Referent Reintroduction in the Japanese Narratives of Bilingual Children: The Relationship Between Referent Accessibility and Explicitness

Abstract

1. Introduction and Theoretical Background

1.1. Referential Choice and Information Structure in Narratives

1.2. The Development of Referential Choice in Child Narratives

1.3. Accessibility Features Modulating Referential Choice in Narrative Discourse

1.4. Bilingual Development and CLI

1.5. Referential Expressions in Japanese

1.6. Research Questions

- (1)

- Which accessibility features (recency, ambiguity, predictability) contribute to bilingual and monolingual differences in reference choice (NP, pronoun, null), and how are they different?

- (2)

- If bilinguals use more NPs than monolinguals, are these always “redundant”? That is, are these restricted to accessible contexts?

2. Methods

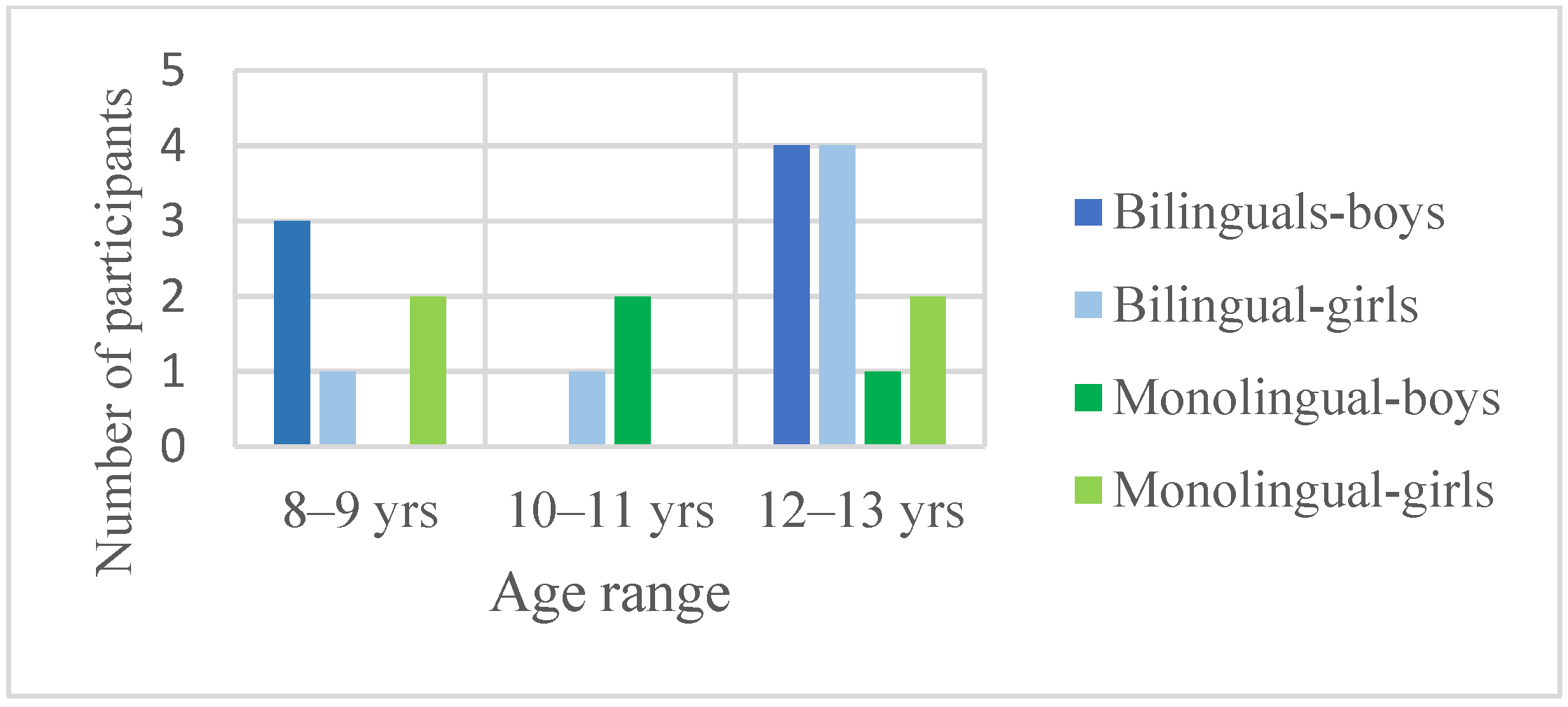

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Transcription and Coding

| Example 1: B-12 (bilingual, 9 years old) | ||||

| 1. あるところに男の子がいました。 | ||||

| arutokoroni | otokonoko | ga | imashita. | |

| once upon a time | boy | NOM | be-PAST | |

| ‘Once upon a time there was a boy.’ | ||||

| 2. ある夜、その男の子のペットのカエルがゲージから逃げ出しました。 | |||||||

| aru yoru | sono otokonoko | no | petto | no | kaeru ga | geeji kara | |

| one night | that boy | GEN | Pet | GEN | frog NOM | gage LOC | |

| nigedashiteshimaimashita. | |||||||

| escape-regrettably-PAST | |||||||

| ‘One evening, the Frog, the boy’s pet, escaped from the cage.’ | |||||||

| 3. 男の子は起きて、 | |||

| otokonoko wa | okite. | [after 1 intervening clause] | |

| Boy TOP | wake-up-TE | ||

| ‘The boy wakes up, and,’ | |||

| Example 2: B-6 (bilingual, 9 years old) | ||||||||

| 1. 一人の男の子が犬、じゃなくてカエルを拾いました。 | ||||||||

| hitorino | otokonoko | ga | inu | janakute | kaeru | o | hiroimashita. | |

| one | boy | NOM | dog | COP-NEG-TE | frog | ACC | pick-PAST | |

| ‘A boy found a dog, no, a Frog.’ | ||||||||

| 2. 犬が瓶の中を見てます。 | |||||

| inu ga | bin no | nakaaka | o | mitemasu. | |

| dog NOM | jar GEN | inside | ACC | looking-NONPAST | |

| ‘The dog is looking into the jar.’ | |||||

| 3. やがて夜になったので | ||||

| yagate | yoru | ni natta | node | |

| eventually | night | become-PAST | therefore | |

| ‘As night came on,’ | ||||

| 4. 男の子は寝てしまいました。 | ||||

| otokonoko | wa | neteshimaimashita. | [multiple possible characters] | |

| boy | TOP | sleep-completed-PAST | ||

| ‘The boy fell asleep.’ | ||||

| Example 3: B-7(bilingual, 13 years old) | |||||||||||||

| 1. 夜に、えっと、犬と男の子がカエルを、ん、瓶の中に入れて[//]入れました。 | |||||||||||||

| yoru | ni | e:tto | inu | to | otokonoko | ga | kaeru | o | n: | bin | no | naka ni | |

| night | at | Um… | dog | and | boy | NOM | frog | ACC | Um… | jar | GEN | inside LOC | |

| irete [//] iremashita. | |||||||||||||

| put-inside-PAST | |||||||||||||

| ‘At night, uh, a dog and a boy put a Frog in a jar.’ | |||||||||||||

| 2. でもその瓶は蓋がしまってなくて、 | |||||||

| demo | sono | bin | wa | futa | ga | shimattenakute | |

| but | that | jar | TOP | lid | NOM | not-closed-and | |

| ‘But since the jar did not have a lid,’ | |||||||

| 3. カエルが出てしまいました。 | ||||

| kaeru | ga | deteshimaimashita. | [predictable from previous discourse] | |

| frog | NOM | go-out-completed-PAST | ||

| ‘the Frog got out of it.’ | ||||

| Example 4: B-8 (bilingual, 13 years old) | ||||||||||

| 1. たぶん男の子がカエルを瓶の中に閉じ込めて | ||||||||||

| tabun | otokonoko | ga | kaeru | o | bin | no | naka | ni | tojikomete | |

| Perhaps | boy | NOM | frog | ACC | jar | GEN | inside | LOC | confine-TE | |

| [predictable from verb semantics] | ||||||||||

| ‘Perhaps the boy trapped the Frog in the jar.’ | ||||||||||

2.4. Analysis

| Accessibility | High Accessibility | Low Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Referential Form | Null (>NP) | NP (>Null) |

| 1. Recency: number of intervening clauses (IC) | 1 to 2 IC | 3 or more IC |

| 2. Ambiguity: # of characters in the scene | Single character | Multiple characters |

| 3. Predictability: Semantic implication | Predictable from verb semantics/previous discourse | Unpredictable |

3. Results

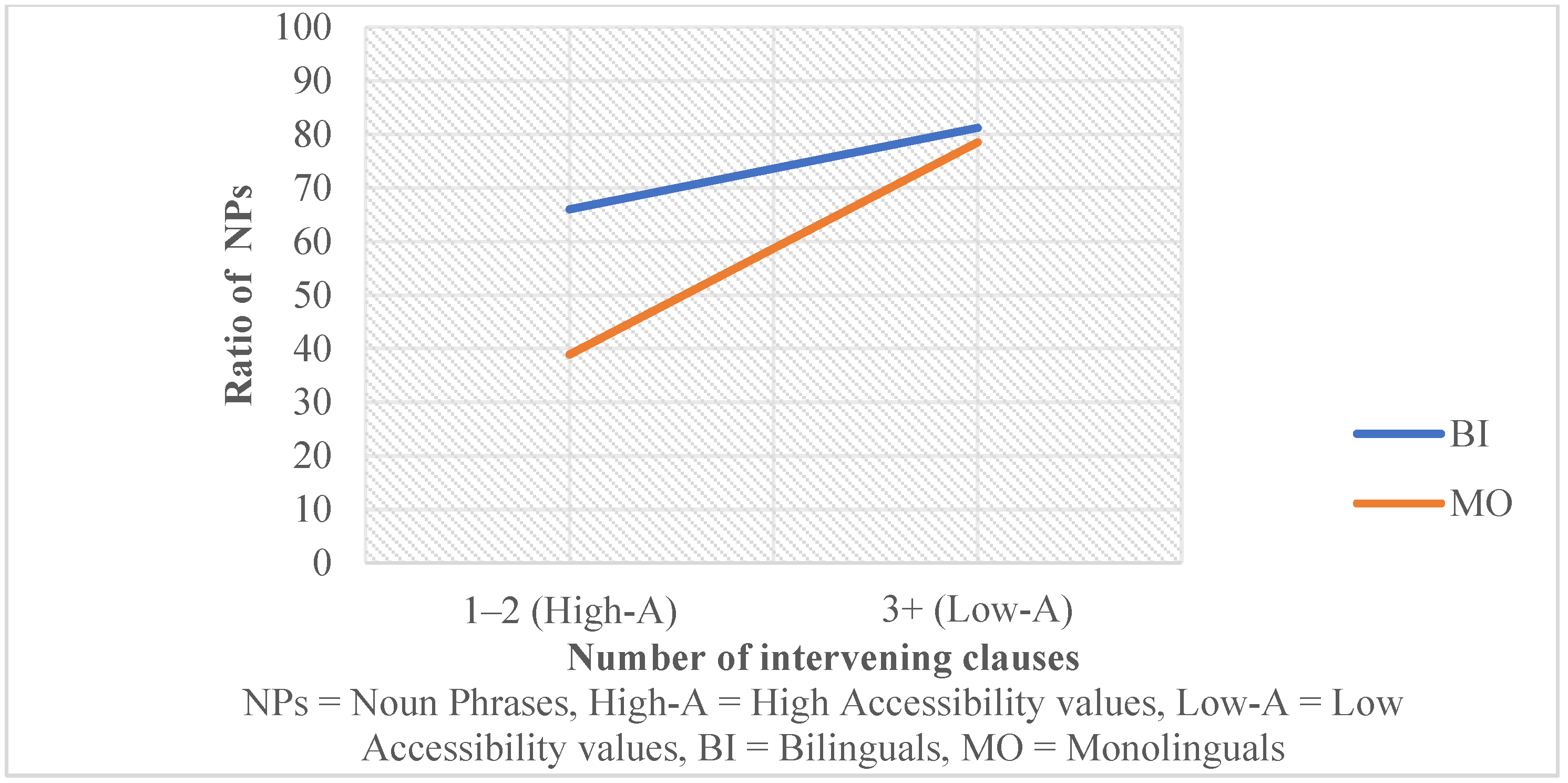

3.1. Recency

3.1.1. Recency: Frog Story

| Bilingual (n = 13) | Monolingual (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| 1–2 IC | 66.0% | 34.0% | 100% | 38.9% | 61.6% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (123) | (60) | (1) | (184) | (33) | (46) | (0) | (79) |

| 3+ IC | 81.2% | 18.8% | 100% | 78.5% | 21.5% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (89) | (14) | (4) | (107) | (37) | (8) | (0) | (45) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.403 | 0.090 | −4.467 | 7.942 × 10−6 ** |

| GroupB | −0.483 | 0.196 | −2.463 | 1.379 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.219 | 0.139 | 1.571 | 1.163 × 10−1 |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.471 | 0.277 | 1.702 | 8.885 × 10−2 + |

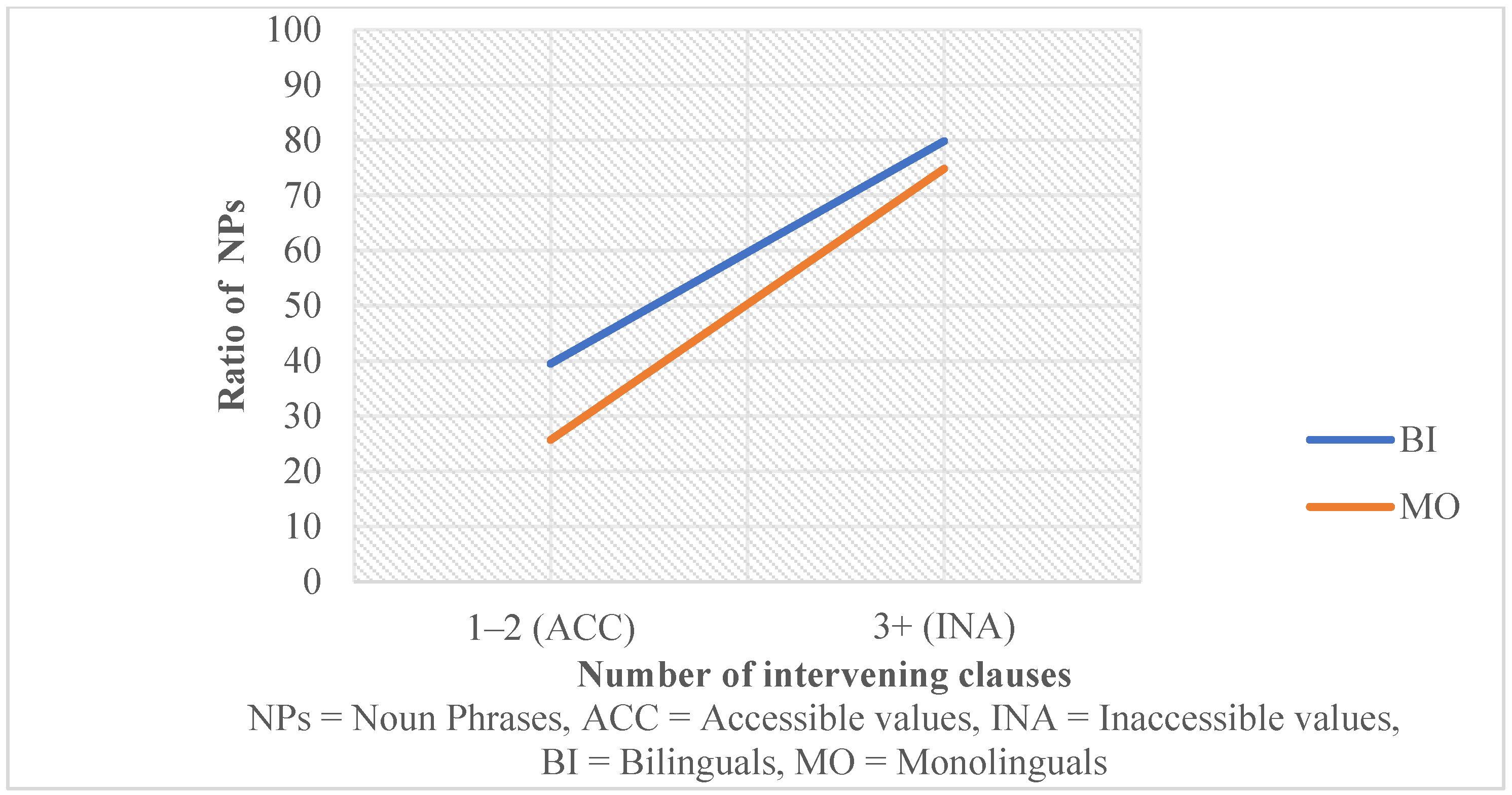

3.1.2. Recency: Chaplin Story

| Bilingual (n = 11) | Monolingual (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | |

| 1–2 IC | 39.5% | 60.5% | 100% | 25.7% | 74.3% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (72) | (98) | (1) | (171) | (18) | (61) | (1) | (80) |

| 3+ IC | 79.8% | 20.2% | 100% | 74.8% | 25.2% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (63) | (16) | (0) | (79) | (30) | (12) | (1) | (43) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.859 | 0.118 | −7.290 | 3.099 × 10−13 *** |

| GroupB | −0.607 | 0.264 | −2.304 | 2.120 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.571 | 0.186 | 3.067 | 2.164 × 10−3 ** |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.681 | 0.371 | 1.835 | 6.654 × 10−2 + |

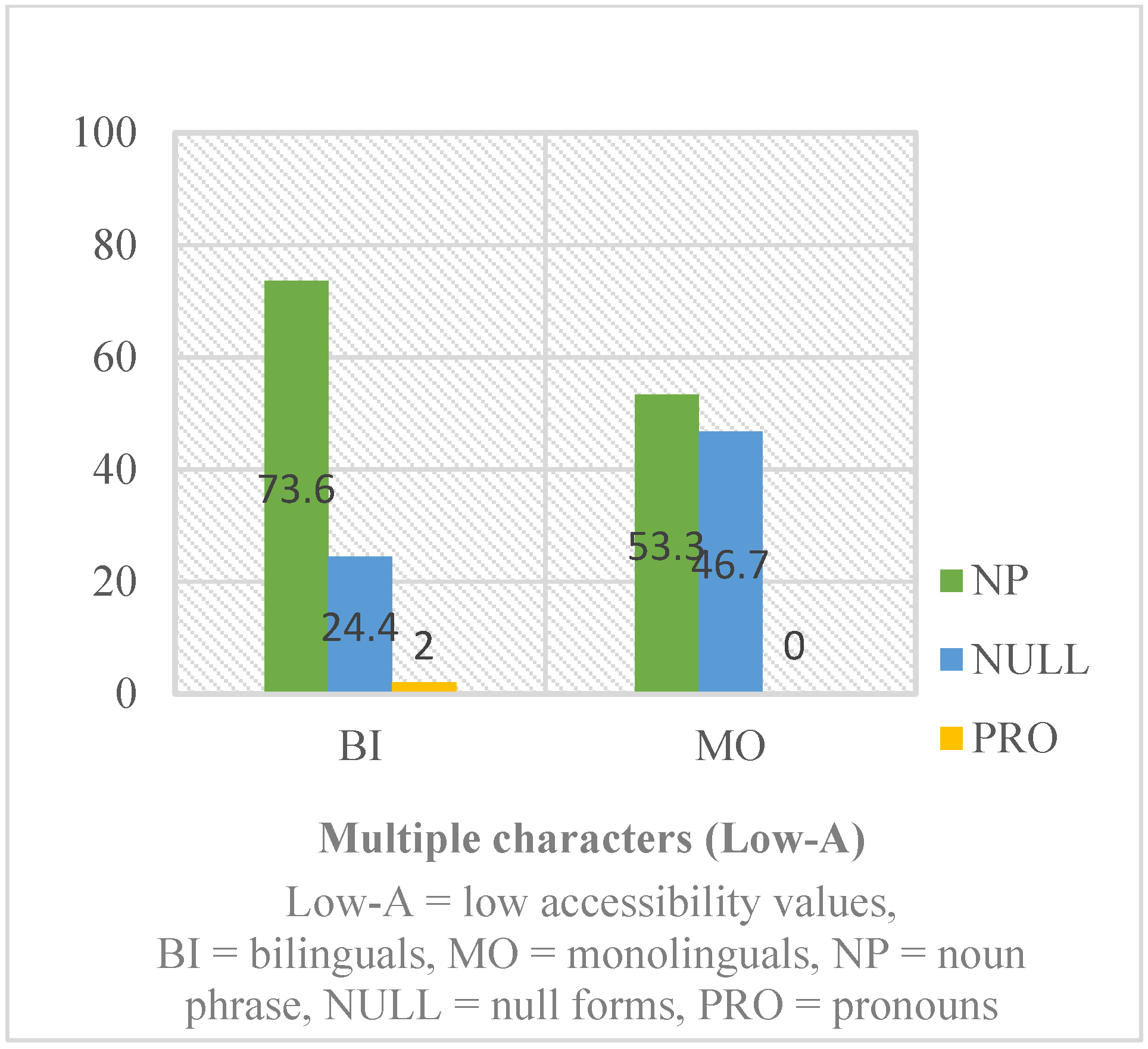

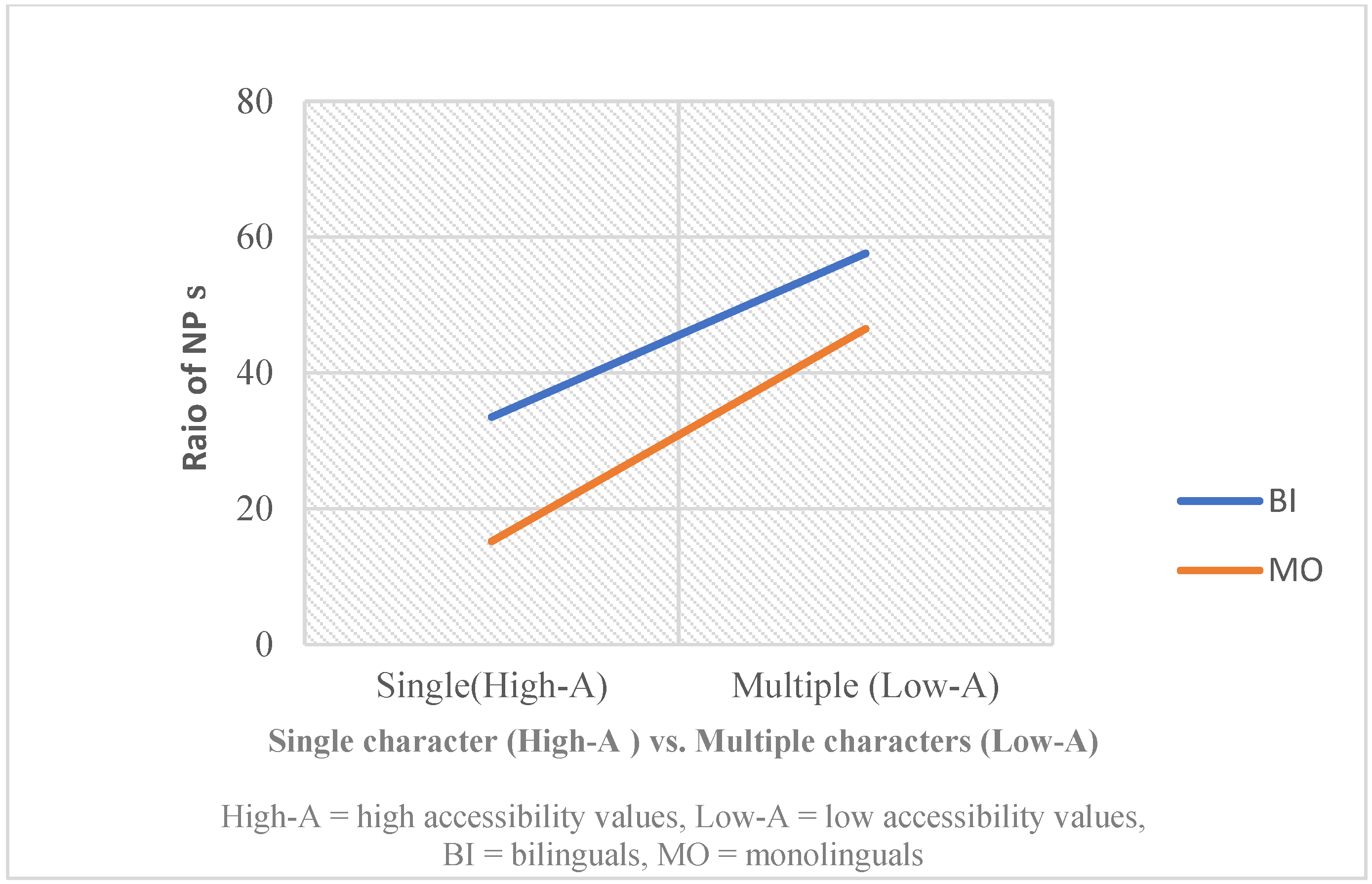

3.2. Ambiguity

3.2.1. Ambiguity: Frog Story

| Bilinguals (BI) (n = 13) | Monolinguals (MO) (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Single (High-A) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple | 72.4% | 27.6% | 100% | 53.3% | 46.7% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (217) | (72) | (6) | (295) | (69) | (54) | (0) | (123) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.307 | 0.070 | −4.405 | 1.058 × 10−5 |

| GroupB | −0.325 | 0.141 | −2.309 | 2.097 × 10−2 |

3.2.2. Ambiguity: Chaplin Story

| Bilinguals (n = 11) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | |

| Single | 33.5% | 66.5% | 100% | 15.2% | 84.8% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (16) | (26) | (1) | (43) | (5) | (27) | (1) | (33) |

| Multiple | 57.6% | 42.4% | 100% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (144) | (92) | (1) | (237) | (46) | (53) | (0) | (99) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.802 | 0.277 | −2.893 | 3.817 × 10−3 ** |

| GroupB | −0.296 | 0.385 | −0.769 | 4.418 × 10−1 |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.243 | 0.292 | 0.830 | 4.066 × 10−1 |

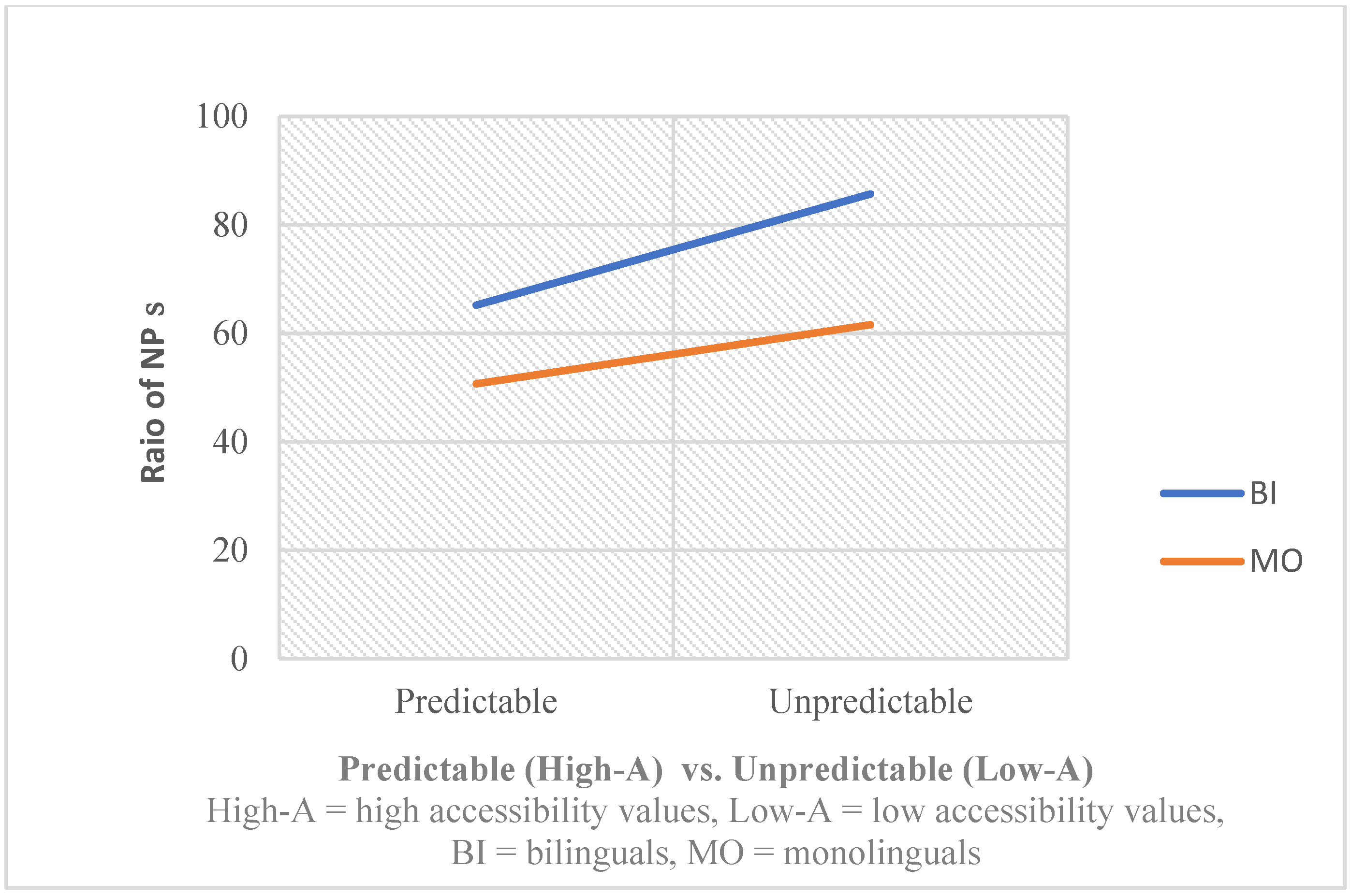

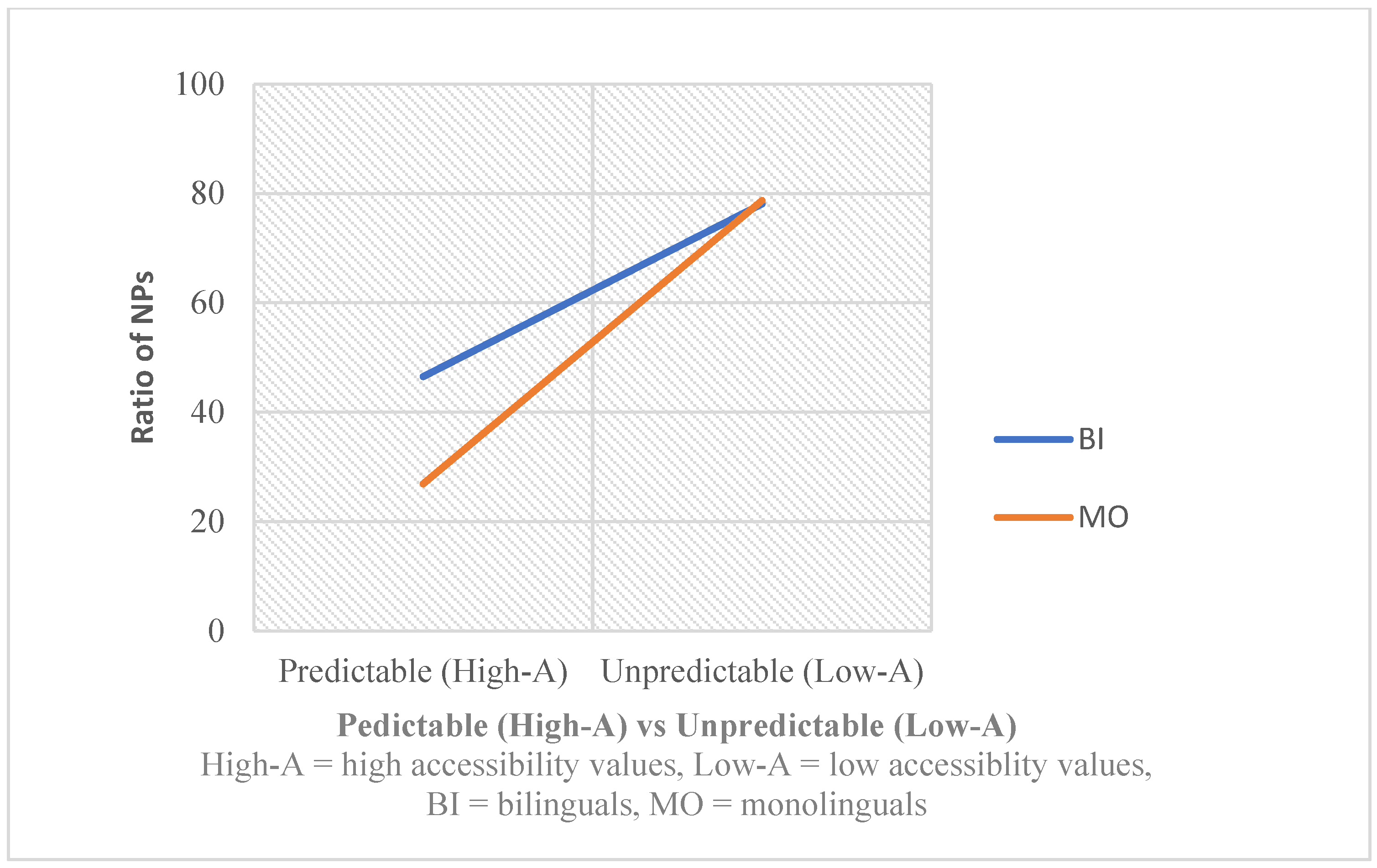

3.3. Predictability

3.3.1. Predictability: Frog Story

| Bilinguals (n = 13) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Predictable | 65.2% | 34.8% | 100% | 50.7% | 49.3% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (131) | (64) | (3) | (198) | (49) | (43) | (0) | (92) |

| Unpredictable | 85.7% | 14.3% | 100% | 61.6% | 38.4% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (91) | (11) | (3) | (105) | (20) | (13) | (0) | (33) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.366 | 0.091 | −4.048 | 5.172 × 10−5 *** |

| GroupB | −0.377 | 0.184 | −2.048 | 4.058 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.197 | 0.146 | 1.351 | 1.768 × 10−1 |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.045 | 0.311 | 0.144 | 8.851 × 10−1 |

3.3.2. Predictability: Chaplin Story

| Bilinguals (n = 11) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Predictable | 46.5% | 53.5% | 100% | 26.9% | 73.1% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (108) | (109) | (1) | (218) | (24) | (74) | (0) | (98) |

| Unpredictable | 78.1% | 21.9% | 100% | 78.7% | 21.3% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (55) | (13) | (2) | (70) | (28) | (8) | (1) | (37) |

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.702 | 0.096 | −7.299 | 2.895 × 10−13 *** |

| GroupB | −0.807 | 0.238 | −3.384 | 7.144 × 10−4 *** |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.415 | 0.226 | 1.838 | 6.612 × 10−2 *+ |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.807 | 0.426 | 1.892 | 5.845 × 10−2 + |

3.4. Individual Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Accessibility Features and Bilingual–Monolingual Differences in Referential Choice

4.2. How Can Bilinguals’ Overproduction Be Accounted for?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Two more monolingual children participated, but the data was excluded since they told a first-person narrative, referring to the main character as boku ‘I”. |

| 2 | SI refers to the number of clauses per the number of T-units (Miller et al., 2019). |

References

- Adam, C. (Director). (2012). Chaplin and co (The Museum Guard) [Video]. Anderson Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, M. (2020). The effects of updating and proficiency on overspecification in American Greek children. European Journal of Psychological Research, 7(1), 26–32. Available online: https://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Full-Paper-THE-EFFECTS-OF-UPDATING-AND-PROFICIENCY-ON-OVERSPECIFICATION-IN-AMERICAN-GREEK-CHILDREN.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Andreou, M., Torregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. (2023). The use of null subjects by Greek-Italian bilingual children: Identifying cross-linguistic effects. In G. Fotiadou, & I. M. Tsimpli (Eds.), Individual differences in anaphora resolution: Language and cognitive effects (pp. 166–191). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, M., Torregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. M. (2020). The sharing of reference strategies across two languages: The production and comprehension of referring expressions by Greek-Italian bilingual children. Discours. Revue de Linguistique, Psycholinguistique et Informatique. A Journal of Linguistics, Psycholinguistics and Computational Linguistics, [online], 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyri, E., & Sorace, A. (2007). Cross-linguistic influence and language dominance in older bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(1), 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, M. (1990). Accessing noun-phrase antecedents (RLE Linguistics B: Grammar). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J. E. (2010). How speakers refer: The role of accessibility. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(4), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. E., Bennetto, L., & Diehl, J. J. (2009). Reference production in young speakers with and without autism: Effects of discourse status and processing constraints. Cognition, 110(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, J. E., & Griffin, Z. M. (2007). The effect of additional characters on choice of referring expression: Everyone counts. Journal of Memory and Language, 56(4), 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M. G. (1987). The acquisition of narratives: Learning to use language. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, D., Gertken, L. M., & Amengual, M. (2012). Bilingual language profile: An easy-to-use instrument to assess bilingualism. COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://blp.coerll.utexas.edu (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Bock, J. K., & Warren, R. K. (1985). Conceptual accessibility and syntactic structure in sentence formulation. Cognition, 21(1), 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L., & Cheek, E. (2017). Gender identity in a second language: The use of first person pronouns by male learners of Japanese. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(2), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, W. (1976). Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics and point of view. In C. N. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 25–56). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, W. (1994). Discourse, consciousness, and time: The flow and displacement of conscious experience in speaking and writing. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., & Lei, J. (2012). The production of referring expressions in oral narratives of Chinese–English bilingual speakers and monolingual peers. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 29(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, P. M. (1992). Referential strategies in the narratives of Japanese children. Discourse Processes, 15(4), 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, P. M. (1997). Discourse motivations for referential choice in Korean acquisition. In H. M. Sohn, & J. Haig (Eds.), Japanese/Korean linguistics 6 (pp. 639–659). CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Colozzo, P., & Whitely, C. (2014). Keeping track of characters: Factors affecting referential adequacy in children’s narratives. First Language, 34(2), 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daller, M. H., Treffers-Daller, J., & Furman, R. (2011). Transfer of conceptualization patterns in bilinguals: The construal of motion events in Turkish and German. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 14(1), 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, B., & Housen, T. (2017). A cross-linguistic perspective on syntactic complexity in L2 development: Syntactic elaboration and diversity. The Modern Language Journal, 101, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, J. W. (1987). The discourse basis of ergativity. Language, 63(4), 805–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (Ed.), Linguistics in the morning calm (pp. 111–138). Hanshin Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina, N., & Bohnacker, U. (2022). A new perspective on referentiality in elicited narratives: Introduction to the special issue. First Language, 42(2), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. (1983). Topic continuity in discourse: An introduction. In Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study (pp. 1–41). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gundel, J. K., Hedberg, N., & Zacharski, R. (1993). Cognitive status and the form of referring expressions in discourse. Language, 69(2), 274–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haznedar, B. (2010). Transfer at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Pronominal subjects in bilingual Turkish. Second Language Research, 26(3), 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, M. (2003). Children’s discourse: Person, space, and time across languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hickmann, M., & Hendriks, H. (1999). Cohesion and anaphora in children’s narratives: A comparison of English, French, German, and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language, 26(2), 419–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickmann, M., Hendriks, H., Roland, F., & Liang, J. (1996). The marking of new information in children’s narratives: A comparison of English, French, German and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language, 23(3), 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, M., Schimke, S., & Colonna, S. (2015). From early to late mastery of reference: Multifunctionality and linguistic diversity. In L. Serratrice, & S. E. M. Allen (Eds.), The acquisition of reference (pp. 181–211). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, J. (1983). Topic continuity in Japanese. In T. Givón (Ed.), Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study (pp. 43–93). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E., & Allen, S. E. (2013). The effect of individual discourse-pragmatic features on referential choice in child English. Journal of Pragmatics, 56, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, N. (2006). Syntactic complexity measures and their relation to oral proficiency in Japanese as a foreign language. Language Assessment Quarterly: An International Journal, 3, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1985). Language and cognitive processes from a developmental perspective. Language and Cognitive Processes, 1(1), 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, S. (1975). Three perspectives in the functional approach to syntax. In R. E. Grossman, L. J. San, & T. J. Vance (Eds.), Papers on the parasession on functionalism. Chicago Linguistic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Küntay, A. C. (2002). Development of the expression of indefiniteness: Presenting new referents in Turkish picture-series stories. Discourse Processes, 33(1), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A., Donley, K., & Bermúdez, B. (2021). The English referencing behaviors of first-and second-grade Spanish–English emergent bilinguals in oral narrative retells. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(5), 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, J. R. (2013). Pragmatic perspectives on the second language acquisition of person reference in Japanese: A longitudinall study [Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University]. Available online: http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/1875 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Maratsos, M. P. (1974). Preschool children’s use of definite and indefinite articles. Child Development, 45(2), 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y. (2024). (Non) referentiality of silent reference in Japanese conversation: How and what are inferred. In (Non) referentiality in conversation (pp. 103–122). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, where are you? Dial Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. F., Andriacchi, K. D., & Nockerts, A. (2019). Assessing language production using SALT software: A clinician’s guide to language sample analysis. SALT Software, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Minagawa, H. (2016). Submergence of lexically encoded egocentricity in syntax: The case of subjective emotion predicates in Japanese. Journal of Japanese Linguistics, 32(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, M. (2011). Telling stories in two languages: Multiple approaches to understanding English–Japanese bilingual children’s narratives. Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mishina-Mori, S. (2020). Cross-linguistic influence in the use of objects in Japanese/English simultaneous bilingual acquisition. International Journal of Bilingualism, 24(2), 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina-Mori, S., Nakano, Y., Yujobo, Y. J., & Kawanishi, Y. (2024). Is referent reintroduction more vulnerable to crosslinguistic influence? An analysis of referential choice among Japanese–English bilingual children. Languages, 9(4), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2010). Dominant language transfer in adult second language learners and heritage speakers. Second Language Research, 26(3), 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2016). Dominance and proficiency in early and late bilingualism. In C. Silva-Corvalan, & J. Treffers-Daller (Eds.), Language dominance in bilinguals: Issues of measurement and operationalization (pp. 15–35). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muranaka-Vuletich, H. (2024). Violations of the basic Japanese referential system in reintroductions. Journal of Japanese Linguistics, 40(1), 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K. (1993). Referential structure in Japanese children’s narratives: The acquisition of wa and ga. In S. Choi (Ed.), Japanese/Korean linguistics (Vol. 3, pp. 84–99). CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y. (2019). Immediate input quality is not a determining factor: Crosslinguistic influence on subject realization in a simultaneous Japanese–English bilingual child. Studies in Language Sciences: The Journal for the Japanese Society for Language Sciences, 18, 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T., & Thompson, S. A. (1997, February 14–17). Deconstructing “zero anaphora” in Japanese. Twenty-Third Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General Session and Parasession on Pragmatics and Grammatical Structure (pp. 481–491), Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Orfitelli, R., & Hyams, N. (2012). Children’s grammar of null subjects: Evidence from comprehension. Linguistic Inquiry, 43(4), 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolini, M., Rossi, F., & Pontecorvo, C. (1996). Re-introduction of referents in Italian children’s narratives. Journal of Child Language, 23, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshima-Takane, Y., MacWhinney, B., Sirai, H., Miyata, S., & Naka, N. (1998). CHILDES for Japanese (2nd ed., The JCHAT project). Chukyo University. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowska, A., Opacki, M., Mieszkowska, K., Białecka-Pikul, M., Wodniecka, Z., & Haman, E. (2022). Polish–English bilingual children overuse referential markers: MLU inflation in Polish-language narratives. First Language, 42(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., & Genesee, F. (1996). Syntactic acquisition in bilingual children: Autonomous or interdependent? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., & Navarro, S. (2003). Subject realization and crosslinguistic interference in the bilingual acquisition of Spanish and English: What is the role of the input? Journal of Child Language, 30, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, E. F. (1981). Toward a taxonomy of given-new information. In P. Cole (Ed.), Radical pragmatics (pp. 223–256). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, T., & Lozano, C. (2020). Which factors determine the choice of referential expressions in L2 English discourse?: New evidence from the COREFL corpus. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(5), 959–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. (2015). Overexplicit referent tracking in L2 English: Strategy, avoidance, or myth? Language Learning, 65(4), 824–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, L. (2005). The role of discourse pragmatics in the acquisition of subjects in Italian. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26(3), 437–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, L. (2007). Referential cohesion in the narratives of bilingual English-Italian children and monolingual peers. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(6), 1058–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, L., Sorace, A., & Paoli, S. (2004). Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Subjects and objects in English-Italian bilingual and monolingual acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 7(3), 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibatani, M. (1990). The languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sopata, A. (2021). Cross-linguistic influence in the development of null arguments in early successive bilingual acquisition. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 11(2), 192–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopata, A., Długosz, K., Brehmer, B., & Gielge, R. (2021). Cross-linguistic influence in simultaneous and early sequential acquisition: Null subjects and null objects in Polish-German bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(3), 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2011). Pinning down the concept of “interface” in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2016). Referring expressions and executive functions in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 6(5), 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A., & Filiaci, F. (2006). Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research, 22, 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A., Serratrice, L., Filiaci, F., & Baldo, M. (2009). Discourse conditions on subject pronoun realization: Testing the linguistic intuitions of older bilingual children. Lingua, 119(3), 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, A. (2018). Sougokooi niokeru shijihyougen (Referring expressions in interaction). Hitsuji Shoboo. [Google Scholar]

- Tenny, C. L. (2006). Evidentiality, experiencers, and the syntax of sentience in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 15(3), 245–288. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20100910 (accessed on 16 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. (2018). Teasing apart the effects of dominance, transfer, and processing in reference production by German-Italian bilingual adolescents. Languages, 3(3), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, J., Bongartz, C., & Tsimpli, I. M. (2019). Bilingual reference production: A cognitive-computational account. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 9(4–5), 569–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, J., & Korybski, T. (2016). Using lexical diversity measures to operationalize language dominance in bilinguals. In J. Treffers-Daller, & C. Silva-Corvalan (Eds.), Language dominance in bilinguals: Issues of measurement and operationalization (pp. 106–123). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, S. (2015). The (non)use of a third-person pronoun kanojo ‘she’ in L1 and L2 Japanese narratives. Buckeye East Asian Linguistics, 1, 23–27. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1811/73660 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Uehara, S., & Thepkanjana, K. (2014, December 12–14). The so-called person restriction of internal state predicates in Japanese in contrast with Thai. 28th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (pp. 120–128), Phuket, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, M., & Kehler, A. (2016). Grammatical and pragmatic factors in the interpretation of Japanese null and overt pronouns. Linguistics, 54(6), 1165–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherford, K. C., & Arnold, J. E. (2021). Semantic predictability of implicit causality can affect referential form choice. Cognition, 214, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A. M. Y., & Johnston, J. R. (2004). The development of discourse referencing in Cantonese-speaking children. Journal of Child Language, 31(3), 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, V., & Matthews, S. (2007). The bilingual child: Early development and language contact. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, Y., & MacWhinney, B. (2010). Honorifics: A sociocultural verb agreement cue in Japanese sentence processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31(3), 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishina-Mori, S.; Yujobo, Y.J.; Nakano, Y. Referent Reintroduction in the Japanese Narratives of Bilingual Children: The Relationship Between Referent Accessibility and Explicitness. Languages 2025, 10, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120294

Mishina-Mori S, Yujobo YJ, Nakano Y. Referent Reintroduction in the Japanese Narratives of Bilingual Children: The Relationship Between Referent Accessibility and Explicitness. Languages. 2025; 10(12):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120294

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishina-Mori, Satomi, Yuri Jody Yujobo, and Yuki Nakano. 2025. "Referent Reintroduction in the Japanese Narratives of Bilingual Children: The Relationship Between Referent Accessibility and Explicitness" Languages 10, no. 12: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120294

APA StyleMishina-Mori, S., Yujobo, Y. J., & Nakano, Y. (2025). Referent Reintroduction in the Japanese Narratives of Bilingual Children: The Relationship Between Referent Accessibility and Explicitness. Languages, 10(12), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120294