Curriculum Material Use in EFL Classrooms: Moderation and Mediation Effects of Teachers’ Beliefs and TPACK

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. TPACK

2.2. Pedagogical Beliefs in English Language Teaching

2.3. Curriculum Material Use Approach in Language Teaching and Learning

2.4. Concept of the Interrelationship Between Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs, TPACK, and Curriculum Material Use

2.5. Conceptual Model

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Instruments

- Describe a specific instance where you effectively combined reading comprehension, technology, and teaching approaches in a classroom lesson. Include details about the content you taught related to reading comprehension, the technology you used, and the teaching approach(es) you implemented.

- Share an example of a specific instance where you effectively applied your teaching approach. Provide details about how you implemented the approach, including examples of activities conducted during reading comprehension sessions.

- Describe a specific instance where you effectively utilized teaching and learning materials by adapting, adopting, or developing them—whether from a textbook, following the curriculum, or creating your own. Include examples of classroom activities where you used these materials for reading comprehension.

3.3. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

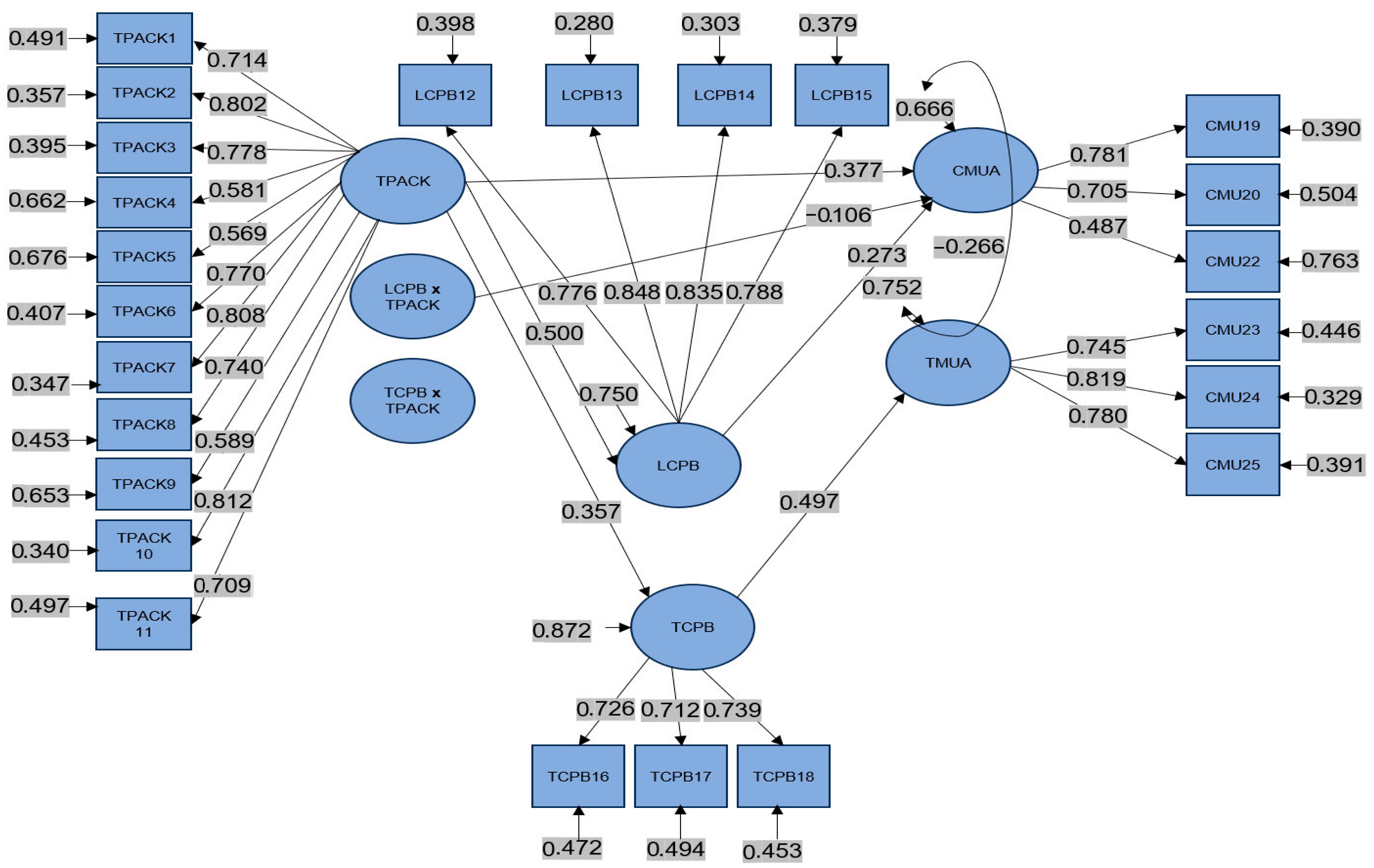

4.3. Mediation and Moderation Structural Model

4.4. Teachers’ TPACK, Pedagogical Beliefs, and Material Use Approach Actual Classroom Practices

4.4.1. Teacher’s TPACK Practice

4.4.2. Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs Practice

4.4.3. Teachers’ Curriculum Material Use Classroom Practices

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, S. S., & Mohammadzadeh, B. (2022). Iraqi Kurdish EFL teachers’ beliefs about technological pedagogical and content knowledge: The role of teacher experience and education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 969195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almunawaroh, N. F., Diem, C. D., & Steklács, J. (2024). EFL teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, and instructional material use: A scale development and validation. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2379696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almunawaroh, N. F., & Steklács, J. (2025). The interplay of secondary EFL teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and pedagogical content knowledge with their instructional material use approach orientation. Heliyon, 11(2), e42065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshumaimeri, Y., & Alharbi, T. (2024). English textbook evaluation: A Saudi EFL teacher’s perspective. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1479735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A., & Rezvani, R. (2021). A tale of three official English textbooks: An evaluation of their horizontal and vertical alignments. Language Related Research, 12(3), 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armin, D. S., & Siregar, A. M. P. (2021). EFL teacher’s pedagogical beliefs in teaching at an Indonesian university. Jurnal Tarbiyah, 28(2), 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artini, L. P., Ratminingsih, N. M., & Padmadewi, N. N. (2018). Project based learning in EFL classes Material development and impact of implementation. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(1), 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakereh, A., Yousofi, N., & Weisi, H. (2019). Critical content analysis of English textbooks used in the Iranian education system: Focusing on ELF features. Issues in Educational Research, 29(4), 1016–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Badjadi, N. E. I. (2020). Learner-centered English language teaching: Premises, practices, and prospects. Journal of Education: Language Learning in Education, 8(1), 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, D. D., Winsor, M. S., Vince Kirwan, J., & Rupnow, T. J. (2020). Searching for the key to knowledge integration: A lens to detect the promotion and use of integrated knowledge. In International perspectives on knowledge integration: Theory, research, and good practice in pre-service teacher and higher education (pp. 59–78). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonmoh, A., & Kulavichian, I. (2023). Exploring Thai EFL pre-service teachers’ technology integration based on SAMR model. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(4), ep457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, M. (2019). Current perspectives on teachers as materials developers: Why, what, and how? RELC Journal, 50(3), 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, B. Y., Nurhadi, K., Novianti, H., & Khansa, M. (2025). EFL teachers’ use of technology in task-based language teaching in teaching reading: Perceptions, variety and intensity. Language Related Research, 16(5), 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çeliker-Ercan, G., & Çubukçu, Z. (2023). Curriculum implementation approaches of secondary school English teachers: A case study. Kastamonu Education Journal, 31(3), 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C. S. (2010). The relationships among Singaporean preservice teachers ’ ICT competencies, pedagogical beliefs and their beliefs on the espoused use of ICT. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 19(3), 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C. S., Chin, C. K., Koh, J. H. L., & Tan, C. L. (2013). Exploring Singaporean Chinese language teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and its relationship to the teachers’ pedagogical beliefs. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 22(4), 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Wei, B., & Wang, X. (2020). Examining the factors that influence high school Chemistry teachers’ use of curriculum materials: From the teachers’ perspective. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 19(6), 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M. (2012). Revisiting Japanese English teachers’ (JTEs) perceptions of communicative, audio-lingual, and grammar translation (yakudoku) activities: Beliefs, practices, and rationales. Asian EFL Journal, 14(2), 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods Research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 13(3), 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, W. (2020). Conceptions of teaching and learning and teaching approach preference: Their change through preservice teacher education program. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1833812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Montijano Cabrera, M. (2014). Textbook use training in EFL teacher education. In Utrecht studies in language and communication (Vol. 27, pp. 267–286). Brill Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depaepe, F., & König, J. (2018). General pedagogical knowledge, self-efficacy and instructional practice: Disentangling their relationship in pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djulia, E., Brata, W. W. W., & Amrizal. (2022). Pre-service Biology students technological pedagogical and content knowledge (TPCK) as prerequisite for professional Biology teacher. In F. Harahap, J. Purba, A. Sutiani, M. Zubir, & S. I. Al Idrus (Eds.), AIP conference proceedings (Vol. 2659). American Institute of Physics Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdu, L., & Dag, F. (2017). Pre-service teachers’ TPACK development and conceptions through a TPACK-based course. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(11), 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. (2017). Task-based language teaching. In S. Loewen, & M. Sato (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of instructed second language (1st ed., pp. 124–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., & Tondeur, J. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs and uses of technology to support 21st-century teaching and learning. In International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 403–418). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, D., Smits, A., & Voogt, J. (2019). Technology integration of pre-service teachers explained by attitudes and beliefs, competency, access, and experience. Computers and Education, 130, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A., Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Peterson, E. (2024). Teacher views of relationships between their teaching practices and beliefs, the school context, and student achievement. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 59(1), 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garton, S., & Graves, K. (2019). Materials use and development. In S. Walsh, & S. Mann (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language teacher education (p. 417). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrettaz, A. M., Engman, M. M., & Matsumoto, Y. (2021). Empirically defining language learning and teaching materials in use through sociomaterial perspectives. Modern Language Journal, 105, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrettaz, A. M., Mathieu, C. S., Lee, S., & Berwick, A. (2022). Materials use in language classrooms: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 55, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed). Pearson Educational Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J. B., & Hofer, M. J. (2011). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in action: A descriptive study of secondary teachers’ curriculum-based, technology-related instructional planning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(3), 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, N. (2010). Issues in materials development and design. In N. Harwood (Ed.), English language teaching materials: Theory and practice (pp. 3–32). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., & Levin, B. B. (2008). Match or mismatch? How congruent are the beliefs of teacher candidates, cooperating teachers, and university-based teacher educators? Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(4), 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B. H., & Seidel, K. (2014). Measuring teachers’ beliefs for what purpose? In International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 106–127). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). A cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichebah, A. (2020). Beliefs on english language teaching effectiveness in Moroccan higher education. In English language teaching in Moroccan higher education (pp. 123–141). Springer Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmehr, A., Davari, H., & Erfani, S. M. (2011). The application of organizers as an efficient technique in ESP textbooks development. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 1(4), 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, T. (2024). The influence of pedagogical and epistemological beliefs on preservice teachers’ technology acceptance in Turkey: A structural equation modeling. Croatian Journal of Education, 26(2), 607–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Akcaoglu, M., & Rosenberg, J. M. (2016). The technological pedagogical content knowledge 20 framework for teachers and teacher educators. In M. R. Panigrahi (Ed.), Resource book on ICT integrated teacher education (pp. 20–30). Commonwealth Educational Media Centre for Asia. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C., Wang, Q., & Huang, X. (2022). The differential interplay of TPACK, teacher beliefs, school culture and professional development with the nature of in-service EFL teachers’ technology adoption. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(5), 1389–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larenas, C. D., Hernandez, P. A., & Navarrete, M. O. (2015). A case study on EFL teachers ’ beliefs about the teaching and learning of English in public Education. Porta Linguarum, 23, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. (2021). Disentangling teachers’ enactment of materials: A case study of two language teachers in higher education in China. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 29(3), 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Harfitt, G. (2018). Understanding language teachers’ enactment of content through the use of centralized curriculum materials. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 46(5), 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., & He, L. (2017, December 7–9). Relationships of TPACK and beliefs of primary and secondary teachers in China. 2017 International Conference of Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT) (pp. 32–35), Osaka, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S. C., & Vieira, F. (2020). The role of textbooks for promoting autonomy in English learning. Revista Brasileira de Linguistica Aplicada, 20(1), 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Lin, C.-H., & Zhang, D. (2017). Pedagogical beliefs and attitudes toward information and communication technology: A survey of teachers of English as a foreign language in China. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(8), 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maijala, M. (2020). Pre-service language teachers’ reflections and initial experiences on the use of textbooks in classroom practice. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(2), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. I., Díaz Lara, G., & Whitney, C. R. (2025). The role of teacher beliefs in teacher learning and practice: Implications for meeting the needs of English learners emergent bilinguals. Language and Education, 39(3), 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maru, M. G., Pikirang, C. C., Ratu, D. M., & Tuna, J. R. (2021). The integration of ICT in ELT practices: The study on teachers’ perspective in new normal era. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 15(22), 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuhara, H. (2022). Approaches to materials adaptation. In J. Norton, & H. Buchanan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of materials development for language teaching (pp. 277–289). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazgon, J., & Stefanc, D. (2012). Importance of the various characteristics of educational materials: Different opinions, different perspectives. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 11(3), 174–188. [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie, A. M. R., & Mather, M. (2006). Reification of instructional materials as part of the process of developing problem-based practices in Mathematics education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12(4), 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertala, P. (2019). Teachers’ beliefs about technology integration in early childhood education: A meta-ethnographical synthesis of qualitative research. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukminin, A., & Habibi, A. (2020). Technology in the classroom: EFL teachers’technological pedagogical and content knowledge. Informatologia, 53(1–2), 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, N., Nafissi, Z., Estaji, M., Marandi, S. S., & Wang, S. (2019). Evaluating novice and experienced EFL teachers’ perceived TPACK for their professional development. Cogent Education, 6, 1632010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, M. (2015). Textbooks: Impact on curriculum. In Encyclopedia of science education (pp. 1070–1073). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Nurwahidah, N., Sulfasyah, S., & Rukli, R. (2023). Investigating grade five teachers’ integration of technology in teaching reading comprehension using the TPACK framework. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 14(4), 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxasana, S. E., Chen, J., & Du, X. (2023). Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs in a project-based learning school in South Africa. Education Sciences, 13(2), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfan, S. N., Noori, A. Q., & Akramy, S. A. (2021). Afghan EFL instructors’ perceptions of English textbooks. Heliyon, 7(11), e08340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramerta, I. G. P. A., Pramawati, A. A. I. Y., Widhiasih, L. K. S., Mas, L. A. M. G. D., & Andari, K. A. M. (2025). Tailoring reading courses to student needs: A pathway to effective curriculum and teaching strategies. Educational Process: International Journal, 15, e2025165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasojo, L. D., Habibi, A., Mukminin, A., & Yaakob, M. F. M. (2020). Domains of technological pedagogical and content knowledge: Factor analysis of indonesian in-service EFL teachers. International Journal of Instruction, 13(4), 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. C. (2014). The ELT textbook. In S. Garton, & K. Graves (Eds.), International perspectives on materials in ELT (pp. 19–36). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J. M., & Koehler, M. J. (2015). Context and technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A systematic review. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 47(3), 186–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. M., & Castro, R. D. R. (2021). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in action: Application of learning in the classroom by pre-service teachers (PST). Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 3(1), 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D. A., Baran, E., Thompson, A. D., Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Shin, T. (2009). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): The development and validation of an assessment for preservice teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(2), 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P. A., Hong, J. Y., & Francis, D. C. (2020). Teachers’ goals, beliefs, emotions, and identity development: Investigating complexities in the profession (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawer, S. F. (2010). Classroom-level curriculum development: EFL teachers as curriculum-developers, curriculum-makers and curriculum-transmitter. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M. F., Cayton, C., Walkington, C., & Funsch, A. (2020). An analysis of secondary Mathematics textbooks with regard to technology integration. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 51(3), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. (2021). Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 9(1), 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledege and teaching: Foundation of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamdianita, S., & Cahyono, B. Y. (2021). The EFL pre-service teachers’ experiences and challenges in designing teaching materials using TPACK framework. Studies in English Language and Education, 8(2), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tergujeff, E. (2015). Good servants but poor masters: On the important role of textbooks in teaching English pronunciation. Second Language Learning and Teaching, 24, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B. (2022). The discipline of materials development. In J. Norton, & H. Buchanan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of materials development for language teaching. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The complete guide to the theory and practice of materials development for language learning. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, J.-J., Cheng, Y.-S., & Lin, C.-C. (2011). Unraveling in-service EFL teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Asia TEFL, 8(2), 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Van Canh, L. (2018). A critical analysis of moral values in Vietnam-produced EFL textbooks for upper secondary schools. In English language education (Vol. 9, pp. 111–129). Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T., Chai, C.-S., & Wang, L.-J. (2022). Exploring secondary school teachers’ TPACK for video-based flipped learning: The role of pedagogical beliefs. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 8793–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Durak, H. (2021). Modeling of relations between K-12 teachers’ TPACK levels and their technology integration self-efficacy, technology literacy levels, attitudes toward technology and usage objectives of social networks. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(7), 1136–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohrabi, M., Sabouri, H., & Behroozian, R. (2012). An evaluation of merits and demerits of Iranian first year high school English textbook. English Language Teaching, 5(8), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| TPACK |

| |

| Pedagogical Beliefs | LCPB |

|

| TCPB |

| |

| Material Use | Constructivist approach |

|

| Transmissive approach |

|

| M (SD) | CR | α | AVE | TPACK | LCPB | TCPB | CMUA | TMUA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPACK | 4.02 (0.43) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.52 | 1 | ||||

| LCPB | 4.43 (0.49) | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.464 ** | 1 | |||

| TCPB | 3.38 (0.92) | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.296 ** | 0.099 | 1 | ||

| CMUA | 3.82 (0.59) | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.384 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.198 ** | 1 | |

| TMUA | 3.18 (0.73) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.166 ** | 0.014 | 0.386 ** | −0.084 | 1 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Standardized Regression (β) | Sig | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Mediator | Moderator | Outcome | ||

| TPACK | CMUA | 0.377 ** | <0.01 | ||

| TPACK | TMUA | 0.002 | >0.05 | ||

| TPACK | LCPB | 0.500 ** | <0.01 | ||

| TPACK | TCPB | 0.357 ** | <0.01 | ||

| LCPB | CMUA | 0.273 ** | <0.01 | ||

| TCPB | TMUA | 0.497 ** | <0.01 | ||

| TPACK | LCPB | CMUA | 0.136 ** | <0.01 | |

| TPACK | TCPB | TMUA | 0.177 ** | <0.01 | |

| TPACK | LCPB | CMUA | 0.106 ** | <0.01 | |

| TPACK | TCPB | TMUA | 0.021 | >0.05 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almunawaroh, N.F.; Steklács, J. Curriculum Material Use in EFL Classrooms: Moderation and Mediation Effects of Teachers’ Beliefs and TPACK. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121647

Almunawaroh NF, Steklács J. Curriculum Material Use in EFL Classrooms: Moderation and Mediation Effects of Teachers’ Beliefs and TPACK. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121647

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmunawaroh, Nurul Fitriyah, and János Steklács. 2025. "Curriculum Material Use in EFL Classrooms: Moderation and Mediation Effects of Teachers’ Beliefs and TPACK" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121647

APA StyleAlmunawaroh, N. F., & Steklács, J. (2025). Curriculum Material Use in EFL Classrooms: Moderation and Mediation Effects of Teachers’ Beliefs and TPACK. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121647