Open-Loop Characterisation of Soft Actuator Pressure Regulated by Pulse-Driven Solenoid Valve

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The development of a dynamic model to describe the pressure at the output of solenoid valves;

- A comparative analysis of linearity of system behaviour when actuated by four types of pulse modulator, namely PWM, IPFM, IIPFM, and M;

- A method of tuning pulse modulators by optimising the linearity of the valve;

- The validation of analytical results by means of open-loop experiments.

2. Soft Pneumatic System

- A compressor (SGS SC50V), used as the source of pressurized air to the system.

- The pressure regulator (SMC ITV1030-31F2N3), that serves to achieve a desired constant pressure during the experiments.

- A 2-litre tank, utilized as an air reservoir to mitigate the small oscillations caused by the regulator and reduce the effect of momentary intense consumption of air.

- The 3/2 solenoid valve (SMC V114-5G-M5).

- The SPA (manufactured in the laboratory), consisting of a dual-cavity bellows-type bending actuator with a total internal volume of 28 ml and external dimensions of cm. The actuator was fabricated using Dragon Skin 20 silicone. Further details on the SPA design can be found in [18].

- A PC with MATLAB R2020b software that serves to program the controller unit and monitor the state of the platform with data from sensors.

- A dSpace processor (MicroLabBox I), i.e., a real-time computing unit that runs the control algorithm, and also serves as digital and analogue I/O board.

- A driver (MD10C R3), that actuates on the solenoid valve by converting the pulse train containing the control signal information at the logic level to the rated voltage of the solenoid valve.

- Two pressure sensors (MPX5100DP) with an accuracy of % of the full-scale (1 bar), placed at the entrance of the valve and at the output, respectively.

3. Modelling of the Soft Pneumatic System

3.1. Theoretical Model

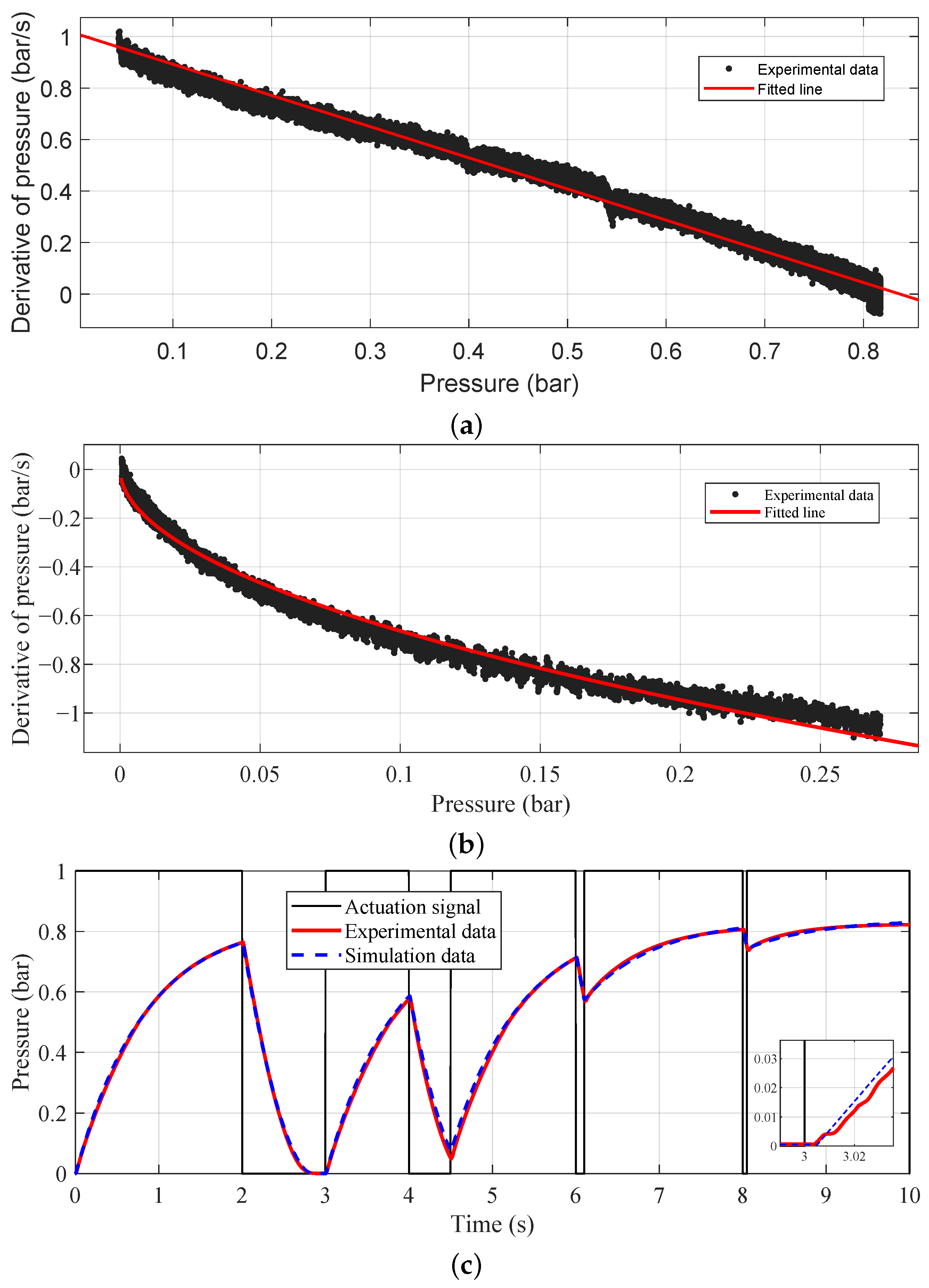

3.2. Identification Results

4. System Behaviour Under Pulse-Type Inputs

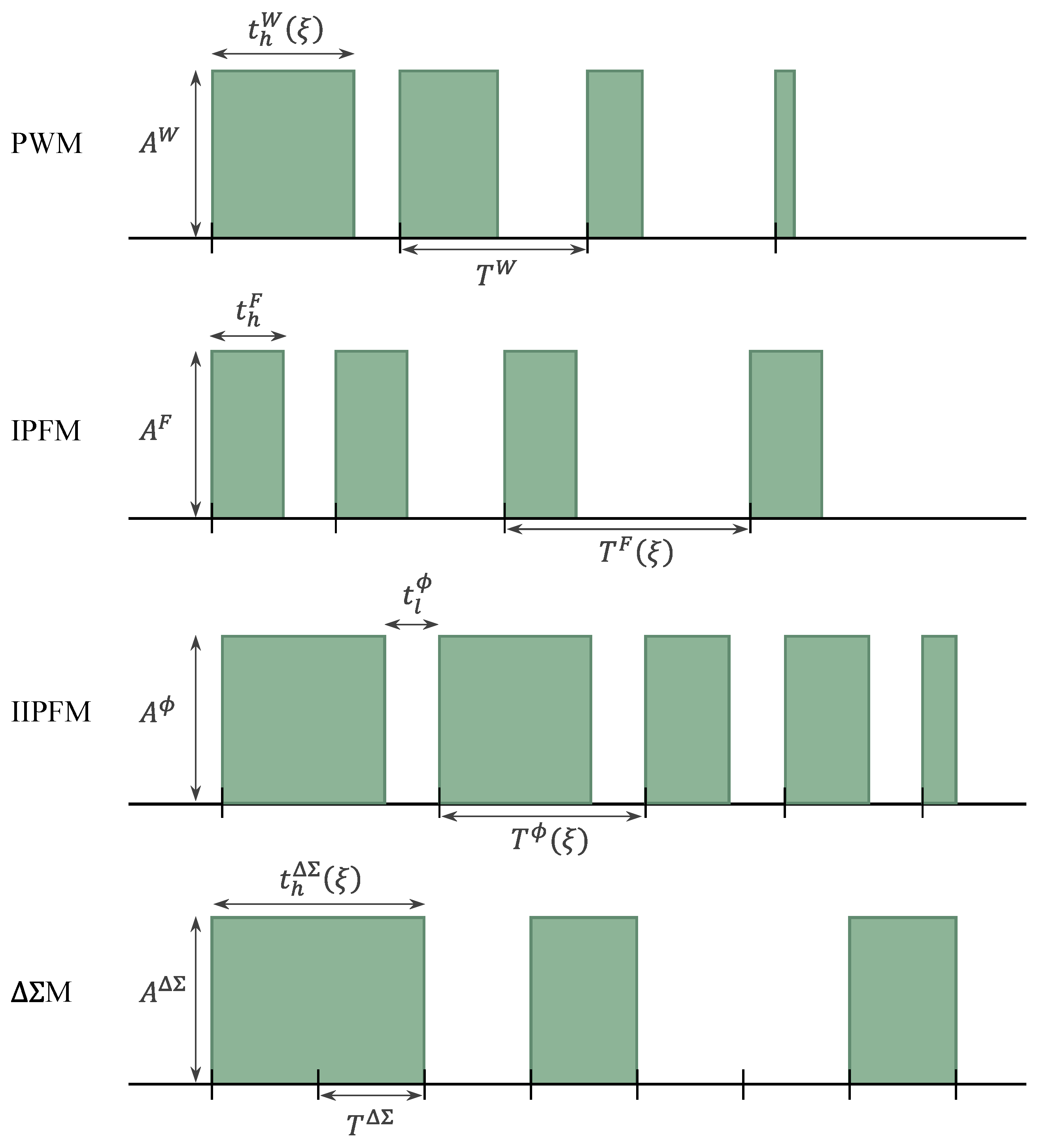

4.1. Fundamentals

4.2. General Analysis

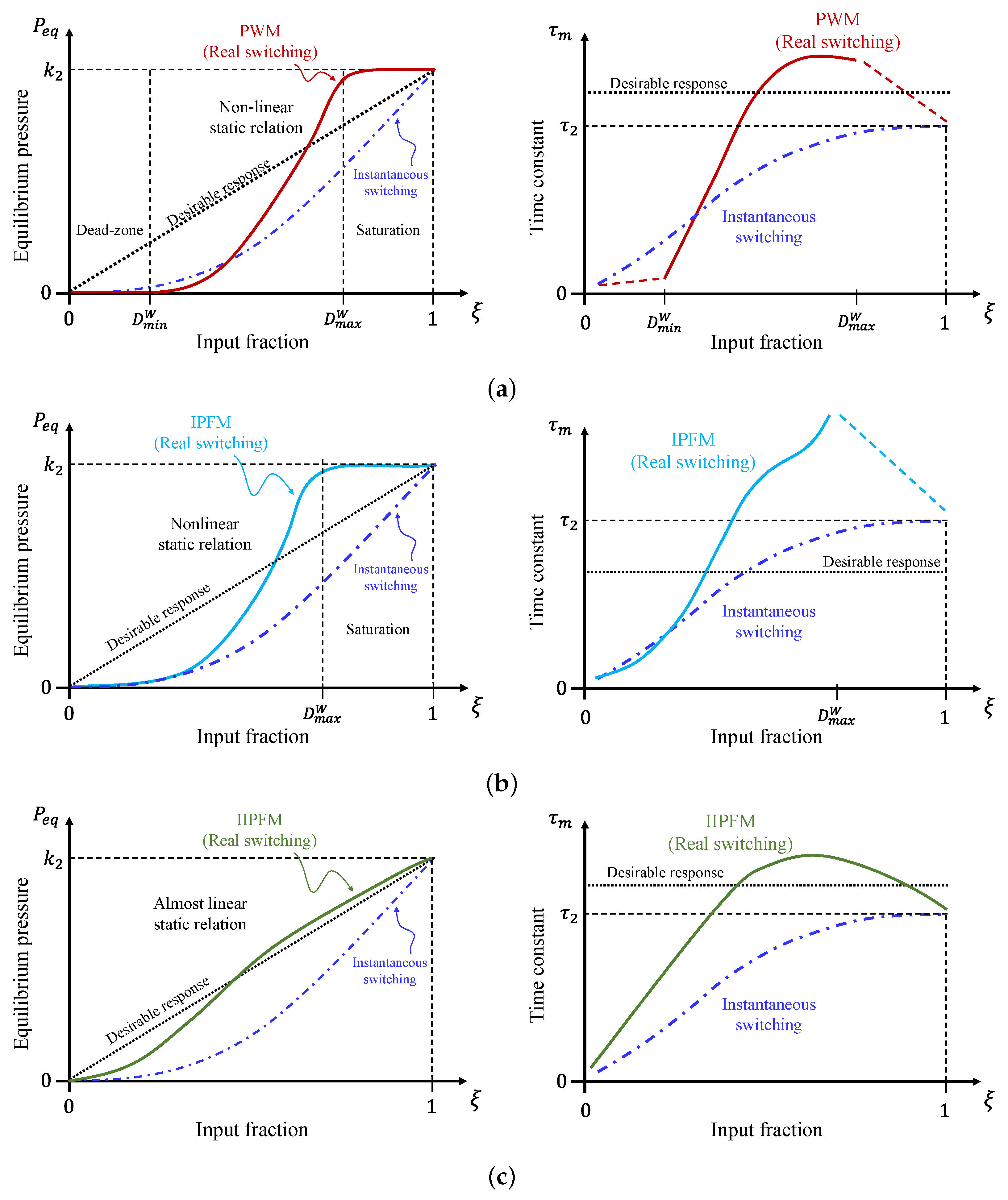

4.2.1. Equilibrium Pressure

4.2.2. Equivalent Dynamics

4.3. Linearity Analysis for Each Modulator

4.3.1. Dead-Zone and Saturation

4.3.2. Static Response

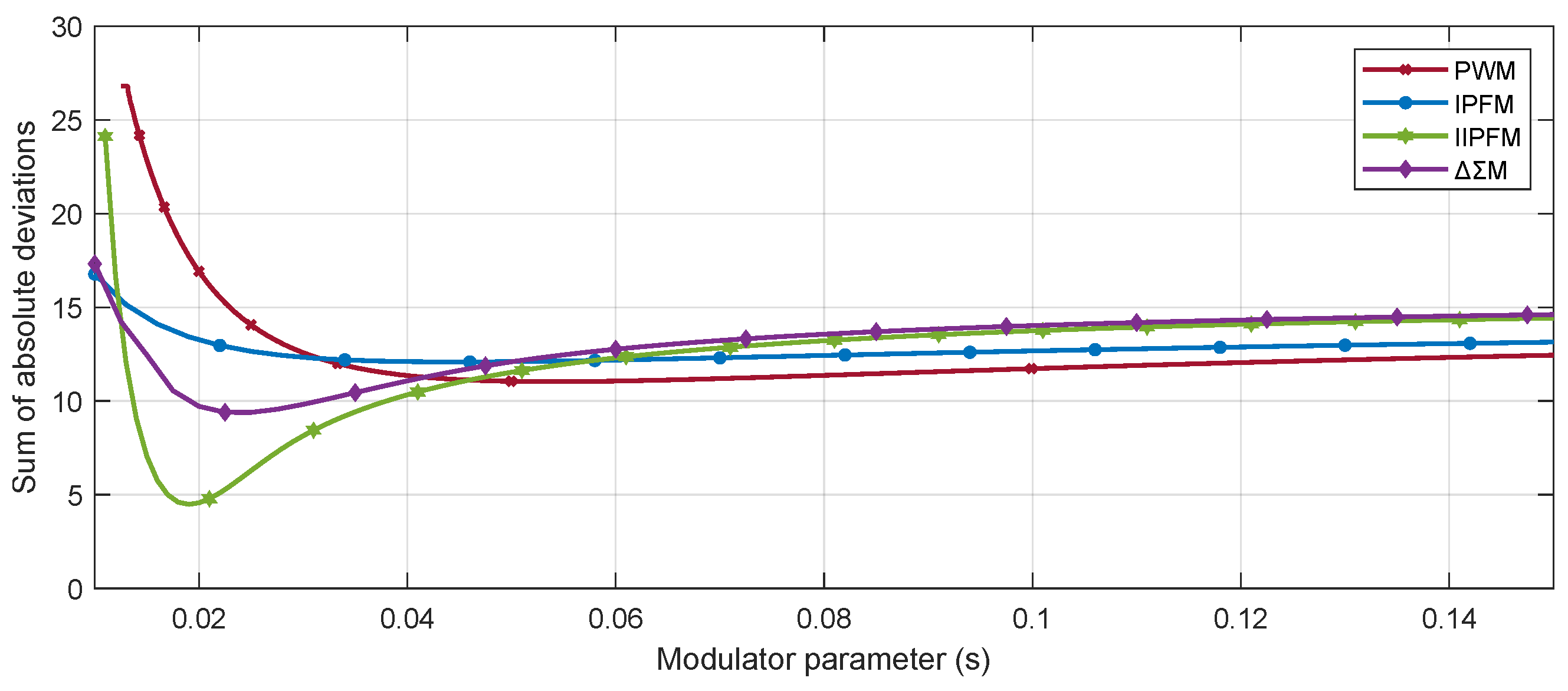

5. Pulse Modulator Tuning by Optimisation

5.1. Tuning Method

5.2. Validation of the Tuning Method

6. Experimental Open-Loop Assessment

6.1. Nonlinearities Dependency on Parameter Tuning

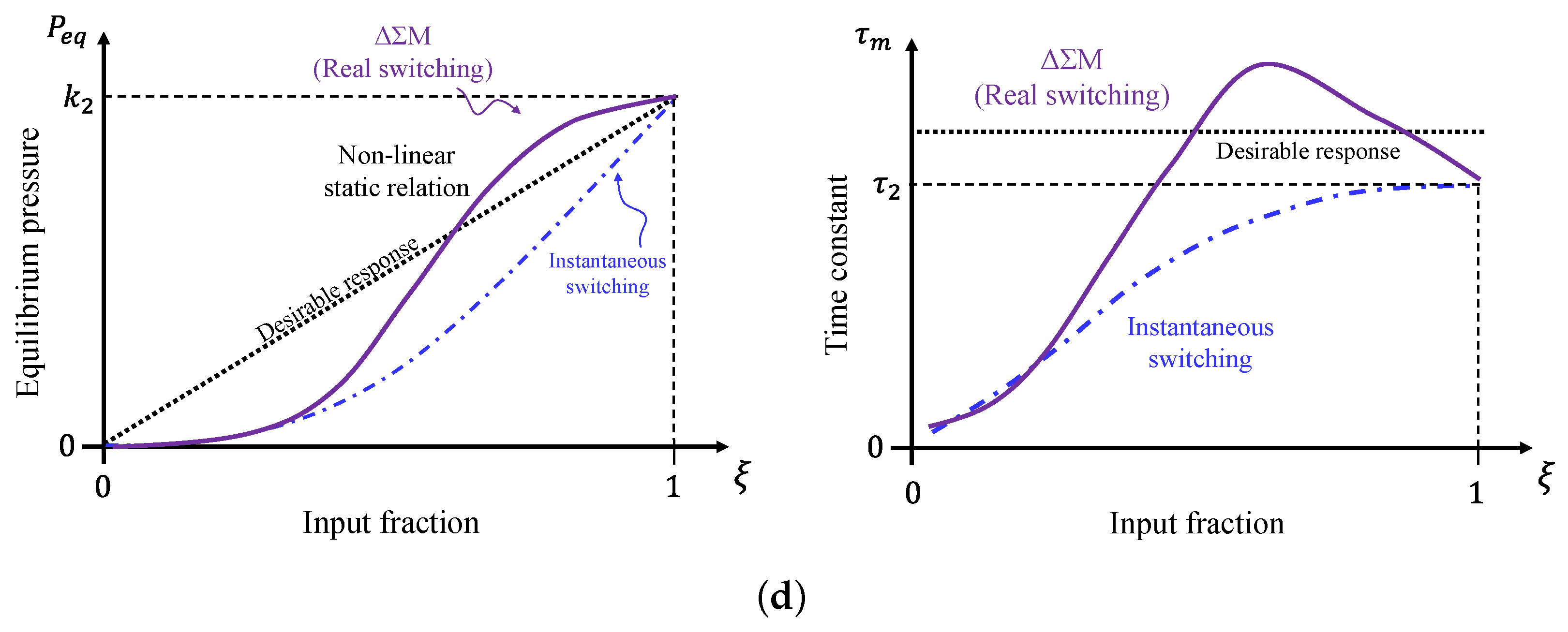

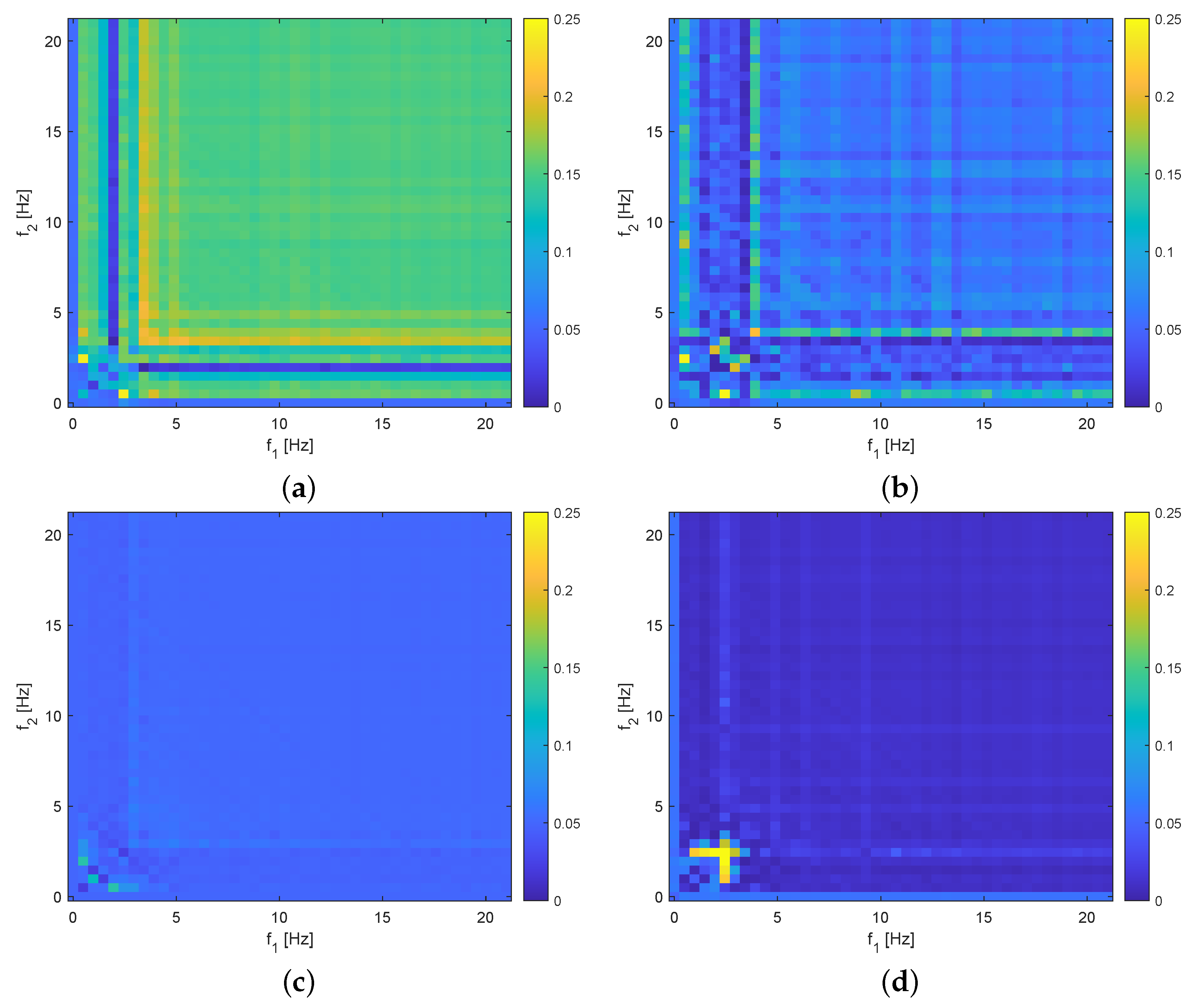

- PWM (Figure 6a): The frequency varied from 1 to 40 Hz. It can be seen that in each case, the steady-state pressure value at each step is not linearly dependent on the input fraction: a change in input fraction from to produces larger changes in output pressure than an increment from to . It is also observed that there is a saturation that increases with frequency, from almost no saturation at Hz to producing saturation at an input fraction of 0.6 at Hz. The dead-zone also increases with frequency, although it is not as relevant as the saturation ( is almost three times smaller than ). Observations agree with reasonings of Section 4.3.1. Finally, chattering increases with decreasing frequency when using PWM and it is greater for intermediate values of input fractions (0.4–0.6). Although at low frequencies the dead-zone and saturation problems are minimised, the measured chattering is very high, which is not suitable for the application as it produces undesired abrupt movements in the actuator. Furthermore, the static response is still nonlinear and the saturation causes the actuator to operate incorrectly close to the tank pressure. The best compromise between reduced chattering and lower saturation is achieved at Hz.

- IPFM (Figure 6b): The pulse width was varied from 5 ms to 100 ms and . As can be seen, there is no dead-zone because the pulse width is greater than the opening time. It is also observed that for small pulse widths (5 and 10 ms) there is an abrupt change in pressure for intermediate input fractions ( and ). The saturation problem is greater than that observed in the PWM case. This is due to the fact that the elapsed time between pulses is reduced as the input increases: . As the pulse width increases, the saturation is reduced but still present () and chattering increases. For a given pulse width, chattering decreases as the input fraction increases because the firing frequency of the pulses increases. In summary, IPFM is good at dealing with the dead-zone, but the nonlinear static response and the saturation problem remain. The case of ms allows the best compromise.

- IIPFM (Figure 6c): The results were obtained for ms and . It is observed that dead-zone and saturation are significant for the smallest pulse width, but for ms the saturation is eliminated. The dead-zone also decreases as the pulse width increases. On the contrary, the chattering increases with pulse width. For a given pulse width, the chattering increases with the input fraction (the opposite to IPFM). The case of ms (the optimal value obtained in Section 5) is of particular interest: the saturation is eliminated, there is an almost linear ratio of proportion between the input fraction and the output pressure (each increment in input fraction produces a similar increment in pressure), and a small dead-zone is observed.

- M (Figure 6d): A first-order M was employed, with the parameter adjusted from 5 ms to 100 ms. As can be observed, this modulator has similar problems to IPFM for the 5 and 10 ms range, but because the high and low state durations of M are multiples of the period, it can be tuned to ensure that both the opening and closing times are met at the same time. With this modulation strategy, both the dead-zone and the saturation are no longer a problem, as seen for ms. However, chattering increases with the period, while its amplitude seems to be almost uniform across all input fractions. The observed pattern in chattering is inconsistent caused by the way in which M is able to encode a given input by using an irregular pattern of equal width pulses. The case corresponding to ms is the most linear case with a low chattering, although it is less linear than the IIPFM for small inputs (0.1–0.4).

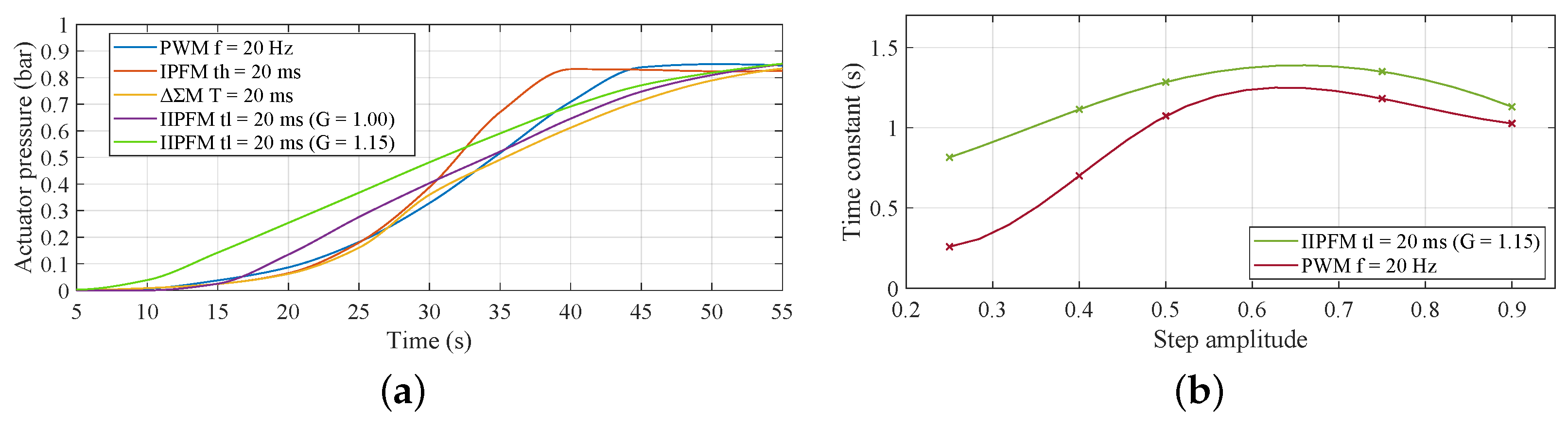

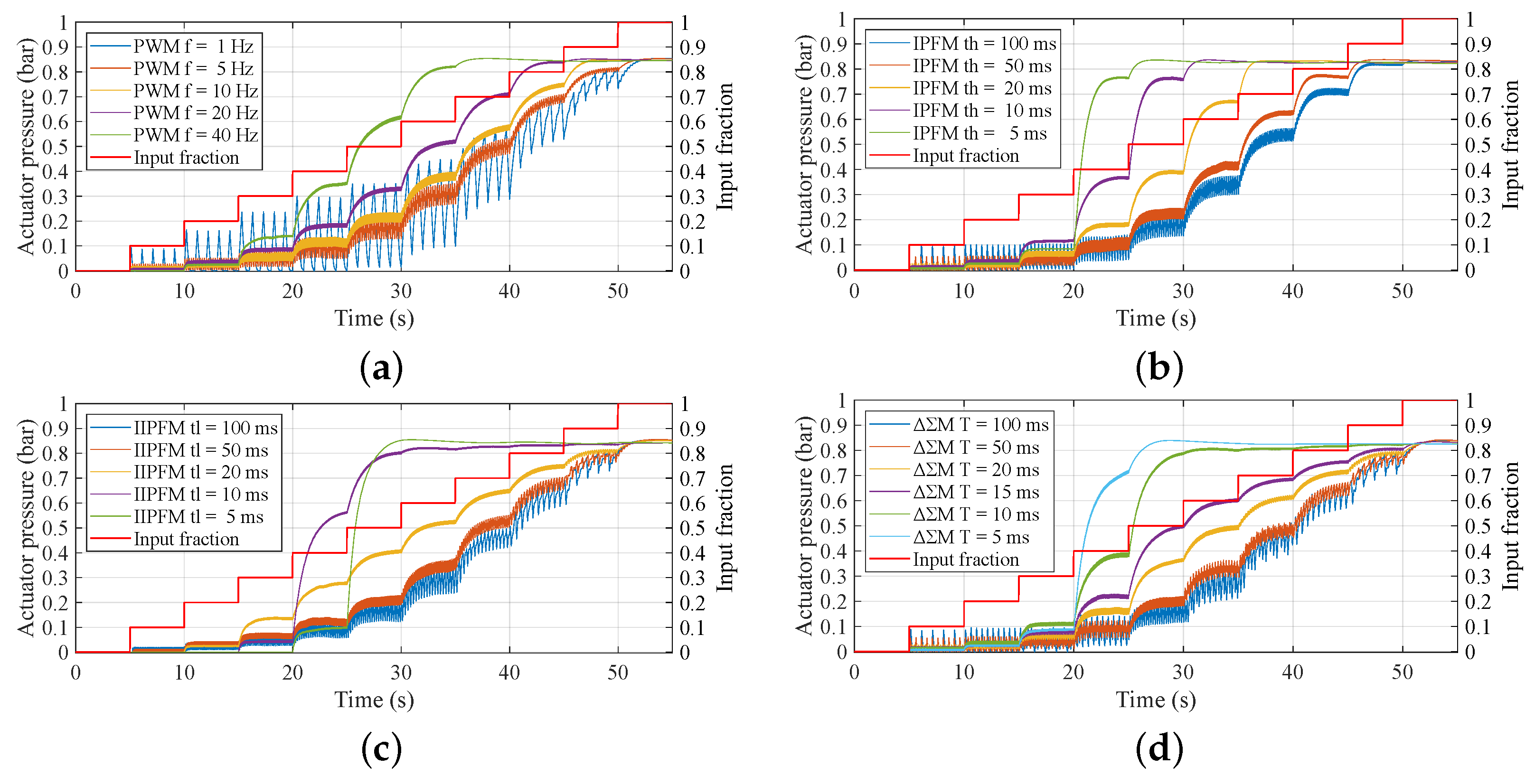

6.2. Static and Dynamic Linearity

- Figure 7a shows the equilibrium pressure is plotted against the input fraction. It can be seen that both PWM and IPFM cause saturation, and the curves are far from being straight lines. In contrast, the IIPFM curves are closer to a straight line. The M is an intermediate case between the IPFM and IIPFM curves. It is also observed that the IIPFM curve with has no dead-zone while preserving the linearity and saturation elimination. To express the linearity of the static curve in a quantitative way, the five experiments were fitted to a line of the form . Table 3 gives the mean square error (MSE), the maximum deviation (MD) and the goodness of fit, in percentage, for all the cases. As can be seen, the best cases in terms of the three performance indices are obtained with the IIPFM. Furthermore, the case further increases the linearity of the system. By contrast, the worst cases in terms of linearity are IPFM and PWM. Note that the MSE is almost 7 times smaller with IIPFM than with PWM, and the fitness has a difference of % in favour of IIPFM.

- Figure 7b shows the measured time constant of the transient response measured when the valve is subjected to input steps against the amplitude of the step for PWM and IIPFM. The time constant of the measurements for IIPFM is s, while s for PWM. The standard deviation of the time constant is almost halved when using IIPFM.

6.3. Frequency Analysis

6.3.1. System Behaviour for Sine Inputs

6.3.2. System Behaviour for Chirp-Type Inputs

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary and Main Findings

7.2. Implications for Control Design and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M | Delta-sigma modulation |

| IPFM | Integral pulse frequency modulation |

| IIPFM | Inverse integral pulse frequency modulation |

| PFM | Pulse frequency modulation |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| SPA | Soft pneumatic actuator |

Appendix A. Fundamental Equations Describing Pulse Trains

| Modulation Type | Firing Frequency | Pulse Width | Low Duration | Duty Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWM | const. | |||

| IPFM | const. | |||

| IIPFM | const. | |||

| M | [*] | [*] |

Appendix B. Actual Pressure Expressions

References

- Hasanshahi, B.; Cao, L.; Song, K.Y.; Zhang, W. Design of Soft Robots: A Review of Methods and Future Opportunities for Research. Machines 2024, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Ul Islam, T.; Islam, M.R. A Review on Recent Trends of Bioinspired Soft Robotics: Actuators, Control Methods, Materials Selection, Sensors, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 7, 2400414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mushtaq, R.T.; Wei, Q. Advancements in Soft Robotics: A Comprehensive Review on Actuation Methods, Materials, and Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasa, O.; Toshimitsu, Y.; Michelis, M.Y.; Jones, L.S.; Filippi, M.; Buchner, T.; Katzschmann, R.K. An Overview of Soft Robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ding, Q.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Huang, J. Programmable Pressure Control in Pneumatic Soft Robots With 2-Way 2-State Solenoid Valves. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6448–6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Tawk, C.D.; Zolfagharian, A.; Pinskier, J.; Howard, D.; Young, T.; Lai, J.; Harrison, S.M.; Yong, Y.K.; Bodaghi, M.; et al. Soft Pneumatic Actuators: A Review of Design, Fabrication, Modeling, Sensing, Control and Applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 59442–59485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, J.; Wu, L.; Fang, B.; Sun, F. Optimal control scheme for pneumatic soft actuator under comparison of proportional and PWM-solenoid valves. Photonic Netw. Commun. 2019, 37, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yin, X.; Peng, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q. Soft pneumatic actuators adapted in multiple environments: A novel fuzzy cascade strategy for the dynamics control with hysteresis compensation. Mechatronics 2022, 84, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnevskis, K.; Kassim, S.O.; Elena Giannaccini, M.; Vaziri, V.; Aphale, S.S. Improved Model of the PWM Driven 3/2 Solenoid Valve Pneumatic System for Soft Pneumatic Actuators. In Proceedings of the 2023 27th International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), Międzyzdroje, Poland, 22–25 August 2023; pp. 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Fleming, A.J.; Yong, Y.K. Nonlinear Estimation and Control of Bending Soft Pneumatic Actuators Using Feedback Linearization and UKF. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 1919–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtara, T.; Nonami, K.; Shao, H.; Yuasa, R.; Amano, S.; Waterman, D.; Nobumoto, Y. Hydraulic master–slave land mine clearance robot hand controlled by pulse modulation. Mechatronics 2005, 15, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, S.; Iwata, T.; Maruyama, Y.; Miki, D. Spiking neural networks-based generation of caterpillar-like soft robot crawling motions. Artif. Life Robot. 2024, 29, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafestas, S.; Frangakis, G. Design and implementation of pulse frequency modulation control systems. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 1980, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Balbontín, A.J.; Tejado, I.; Vinagre, B.M.; Aphale, S.S.; San-Millan, A. Spiking Control of a Solenoid Valve for High-Precision Pressure Regulation in Soft Robotics. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2025; Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- Norsworthy, S.R.; Schreier, R.; Temes, G.C. Delta-Sigma Data Converters: Theory, Design, and Simulation; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aleixandre, M.; Nakazawa, K.; Nakamoto, T. Optimization of Modulation Methods for Solenoid Valves to Realize an Odor Generation System. Sensors 2019, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, T.; Matsumoto, R.; Nakamoto, T. Study of odor blender using solenoid valves controlled by delta–sigma modulation method for odor recorder. Sen. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 87, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, S.O.; Visnevskis, K.; Vaziri, V.; Aphale, S.S. A Dual Cavity Pleated Structures Soft Pneumatic Actuator for Soft Robotic Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE AFRICON, Nairobi, Kenya, 20–22 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Fleming, A.J.; Yong, Y.K. Model-Based Nonlinear Feedback Controllers for Pressure Control of Soft Pneumatic Actuators Using On/Off Valves. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 818187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, N.; Scavarda, S.; Betemps, M.; Jutard, A. Models of a Pneumatic PWM Solenoid Valve for Engineering Applications. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1992, 114, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzern, P.; Spinelli, W. Quadratic stabilization of a switched affine system about a nonequilibrium point. In Proceedings of the 2004 American Control Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 30 June–2 July 2004; Volume 5, pp. 3890–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikias, C.; Mendel, J. Signal processing with higher-order spectra. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 1993, 10, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modulator Type | Dead-Zone | Saturation |

|---|---|---|

| PWM | ||

| IPFM | 0 | |

| IIPFM | 1 | |

| M | 0 | 1 |

| Modulation Type | Restriction | Selected Parameter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWM | Hz | 10.5 | 20 Hz |

| IPFM | ms | 12.5 | 20 ms |

| IIPFM | ms | 4.8 | 20 ms |

| M | ms | 9.6 | 20 ms |

| Modulation Type | MSE () | MD () | FIT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWM | 7.3 | 7.56 | 75.23 |

| IPFM | 13.0 | 10.02 | 68.23 |

| IIPFM () | 2.5 | 4.07 | 84.20 |

| IIPFM () | 1.3 | 3.13 | 87.89 |

| M | 4.5 | 5.55 | 78.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Balbontín, A.J.; Tejado, I.; Vinagre, B.M.; Aphale, S.S.; San-Millan, A. Open-Loop Characterisation of Soft Actuator Pressure Regulated by Pulse-Driven Solenoid Valve. Robotics 2025, 14, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120177

Serrano-Balbontín AJ, Tejado I, Vinagre BM, Aphale SS, San-Millan A. Open-Loop Characterisation of Soft Actuator Pressure Regulated by Pulse-Driven Solenoid Valve. Robotics. 2025; 14(12):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120177

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Balbontín, Andrés J., Inés Tejado, Blas M. Vinagre, Sumeet S. Aphale, and Andres San-Millan. 2025. "Open-Loop Characterisation of Soft Actuator Pressure Regulated by Pulse-Driven Solenoid Valve" Robotics 14, no. 12: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120177

APA StyleSerrano-Balbontín, A. J., Tejado, I., Vinagre, B. M., Aphale, S. S., & San-Millan, A. (2025). Open-Loop Characterisation of Soft Actuator Pressure Regulated by Pulse-Driven Solenoid Valve. Robotics, 14(12), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120177