in pure water systems were taken, and a calibration curve illustrating the relationship between Cu2+ ion concentration and fluorescence intensity in water was established within the range of 0.0–42 μM (Figure 6). Two samples (Sample 1 and 2) corresponding to Cu2+ ions on their own and a metal ion mixture containing Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+, were prepared and tested. The results obtained for the known concentrations of Sample 1 and Sample 2 were consistent with their prepared concentrations (Table 1). The presence of interfering ions in Sample 2 did not affect the detection results, confirming the reliability of the detection method and its robustness against interference from the tested ions. To further evaluate the applicability of synthesized C-dots for Cu2+ ion detection in water samples, several real river samples were collected for testing. Water samples from rivers located in Hsinchu (G river), Taichung (T river), and Kaohsiung (H river) across Taiwan were analysed. The detection results in Table 1 indicate that the concentration in G river was 1.82 μM, in T river was 1.46 μM, and in H river was 20.4 μM. Notably, the copper concentration in H river was significantly higher than those in G and T rivers. These recovery values and their relative standard deviations met the standards, suggesting that the developed method is suitable for detecting Cu2+ ion in actual water samples.

Figure 6.

The copper ion calibration curve in pure double-distilled water.

Table 1.

Detection of Cu(II) in real water samples.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we successfully synthesized a novel class of luminescent carbon dots via a one-pot hydrothermal approach using a green precursor. The resulting nanomaterials exhibited excellent aqueous dispersibility, stable excitation-dependent photoluminescence, and strong tolerance to pH and ionic strength variations. Detailed spectroscopic and microscopic analyses confirmed their uniform morphology and favorable optical properties, with a quantum yield of 5.73%.

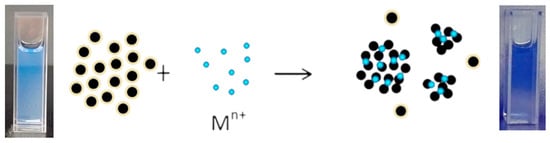

Importantly, the C-dots displayed selective and sensitive fluorescence quenching toward Cu2+, with a detection limit of 4.77 μM (~1.2 ppm), which is significantly below the USEPA guideline for copper in drinking water. As illustrated in Scheme 1, the sensing process follows a “turn-off” mechanism: under UV light (365 nm), the C-dot solution emits bright blue fluorescence, while the introduction of Cu2+ ions leads to coordination with surface –OH and –NH2 groups, forming non-radiative complexes that suppress photoluminescence. This concentration-dependent coordination reflects a predominantly static quenching pathway at lower Cu2+ levels, complemented by dynamic interactions at higher concentrations. Together, these findings highlight the potential of the synthesized C-dots as eco-friendly and biocompatible probes for environmental monitoring of Cu2+ ions.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the fluorescence “turn-off” mechanism between carbon dots (C-dots) and copper ions (Cu2+). Under UV illumination at 365 nm, the C-dot solution (left) emits bright blue fluorescence. Upon addition of Cu2+ ions, coordination occurs with surface –OH and –NH2 functional groups of the C-dots, forming non-radiative complexes that suppress photoluminescence. The quenched solution (right) appears visibly darker, demonstrating the Cu2+-induced fluorescence “turn-off” sensing mechanism.

These results are consistent with recent advances in carbon dot-based Cu2+ detection (Table 2), where ratiometric and dual-emission sensing platforms have been developed to improve robustness in complex matrices [61,62]. Heteroatom doping and surface functionalization have been widely employed to enhance Cu2+–C-dot interactions and quenching efficiency [63,64,65], while sustainable synthetic strategies, including green precursors and microreactor technologies, are increasingly emphasized for scalability and reproducibility [47,65,66]. In addition, red and near-red emissive C-dots have been introduced for biological applications [48], and portable platforms such as smartphone-assisted readouts have demonstrated the feasibility of on-site Cu2+ monitoring [62,67].

Table 2.

Comparison of representative carbon dot-based Cu2+ ion sensors with the present work.

Taken together, our study contributes to this growing body of research by offering a green, cost-effective synthesis route and demonstrating selective Cu2+ detection with practical sensitivity. Alongside ongoing developments in ratiometric sensing, surface engineering, and scalable production, these findings highlight the promise of carbon dots as versatile probes for real-world applications in environmental and biological Cu2+ monitoring.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors14010021/s1, Supplementary Figure S1: Calibration curve for the determination of fluorescence quantum yield of the C-dots. Supplementary Figure S2: Refractive index measurements of the C-dots at a wavelength of 589 nm. Supplementary Figure S3: Fluorescence decay curve (475 nm) before and after the addition of Cu(II) to C-dots. References [68,69] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-F.W.; methodology, C.-S.C., C.-F.W. and M.-W.L.; formal analysis, C.-S.C., C.-F.W. and M.-W.L.; investigation, C.-S.C., C.-F.W. and M.-W.L.; resources, C.-F.W.; data curation, C.-F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-S.C. and C.-F.W.; writing—review and editing, C.-S.C. and C.-F.W.; visualization, C.-S.C. and C.-F.W.; supervision, C.-F.W.; project administration, C.-F.W.; funding acquisition, C.-F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan for providing financial support and to Chung Shan Medical University for granting us access to essential instruments, significantly facilitating our research efforts. Our appreciation extends to the Instrumentation Center at National Tsing Hua University, with special thanks to Shang-Fang Chang, who offered valuable assistance with TEM techniques. Moreover, we are thankful to Ya-Hui Chen and the Precision Instrument Support Center at Feng Chia University for their expert support with XPS and XRD techniques. We also thank Chin-Hsuan Wan for helping with data analysis graphing and Liang Tsai of the Toson Technology Co. Ltd. (Hsinchu, Taiwan) for publication fee support. The collective contributions of these individuals and institutions have played a vital role in the successful completion of our research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| C-dots | carbon dots |

| PL | photoluminescence |

| QDs | quantum dots |

| QY | quantum yield |

| USEPA | the United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| MCLT | the metal-to-ligand electron transfer |

| UV–vis | ultraviolet–visible |

| FT-IR spectra | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| TCSPC | time-correlated single photon counting |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| Cu2+ | copper(II) |

| Fe3+ | iron(III) |

| Al3+ | aluminum(III) |

| Cr3+ | chromium(III) |

| Cr6+ | chromium(VI) |

| Pb2+ | lead(II) |

| As3+ | arsenic(III) |

| Cd2+ | cadmium(II) |

| Hg2+ | mercury(II) |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| QS | quinine sulfate |

| RI | refractive index |

| OD | optical density |

References

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Kc, S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebane, C.A. Bioavailability and Toxicity Models of Copper to Freshwater Life: The State of Regulatory Science. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 2529–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Saleem, M.H.; Bashir, S.; Ullah, S.; Peng, D. Copper environmental toxicology, recent advances, and future outlook: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 18003–18016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Machado, C.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J. Clinical and Forensic Signs Resulting from Exposure to Heavy Metals and Other Chemical Elements of the Periodic Table. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschke, R.; Eickhoff, A. Wilson Disease: Copper-Mediated Cuproptosis, Iron-Related Ferroptosis, and Clinical Highlights, with Comprehensive and Critical Analysis Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegambaram, M.; Manivannan, B.; Beach, T.G.; Halden, R.U. Role of Environmental Contaminants in the Etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matés, J.M.; Segura, J.A.; Alonso, F.J.; Márquez, J. Roles of dioxins and heavy metals in cancer and neurological diseases using ROS-mediated mechanisms. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1328–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency, U.E.P. Aquatic Life Ambient Fresh-Water Quality Criteria—Copper. 2007. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-02/documents/al-freshwater-copper-2007-revision.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Yuan, X.; Chapman, R.L.; Wu, Z. Analytical methods for heavy metals in herbal medicines. Phytochem. Anal. 2011, 22, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirichkov, M.V.; Polyakov, V.A.; Shende, S.S.; Minkina, T.M.; Nevidomskaya, D.G.; Wong, M.H.; Bauer, T.V.; Shuvaeva, V.A.; Mandzhieva, S.S.; Tsitsuashvili, V.S. Application of X-ray based modern instrumental techniques to determine the heavy metals in soils, minerals and organic media. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakayode, S.O.; Walgama, C.; Fernand Narcisse, V.E.; Grant, C. Electrochemical and Colorimetric Nanosensors for Detection of Heavy Metal Ions: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, J. Flourescence sensors for heavy metal detection: Major contaminants in soil and water bodies. Anal. Sci. 2023, 39, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.W.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, M.K.; Hussain, A.; Bui, X.T.; Ngo, H.H. A review of biosensor for environmental monitoring: Principle, application, and corresponding achievement of sustainable development goals. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.H.; Muthu, A.; Elsakhawy, T.; Sheta, M.H.; Abdalla, N.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Carbon Nanodots-Based Sensors: A Promising Tool for Detecting and Monitoring Toxic Compounds. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankoti, M.; Meena, S.S.; Mohanty, A. Exploring the potential of eco-friendly carbon dots in monitoring and remediation of environmental pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 43492–43523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Huang, B.B.; Lai, C.M.; Lu, Y.S.; Shao, J.W. Advancements in the synthesis of carbon dots and their application in biomedicine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2024, 255, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, D.K.; V, P.; Si, S.; Panigrahi, H.; Mishra, S. Carbon Dots and Their Polymeric Nanocomposites: Insight into Their Synthesis, Photoluminescence Mechanisms, and Recent Trends in Sensing Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11050–11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gong, J.; Zhou, H.; Yin, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, Q.; Lin, W.; Wang, H.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Z. Fluorescent carbon dots in PEC-GS/BG hybrids and their application for bioimaging. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1555995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, M.; Zhou, Y.; Nabil Amin Mustafa, M.; Eustace, A.J.; Giordani, S. CARBON DOTS: Bioimaging and Anticancer Drug Delivery. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202303982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sead, F.F.; Jadeja, Y.; Kumar, A.; M, R.M.; Kundlas, M.; Saini, S.; Joshi, K.K.; Noorizadeh, H. Carbon quantum dots for sustainable energy: Enhancing electrocatalytic reactions through structural innovation. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 3961–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, M.; Qiu, J.; Sun, Y.P. Design and fabrication of carbon dots for energy conversion and storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2315–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadamannil, N.N.; Shames, A.I.; Bisht, R.; Biswas, S.; Shauloff, N.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.M.; Jelinek, R. Light-Induced Self-Assembled Polydiacetylene/Carbon Dot Functional “Honeycomb”. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 22593–22603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, R.; Yukta, Y.; Mondal, J.; Kumar, R.; Pani, B.; Singh, B. Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Characterizations, and Recent Advancements in Biomedical, Optoelectronics, Sensing, and Catalysis Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 2086–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Razzaghi, M.; Ghorbanpoor, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Avci, H.; Akbari, M.; Hassan, S. Carbon dots in drug delivery and therapeutic applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 224, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, S.; Zapata, K.; Medina, O.E.; Rojano, B.A.; Taborda, E.A.; Cortés, F.B.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F.; Bailón-García, E.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Franco, C.A. Effect of the chemical nature of the nitrogen source on the physicochemical and optoelectronic properties of carbon quantum dots (CQDs). Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 5193–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, D.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Hocking, R.K.; Fox, B. Properties, synthesis, and applications of carbon dots: A review. Carbon Trends 2023, 12, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Junaid, H.M.; Tabassum, S.; Kanwal, F.; Abid, K.; Fatima, Z.; Shah, A.T. Metal Ion Detection by Carbon Dots-A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2022, 52, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.S.; Yokokawa, A.S.; Tseng, K.H.; Wang, M.H.; Ma, K.S.K.; Wan, C.F. A novel method for synthesis of carbon dots and their applications in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and glucose detections. Rsc Adv. 2023, 13, 28250–28261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, N.; Marinovic, A.; Yoshizawa, N.; Goode, A.E.; Fay, M.; Khlobystoyv, A.; Titirici, M.M.; Sapelkin, A. Structure and solvents effects on the optical properties of sugar-derived carbon nanodots. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigodanza, F.; Burian, M.; Arcudi, F.; Dordevic, L.; Amenitsch, H.; Prato, M. Snapshots into carbon dots formation through a combined spectroscopic approach. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurth, C.; Grabolle, M.; Pauli, J.; Spieles, M.; Resch-Genger, U. Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1535–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Han, Y.; Yuan, X.; Jing, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y. Efficient full-color emitting carbon-dot-based composite phosphors by chemical dispersion. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 15823–15831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, N.; O’Carroll, D.M. Long-term effects of impurities on the particle size and optical emission of carbon dots. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, H.M.; Duarte, A.J.; Esteves da Silva, J.C. Optical fiber sensor for Hg(II) based on carbon dots. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd ed.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Atchudan, R.; Edison, T.N.J.I.; Perumal, S.; Muthuchamy, N.; Lee, Y.R. Eco-friendly synthesis of tunable fluorescent carbon nanodots from for sensors and multicolor bioimaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 390, 112336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.F.; Wei, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.Q. Fluorescent Assay of FEN1 Activity with Nicking Enzyme-Assisted Signal Amplification Based on ZIF-8 for Imaging in Living Cells. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 4960–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Wu, R.S.; Wei, S.C.; Ross, G.M.; Chang, H.T. The analytical and biomedical applications of carbon dots and their future theranostic potential: A review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, F.; Hu, J.; Gao, W.H.; Zhang, M.Z. A Mini Review on pH-Sensitive Photoluminescence in Carbon Nanodots. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 605028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.; Klehs, K.; Rumble, C.; Vauthey, E.; Heilemann, M.; Fürstenberg, A. Universal quenching of common fluorescent probes by water and alcohols. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, M.H. The centenary of the Stern-Volmer equation of fluorescence quenching: From the single line plot to the SV quenching map. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2020, 42, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppal, V.V.; Melavanki, R.; Kusanur, R.; Bagewadi, Z.K.; Yaraguppi, D.A.; Deshpande, S.H.; Patil, N.R. Investigation of the Fluorescence Turn-off Mechanism, Genome, Molecular Docking In Silico and In Vitro Studies of 2-Acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23759–23770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapakshe, B.U.; Li, Y.H.; Corbin, B.; Wijesinghe, K.J.; Pang, Y.; Abeywickrama, C.S. Copper-Induced Fluorescence Quenching in a [2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole]pyridinium Derivative for Quantification of Cu in Solution. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandoss, S.; Palanisamy, S.; Priya, V.V.; Mohan, S.K.; Shim, J.J.; Yelithao, K.; You, S.; Lee, Y.R. Excitation-dependent multiple luminescence emission of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots for cysteine sensing, bioimaging, and photoluminescent ink applications. Microchem. J. 2021, 167, 106280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, M.J. Principles, mechanisms, and application of carbon quantum dots in sensors: A review. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 1266–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Zhou, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Q. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dots Prepared via Microchannel Method for Visual Detection of Copper Ions. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, M.N.; Alqarni, L.S.; Ibrahim, H.; El-Wekil, M.M.; Ali, A.B.H. First fluorometric sensor for dronedarone detection based on aggregation-induced quenching of red-emissive carbon dots: Application to pharmacokinetics. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2025, 468, 116535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C. Infrared Spectral Interpretation: A Systematic Approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, W.; Do, S.; Kim, J.H.; Seok Jeong, M.; Rhee, S.W. Control of Photoluminescence of Carbon Nanodots via Surface Functionalization using Para-substituted Anilines. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, R.; Alas, M.O.; Harputlu, E.; Repp, S.; Kremer, N.; Castellano, M.; Colak, S.G.; Ocakoglu, K.; Erdem, E. High-Capacitance Hybrid Supercapacitor Based on Multi-Colored Fluorescent Carbon-Dots. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ramon, J.A.; Bogireddy, N.K.R.; Giles Vieyra, J.A.; Karthik, T.V.K.; Agarwal, V. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dots Induced Enhancement in CO2 Sensing Response From ZnO-Porous Silicon Hybrid Structure. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Kang, L.; Gao, J.L.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.L. Preparation of Microcrystalline Cellulose-Derived Carbon Dots as a Sensor for Fe Detection. Coatings 2023, 13, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Das, P.; Bag, S.; Laha, D.; Pramanik, P. Synthesis, functionalization and bioimaging applications of highly fluorescent carbon nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, C.F.; Schaak, R.E. Tutorial on Powder X-ray Diffraction for Characterizing Nanoscale Materials. Acs Nano 2019, 13, 7359–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susi, T.; Pichler, T.; Ayala, P. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of graphitic carbon nanomaterials doped with heteroatoms. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayiania, M.; Smith, M.; Hensley, A.J.R.; Scudiero, L.; McEwen, J.S.; Garcia-Perez, M. Deconvoluting the XPS spectra for nitrogen-doped chars: An analysis from first principles. Carbon 2020, 162, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.Y. One-step green synthesized fluorescent carbon nanodots from bamboo leaves for copper(II) ion detection. Sens. Actuat B 2014, 196, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ganguly, S.; Bose, M.; Mondal, S.; Das, A.K.; Banerjee, S.; Das, N.C. A simplistic approach to green future with eco-friendly luminescent carbon dots and their application to fluorescent nano-sensor ‘turn-off’ probe for selective sensing of copper ions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato, R.; Bisauriya, R.; Antonaroli, S.; Cabibbo, M.; Moro, A.J. Colorimetric and Fluorescent Sensing of Copper Ions in Water through o-Phenylenediamine-Derived Carbon Dots. Sensors 2023, 23, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.J.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.Z.; Zhang, X.N.; Hu, Y.X.; Ouyang, S.G.; Li, N. Fluorescent and colorimetric dual-mode detection of Cu based on carbon dots. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.E.; Wu, T.T.; Lu, M.J.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Song, L.J.; Huang, X.Q.; Zhao, J.S.; Wang, T.L. An intelligent device with double fluorescent carbon dots based on smartphone for visual and point-of-care testing of Copper(II) in water and food samples. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Y.; Chen, M.X.; Mao, Z.; Deng, Y.Q.; He, J.; Mu, H.X.; Li, P.N.; Zou, W.C.; Zhao, Q. Synthesis of Up-Conversion Fluorescence N-Doped Carbon Dots with High Selectivity and Sensitivity for Detection of Cu Ions. Crystals 2023, 13, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Rezaei, A.; Shahlaei, M.; Asani, Z.; Ramazani, A.; Wang, C.Y. Selective and sensitive CQD-based sensing platform for Cu detection in Wilson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaye, R.C.; Gonzales KRG, A.D.; Plaza, K.M.T.; Silang, J.Y.D. Potentiality of nanosilica-doped carbon dots as fluorescence detector for copper (Cu2+) ions in simulated wastewater. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2023, 27, 777–789. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, B.I.; Hassan, A.I.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Ibrahim, A.E.; Saraya, R.E. Copper and nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots as green nano-probes for fluorimetric determination of delafloxacin; characterization and applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1327, 343175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Huang, X.; Kou, E.; Cai, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lei, B. Carbon dot based sensing platform for real-time imaging Cu2+ distribution in plants and environment. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 219, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahal, S.; Yousefi, N.; Tufenkji, N. Green Synthesis of High Quantum Yield Carbon Dots from Phenylalanine and Citric Acid: Role of Stoichiometry and Nitrogen Doping. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 5566–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.B.; Mirsky, S.K.; Shaked, N.T.; Gazit, E. High Quantum Yield Amino Acid Carbon Quantum Dots with Unparalleled Refractive Index. Acs Nano 2024, 18, 2421–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.