Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli, and Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium in the Production Environment and Among Workers in Low-Capacity Slaughterhouses in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Characteristics of the Studied Population of Workers

2.2. Occurrence of ESBL-E. coli, MRSA, and VRE-E. faecium

2.3. Characteristics of ESBL-E. coli Isolates

2.3.1. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of ESBL-E. coli Isolates

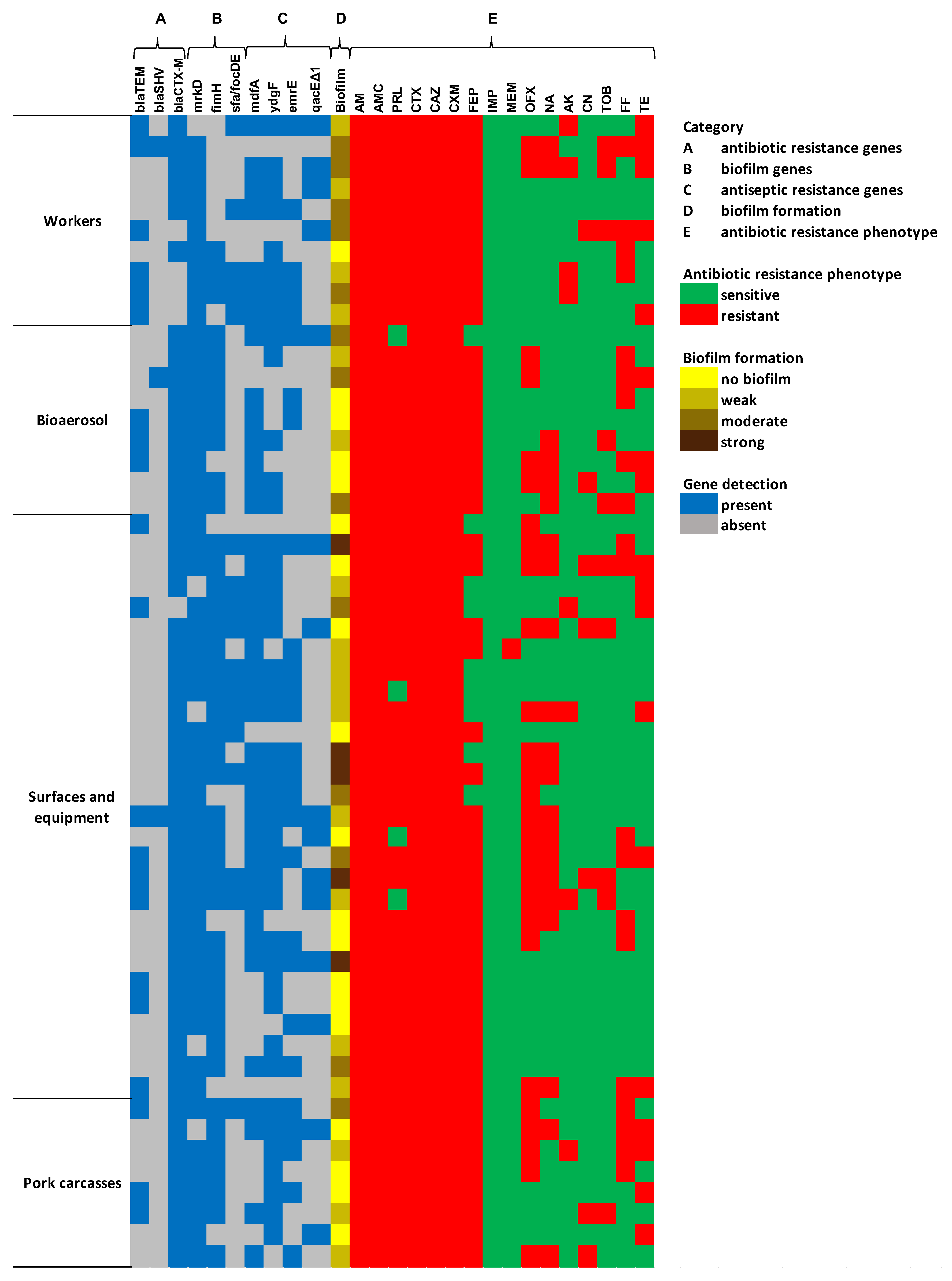

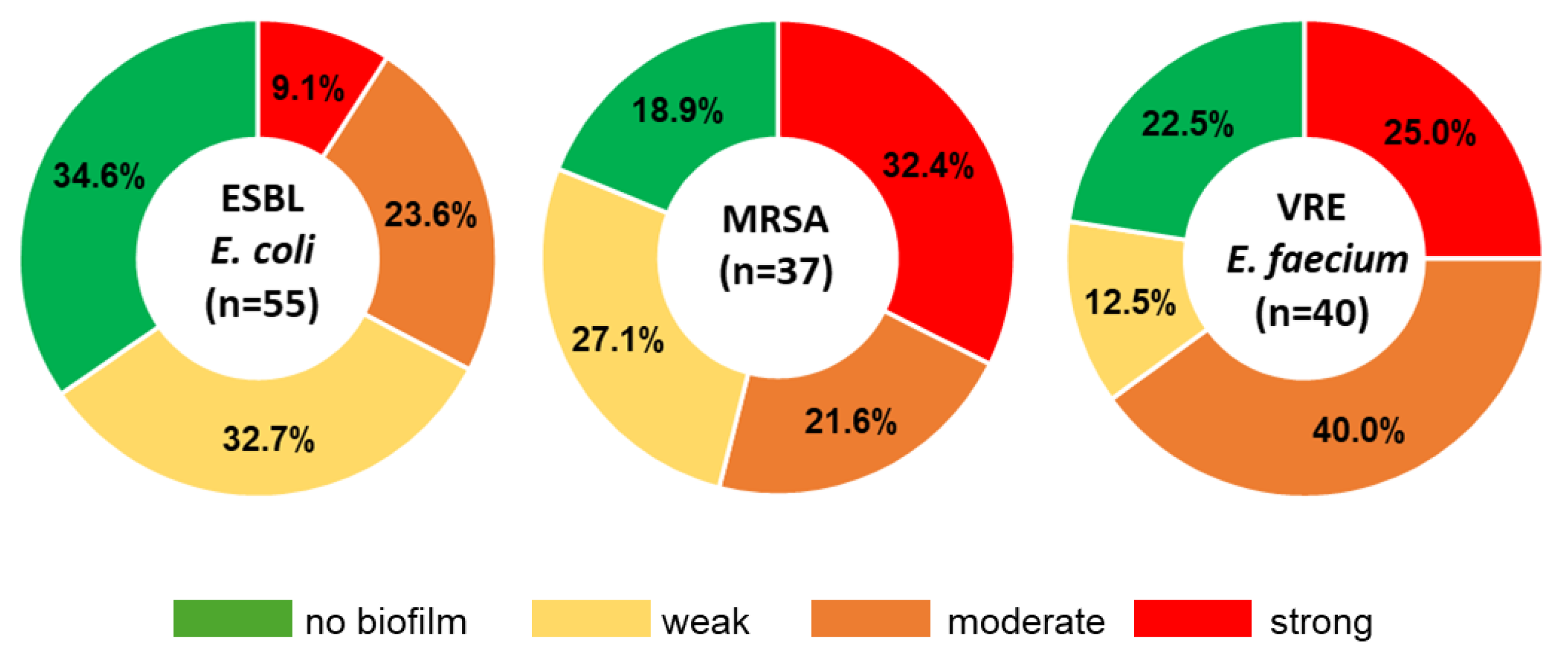

2.3.2. Genetic Characterization and Biofilm Formation Potential of ESBL-E. coli

2.4. Characteristics of MRSA Isolates

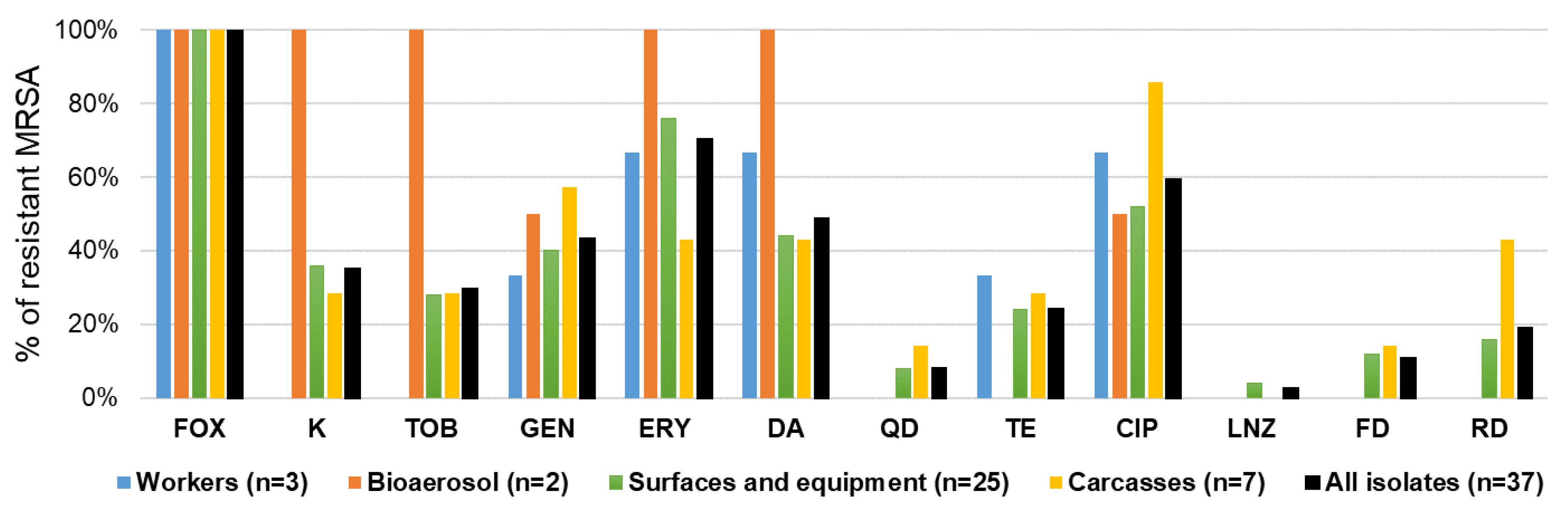

2.4.1. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of MRSA Isolates

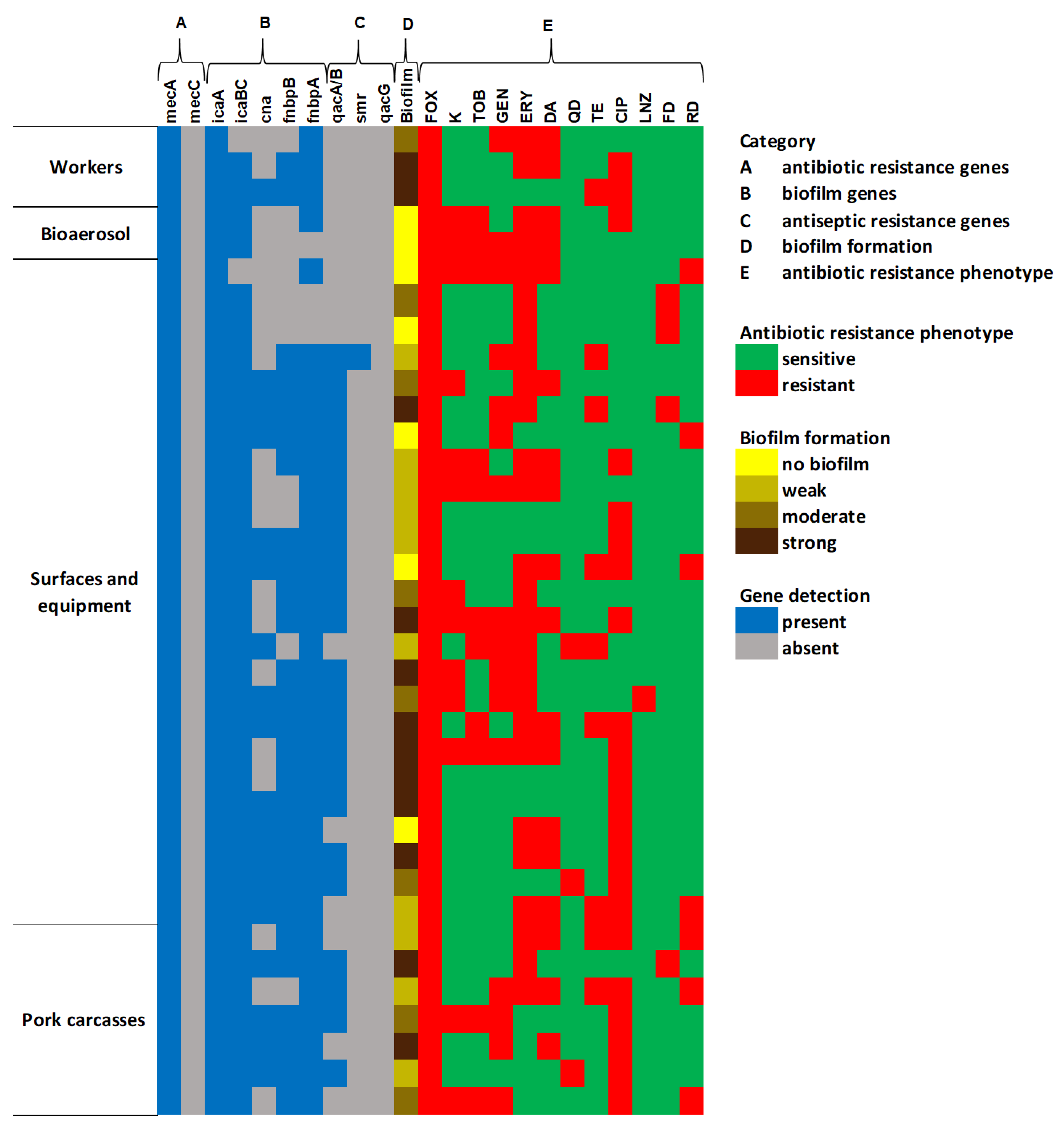

2.4.2. Genetic Characterization and Biofilm Formation Potential of MRSA

2.5. Characteristics of VRE-E. faecium Isolates

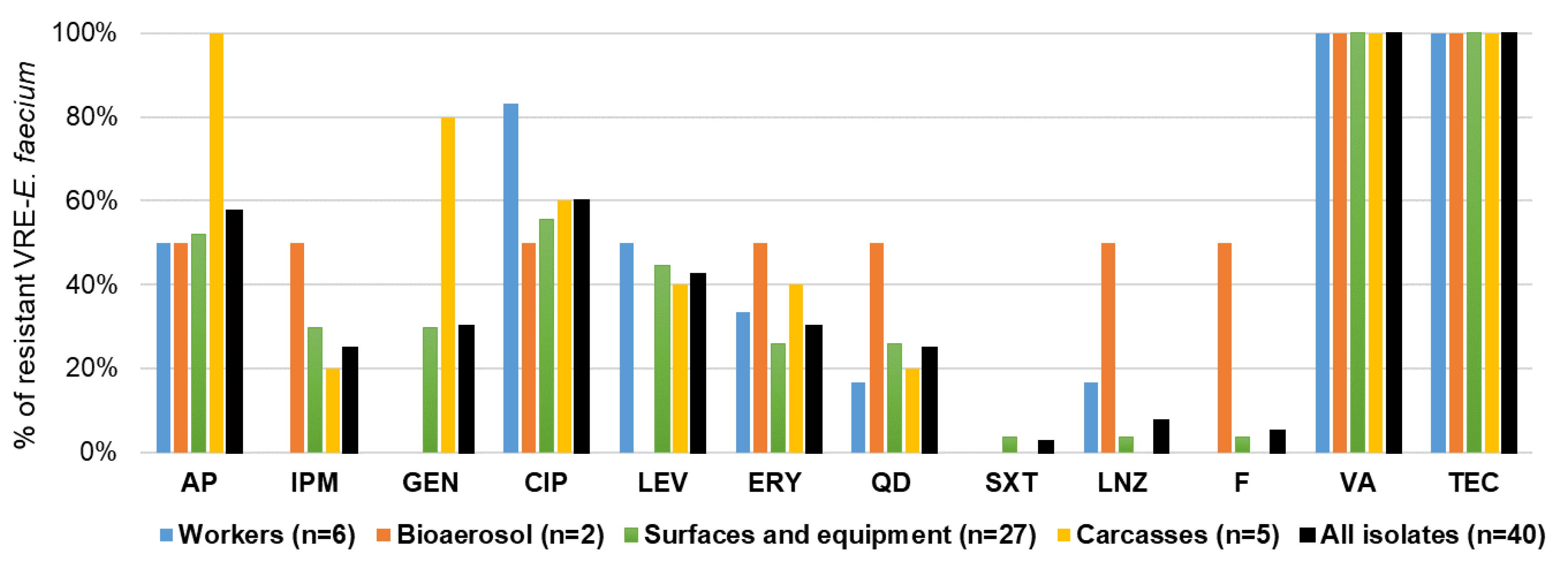

2.5.1. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of VRE-E. faecium Isolates

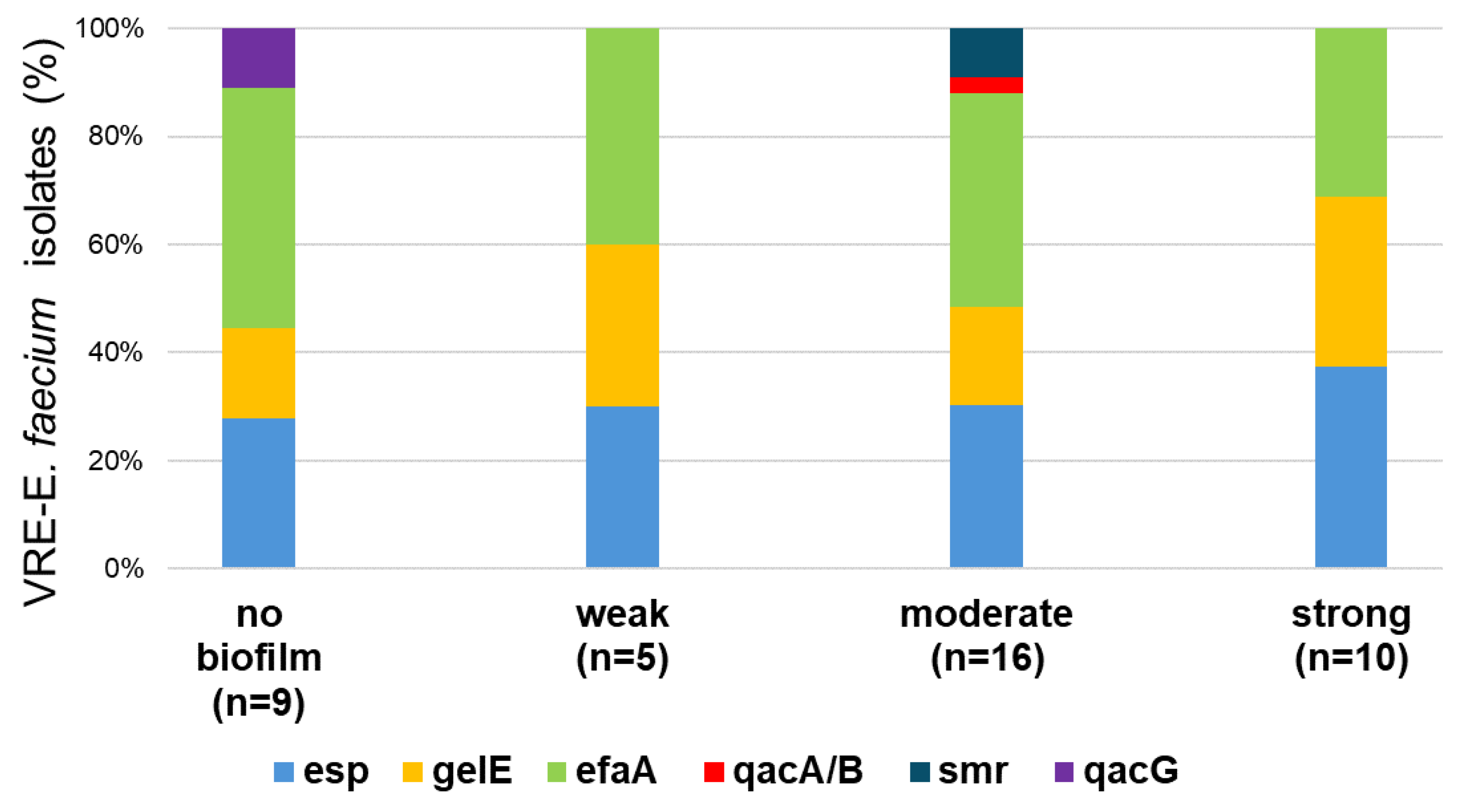

2.5.2. Genetic Characterization and Biofilm Formation Potential of VRE Isolates

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Collection of Biological Samples and Questionnaire Study

4.3. Bioaerosol Measurement

4.4. Swabbing from Meat Production Line

4.5. Microbial Analysis

4.6. Phenotypic Characterizations MRSA, ESBL-E.coli, and VRE-E. faecium

4.7. Detection of Biofilm-Forming Abilities of MRSA, ESBL-E.coli, and VRE-E. faecium

4.8. Genotypic Characterizations of MRSA, ESBL-E.coli, and VRE-E. faecium

4.9. Data Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases |

| MARI | Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Index |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSSA | Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| non-ESBLs | Isolates that do not produce ESBL enzyme |

| VRE | Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus |

| VSE | Vancomycin-Sensitive Enterococcus |

References

- Morehead, M.S.; Scarbrough, C. Emergence of global antibiotic resistance. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2018, 45, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiseo, K.; Huber, L.; Gilbert, M.; Robinson, T.P.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, S.; Queiroga, M.C.; Laranjo, M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Meat and Meat Products: A One Health Perspective. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Sales and Use of Antimicrobials for Veterinary Medicine (ESUAvet). Annual Surveillance Report for 2023’ (EMA/CVMP/ESUAVET/80289/2025). 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/european-sales-use-antimicrobials-veterinary-medicine-annual-surveillance-report-2023_en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Akkaya, L.; Alisarli, M.; Cetinkaya, Z.; Kara, R.; Telli, R. Occurrence of Escherichia colio157:H7/O157, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. in beef slaughterhouse environments, equipment and workers. J. Muscle Foods 2008, 19, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klous, G.; Huss, A.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Coutinho, R.A. Human-livestock contacts and their relationship to transmission of zoonotic pathogens, a systematic review of literature. One Health 2016, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Leahy, K.; Resnick, C.; Howard, T.; Carroll, K.C.; Silbergeld, E.K. Exposure to pathogens among workers in a poultry slaughter and processing plant. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, W.; VAN Gompel, L.; Schmitt, H.; Liakopoulos, A.; Heres, L.; Urlings, B.A.; Mevius, D.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Heederik, D.J.J. ESBL carriage in pig slaughterhouse workers is associated with occupational exposure. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Li, L.; Li, S.M.; Huang, J.Y.; Fan, Y.P.; Yao, Z.J.; Ye, X.H.; Chen, S.D. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in slaughterhouse pig-related workers and control workers in Guangdong Province, China. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aworh, M.K.; Abiodun-Adewusi, O.; Mba, N.; Helwigh, B.; Hendriksen, R.S. Prevalence and risk factors for faecal carriage of multidrug resistant Escherichia coli among slaughterhouse workers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkiewicz, J.; Cisak, E.; Sroka, J.; Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Zając, V. Biological agents as occupational hazards-selected issues. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2011, 18, 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kasaeinasab, A.; Jahangiri, M.; Karimi, A.; Tabatabaei, H.R.; Safari, S. Respiratory Disorders Among Workers in Slaughterhouses. Saf. Health Work 2017, 8, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveland, H.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heesterbeek, H.; Mevius, D.; van Duijkeren, E.; Heederik, D. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in veal calf farming: Human MRSA carriage related with animal antimicrobial usage and farm hygiene. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, N.; Udarcev, S.; Müller, H.; Kobusch, I.; Linnemann, S.; Boelhauve, M.; Köck, R.; Mellmann, A. Genotypic Characterization of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates of Clonal Complex 398 in Pigsty Visitors: Transient Carriage or Persistence? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 58, e01276-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köck, R.; Schaumburg, F.; Mellmann, A.; Köksal, M.; Jurke, A.; Becker, K.; Friedrich, A.W. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as causes of human infection and colonization in Germany. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, M.K.; Ekeng, E.; Nilsson, P.; Egyir, B.; Owusu-Nyantakyi, C.; Hendriksen, R.S. Extended-Spectrum ß-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Among Humans, Beef Cattle, and Abattoir Environments in Nigeria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 869314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, W.; Kolte, B.; Junker, V.; Frentrup, M.; Dolsdorf, C.; Börger, M.; Jaleta, M.; Kabelitz, T.; Amon, T.; Werner, D.; et al. Bacterial genome sequencing tracks the housefly-associated dispersal of fluoroquinolone- and cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from a pig farm. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Skowron, K.; Bauza-Kaszewska, J.; Budzyńska, A.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Wilk, M.; Wujak, M.; Paluszak, Z. Assessment of antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation of Enterococcus species isolated from different pig farm environments in Poland. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, H.; Friese, A.; von Salviati, C.; Guerra, B.; Rösler, U. Transmission of ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from broiler chicken farms to surrounding areas. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 172, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, W.; Bonten, M.; Bos, M.; Van Marm, S.; Scharringa, J.; Wagenaar, J.; Heederik, D. Carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in pig farmers is associated with occurrence in pigs. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, W.; Schmitt, H.; Bonten, M.; Heederik, D. Air exposure as a possible route for ESBL in pig farmers. Environ. Res. 2017, 155, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadepohl, K.; Müller, A.; Seinige, D.; Rohn, K.; Blaha, T.; Meemken, D.; Kehrenberg, C. Association of intestinal colonization of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in poultry slaughterhouse workers with occupational exposure-A German pilot study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, R.M.; Biggs, P.J.; Burgess, S.A.; Midwinter, A.C.; Brightwell, G.; Cookson, A.L. Prevalence and distribution of extended-spectrum β-lactamase and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli in two New Zealand dairy farm environments. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 960748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cleef, B.A.; Broens, E.M.; Voss, A.; Huijsdens, X.W.; Züchner, L.; Van Benthem, B.H.; Kluytmans, J.A.; Mulders, M.N.; Van De Giessen, A.W. High prevalence of nasal MRSA carriage in slaughterhouse workers in contact with live pigs in The Netherlands. Epidemiol. Infect. 2010, 138, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.J.; Bos, M.E.; Duim, B.; Urlings, B.A.; Heres, L.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Heederik, D.J. Livestock-associated MRSA ST398 carriage in pig slaughterhouse workers related to quantitative environmental exposure. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascaro, V.; Leonetti, M.; Nobile, C.G.A.; Barbadoro, P.; Ponzio, E.; Recanatini, C.; Prospero, E.; Pavia, M. Collaborative Working Group Prevalence of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) Among Farm and Slaughterhouse Workers in Italy. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e416–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Long, J.; Duan, G.; Yang, H. Transmission of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between animals, environment, and humans in the farm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 86521–86539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordoncillo, M.J.; Donabedian, S.; Bartlett, P.C.; Perri, M.; Zervos, M.; Kirkwood, R.; Febvay, C. Isolation and molecular characterization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from swine in Michigan, USA. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Cyprowski, M.; Górny, R.L. Distribution of Selected Drug-resistant Enterococcus Species in Meat Plants in Poland. Rocz. Ochr. Sr. 2022, 24, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, L.; Rega, M.; Bonilauri, P.; Pupillo, G.; De Lorenzi, G.; Bonardi, S.; Conter, M.; Bacci, C. Vancomycin resistance and virulence genes evaluation in Enterococci isolated from pork and wild boar meat. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.M. The role of bacterial biofilm in antibiotic resistance and food contamination. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 1705814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, S.; De Luca, S.; Rodríguez-López, P.; Simon, A.C.; Liuzzo, G.; Poli, L.; Ianieri, A.; Zanardi, E. Microbial contamination, antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation of bacteria isolated from a high-throughput pig abattoir. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridier, A.; Briandet, R.; Thomas, V.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to disinfectants: A review. Biofouling 2011, 27, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.M.; Pomba, C.; Lopes, M.F. High-level vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium related to humans and pigs found in dust from pig breeding facilities. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 161, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feld, L.; Bay, H.; Angen, Ø.; Larsen, A.R.; Madsen, A.M. Survival of LA-MRSA in Dust from Swine Farms. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2018, 62, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, Y.; Yushina, Y.; Mardanov, A.; Gruzdev, E.; Tikhonova, E.; El-Registan, G.; Beletskiy, A.; Semenova, A.; Zaiko, E.; Bataeva, D.; et al. Microbial Biofilms at Meat-Processing Plant as Possible Places of Bacteria Survival. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban-Cucerzan, A.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Marcu, A.; Hotea, I.; Popa, S.-A.; Pătrînjan, R.-T.; Bucur, I.-M.; Gașpar, C.; Plotuna, A.-M.; et al. Persistent Threats: A Comprehensive Review of Biofilm Formation, Control, and Economic Implications in Food Processing Environments. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Khurshid, M.; Arshad, M.I.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.; Yasmeen, N.; Shah, T.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Rasool, M.H.; Shahid, A.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 771510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florez-Cuadrado, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Ugarte-Ruíz, M.; Domínguez, L. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain in the European Union. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 86, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiary, F.; Sayevand, H.R.; Remely, M.; Hippe, B.; Hosseini, H.; Haslberger, A.G. Evaluation of bacterial contamination sources in meat production line. J. Food Qual. 2016, 39, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, R.; Sun, Y.; Yang, X.; Yao, J. Tracing enterococci persistence along a pork production chain from feed to food in China. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 9, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, M.; Yang, D.; Joosten, P.; Munk, P.; Wadepohl, K.; Chauvin, C.; Moyano, G.; Skarżyńska, M.; Dewulf, J.; Aarestrup, F.M.; et al. Risk Factors for Antimicrobial Resistance in Turkey Farms: A Cross-Sectional Study in Three European Countries. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.P.; Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Trueba, G.; Zhang, L.; Johnson, T.J. Small-Scale Food Animal Production and Antimicrobial Resistance: Mountain, Molehill, or Something in-between? Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losito, P.; Visciano, P.; Genualdo, M.; Satalino, R.; Migailo, M.; Ostuni, A.; Luisi, A.; Cardone, G. Evaluation of hygienic conditions of food contact surfaces in retail outlets: Six years of monitoring. LWT 2016, 77, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivbule, M.; Miklaševičs, E.; Čupāne, L.; Bērziņa, L.; Bālinš, A.; Valdovska, A. Presence of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Slaughterhouse Environment, Pigs, Carcasses, and Workers. J. Vet. Res. 2017, 61, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langkabel, N.; Burgard, J.; Freter, S.; Fries, R.; Meemken, D.; Ellerbroek, L. Detection of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) E. coli at Different Processing Stages in Three Broiler Abattoirs. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Nathaus, R.; Layer, F.; Strommenger, B.; Altmann, D.; Witte, W. Nasal Colonization of Humans with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) CC398 with and without Exposure to Pigs. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, R.; Verdier, J.E.; Havelaar, A.H. Prevalence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus amongst professional meat handlers in the Netherlands, March-July 2008. Euro. Surveill. 2010, 15, 19712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuny, C.; Layer, F.; Hansen, S.; Werner, G.; Witte, W. Nasal Colonization of Humans with Occupational Exposure to Raw Meat and to Raw Meat Products with Methicillin-Susceptible and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins 2019, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rijen, M.M.; Kluytmans-van den Bergh, M.F.; Verkade, E.J.; Ten Ham, P.B.; Feingold, B.J.; Kluytmans, J.A. CAM Study Group Lifestyle-Associated Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Carriage in the Netherlands: An Exploratory Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanno, G.; Dambrosio, A.; Lorusso, V.; Samoilis, G.; Di Taranto, P.; Parisi, A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in slaughtered pigs and abattoir workers in Italy. Food Microbiol. 2015, 51, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Gomes, A.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Mama, O.M.; Sabença, C.; Sousa, M.; Silva, V.; Sousa, T.; Vieira-Pinto, M.; Igrejas, G.; et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 in Purulent Lesions of Piglets and Fattening Pigs in Portugal. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S.E.; Qi, Y.; Kaye, K.S.; Harbarth, S.; Karchmer, A.W.; Carmeli, Y. The impact of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia on patient outcomes: Mortality, length of stay, and hospital charges. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2005, 26, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, K.; Zhang, Y. Multidrug-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci in food animals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Namvar, A.E. Detection of genes involved in biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2016, 11, Doc07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, V.; Almeida, L.; Gaio, V.; Cerca, N.; Manageiro, V.; Caniça, M.; Capelo, J.L.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Biofilm Formation of Multidrug-Resistant MRSA Strains Isolated from Different Types of Human Infections. Pathogens 2021, 10, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Cuellar, E.; Tsuchiya, K.; Valle-Ríos, R.; Medina-Contreras, O. Differences in Biofilm Formation by Methicillin-Resistant and Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Diseases 2023, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Normanno, G.; Di Ciccio, P.; Pedonese, F.; Nuvoloni, R.; Parisi, A.; Santagada, G.; Colagiorgi, A.; Zanardi, E.; Ghidini, S.; et al. Biofilm Formation and Its Relationship with the Molecular Characteristics of Food-Related Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2364–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, E.A.; Picech, F.; Renna, M.S.; Baravalle, C.; Andreotti, C.S.; Russi, R.; Calvinho, L.F.; Diez, C.; Dallard, B.E. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus adhesion and biofilm-producing genes and their expression during internalization in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 183, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, J.C.; Kok, E.Y.; Vallejo, J.G.; Campbell, J.R.; Hulten, K.G.; Mason, E.O.; Kaplan, S.L. Clinical and Molecular Features of Decreased Chlorhexidine Susceptibility among Nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus Isolates at Texas Children’s Hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 60, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.M.; Ahmed, M.A. Distribution of chlorhexidine resistance genes among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: The challenge of antiseptic resistance. Germs 2022, 12, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longtin, J.; Seah, C.; Siebert, K.; McGeer, A.; Simor, A.; Longtin, Y.; Low, D.E.; Melano, R.G. Distribution of antiseptic resistance genes qacA, qacB, and smr in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Toronto, Canada, from 2005 to 2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2999–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, J.C.; Sommer, L.M.; Vallejo, J.G.; Hulten, K.G.; Kaplan, S.L. Association of qacA/B and smr Carriage with Staphylococcus aureus Survival following Exposure to Antiseptics in an Ex Vivo Venous Catheter Disinfection Model. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0333322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Vale, B.C.M.; Nogueira, A.G.; Cidral, T.A.; Lopes, M.C.S.; de Melo, M.C.N. Decreased susceptibility to chlorhexidine and distribution of qacA/B genes among coagulase-negative Staphylococcus clinical samples. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the transmission of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) during animal transport. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleist, J.F.; Bachmann, L.; Huxdorff, C.; Eger, E.; Schaufler, K.; Wedemeyer, J.; Homeier-Bachmann, T. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in wastewater from German slaughterhouses. One Health 2025, 21, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warriner, K.; Aldsworth, T.G.; Kaur, S.; Dodd, C.E.R. Cross-contamination of carcasses and equipment during pork processing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Been, M.; Lanza, V.F.; de Toro, M.; Scharringa, J.; Dohmen, W.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Tooming-Klunderud, A.; et al. Dissemination of cephalosporin resistance genes between Escherichia coli strains from farm animals and humans by specific plasmid lineages. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmithausen, R.M.; Schulze-Geisthoevel, S.V.; Stemmer, F.; El-Jade, M.; Reif, M.; Hack, S.; Meilaender, A.; Montabauer, G.; Fimmers, R.; Parčina, M.; et al. Analysis of Transmission of MRSA and ESBL-E among Pigs and Farm Personnel. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilli, E.; Vismarra, A.; Villa, Z.; Bonilauri, P.; Bacci, C. ESβL E. coli isolated in pig’s chain: Genetic analysis associated to the phenotype and biofilm synthesis evaluation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 289, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, M.; Andriani, L.; Poeta, A.; Casadio, C.; Diegoli, G.; Bonardi, S.; Conter, M.; Bacci, C. Transmission of β-lactamases in the pork food chain: A public health concern. One Health 2023, 17, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffert, S.N.; Hilty, M.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative organisms in livestock: An emerging problem for human health? Drug Resist. Updat. 2013, 16, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livermore, D.M.; Canton, R.; Gniadkowski, M.; Nordmann, P.; Rossolini, G.M.; Arlet, G.; Ayala, J.; Coque, T.M.; Kern-Zdanowicz, I.; Luzzaro, F.; et al. CTX-M: Changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 59, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00047-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E.R.; Jones, A.M.; Hawkey, P.M. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: Temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2145–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, H.; Bai, X.; Wang, D. Global spread characteristics of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases: A genomic epidemiology analysis. Drug Resist. Updat. 2024, 73, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahms, C.; Hübner, N.O.; Kossow, A.; Mellmann, A.; Dittmann, K.; Kramer, A. Occurrence of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in Livestock and Farm Workers in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, M.; Bierbaum, G.; Hammerl, J.A.; Heinemann, C.; Parcina, M.; Sib, E.; Voigt, A.; Kreyenschmidt, J. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antimicrobial residues in wastewater and process water from German pig slaughterhouses and their receiving municipal wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.N.D.C.E.; Caron, E.F.F.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Juliano, L.C.B.; Tadielo, L.E.; Melo, P.R.L.; de Oliveira, J.P.; Pantoja, J.C.F.; Martins, O.A.; Nero, L.A.; et al. Escherichia coli Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance in a Swine Slaughtering Process. Pathogens 2024, 13, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Singh, R.; Kaur, S.; Parmar, N.; Tyagi, A.; Aulakh, R.S.; Gill, J.P.S. Multidrug-Resistant Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase producing Escherichia coli in Poultry and Cattle Farms in India: Prevalence and Survey-Based Risk Factors. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 44, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, S.; Châtre, P.; François, P.; Abdullahi, I.N.; Simón, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Madec, J.-Y.; Haenni, M.; Torres, C. Unexpected role of pig nostrils in the clonal and plasmidic dissemination of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli at farm level. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 273, 116145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.T.Q.; Hounmanou, Y.M.G.; Dang, S.T.T.; Olsen, J.E.; Truong, G.T.H.; Tran, N.T.; Scheutz, F.; Dalsgaard, A. Genetic Comparison of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli from Workers and Pigs at Vietnamese Pig Farms. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ge, C. Biofilm Formation and Control of Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.T.; Chou, C.C. Class 1 Integrons and the Antiseptic Resistance Gene (qacEΔ1) in Municipal and Swine Slaughterhouse Wastewater Treatment Plants and Wastewater-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6249–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.R.; English, L.L.; Carter, P.J.; Proescholdt, T.; Lee, K.Y.; Wagner, D.D.; White, D.G. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of enterococcus species isolated from retail meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 7153–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarotto, K.; Ploy, M.C.; Dupron, F.; Giangiobbe, M.; Denis, F. Occurrence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in pork and poultry products from a cattle-rearing area of France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2354–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Alonso, C.A.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; León-Sampedro, R.; Del Campo, R.; Coque, T.M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococcus spp. of animal origin. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.I.; Ibrahem, H.M.; Hamed, D.M.; Fawzy, D.E. Human Health Risks Associated with Antimicrobial-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Poultry and Human. Alex. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 61, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Ramos, E.; Molina-González, D.; Blanco-Morán, S.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Capita, R. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and genotypic characterization of Vancomycin-Resistant enterococci in meat preparations. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, M.; Pate, M.; Kušar, D.; Dermota, U.; Avberšek, J.; Papić, B.; Zdovc, I. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes in Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis from Humans and Retail Red Meat. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 2815279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro Marques, J.; Coelho, M.; Santana, A.R.; Pinto, D.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T. Dissemination of Enterococcal Genetic Lineages: A One Health Perspective. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, B.L.; Rice, L.B. Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in enterococcus. Virulence 2012, 3, 421–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, O.; Alm, E.; Greko, C.; Bengtsson, B. The rise and fall of a vancomycin-resistant clone of Enterococcus faecium among broilers in Sweden. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 17, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddey, B.; Shaukat, W.; Tang, K.L.; Barkema, H.W. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus prevalence and its association along the food chain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Assessing the Health Burden of Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU/EEA, 2016–2020; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022.

- Leavis, H.L.; Willems, R.J.; Top, J.; Spalburg, E.; Mascini, E.M.; Fluit, A.C.; Hoepelman, A.; de Neeling, A.J.; Bonten, M.J. Epidemic and nonepidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman Prieto, A.M.; van Schaik, W.; Rogers, M.R.; Coque, T.M.; Baquero, F.; Corander, J.; Willems, R.J. Global Emergence and Dissemination of Enterococci as Nosocomial Pathogens: Attack of the Clones? Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, W.; Willems, R.J. Genome-based insights into the evolution of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, G.; Russell, A.D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Mota, J.; Boué, G.; Prévost, H.; Maillet, A.; Jaffres, E.; Maignien, T.; Arnich, N.; Sanaa, M.; Federighi, M. Environmental monitoring program to support food microbiological safety and quality in food industries: A scoping review of the research and guidelines. Food Control 2021, 130, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Fernandes, M.; Alvares, A.C.C.; Manoel, J.G.M.; Esper, L.M.R.; Kabuki, D.Y.; Kuaye, A.Y. Formation of multi-species biofilms by Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus faecalis, and Bacillus cereus isolated from ricotta processing and effectiveness of chemical sanitation procedures. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 72, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, G.; Coque, T.M.; Hammerum, A.M.; Hope, R.; Hryniewicz, W.; Johnson, A.; Klare, I.; Kristinsson, K.G.; Leclercq, R.; Lester, C.H.; et al. Emergence and spread of vancomycin resistance among enterococci in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2008, 13, 19046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerum, A. Enterococci of animal origin and their significance for public health. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wist, V.; Morach, M.; Schneeberger, M.; Cernela, N.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Zurfluh, K.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Phenotypic and Genotypic Traits of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci from Healthy Food-Producing Animals. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.; Allan, R.N.; Howlin, R.P.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Targeting microbial biofilms: Current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.Y.; Centeleghe, I. How biofilm changes our understanding of cleaning and disinfection. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2023, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napit, R.; Gurung, A.; Poudel, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Manandhar, P.; Sharma, A.N.; Raut, S.; Pradhan, S.M.; Joshi, J.; Poyet, M.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of human, animal, and environmental samples identifies potential emerging pathogens, profiles antibiotic resistance genes, and reveals horizontal gene transfer dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwirzitz, B.; Wetzels, S.U.; Dixon, E.D.; Stessl, B.; Zaiser, A.; Rabanser, I.; Thalguter, S.; Pinior, B.; Roch, F.F.; Strachan, C.; et al. The sources and transmission routes of microbial populations throughout a meat processing facility. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-A-82055-19:2000; Meat and Meat Products—Microbiological Testing—Determination of Microbiological Contamination of Surfaces of Equipment, Appliances, Rooms, Packaging, and Employees’ Hands. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. (In Polish)

- ISO 18593:2018; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Methods for Surface Sampling. (Edition 2); ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1441/2007 of 5 December 2007 Amending Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs. OJ L 322, 7.12.2007. pp. 12–29. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2007/1441/oj (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- ISO 6887-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Preparation of Test Samples, Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilutions for Microbiological Examination. Part 2: Specific Rules for the Preparation of Meat and Meat Products. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63336.html (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- PN-EN ISO 6888-1:2022-03; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species). Part 1: Method Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- ISO 16649-2:2001; Microbiology of Food and animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Beta-Glucuronidase-Positive Escherichia coli. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/29824.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 15.0. 2025. Available online: https://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumperman, P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, N.; Hase, M.; Kitta, M.; Sasatsu, M.; Deguchi, K.; Kono, M. Antiseptic susceptibility and distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 172, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignak, S.; Nakipoglu, Y.; Gurler, B. Frequency of antiseptic resistance genes in clinical staphycocci and enterococci isolates in Turkey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorland, J.; Steinum, T.; Kvitle, B.; Waage, S.; Sunde, M.; Heir, E. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4363–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Dahiya, D.K.; Khan, A.; Mathur, M.; Sharma, A. Coagulase gene polymorphism, enterotoxigenecity, biofilm production, and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine raw milk in North West India. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2017, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, H.; Knobloch, J.K.; Horstkotte, M.A.; Mack, D. Correlation of Staphylococcus aureus icaADBC genotype and biofilm expression phenotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 4595–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, L.; Paba, A.; Daga, E.; Comunian, R.; Zanetti, S.; Dupre, I. Comparison of the incidence of virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance between Enterococcus faecium strains of dairy, animal and clinical origin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 88, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Baghdayan, A.S.; Huycke, M.M.; Lindahl, G.; Gilmore, M.S. Infection-derived Enterococcus faecalis strains are enriched in esp, a gene encoding a novel surface protein. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Andrade Melo, R.; de Barros, E.M.; Loureiro, N.G.; de Melo, H.R.; Maciel, M.A.; Souza Lopes, A.C. Presence of fimH, mrkD, and irp2 virulence genes in KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Recife-PE, Brazil. Curr. Microbiol. 2014, 69, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeispour, M.; Ranjbar, R. Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genotyping of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadi, B.R.; Abebe, T.; Zhang, L.; Mihret, A.; Abebe, W.; Amogne, W. Distribution of virulence genes and phylogenetics of uropathogenic Escherichia coli among urinary tract infection patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Meng, J.; McDermott, P.F.; Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Cao, G.; Hoffmann, M.; Zhao, S. Presence of disinfectant resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from retail meats in the USA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2644–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegger, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Kearns, A.; Pichon, B.; Holmes, M.A.; Edwards, G.; Laurent, F.; Teale, C.; Skov, R.; Larsen, A.R. Rapid detection, differentiation and typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harbouring either mecA or the new mecA homologue mecA(LGA251). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutka-Malen, S.; Evers, S.; Courvalin, P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant Enterococci by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanella, R.C.; Brandileone, M.C.; Bokermann, S.; Almeida, S.C.; Valdetaro, F.; Vitório, F.; Moreira, M.d.F.; Villins, M.; Salomão, R.; Pignatari, A.C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of VanA Enterococcus isolated during the first nosocomial outbreak in Brazil. Microb. Drug Resist. 2003, 9, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundran, R.S.; Cardenio, P.A.; Villanueva, M.A.; Sison, F.B.; Benigno, C.C.; Kreausukon, K.; Pichpol, D.; Punyapornwithaya, V. Prevalence and distribution of blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEM genes in extended- spectrum β- lactamase- producing E. coli isolates from broiler farms in the Philippines. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Butchers, n = 30 | Non-Production Workers, n = 7 |

|---|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) | 42.4 (12.2) | 37.1 (7.8) |

| Female (%) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (71.4) |

| Use of antibiotics (within 6 months) | 2 (6.7%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Living on an agricultural or livestock farm | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Length of employment in current position (years) | 8.3 (7.1) | 7.7 (9.4) |

| Sampling Sources (No. of Samples) | ESBL-E. coli | MRSA | VRE-E. faecium | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Slaughter and evisceration sections | ||||||

| Bioaerosol (n = 4) | 3 | 75.0% | 1 | 25.0% | 1 | 25.0% |

| Conveyors (n = 8) | 2 | 25.0% | 2 | 25.0% | 3 | 37.5% |

| Hooks and trays (n = 9) | 6 | 66.7% | 3 | 33.3% | 2 | 22.2% |

| Saws (n = 8) | 1 | 12.5% | 1 | 12.5% | 2 | 25.0% |

| Floors (n = 8) | 3 | 37.5% | 3 | 37.5% | 4 | 50.0% |

| Meat cutting sections | ||||||

| Bioaerosol (n = 6) | 3 | 50.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Knives and cleavers (n = 10) | 1 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 10.0% |

| Work tops (n = 10) | 2 | 20.0% | 1 | 10.0% | 2 | 20.0% |

| Containers | 3 | 37.5% | 3 | 37.5% | 2 | 25.0% |

| Floors | 1 | 12.5% | 2 | 25.0% | 2 | 25.0% |

| Meat processing sections | ||||||

| Bioaerosol (n = 10) | 3 | 30.0% | 1 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Grinders (n = 9) | 3 | 33.3% | 1 | 11.1% | 2 | 22.2% |

| Stuffer machines (n = 8) | 1 | 12.5% | 3 | 37.5% | 2 | 25.0% |

| Containers (n = 9) | 2 | 22.2% | 2 | 22.2% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Work tops (n = 9) | 1 | 11.1% | 1 | 11.1% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Floors (n = 9) | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 22.2% | 4 | 44.4% |

| Warehouse/retail space | ||||||

| Bioaerosol (n = 6) | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Work tops (n = 8) | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 12.5% |

| Butcher scales (n = 7) | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Floors (n = 7) | 1 | 14.3% | 1 | 14.3% | 1 | 14.3% |

| Meat | ||||||

| Carcasses (n = 15) | 8 | 53.3% | 7 | 46.7% | 5 | 33.3% |

| Ready-to-eat product (n = 18) | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hands swabs | ||||||

| Butchers (n = 30) | 6 | 20.0% | 1 | 3.3% | 5 | 16.7% |

| Non-production workers (n = 7) | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 14.3% | 1 | 14.3% |

| Nasal swabs | ||||||

| Butchers | 3 | 10.0% | 1 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Non-production workers | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Sampling Sources (No. of Samples) | Non- ESBL-E. coli n (%) | ESBL-E. coli n (%) | MSSA n (%) | MRSA n (%) | VSE- E. faecium n (%) | VRE- E. faecium n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaerosols (n = 26) | 12 (57%) | 9 (43%) | 13 (87%) | 2 (13%) | 13 (93%) | 1 (7%) |

| Equipment and surfaces (n = 135) | 60 (68%) | 28 (32%) | 73 (74%) | 25 (26%) | 43 (61%) | 28 (39%) |

| Pork carcasses (n = 15) | 4 (33%) | 8 (67%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (58%) | 5 (42%) |

| Ready-to-eat meat products (n = 18) | 6 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hand swabs (n = 37) | 28 (82%) | 6 (18%) | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) | 8 (57%) | 6 (43%) |

| Nasal swabs (n = 37) | 15 (79%) | 4 (21%) | 5 (83%) | 1 (17%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gene | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) | Product Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| qacA/B | GCAGAAAGTGCAGAGTTCG CCAGTCCAATCATGCCTG | 361 | [120,121] |

| smr | GCCATAAGTACTGAAGTTATTGGA GACTACGGTTGTTAAGACTAAACCT | 195 | [120,121] |

| qacG | CAA CAG AAA TAA TCG GAA CT TAC ATT TAA GAG CAC TAC A | 275 | [121,122] |

| fnbpB | TCTGCGTTATGAGGATTT ACAGTAGAGGAAAGTGGG | 452 | [123] |

| fnbpA | TCCGCCGAACAACATACC TCAAGCACAAGGACCAAT | 952 | [123] |

| cna | CGATAACATCTGGGAATAAA ATAGTCTCCACTAGGCAACG | 716 | [123] |

| icaBC | GCCTATCCTTATGGCTTGA TGGAATCCGTCCCATCTC | 182 | [123] |

| icaA | ACACTTGCTGGCGCAGTCAA TCTGGAACCAACATCCAACA | 188 | [124] |

| gelE | AGTTCATGTCTATTTTCTTCAC CTTCATTATTTACACGTTTG | 402 | [125] |

| efaA | CGTGAGAAAGAAATGGAGGA CTACTAACACGTCCACGAATG | 499 | [125] |

| esp | TTACCAAGATGGTTCTGTAGGCAC CCAAGTATACTTAGCATCTTTTGG | 913 | [126] |

| mrkD | CCACCAACTATTCCCTCGAA ATGGAACCCACATCGACATT | 228 | [127] |

| fimH | GAGAAGAGGTTTGATTTAACTTATTG AGAGCCGCTGTAGAACTGAGG | 559 | [128] |

| sfa/focDE | CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA | 410 | [129] |

| ydgF | TAGGTCTGGCTATTGCTACGG GGTTCACCTCCAGTTCAGGT | 330 | [130] |

| qacEΔ1 | AATCCATCCCTGTCGGTGTT CGCAGCGACTTCCACGATGGGGAT | 175 | [130] |

| emrE | TATTTATCTTGGTGGTGCAATAC ACAATACCGACTCCTGACCAG | 195 | [130] |

| mdfA | GCATTGATTGGGTTCCTAC CGCGGTGATCTTGATACA | 284 | [130] |

| mecA | TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG | 162 | [131] |

| mecC (mecALGA251) | GAAAAAAAGGCTTAGAACGCCTC GAAGATCTTTTCCGTTTTCAGC | 138 | [131] |

| vanA | GGGAAAACGACAATTGC GTACAATGCGGCCGTTA | 732 | [132] |

| vanB | ACCTACCCTGTCTTTGTGAA AATGTCTGCTGGAACGATA | 300 | [133] |

| blaTEM | TTGGGTGCACGAGTGGGTTA TAATTGTTGCCGGGAAGCTA | 506 | [134] |

| blaSHV | TCGGGCCGCGTAGGCATGAT AGCAGGGCGACAATCCCGCG | 628 | [134] |

| blaCTX-M | ATGTGCAGYACCAGTAARGTKATGGC TGGGTRAARTARGTSACCAGAAYSAGCGG | 592 | [134] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Cyprowski, M.; Gołofit-Szymczak, M.; Górny, R.L. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli, and Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium in the Production Environment and Among Workers in Low-Capacity Slaughterhouses in Poland. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121200

Ławniczek-Wałczyk A, Cyprowski M, Gołofit-Szymczak M, Górny RL. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli, and Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium in the Production Environment and Among Workers in Low-Capacity Slaughterhouses in Poland. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121200

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁawniczek-Wałczyk, Anna, Marcin Cyprowski, Małgorzata Gołofit-Szymczak, and Rafał L. Górny. 2025. "Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli, and Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium in the Production Environment and Among Workers in Low-Capacity Slaughterhouses in Poland" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121200

APA StyleŁawniczek-Wałczyk, A., Cyprowski, M., Gołofit-Szymczak, M., & Górny, R. L. (2025). Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus, Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli, and Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium in the Production Environment and Among Workers in Low-Capacity Slaughterhouses in Poland. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121200