3. Methodology

3.1. Participant Selection

The data were gathered from 59 participants from two different corpora of sociolinguistic interviews conducted in different neighborhoods in Lima, as part of the research project

Language Change as a Result of Andean Migration to Lima, Peru begun in 1999 by Klee and Caravedo. Participants were divided into three different migrant generations. First generation participants were individuals born in an Andean region of Peru who migrated to Lima after the age of seven. Second generation migrants were those who were born in Lima and who had at least one first generation parent. Third generation migrants were also born in Lima and had at least one first generation grandparent and second generation parent. “Classic” Limeños, or those born in Lima who did not have migrant parentage for at least three generations were labeled as the 4th generation. The first corpus was gathered in 1999–2002 in both traditional Limeño neighborhoods and more established migrant settlements by fieldworkers who were familiar with or resided in the area of the city in which they conducted interviews. In all, the first corpus comprised 82 participants, of which 20 were from traditional Limeño neighborhoods, 62 were from older migrant settlements. The second corpus consisted of 26 interviews gathered in 2012–2013 from the established migrant neighborhood of Los Olivos by a fieldworker from the community. Los Olivos is unique among other migrant neighborhoods because it is the most affluent of these neighborhoods in the northern metropolitan area of Lima and it is made up of several generations of immigrants. The overall population of Los Olivos is 365,921 (

INEI, 2014) and is relatively young with a mean age of around 29 years old. Unlike the majority of other migrant settlements, residents of Los Olivos enjoy more upward social mobility and more educational opportunities. Overall, 21% of Los Olivos is considered to be upper-middle or middle class (

Alcázar & Andrade, 2008), a high number for a district made up of primarily migrants, although there still are notable rates of poverty (37%) among first generation Andean migrants on the outskirts.

A subset of the corpus was analyzed to balance the number of participants by generations. Fifteen participants were selected from generations one, two, and three as well as 14 classic Limeños, labeled “fourth generation.” The social variables taken into account include Migrant Generation, Family Origin, Neighborhood, Biological Sex, and Education. There is some degree of correlation between migrant generation and some of the other social variables. In terms of family origin, all first-generation (G1) participants are of Andean origin; second-generation (G2) participants are either of Andean or mixed origin; third-generation (G3) participants represent all three categories—Andean (4), mixed (6), and non-Andean (5); and, fourth-generation (G4) participants are exclusively of non-Andean origin. With respect to neighborhood distribution across migrant generations, all G1 participants reside in shantytowns. Among G2 participants, 11 live in shantytowns and 4 in Los Olivos. In G3, the majority (10) reside in Los Olivos, while 3 live in shantytowns, and 2 in established neighborhoods. In G4, 13 participants live in established neighborhoods and 1 in Los Olivos. Efforts were made to balance gender representation; however, G4 includes a disproportionate number of women (11) compared to men (3). Regarding educational attainment, G1 is the only generation with participants (8) who have only primary education, and none who have received technical or higher education. See

Table A1 in the

Appendix A for the social characteristics by migrant generation and

Table A2 in the

Appendix A for the social characteristics of each participant.

3.2. Data Measurement and Instruments

The larger Lima corpus was coded impressionistically for [s], [h] and Ø in coda position, in both word-internal ([’mues.tra]) and word final phonetic contexts ([sa. ’li.mos]), as has been done in the vast majority of similar studies on Spanish /s/ variation, primarily due to the perceptual salience between categories (e.g.,

Cepeda, 1990;

Caravedo, 1990;

Hundley, 1983;

Klee & Caravedo, 2006; among many others). Consecutive orthographic representations of /s/ (e.g., {los sordos}) and instances of [h] followed by [x] (e.g., [loh.’xu̯e.ɣ̞os]) were excluded. For each speaker, 200 tokens were coded after the 10 minute mark in the interview, when the speakers were more acclimated and comfortable with the interviewer and the overall conversation, for an overall total of 8798 tokens

2 from 44 speakers. One of the difficulties coding for /s/ is how quickly background noise can alter or overlap the acoustic signal, making it impossible at times to accurately code /s/. Thus, in cases where background noise was too high, the coders skipped forward to where there was no more background interference in the recordings and continued to code. Files that had too much ambient noise throughout were excluded from the sample size. After being coded, two linguists impressionistically verified the coding. Afterwards, for purposes of inter-rater reliability, a third linguist, using Praat (

Boersma & Weenink, 2023) acoustically verified a random sample of 589 tokens to compare to the impressionistic results. The overall rate of agreement between the impressionistic and acoustic verifications regarding the classification of each instance of /s/ (i.e., [s], [h] or elision) was 77.6%.

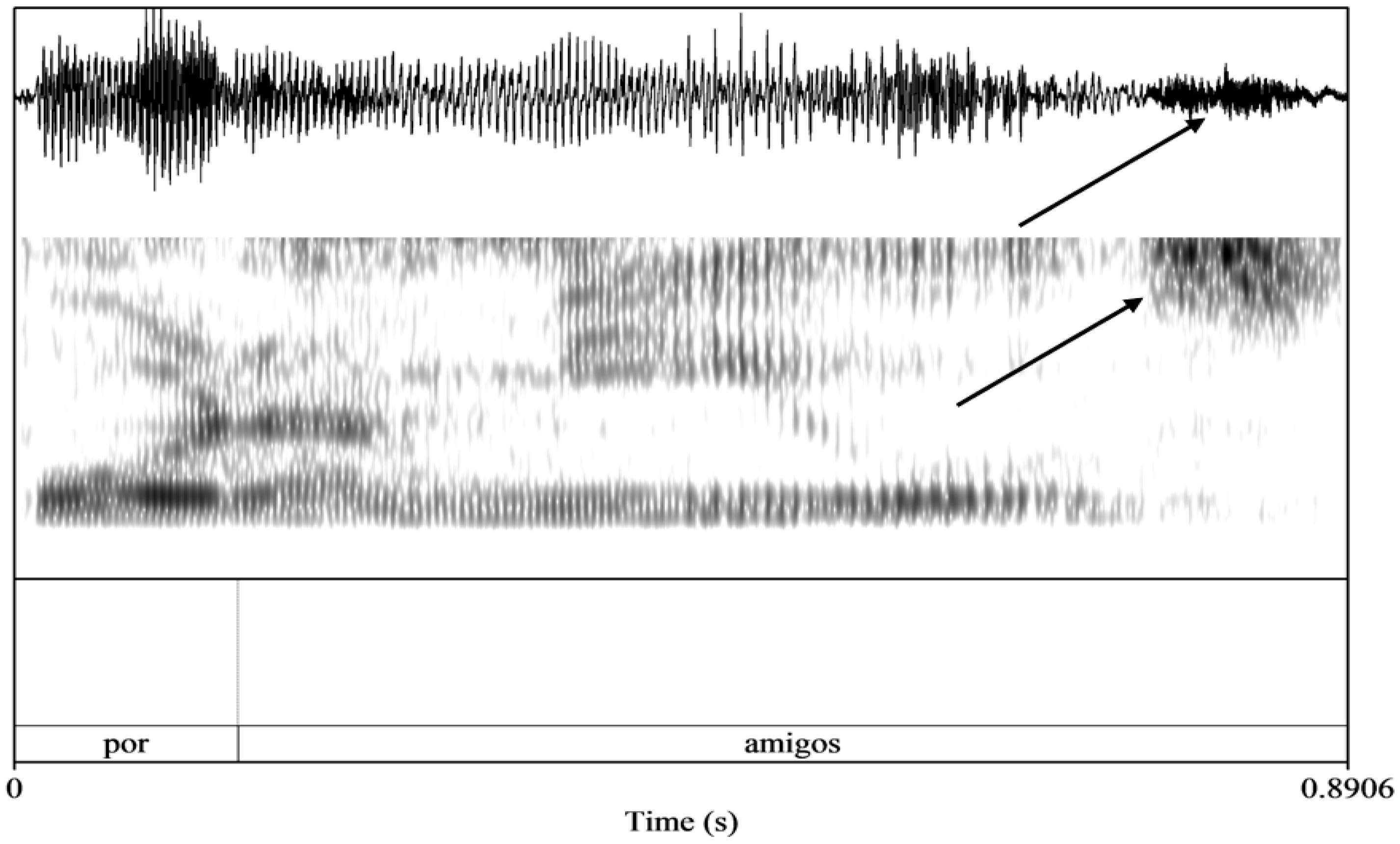

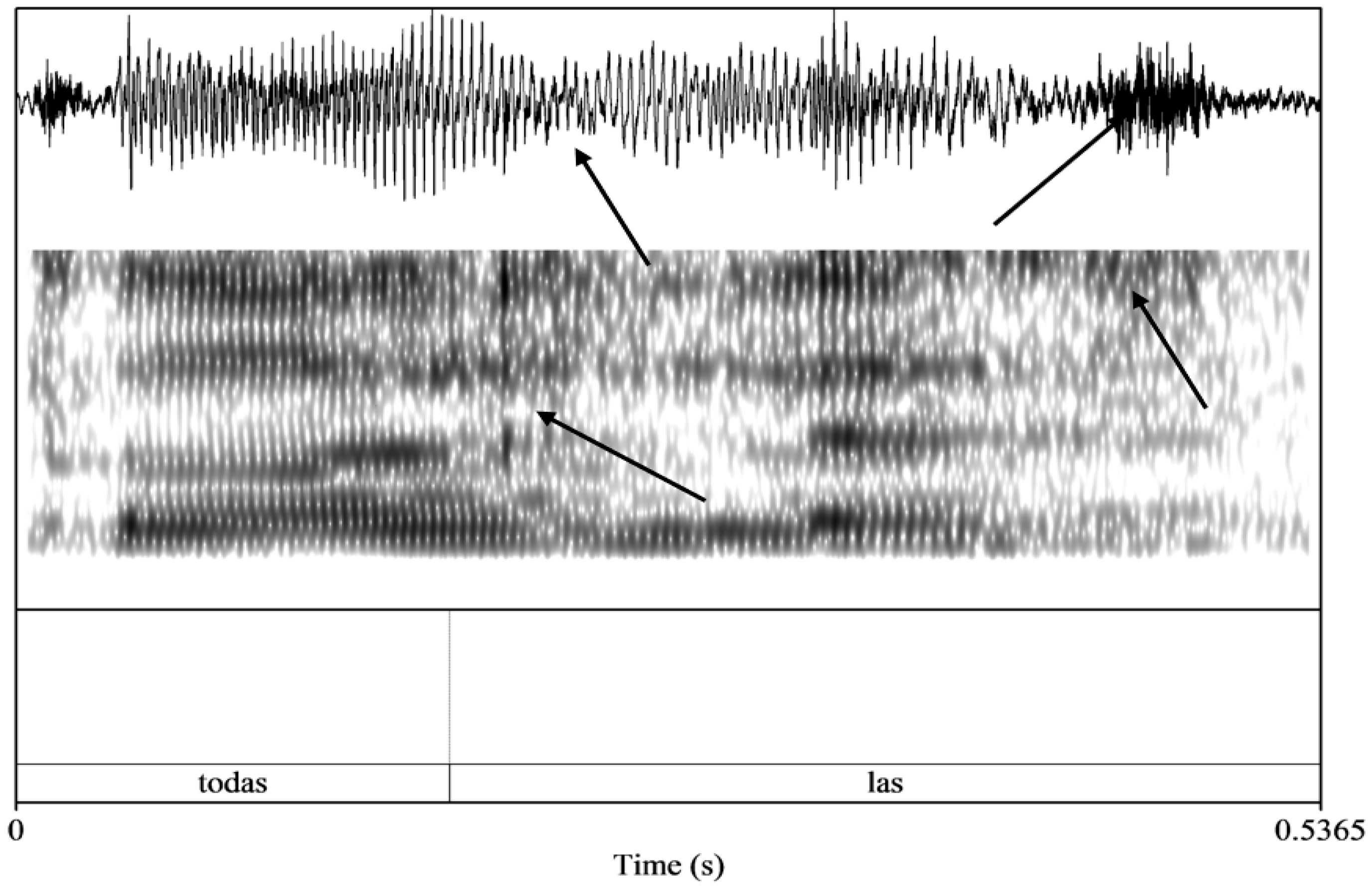

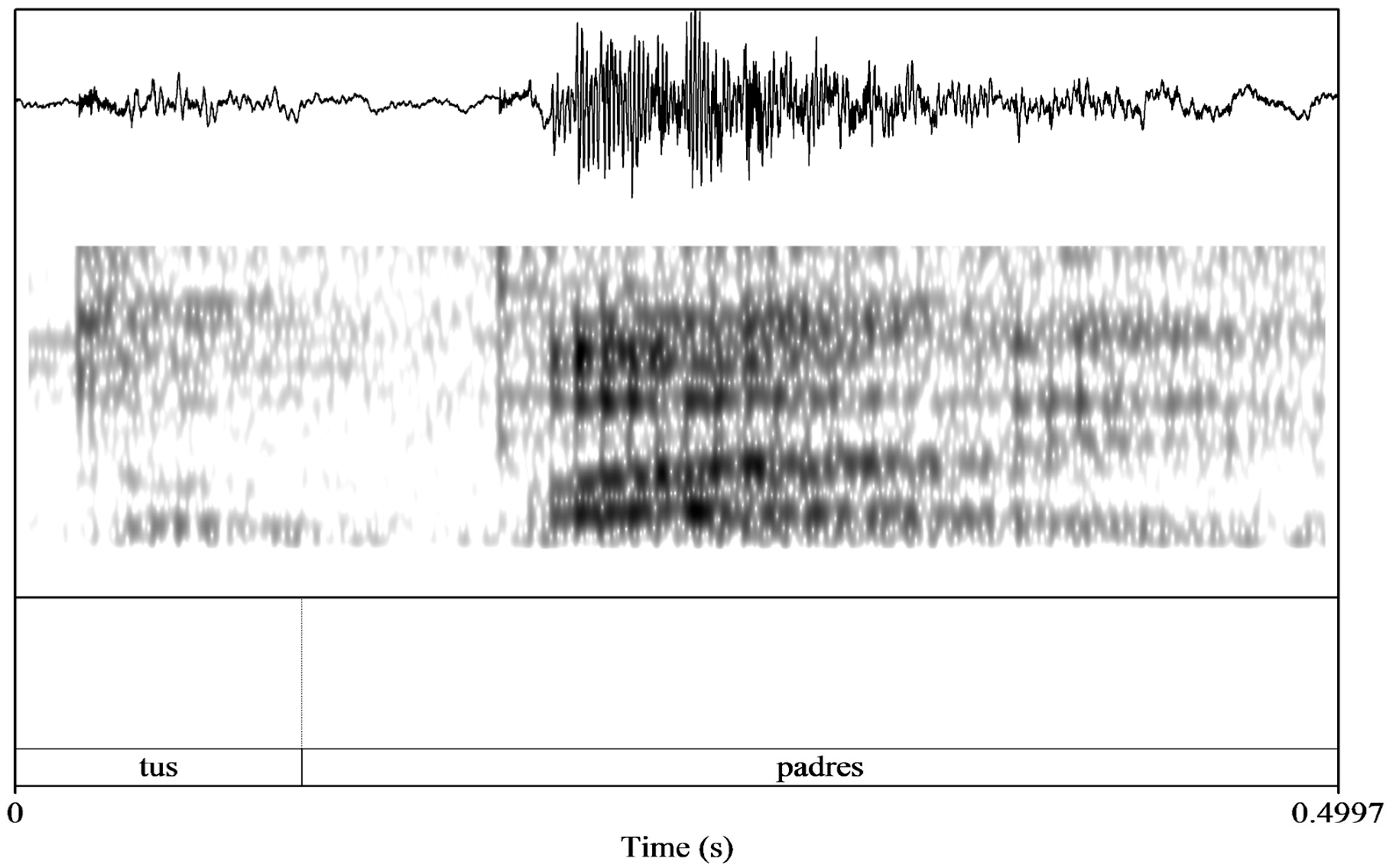

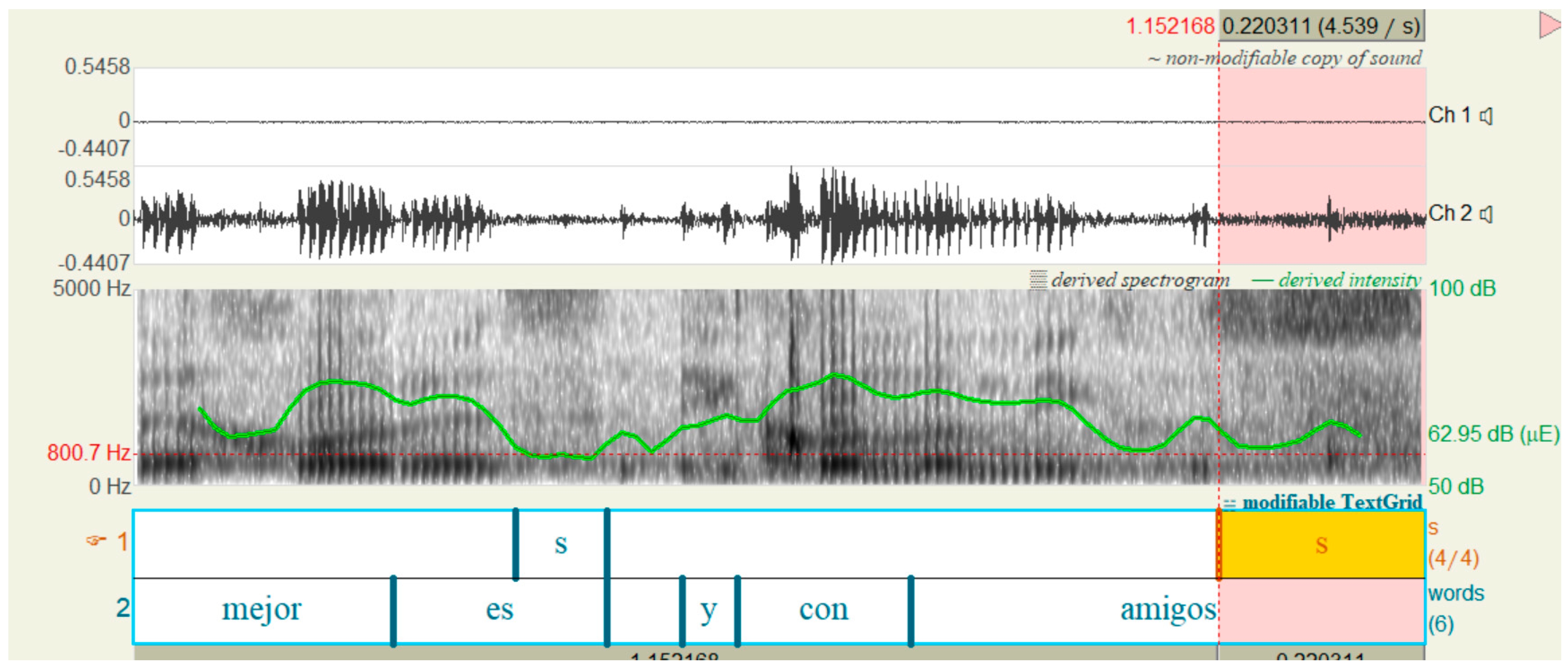

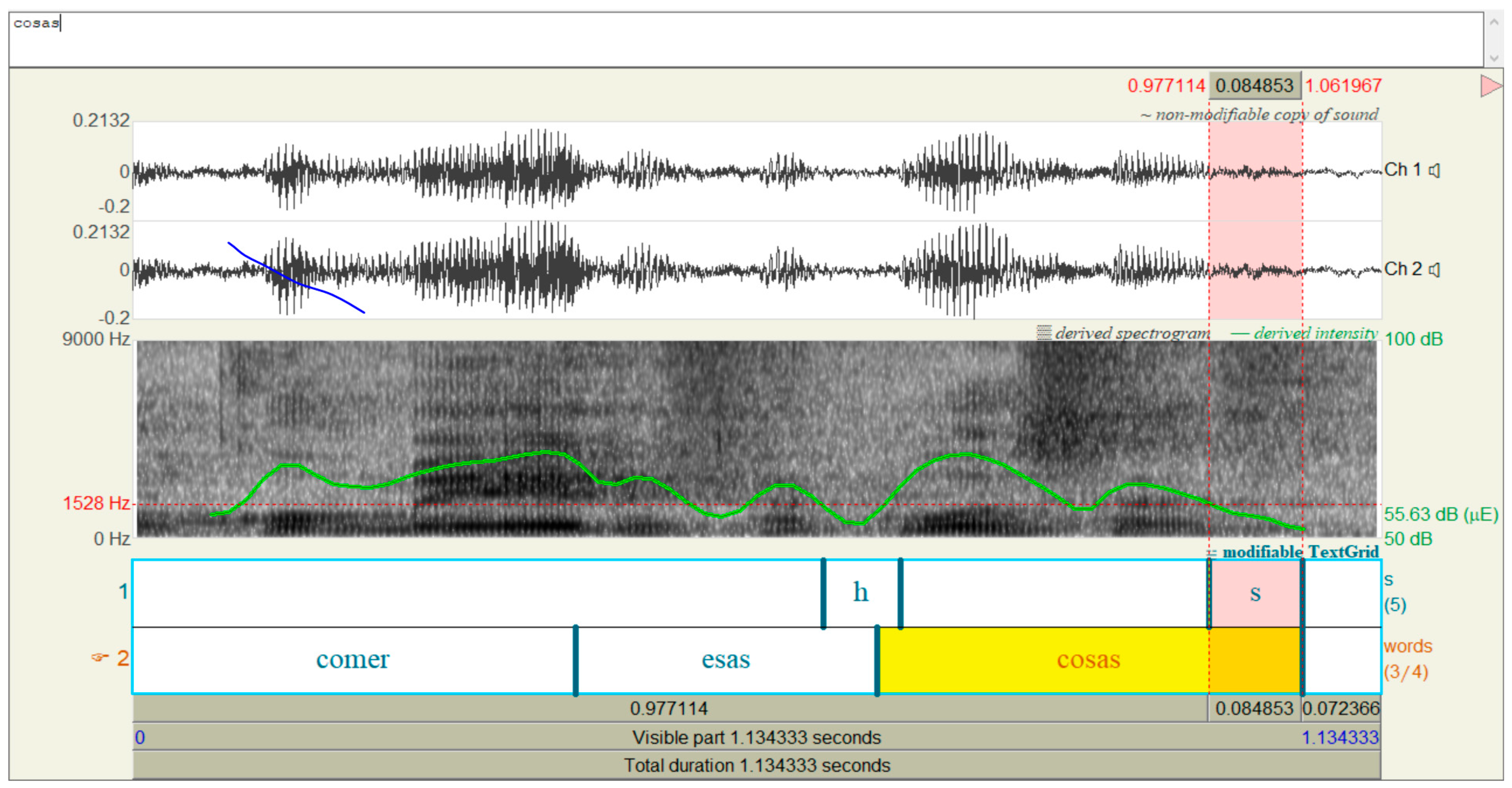

The Los Olivos data were coded acoustically using Praat (

Boersma & Weenink, 2023) for the same three allophonic variants of /s/ in the same phonetic contexts as the larger Lima corpus. 201 tokens of /s/ were coded per speaker after the 10 minute mark of each interview for an overall total of 3015 tokens from 15 speakers. Several methods were used to classify /s/ as either a sibilant, aspirated, or elided. First, the sibilant was considered to be present when aperiodicity was observed in waveform along with turbulence in the spectrogram. Aspiration was determined based on the presence of glottalized turbulence, or glottalization, in the spectrogram. The turbulence that is indicative of sibilants differs from that of [h] principally along the lines of how it is distributed in the spectrogram as a result of the different manners of articulation of each segment. When [s] is produced, generally, the blade of the tongue approximates or makes contact with the alveolar ridge, resulting in greater constriction of the airflow from the lungs. As a consequence, especially in the upper limits of the spectrogram, a great deal of strong and strident turbulence is observable. The aspirated [h] is articulated with a notably lesser amount of oral constriction and thus does not result in the same strong and strident turbulence that is characteristic of [s]. Turbulence characteristic of [h] is weaker and more evenly distributed throughout the observable spectrogram. Tokens were coded as elided if there was no visible evidence of turbulence or glottalization and no aperiodicity in the waveform. These criteria were also used during the acoustic verification of the larger corpus.

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate how [s], [h] and Ø were acoustically verified.

Figure 1 is a case of [s] and the arrows indicate the presence of strident turbulence in the spectrogram and aperiodic waves in the waveform. In

Figure 2, [h] is observed, with the arrows denoting the spectral turbulence and aperiodicity typical of the voiceless glottal fricative.

Figure 3 is an example of elision with no observable evidence of sibilancy or aspiration at the end of the word “gratis”.

Even though tokens were grouped into three distinct categories, it must be noted that phonetic variation in each category was observed in both corpora. In addition to the [s], [h], and elision the following allophones were also observed: [ɦ] (voiced glottal fricative, i.e., [’miɦ.mo]), [x] (voiceless velar fricative, i.e., [’max.ke]), [z] (voiced alveolar fricative, i.e., [’miz.mo]), [ʔ] (glottal stop, i.e., [’ko.saʔ],), and [θ] (voiceless interdental fricative, i.e., [miθ.’ko.sas]), and [ɸ] (voiceless bilabial fricative, i.e., [loɸ. ’po.βɾes]). The following allophones were categorized as [s]: [s], [s̺], [θ], [ʃ], [z], [ˢ] (weakened voiceless alveolar fricative), and [z] (weakened voiced alveolar fricative). The following segments were categorized as [h]: [h], [ɦ], [ɸ], [h] (weakened voiceless glottal fricative), and [ɦ] (weakened voiced glottal fricative). It must be noted that in instances of [z] and [ɦ], because these segments are generally fully voiced, the aperiodic oscillations normally present in voiceless productions were frequently absent in the waveform, and as a result, the spectrographic turbulence patterns were used to confirm their presence. Elision occurred where there was no evidence of [s] or [h] or in cases where /s/ was realized as a glottal stop. In all, 11,813 tokens of /s/ were coded.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for the social and linguistic variables. The analysis of the social variables included a total of 11,813 /s/ tokens, comprising both word-internal and word-final positions. Word-internal tokens were included in the analysis of social variables as the following segment in that position is always a consonant. Previous studies have shown that coda /s/ weakening originates in preconsonantal environments both diachronically and synchronically (

Núñez-Méndez, 2022). To determine whether the degree of /s/ weakening changes across migrant generations, preconsonantal environments, both internal and final, were particularly important to include in the analysis. In contrast, the analysis of the linguistic variables focused exclusively on word-final /s/, in line with previous literature (see

Section 2.1.2). This restriction is methodologically justified, as only in word-final position can coda /s/ be followed by a vowel or a pause, segments that have been shown to significantly condition the realization of coda /s/. Limiting the analysis to this position allows for a more precise examination of the phonological factors influencing /s/ weakening.

Originally we used a proportional-odds (ordinal regression) mixed effects model of the social and linguistic variables separately. We selected this approach because although /s/ was coded categorically in our study, phonetically it exists along an acoustic continuum. Within the framework of a proportional odds model, the researcher is able to model an ordered, or categorically coded, dependent variable while assuming that there is variation and continuity with categories. The model accomplishes this by restricting its overall complexity based on the assumption that the categories respond in similar manners to changes in the independent variables. The model assumes that for /s/, the true underlying acoustic value, represented as ψ, can only be captured by way of observable ordinal categories. In other words, the sibilant undergoes weakening along an assumed continuum within its category before it is considered [h]. The aspirated variant must also weaken before being considered elided. An analysis that makes the overarching assumption that [s], [h], and Ø are unordered categories, does not take into account the natural ordering of the response.

One of the reviewers raised a concern regarding our use of ordinal regression, noting that while the model appropriately captures the ordered nature of /s/ variants in terms of articulatory constriction, it may not reflect the indexical social meanings associated with these variants. Specifically, the reviewer pointed out that aspiration [h], despite being less constricted than sibilance [s], may carry greater prestige due to its association with middle-class Limeño Spanish. We acknowledge that the relative social prestige of [s] versus [h] in Lima remains an open empirical question. Nevertheless, we took this critique seriously and evaluated the suitability of the ordinal model. Our diagnostics revealed that the ordinal regression model applied to social variables exhibited poor fit and limited explanatory power. In contrast, the ordinal model for linguistic variables (e.g., phonological environment) demonstrated strong predictive performance, suggesting that ordering is more appropriate in that domain. Consequently, we adopted a multinomial regression with mixed effects for the analysis of social factors, although we begin our analysis with a univariable model with just migrant generation as it is the variable of interest. We then see how those results change in a multivariable model with the other social factors. All computations were performed using R version 4.5.1 (13 June 2025) (

R Core Team, 2025). We tested multiple model configurations to identify the best-fitting structure, including one that combined migrant generation and family origin to address collinearity, as suggested by the referee. The final model was selected based on its superior performance across several metrics—Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and residual deviance—as well as its predictive accuracy. These diagnostics collectively support the robustness of the model presented in the results section and its ability to capture the sociolinguistic patterns in the data more effectively than alternative approaches.

The goal of the current study, as is the case with many sociolinguistic investigations, was to generalize to the extent possible for a larger population in Lima. Therefore, random effects were studied to better comprehend the variability of the populations used. Thus, the effect of individual variation on the data is taken into account by including speaker as a random effect in the model.

Analysis of the Linguistic Variables

For the linguistic variables, we focused on factors that have been shown to be relevant in previous studies cited in the review of the literature section of this paper:

Position of syllable-final /s/ in the word: internal or final. For the analysis of linguistic factors that condition variation, we focused only on /s/ in word final position.

Following segment, coded as vowel, pause, voiceless consonant or voiced consonant.

Preceding segment. For the analysis only two categories were included (i.e., high vowels and non-high vowels) as there were only 143 consonants in preceding position out of 11,813 tokens.

Prosodic stress of the syllable containing /s/, coded as tonic or atonic.

Word length, coded as monosyllabic or polysyllabic.

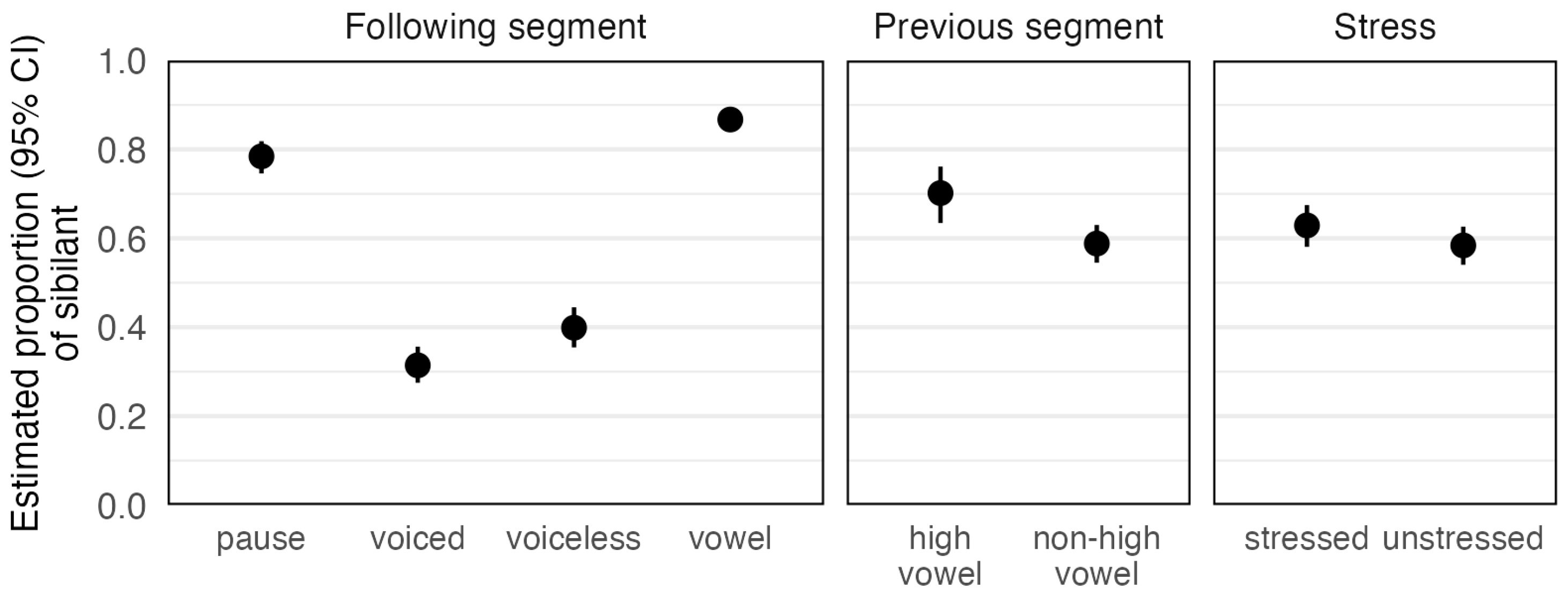

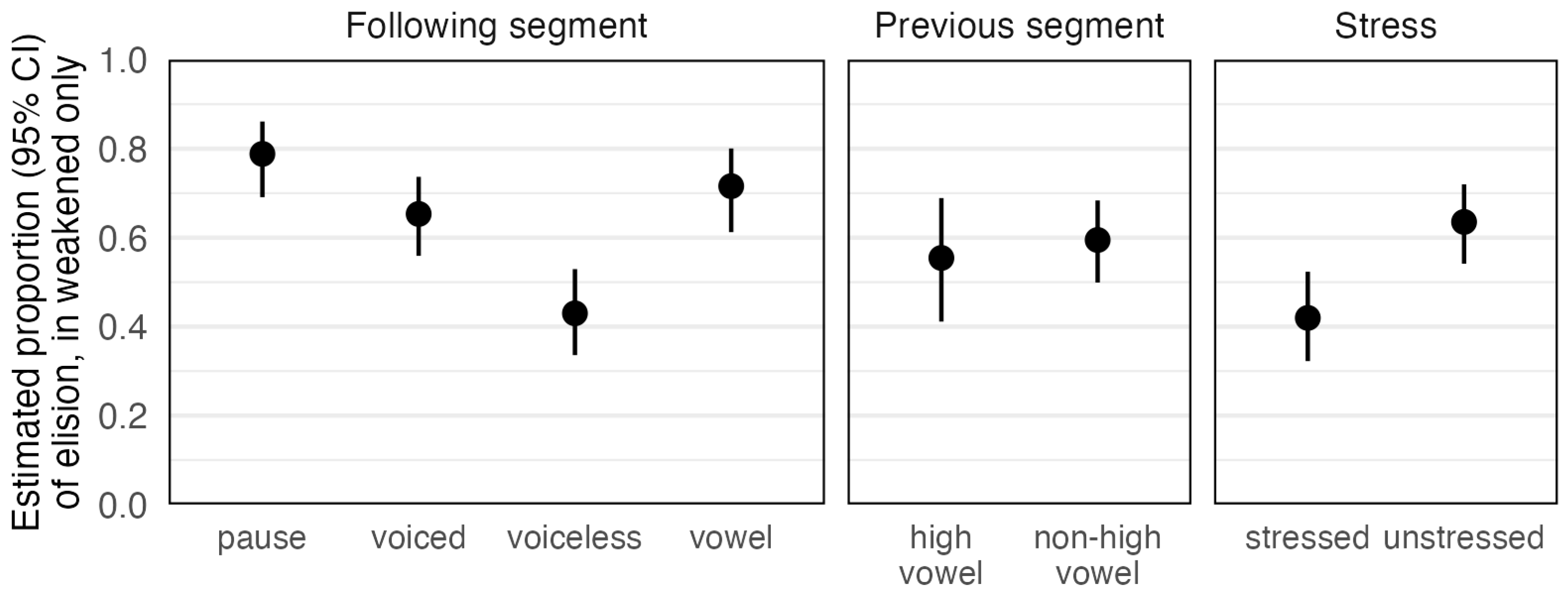

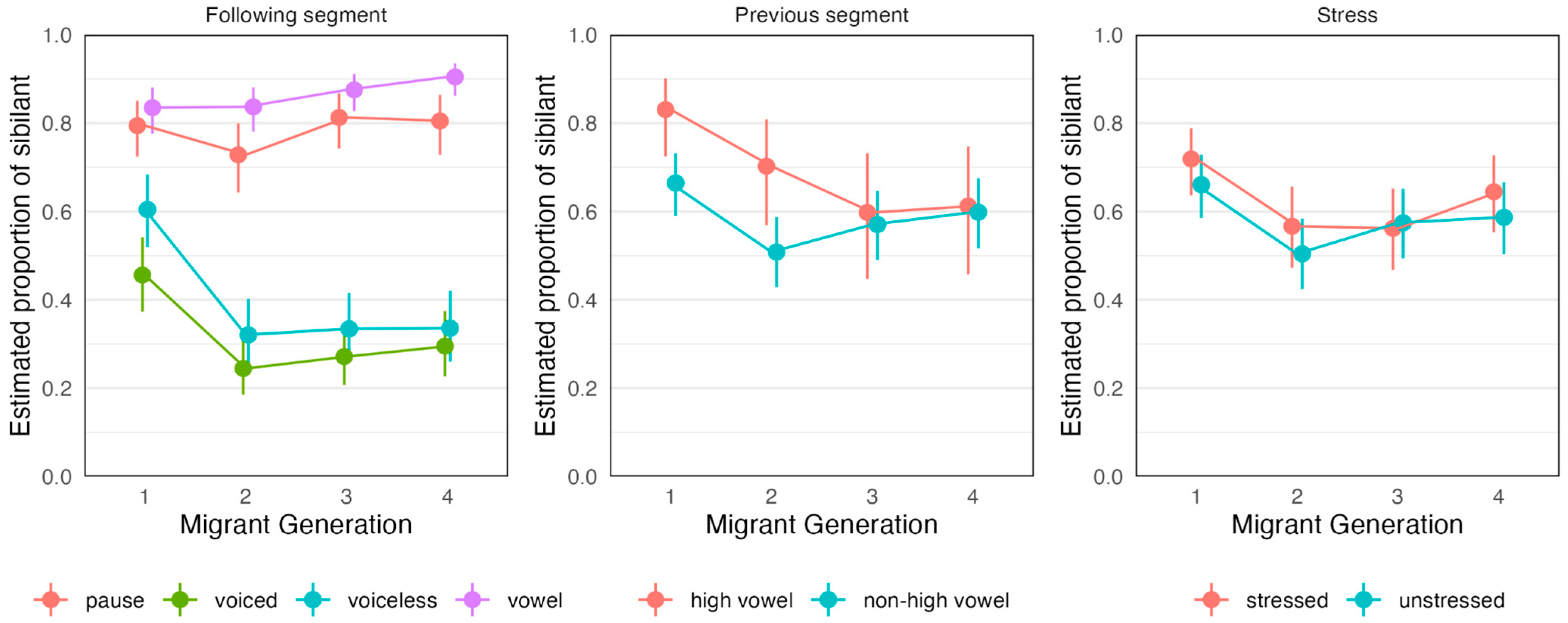

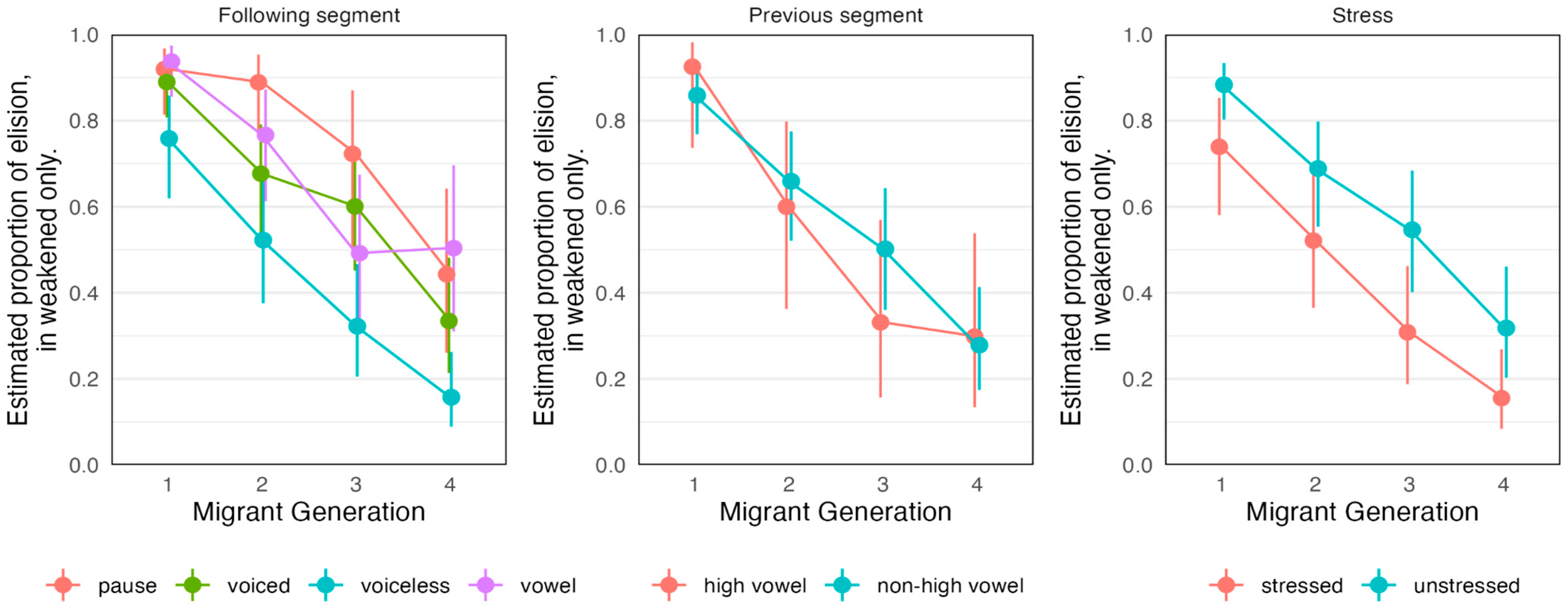

Three separate models were developed to compare the production of the four migrant generations: (1) the first was an ordinal model with all three variants, i.e., [s], [h], and Ø; (2) the second was a logistic model comparing the production of /s/ as a sibilant vs. weakened variants; and (3) the third was a logistic model comparing aspiration and elision. Each of the three models was fit for word final coda /s/ by migrant generation. A random effect for speaker was included. To test the fit of each model, estimated marginal means were computed for the probability of each response for each variable. Averages, weighted by the proportions present in the data, were used over the predicted values of other variables. Although—as mentioned above—the ordinal model demonstrated good predictive performance, the two logistic models, one of the sibilant vs. the weakened variants and the other comparing aspiration and elision, demonstrated the best fit and are presented below. Two additional logistic models were developed to determine whether the effects of the linguistic constraints were consistent across the four generations.

5. Discussion

The phenomenon of /s/ weakening is linked to the long-term history of linguistic change in the phonological distinctions among sibilants in Spanish, a gradual process that has developed differently across diverse Spanish-speaking communities. In the present analysis, gradual linguistic change is evident in apparent time, seen in differences across migrant generations. However, linguistic change in Lima involves not only the temporal dimension but also the spatial one, occurring through the interaction of both dimensions. This requires a reevaluation of the traditional approach to linguistic variation in Peru, which assumes that space is a fixed entity. Instead, we have adopted a dynamic view of space, as developed in humanistic geography, where speaker mobility through large-scale migration has brought together varieties of Spanish that were previously separated. This dynamic view of space facilitates the understanding of linguistic diversity and language change by taking into account the significant influence of population movements, which have resulted in contact between different varieties of Spanish and given rise to a variety of linguistic changes. This concept is central to the Project

Language Change as a Result of Andean Migration to Lima, Peru, which has found that migration of Andean settlers to the capital is a significant driver of sociolinguistic change, as demonstrated in studies of other linguistic phenomena (

Caravedo & Klee, 2012;

Klee & Caravedo, 2005,

2006,

2020;

Klee et al., 2011,

2021).

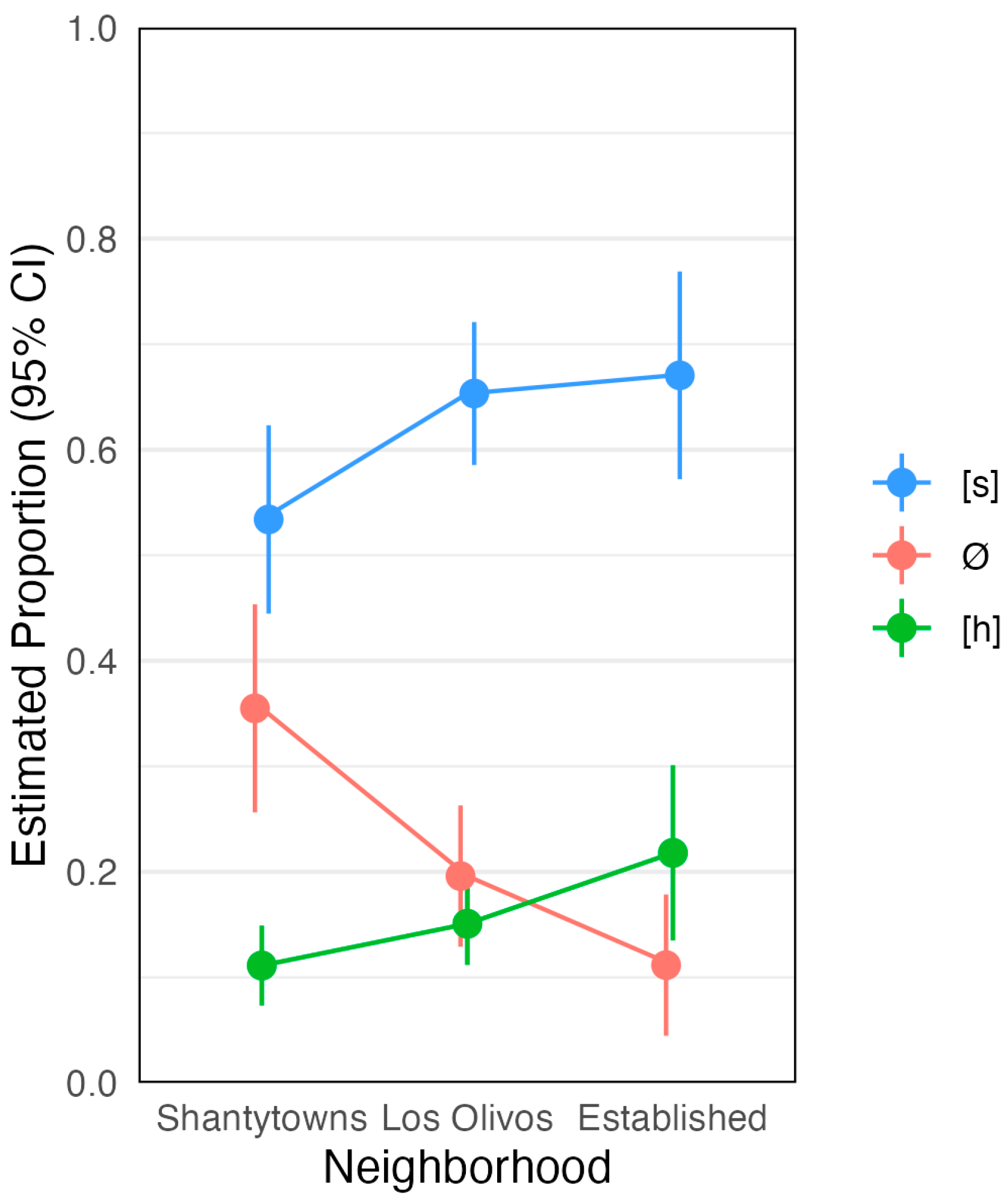

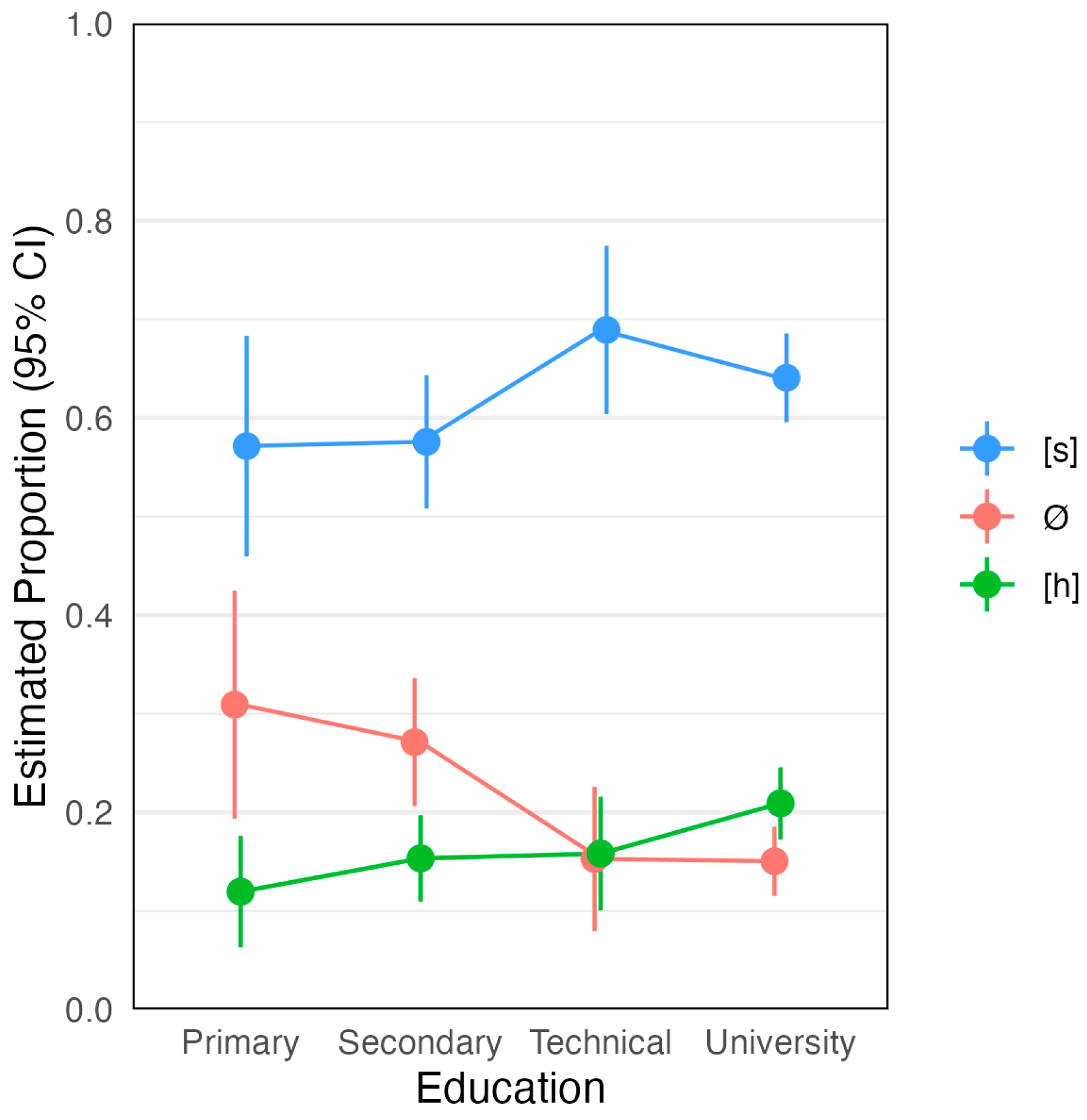

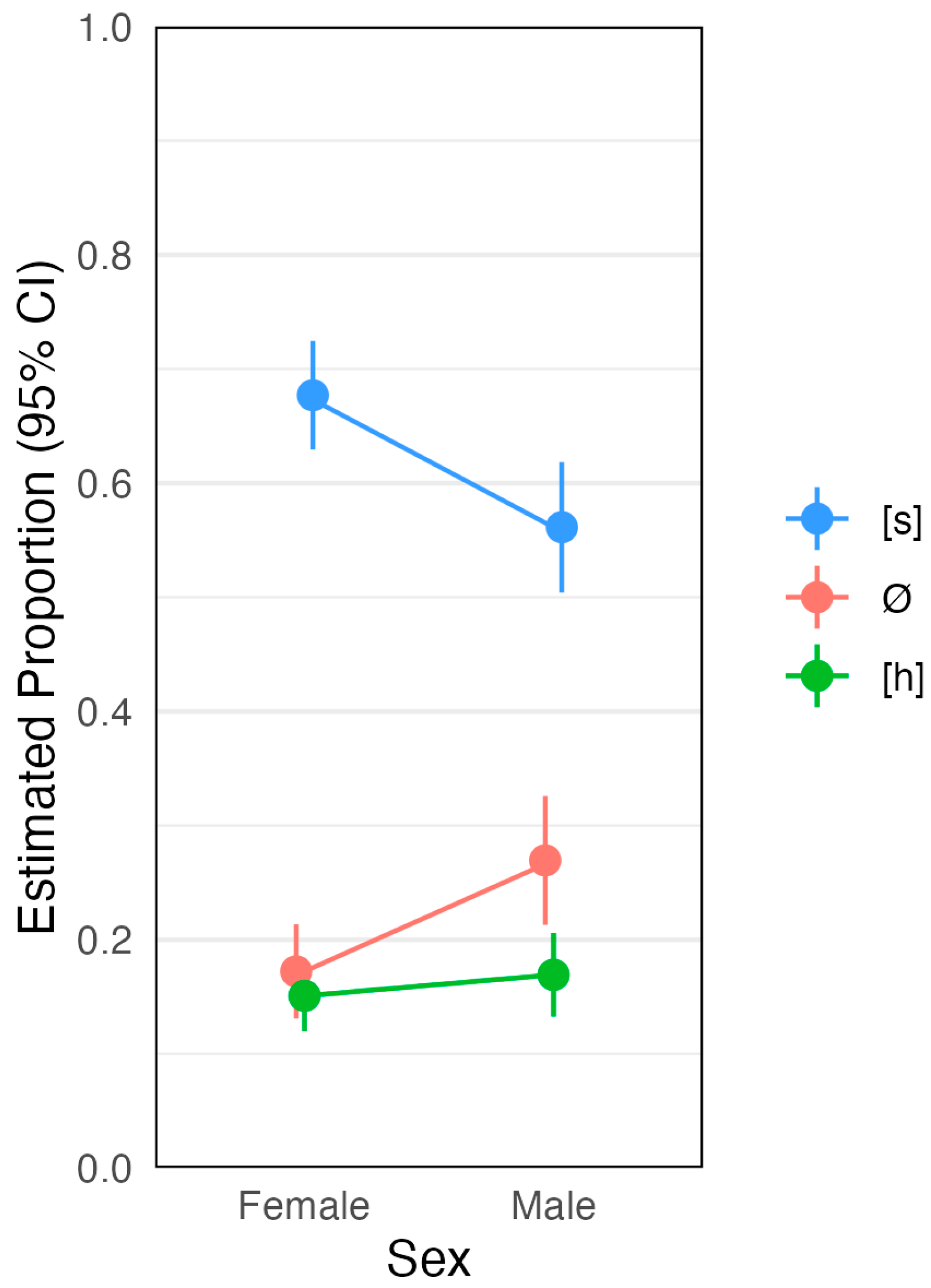

In regard to the behavior of the sibilant in Lima, the results support several interpretative hypotheses. Firstly, the influence of internal linguistic factors, such as the previous and following segment and syllable stress, which has remained constant in the evolution of sibilants in many Spanish-speaking areas, is confirmed. Secondly, social factors, such as biological sex, neighborhood, and educational level, along with different migratory generations, shape linguistic change in unique ways compared to other Spanish-speaking communities.

For example, different variants of /s/ have gained particular social significance in Lima, where in the second half of the twentieth and first part of the twentieth centuries there has been constant contact between classic Limeño speakers and those who speak Andean Spanish. In Lima, where Andean migrants have faced widespread discrimination, the contact between Andean and Limeño varieties has been conflictive. In previous analyses of the perception of linguistic variants in Lima (

Caravedo, 2014), it has been noted that Andean Spanish speakers have assigned an indexical meaning to the aspiration found in classic Limeño speech. Conversely, the preservation of [s] in syllabic coda identifies Andean speakers from the perspective of classic Limeños, thus also having an indexical value. In our study, first-generation Andean speakers in Lima produced the sibilant in word final position in significantly higher proportions than the second, third and fourth generations when the following segment was a voiced or an unvoiced consonant. Because Andean culture and speech have traditionally indexed rurality, poverty, and backwardness in Lima, a high proportion of word final [s] is perceived negatively by classic Limeños (

Caravedo, 2014). In addition, the Andean /s/ is perceived as different from the Limeño /s/ from an articulatory standpoint. The former is characterized in the literature (

Escobar, 1978) as apico-alveolar with a high degree of stridency and is reinforced in coda position, while the latter is dental and shorter than the Andean [s]. These differences are apparent in the spectrograms below of sibilants in final prepausal position of a first-generation Andean migrant (

Figure 13) and a classic Limeño speaker (

Figure 14). The spectrograms reveal the longer duration and intensity of word final [s] in Andean Spanish in contrast to the [s] produced by the classic Limeño, which has resulted in classic Limeños perceiving greater phonetic intensity as characteristic of the Andean variety.

Regarding the aspirated Limeño variant, Andean speakers consider it deviant, despite recognizing it as typical of Lima (

Caravedo, 2014). While the articulation of the sibilant is weaker in Lima, at the same time, Limeño aspiration does not constitute articulatory weakening, as the aspirated variant tends to be reinforced, approaching the velar fricative phoneme /x/, especially before velar consonants, such as [’axko] [’kuxko], which can be interpreted as assimilation to the place of articulation of the following consonant. Interestingly, this variant, common among upper-middle class Limeños, is not considered prestigious among Andeans (

Caravedo, 2014) and does not seem to serve as a model for imitation for most first-generation Andean migrants, although to confirm this hypothesis a perception test is needed.

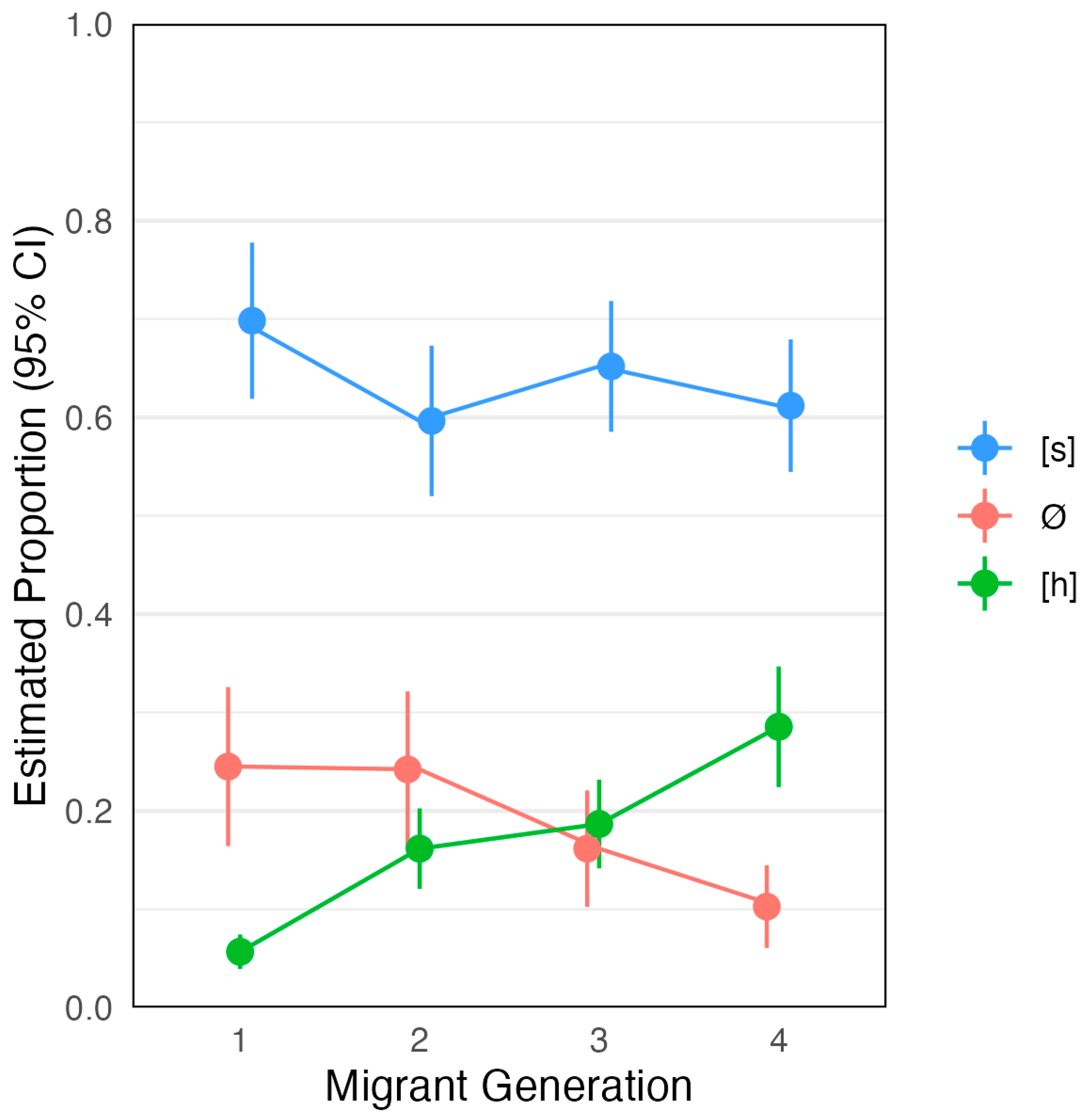

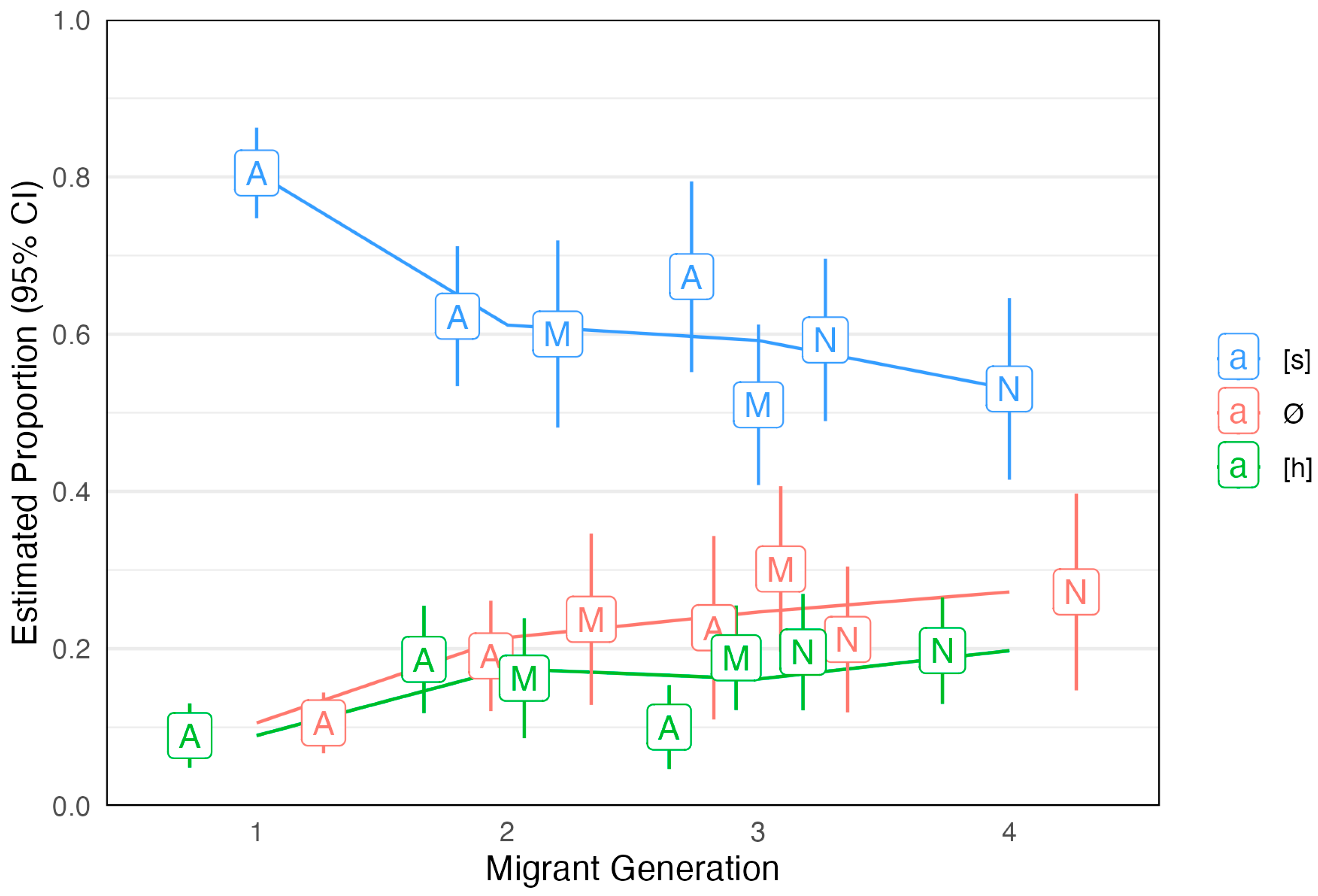

When first-generation Andean migrants weaken /s/, they overwhelmingly favor elision, with aspiration playing only a marginal role. The second generation continues to elide frequently but begins to show a modest increase in aspiration as well as a decrease in the sibilant. Third-generation speakers further advance this shift, increasing their use of aspiration and reducing elision, which signals an emerging alignment with urban Limeño patterns. Nonetheless, some second- and third-generation speakers with strong ethnolinguistic ties to the Andes continue to follow the norms of earlier generations, reflecting the persistence of Andean linguistic features within certain segments of the community. Overall, while both the second- and third-generations produce the sibilant at rates comparable to classic Limeños, they still aspirate less and elide more, particularly in specific phonetic contexts. These findings indicate a gradual but incomplete convergence toward Limeño norms across generations. Understanding this divergence more fully will require further research on how different sectors of Limeño society perceive and evaluate /s/ variants and how these social meanings influence the trajectory of linguistic change.

Regarding the first-generation speakers and the speakers from the two subsequent generations with more social ties to G1 speakers, the lower rates of [h] and [x], as well as the lack of prestige for [x] in Andean Spanish (

Caravedo, 2014) could be due, in part, to the structure of Quechuan phonology. With respect to the overall lower rates of [h], various Quechua varieties such as Cuzco Quechua, Bolivian Quechua, and Ayacucho Quechua, do have /h/ as a phoneme but, not as an allophone of /s/ and with very different phonotactic constraints from Spanish [h]. While in Spanish, [h] occurs as an allophone of /s/ in syllable-final and word-final positions, as well as word-initial position in some varieties, in Quechua, /h/ is almost strictly limited to syllable-initial position, especially in Ayacucho Quechua (

Parker, 1971, SAPhon Database). Thus, while /h/ and [h] exist in both Quechua and Andean Spanish, their phonotactic distributive differences in either language would potentially impede this process in Andean Spanish. Similar proposals for the lower levels of intervocalic spirantization of /d/ in Cuzco Spanish have been made by

Eager (

2018) and

Rogers et al. (

in press), namely, the lack of voiced obstruents in Quechua, has slowed the process of intervocalic lenition of /d/ in bilinguals, and subsequently been passed down as a feature of monolingual Spanish in the region through language shift. Similar phenomena have been documented in Yucatan Spanish due to contact with Yucatec Maya (

Michnowicz, 2009). A similar process may be occurring in the present dataset, in that speakers prefer [s] and elision to [h] in syllable-final position due to the passing down of this feature from Quechua-Spanish bilinguals to Spanish monolinguals, and subsequently to G2 and G3 speakers with more ties to G1 speakers. In other words, the shift of [h] from strictly syllable-initial contexts to syllable-final contexts may present a larger phonotactic and typological gap for bilinguals than other features, thus resulting in a lower frequency of [h] in syllable-final position in Andean Spanish.

Likewise, in the case of [x] preceding velar consonants, Quechua completely lacks phonemic velar fricatives. Taken in tandem with the phonotactical differences in /h/ and [h] in Quechua and Spanish, it is possible that [x] in syllable final position is even less common due to a potentially even larger phonotactic and typological gap between languages given that [x] is entirely absent from Quechuan segmental phonology. Notably, the appearance of G1 tendencies in some G2 and G3 speakers with more ties to G1, creates the interesting possibility that these tendencies could be identity markers to speakers, similar to [l] in Chicano English (

Van Hofwegen, 2009) and Miami Cuban English (

Rogers & Alvord, 2019), as well as vowels in Chilean Spanish (

Sadowsky, 2012). The possibilities of Quechua influence as well as lower levels of aspiration being an identity marker of the G1 linguistic community are intriguing and merit further study. Initial steps would be to compare /x/ in Andean Spanish to /x/ in Limeño Spanish to tease out any acoustic differences that could be attributed to contact with Quechua, as well as gathering perceptual data.

While these linguistic tendencies shed light on micro-level processes of contact and identity construction, understanding their distribution and social meaning requires situating them within the macro-level dynamics of Limeño society. The social factors influencing the Limeño sibilant extend beyond biological sex, socioeconomic strata, or differences in educational levels. They also include spatial mobility and the resulting social restructuring within the city. Therefore, objective quantitative results should be interpreted in light of the unique characteristics of a society like Peru’s. Future research using ethnographic methodology is needed to confirm our impressions of the social significance of these variants and to shed light on how they continue to evolve within this social restructuring.

6. Conclusions

Our analyses of /s/ variation in the demographic context of the city of Lima have shown the results of dialect contact between classic Limeño Spanish and Andean Spanish following a period of major demographic change. In spite of the presence in Lima of large numbers of speakers of Andean Spanish, a variety of Spanish in which the sibilant is maintained, /s/ weakening has seemingly expanded in the city since the 1980s when comparing our results with those of

Caravedo (

1990). First-generation Andean migrants maintain high levels of the sibilant in syllable-final position. In contrast, their descendants (i.e., second- and third-generation migrants in the city) display lower proportions of sibilant maintenance, to the point that they approach the values of classic Limeños, suggesting an accommodation to the perceived patterns of the city.

When /s/ weakening occurs in the speech of first-generation Andean migrants, elision is favored over aspiration, unlike the working-class classic Limeños in our study, who more frequently use aspiration. This preference for elision may reflect the influence of Quechua on the migrants’ speech patterns. We hypothesize that both aspiration and elision have taken on distinct social meanings in Lima and that aspiration is not considered prestigious among Andean Spanish speakers. However, the social perceptions of aspiration and elision seem to change by the third generation as speakers produce lower levels of elision and higher rates of aspiration, approaching but not aligning completely with the speech of classic Limeños. Elision is a phenomenon linked primarily to males and social groups with lower educational attainment in poorer neighborhoods of the city. It is noteworthy that in Los Olivos, a neighborhood of socially ascending migrants, the rate of elision decreases compared to traditional migrant neighborhoods.

In regard to linguistic factors, our results are similar to those in most previous studies. The sibilant was produced at higher frequencies in a stressed syllable and when followed by a vowel or a pause in contrast to a voiced or voiceless consonant. It also occurred more frequently when the preceding vowel was high rather than non-high. Elision occurred more frequently than aspiration in unstressed syllables and when followed by a pause, a vowel, or a voiced consonant.

The results presented here confirm the predominance of the sibilant in Lima over a period that spans from the late 20th to the early 21st century and show change across migrant generations. Further studies with more recent corpora comprising the third and fourth generations of migration, the new Limeños, are necessary to confirm or nuance the evolutionary trends of one of the most variable phonemes in Spanish in a historically conservative city.