Taurine Attenuates M1 Macrophage Polarization and IL-1β Production by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Pathway via Metabolic Reprogramming

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies

2.2. Isolation of Thioglycolate-Elicited Peritoneal Macrophages (TGPMs)

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.4. Quantitative PCR Analysis

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.6. Immunoblot

2.7. Metabolites Analysis

2.8. Animal Experiment

2.9. Histological Analysis

2.10. Immunohistochemistry

2.11. Immunostaining

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Taurine Inhibits M1 Macrophage Inflammation

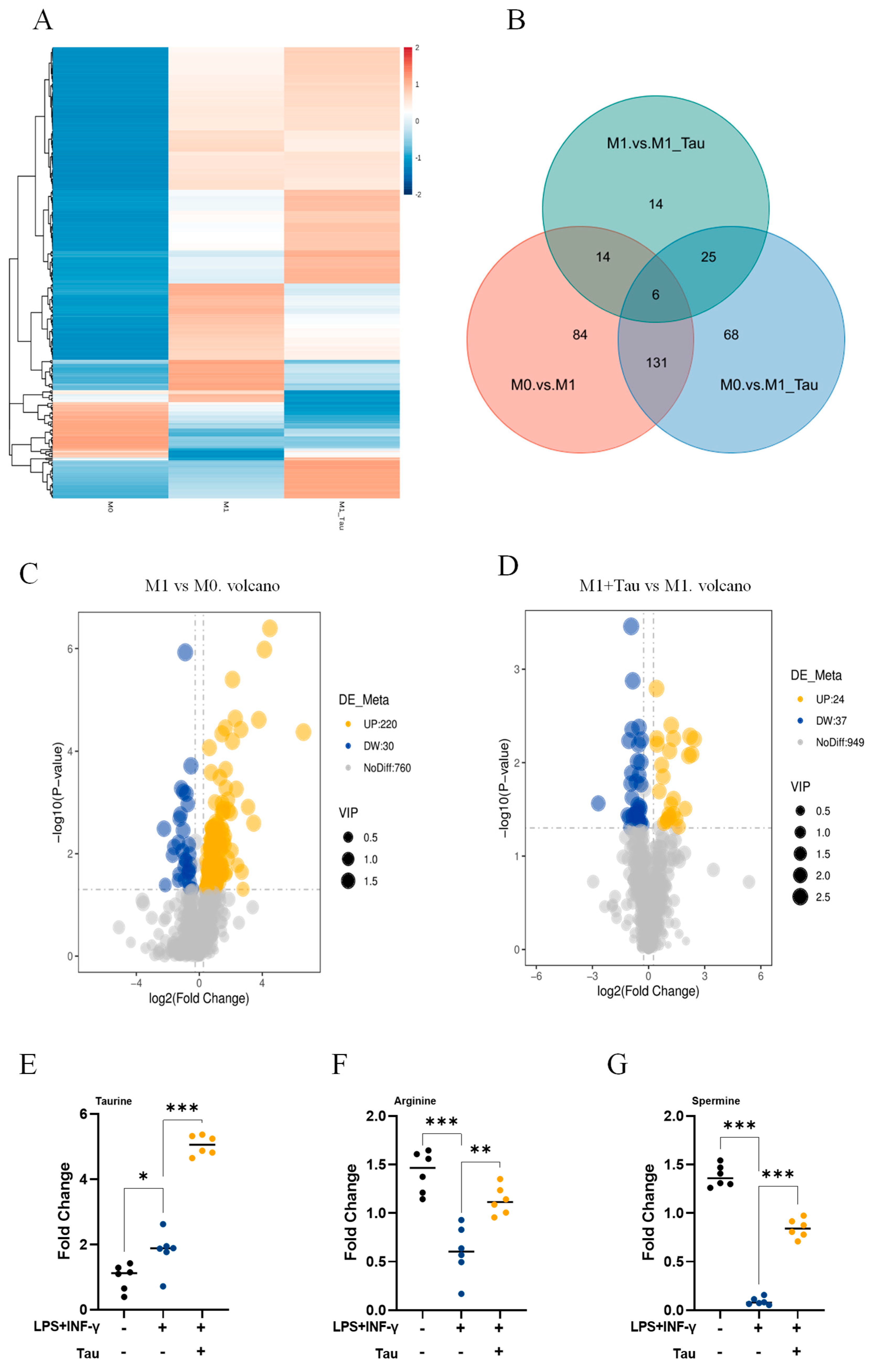

3.2. Taurine Induces Metabolic Reprogramming in M1 Macrophages

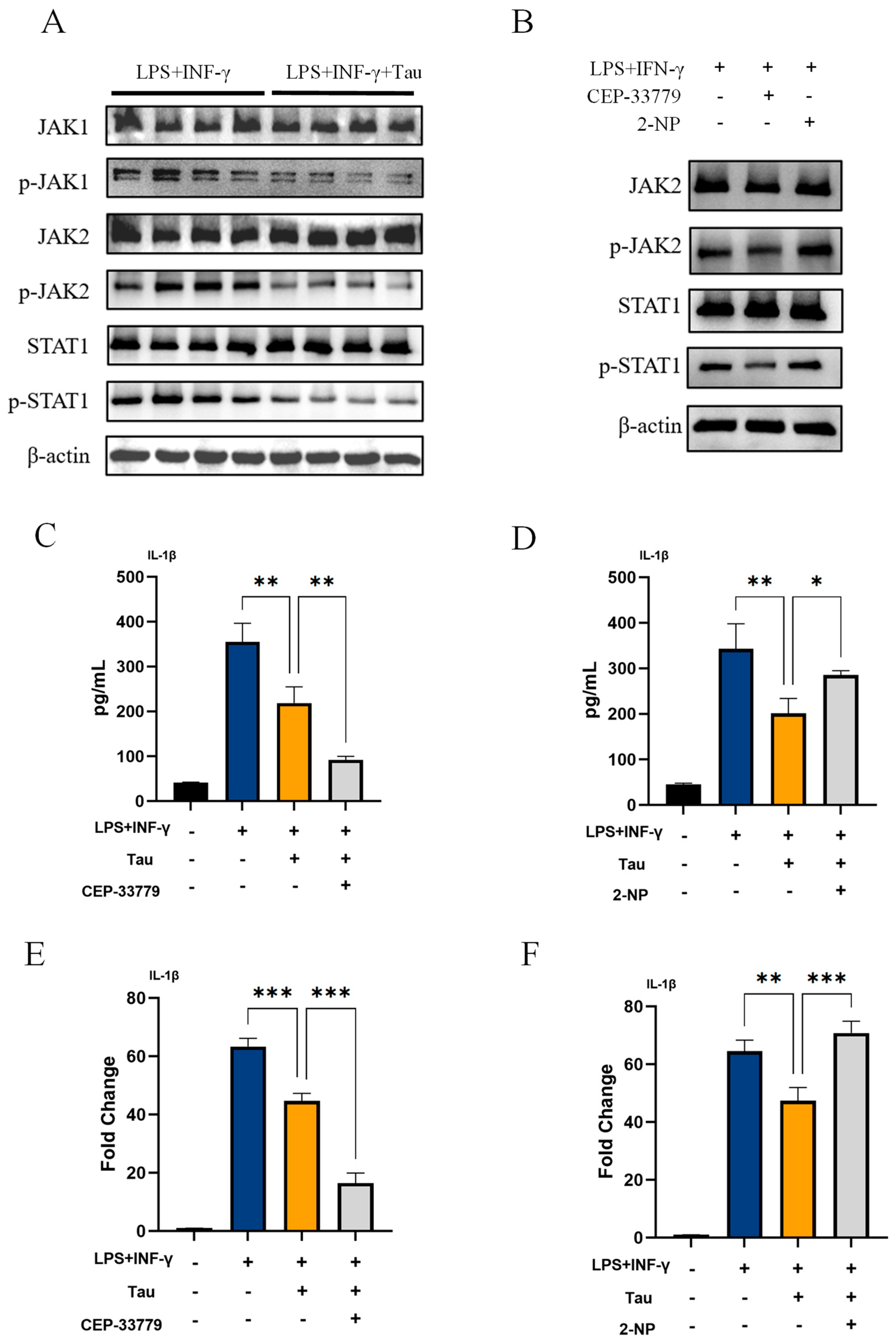

3.3. Taurine Inhibits IL-1β Production in M1 Macrophages by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Signaling Pathway

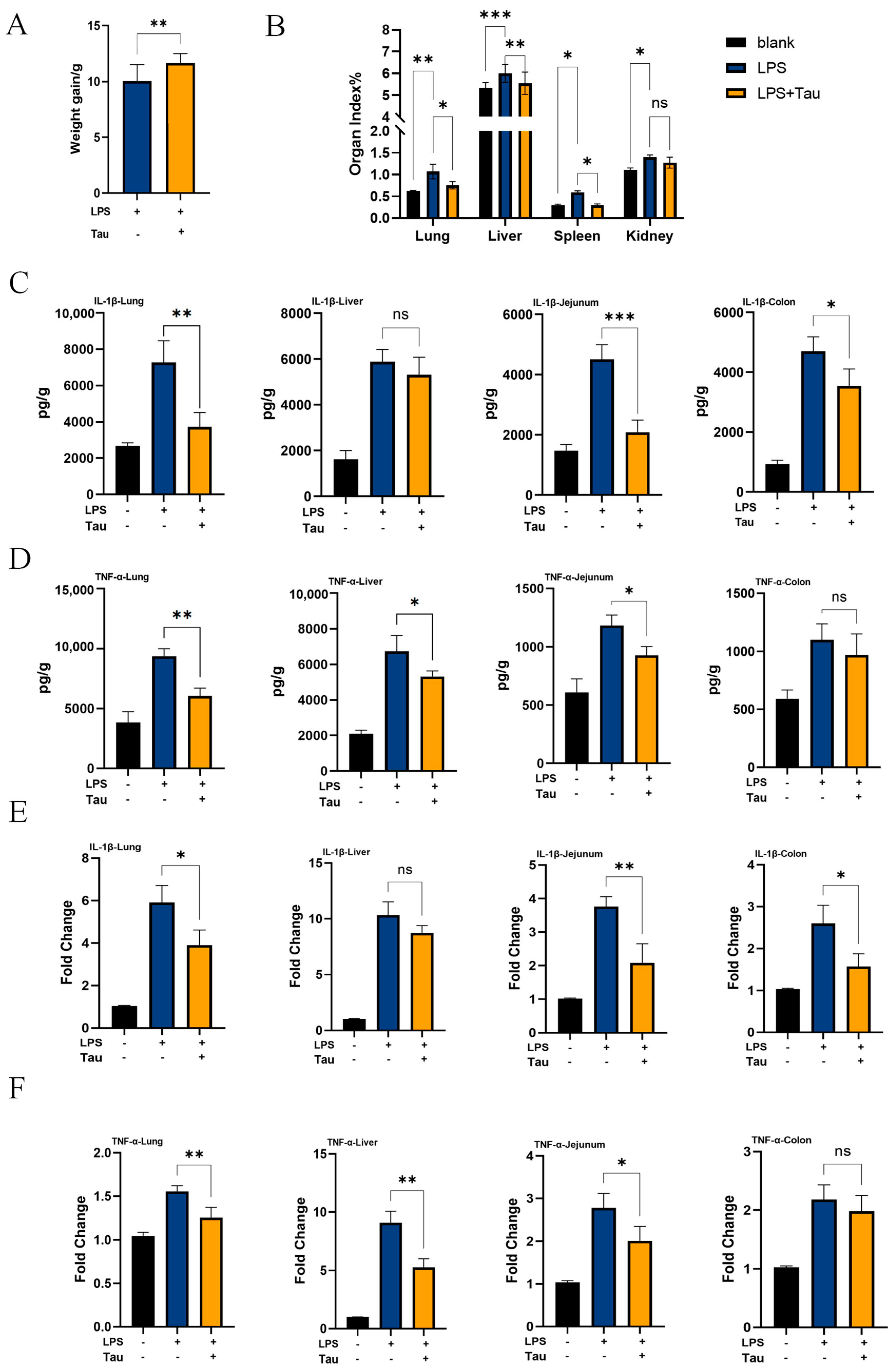

3.4. Taurine Alleviates Systemic Inflammation In Vivo

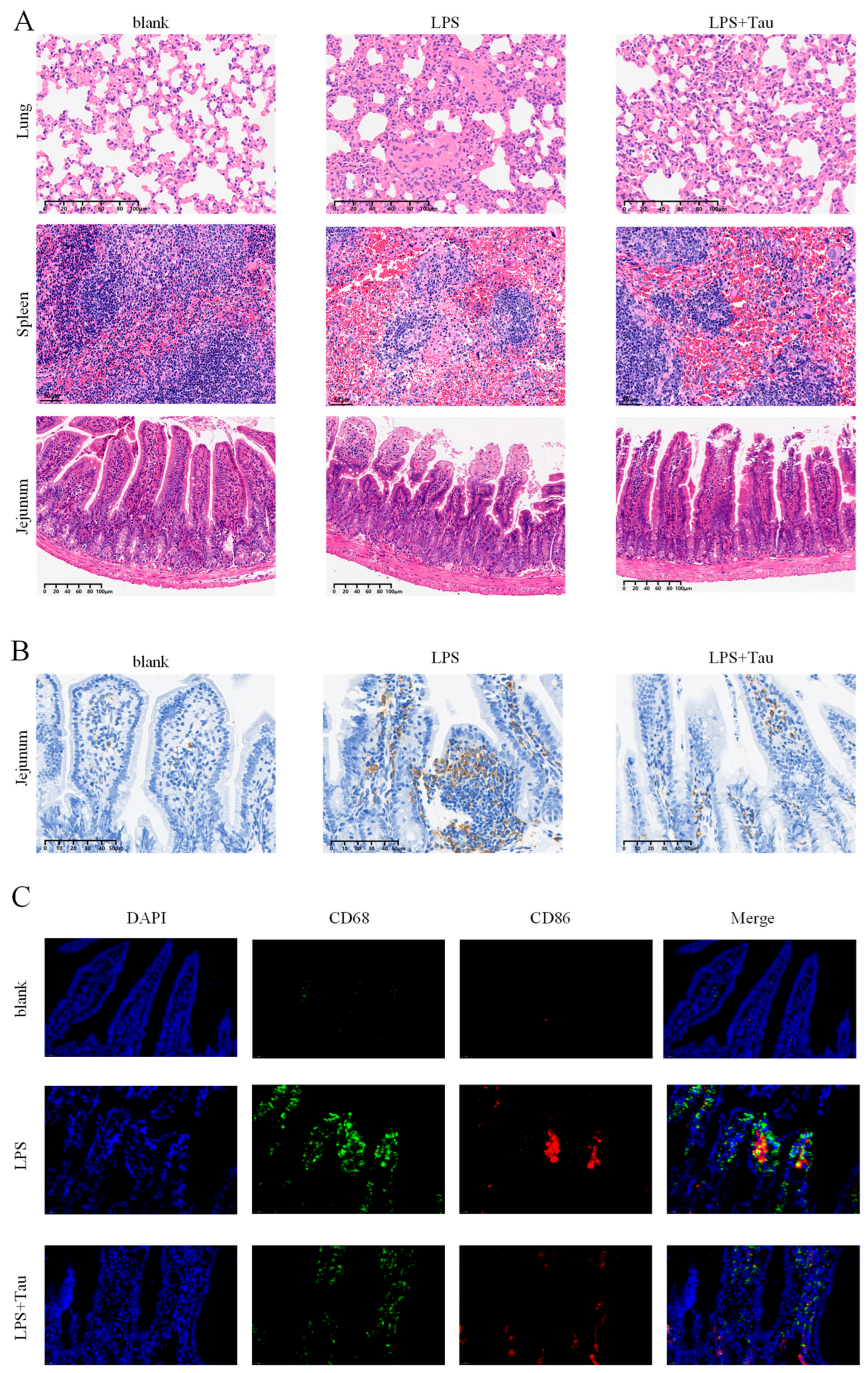

3.5. Taurine Alleviates Histopathological Damage and Intestinal Macrophage Polarization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Locati, M.; Curtale, G.; Mantovani, A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Corr, E.M.; Erbay, E.; Moore, K.J. Regulation of macrophage immunometabolism in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J. Macrophage Polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginhoux, F.; Schultze, J.L.; Murray, P.J.; Ochando, J.; Biswas, S.K. New insights into the multidimensional concept of macrophage ontogeny, activation and function. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasch, S.; Giansanti, P.; Kolter, J.; Riedl, A.; Forde, A.J.; Runge, S.; Zenke, S.; Elling, R.; Halenius, A.; Brabletz, S.; et al. Cytomegalovirus subverts macrophage identity. Cell 2021, 184, 3774–3793.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, X.; Wei, S.; Jiang, P.; Xue, L.; Wang, J. Tumor-associated macrophages: Potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects in cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Targeting macrophage immunometabolism: Dawn in the darkness of sepsis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 58, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.V.; Markin, A.M.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. The Role of Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, S. The physiological and pathophysiological roles of taurine in adipose tissue in relation to obesity. Life Sci. 2017, 186, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, M.W.; Ko, J.I.; Doh, H.M.; Kim, W.B.; Park, T.S.; Shim, M.J.; Kim, B.K. Protective effect of taurine on TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1998, 21, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Cha, Y.N. Taurine chloramine produced from taurine under inflammation provides anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Kishton, R.J.; Rathmell, J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Pearce, E.L. Amino Assets: How Amino Acids Support Immunity. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, M.; Müller, I.; Kropf, P.; Closs, E.I.; Munder, M. Metabolism via Arginase or Nitric Oxide Synthase: Two Competing Arginine Pathways in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, S.M.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.; Siddiqi, F.; Lee, J.E.; Menzies, F.M.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Leucine Signals to mTORC1 via Its Metabolite Acetyl-Coenzyme A. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 192–201.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, D.; Yao, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, X.; Xia, W.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Lu, Y. Glutamine and cancer: Metabolism, immune microenvironment, and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun. Signal 2025, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Chen, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, E.Y.; Hong, S.T.; Park, B.H.; Park, J.H. mTOR- and SGK-Mediated Connexin 43 Expression Participates in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophage Migration through the iNOS/Src/FAK Axis. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 2986–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Allen, J.E.; Biswas, S.K.; Fisher, E.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Goerdt, S.; Gordon, S.; Hamilton, J.A.; Ivashkiv, L.B.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: Nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 2014, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Han, Z.; Wu, Z.; Xia, Y.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Ren, W. GABA regulates IL-1β production in macrophages. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, W.; He, S.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Chen, N.; Dong, L.; Guo, F.; Shi, F. Scutellarin inhibits pyroptosis via selective autophagy degradation of p30/GSDMD and suppression of ASC oligomerization. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 212, 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Shi, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Zhong, Y. Formononetin ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis via enhancing antioxidant capacity, promoting tight junction protein expression and reshaping M1/M2 macrophage polarization balance. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142, 113174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaki, S.; Hojat, S.A.; Wei, B.; So, A.; Yong, W.H. An Introduction to the Performance of Immunohistochemistry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1897, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; He, S.; Shi, W.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, Z.; Li, D.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. The Neglected Role of GSDMD C-Terminal in Counteracting Type I Interferon Signaling. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e05255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Xu, W.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, D.; He, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; et al. Novel strategies for PEDV to interfere with host antiviral immunity through Caspase-1. Virulence 2025, 16, 2560890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; Quan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wen, M.; et al. Cellular spermine targets JAK signaling to restrain cytokine-mediated autoimmunity. Immunity 2024, 57, 1796–1811.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.D.; Stump, K.L.; Wallace, N.H.; Dobrzanski, P.; Serdikoff, C.; Gingrich, D.E.; Dugan, B.J.; Angeles, T.S.; Albom, M.S.; Mason, J.L.; et al. Depletion of autoreactive plasma cells and treatment of lupus nephritis in mice using CEP-33779, a novel, orally active, selective inhibitor of JAK2. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 3840–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, K.L.; Lu, L.D.; Dobrzanski, P.; Serdikoff, C.; Gingrich, D.E.; Dugan, B.J.; Angeles, T.S.; Albom, M.S.; Ator, M.A.; Dorsey, B.D.; et al. A highly selective, orally active inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, CEP-33779, ablates disease in two mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mao, J.; Yang, K.; Deng, Q.; Gao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cong, Y.; Wan, S.; Yang, W.; et al. A small-molecule enhancer of STAT1 affects herpes simplex keratitis prognosis by mediating plasmacytoid dendritic cells migration through CXCR3/CXCL10. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 147, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Hirai, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Nakajima, T.; Usui, T. Free amino acid content of lymphocytes nd granulocytes compared. Clin. Chem. 1982, 28, 1758–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learn, D.B.; Fried, V.A.; Thomas, E.L. Taurine and hypotaurine content of human leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1990, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyda, M.; Farmer, D.; Todoric, J.; Aszmann, O.; Speiser, M.; Györi, G.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Stulnig, T.M. Human adipose tissue macrophages are of an anti-inflammatory phenotype but capable of excessive pro-inflammatory mediator production. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fan, W.; Ma, Z.; Wen, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Huang, H. Taurine improves functional and histological outcomes and reduces inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience 2014, 266, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.R.; Ni, X.Q.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y.H.; Qi, Y.F. Taurine drinking ameliorates hepatic granuloma and fibrosis in mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2016, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Ishimoto, Y.; Satsu, H. Dietary taurine attenuates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced experimental colitis in mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 643, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruns, H.; Watanpour, I.; Gebhard, M.M.; Flechtenmacher, C.; Galli, U.; Schulze-Bergkamen, H.; Zorn, M.; Büchler, M.W.; Schemmer, P. Glycine and taurine equally prevent fatty livers from Kupffer cell-dependent injury: An in vivo microscopy study. Microcirculation 2011, 18, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, T.; Kim, H.W. Inhibition of apoptosis by taurine in macrophages treated with sodium nitroprusside. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 643, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y. PRMT2 silencing regulates macrophage polarization through activation of STAT1 or inhibition of STAT6. BMC Immunol. 2024, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, R.; Wei, S.; Wang, Q.; Shen, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Lu, L. Spermine Alleviates Acute Liver Injury by Inhibiting Liver-Resident Macrophage Pro-Inflammatory Response Through ATG5-Dependent Autophagy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Exogenous spermine inhibits high glucose/oxidized LDL-induced oxidative stress and macrophage pyroptosis by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhong, B.; Cao, H. Spermine suppresses GBP5-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages to relieve vital organ injuries in neonatal mice with enterovirus 71 infection. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2025, 45, 901–910. [Google Scholar]

- Hachfi, S.; Brun-Barale, A.; Fichant, A.; Munro, P.; Nawrot-Esposito, M.P.; Michel, G.; Ruimy, R.; Rousset, R.; Bonis, M.; Boyer, L.; et al. Ingestion of Bacillus cereus spores dampens the immune response to favor bacterial persistence. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Lu, C.; Wu, B.; Lan, C.; Mo, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Lan, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. Taurine Antagonizes Macrophages M1 Polarization by Mitophagy-Glycolysis Switch Blockage via Dragging SAM-PP2Ac Transmethylation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 648913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, C.; Han, J.; Cao, S.; Qian, L.; Ma, M.; Huang, S.; et al. Cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A is a signalling metabolite to control mitophagy. Nature, 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, O.H.; Knauer, S.K.; Greiner, G.; Jandt, E.; Reichardt, S.; Gührs, K.H.; Stauber, R.H.; Böhmer, F.D.; Heinzel, T. A phosphorylation-acetylation switch regulates STAT1 signaling. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, T.; Li, L.; Zhu, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; An, X.; Luo, R.; Cheng, J.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS-induced lysosomal dysfunction impairs autophagic flux and contributes to M1 macrophage polarization in a diabetic condition. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 1759–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; He, F.; Wu, X.; Tan, B.; Chen, S.; Liao, Y.; Qi, M.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. GABA transporter sustains IL-1β production in macrophages. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; He, F.; Wu, C.; Li, P.; Li, N.; Deng, J.; Zhu, G.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y. Betaine in Inflammation: Mechanistic Aspects and Applications. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, H.; Franchina, D.G.; Guerra, L.; Bonetti, L.; Baguet, L.S.; Grusdat, M.; Schlicker, L.; Hunewald, O.; Dostert, C.; Merz, M.P.; et al. Glutathione Restricts Serine Metabolism to Preserve Regulatory T Cell Function. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 920–936.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, Q.; Mi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J. Research Progress on the Interaction between Taurine Metabolism and the Gut Microbiota. Food Sci. 2025, 46, 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Öner, Ö.; Aslim, B.; Aydaş, S.B. Mechanisms of cholesterol-lowering effects of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria strains as potential probiotics with their bsh gene analysis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Grover, S.; Batish, V.K. Bile Salt Hydrolase (Bsh) Activity Screening of Lactobacilli: In Vitro Selection of Indigenous Lactobacillus Strains with Potential Bile Salt Hydrolysing and Cholesterol-Lowering Ability. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2012, 4, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Qumu, D.; Han, B.; Amatjan, M.; Wu, Q.; Wei, L.; Li, B.; Ma, M.; He, J.; et al. Taurine alleviates hyperuricemia-induced nephropathy in rats: Insights from microbiome and metabolomics. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1587198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.D.; Gai, Y.D.; Li, C.; Fu, Z.Z.; Yin, D.Q.; Xie, M.; Dai, J.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Li, Y.X.; Wu, G.F.; et al. Dietary taurine effect on intestinal barrier function, colonic microbiota and metabolites in weanling piglets induced by LPS. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1259133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polarization State | Representative Diseases | Pathological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| M1 Dominance | Sepsis, Atherosclerosis | Sustained inflammation, tissue damage |

| M2 Dominance | Cancer, Fibrotic diseases | Immunosuppression, tissue scarring |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; He, S.; Xu, W.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, S.; Ge, Y.; et al. Taurine Attenuates M1 Macrophage Polarization and IL-1β Production by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Pathway via Metabolic Reprogramming. Biology 2025, 14, 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121751

Zhang Z, Li D, He S, Xu W, Lv Q, Wang Y, Xu J, Yu Z, Liu S, Ge Y, et al. Taurine Attenuates M1 Macrophage Polarization and IL-1β Production by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Pathway via Metabolic Reprogramming. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121751

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zi’an, Danyue Li, Suhui He, Weilv Xu, Qian Lv, Yumeng Wang, Jinxia Xu, Zexu Yu, Shiyang Liu, Yuanxiang Ge, and et al. 2025. "Taurine Attenuates M1 Macrophage Polarization and IL-1β Production by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Pathway via Metabolic Reprogramming" Biology 14, no. 12: 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121751

APA StyleZhang, Z., Li, D., He, S., Xu, W., Lv, Q., Wang, Y., Xu, J., Yu, Z., Liu, S., Ge, Y., Shi, F., & Yan, Y. (2025). Taurine Attenuates M1 Macrophage Polarization and IL-1β Production by Suppressing the JAK1/2-STAT1 Pathway via Metabolic Reprogramming. Biology, 14(12), 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121751