Milk Disposition Kinetics, Residue and Efficacy of Rifaximin After Intramammary Administration in Lactating Cow

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization of Sample Extraction

2.2. Selection and Optimization of Chromatographic Conditions

2.3. Optimization of Mass Spectrometry Conditions

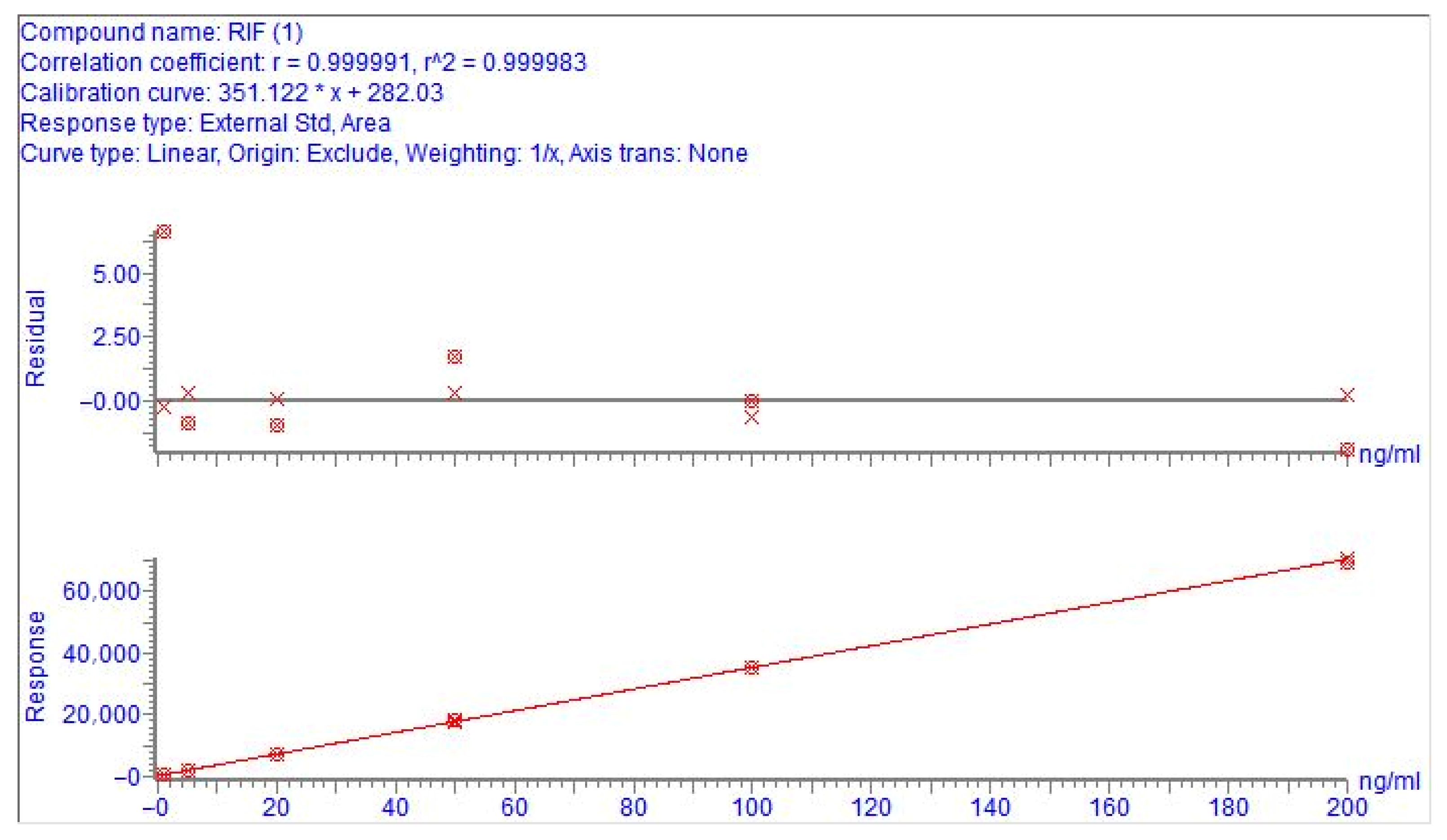

2.4. Method Validation

2.4.1. Selectivity and Matrix Effect

2.4.2. Linearity

2.4.3. LOD and LOQ

2.4.4. Precision and Accuracy

2.4.5. Stability

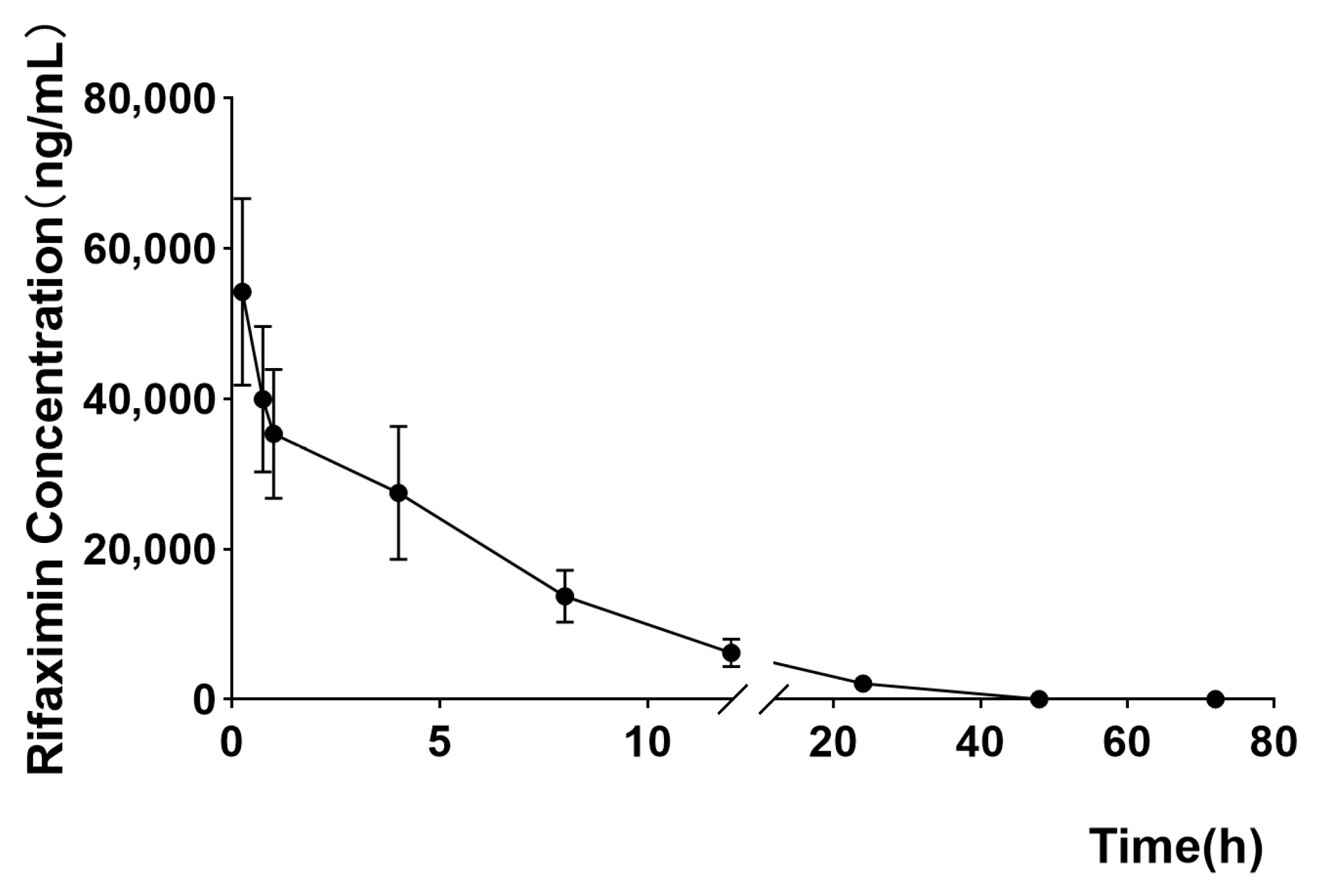

2.5. Milk Disposition Kinetics Results

2.6. Residue Results

2.7. Clinical Cure

2.8. Bacteriological Cure

2.9. Results of Milk Somatic Cell Counts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Materials

3.2. Sample Preparation

3.3. UPLC-MS/MS Conditions

3.4. Results of Method Validation

3.4.1. Selectivity and Matrix Effect

3.4.2. Linearity

3.4.3. LOD and LOQ

3.4.4. Precision and Accuracy

3.4.5. Stability

3.5. Animal Experiment

3.5.1. Milk Disposition Kinetics Study

3.5.2. Residue Experiment

3.5.3. Efficacy Experiment

3.5.4. Animals’ Treatment

3.5.5. Assessment of Severity of Clinical Mastitis

3.5.6. Assessment of Bacteriological Cure

3.5.7. Assessment of Somatic Cell Counts

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| AUMC | Area under the moment curve |

| MRT | Mean residue time |

| Cmax | the peak concentration |

| Tmax | the peak time |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantifications |

| MRLs | Maximum residue limits |

| ME | Matrix effect |

| DIM | Days in milk |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| SCC | Somatic cell count |

| CS | Clinical scores |

References

- Raboisson, D.; Ferchiou, A.; Pinior, B.; Gautier, T.; Sans, P.; Lhermie, G. The Use of Meta-Analysis for the Measurement of Animal Disease Burden: Losses Due to Clinical Mastitis as an Example. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, M.; Haine, D.; Kelton, D.F.; Barkema, H.W.; Hogeveen, H.; Keefe, G.P.; Dufour, S. Herd-Level Mastitis-Associated Costs on Canadian Dairy Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasa, T.; Huijps, K.; Osterås, O.; Hogeveen, H. Economic effects of bovine mastitis and mastitis management: A review. Vet. Q. 2007, 29, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, R.; Hatiya, H.; Abera, M.; Megersa, B.; Asmare, K. Bovine mastitis: Prevalence, risk factors and isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy herds at Hawassa milk shed, South Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.K.; Gay, J.M. Contagious mastitis. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1993, 9, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, R.D.; Gillespie, B.E.; Ivey, S.; Pighetti, G.M.; Almeida, R.A.; Kerro Dego, O. Antimicrobial Resistance of Major Bacterial Pathogens from Dairy Cows with High Somatic Cell Count and Clinical Mastitis. Animals 2021, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Tiwari, R.; Gugjoo, M.B.; Yatoo, M.I.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Karthik, K.; Khurana, S.K.; Singh, R.; et al. Advances in therapeutic and managemental approaches of bovine mastitis: A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2021, 41, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatta, L.; Scarpignato, C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistiki, A.; Galani, I.; Pyleris, E.; Barbatzas, C.; Pimentel, M.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. In vitro activity of rifaximin against isolates from patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W.W.; Gerlach, E.H.; Hoban, D.J.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Pfaller, M.A.; Jones, R.N. Antimicrobial activity and spectrum of rifaximin, a new topical rifamycin derivative. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1993, 16, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K.L.; Mushtaq, S.; Richardson, J.F.; Doumith, M.; de Pinna, E.; Cheasty, T.; Wain, J.; Livermore, D.M.; Woodford, N. In vitro activity of rifaximin against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and other enteropathogenic bacteria isolated from travellers returning to the UK. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, J.C.; Brogden, R.N. Rifaximin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in conditions mediated by gastrointestinal bacteria. Drugs 1995, 49, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

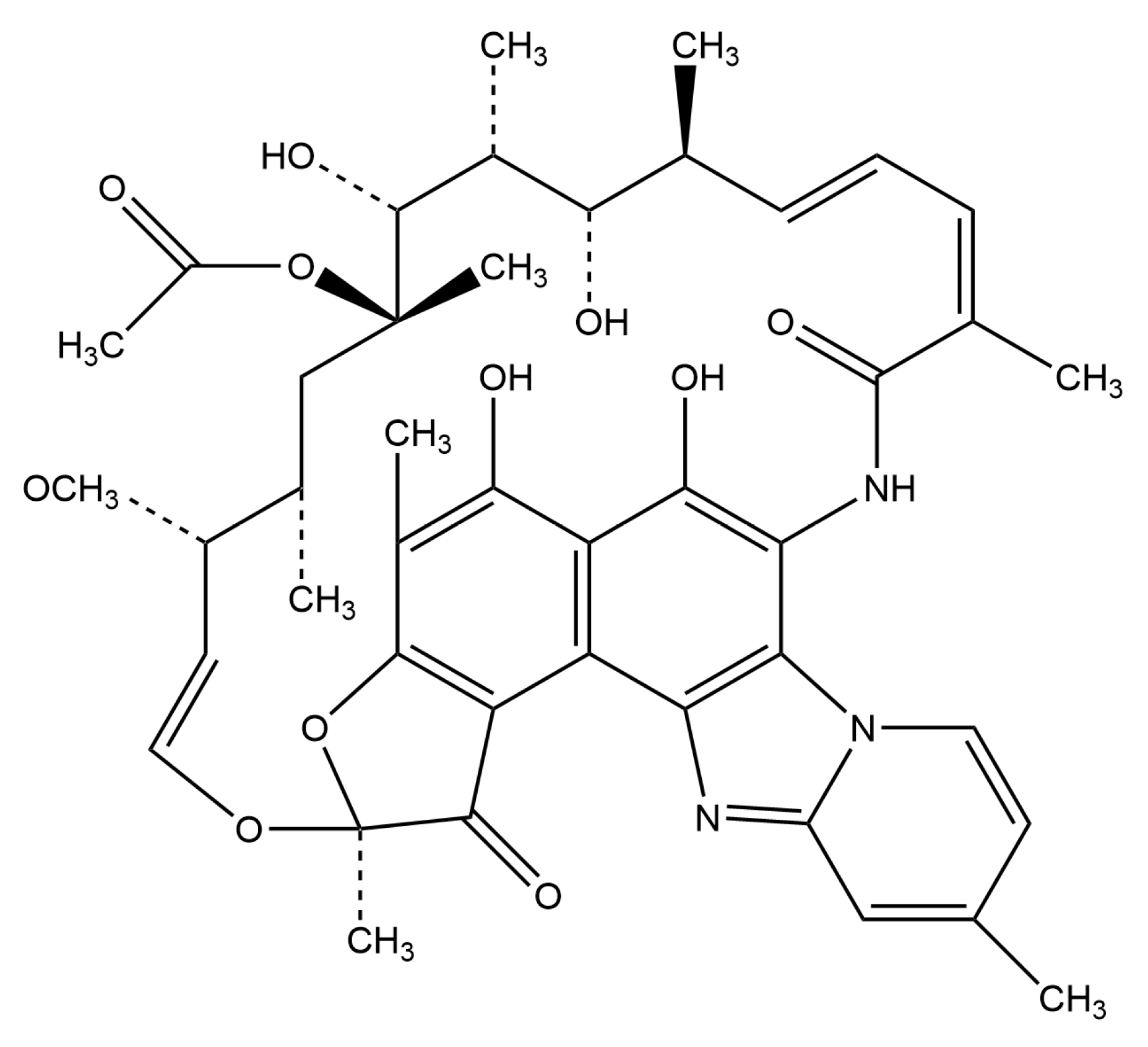

- Martini, S.; Bonechi, C.; Corbini, G.; Donati, A.; Rossi, C. Solution structure of rifaximin and its synthetic derivative rifaximin OR determined by experimental NMR and theoretical simulation methods. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.M.; Sayuk, G.S. Current US Food and Drug Administration-Approved Pharmacologic Therapies for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottreau, J.; Baker, S.F.; DuPont, H.L.; Garey, K.W. Rifaximin: A nonsystemic rifamycin antibiotic for gastrointestinal infections. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2010, 8, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, N.M.; Mullen, K.D.; Sanyal, A.; Poordad, F.; Neff, G.; Leevy, C.B.; Sigal, S.; Sheikh, M.Y.; Beavers, K.; Frederick, T.; et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, A.; Dall’Aglio, M.; Quintavalla, F.; Dallavalle, L.; Meucci, V.; Bertini, S. Rifaximin is an effective alternative to metronidazole for the treatment of chronic enteropathy in dogs: A randomised trial. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammini, L.; Mantelli, L.; Volpe, A.; Domenichini, G.; Di Lecce, R.; Dondi, M.; Cantoni, A.M.; Barocelli, E.; Quintavalla, F. Rifaximin anti-inflammatory activity on bovine endometrium primary cell cultures: A preliminary study. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 4, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmund, M.; Egger-Danner, C.; Firth, C.L.; Obritzhauser, W.; Roch, F.F.; Conrady, B.; Wittek, T. The effect of antibiotic versus no treatment at dry-off on udder health and milk yield in subsequent lactation: A retrospective analysis of Austrian health recording data from dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjarrez, J.L.A.; Téllez, S.A.; Martínez, R.R.; Hernández, V.O.F. Determination of rifaximine in milk of dairy cows using high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Rev. Cient.-Fac. Cienc. Vet. 2012, 22, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Buldain, D.; Castillo, L.G.; Buchamer, A.V.; Aliverti, F.; Bandoni, A.; Marchetti, L.; Mestorino, N. Melaleuca armillaris Essential Oil in Combination With Rifaximin Against Staphylococcus aureus Isolated of Dairy Cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, F.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. A Lactation-Period Compound Antibacterial Preparation and Its Preparation Method and Application. CN109432092B, 9 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Che, Y.; He, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; You, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, D.W.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; et al. Veterinary Suspoemulsion Containing Rifaximin and Its Preparation Method and Application. CN104083324B, 10 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Yu, Z. Rifaximin Intramammary In-Situ Gel and Its Preparation Method and Application. CN105232450B, 17 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Girardello, G.P.; Signorini, G.C.; Vallisneri, A. Rifaximin in the tretment and prevention of dry cow mastitis. La rifaximina nella terapia e prevenzione delle mastiti bovine in asciutta. Obiettivi Doc. Vet. 1987, 8, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Avila, T.S.; Rivera, A.R.; Angeles, M.J.L.; Rosiles, R.M.; Navarro, H.J.A. Prevention of mastitis in dairy cows by application of rifaximin during the dry period. Veterinarstvi 2009, 59, 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Dong, J.; Kong, M.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y. Rifaximin-Containing Preparation for Preventing and Treating Dairy Cow Mastitis During the Dry Period. CN102716168B, 12 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Gao, R.; Jiao, W.; Jiao, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, G.; Zhen, P.; Zhu, S.; et al. Rifaximin–Houttuynia Cordata Intramammary Perfusion Agent and Its Preparation Method. CN103263523B, 28 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van den Anker, J.; Reed, M.D.; Allegaert, K.; Kearns, G.L. Developmental Changes in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, S10–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descombe, J.J.; Dubourg, D.; Picard, M.; Palazzini, E. Pharmacokinetic study of rifaximin after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 1994, 14, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.D.; Ke, S.; Palazzini, E.; Riopel, L.; Dupont, H. In vitro activity and fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2205–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacanlı, M.; Başaran, N. Importance of antibiotic residues in animal food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñeiro, S.A.; Cerniglia, C.E. Antimicrobial drug residues in animal-derived foods: Potential impact on the human intestinal microbiome. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 44, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogawa, A.C.; Salgado, H.R.N. Status of Rifaximin: A Review of Characteristics, Uses and Analytical Methods. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 48, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Song, G.; Ai, L.F.; Li, J.C. Determination of six polyether antibiotic residues in foods of animal origin by solid phase extraction combined with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1017, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, L.; Hoff, R.B.; Tarouco, P.C.; Barreto, F.; Pizzolato, T.M. β-lactam antibiotics residues analysis in bovine milk by LC-ESI-MS/MS: A simple and fast liquid-liquid extraction method. Food Addit. Contam. Part A-Chem. 2012, 29, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jank, L.; Martins, M.T.; Arsand, J.B.; Motta, T.M.C.; Feijó, T.C.; Castilhos, T.D.; Hoff, R.; Barreto, F.; Pizzolato, T.M. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Multiclass Method for 46 Antibiotics Residues in Milk and Meat: Development and Validation. Food Anal. Meth. 2017, 10, 2152–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Viceo, J.A.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; Guillén-Casla, V.; Pérez-Arribas, L.V.; León-González, M.E.; Polo-Díez, L.M. Fluoroquinolone antibiotic determination in bovine milk using capillary liquid chromatography with diode array and mass spectrometry detection. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 28, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P.; Jelińska, A.; Garbacki, P. UHPLC: The Greening Face of Liquid Chromatography. Chromatographia 2013, 76, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C. Application of column characterization systems in selecting optimal RP-HPLC columns. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2017, 37, 942–949. [Google Scholar]

- Cajka, T.; Hricko, J.; Kulhava, L.R.; Paucova, M.; Novakova, M.; Kuda, O. Optimization of Mobile Phase Modifiers for Fast LC-MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics and Lipidomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.L.; Wu, Y.L.; Lv, Y.; Xu, X.Q.; Zhao, J.; Yang, T. Development and validation of an ultra high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for determination of 10 cephalosporins and desacetylcefapirin in milk. J. Chromatogr. B 2013, 931, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMEA/CVMP. Guideline for the Conduct of Efficacy Studies for Intramammary Products for Use in Cattle; EMEA/CVMP/344/99-FINAL-Rev.1; EMEA: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- VICH/EMA. VICH GL48(R). Studies to Evaluate the Metabolism and Residue Kinetics of Veterinary Drugs in Food-Producing Animals: Marker Residue Depletion Studies to Establish Product Withdrawal Periods; EMA: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.C. Milk nutritional composition and its role in human health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Lopez, R.A.; Zhu, C.; Liu, Y.M. Consumer preferences for sustainably produced ultra-high-temperature milk in China. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.R.; Cleale, R.M.; Jardon, G.; Short, T.; Mills, B.; Pedraza, J.R. Outcomes after treatment of nonsevere gram-negative clinical mastitis with ceftiofur hydrochloride for 2 or 5 days compared with negative control. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 2390–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinkels, J.M.; Krömker, V.; Lam, T.J. Efficacy of standard vs. extended intramammary cefquinome treatment of clinical mastitis in cows with persistent high somatic cell counts. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 81, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calanni, F.; Renzulli, C.; Barbanti, M.; Viscomi, G.C. Rifaximin: Beyond the traditional antibiotic activity. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.D.; DuPont, H.L. Rifaximin: In vitro and in vivo Antibacterial Activity—A Review. Chemotherapy 2005, 51, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.; Pickering, A.C.; Rocha, L.S.; Aguilar, A.P.; Fabres-Klein, M.H.; de Oliveira Mendes, T.A.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; de Oliveira Barros Ribon, A. Diversity and pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis: Current understanding and future perspectives. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, N.W.M.; Van Kessel, K.P.M.; Van Strijp, J.A.G. Immune Evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Chen, X.; Shang, F. Short communication: Effects of lactose and milk on the expression of biofilm-associated genes in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from a dairy cow with mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 6129–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneau, J.K. Effective use of dairy herd improvement somatic cell counts in mastitis control. J. Dairy Sci. 1986, 69, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohoo, I.R.; Meek, A.H. Somatic cell counts in bovine milk. Can. Vet. J. 1982, 23, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, R.J. Somatic cell counts: A primer. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting-National Mastitis Council Incorporated, Reno, NV, USA, 11–14 February 2001; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, S.; Paduch, J.H.; Hoedemaker, M.; Krömker, V. Factors affecting the probability of bacteriological cure of bovine mastitis. Tieraerztl. Prax. Ausg. Grosstiere Nutztiere 2015, 43, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2002/657/EC: Commission Decision of 12 August 2002 Implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC Concerning the Performance of Analytical Methods and the Interpretation of Results. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2002/657/oj (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FDA. CVM GFI #49 Target Animal Safety and Drug Effectiveness Studies for Anti-Microbial Bovine Mastitis Products (Lactating and Non-Lactating Cow Products); Docket No. 93D-0025; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Canning, P.; Hassfurther, R.; TerHune, T.; Rogers, K.; Abbott, S.; Kolb, D. Efficacy and clinical safety of pegbovigrastim for preventing naturally occurring clinical mastitis in periparturient primiparous and multiparous cows on US commercial dairies. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 6504–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, D.E.; Shanks, R.D.; McCoy, G.C. Comparison of antibiotic administration in conjunction with supportive measures versus supportive measures alone for treatment of dairy cows with clinical mastitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1998, 213, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, A.K.; Nydam, D.V.; Capel, M.B.; Ceglowski, B.; Rauch, B.J.; Thomas, M.J.; Tikofsky, L.; Watters, R.D.; Zuidhof, S.; Zurakowski, M.J. Randomized noninferiority trial comparing 2 commercial intramammary antibiotics for the treatment of nonsevere clinical mastitis in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8267–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacterial Isolated from Animals; Approved Standard-Fourth Edition and Supplement; Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Milk Kinetics Parameters | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (h⋅ng/mL) | 340,731.8 | 43,968.82 |

| T1/2 (h) | 5.5748 | 0.68 |

| λz (1/h) | 0.1262 | 0.0166 |

| MRT (h) | 7.3927 | 1.3353 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 54,273.33 | 12,421.32 |

| AUMC (h⋅h⋅ng/mL) | 2,475,745 | 230,305.1 |

| Time (h) | Mean ± SD (μg/kg) |

|---|---|

| 12 | 120,354 ± 39,209.74 |

| 18 | 68,770 ± 27,069.78 |

| 24 | 32,250 ± 13,478.23 |

| 36 | 14,756 ± 5858.79 |

| 42 | 6206 ± 2367.47 |

| 48 | 2373 ± 919.33 |

| 60 | 893.35 ± 217.35 |

| 66 | 409.05 ± 104.78 |

| 72 | 191.66 ± 63.82 |

| 84 | 68.1 ± 14.62 |

| 90 | 32.86 ± 9.90 |

| 96 | 14.86 ± 6.56 |

| 108 | 2.57 ± 2.10 |

| Day | RIF Cure Rate | LCM Cure Rate | p Value | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D4 | 20.00% (6/30) | 13.33% (4/30) | 0.490 | 0.476 |

| D5 | 43.33% (13/30) | 20.00% (6/30) | 0.048 | 3.913 |

| D6 | 66.67% (20/30) | 43.33% (13/30) | 0.048 | 3.333 |

| D7 | 80.00% (24/30) | 66.67% (20/30) | 0.243 | 1.364 |

| D12 | 83.33% (25/30) | 73.33% (22/30) | 0.359 | 0.842 |

| Pathogen | Group | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D − 1 | D0 | D14 | D21 | ||

| Escherichia coli | rifaximin | 83.33% | 83.33% | 6.67% | 6.67% |

| lincomycin | 90.00% | 90.00% | 16.67% | 16.67% | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | rifaximin | 13.33% | 13.33% | 10.00% | 10.00% |

| lincomycin | 16.67% | 16.67% | 16.67% | 16.67% | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | rifaximin | 10.00% | 10.00% | 6.67% | 6.67% |

| lincomycin | 6.67% | 6.67% | 6.67% | 6.67% | |

| Run Time (min) | Eluent A (%) | Eluent B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 70.00 | 30.00 |

| 3.00 | 20.00 | 80.00 |

| 4.50 | 70.00 | 30.00 |

| Parameter | Settings |

|---|---|

| Ionization mode | Electrospray ionization (positive mode) |

| Capillary voltage | 2.0 kV |

| Ion source temperature | 150 °C |

| Desolvation temperature | 400 °C |

| Cone gas flow | 50 L/h |

| Desolvation gas flow | 800 L/h |

| Secondary collision gas | Ar2 |

| Precursorion (m/z) | Production (m/z) | Cone Voltage (V) | Collision Energy (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 786.6 | 150.8 | 30 | 50 |

| 754.7 * | 30 | 50 |

| Observations | Appearance of Milk/Quarter | Clinical Score |

|---|---|---|

| milk | Normal | 0 |

| Suspect (few transient flakes or clots) or small amounts of flocs | 1 | |

| Milk with large clots, flakes, or discoloration | 2 | |

| Milk with blood and/or pus, distinct odor | 3 | |

| quarter | Normal | 0 |

| Slight inflammation/swelling, warm to the touch, or both | 1 | |

| Moderate inflammation/swelling, hot to the touch, or both | 2 | |

| Severe inflammation/swelling, hot to the touch, or both | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, N.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xiang, J.; Qu, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y. Milk Disposition Kinetics, Residue and Efficacy of Rifaximin After Intramammary Administration in Lactating Cow. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121203

Yu N, Tang Y, Zhao W, Xiang J, Qu J, Wu H, Liu Y. Milk Disposition Kinetics, Residue and Efficacy of Rifaximin After Intramammary Administration in Lactating Cow. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121203

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Na, Yaoxin Tang, Weifeng Zhao, Junhao Xiang, Jing Qu, Hao Wu, and Yiming Liu. 2025. "Milk Disposition Kinetics, Residue and Efficacy of Rifaximin After Intramammary Administration in Lactating Cow" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121203

APA StyleYu, N., Tang, Y., Zhao, W., Xiang, J., Qu, J., Wu, H., & Liu, Y. (2025). Milk Disposition Kinetics, Residue and Efficacy of Rifaximin After Intramammary Administration in Lactating Cow. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121203