1. Introduction

The existing literature describes digital transformation (DT) in higher education as a coordinated change effort involving organizational arrangements (structure, strategy, and supporting systems), human resources and their culture, and technology that enables new educational and operational models [

1]. European evidence shows that strategic, institution-wide approaches to digitally enabled learning and teaching have become the norm—but with considerable variation in their implementation [

2]. A central unresolved question is how digital maturity (DM) is translated into organizational transformation, as perceived by faculty, students, and other relevant HEI stakeholders.

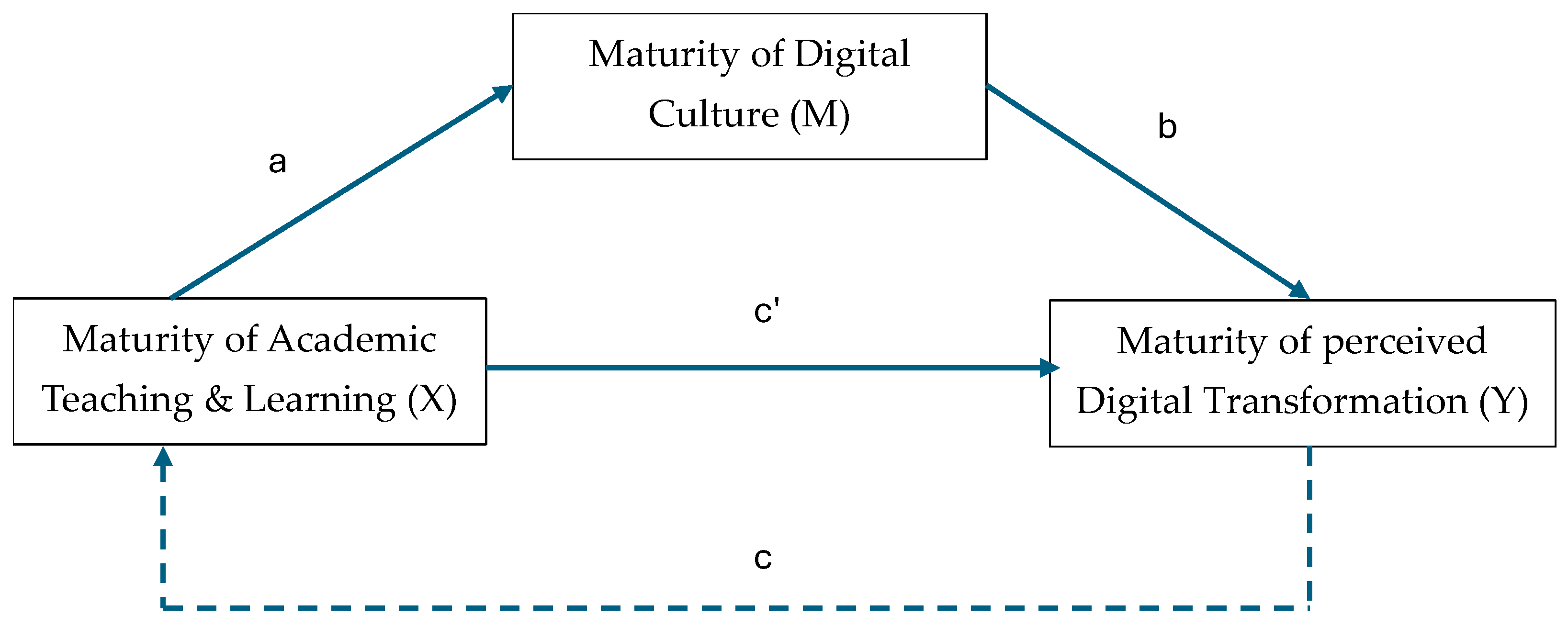

This study continues previous research on the associations among different dimensions of digital maturity and the digital transformation of B&H and Croatian HEIs by testing digital culture as a mediating mechanism. We argue that the associations between Academic Teaching & Learning digital maturity and Digital Transformation are mediated by Digital Culture, which emphasizes experimentation, collaboration, and data-driven decision-making. Our approach is based on capability-based approaches to transformational change, which focus on the continuous reconfiguration of organizational resources [

3] and on the role of human resources and their knowledge in this process [

4].

Unfortunately, the B&H and Croatian policy contexts are characterized by a lack of managerial and organizational capacity [

5], which could leverage the existing digital infrastructure to implement digital transformation [

6]. This conclusion is supported by the empirical results of a prior study [

7], which demonstrate an association between the digital maturity of Academic Teaching & Learning and Digital Resources and Infrastructure, and the perceived level of Digital Transformation.

Therefore, there is a need to theoretically model the associations between Academic Teaching & Learning (the most significant dimension of DM) and DT in higher education, with a preliminary empirical test of the mediating role of digital culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) and Croatia. This study represents a separate theoretical and empirical contribution, as the initial study [

7] focuses on the static evaluation of the contribution of digital maturity dimensions to digital transformation. On the other hand, this paper considers the dynamics of the process, using the DM of Academic Teaching & Learning as a previously recognized, statistically significant DT predictor and a directly related indicator of the primary HEI mission.

It should be noted that this study employs a cross-sectional research design, which does not infer causal relationships, but rather illustrates current associations among the constructs of Academic Teaching & Learning, Digital Culture, and Digital Transformation maturity. All results described in this paper should be interpreted as indicative and associative patterns, rather than evidence of causal relationships at different time periods.

The study is structured as follows: after the introduction, we present the theoretical background (the overview of extant research) in the second section. In the third section of the paper, we describe our methodology and research instrument. The fourth section presents the empirical results, which are further discussed in the fifth section. The sixth section presents a short conclusion.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper is a follow-up analysis to our previously published cross-sectional study of digital maturity and perceived digital transformation in Western Balkan HEIs [

7]. In this paper, we move beyond a simple analysis of bivariate associations to a more detailed analysis by testing whether digital culture functions as an organizational mediator that influences the dynamics of association between digital maturity of Academic Teaching & Learning and the perceived scope and success of Digital Transformation in higher education. Methodologically, we employ the same validated short instrument and dataset structure to ensure comparability, but utilize bootstrapped mediation models (Hayes PROCESS Model 4) to examine the association between maturity and digital transformation statistically.

The present study uses a comparable survey frame, setting, and recruitment procedures as in the earlier article: an online questionnaire was administered via LimeSurvey (hosted by University Computing Center SRCE, located in Zagreb, Croatia) to students, academic staff, and administrative staff at four public HEIs in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Data collection was conducted in two waves. In the first wave, data were collected at the University of Applied Sciences “Marko Marulić” (Knin, Croatia), University North (Varaždin, Croatia), and the Faculty of Economics at the University of Mostar (Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina). The first wave of data collection was conducted from March to April 2025. HEI stakeholders were identified through public directories, institutional Web pages (faculty and administrative staff), or by invitation via Moodle Learning Management System (LMS) links. Participation was voluntary, and all participants were guaranteed complete anonymity and statistical reporting of their responses. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the start of the electronic survey. From 137 valid questionnaires reported in a previous study [

7], the analytic sample for mediation consists of 134 cases after listwise deletion of the missing data for the variables used in the PROCESS model.

In the second wave of data collection, conducted in November 2025, we used the same approach to extend our analysis to the University of Banja Luka, the largest state-owned university in the entity of the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since the initial data collection was restricted to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (one of the two major entities in B&H), this represented a significant limitation. In the new wave, we collected an additional 65 questionnaires. After eliminating empty responses, we added 49 additional questionnaires from the University of Banja Luka to the existing dataset, bringing the final dataset to 186 respondents.

Since some questionnaires were partially completed, we used the maximum number of cases available for each analysis rather than excluding all incomplete responses. Consequently, the sample size (N) varies slightly across analyses and is reported for each table and model.

The sampling approach was convenience-based, and we acknowledge its limited representativeness of the entire HEI stakeholder population in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. On the other hand, our final sample includes multiple stakeholder groups and four institution types, which provide variation in digital maturity. One institution is a regional leader (benchmark) in DM and DT, while other institutions represent regionally representative HEIs at the national level. In Croatia, we include a major regional university (University North) and a small regional university of applied sciences in Knin to ensure coverage of a diverse group of HEIs.

In both data collection waves, we employed a short form of the Digital Maturity for Higher Education Institutions (DMFHEI) instrument, developed within the Higher Decision Research Project framework. The short version of the DMFHEI instrument was developed and validated in an earlier paper, preserving coverage of DM dimensions while reducing respondent burden [

7]. The items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The whole instrument is available in the

Supplementary Materials of the prior publication [

7], while we include the open research data in the

Supplementary Materials of this manuscript.

For the statistical analyses, we formed the following composite variables (means of their respective items):

Teaching and Learning maturity—the extent to which an HEI adopts digital learning tools, pedagogies, and other relevant innovations in the teaching and learning processes;

Maturity of digital (digitally oriented) culture—norms and values among HEI stakeholders, supporting digital literacy, organizational innovation, and experimentation—is based on the use of electronic tools and platforms and the digitalization of organizational processes;

Perceived scope and success of digital transformation—the level of stakeholders’ perceptions concerning the overall digital transformation of a HEI.

Internal consistency for all indicators was acceptable, with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.861 for Teaching and Learning, 0.846 for Digital Culture, and 0.912 for Digital Transformation maturity. Additionally, we have examined the distributions of all constructs used in the empirical research (see

Table 1).

Shapiro–Wilk tests for composite variables indicate that our constructs are not normally distributed, as the p-values are all below 0.05. Nevertheless, we rely on Hayes’s bootstrap procedure to estimate indirect effects. Since the bootstrapping approach is robust to the assumption of normality, departures from normality are appropriate for the planned statistical analysis.

Our final sample consisted of 75.8% female and 24.2% male participants, which aligns with the gender imbalance in extant social science research [

16] and may be linked to gender differences in cooperative orientation. However, this is a significant limitation of this study.

Out of 186 responses included in the final dataset, 135 participants (72.6%) were students, 24 (12.9%) were university instructors (professors with academic titles), 12 (6.5%) were administrative staff, and only 4 (2.2%) were teaching and research assistants. Eleven respondents (5.9%) opted out of answering, as all demographic information was provided voluntarily. The distribution of responses across students, faculty, and administrative staff closely mirrors the actual structure of university stakeholders in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Unfortunately, junior staff (teaching and research assistants) are under-represented. Due to limited funding, the number of junior staff at universities in both countries has been steadily decreasing, and their workload is high, especially given the requirement to complete their PhD degrees within the duration of their limited contracts. We believe these are significant reasons for their low response to the multiple requests to participate in this survey.

We used IBM SPSS 28 with the Hayes PROCESS macro v4.3. All mediation analyses were based on bootstrapping estimates of the overall indirect effect, without resorting to the deprecated analysis of individual indirect paths. All effects were interpreted using the traditional criterion of a 95% confidence interval (CI) that did not include zero, following Hayes’ methodological recommendations [

17]. For additional transparency, we also report the total effect (c), direct effect (c′), and R

2 for the outcome model.

4. Results

First, we examined the statistical assumptions and conducted diagnostic checks for mediation. As already indicated, our analytical strategy is mainly independent of departures from normality assumptions. However, we still need to analyze the effects of potential heteroskedasticity among similarly operationalized measures and demonstrate the validity of the constructs and the model by examining the common method bias.

We proceeded by examining simple linear correlations among the primary constructs (see

Table 2). Although all correlations are strong and statistically significant, none exceed 0.8.

Potential common method variance (CMV) was evaluated using Harman’s single-factor analysis, in which all survey items were subjected to PCA (Principal Component Analysis), yielding a single factor [

18]. In our case, two components were extracted, each with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0. The first factor accounted for 55.25% of the total variance, and the second factor explained an additional 8.29%. Although the first factor accounts for more than 50% of the variance, the existence of a second factor suggests that CMV is unlikely, although some bias remains possible. Therefore, the interpretation of empirical results needs to be cautious.

We checked the statistical assumptions and estimated another simple mediation model (Hayes PROCESS Model 4) using 10,000 bootstrap samples and confidence intervals, with the same predictors and DV, and also including the dummy variables as institutional covariates.

After completing the data collection, we estimated the mediation model using Hayes’ PROCESS Model 4 with 10,000 bootstrap resamples and percentile 95% confidence intervals. The bootstrapped indirect effect of Teaching & Learning maturity on perceived DT via Digital Culture was statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.232, Boot SE = 0.055, percentile CI [0.129, 0.346]). Digital Culture accounted for a significant portion of the association between Academic Teaching and Learning maturity and the Digital Transformation (DT) maturity.

The direct effect of Teaching & Learning digital maturity on perceived DT, controlling for Digital Culture, remained positive and significant (b = 0.428, SE = 0.063, 95% CI [0.303, 0.553]), consistent with partial mediation. Adding Digital Culture increased explained variance in perceived DT from R

2 = 0.521 (direct association only) to R

2 = 0.583 (model including both Teaching & Learning digital maturity and Digital Culture), with the ΔR

2 ≈ 0.063. In the estimated model, the mediated association is approximately 35%, indicating that roughly one-third of the analyzed association is transmitted via Digital Culture (see

Table 3).

We also considered estimating a multilevel mediation analysis, which would be very useful if we had a large number of higher-education institutions (HEIs) in a sample to reliably estimate the components of variance between institutions [

19]. However, due to the preliminary nature of this study and its cross-sectional design, we collected data from only four HEIs, which could lead to unstable multilevel path estimates and unreliable standard errors [

20]. Therefore, we use a conservative approach to ensure the robustness of the reported results by including three dummy covariates. Each represents one of three institutions, i.e., fixed effects for three HEIs, with the University of Mostar (Sveučilište u Mostaru—SUM) serving as the base category.

In the extended model, the maturity of Academic Teaching and Learning (

b = 0.37,

p < 0.001) and Digital Culture (

b = 0.38,

p < 0.001) were positively associated with the perceived Digital Transformation, controlling for institutional dummy variables (see

Table 4). The bootstrap estimate of the indirect effect of digital maturity was statistically different from zero (

b = 0.25, BootSE = 0.06, 95% percentile CI [0.16, 0.37]), being consistent with the hypothesized mediating role of digital culture. The direct effect was also significant (

b = 0.37, 95% CI [0.24, 0.50]). Overall, there is a significant indirect association through digital culture as a mediator, which is robust to mean-level differences and modeled using institutional dummy covariates.

5. Discussion

Our findings are consistent with the mediating role of digital culture in linking the maturity of Academic Teaching & Learning to Digital Transformation. This finding is supported by the sociotechnical view of information systems and their organizational effects [

1,

2]. In addition, our results align with the dynamic-capability view, which emphasizes the role of capabilities in creating and reconfiguring routines that enable organizations to align with their external environment [

3].

Academic Teaching and Learning maturity is significantly associated with Digital Culture, which, in turn, is associated with perceived digital transformation. From a theoretical viewpoint, this finding is compatible with the existing literature on pedagogical innovation, which suggests that it is highly culturally sensitive and dependent on faculty members’ psychological safety [

11,

12]. Additional theoretical mechanisms include the utilization of HEI absorptive capacity to develop new routines and transform existing practices [

13,

14] and the application of knowledge management tools and communities to drive the adoption of digital tools and digital innovation [

15].

As indicated by prior research [

7], technological infrastructure and resources represent a foundation for digitally mature Academic Teaching & Learning, while human values, norms, and risk tolerance, constituting the Digital Culture, appear to shape how the digital infrastructure and resources are used and how they contribute to perceived transformational change [

21]. Critical reviews of technology-enhanced learning also indicate that a culture of collaboration and inquiry is necessary for effective technology-enhanced teaching and learning [

22], which aligns with our initial expectations, as formulated by the working hypothesis.

Consistent with the working hypothesis that digital culture mediates the association between academic teaching and substantive learning, we observe a significant indirect effect of teaching and learning through culture.

Although our hypothesis has been confirmed, there are alternative theoretical explanations and multiple limitations of this study that need to be acknowledged. Since all constructs were measured using self-reported perceptions, the issues of common-method bias and social desirability bias cannot be entirely ruled out. The results of Harman’s single-factor test also require careful interpretation and consideration from multiple viewpoints.

One possible interpretation is from a policy perspective, considering the EU Digital Education Action Plan 2021–2027 [

23], which focuses on digital education and calls for strengthening the resource base and capabilities for digital transformation. Our positioning of Digital Culture as a relevant resource development factor and a source of dynamic capabilities suggests that constructing and funding digital infrastructure does not guarantee achieving transformational change. We believe that cultural interventions, leadership development, and staff capacity-building should complement digital infrastructure and resources to enhance overall effectiveness. These culture-focused interventions are even more important in resource-limited environments, where Digital Culture can serve as a lever for limited infrastructure investment.

In addition, the cultural lever aligns with a theoretical perspective, as outlined in institutional theory, which interprets DT as a result of pressures to conform to the dominant paradigm of “Western-style” modernity in higher education [

24]. This view is especially relevant for business schools and other university departments seeking international visibility, recognition, and accreditation [

25]. Thus, our view of Digital Culture can also be interpreted as aligning B&H and Croatian HEIs with EU and national policy expectations for the modernization and digitalization of higher education [

26].

It can be argued that our research results do not represent a novel contribution from sociotechnical and systemic perspectives. However, traditional research into sociotechnical systems has very rarely addressed the specific context of public sector HEIs, the resource-constrained environments of post-transition countries, or the issues of social dominance and EU conditionality [

27] posed by institutional theory. These theoretical issues have recently emerged as central to the discussion of higher education policy in post-transitional, peripheral European countries [

28] and should be addressed in the consideration of digital reforms and the transformation of HEIs.

Still, our analysis has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Further analyses of DT in higher education should triangulate self-reported and perceptual data with objective indicators, such as Learning Management System usage logs, data from external audits and accreditations, and other ‘hard data’. Additional qualitative evidence from stakeholder interviews or focus groups could also be included in future research designs to provide richer data on HEI practices, technology adoption, organizational culture, and their effects on transformational change.

As already mentioned, this study employs a cross-sectional research design, providing robust information on current associations among the research constructs without inferring causal direction. Future research should therefore examine reverse causality and reciprocal relationships between Digital Culture and Digital Transformation. This might be especially plausible for HEIs, which have already achieved high DT levels. Their existing success could be shaping their organizational culture and, in turn, influencing the development of Digital Maturity.

To move beyond establishing associations and analyzing causal relationships, future research should employ longitudinal designs, preferably with multiple data collection waves timed to enable theorizing about causal effects. For instance, the first wave could focus on measuring digital maturity, followed by measuring culture (as a mediating mechanism), and conclude by collecting data on the outcomes of transformational change (at the end of the longitudinal data collection).

Another significant limitation of the current research is the generalizability of the results, which is acceptable at this point, as the study aims to provide preliminary insight into the role of Digital Culture in HEIs’ transformational change. Although we partially controlled for institutional effects by using dummy variables, unobserved institutional factors may also be at play. These limitations could be addressed through a more complex sampling strategy across the Western Balkans to achieve greater regional generalizability of research results.

A mix of public and private HEIs, both research-oriented (universities and research-oriented independent institutions) and applied science schools and departments, should be included in future research efforts. In this way, institutional diversity will be better captured, ensuring variability across different levels of digital maturity and transformation. In addition, future sampling strategies need to ensure geographical diversity and a hierarchical data structure that extends from the class to the institutional and national levels of analysis.

Such a sampling strategy should also ensure that future research accurately assesses the potential digital divides at regional and national levels, as multilevel research designs enable researchers to analyze the distribution of strategic resources (antecedents of DT), digital culture, and DT effects across different social groups and types of HEIs.

Our results are consistent with interpreting organizational culture as a theoretically relevant mechanism through which higher digital maturity in Academic Teaching & Learning is associated with a higher perceived level of digital transformation. B&H and Croatian contexts make our propositions relevant from a practical viewpoint as well. In resource-constrained environments, culture can foster peer learning and interdepartmental collaboration, ultimately leading to social visibility and recognition of investments in digital tools and platforms. In this way, the development of digital infrastructure is positioned as a credible contribution to society, which may reinforce digital culture and its acceptance within the higher education sector, contributing to the development of ‘virtuous circle’ patterns.

From a theoretical standpoint, our results are relevant to dynamic capability theory in strategic management and its application in HEIs. Our study (re)positions Digital Culture maturity from a generic supporting factor toward a source of HEI dynamic capabilities. Teece’s original theorizing can be described as sensing an opportunity, committing to and allocating the strategic resource, and continuously (re)configuring the resource base and organizational routines to achieve new capabilities [

3].

In this context, digital culture serves as a “glue” for (re)combining teaching tools and approaches with the supporting digital platforms, instead of a passive supporting element. In addition, digital culture enables faculty and administrative staff to amplify the effects of limited digital resources, which is especially significant in environments with a scarce resource base. Thus, cultural capabilities may channel efforts toward achieving digital transformation (DT), which extends our prior work on the relevance of the resource base and its direct influence on DT [

7].

Our conceptualization of HEI organizational culture can be linked to HEI entrepreneurial orientation (EO), which can serve as a lever for implementing cultural interventions to support digital transformation. Namely, the culture of an academic institution can be transformed by introducing innovation, proactiveness, and a willingness to take calculated risks, implied by the introduction of EO [

29]. Our existing results can be amplified through the implementation of experiential teaching methods, such as business plan competitions, problem- and project-based learning, and other approaches that foster an entrepreneurial mindset, which can be coupled with digital culture to support HEI innovation.