G2PDeep-v2: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Phenotype Prediction and Biomarker Discovery for All Organisms Using Multi-Omics Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Pre-Processing

2.2. Modeling in G2PDeep

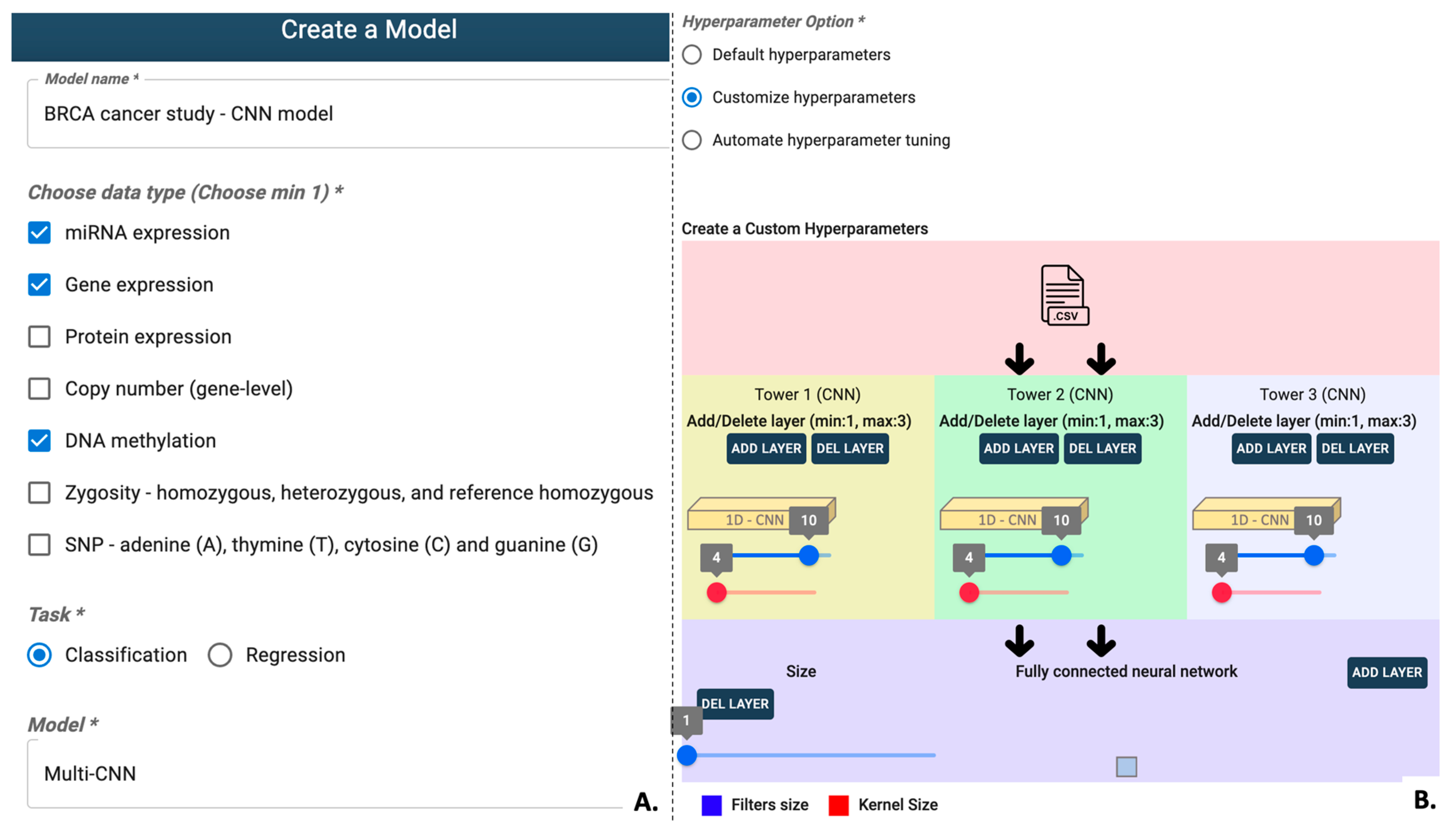

2.2.1. Multi-CNN

2.2.2. Traditional Machine Learning Models

2.3. Biomarkers Discovery and Annotation

2.4. Web Server Implementation

2.4.1. Web Interface Module

2.4.2. Core Backend Module

2.4.3. AI Platform Module

2.4.4. Database Module

2.4.5. Security Policy

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Web Server

3.1.1. Dataset Creation

3.1.2. Model Creation

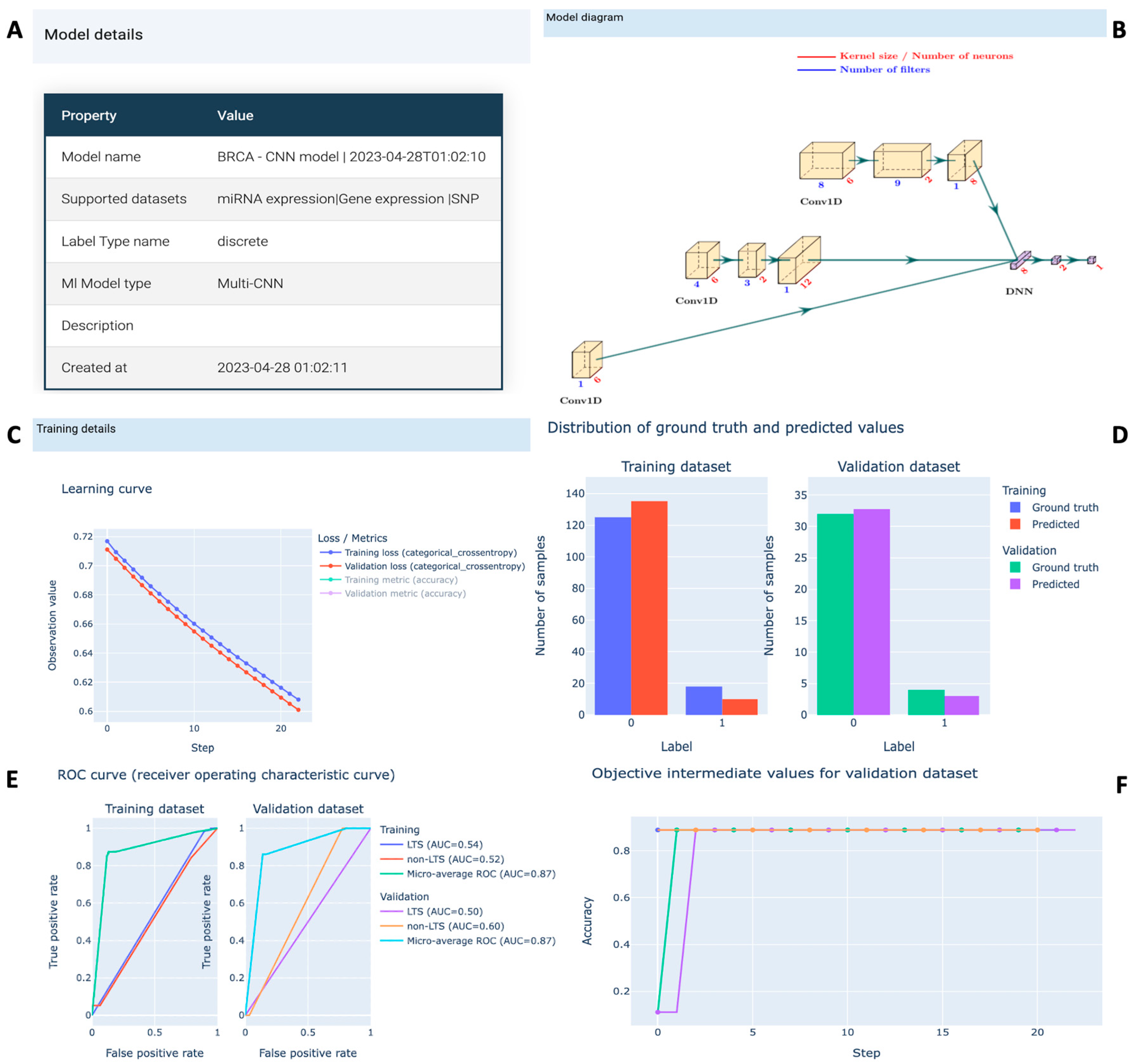

3.1.3. Project for Model Training and Evaluation

3.1.4. Prediction and Significant Biomarkers Discovery

3.1.5. Study Results in G2PDeep-v2

3.2. Application of G2PDeep-v2

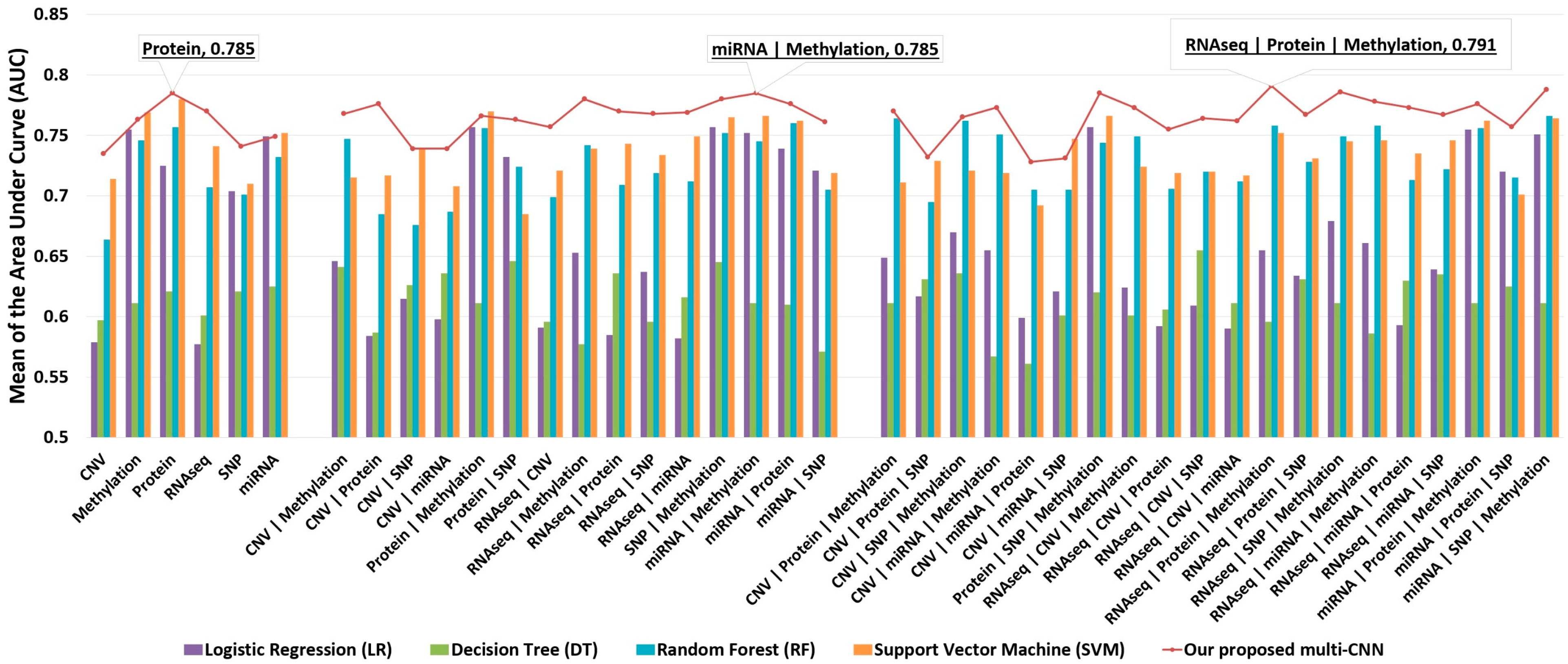

3.2.1. Use Case #1: Long-Term-Survival Prediction and Markers Discovery for Cancer

3.2.2. Use Case #2: Disease Resistance Prediction for Soybean Cyst Nematode (SCN) in Soybean 1066 Lines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | area under the curve |

| BRCA | Breast Invasive Carcinoma |

| CNV | copy number variations |

| CSC | cancer stem cell |

| CSV | comma-separated values |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| HTTP | Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| JWT | JSON Web Token |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LTS | long-term survival |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MVC | Model-View-Controller |

| non-LTS | non-long-term survival |

| PCC | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| RF | Random Forest |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SKCM | Skin Cutaneous Melanoma |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| UI | user interface |

References

- Menyhárt, O.; Győrffy, B. Multi-Omics Approaches in Cancer Research with Applications in Tumor Subtyping, Prognosis, and Diagnosis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-Omics Approaches to Disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, K.S.; Lozada, D.N.; Zhang, Z.; Pumphrey, M.O.; Carter, A.H. Deep Learning for Predicting Complex Traits in Spring Wheat Breeding Program. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 613325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulos, C.; Hindupur, S.K.; Colombi, M.; Liko, D.; Ng, C.K.; Piscuoglio, S.; Behr, J.; Moore, A.L.; Singer, J.; Ruscheweyh, H.J. Multi-Omics Data Integration Reveals Novel Drug Targets in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lye, X.; Kaalia, R.; Kumar, P.; Rajapakse, J.C. Deep Learning and Multi-Omics Approach to Predict Drug Responses in Cancer. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, I.R.; Aswad, L.; Stahl, M.; Kunold, E.; Post, F.; Erkers, T.; Struyf, N.; Mermelekas, G.; Joshi, R.N.; Gracia-Villacampa, E. Integrative Multi-Omics and Drug Response Profiling of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Lines. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Qiu, Z.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Cheng, Q.; Zhai, J.; Ma, C. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach for Predicting Phenotypes from Genotypes. Planta 2018, 248, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanczar, B.; Zehraoui, F.; Issa, T.; Arles, M. Biological Interpretation of Deep Neural Network for Phenotype Prediction Based on Gene Expression. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shao, W.; Huang, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Huang, K. MOGONET Integrates Multi-Omics Data Using Graph Convolutional Networks Allowing Patient Classification and Biomarker Identification. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammut, S.-J.; Crispin-Ortuzar, M.; Chin, S.-F.; Provenzano, E.; Bardwell, H.A.; Ma, W.; Cope, W.; Dariush, A.; Dawson, S.-J.; Abraham, J.E.; et al. Multi-Omic Machine Learning Predictor of Breast Cancer Therapy Response. Nature 2022, 601, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmarakeby, H.A.; Hwang, J.; Arafeh, R.; Crowdis, J.; Gang, S.; Liu, D.; AlDubayan, S.H.; Salari, K.; Kregel, S.; Richter, C.; et al. Biologically Informed Deep Neural Network for Prostate Cancer Discovery. Nature 2021, 598, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Choi, W.; Ko, E.; Kang, M.; Tannenbaum, A.; Deasy, J.O. PathCNN: Interpretable Convolutional Neural Networks for Survival Prediction and Pathway Analysis Applied to Glioblastoma. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, i443–i450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirion, O.B.; Jing, Z.; Chaudhary, K.; Huang, S.; Garmire, L.X. DeepProg: An Ensemble of Deep-Learning and Machine-Learning Models for Prognosis Prediction Using Multi-Omics Data. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; He, F.; Wang, J.; Joshi, T.; Xu, D. Phenotype Prediction and Genome-Wide Association Study Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network of Soybean. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Mao, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, D.; Joshi, T. G2PDeep: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Quantitative Phenotype Prediction and Discovery of Genomic Markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W228–W236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: New Perspectives on Genomes, Pathways, Diseases and Drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; Viteri, G.; Gong, C.; Lorente, P.; Fabregat, A.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Cook, J.; Gillespie, M.; Haw, R. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D498–D503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Portal 2022; National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, A.L.; Hannun, A.Y.; Ng, A.Y. Rectifier Nonlinearities Improve Neural Network Acoustic Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2013, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; Volume 30, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, X.; Peltz, G. GSEApy: A Comprehensive Package for Performing Gene Set Enrichment Analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facebook React; Meta Platforms: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2022.

- Google Material-UI; Google LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023.

- Plotly Technologies Inc. P.T. Collaborative Data Science. Available online: https://plot.ly (accessed on 1 January 2012).

- Django Software Foundation. Django; Django Software Foundation: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celery Team. Celery. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/celery/celery (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, S.G.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1603.04467. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Keras. 2015. Available online: https://keras.io/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Oracle Corporation. MySQL; Oracle Corporation: Austin, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo, S. Redis Labs. Redis; Redis Labs: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- JWT Team. JSON Web Token; Auth0: Bellevue, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, S.A.; Vaughn, M.; McKay, S.; Lyons, E.; Stapleton, A.E.; Gessler, D.; Matasci, N.; Wang, L.; Hanlon, M.; Lenards, A. The iPlant Collaborative: Cyberinfrastructure for Plant Biology. Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, N.; Lyons, E.; Goff, S.; Vaughn, M.; Ware, D.; Micklos, D.; Antin, P. The iPlant Collaborative: Cyberinfrastructure for Enabling Data to Discovery for the Life Sciences. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Yan, L.; Quigley, C.; Jordan, B.D.; Fickus, E.; Schroeder, S.; Song, B.H.; Charles An, Y.Q.; Hyten, D.; Nelson, R. Genetic Characterization of the Soybean Nested Association Mapping Population. Plant Genome 2017, 10, plantgenome2016-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandillo, N.; Jarquin, D.; Song, Q.; Nelson, R.; Cregan, P.; Specht, J.; Lorenz, A. A Population Structure and Genome-wide Association Analysis on the USDA Soybean Germplasm Collection. Plant Genome 2015, 8, plantgenome2015-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 4, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar]

- FireBrowse Team. FireBrowse. 2016. Available online: http://firebrowse.org/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Dietz, K.; Gail, M.; Klein, M.; Klein, M. Logistic Regression; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; ISBN 0-387-95397-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hearst, M.A.; Dumais, S.T.; Osuna, E.; Platt, J.; Scholkopf, B. Support Vector Machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 1998, 13, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Y.; Ying, L.U. Decision Tree Methods: Applications for Classification and Prediction. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A Random Forest Guided Tour. Test 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Phillips, S.; Kundra, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, J.E.; Yaeger, R.; Soumerai, T.; Nissan, M.H. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.W.; Rexer, B.N.; Garrett, J.T.; Arteaga, C.L. Mutations in the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Pathway: Role in Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Implications in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ščupáková, K.; Adelaja, O.T.; Balluff, B.; Ayyappan, V.; Tressler, C.M.; Jenkinson, N.M.; Claes, B.S.; Bowman, A.P.; Cimino-Mathews, A.M.; White, M.J. Clinical Importance of High-Mannose, Fucosylated, and Complex N-Glycans in Breast Cancer Metastasis. Jci Insight 2021, 6, e146945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnie, G.; Clarke, R.B.; Spence, K.; Pinnock, N.; Brennan, K.; Anderson, N.G.; Bundred, N.J. Novel Cell Culture Technique for Primary Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: Role of Notch and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Pathways. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Zeng, S.; Xu, B.; Xu, D. The Evolution of Soybean Knowledge Base (SoyKB). In Plant Genomics Databases: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Q.; Lin, B.; Guo, B.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Liao, J.; Zhuo, K. CRISPR/Cas9-Targeted Mutagenesis of a Representative Member of a Novel PR10/Bet v1-like Protein Subfamily Significantly Reduces Rice Plant Height and Defense against Meloidogyne Graminicola. Phytopathol. Res. 2022, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.O.; Biová, J.; Mahmood, A.; Dietz, N.; Bilyeu, K.; Škrabišová, M.; Joshi, T. Genomic Variations Explorer (GenVarX): A Toolset for Annotating Promoter and CNV Regions Using Genotypic and Phenotypic Differences. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1251382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Patil, K.; Fitzpatrick, M.R.; Franklin, L.D.; Yao, Q.; Cook, J.R.; Wang, Z.; Libault, M.; Brechenmacher, L.; Valliyodan, B. Soybean Knowledge Base (SoyKB): A Web Resource for Soybean Translational Genomics. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Škrabišová, M.; Lyu, Z.; Chan, Y.O.; Dietz, N.; Bilyeu, K.; Joshi, T. Application of SNPViz v2.0 Using next-Generation Sequencing Data Sets in the Discovery of Potential Causative Mutations in Candidate Genes Associated with Phenotypes. Int. J. Data Min. Bioinform. 2021, 25, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Škrabišová, M.; Lyu, Z.; Chan, Y.O.; Bilyeu, K.; Joshi, T. SNPViz v2.0: A Web-Based Tool for Enhanced Haplotype Analysis Using Large Scale Resequencing Datasets and Discovery of Phenotypes Causative Gene Using Allelic Variations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–19 December 2020; pp. 1408–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Langewisch, T.; Zhang, H.; Vincent, R.; Joshi, T.; Xu, D.; Bilyeu, K. Major Soybean Maturity Gene Haplotypes Revealed by SNPViz Analysis of 72 Sequenced Soybean Genomes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94150. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0094150 (accessed on 14 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimand, J.; Kull, M.; Peterson, H.; Hansen, J.; Vilo, J. G:Profiler—A Web-Based Toolset for Functional Profiling of Gene Lists from Large-Scale Experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W193–W200. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/35/suppl_2/W193/2920757 (accessed on 14 November 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Zhou, F.; Ren, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, S. A Selective Review of Multi-Level Omics Data Integration Using Variable Selection. High Throughput 2019, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories | Functionality | G2PDeep-v1 | G2PDeep-v2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset creation | single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP)/Zygosity | ✔ | ✔ |

| gene expression | ✔ | ||

| copy number variation (CNV) | ✔ | ||

| Protein expression | ✔ | ||

| microRNA (miRNA) expression | ✔ | ||

| DNA Methylation | ✔ | ||

| Custom models | dual-CNN/multi-CNN | ✔ | ✔ |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | ✔ | ||

| Logistic Regression (LR) | ✔ | ||

| Random Forest (RF) | ✔ | ||

| Decision Tree (DT) | ✔ | ||

| Multiple inputs | ✔ | ||

| Task | Regression | ✔ | ✔ |

| Classification | ✔ | ||

| Model training | Online training | ✔ | ✔ |

| Training monitoring | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Automate hyperparameter tunning | ✔ | ||

| Hyperparameter tunning monitoring | ✔ | ||

| Online prediction | Prediction with test dataset | ✔ | ✔ |

| Marker discovery | Identifying significant markers | ✔ | ✔ |

| GSEA with KEGG/Reactome | ✔ | ||

| Studies related to significant markers | ✔ |

| Study | Number of Samples (LTS/Non-LTS) | Number of Features | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | miRNA Expression | DNA Methylation | Protein Expression | SNP | CNV | ||

| BLCA | 42 (15/27) | 20,533 | 1048 | 300,869 | 225 | 18,634 | 24,778 |

| HNSC | 39 (14/25) | 20,533 | 1048 | 300,973 | 239 | 17,796 | 24,778 |

| LUAD | 33 (16/17) | 20,533 | 1048 | 300,822 | 239 | 18,950 | 24,778 |

| LUSC | 28 (15/13) | 20,533 | 1048 | 300,970 | 239 | 18,822 | 24,778 |

| SARC | 26 (15/11) | 20,533 | 1048 | 299,776 | 219 | 12,422 | 24,778 |

| SKCM | 41 (29/12) | 20,533 | 1048 | 300,455 | 225 | 19,488 | 24,778 |

| Study | Number of Samples (LTS/Non-LTS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | miRNA Expression | DNA Methylation | Protein Expression | SNP | |

| ACC | 62 (44/18) | 63 (44/19) | 63 (44/19) | 36 (28/8) | 73 (50/23) |

| BLCA | 248 (87/161) | 250 (89/161) | 252 (89/163) | 215 (76/139) | 252 (89/163) |

| BRCA | 506 (437/69) | 344 (296/48) | 364 (314/50) | 410 (351/59) | 455 (395/60) |

| CESC | 146 (91/55) | 146 (91/55) | 146 (91/55) | 65 (44/21) | 138 (86/52) |

| CHOL | 26 (11/15) | 26 (11/15) | 26 (11/15) | 22 (9/13) | 26 (11/15) |

| COAD | 126 (78/48) | 91 (56/35) | 130 (81/49) | 133 (79/54) | 172 (101/71) |

| ESCA | 86 (17/69) | 87 (18/69) | 87 (18/69) | 51 (12/39) | 86 (18/68) |

| HNSC | 327 (144/183) | 298 (128/170) | 331 (145/186) | 230 (89/141) | 318 (135/183) |

| KICH | 53 (47/6) | 53 (47/6) | 53 (47/6) | 51 (45/6) | 53 (47/6) |

| KIRC | 404 (293/111) | 177 (132/45) | 228 (157/71) | 246 (173/73) | 226 (173/53) |

| KIRP | 127 (100/27) | 127 (100/27) | 120 (94/26) | 95 (75/20) | 120 (94/26) |

| LIHC | 195 (91/104) | 195 (92/103) | 199 (94/105) | 109 (35/74) | 189 (89/100) |

| LUAD | 270 (133/137) | 223 (109/114) | 230 (112/118) | 204 (102/102) | 269 (133/136) |

| LUSC | 305 (149/156) | 196 (95/101) | 222 (111/111) | 204 (106/98) | 302 (146/156) |

| MESO | 80 (14/66) | 80 (14/66) | 80 (14/66) | 58 (8/50) | 76 (14/62) |

| PAAD | 108 (20/88) | 108 (20/88) | 114 (21/93) | 70 (11/59) | 112 (21/91) |

| READ | 38 (27/11) | 33 (23/10) | 40 (29/11) | 46 (30/16) | 49 (36/13) |

| SARC | 177 (108/69) | 177 (108/69) | 179 (109/70) | 150 (87/63) | 159 (96/63) |

| SKCM | 335 (227/108) | 322 (219/103) | 336 (227/109) | 236 (152/84) | 334 (226/108) |

| STAD | 196 (48/148) | 184 (47/137) | 189 (49/140) | 170 (38/132) | 208 (49/159) |

| THCA | 208 (199/9) | 209 (200/9) | 210 (201/9) | 169 (160/9) | 205 (198/7) |

| UCEC | 69 (44/25) | 183 (127/56) | 193 (137/56) | 217 (163/54) | 273 (208/65) |

| UCS | 42 (12/30) | 41 (12/29) | 42 (12/30) | 36 (8/28) | 42 (12/30) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, S.; Adusumilli, T.; Awan, S.Z.; Immadi, M.S.; Xu, D.; Joshi, T. G2PDeep-v2: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Phenotype Prediction and Biomarker Discovery for All Organisms Using Multi-Omics Data. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121673

Zeng S, Adusumilli T, Awan SZ, Immadi MS, Xu D, Joshi T. G2PDeep-v2: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Phenotype Prediction and Biomarker Discovery for All Organisms Using Multi-Omics Data. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121673

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Shuai, Trinath Adusumilli, Sania Zafar Awan, Manish Sridhar Immadi, Dong Xu, and Trupti Joshi. 2025. "G2PDeep-v2: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Phenotype Prediction and Biomarker Discovery for All Organisms Using Multi-Omics Data" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121673

APA StyleZeng, S., Adusumilli, T., Awan, S. Z., Immadi, M. S., Xu, D., & Joshi, T. (2025). G2PDeep-v2: A Web-Based Deep-Learning Framework for Phenotype Prediction and Biomarker Discovery for All Organisms Using Multi-Omics Data. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121673