Hotspots of Inequity in Climate Adaptation: Explaining the Stratification of U.S. Ecowelfare Using Space-Time and Machine Learning Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Risk, Climate Justice, and Ecowelfare

1.2. Space-Time and Machine Learning Approaches to Ecosocial Inequality

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Measures

2.2. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

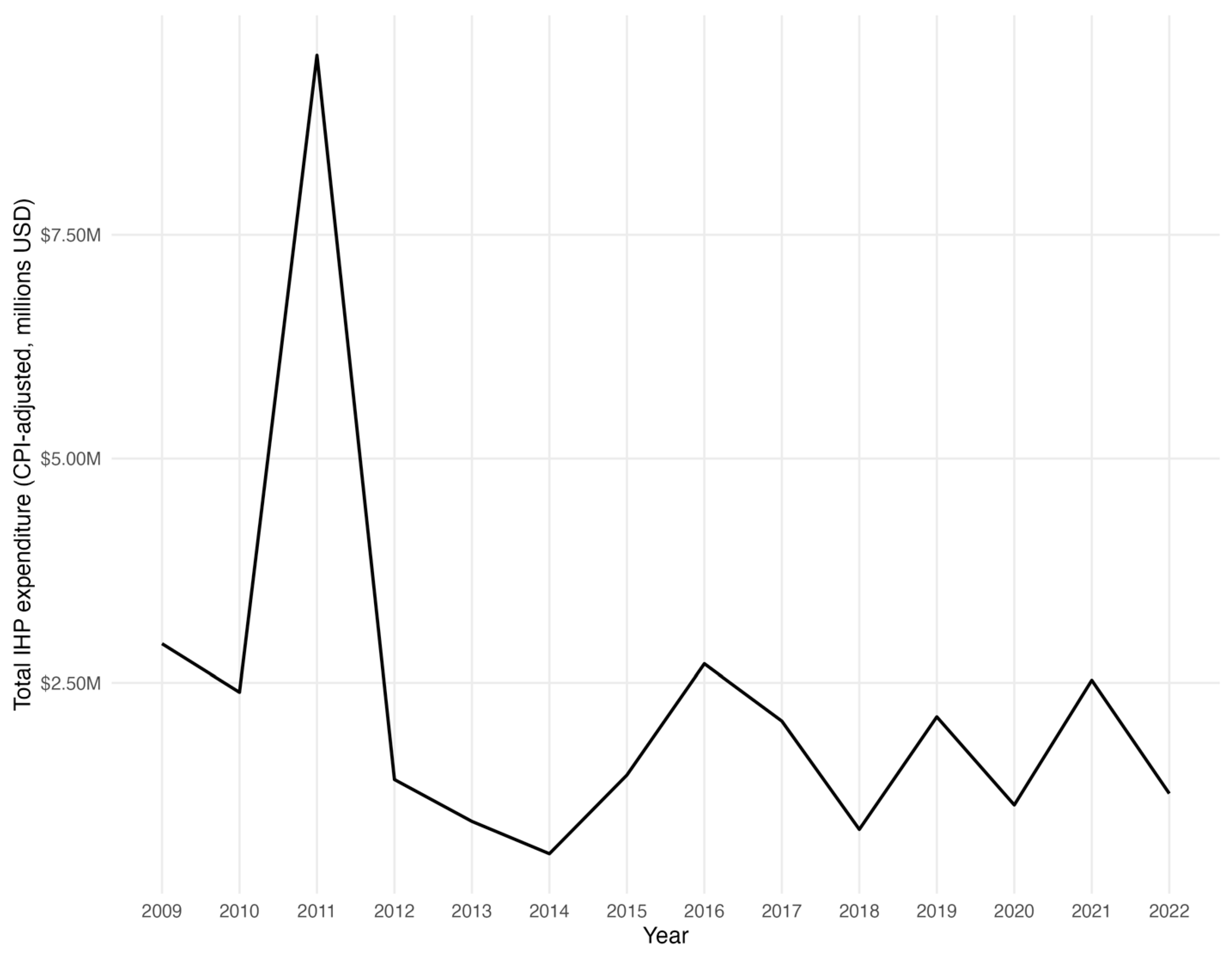

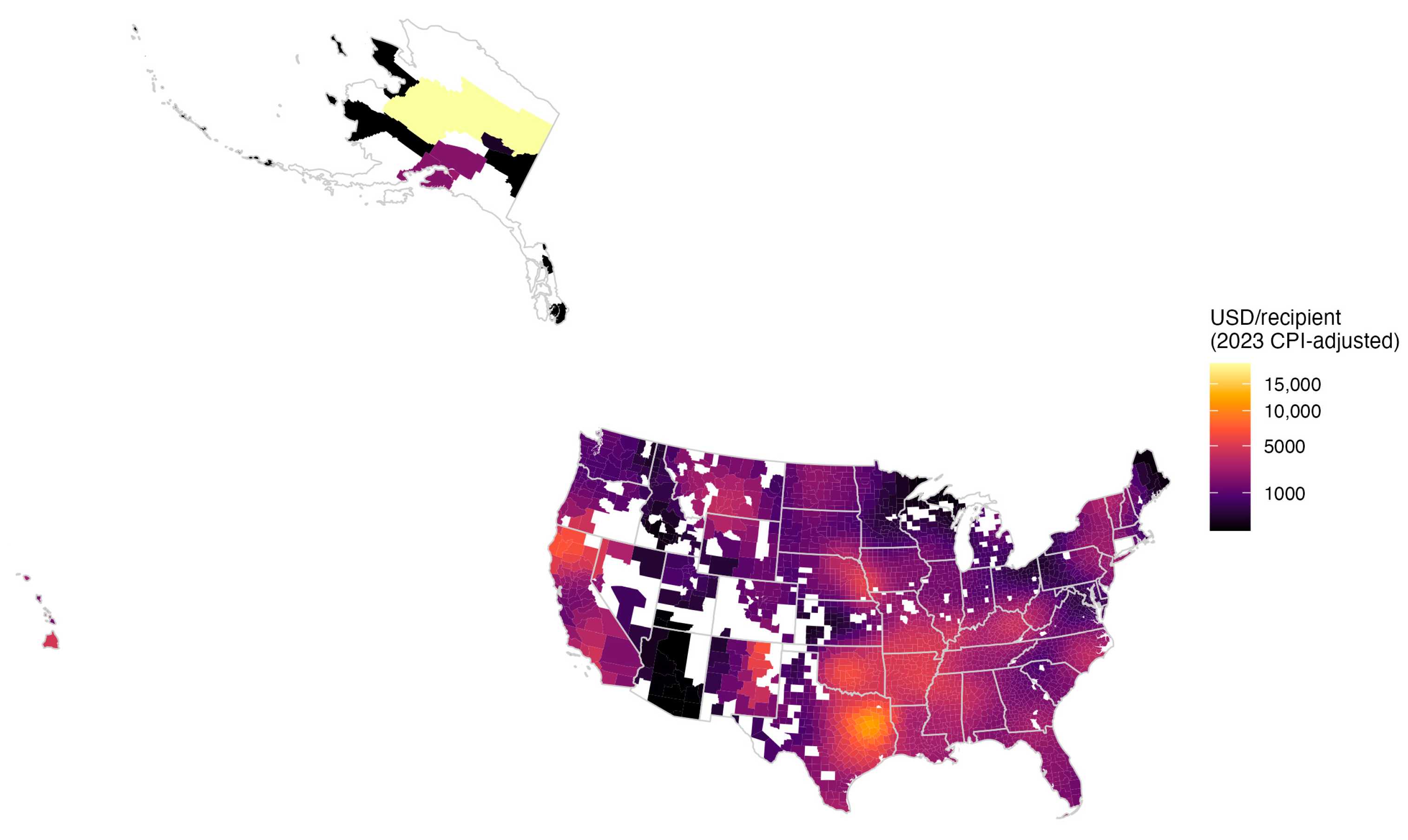

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Inferential Results

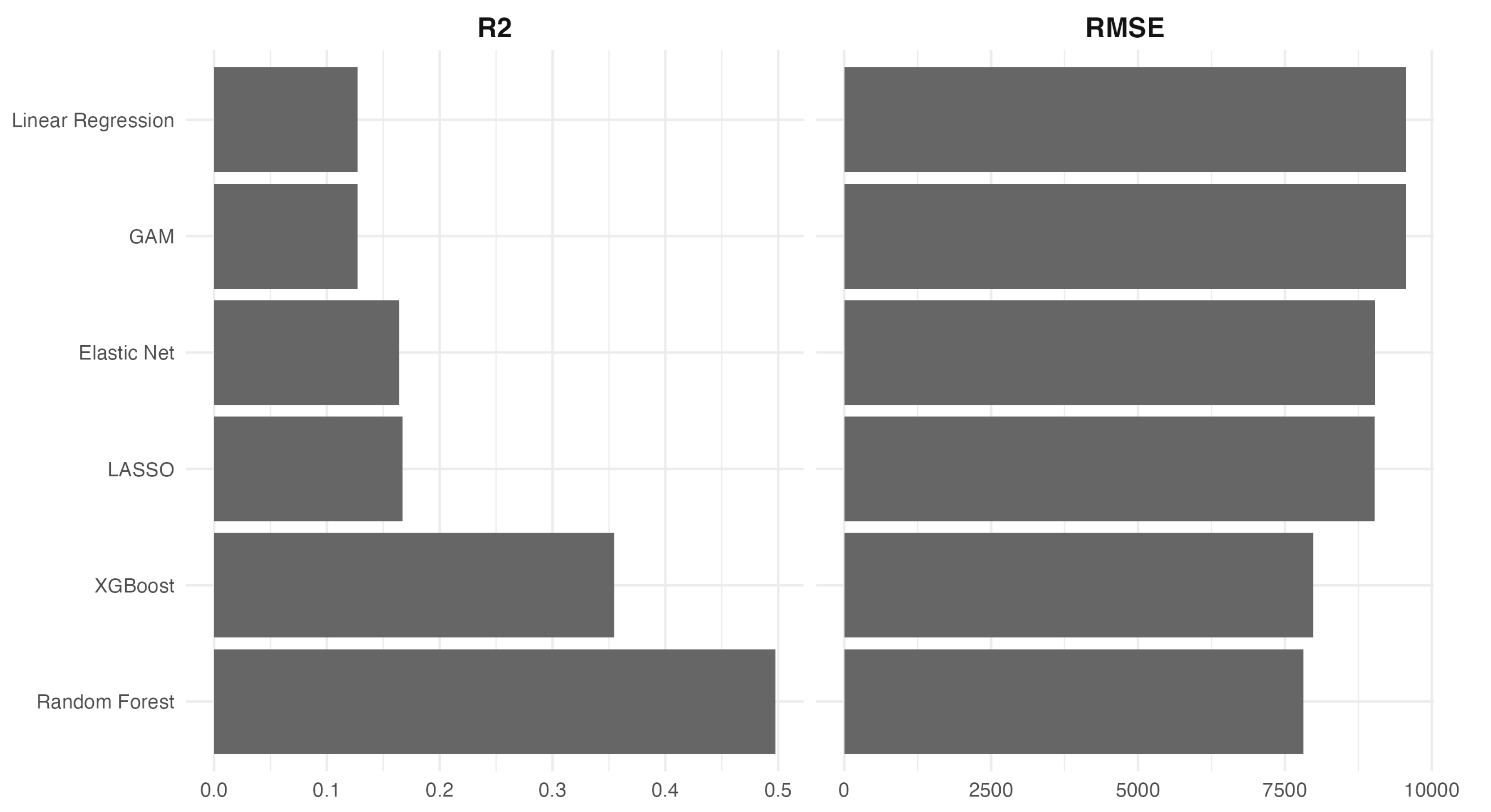

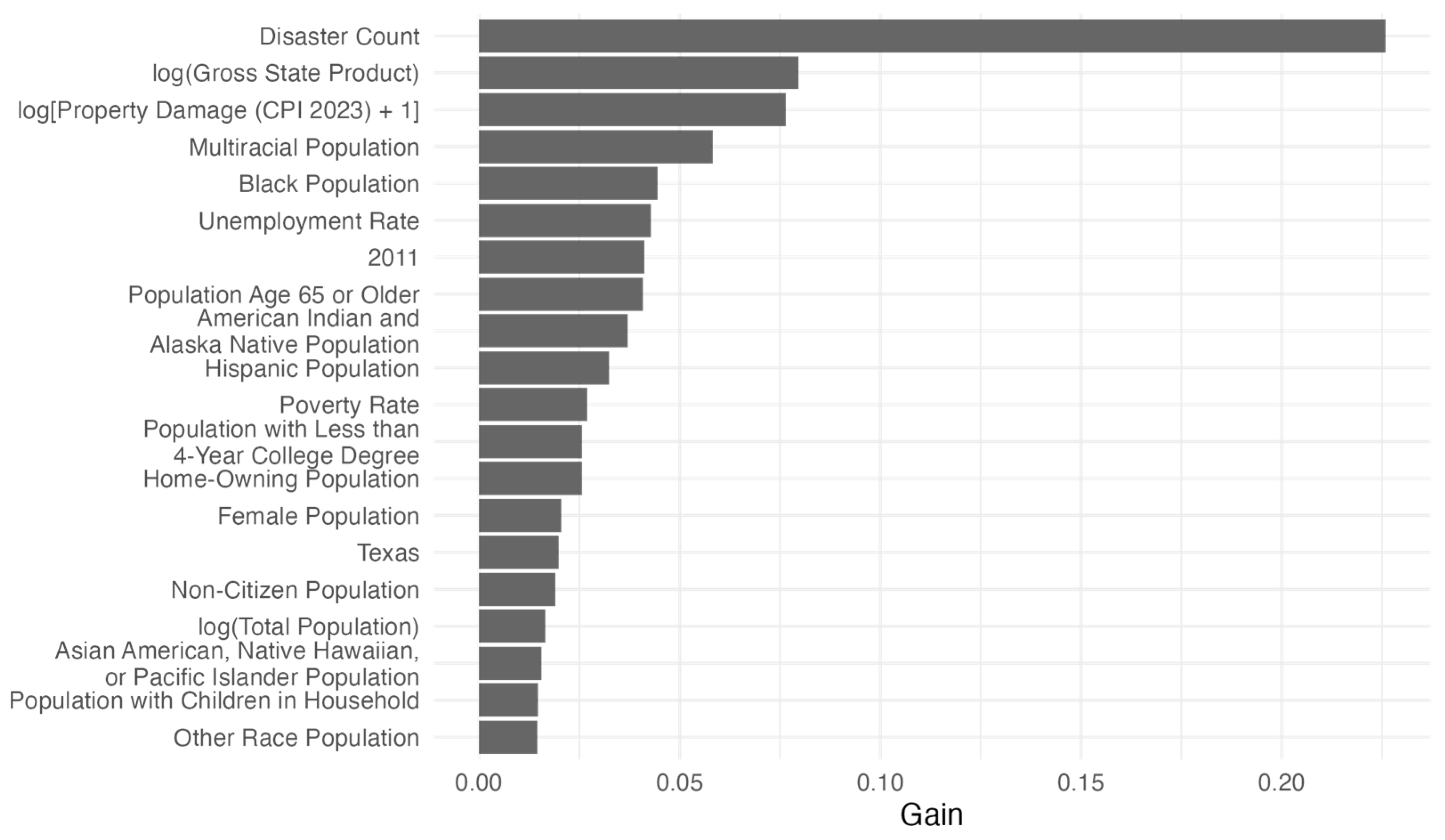

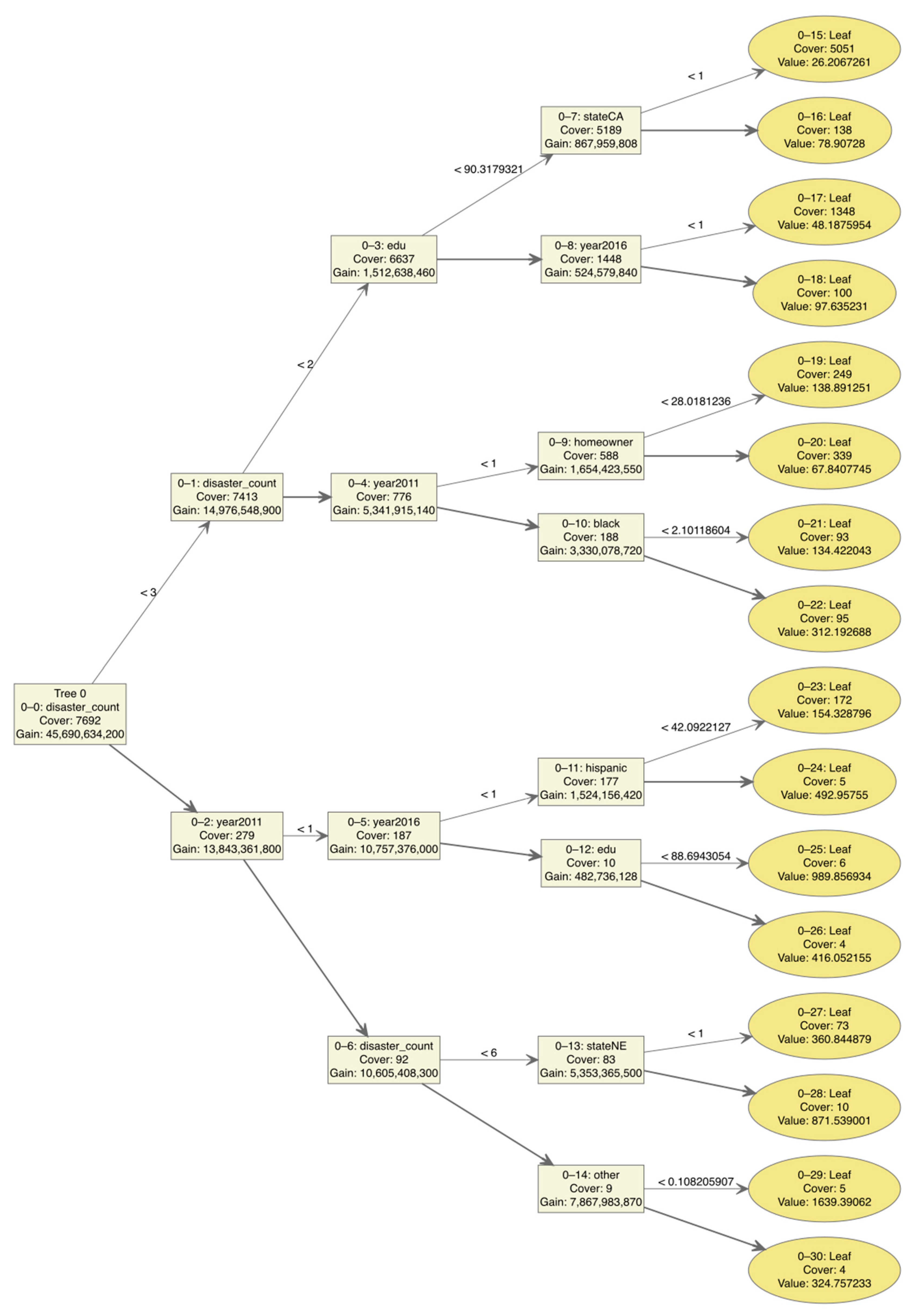

3.3. Machine Learning Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Spearman vs. Baseline | Top Decile Overlap | |

|---|---|---|

| 75 km, 1 year | 0.985 | 0.748 |

| 75 km, 2 years | 0.986 | 0.764 |

| 75 km, 3 years | 0.983 | 0.764 |

| 100 km, 1 year | 0.994 | 0.9 |

| 100 km, 3 years | 0.998 | 0.965 |

| 150 km, 1 year | 0.95 | 0.764 |

| 150 km, 2 years | 0.965 | 0.759 |

| 150 km, 3 years | 0.966 | 0.753 |

Appendix B

| Main | Nearest Neighbors | Kilometers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | 100 | 150 | ||

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| Disaster Count | 4994.898 *** (104.812) | 5046.924 *** (105.915) | 5045.105 *** (105.988) | −70.819 * (38.044) | −69.490 * (38.077) |

| AANHPI | −69.910 (37.940) | −96.618 ** (38.284) | −94.208 ** (38.264) | 0.194 (15.984) | −0.177 (16.000) |

| AIAN | 2.133 (15.942) | −4.498 (16.084) | −3.101 (16.075) | −2.802 (7.708) | −1.470 (7.716) |

| Black | −2.567 (7.688) | −1.008 (7.758) | −1.538 (7.754) | −21.680* (11.786) | −15.128 (11.847) |

| Hispanic | −21.725 (11.716) | −44.785 *** (11.789) | −41.022 *** (11.786) | −140.067 ** (68.268) | −151.635 ** (68.326) |

| Multiracial | −136.112 * (68.099) | −156.900 ** (68.675) | −150.955 ** (68.637) | 438.007 (376.245) | 432.187 (376.538) |

| Other Race | 458.727 (375.335) | 428.075 (378.737) | 441.952 (378.513) | −53.317 (34.159) | −54.525 (34.185) |

| Age 65 or Older | −52.313 (34.075) | −51.512 (34.385) | −49.614 (34.364) | 28.998 (17.796) | 27.020 (17.810) |

| Less than 4-Years of College | 28.902 (17.751) | 37.654 ** (17.925) | 34.729 * (17.914) | 39.901 (38.948) | 35.347 (39.011) |

| Non-Citizen | 44.244 (38.840) | 73.511 * (39.175) | 68.958 * (39.154) | −27.037 (20.422) | −25.877 (20.441) |

| Poverty | −30.751 (20.367) | −16.687 (20.546) | −17.487 (20.534) | 18.052 (42.590) | 11.744 (42.624) |

| Female | 26.417 (42.487) | 12.286 (42.880) | 17.574 (42.856) | −9.480 (36.354) | −2.291 (36.401) |

| Homeowner | −7.312 (36.263) | −14.051 (36.590) | −14.840 (36.569) | −89.696 (66.327) | −98.931 (66.402) |

| Children in Household | −101.694 (66.160) | −75.579 (66.753) | −76.760 (66.714) | 139.168 (93.562) | 146.691 (93.628) |

| log(Total Population) | 141.609 (93.360) | 213.884 ** (94.243) | 201.619 ** (94.191) | 131.090 *** (45.972) | 124.276 *** (46.003) |

| Unemployment | 131.584 ** (45.866) | 142.066 *** (46.278) | 141.136 *** (46.250) | 4999.487 *** (104.593) | 5010.380 *** (104.615) |

| log(Gross State Product) | −1828.480 (1574.036) | −1502.057 (1588.487) | −1559.115 (1587.558) | −1780.553 (1577.809) | −1774.104 (1579.024) |

| Democratic Governor | |||||

| Non-Democrat (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Democrat | 1046.615 *** (196.914) | 1052.074 *** (198.724) | 1058.651 *** (198.603) | 1041.128 *** (197.394) | 1027.789 *** (197.551) |

| Metro Status | |||||

| Metro areas of 1 million or more (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million | −604.716 * (237.200) | −546.661 ** (239.293) | −547.031 ** (239.146) | −610.183 ** (237.738) | −580.643 ** (237.943) |

| Metro areas of fewer than 250,000 | −104.548 (268.935) | −5.547 (271.326) | −17.537 (271.164) | −69.262 (269.563) | −15.536 (269.783) |

| Non-metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population | −201.878 (261.487) | −96.305 (263.722) | −111.055 (263.583) | −198.021 (262.019) | −156.854 (262.208) |

| log(Property Damage + 1) | −6.717 (13.518) | −7.685 (13.640) | −7.321 (13.632) | −6.419 (13.551) | −7.223 (13.562) |

| Intercept | 11,869.054 (17,095.697) | 8798.265 (17,253.029) | 9405.585 (17,242.894) | 12,333.915 (17,136.323) | 12,346.179 (17,149.623) |

| AIC | 260,506.323 | 260,674.036 | 260,663.081 | 260,547.808 | 260,560.129 |

| BIC | 261,146.377 | 261,314.09 | 261,303.135 | 261,187.861 | 261,200.182 |

| Log Likelihood | −130,167.16 | −130,251.02 | −130,245.54 | −130,187.9 | −130,194.06 |

| ρ | 0.336 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.353 | 0.452 |

| Residual Variance | 53,623,809.9 | 54,601,863.8 | 54,537,459.1 | 53,885,391.2 | 53,969,685.9 |

| Main | Nearest Neighbors | Kilometers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | 100 | 150 | |||||||

| β | θ | β | θ | β | θ | β | θ | β | θ | |

| Disaster Count | 5197.283 *** (106.291) | −2789.291 *** (360.917) | 5651.366 *** (109.559) | −2868.246 *** (170.091) | 5651.411 *** (109.879) | −3397.642 *** (202.485) | 5069.603 *** (105.376) | −2376.050 *** (603.092) | 5070.861 *** (105.076) | −3380.173 *** (962.521) |

| AANHPI | −44.819 (50.132) | −105.774 (87.097) | 103.951 * (58.247) | −198.399 *** (67.615) | 80.279 (54.279) | −179.017 *** (68.093) | −65.799 (45.275) | −119.318 (92.518) | −49.392 (42.890) | −220.027 * (121.131) |

| AIAN | 18.387 (19.848) | −60.163 (38.490) | 27.837 (105.296) | −129.926 (117.147) | −14.664 (95.129) | −88.560 (109.948) | 3.160 (20.360) | −1.517 (36.350) | −2.686 (18.924) | 10.701 (46.655) |

| Black | −8.330 (11.910) | 6.627 (18.466) | 67.556 ** (29.485) | −96.643 *** (33.233) | 38.921 (25.453) | −77.224 ** (32.917) | −17.696 * (10.520) | 54.516 ** (22.662) | −14.070 (9.782) | 50.118 (32.481) |

| Hispanic | 2.532 (22.830) | −62.354 * (28.475) | −32.025 (27.391) | 32.862 (28.426) | −12.489 (22.476) | 13.814 (24.095) | −12.391 (23.012) | −28.831 (30.091) | −2.597 (21.042) | −55.438 (34.074) |

| Multiracial | −176.085 * (83.611) | 150.078 (153.974) | −15.462 (34.204) | −45.964 (35.805) | −24.900 (31.438) | −33.118 (34.125) | −179.734 ** (80.384) | 145.294 (177.629) | −205.359 *** (77.776) | 209.658 (230.114) |

| Other Race | 488.658 (391.721) | −563.271 (1082.574) | −118.788 (94.613) | 6.497 (115.587) | −141.447 (94.148) | 39.288 (125.846) | 484.947 (388.888) | −1209.574 (1574.844) | 438.950 (384.951) | −5452.111 * (2859.205) |

| Age 65 or Older | −56.295 (41.594) | 54.094 (86.634) | 706.415 * (423.661) | −1008.755 (668.271) | 737.739 * (428.891) | −1167.566 (726.282) | −69.647 * (38.419) | −1.873 (107.375) | −73.589 ** (37.044) | −165.433 (164.091) |

| Less than 4-Years of College | 5.597 (21.832) | 37.954 (43.529) | 25.406 (39.279) | 33.404 (43.670) | 18.109 (35.143) | 36.233 (41.130) | 13.459 (20.050) | 38.816 (58.586) | 12.946 (19.429) | 109.241 (88.013) |

| Non-Citizen | 12.940 (52.428) | 107.339 (86.090) | 39.138 (72.474) | 72.824 (78.335) | 46.369 (67.887) | 74.276 (78.740) | 23.842 (52.157) | 98.496 (94.066) | 18.754 (48.919) | 146.581 (125.519) |

| Poverty | −45.781 (24.982) | 113.858 * (50.485) | −48.122 (31.126) | 55.835 (36.456) | −47.745 (30.064) | 63.140 * (38.135) | −30.458 (23.720) | 37.706 (61.711) | −23.730 (22.987) | −62.352 (91.359) |

| Female | 41.883 (46.100) | −166.967 (121.593) | −54.967 (64.645) | 38.603 (80.178) | −35.085 (59.060) | 15.804 (80.135) | 24.308 (44.396) | −77.265 (168.935) | 20.057 (43.707) | 184.630 (269.877) |

| Homeowner | 38.879 (42.754) | −97.026 (89.497) | −50.467 (53.751) | 84.179 (64.977) | −60.064 (51.376) | 109.680 (66.921) | −0.440 (39.791) | 51.217 (117.025) | 10.650 (38.785) | 59.565 (185.366) |

| Children in Household | −172.265 * (71.417) | 174.827 (195.235) | −58.518 (80.807) | −52.698 (108.627) | −75.259 (79.574) | −11.903 (118.242) | −118.689 * (69.619) | −280.777 (267.804) | −131.258 * (68.726) | −544.267 (434.138) |

| log(Total Population) | 98.264 (118.144) | 486.705 * (238.940) | 611.361 *** (224.594) | −310.443 (248.624) | 379.598 ** (185.599) | −54.997 (219.873) | 78.166 (108.942) | 987.932 *** (295.795) | 89.243 (105.441) | 769.905 * (443.712) |

| Unemployment | 137.225 ** (50.899) | −129.130 (128.920) | 205.181 *** (52.773) | −105.636 (70.718) | 200.422 *** (52.857) | −129.914 (79.651) | 136.648 *** (49.931) | −119.091 (156.742) | 113.140 ** (48.569) | 217.061 (225.472) |

| log(Gross State Product) | −1727.527 (1581.226) | 171.452 (760.950) | −818.660 (1614.208) | −1832.808 (3421.237) | −736.927 (1610.355) | −5393.370 (4128.130) | −1691.138 (1591.418) | −676.786 (926.739) | −1790.384 (1590.433) | −2207.612 (1377.546) |

| Democratic Governor | ||||||||||

| Non-Democrat (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Democrat | 1031.460 *** (196.574) | −89.261 (1074.730) | 887.480 *** (199.588) | −131.610 (444.795) | 934.310 *** (199.516) | −307.240 (537.862) | 1008.381 *** (197.575) | −542.964 (1446.450) | 1004.364 *** (197.788) | 861.702 (2294.675) |

| Metro Status | ||||||||||

| Metro areas of 1 million or more (reference) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million | −334.708 (397.011) | 114.467 (578.038) | −1451.538 (1027.345) | 1174.191 (1047.881) | −1548.485 ** (767.141) | 1349.020 * (800.145) | −636.902 ** (310.204) | 970.023 (678.253) | −449.817 * (267.013) | 1317.258 (981.910) |

| Metro areas of fewer than 250,000 | −135.745 (417.129) | 704.648 (662.455) | −1692.299 * (967.286) | 1825.810 * (995.643) | −878.930 (756.731) | 1050.473 (802.148) | −141.399 (329.059) | 1671.865 ** (797.029) | 158.900 (294.517) | 1016.165 (1189.490) |

| Non-metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population | −10.134 (375.801) | 332.794 (660.445) | −1296.351 (829.115) | 1377.659 (867.063) | −934.328 (655.664) | 1191.565 * (717.973) | −313.222 (310.893) | 2269.579 ** (884.058) | −104.755 (283.684) | 2902.894 ** (1396.637) |

| log(Property Damage + 1) | −11.165 (13.555) | 11.096 (61.427) | −8.870 (13.510) | −23.941 (27.778) | −9.762 (13.493) | −7.226 (33.140) | −10.341 (13.614) | −25.564 (82.124) | −9.403 (13.609) | 144.560 (125.349) |

| Intercept | 12,366.147 (17,626.566) | 22,855.862 (42,625.090) | 60,166.317 (49,720.086) | 15,793.473 (17,559.226) | 15,345.563 (17,992.076) | |||||

| AIC | 260,521.588 | 260,460.01 | 260,456.262 | 260,599.662 | 260,600.915 | |||||

| BIC | 261,771.925 | 261,688.02 | 261,691.715 | 261,849.999 | 261,851.252 | |||||

| Log Likelihood | −130,092.79 | −130,065.005 | −130,062.131 | −130,131.83 | −130,132.46 | |||||

| ρ | 0.347 | 0.057 | 0.106 | 0.332 | 0.382 | |||||

| Residual Variance | 52,977,052 | 52,985,121.65 | 52,913,033.78 | 53,430,034.1 | 53,489,456.4 | |||||

Appendix C

| Test RMSE | Validation RMSE | Test R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All years | 7214.841 | 5430.338 | 0.466 |

| Exclude 2011 | 8723.187 | 4482.411 | 0.220 |

References

- Drakes, O.; Tate, E.; Rainey, J.; Brody, S. Social vulnerability and short-term disaster assistance in the United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrich, C.T.; Aksha, S.K.; Zhou, Y. Assessing distributive inequities in FEMA’s disaster recovery assistance fund allocation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 74, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.T.; Chang, Y.L. Ecosocial policy and the social risks of climate change: Foundations of the US ecosocial safety net. J. Soc. Policy 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingue, S.J.; Emrich, C.T. Social vulnerability and procedural equity: Exploring the distribution of disaster aid across counties in the United States. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2019, 49, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Jia, H.; Xu, C.; Bockarjova, M.; van Westen, C.; Lombardo, L. Unveiling spatial inequalities: Exploring county-level disaster damages and social vulnerability on public disaster assistance in contiguous US. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.E.; Tate, E. Unequal recovery? Federal resource distribution after a Midwest flood disaster. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, J.; Elliott, J.R. Damages done: The longitudinal impacts of natural hazards on wealth inequality in the United States. Soc. Probl. 2019, 66, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.T.; Nepomnyashcy, L.; Patel, A.S. Is the U.S. ecosocial safety net inequitable? Comparing the Individuals and Households and National Flood Insurance programs. In Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, National Harbor, MD, USA, 21–23 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. WIREs Clim. Change 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, I. Climate change, social policy, and global governance. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 2013, 29, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvilammi, T.; Häikiö, L.; Johansson, H.; Koch, M.; Perkiö, J. Social policy in a climate emergency context: Towards an ecosocial research agenda. J. Soc. Policy 2023, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, B.; Kurtz, L.C. Race, class, ethnicity, and disaster vulnerability. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.D.; Miller, D.S. Continually neglected: Situating natural disasters in the African American experience. J. Black Stud. 2007, 37, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba-Nieves, D.; Santiago-Bartolomei, R. Who gets emergency housing relief? An analysis of FEMA individual assistance data after Hurricane María. Hous. Policy Debate 2023, 33, 1146–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raker, E.J.; Woods, T. Disastrous burdens: Hurricane Katrina, federal housing assistance, and well-being. RSF 2023, 9, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service. FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program (IHP)—Implementation and Considerations for Congress; R47015; CRS: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R47015/R47015.1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Disaster Assistance: Updated FEMA Guidance Could Better Help Communities Apply for Individual Assistance; GAO-25-106768; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-106768 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Individual Assistance Program and Policy Guide, Version 1.1; FP 104-009-03; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_iappg-1.1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Disaster Assistance: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program; GAO-20-503; GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-503 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Simpson, N.P.; Williams, P.A.; Mach, K.J.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Biesbroek, R.; Haasnoot, M.; Segnon, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Musah-Surugu, J.I.; Joe, E.T.; et al. Adaptation to compound climate risks: A systematic global stocktake. iScience 2023, 26, 105926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.R.; Howell, J. Beyond disasters: A longitudinal analysis of natural hazards’ unequal impacts on residential instability. Soc. Forces 2017, 95, 1181–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustan, L.P.; Kahn, M.E.; Rhode, P.W.; Yanguas, M.L. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: A century of data. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 118, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.F. Measuring the labor market impacts of Hurricane Katrina migration: Evidence from Houston, Texas. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varano, S.P.; Schafer, J.A.; Cancino, J.M.; Decker, S.H.; Greene, J.R. A tale of three cities: Crime and displacement after Hurricane Katrina. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupor, B.; McCrory, P.B. A cup runneth over: Fiscal policy spillovers from the 2009 Recovery Act. Econ. J. 2018, 128, 1476–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, A.J.; Gorodnichenko, Y.; Murphy, D. Local Fiscal Multipliers and Fiscal Spillovers in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 25457; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25457/w25457.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Berry, F.S.; Berry, W.D. State lottery adoptions as policy innovations: An event history analysis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1990, 84, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybeck, B.; Berry, W.D.; Siegel, D.A. A strategic theory of policy diffusion via intergovernmental competition. J. Polit. 2011, 73, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, M. Regulating the Lives of Women: Social Welfare Policy from Colonial Times to the Present; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.L.; Lanfranconi, L.M.; Clark, K. Second-order devolution revolution and the hidden structural discrimination? Examining county welfare-to-work service systems in California. J. Poverty 2020, 24, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Order, No. 14180, Council to Assess the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Fed. Regist. 2025, 90, 8743–8745. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/31/2025-02173/council-to-assess-the-federal-emergency-management-agency (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Diggle, P.J. Statistical Analysis of Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Point Patterns, 3rd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. A spatio-temporal kernel density estimation framework for predictive crime hotspot mapping and evaluation. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, G.L. Space–time autoregressive models and forecasting national, regional and state crime rates. Int. J. Forecast. 2013, 29, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Dynamic spatial panels: Models, methods, and inferences. J. Geogr. Syst. 2012, 14, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A machine learning framework for modeling post-disaster recovery time of communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102395. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, C.; Bivand, R. Random forest as a generic framework for predictive modeling of spatial and spatio-temporal variables. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||

| IHP Expenditure per Recipient | The amount of IHP funding per recipient | RI-IHP |

| Independent Variables | ||

| AANHPI Population | Proportion of Asian American and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander population | ACS |

| AIAN Population | Proportion of American Indian or Alaska Native population | ACS |

| Black Population | Proportion of Black population | ACS |

| Hispanic Population | Proportion of Hispanic population | ACS |

| Multiracial Population | Proportion of multiracial population | ACS |

| Other Race Population | Proportion of other race population | ACS |

| Older than Age 65 Population | Proportion of population Older than Age 65 | ACS |

| Less than 4-Years of College Population | Proportion of population with less than 4-years of college | ACS |

| Non-Citizen Population | Proportion of non-citizen population | ACS |

| Poverty Rate | Poverty rate | ACS |

| Female Population | Proportion of female population | ACS |

| Children in Household. Population | Proportion of households with at least one child under the age of 18 | ACS |

| Homeowner Population | Proportion of homeowning population | ACS |

| Total Population (in 100,000’s) | Total population divided by 100,000 | ACS |

| Gross State Product | Gross state product per capita | WRD |

| Democratic Governor | Political affiliation of state Governor | WRD |

| Rurality | Rural–urban continuum codes | USDA |

| Number of Hazards | Number of hazards | SHELDUS |

| Disaster Property Damage | Total property damage | SHELDUS |

| Mean | SD | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHP Expenditure per Recipient | 2534.021 | 8385.775 | 126,23 |

| AANHPI | 1.808 | 3.555 | 126,23 |

| AIAN | 1.16 | 5.283 | 126,23 |

| Black | 11.703 | 15.607 | 126,23 |

| Hispanic | 8.477 | 12.575 | 126,23 |

| Multiracial | 1.935 | 1.792 | 126,23 |

| Other Race | 0.14 | 0.212 | 126,23 |

| White | 74.776 | 20.26 | 126,23 |

| Age 65 or Older | 16.554 | 4.399 | 126,23 |

| Less than 4-Years of College | 84.967 | 6.803 | 126,23 |

| Non-Citizen | 3.047 | 3.651 | 126,23 |

| Poverty | 15.293 | 6.168 | 126,23 |

| Female | 50.313 | 2.039 | 126,23 |

| Homeowner | 27.312 | 4.33 | 126,23 |

| Children in Household | 11.817 | 1.559 | 126,23 |

| Total Population | 193,354 | 512,982.6 | 126,23 |

| Unemployment | 6.473 | 2.802 | 126,23 |

| Gross State Product | 540,176.1 | 581,136.2 | 126,23 |

| Democratic Governor | |||

| Non-Democrat | 7829 (62%) | ||

| Democrat | 4784 (38%) | ||

| Metro Status | |||

| Metro areas of 1 million or more | 2793 (22%) | ||

| Metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million | 2118 (17%) | ||

| Metro areas of fewer than 250,000 | 1556 (12%) | ||

| Non-metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population | 6156 (49%) | ||

| Disaster Count | 1.205 | 0.664 | 12,623 |

| Disaster Property Damage | 72,089,151,320,293.9 | 272,338,196,533,041 | 12,623 |

| STAR | STDM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | θ | |

| Disaster Count | 4994.898 *** (104.812) | 5197.283 *** (106.291) | −2789.291 *** (360.917) |

| AANHPI | −69.910 (37.940) | −44.819 (50.132) | −105.774 (87.097) |

| AIAN | 2.133 (15.942) | 18.387 (19.848) | −60.163 (38.490) |

| Black | −2.567 (7.688) | −8.330 (11.910) | 6.627 (18.466) |

| Hispanic | −21.725 (11.716) | 2.532 (22.830) | −62.354 * (28.475) |

| Multiracial | −136.112 * (68.099) | −176.085 * (83.611) | 150.078 (153.974) |

| Other Race | 458.727 (375.335) | 488.658 (391.721) | −563.271 (1082.574) |

| Age 65 or Older | −52.313 (34.075) | −56.295 (41.594) | 54.094 (86.634) |

| Less than 4-Years of College | 28.902 (17.751) | 5.597 (21.832) | 37.954 (43.529) |

| Non-Citizen | 44.244 (38.840) | 12.940 (52.428) | 107.339 (86.090) |

| Poverty | −30.751 (20.367) | −45.781 (24.982) | 113.858 * (50.485) |

| Female | 26.417 (42.487) | 41.883 (46.100) | −166.967 (121.593) |

| Homeowner | −7.312 (36.263) | 38.879 (42.754) | −97.026 (89.497) |

| Children in Household | −101.694 (66.160) | −172.265 * (71.417) | 174.827 (195.235) |

| Log(Total Population) | 141.609 (93.360) | 98.264 (118.144) | 486.705 * (238.940) |

| Unemployment | 131.584 ** (45.866) | 137.225 ** (50.899) | −129.130 (128.920) |

| Log(Gross State Product) | −1828.480 (1574.036) | −1727.527 (1581.226) | 171.452 (760.950) |

| Democratic Governor | |||

| Non-Democrat (reference) | --- | --- | --- |

| Democrat | 1046.615 *** (196.914) | 1031.460 *** (196.574) | −89.261 (1074.730) |

| Metro Status | |||

| Metro areas of 1 million or more (reference) | --- | --- | --- |

| Metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million | −604.716 * (237.200) | −334.708 (397.011) | 114.467 (578.038) |

| Metro areas of fewer than 250,000 | −104.548 (268.935) | −135.745 (417.129) | 704.648 (662.455) |

| Non-metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population | −201.878 (261.487) | −10.134 (375.801) | 332.794 (660.445) |

| Log(Property Damage + 1) | −6.717 (13.518) | −11.165 (13.555) | 11.096 (61.427) |

| Intercept | 11,869.054 (17,095.697) | 12,366.147 (17,626.566) | |

| AIC | 260,506.323 | 260,521.588 | |

| BIC | 261,146.377 | 261,771.925 | |

| Log Likelihood | −130,167.16 | −130,092.79 | |

| ρ | 0.336 | 0.347 | |

| Residual Variance | 53,623,809.9 | 52,977,052 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, C.T.; Chang, Y.-L. Hotspots of Inequity in Climate Adaptation: Explaining the Stratification of U.S. Ecowelfare Using Space-Time and Machine Learning Analysis. Climate 2025, 13, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120244

Brown CT, Chang Y-L. Hotspots of Inequity in Climate Adaptation: Explaining the Stratification of U.S. Ecowelfare Using Space-Time and Machine Learning Analysis. Climate. 2025; 13(12):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120244

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Christopher Taylor, and Yu-Ling Chang. 2025. "Hotspots of Inequity in Climate Adaptation: Explaining the Stratification of U.S. Ecowelfare Using Space-Time and Machine Learning Analysis" Climate 13, no. 12: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120244

APA StyleBrown, C. T., & Chang, Y.-L. (2025). Hotspots of Inequity in Climate Adaptation: Explaining the Stratification of U.S. Ecowelfare Using Space-Time and Machine Learning Analysis. Climate, 13(12), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120244