Abstract

This study explores the information misreporting behavior among channel members and the optimal pricing strategies in a dual-channel supply chain under information asymmetry, where the manufacturer operates an online channel, and the retailer operates an offline channel. More specifically, Stackelberg game models are developed for both manufacturer-led and retailer-led scenarios to analyze the impact of different power structures on the pricing decisions, information misreporting behavior, and the profits of both individual members and the overall supply chain. The main findings are as follows: (1) The power structure exerts a pivotal influence on the misinformation strategies adopted by supply chain members. (2) As the retailer’s misinformation factor increases, the wholesale price decreases, whereas the traditional retail price rises. (3) The profit advantage from dominance is counteracted by misreporting, and the extent of this effect depends on cross-price sensitivity. (4) Followers often resort to information misreporting to maximize their own profits, a strategy that benefits the misreporting party individually yet undermines the total supply chain profit.

MSC:

91A80

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of e-commerce, the dual-channel supply chain structure —integrating offline retail with online direct sales—has progressively become the dominant model in modern supply chain operations [1]. Companies across various industries, such as ZARA, Lenovo, and IBM, routinely collect diverse information from multiple channels. In such dual-channel systems, participants often operate with asymmetric information and varying degrees of channel power, with each member possessing private information not shared with others [2]. For instance, manufacturers typically hold private knowledge regarding raw material costs, product development, and production expenses, whereas retailers possess confidential information related to sales costs and market demand forecasts. To safeguard their own interests, supply chain members often resort to withholding critical information [3]. This combination of privately held information and profit-maximizing motives frequently leads to widespread information misreporting within dual-channel supply chains. Examples include manufacturers overstating production costs or retailers distorting sales cost data in response to market fluctuations [4].

Information misreporting behavior refers to a strategic action where the information-advantaged party, driven by profit-maximization motives, deliberately distorts private information under asymmetric information conditions. Based on the acting entities, such behavior can be categorized into two main types: unilateral and bilateral information misreporting. (1) Unilateral information misreporting occurs when only one party—either the manufacturer or the retailer—engages in misreporting. It can be further classified as manufacturer misreporting or retailer misreporting. (2) Bilateral information misreporting arises when both upstream and downstream members, i.e., the manufacturer and the retailer, misreport their information simultaneously. This directly disrupts market mechanisms, distorts market signals, and may consequently lead to market failure.

This naturally leads to several key questions: Is misreporting a strategically beneficial maneuver? What impact does it have on the revenues of individual members and the supply chain as a whole? Furthermore, how do varying power structures shape the subsequent behaviors in information sharing and pricing? Our study delves into these pivotal issues.

In terms of channel members’ dominance, existing studies on dual-channel supply chains have largely concentrated on how power structures influence pricing strategies, coordination mechanisms, and overall supply chain performance. For instance, Qiu and Xu [5] investigated the effect of manufacturers’ network efficiency on enterprise pricing and performance under three distinct power configurations, considering the fairness concerns of e-commerce platforms. Pu et al. [6] analyzed how channel power structures shape operational decisions in manufacturer-led dual-channel models and proposed two-stage pricing contracts to coordinate supply chains across different governance modes. Under both cooperative and non-cooperative game settings, Saha et al. [7] studied the optimal pricing in a multi-channel supply chain with demand sensitivity to both price and delivery lead time. Xu et al. [8] analyzed the impact of retail costs, including fixed, linear, and quadratic costs, on the optimal channel structures in a dual-channel supply chain with a monopoly manufacturer, an independent retailer, and diverse consumer segments. Additionally, Zheng et al. [9] further analyzed pricing, coordination, and power structure effects within the context of dual-channel closed-loop supply chains. Xiao et al. [10] investigated how store brand introduction affects pricing and profit dynamics in dual-channel supply chains. The advantages of supply chain members acting as leaders in electronic retail channels were highlighted [11], and revenue dynamics were analyzed when manufacturers, retailers, or platforms take on leadership roles [12]. Wang et al. [13] introduced the risk aversion behavior of channel members, revealing that manufacturers may profit by concealing production costs. The effects of misreporting strategies by competing manufacturers on supply chain performance were explored by Yan et al. [14], emphasizing the need to account for consumers’ cross-price elasticity. Furthermore, the role of manufacturer effort cost coefficients and consumer heterogeneity preferences was examined under four power structures [15].

With respect to information misreporting by channel members, there are mainly two research streams: manufacturers’ private information misreporting and retailers’ private information misreporting. On the one hand, many scholars explored issues such as the optimal pricing strategies, the revenues of supply chain members, and the coordination mechanisms in supply chains under manufacturer information asymmetry. Gao et al. [16] revealed the reasons why manufacturers and retailers can benefit from information asymmetry in the sales process in retailer dual-channel supply chains. Zhou et al. [17] found that when manufacturers possess exclusive information, they should determine the prices for both online and offline channels based on various factors, such as demand uncertainty and the sensitivity of demand to prices. A comparative analysis of expected profits and utilities under asymmetric and symmetric information frameworks was conducted by Li et al. [18], revealing distinct outcomes for supply chain members. Yang [19] designed a revenue-sharing contract model under complete information and asymmetric information in a dual-channel supply chain. Jiang and Zhao [20] examined the dual effects of information sharing on retailers—generating both competitive advantages and strategic vulnerabilities. Notably, manufacturers’ private sales costs have been identified as a key determinant of profit-booking decisions [21]. Jiang et al. [22] investigated the government’s penalty provisions and contracting mechanisms in a bioenergy supply chain, focusing on how asymmetric quality information between power plants and farmers affects decision-making and contract design. In dual-channel contexts, Wu et al. [23] examined cooperative advertising and retailers’ demand–information sharing in a dual-channel supply chain consisting of a manufacturer and a retailer, where the manufacturer dominates the decision-making process. In reference [24], manufacturer CSR and recycling difficulty misreporting across three power structures was examined, and revenue-sharing/two-part pricing contracts were proposed for Pareto improvements in closed-loop supply chains. The blockchain technology was used by Yang et al. [25] to address farmers’ misrepresentation of product freshness information, and the cost thresholds for its effective implementation were identified. On the other hand, retailers also hold some private information, such as sales costs and market demand, leading to information asymmetry in the dual-channel supply chain. Tian et al. [26] analyzed the strategic interactions between supply chain members under conditions where retailers hold proprietary information and exhibit risk aversion. A signaling game was developed based on inequity aversion theory to analyze supplier pricing strategies under asymmetric cost information and retailer fairness concerns [27]. Xiao et al. [28] discussed the adverse situation where retailers lose their information advantage during the acquisition process and proposed a corresponding adjustment contract. Furthermore, Lin et al. [29] noted that when retailers do not share information, manufacturers can only set direct selling prices based on expectations. Zong et al. [30] investigated manufacturers’ misreporting of product greenness and its effects on supply chain decisions and profitability, finding that such behavior increases manufacturer profits while harming retailer and overall supply chain performance.

In summary, existing studies on power structures have primarily examined their effects on the optimal pricing, member profits, and contract coordination mechanisms. However, these studies fail to consider the information misreporting behavior among channel members. Meanwhile, studies on information misreporting mainly focus on pricing decisions in cases of manufacturer or retailer misreporting, cost information misreporting, and demand information misreporting. Nevertheless, they ignore the impact of different power structures on the information misreporting behavior of channel members, market demand, pricing decisions, and supply chain performance. To address these gaps, this paper investigates the information misreporting behaviors and pricing decisions of manufacturers with private production cost information and traditional retailers with private sales cost information across different power structures. It also offers a comparative analysis of how these structures influence the pricing strategies of channel members and the performance of the supply chain as a whole. Table 1 compares our research with existing studies on power structure and information misreporting in a dual-channel supply chain. As shown in Table 1, the main contribution of our research is to simultaneously consider power asymmetry and cost information misreporting behavior among members in a dual-channel supply chain, and to analyze the misreporting behavior and optimal pricing strategies of the manufacturers and retailer under different power structures.

Table 1.

A comparative analysis: existing studies versus our research work.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the main research problem and the assumptions of the proposed model. In Section 3, the pricing game models under manufacturer-led and retailer-led scenarios are developed considering information misreporting among supply chain members. Section 4 presents the sensitivity analysis of these pricing models. Finally, Section 5 offers a comprehensive conclusion.

2. Problem Description and Model Assumptions

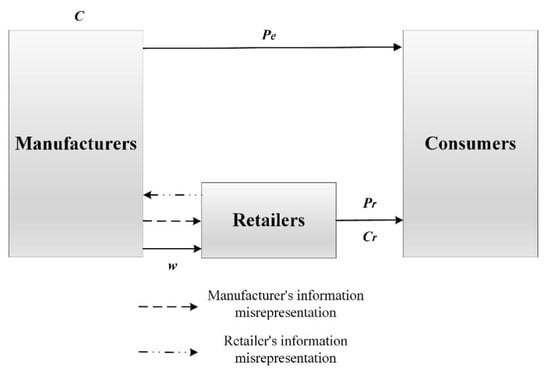

This study examines a dual-channel supply chain comprising a manufacturer and a retailer, in which the manufacturer sells directly online, and the two members engage in information misreporting. The model framework is illustrated in Figure 1, where solid and dashed lines represent material and information flows, respectively.

Figure 1.

Dual-channel supply chain model with information misreporting behavior.

As shown in Figure 1, the manufacturer distributes products through two primary channels: (1) a traditional retail channel, where the retailer buys products at wholesale price w and then sells them to consumers at price ; (2) a direct online channel, where the manufacturer sells to consumers at price . All relevant notations and their definitions are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notations and their descriptions.

The assumptions are as follows:

- (1)

- The products produced and sold in the supply chain are homogeneous;

- (2)

- The manufacturer and retailer are both risk-neutral and fully rational;

- (3)

- Production and sales are balanced, with no shortages or inventory;

- (4)

- The wholesale price is greater than the unit manufacturing cost, i.e.,

- (5)

- The unit retail cost is less than the unit manufacturing cost, i.e.,

- (6)

- The traditional retail price is greater than the wholesale price, i.e.,

- (7)

- The unit production cost and the unit retail cost are private information of the manufacturer and the retailer, respectively.

The per-unit retail cost refers to the cost incurred by the retailer in providing services. Traditional retailers strive to capture a larger consumer market by offering high-quality pre-sales services to attract buyers. Examples include complimentary tasting for food products, trial fittings for apparel, and well-decorated physical stores.

Based on literature [1,6], the market demand functions for the traditional retail channel and the manufacturer’s online direct sales channel can be denoted as follows.

Note that is the foundational market demand. The market share for the traditional retail channel is expressed as , while the online direct sales channel is captured by . According to reference [6], the coefficient b represents the sensitivity to price changes across channels, and it is bound within .

Let () represent the cost information misrepresentation factor for each supply chain member. Specifically, denotes the misrepresentation factor related to the retailer’s unit retail cost information, while indicates the misrepresentation factor of the manufacturer’s unit production cost information. Regarding the interpretation of these factors: indicates under-reporting; signifies truthful reporting, and denotes an over-reporting [13]. In terms of profit notation, ““ denotes the manufacturer’s disclosed profit under production cost misrepresentation, whereas “” reflects its true profit under accurate cost reporting. Similarly, ““ represents the retailer’s stated profit under potential sales cost misrepresentation, whereas “” indicates its actual profit under truthful reporting. Based on the given demand function, the profit functions for both the manufacturer and the retailer can be derived.

Using Equations (1) and (2), we formulate the manufacturer’s disclosed and actual profit functions.

Similarly, the retailer’s disclosed and actual profit functions are expressed as follows.

Since the total supply chain profit equals the sum of the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits, the actual profit function of the supply chain can be further derived.

3. Pricing Modeling of Dual-Channel Supply Chains Under Different Leadership Structures

This section investigates how different power structures influence optimal pricing and information misreporting behaviors in a manufacturer-led dual-channel supply chain. Through a comparative analysis of member profits under information misreporting, we assess the strategic value and managerial implications of such practices.

3.1. Information Misrepresentation and Manufacturer-Led Pricing Model

In the manufacturer-dominant model, we find that the retailer’s misreporting factor depends on cross-price elasticity. The retailer often engages in strategic overstatement of sales costs to achieve short-term profit gains. Consequently, such strategic manipulation proves detrimental to the long-term health of the overall supply chain.

3.1.1. Information Misrepresentation and Optimal Pricing in Dual-Channel Supply Chain

When both the manufacturer and the retailer engage in information misreporting (i.e., , their strategic interaction can be modeled as a Stackelberg leader-follower game. Applying backward induction under the manufacturer’s leadership, the retailer’s second-stage optimization problem is formulated as follows:

The retailer’s optimal response function can be derived as:

Substituting Equation (9) into Equations (1)–(3), and after rearranging, we obtain the manufacturer’s optimization problem in the first stage, denoted as:

Given , and , the determinant of the Hessian matrix corresponding to is 2 It is evident that the Hessian matrix is negative definite, making a concave function in terms of and . Let , the manufacturer’s optimal direct sale price and optimal wholesale price can be derived as:

By substituting Equations (11) and (12) into Equation (9), we can derive the retailer’s optimal retail price as follows:

By substituting the optimal solution obtained above, Equations (11)–(13), into Equations (4) and (6), and then computing the first-order partial derivatives, we obtain . Let , then the optimal misrepresentation factors can be determined as shown below, where superscript “MN” denotes the manufacturer-led dual-channel supply chain model with information misrepresentation.

Proposition 1.

Under the manufacturer-dominant model, the manufacturer does not misrepresent its production cost information, while the retailer chooses to overstate its sales cost information if and only if . Moreover, the retailer’s misrepresentation factor increases as the cross-price sensitivity coefficient rises.

Proof of Proposition 1.

Based on the derived optimal misrepresentation factors, we have , and . As previously discussed, means that there is no misrepresentation of cost information, while suggests an overstatement of cost information. Therefore, the manufacturer accurately discloses its production cost information. The positive derivative further indicates that the retailer’s misrepresentation factor rises in tandem with the increase in the cross-price sensitivity coefficient. Next, we will continue to prove that “the retailer chooses to overstate its sales cost information if and only if .

Assume we have > 3 > > (since > 0). Thus, holds. This means that holds if and only if . □

Proposition 1 demonstrates that in a manufacturer-dominant dual-channel sales model, the manufacturer elects not to misrepresent production cost information, whereas the retailer opts to overstate sales cost information under specific conditions. In other words, when the manufacturer holds a dominant position in the supply chain, the retailer’s bargaining power is diminished. As a result, the manufacturer can capitalize on its advantageous status to increase wholesale prices, thereby eliminating the need to inflate cost data. In contrast, when the base market demand substantially exceeds the sum of the retailer’s cost and the adjusted channel competition cost , the marginal benefit gained from over-reporting outweighs the potential risks, thus creating incentives for misreporting. This condition reflects how high-margin environments in real markets can induce fraudulent behavior. This strategy is employed to enhance bargaining leverage in wholesale price negotiations, thus encouraging the manufacturer to lower the product’s wholesale price.

Based on the established assumptions, implies that the manufacturer does not misrepresent its private production cost information, while the retailer opts to inflate its reported private sales cost information. Therefore, under the manufacturer-dominant model, the manufacturer’s optimal direct sales channel price, wholesale price, and the retailer’s optimal traditional retail price are, respectively:

To ensure the establishment of the wholesale mechanism, it is necessary for , meaning that must hold true. From this, we derive that .

Proposition 2.

Under the manufacturer-dominant mode, the direct sales channel price is not influenced by the retailer’s misinformation factor. As the retailer’s misinformation factor increases, the wholesale price decreases, whereas the traditional retail price rises.

Proof of Proposition 2.

and , Proposition 2 is thereby proven. □

Based on Proposition 2, it is clear that the retailer’s misinformation factor is directly proportional to the cross-price sensitivity coefficient. A higher coefficient leads the retailer to consistently overstate its sales cost information. In response, the retailer is compelled to further raise the traditional retail price in order to convince the manufacturer of the credibility of its reported cost information, thereby inducing the manufacturer to lower the product’s wholesale price. In this case, both the retailer’s markup on the traditional retail price and the manufacturer’s wholesale price reduction become more pronounced. Even as the retailer inflates the traditional retail price, the manufacturer maintains the direct sales price unchanged, aiming to achieve higher sales volume through thinner margins.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Value of Retailer’s Misreporting on Sales Cost Information

Under truthful reporting by both channel members , we refer to the model as the manufacturer-dominant, no-misreporting case, denoted by “MY”. Applying the same solution approach as before, the corresponding optimal equilibrium solutions are obtained as follows.

By comparing the optimal profits of channel members under both the conditions of no-misinformation and retailer misinformation, we can derive the value created by misreporting sales cost information for the manufacturer, the retailer, and the supply chain. This value is manifested as the changes in channel member profits, leading to Proposition 3.

Proposition 3.

In the manufacturer-dominant model, when and , the retailer’s profit will increase as the degree of misrepresentation of sales cost information rises. However, this will correspondingly lead to a decrease in the profit of both the manufacturer and the overall supply chain.

Proof of Proposition 3.

The change in the manufacturer’s profit before and after the misrepresentation of sales cost information can be denoted as:

Let . Then its derivative When , we have , which implies that is a monotonically decreasing function of . Given that and it follows that . Similarly, we can prove and . □

Proposition 3 suggests that the dominant manufacturer can take advantage of its superior position to raise the wholesale price to maximize its profits. Meanwhile, the disadvantaged retailer chooses to exaggerate its sales cost information to induce the manufacturer to lower the wholesale price. Comparing the optimal equilibrium solutions in these two situations, it is evident that the retailer’s exaggeration of sales cost information can reduce both the manufacturer’s profits and the overall profit of the supply chain.

3.2. Information Misreporting and Pricing Model Under Retailer Dominance

In the retailer-dominant model, the manufacturer’s misrepresentation factor is influenced by cross-price elasticity. To enhance profitability, manufacturers tend to misreport production cost information. This behavior leads to an increase in the direct sales price. However, such misreporting also results in reduced market demand, which ultimately undermines the overall profit of the supply chain. It should be noted that under the retailer-dominant scenario, the profit functions of the manufacturer and the retailer are given by Equation (3) and Equation (5) in Section 2, respectively.

3.2.1. Information Misreporting and Optimal Pricing Strategy in Dual Channel Supply Chain

Under the retailer-dominant model, when both the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s misrepresentation factors are nonzero (i.e., , the two parties engage in a Stackelberg game. In this setting, the retailer, as the leader, first sets a retail markup that maximizes its benefits, i.e., . The manufacturer, acting as the follower, then determines the optimal wholesale price and direct sales price after observing the retailer’s decision. By applying backward induction, the optimal pricing decisions of the channel members under retailer dominance are derived as follows.

The superscript ‘RN’ represents the dual-channel supply chain model under retailer dominance with the presence of information misreporting. With each channel member maximizing their profits, the equilibrium solutions are substituted into their respective true profit functions, namely Equations (4) and (6). The solution for the optimal information misreporting factor for the channel members can be obtained as follows:

Proposition 4.

Under the retailer -dominant model, the retailer does not misrepresent its sales cost information, while the manufacturer chooses to overstate its production cost information if and only if . Moreover, the manufacturer’s misrepresentation factor increases as the cross-price sensitivity coefficient rises.

Proof of Proposition 4.

Based on the derived optimal misrepresentation factors, we have , and then if and only if . □

Proposition 4 reveals that in a retailer-led dual-channel supply chain, retailers do not engage in misreporting sales cost information. By contrast, manufacturers in a subordinate position may overstate their production costs under certain conditions to strengthen their negotiating leverage over wholesale prices—a behavior consistent with observed practice. When the retailer holds a dominant position, it can leverage its channel power to secure lower wholesale prices from manufacturers, thereby eliminating the need for cost misrepresentation. In response, manufacturers facing such power asymmetry may resort to inflating production cost information as a strategic measure to improve their bargaining position with the retailer.

According to the assumptions made earlier, indicates that the retailer does not choose to misreport its private sales cost information, while the manufacturer opts to overstate its private production cost information. Consequently, under the retailer’s dominance, the optimal direct sales channel price, wholesale price, and traditional retail price for the retailer are as follows:

To ensure the validity of the wholesale mechanism, condition needs to be fulfilled, which requires . Through calculations, we can derive .

Proposition 5.

Under the retailer-dominant model, the direct sales channel price, wholesale price, and traditional retail price all increase with the rise of the manufacturer’s misreporting factor. When the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is relatively high, a decrease in the manufacturer’s misreporting factor negatively impacts the equilibrium solution of the supply chain.

Proof of Proposition 5.

Given that , , and it follows that Proposition 5 holds true holds. □

Combining Proposition 4, and Proposition 5 indicates that when manufacturers face large retail enterprises, they lack pricing dominance. However, manufacturers opt to overstate their private production cost information to increase the wholesale price.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Value of Misreporting Manufacturer’s Production Cost Information

Using “RY” to represent the dual-channel supply chain model under retailer dominance without information misreporting, we can calculate the optimal pricing scheme for the supply chain channel members under this situation:

By comparing and analyzing the optimal profits of supply chain members under two scenarios—without information misreporting and with manufacturer information misreporting, we can derive the value generated by the misreporting of production cost information for manufacturers, retailers, and the supply chain. That is, it manifests as changes in the profits of the channel members. From this, we can establish Proposition 6.

Proposition 6.

In the retailer-dominant model, when and , the manufacturer’s profit will increase as the degree of misrepresentation of production cost information rises. However, this will correspondingly lead to a decrease in the profit of both the retailer and the overall supply chain.

Proof of Proposition 6.

The change in the manufacturer’s profit before and after the misrepresentation of production cost information can be denoted as:

Let . Then its derivative . When , we have , which implies that is a monotonically increasing function of . Given that and , it follows that . Similarly, we can prove and . □

Proposition 6 indicates that in a retailer-dominated supply chain, the retailer leverages its advantageous position to compel the manufacturer to reduce the wholesale price. In response, the disadvantaged manufacturer may overstate its private production cost information to raise the wholesale price and mitigate its losses. A comparison of the optimal equilibrium solutions under the two scenarios reveals that as the manufacturer continues to overstate its costs, it simultaneously increases the direct sales channel price in an attempt to justify its position. This undermines the competitive advantage afforded by the retailer’s dominance. Furthermore, the rise in the wholesale price forces the retailer to increase the traditional retail price, which reduces demand in the traditional channel and erodes the retailer’s profits. At the same time, inter-channel information misreporting prevents members from accurately discerning each other’s true decisions, ultimately impairing the overall profit of the supply chain.

4. Sensitivity Analysis

Given that , it suffices to ensure in order to guarantee that the equilibrium solutions under both power structures satisfy . All subsequent analyses are conducted under this condition.

We examine how information misreporting by retailers and manufacturers under different power structures affects the optimal equilibrium solutions and overall supply chain profit. Given the involvement of misreporting factors from both parties and the resulting computational complexity, the comparison is performed via numerical example analysis. Note that the sensitivity analysis is carried out under the ceteris paribus assumption—that is, we focus on how variation in a specific parameter influences optimal pricing or member profits, independent of simulation run counts.

Following references [5,14], we set the parameters as follows: a = 200, θ = 0.5,, c = 8, with . Since the misreporting factors of manufacturers and retailers are influenced by the cross-price sensitivity coefficient, this section investigates how the optimal pricing decisions vary with misreporting factors ( and ) under two cases: a lower cross-price sensitivity (b = 0.4) and a higher one (b = 0.8). We also conducted simulation analyses for b = 0.3 and b = 0.7, which yielded results consistent with those for b = 0.4 and b = 0.8. To avoid redundancy, only the simulation results for b = 0.4 and b = 0.8 are presented below. The cross-price elasticity coefficient b can be estimated based on the demand and price information of the two channels. In practice, managers can empirically estimate the value of parameter b by analyzing historical sales data of the dual channels.

4.1. Variations in Profit with Misreporting Degree Under Different Dominance Structures

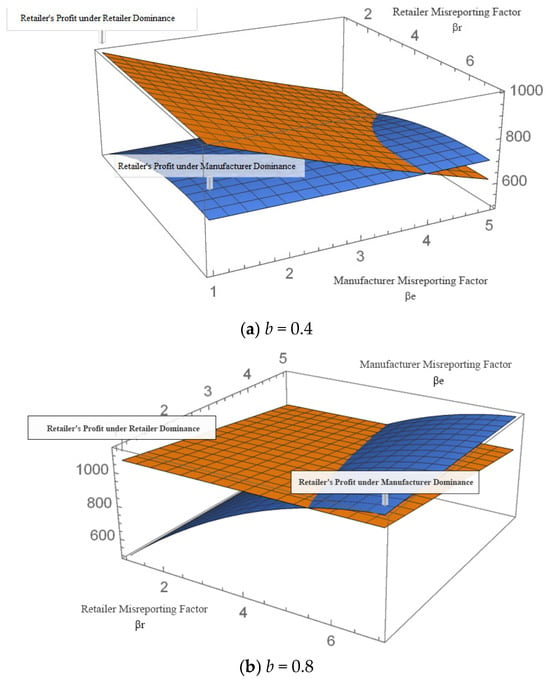

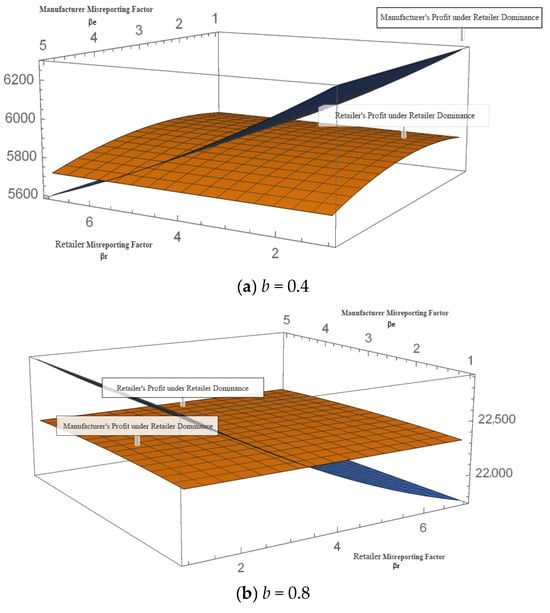

The above parameters are substituted into the actual profits of manufacturers and retailers. In the manufacturer-dominant mode, only retailers misreport cost information, while in the retailer-dominant mode, only manufacturers’ misreport cost information. Therefore, in analyzing the impact of information misreporting on the number’s respective profits, we only consider misreporting behavior from the counterpart. The solution of the proposed supply chain pricing models requires symbolic computation. The Mathematica software has unique advantages in handling symbolic computation and numerical simulation. Using the Mathematica 12.3.1.0, we can plot the changes in the profits of retailers and manufacturers with the information-misreporting factor under the two dominance structures, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, where (a) and (b) represent the simulation results for b = 0.4 and b = 0.8, respectively.

Figure 2.

Retailer’s Profit Variation with Misreporting Factor under Different Dominance Structures.

Figure 3.

Changes in manufacturer’s profits with misinformation factor under different dominance structures.

Figure 2 shows that under the manufacturer-dominant model, the retailer’s profit increases as the retailer’s misreporting factor increases, and the rate of increase is positively correlated with the size of the cross-price sensitivity coefficient, because the retailer’s misreporting factor and the cross-price sensitivity coefficient are positively correlated. This shows that when the manufacturer is the dominant decision-maker, the retailer maximizes profits by over-reporting its private sales cost information.

Under the retailer-dominant model, the retailer’s profit decreases as the manufacturer’s misreporting factor increases, and the rate of decrease is negatively correlated with the cross-price sensitivity coefficient, because the manufacturer’s misreporting factor and the cross-price sensitivity coefficient are negatively correlated. When facing a large retailer, the manufacturer loses its dominant pricing power. In this scenario, the manufacturer maximizes its own benefits by over-reporting private production cost information.

It is also found that when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is relatively large, there is a threshold for the misreporting factors of both parties so that the impact of the channel member’s information misreporting behavior on retailer profits is significantly stronger than the impact of dominance on retailer profits.

In Figure 3, we observe that under a manufacturer-dominant structure, the manufacturer’s profit decreases as the retailer’s misinformation factor increases. Notably, when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is relatively high, the manufacturer’s profits in a manufacturer-dominant structure far exceed their profits when the coefficient is low. This is attributed to the fact that with a higher cross-price sensitivity coefficient, the retailer’s misinformation factor also rises. Consequently, the retailer marks up prices more aggressively. Meanwhile, the manufacturer maintains steady direct channel prices, adopting a low-margin, high-volume strategy, which garners increased revenue.

Under a retailer-dominant structure, the manufacturer’s profit gradually decreases as the misinformation factor grows. A striking observation is that when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is relatively low, there exists a threshold for both parties’ misinformation factors. Beyond this threshold, the impact of misinformation on the manufacturer’s profit is significantly more pronounced than the influence of the dominant structure itself.

4.2. Changes in Optimal Price with the Degree of Information Misreporting Under Different Dominance Structures

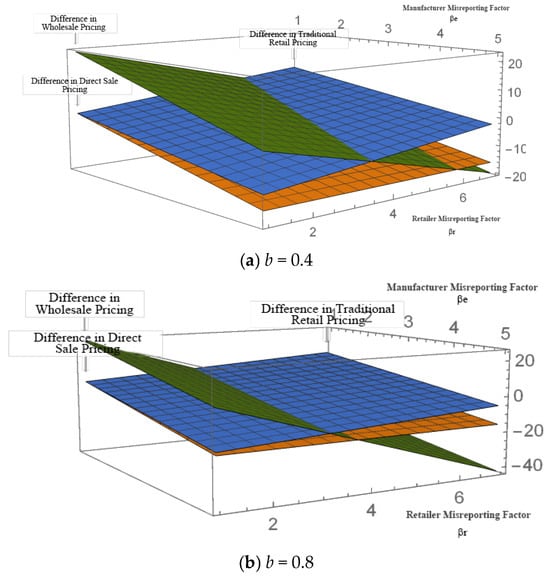

Under the two different dominance structures, manufacturer-dominant and retailer-dominant, the variation in the optimal pricing difference of the channel members concerning the misinformation factors of both parties is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Variation in optimal pricing difference with misreporting factor under different dominance structures.

Based on Figure 4, it is evident that information misreporting by channel members directly influences selling prices. Specifically, in the manufacturer-dominant model, the traditional retail price under retailer misreporting is higher than that in the retailer-dominant model under no misreporting. Similarly, in the retailer-dominant model, the direct sales price under manufacturer misreporting exceeds the corresponding price in the manufacturer-dominant model without misreporting.

Previous research indicates that in the absence of misinformation, both direct sales and traditional retail prices are equivalent regardless of the leadership structure. However, when misinformation behavior is present, sales prices are influenced by this behavior. This is because, under a retailer-dominant scenario, manufacturers might exaggerate their production costs. To make retailers believe this, manufacturers raise the direct sales channel price, resulting in a higher price than when there is no misinformation under the manufacturer-dominant model. As mentioned earlier, the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is inversely proportional to the manufacturer’s misinformation factor. Comparing the two scenarios in Figure 4, when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is small, the price difference between the two leadership structures becomes more pronounced with variations in the manufacturer’s misinformation factor. Similarly, under the manufacturer-dominant model, when retailers exaggerate their sales costs to convince manufacturers, the retail channel price is higher than the traditional channel retail price during retailer leadership.

Regarding the wholesale price, past research suggests that the wholesale price under the manufacturer-dominant model is higher than under the retailer-dominant model. The wholesale price is sensitive to the dominant structure. However, when misinformation behavior exists, the magnitude of the wholesale price is constrained by misinformation factors from both parties. As the manufacturer’s misinformation factor increases, its dominance over the wholesale price gradually diminishes. This reduction is more pronounced when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is smaller. As the retailer’s misinformation factor increases, the manufacturer’s dominance over the wholesale price also diminishes. Yet, when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is larger, the constraining effect of the retailer’s misinformation behavior becomes more pronounced.

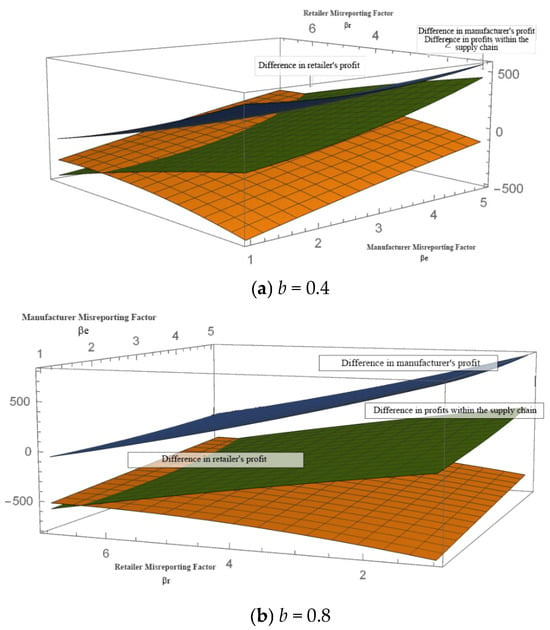

4.3. Variations in Profit with the Degree of Misinformation Under Different Leadership Structures

The difference in profits for channel members and the supply chain under both manufacturer and retailer leadership structures varies with changes in the misinformation factor, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Changes in the D-value of channel members’ profits under different dominance structures with the information misrepresentation factor.

As observed from Figure 5, the difference in manufacturer profits under both leadership models is directly influenced by the magnitude of the channel member’s misinformation factor. Specifically, as the retailer’s misinformation factor increases, the difference in manufacturer profits decreases. When the retailer’s misinformation factor reaches its maximum value, the manufacturer’s dominant role no longer offers a competitive advantage. As previously discussed, the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is positively correlated with the retailer’s misinformation factor. Comparing the two scenarios in Figure 5 reveals that when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is high, the retailer’s misinformation factor imposes a more pronounced constraint on the manufacturer’s dominant role. The magnitude of the manufacturer’s misinformation factor does not significantly influence the profit difference between the two.

The difference in retailer profits under both manufacturer and retailer leadership models increases as both parties’ misinformation factors grow. When the cross-sensitivity coefficient is relatively low, as the misinformation factors from both sides continue to rise, the retailer no longer holds a dominant advantage. However, when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is higher, the retailer’s dominant role gradually weakens with the increase in misinformation factors from both parties but still retains its dominant position.

Regarding the entire supply chain’s profits, as the manufacturer’s misinformation factor increases, the profits under manufacturer dominance progressively exceed those under retailer dominance. This difference is more pronounced when the cross-price sensitivity coefficient is relatively low. Conversely, as the retailer’s misinformation factor increases, the profits under manufacturer dominance gradually become less than those under retailer dominance.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzes the impact of power structures on misinformation behaviors and optimal pricing strategies, as well as members’ profits, in a dual-channel supply chain. The key findings are summarized as follows:

Power structure dictates misinformation strategies. In a manufacturer-led chain, the retailer over-reports its sales costs if, and only if,

- (1)

- , with the degree of misreporting increasing the cross-price sensitivity. Conversely, under retailer leadership, the manufacturer may over-report production costs, but its misreporting decreases as b increases.

- (2)

- Sales prices are directly influenced by misinformation behaviors. The manufacturer-led model results in a lower direct channel price but a higher traditional retail price compared to the retailer-led model. Furthermore, a manufacturer’s wholesale price power diminishes as the mutual misreporting intensifies.

- (3)

- The profit advantage of dominance is eroded by misreporting, and the cross-price sensitivity modulates this effect. Specifically, when b is low, misreporting’s impact on the retailer’s profit is weaker than the power structure’s effect, while its impact on the manufacturer is stronger. This dynamic reverses when b is high.

In summary, misinformation behavior, intrinsically linked to the power structure and cross-price sensitivity, critically impacts the pricing and profitability of members in supply chain. To mitigate these disruptive effects, the dominant firm should implement incentive-aligned mechanisms (e.g., cost-sharing or penalty contracts) to discourage deception and approach Pareto improvement.

However, there are some limitations to this study. First, it relies on a linear demand assumption, whereas real-world demand is often nonlinear. Second, the analysis focuses only on cost misreporting. In future studies, misinformation regarding demand or service levels can be taken into account. Finally, the simulation parameters, although adapted from the literature, remain somewhat subjective. Empirical data would strengthen the validity of future findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and S.Z.; methodology, Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y., S.Z. and G.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. and C.L.; supervision, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China, Grant Nos. 25YJAZH232, 24YJCZH445; the National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China, Grant Nos. 72471105, 72001096, 72374088, 72071107; and the Qing Lan Project for Higher Education Institutions in Jiangsu Province.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Zang, H.; Ruan, J. Game analysis in a manufacturer dual-channel supply chain with different power structures. China J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 28, 154–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Shu, L.; Yao, J. Optimal pricing and service level in supply chain considering misreport behavior and fairness concern. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 174, 108759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Wang, C.; Xu, J. The impact of trade credit on information sharing in a supply chain. J. Omega 2022, 110, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Guo, H. Telling truth or lying: Bilateral information incentive and supply chain efficiency. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 35, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Xu, B. Analysis of the influence of online sales efficiency on dual channel game of fairness concern under different power modes. Stat. Decis. 2019, 35, 56–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Lin, X.; Li, D. Operation efficiency and coordination mechanism of dual-channel supply chains under different channel power structures. Logist. Sci-Tech 2017, 40, 117–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Modak, N.M.; Panda, S.; Sana, S.S. Managing a retailer’s dual-channel supply chain under price- and delivery time-sensitive demand. J. Model. Manag. 2018, 13, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Long, D. The optimal channel structure with retail costs in a dual-channel supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Dual-channel closed loop supply chains: Forward channel competition, power structures and coordination. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3510–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Niu, W.; Zhang, L.; Xue, W. Store brand introduction in a dual-channel supply chain: The roles of quality differentiation and power structure. Omega 2023, 116, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; He, X. Strategic dual-channel pricing games with e-retailer finance. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, Y. A competitive dual recycling channel in a three-level closed loop supply chain under different power structures: Pricing and collecting decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gu, C.; Zhang, B. Pricing decision in dual-channel supply chain under risk-aversion and asymmetric information. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 21, 20–25+34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Decision analysis of retailer-dominated hybrid channel supply chain under the asymmetric cost information. China J. Manag. Sci. 2015, 23, 124–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Wu, S. Decision making of two-echelon supply chain with dual channel under different power structures. Syst. Eng. 2021, 39, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Guo, L.; Orsdemir, A. Dual channel distribution: The case for cost information asymmetry. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 30, 494–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, R.; Wang, W. Pricing decision of a manufacturer in a dual-channel supply chain with asymmetric information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 278, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, B.; Chen, P. Dual-channel supply chain decisions under asymmetric information with a risk-averse retailer. J. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 257, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Optimal contract design for dual-channel supply chains under information asymmetry. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J. Inducing information transparency: The roles of gray market and dual-channel. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 329, 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Contracting with countervailing incentives under asymmetric cost information in a dual-channel supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 171, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; He, N.; Huang, S. Government penalty provision and contracting with asymmetric quality information in a bioenergy supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 154, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zong, Y.; Liu, X. Cooperative advertising in dual-channel supply chain under asymmetric demand information. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2023, 27, 100–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, R. Closed-loop supply chain decision making and coordination considering channel power structure and information symmetry. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1411248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Wei, J.; Li, Y. Research on investment optimization and coordination of fresh supply chain considering misreporting behavior under blockchain technology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Yang, S.; Ge, B. On the methodological value of big data from the philosophy of complexity science. J. Syst. Sci. 2020, 28, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wu, D.; Xu, H. Signaling or not? The pricing strategy under fairness concerns and cost information asymmetry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 321, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Chen, S.; Huang, S. Observability of retailer demand information acquisition in a dual-channel supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 329, 191–223. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. Research on pricing and information sharing strategies of dual channel green supply chain. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2023, 28, 161–172. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Shen, C.; Su, S. Decision making in green supply chain with manufacturers’ misreporting behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).