Predicting Persistent Forest Fire Refugia Using Machine Learning Models with Topographic, Microclimate, and Surface Wind Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

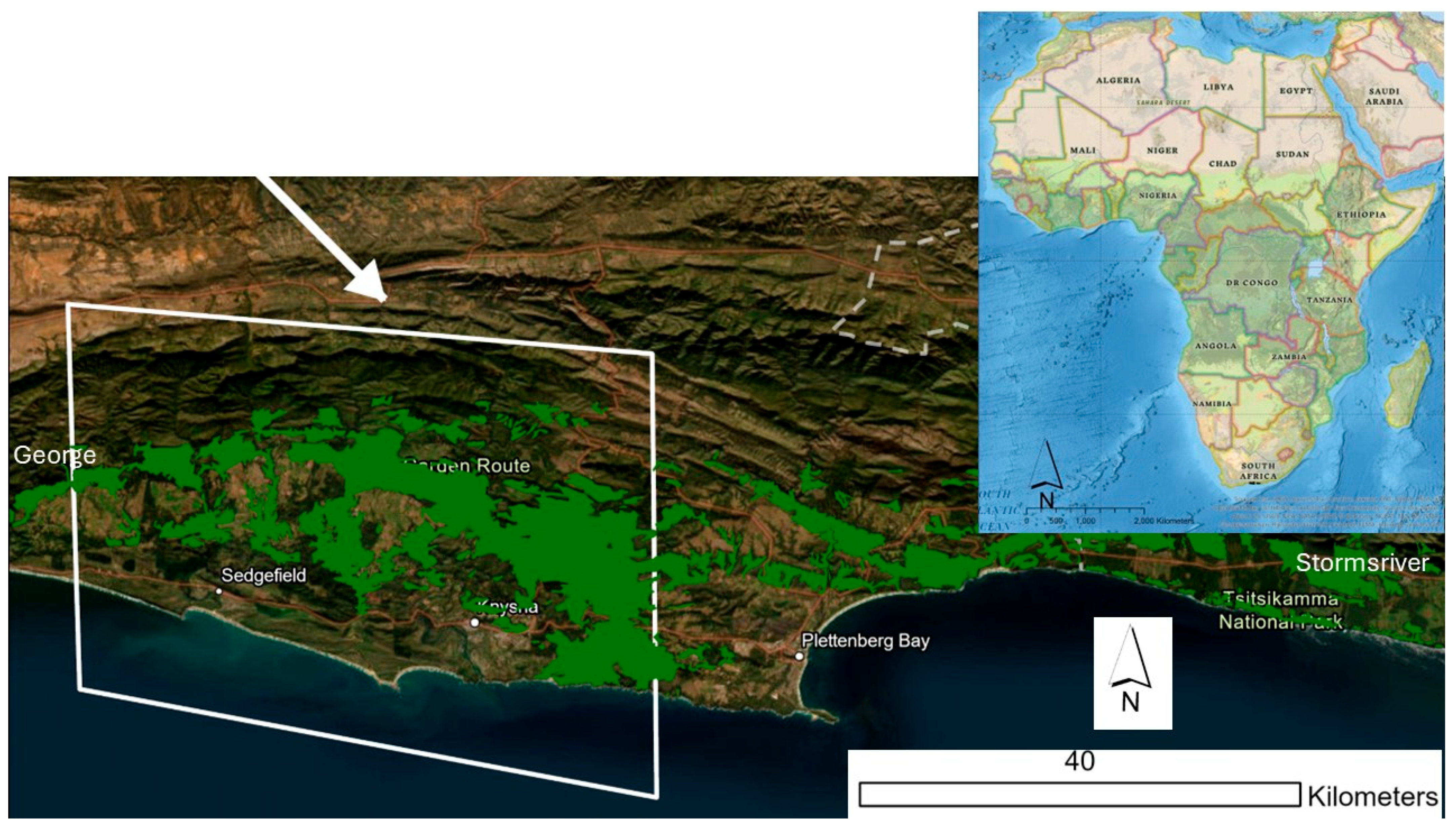

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data for Persistent Forest Fire Refugia

2.3. Data for Predictor Variables

| Variable | Relevance | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation | Higher elevations may be cooler: >moisture <flammable Some sites also see the following: <fuel continuity at highest elevations | [3,4,13,14] |

| Slope | Steeper slopes: >fuel preheating >updrafts >fire spread | [3,9] |

| Aspect | Sun-facing: >solar radiation <moisture Opposite aspect to prevailing fire season wind direction: fire shield | [3,9] |

| Topographic wetness index | Water accumulation: >moisture <flammability | [3] |

| Topographic convergence index | Cold air pooling: >moisture <flammability | [3] |

| Topographic roughness index | Rugged terrain: >volatile surface wind > complex fire behaviour >fire spread | [5] |

| Temperature | Hot areas: <moisture >flammability | |

| Solar irradiation (global, direct, and diffuse) | >heat <moisture >flammability | [4] |

| Wind direction | Prevailing fire wind direction: >heat <moisture >fire spread Lee of prevailing wind direction may experience fire skipping | [46] |

| Wind speed | >wind speed <moisture >flammability and >pre-heating >rate of fire spread | [46] |

2.4. Machine Learning Models

2.5. Model Performance and Evaluation

3. Results

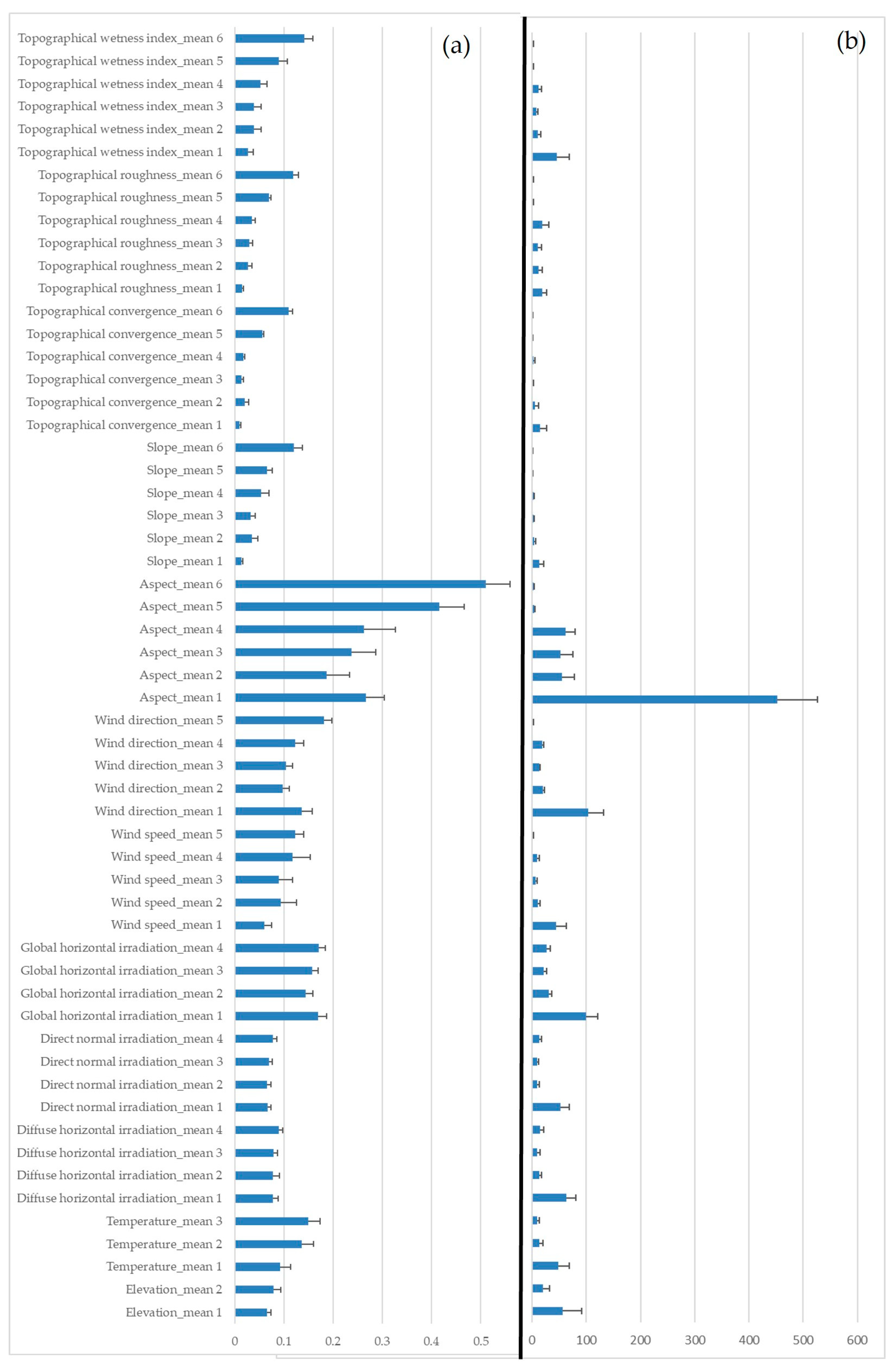

3.1. What Determines Persistent Forest Fire Refugia

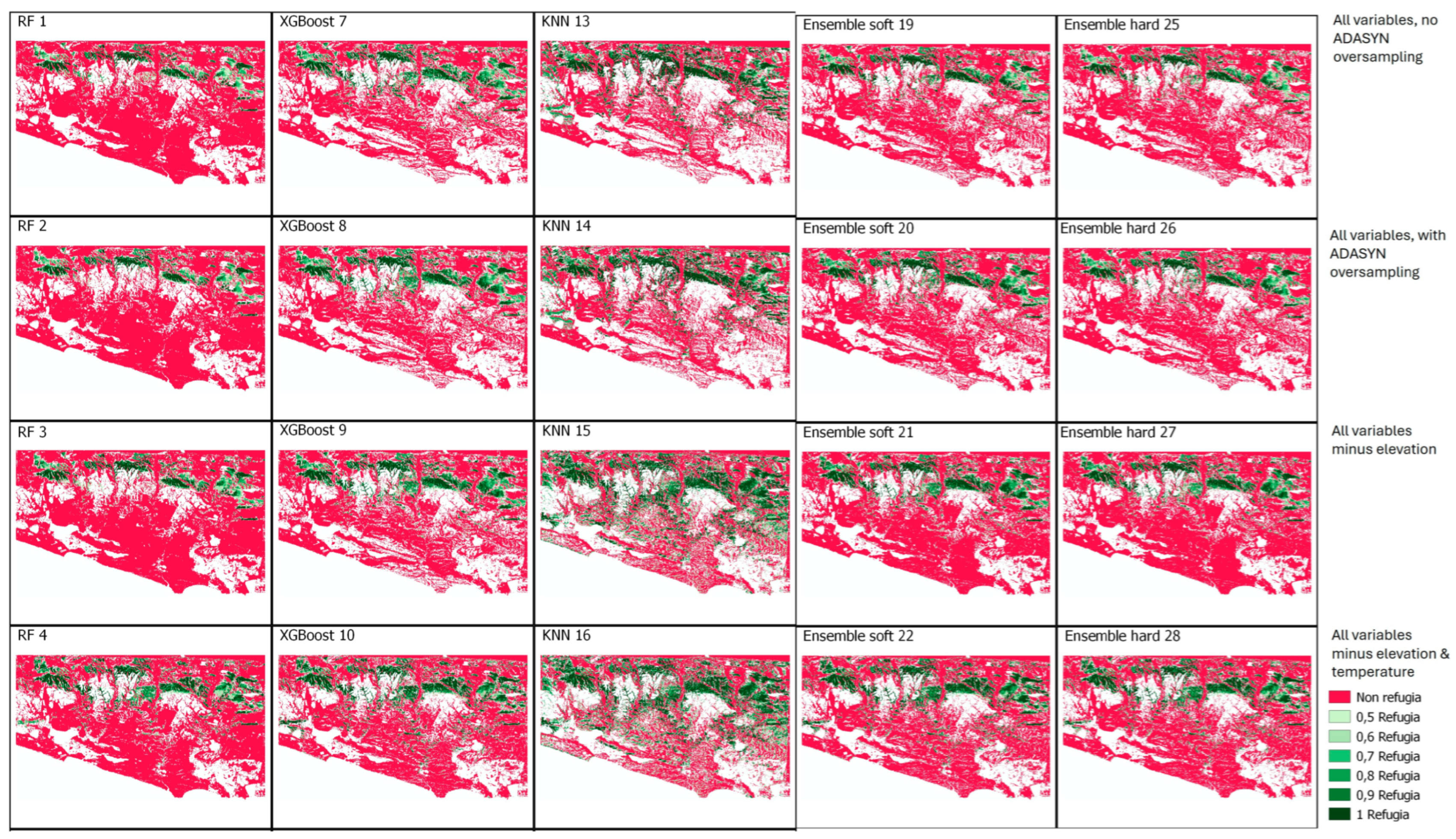

3.2. Model Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. What Determines Forest Fire Refugia

4.2. Methods for Mapping Persistent Forest Fire Refugia

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meddens, A.J.H.; Kolden, C.A.; Lutz, J.A.; Smith, A.M.S.; Cansler, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Meigs, G.W.; Downing, W.M.; Krawchuk, M.A. Fire Refugia: What Are They, and Why Do They Matter for Global Change? BioScience 2018, 68, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Cuesta, R.M.; Gracia, M.; Retana, J. Factors influencing the formation of unburned forest islands within the perimeter of a large forest fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchuk, M.A.; Haire, S.L.; Coop, J.; Parisien, M.A.; Whitman, E.; Chong, G.; Miller, C. Topographic and fire weather controls of fire refugia in forested ecosystems of northwestern North America. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogeau, M.-P.; Barber, Q.E.; Parisien, M.-A. Effect of Topography on Persistent Fire Refugia of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Forests 2018, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, C.J. Bergwind Fires and the Location Pattern of Forest Patches in the Southern Cape Landscape, South-Africa. J. Biogeogr. 1994, 21, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddey, B.L.; Baard, J.A.; Kraaij, T. Verification of the differenced Normalised Burn Ratio (dNBR) as an index of fire severity in Afrotemperate Forest. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 146, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodman, K.C.; Davis, K.T.; Parks, S.A.; Chapman, T.B.; Coop, J.D.; Iniguez, J.M.; Roccaforte, J.P.; Meador, A.J.S.; Springer, J.D.; Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; et al. Refuge-yeah or refuge-nah? Predicting locations of forest resistance and recruitment in a fiery world. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 7029–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, R.C. A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels; USDA Forest Services Research Paper; Research Paper INT-115; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1972; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Penman, T.D.; Smith, A.; Burton, J.; Heap, A.; McColl-Gausden, S.C.; Najera-Umana, J.; Gordon, F.; Holyland, B.; Marshall, E. What does it take to survive? An expert elicitation approach to understanding the drivers of fire Refugia occurrence and persistence. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 308, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, A.; Oliver, C.; Hessburg, P.; Everett, R. Predicting late-successional fire refugia pre-dating European settlement in the Wenatchee Mountains. For. Ecol. Manag. 1997, 95, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafer, C.J.; Noonan, M.; Macnaught, E. The post-fire measurement of fire severity and intensity in the Christmas 2001 Sydney wildfires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2004, 13, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.J.; DeGloria, S.D.; Elliot, R. A Terrain Ruggedness Index that Quantifies Topographic Heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 1999, 5, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rogeau, M.P.; Armstrong, G.W. Quantifying the effect of elevation and aspect on fire return intervals in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 384, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azedou, A.; Lahssini, S.; Khattabi, A.; Meliho, M.; Rifai, N. A Methodological Comparison of Three Models for Gully Erosion Susceptibility Mapping in the Rural Municipality of El Faid (Morocco). Sustainability 2021, 13, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manders, P.T. Fire and Other Variables as Determinants of Forest Fynbos Boundaries in the Cape-Province. J. Veg. Sci. 1990, 1, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetsee, C.; Bond, W.J.; Wigley, B.J. Forest and fynbos are alternative states on the same nutrient poor geological substrate. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 101, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, M.D.; Power, S.C.; Belev, A.; Gillson, L.; Bond, W.J.; Hoffman, M.T.; Hedin, L.O. Are forest-shrubland mosaics of the Cape Floristic Region an example of alternate stable states? Ecography 2019, 42, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Z.; Bond, W.J.; Sheffer, E.; Cramer, M.D.; West, A.G.; Allsopp, N.; February, E.C.; Chimphango, S.; Ma, Z.Q.; Slingsby, J.A.; et al. Biome boundary maintained by intense belowground resource competition in world’s thinnest-rooted plant community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117514119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucina, L.; Geldenhuys, C. Afrotemperate, subtropical and azonal forests. In The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland; Rutherford, L.M.M., Ed.; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; pp. 586–615. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G. Alternative fire-driven vegetation states. J. Veg. Sci. 2015, 26, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Bond, W.J. Humboldt and the reinvention of nature. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddey, B.; Baard, J.A.; Vhengani, L.; Kraaij, T. The effect of adjacent vegetation on fire severity in Afrotemperate forest along the southern Cape coast of South Africa. South For. 2021, 83, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Midgley, G.F.; Woodward, F.I. What controls South African vegetation—Climate or fire? S. Afr. J. Bot. 2003, 69, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilgen, B.W.; Higgins, K.B.; Bellstedt, D.U. The role of vegetation structure and fuel chemistry in excluding fire from forest patches in the fire-prone fynbos shrublands of South Africa. J. Ecol. 1990, 78, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson LH, C.M. The influence of fire on a southern cape mountain forest. S. Afr. For. J. 2001, 191, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, T.; Kraaij, T.; Grobler, B.A.; Cowling, R.M. Canopy plant composition and structure of Cape subtropical dune thicket are predicted by the levels of fire exposure. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, J.; Tyson, P.O. A preliminary assessment of Podocarpus falcatus in dendrochronological and dendroclimatological studies in the Witelsbos Forest Reserve. S. Afr. For. J. 1979, 111, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij, T.; Baard, J.; Schutte-Vlok, A.L. Plant response to the fire regime (1970–2023) in a fynbos World Heritage Site: Ecological indicators for fire management. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij, T.; Baard, J.A.; Cowling, R.M.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Das, S. Historical fire regimes in a poorly understood, fire-prone ecosystem: Eastern coastal fynbos. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, L.J.; Chase, B.M.; Wündsch, M.; Kirsten, K.L.; Chevalier, M.; Mäusbacher, R.; Meadows, M.E.; Haberzettl, T. A high-resolution record of Holocene climate and vegetation dynamics from the southern Cape coast of South Africa: Pollen and microcharcoal evidence from Eilandvlei. J. Quat. Sci. 2018, 33, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J. Cape Plants: A Conspectus of the Cape Flora of South Africa; National Botanical Institute: Pretoria, South Africa; Missouri Botanical Garden: St Louis, MO, USA, 2000; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys, C.J.; Moll, E.J.; Swart, R.C. Evergreen forests in South Africa—Their composition, biogeography, ecological dynamics and sustainable use management. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2026, 188, 63–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, C.J. Composition and Dynamics of Plant Communities in the Southern Cape Forests; CSIR, Division of Forest Science and Technology: Pretoria, South Africa, 1993; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys, C.J. The Management of the Southern Cape Forests. S. Afr. For. J. 1982, 121, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij, T.; Cowling, R.M.; van Wilgen, B.W. Lightning and fire weather in eastern coastal fynbos shrublands: Seasonality and long-term trends. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Boschetti, L.; Roy, D.P.; Humber, M.L.; Justice, C.O. The Collection 6 MODIS burned area mapping algorithm and product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA JPL. NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 1 arc Second [Data Set]. 2013. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-srtmgl1-003 (accessed on 4 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Elkhrachy, I. Vertical accuracy assessment for SRTM and ASTER Digital Elevation Models: A case study of Najran city, Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimbye, Z.E.; de Clercq, W.P.; Van Niekerk, A. An evaluation of digital elevation models (DEMs) for delineating land components. Geoderma 2014, 213, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggel, C.; Schneider, D.; Miranda, P.J.; Delgado Granados, H.; Kääb, A. Evaluation of ASTER and SRTM DEM data for lahar modeling: A case study on lahars from Popocatépetl Volcano, Mexico. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 170, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass Development Team. Geographic Resources Analysis Support System (GRASS) Software, Version 8.4; Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2024.

- Solargis. Solar Resource Map; Solargis: Singapore, 2021; Available online: https://solargis.com/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Biljecki, F.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Ledoux, H.; Stoter, J. Propagation of positional error in 3D GIS: Estimation of the solar irradiation of building roofs. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 2269–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, S. The Influence of Topographical Variability on Wildfire Occurrence and Propagation; Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morvan, D. Physical Phenomena and Length Scales Governing the Behaviour of Wildfires: A Case for Physical Modelling. Fire Technol. 2011, 47, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.J.; McRae, R.H.; Wilkes, S.R. Wind–terrain effects on the propagation of wildfires in rugged terrain: Fire channelling. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.; Kleyn, L.; Van Den Dool, R.; Burgess, M.; Vhengani, L.; Steenkamp, K.; Wessels, K. The Elandskraal Fire, Knysna: A Data Driven Analysis; CSIR Meraka Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, C.A.; Chudzinska, M.; Larsen-Gray, A.; Pollock, C.J.; Sells, S.N.; White, P.J.C.; Berger, U. From theory to practice in pattern-oriented modelling: Identifying and using empirical patterns in predictive models. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1868–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithani, M.B.; Sanyal, S.; Shukla, A.K. Bilinear and Bicubic Interpolations for Image Presentation of Mechanical Stress and Temperature Distribution. Power Eng. Eng. Thermophys. 2022, 1, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.T.; Wang, L.M.; Wu, G.S. LIP: Local Importance-based Pooling. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2019), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3354–3363. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, R.; Bansal, C.; Kang, M.Y.; Blau, T.; Agarwal, V.; Singh, P.; Wilson, L.O.W.; Vasan, S. Unsupervised machine learning framework for discriminating major variants of concern during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Garcia, E.A.; Li, S. ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. IEEE Int. Jt. Conf. Neural Netw. 2008, 2008, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Er, M.J.; Fareed, M.M.S.; Zikria, S.; Mahmood, S.; He, J.; Asad, M.; Jilani, S.F.; Aslam, M. DAD-Net: Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease Using ADASYN Oversampling Technique and Optimized Neural Network. Molecules 2022, 27, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.; Carneiro, D.; Novais, P. evoRF: An Evolutionary Approach to Random Forests. Stud. Comput. Intell. 2020, 868, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ishwaran, H. Random forests for genomic data analysis. Genomics 2012, 99, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In KDD 16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Krishnapuram, B., Shah, M., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Georganos, S.; Grippa, T.; Vanhuysse, S.; Lennert, M.; Shimoni, M.; Wolff, E. Very High Resolution Object-Based Land Use-Land Cover Urban Classification Using Extreme Gradient Boosting. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.L.; Peng, Y.X.; Wu, L.T.; Guo, X.Y.; Wang, X.B.; Kong, X.Q. Application of Machine Learning Techniques to Predict the Occurrence of Distraction-affected Crashes with Phone-Use Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Noi, P.; Kappas, M. Comparison of Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbor, and Support Vector Machine Classifiers for Land Cover Classification Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Sensors 2017, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.B.; Kanagachidambaresan, G.R. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. In Programming with TensorFlow; EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing; Prakash, K.B., Kanagachidambaresan, G.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 105–144. [Google Scholar]

- Barzani, A.R.; Pahlavani, P.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Gholamnia, K.; Ghamisi, P. Evaluating the Impact of Recursive Feature Elimination on Machine Learning Models for Predicting Forest Fire-Prone Zones. Fire Ecol. 2024, 7, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhang, F. Predicting Forest Fire Area Growth Rate Using an Ensemble Algorithm. Forests 2024, 15, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantithamthavorn, C.; McIntosh, S.; Hassan, A.E.; Matsumoto, K. The Impact of Automated Parameter Optimization on Defect Prediction Models. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2019, 45, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.A.; Polley, E.C.; Briggs, F.B.S. Random Forests for Genetic Association Studies. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. 2011, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraaij, T.; Baard, J.A.; Arndt, J.; Vhengani, L.; van Wilgen, B.W. An assessment of climate, weather, and fuel factors influencing a large, destructive wildfire in the Knysna region, South Africa. Fire Ecol. 2018, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Search Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | |||||

| Out-of-bag score | TRUE | ||||

| N estimators | 50 | 100 | 200 | 500 | |

| Max features | sqrt | log2 | |||

| Max depth | none | 10 | 20 | 30 | |

| Min samples split | 2 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Min samples leaf | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| XGBoost | |||||

| Parameter search values | |||||

| Eta (Learning rate) | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| N estimators | 50 | 100 | 200 | 1500 | |

| Max depth | 3 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Reg_alpha (Lasso regression) | 0 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Reg_lambda (Ridge regression) | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | |

| KNN | |||||

| Parameter search values | |||||

| N neighbours | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| Weights | uniform | distance | |||

| Metric | Euclidean | Manhattan | Minkowski | ||

| Method | Experiment Number | Elevation | Temperature | Diffuse horizontal Irradiation | Direct Normal Irradiation | Global Horizontal Irradiation | Wind Speed | Wind Direction | Aspect | Slope | Topographical Convergence | Topographical Roughness | Topographical Wetness Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 1 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| 3 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||

| 4 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |||

| 5 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| XGBoost | 7 | 56.27 | 48.56 | 63.49 | 52.52 | 99.87 | 44.88 | 103.19 | 452.29 | 13.23 | 14.88 | 18.83 | 45.64 |

| 8 | 19.66 | 13.67 | 13.07 | 10.02 | 30.49 | 10.33 | 19.57 | 55.02 | 3.99 | 5.32 | 12.69 | 10.44 | |

| 9 | 9.61 | 9.94 | 9.02 | 21.65 | 7.07 | 13.28 | 52.39 | 2.29 | 1.52 | 11.27 | 7.92 | ||

| 10 | 14.96 | 13.08 | 27.28 | 9.54 | 18.84 | 62.25 | 3.21 | 3.19 | 19.18 | 12.26 | |||

| 11 | 0.83 | 1.72 | 4.62 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 1.06 | 0.92 | ||||||

| 12 | 2.31 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.67 |

| Method | Experiment_No | Accuracy_Mean | Accuracy_Std | Accuracy_CI_Low | Accuracy_CI_High | Precision_Mean | Precision_Std | Precision_CI_Low | Precision_CI_High | Recall_Mean | Recall_Std | Recall_CI_Low | Recall_CI_High | F1_Mean | F1_Std | F1_CI_Low | F1_CI_High | OOB_Mean | OOB_Std | OOB_CI_Low | OOB_CI_High | AUC_ROC_Mean | AUC_ROC_Std | AUC_ROC_CI_Low | AUC_ROC_CI_High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 1 | 0.810 | 0.097 | 0.750 | 0.870 | 0.796 | 0.146 | 0.706 | 0.886 | 0.624 | 0.257 | 0.464 | 0.783 | 0.654 | 0.185 | 0.540 | 0.769 | 0.997 | 0.001 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.902 | 0.068 | 0.861 | 0.944 |

| RF | 2 | 0.813 | 0.088 | 0.758 | 0.867 | 0.794 | 0.142 | 0.706 | 0.882 | 0.623 | 0.228 | 0.481 | 0.764 | 0.660 | 0.166 | 0.557 | 0.763 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.895 | 0.067 | 0.853 | 0.936 |

| RF | 3 | 0.822 | 0.082 | 0.771 | 0.873 | 0.788 | 0.141 | 0.700 | 0.875 | 0.664 | 0.229 | 0.522 | 0.806 | 0.685 | 0.157 | 0.587 | 0.782 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.908 | 0.058 | 0.872 | 0.944 |

| RF | 4 | 0.834 | 0.045 | 0.806 | 0.862 | 0.762 | 0.163 | 0.661 | 0.863 | 0.707 | 0.136 | 0.623 | 0.791 | 0.716 | 0.110 | 0.648 | 0.784 | 0.993 | 0.002 | 0.992 | 0.995 | 0.914 | 0.028 | 0.896 | 0.932 |

| RF | 5 | 0.831 | 0.030 | 0.812 | 0.849 | 0.716 | 0.152 | 0.622 | 0.810 | 0.773 | 0.115 | 0.702 | 0.845 | 0.729 | 0.096 | 0.670 | 0.789 | 0.965 | 0.004 | 0.963 | 0.968 | 0.914 | 0.027 | 0.898 | 0.931 |

| RF | 6 | 0.806 | 0.043 | 0.779 | 0.833 | 0.662 | 0.157 | 0.564 | 0.759 | 0.836 | 0.067 | 0.794 | 0.878 | 0.723 | 0.094 | 0.665 | 0.782 | 0.891 | 0.014 | 0.882 | 0.900 | 0.894 | 0.031 | 0.875 | 0.913 |

| XGboost | 7 | 0.821 | 0.089 | 0.766 | 0.876 | 0.766 | 0.129 | 0.686 | 0.846 | 0.685 | 0.238 | 0.537 | 0.833 | 0.692 | 0.156 | 0.595 | 0.789 | 0.905 | 0.058 | 0.869 | 0.940 | ||||

| XGboost | 8 | 0.820 | 0.084 | 0.768 | 0.871 | 0.761 | 0.131 | 0.680 | 0.842 | 0.682 | 0.220 | 0.546 | 0.819 | 0.691 | 0.145 | 0.601 | 0.782 | 0.897 | 0.061 | 0.859 | 0.935 | ||||

| XGboost | 9 | 0.825 | 0.082 | 0.774 | 0.876 | 0.755 | 0.128 | 0.676 | 0.834 | 0.707 | 0.223 | 0.569 | 0.845 | 0.703 | 0.145 | 0.614 | 0.793 | 0.898 | 0.068 | 0.856 | 0.940 | ||||

| XGboost | 10 | 0.843 | 0.039 | 0.819 | 0.868 | 0.758 | 0.152 | 0.664 | 0.852 | 0.743 | 0.119 | 0.670 | 0.817 | 0.739 | 0.101 | 0.676 | 0.801 | 0.920 | 0.031 | 0.902 | 0.939 | ||||

| XGboost | 11 | 0.819 | 0.023 | 0.805 | 0.833 | 0.709 | 0.153 | 0.614 | 0.804 | 0.734 | 0.107 | 0.668 | 0.801 | 0.707 | 0.092 | 0.650 | 0.764 | 0.895 | 0.027 | 0.879 | 0.912 | ||||

| XGboost | 12 | 0.796 | 0.036 | 0.774 | 0.819 | 0.662 | 0.156 | 0.565 | 0.758 | 0.775 | 0.062 | 0.737 | 0.814 | 0.699 | 0.087 | 0.645 | 0.753 | 0.867 | 0.030 | 0.848 | 0.885 | ||||

| KNN | 13 | 0.812 | 0.043 | 0.785 | 0.839 | 0.709 | 0.163 | 0.608 | 0.810 | 0.741 | 0.133 | 0.659 | 0.823 | 0.703 | 0.092 | 0.646 | 0.761 | 0.842 | 0.045 | 0.814 | 0.869 | ||||

| KNN | 14 | 0.804 | 0.039 | 0.780 | 0.827 | 0.685 | 0.171 | 0.579 | 0.791 | 0.758 | 0.123 | 0.681 | 0.834 | 0.698 | 0.101 | 0.635 | 0.761 | 0.822 | 0.042 | 0.796 | 0.848 | ||||

| KNN | 15 | 0.823 | 0.026 | 0.807 | 0.839 | 0.693 | 0.158 | 0.595 | 0.791 | 0.792 | 0.100 | 0.730 | 0.854 | 0.726 | 0.106 | 0.660 | 0.791 | 0.844 | 0.032 | 0.824 | 0.863 | ||||

| KNN | 16 | 0.821 | 0.027 | 0.804 | 0.837 | 0.690 | 0.158 | 0.592 | 0.788 | 0.792 | 0.100 | 0.730 | 0.854 | 0.724 | 0.105 | 0.659 | 0.789 | 0.842 | 0.031 | 0.823 | 0.861 | ||||

| KNN | 17 | 0.799 | 0.027 | 0.782 | 0.815 | 0.656 | 0.151 | 0.562 | 0.750 | 0.786 | 0.087 | 0.732 | 0.839 | 0.701 | 0.091 | 0.644 | 0.757 | 0.834 | 0.023 | 0.820 | 0.849 | ||||

| KNN | 18 | 0.778 | 0.036 | 0.756 | 0.801 | 0.630 | 0.153 | 0.535 | 0.725 | 0.782 | 0.058 | 0.746 | 0.818 | 0.682 | 0.091 | 0.626 | 0.739 | 0.828 | 0.024 | 0.813 | 0.843 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 19 | 0.818 | 0.087 | 0.763 | 0.872 | 0.771 | 0.137 | 0.687 | 0.856 | 0.671 | 0.234 | 0.526 | 0.816 | 0.683 | 0.154 | 0.588 | 0.779 | 0.909 | 0.056 | 0.874 | 0.944 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 20 | 0.823 | 0.078 | 0.774 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0.145 | 0.672 | 0.852 | 0.695 | 0.212 | 0.564 | 0.827 | 0.698 | 0.140 | 0.611 | 0.785 | 0.906 | 0.056 | 0.871 | 0.941 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 21 | 0.835 | 0.070 | 0.792 | 0.878 | 0.764 | 0.132 | 0.682 | 0.845 | 0.726 | 0.197 | 0.603 | 0.848 | 0.721 | 0.127 | 0.643 | 0.800 | 0.919 | 0.040 | 0.894 | 0.944 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 22 | 0.843 | 0.036 | 0.821 | 0.865 | 0.745 | 0.163 | 0.644 | 0.846 | 0.765 | 0.117 | 0.692 | 0.837 | 0.741 | 0.111 | 0.673 | 0.810 | 0.919 | 0.026 | 0.903 | 0.935 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 23 | 0.825 | 0.027 | 0.809 | 0.842 | 0.702 | 0.154 | 0.606 | 0.798 | 0.780 | 0.108 | 0.714 | 0.847 | 0.725 | 0.096 | 0.666 | 0.785 | 0.908 | 0.026 | 0.892 | 0.924 | ||||

| EnsembleS | 24 | 0.803 | 0.043 | 0.776 | 0.830 | 0.658 | 0.158 | 0.560 | 0.756 | 0.833 | 0.065 | 0.793 | 0.873 | 0.720 | 0.097 | 0.660 | 0.780 | 0.890 | 0.030 | 0.872 | 0.908 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 25 | 0.814 | 0.092 | 0.757 | 0.871 | 0.777 | 0.140 | 0.690 | 0.864 | 0.653 | 0.240 | 0.504 | 0.802 | 0.673 | 0.163 | 0.572 | 0.774 | 0.909 | 0.056 | 0.874 | 0.944 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 26 | 0.820 | 0.082 | 0.769 | 0.871 | 0.771 | 0.141 | 0.683 | 0.859 | 0.672 | 0.219 | 0.536 | 0.807 | 0.687 | 0.147 | 0.596 | 0.778 | 0.906 | 0.056 | 0.871 | 0.941 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 27 | 0.831 | 0.075 | 0.785 | 0.877 | 0.771 | 0.134 | 0.688 | 0.854 | 0.708 | 0.212 | 0.577 | 0.839 | 0.711 | 0.137 | 0.626 | 0.796 | 0.919 | 0.040 | 0.894 | 0.944 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 28 | 0.841 | 0.038 | 0.818 | 0.865 | 0.750 | 0.165 | 0.648 | 0.853 | 0.750 | 0.123 | 0.673 | 0.826 | 0.736 | 0.113 | 0.665 | 0.806 | 0.919 | 0.026 | 0.903 | 0.935 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 29 | 0.828 | 0.028 | 0.810 | 0.845 | 0.708 | 0.155 | 0.612 | 0.804 | 0.775 | 0.111 | 0.706 | 0.844 | 0.726 | 0.099 | 0.665 | 0.787 | 0.908 | 0.026 | 0.892 | 0.924 | ||||

| EnsembleH | 30 | 0.805 | 0.045 | 0.777 | 0.833 | 0.659 | 0.159 | 0.560 | 0.758 | 0.840 | 0.063 | 0.800 | 0.879 | 0.723 | 0.099 | 0.662 | 0.785 | 0.890 | 0.030 | 0.872 | 0.908 | ||||

| Mean | 0.819 | 0.728 | 0.736 | 0.706 | 0.974 | 0.891 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Std dev | 0.014 | 0.048 | 0.059 | 0.022 | 0.039 | 0.030 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 0.778 | 0.630 | 0.623 | 0.654 | 0.891 | 0.822 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Max | 0.843 | 0.796 | 0.840 | 0.741 | 0.998 | 0.920 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christ, S.; Kraaij, T.; Geldenhuys, C.J.; de Klerk, H.M. Predicting Persistent Forest Fire Refugia Using Machine Learning Models with Topographic, Microclimate, and Surface Wind Variables. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120480

Christ S, Kraaij T, Geldenhuys CJ, de Klerk HM. Predicting Persistent Forest Fire Refugia Using Machine Learning Models with Topographic, Microclimate, and Surface Wind Variables. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120480

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrist, Sven, Tineke Kraaij, Coert J. Geldenhuys, and Helen M. de Klerk. 2025. "Predicting Persistent Forest Fire Refugia Using Machine Learning Models with Topographic, Microclimate, and Surface Wind Variables" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120480

APA StyleChrist, S., Kraaij, T., Geldenhuys, C. J., & de Klerk, H. M. (2025). Predicting Persistent Forest Fire Refugia Using Machine Learning Models with Topographic, Microclimate, and Surface Wind Variables. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120480