1. Introduction

In Gujarati folklore, the term “Jogaṇī” or “Jogṇī” has typically denoted a female ghost or spirit often associated with cholera, among other ailments. In this way, the term follows its obvious homology with the Sanskrit “yoginīs”, minor female divinities thought to serve collectively as Durgā’s entourage. While Gujarat has no famous yoginī temples to speak of in this pan-Indian idiom, a singular Jogaṇī has often functioned on her own like a goddess, and so small shrines (or

derīs) dedicated to her abound in villages, fields and roadsides throughout the region. At these sites, the singular Jogaṇī appears to have been portrayed in aniconic form and worshipped with meat offerings, liquor oblations and possession-like trance states overseen by “

bhuvās”, ritual preceptors customarily tied to non-elite groups. Today “Jogaṇī” is still an operative word in Gujarati religion; now, however, there are an increasing number of prominent shrines and temples to Jogaṇī Mātā in major cities where she is worshipped as a bona fide Great Goddess. In these new spaces, Jogaṇī Mātā has moved toward what worshippers commonly describe as

sāttvik (“virtuous” or “pure”) rituals, completely separated from the

tāmasik (“dark” or “ignorant”) non-vegetarian and alcoholic rites. As with other goddesses bearing the title “Mātā” or “Mā” (each of which denotes an honorific form of “mother”) who have undergone similar changes as they move beyond their traditional low-caste and village contexts, Jogaṇī Mātā has also taken on a new and distinct iconography (see

Figure 1) beyond the simple stones, trees or

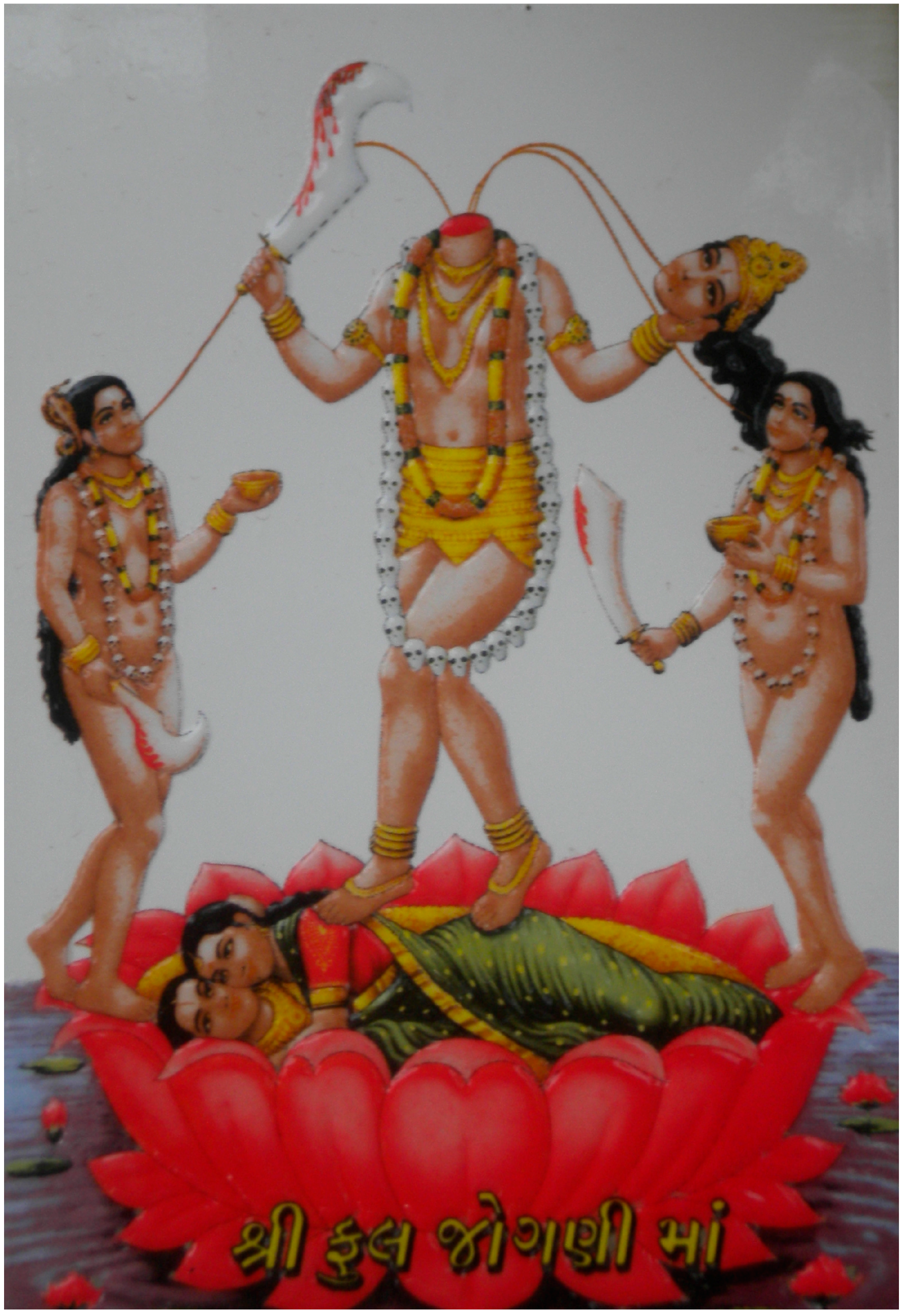

triśūls that formerly signified her sites. Yet while sweetening and sanitizing efforts have seen virtually all the Gujarati Mātās adopt lithographs depicting them as smiling young women on idiosyncratic animal mounts—Bahucarā Mātā a rooster, Khoḍīyār Mātā a crocodile, and Melaḍī Mātā a goat—following after the pan-Indian style, Jogaṇī’s iconography stands in sharp contrast. Jogaṇī is a headless female, one of her hands carrying the scimitar with which she has self-decapitated, another bearing her own head. She is naked save for a garland of skulls, and stands atop the copulating pair of Kāma and Rati while her two female attendants drink the blood spouting from her neck. This is the iconography of the tantric Mahāvidyā

1 Chinnamastā, “she who has cut off her own head.”

This representation would seem to mark Jogaṇī Mātā as one of the few examples of a regionalized Chinnamastā in contemporary India, comparable with those found at Cintapūrṇī in Himachal Pradesh (

Benard 1994, p. 145) and Rajrappa in Jharkhand (

Mahalakshmi 2014;

Singh 2010). Jogaṇī Mātā’s history, however, is not so easily elucidated. The phonological similarity between her name and “yoginī” opens up multifarious Sanskritic and folkloric connections that have no doubt influenced the goddess throughout her development. Folk elements are especially crucial, chiefly the Gujarati notion of “Jogaṇī” in the singular,

2 which marked an entity that was almost as much a ghost as she was a goddess, and seems to be at the core of the present-day Jogaṇī Mātā. In addition, Jogaṇī’s more recent assumption of the “Mātā” mantle marks her as one among a series of divinities in flux, as many of the Mātās such as those mentioned above have been Sanskritized and gentrified for an upwardly mobile urban audience, particularly following the liberalization of India’s economy in the early 1990s.

3While Jogaṇī Mātā’s background may be multifaceted, her Chinnamastā imagery and her Yoginī-homonymous name suggest that she has some undeniably tantric aspects. These tantric resonances do not appear to clash with the sensibilities of her expanding devotional base, as Jogaṇī’s temples attract an increasingly middle-class, mainstream audience, who readily consume her images and seek the benefits of her yantra and mantra. And yet despite the presence of these tantric accoutrements, Jogaṇī officiants and devotees alike rarely acknowledge her ties with tantra—in fact, they often de-emphasize or deny them. Of course, following Douglas Renfrew Brooks’ proviso to his polythetic definition of what constitutes tantra, any given text or tradition need not explicitly refer to itself as tantric to be considered tantric (

Brooks 1990, p. 53). With this in mind, I take this unrecognized tantra at contemporary urban Jogaṇī Mātā temples as my point of departure.

This essay attempts to understand not only why Jogaṇī’s tantric elements are so often downplayed, but more importantly how tantra functions in conjunction with her ongoing sweetening for a middle-class audience. I will begin by sorting through the plurality of historical, iconographic and popular literary associations Jogaṇī Mātā has accumulated on account of her links with both Chinnamastā and the yoginī(s). In the process, I hope to establish the presence in the past of a grammatically singular Jogaṇī from which the contemporary Jogaṇī Mātā evolved. From here I will move into ethnographic data collected in urban Gujarat in 2014 and 2015. We first visit a pair of Jogaṇī sites that are representative of the abovementioned tantric de-emphasis, and then a third that provides a critical exception to this trend, wholeheartedly accepting Jogaṇī as tantric. Reading all of these Jogaṇī sites through the insights of a self-identifying tāntrika from this outlying temple, I argue that they are united by their acceptance of tantra insofar as it situates the goddess within a Sanskritic and Brahmanically-amenable form of religious expression. That is, each site has been able to realize, tacitly or overtly, a positive, sāttvik tantrism that contrasts malevolent, “black” tantra, their enduring appeal attributable to the immediacy with which the “white” tantra of Jogaṇī Mā solves worldly problems. This being the case, I contend that these temples, even the ones that downplay the tantric components, actually speak to how prevalent tantra has become in Gujarat, in that it can operate unacknowledged and unproblematically in a fairly conventional context. This speaks to the cachet tantra wields within the expanding Gujarati urban middle-class, to the extent that it may even be able play a role in the sweetening or sanitization of Mātās like Jogaṇī. All three temples illustrate how tantra, as a sāttvik, Sanskritic power, can aid in an ongoing effort amongst members of relatively non-elite groups (among them Rabaris, Patels and Barots) to cultivate and perform perceived hallmarks of high status such that their social rank can parallel their desired—or, in some cases, actualized—economic ascendancy.

2. “Sweetening” Goddesses for Upwardly Mobile Sensibilities

Before tracing Jogaṇī’s background, it is first necessary to address in greater depth the patterns of change that often take place relating to rituals, theologies and iconographies of some South Asian deities—more often than not goddesses—so as to render them agreeable to upper-caste or upwardly-mobile sensibilities. While this phenomenon is often glossed as “sweetening” or “sanitizing”, terms I have employed above, it more accurately involves a complex of interwoven processes encompassing religious and economic factors. For that reason, scholars working in South Asia have proposed a number of theoretical apparatuses in an attempt to understand these sorts of changes.

The broadest of these theories is M.N. Srinivas’ notion of Sanskritization, referring to a process by which lower castes incorporate the customs, rituals and beliefs of ostensibly more refined groups such as the Brahmans or—as was often the case in Gujarat—the Jains (

Srinivas 2002, p. 200).

4 A closely related and slightly more historically contextualized theory of upward mobility is that of Vaiṣṇavization, a process in which communities or caste groups gradually adopt the iconography, mythology or rituals of Viṣṇu/Kṛṣṇa and his consort Lakṣmī. This pattern of change champions values of “dignity” and “self-limitation”, and encompasses a preference for the pan-Indic, Sanskritic, and Brahmanical over the local, vernacular, and folk.

5 Movements from local to pan-Indian and folk to Brahmanical can also be attributed to what Cynthia Humes has called “universalization” (

Hume 1996, p. 69). Based on fieldwork at the Vindhyachal pilgrimage site in Uttar Pradesh, Humes observed how the patron goddess Vindhyavāsini evolved from a highly localized tribal deity into a singular, transcendent

Ādiśakti in an Advaitic

6 mode as Vindhyachal began drawing a broader, more cosmopolitan audience (

Hume 1996, p. 74). With universalization, as with Sanskritization and Vaiṣṇavization, the emergent ethos almost always necessitates vegetarianism, abstinence from alcohol, and the spurning of other non-elite ritual expressions such as spirit possession.

Taking socioeconomic factors into account, particularly the rise of the middle-class after the liberalization of India’s economy in the early 1990s, it has become fashionable to talk about “gentrification of the goddess” (

Waghorne 2004;

Harman 2004). As Indian middle-classness

7 has come to be defined by ownership of luxury commodities,

8 as well as more intangible forms of symbolic capital such as education and cosmopolitanism,

9 these and other attendant sensibilities have had noticeable effects upon religion. Once again, this informs the elimination of animal sacrifices and possession states at religious sites, which has almost gone without saying at urban and suburban temples to Māriyammaṉ and Śītalā Mātā, small pox goddesses of South and North India, respectively (

Harman 2004, p. 11;

Ferrari 2015, p. 98). However, gentrification also involves the physical transformation of worship spaces, and so many of Māriyammaṉ’s compact shrines have in the past decades given way to elaborate urban complexes featuring ornate

maṇḍapas and

gōpuras, hallmarks of “proper” south Indian Brahmanic temple construction (

Waghorne 2004, p. 132). Meanwhile, elements of religious expression therein have been subject to a “cleaning up and ordering”, accommodating middle-class inclinations toward tidiness, prosperity, comfort, community involvement, and some degree of democratic inclusiveness (

Waghorne 2004, p. 131).

Other commentators have opted for more generalized descriptions of goddess-related reconfigurations. Starting with the traditional Indian distinction between

saumya (“benign” or “gentle”) and

ugra (“ferocious” or “wild”) goddesses,

10 Annette Wilke has proposed that examples of the latter such as Akhilāṇḍeśvari and Kāmākṣī often undergo a “taming” by way of marriage (

Wilke 1996, p. 126). Comparably, the disheveled goddess Dhūmāvatī, who like her fellow Mahāvidyā Chinnamastā has been predominantly connected to the tantric context and identified by her inauspicious traits, has from the late nineteenth century onward been reconfigured as world-maintaining and well-wishing (

Zeiler 2012, p. 181). Even though

pūjārīs at Dhūmāvatī’s popular Benares temple are aware of her tantric background, the goddess is solely depicted for her patrons at this site as a benign manifestation of Durgā or Mahādevī. Xenia Zeiler has labelled Dhūmāvatī’s transformation as a “saumyaisation” (

Zeiler 2012, p. 190). Other scholars have described analogous transformations as “domestication”, as is the case in Sanjukta Gupta’s study of the Kālīghāt Śakti Pīṭha in Bengal. Here Vaiṣṇava influences have rendered the patron goddess Kālī more and more like Lakṣmī while at the same time attenuating the number of animal sacrifices made to her at the site (

Gupta 2003, pp. 65–66). In a Gujarati context, Samira Sheikh also uses “domestication” to describe the reining in of “questionable practices” such as animal sacrifice and transgenderism at the Śakti Pīṭha to Bahucarā Mātā (

Sheikh 2010, p. 96). While Rachel Fell McDermott similarly refers to Kālī’s “sugar-coating” in Bengal as a domestication, she goes on to attribute the goddess’s elevation and popularization to a multiplicity of additional factors, including Sanskritization, Vaiṣṇavization, urbanization and class (

McDermott 2001, pp. 294–97).

11 All these processes are often closely tied together in modern reimaginings of goddesses. And while no one of these processes provides a complete description of the transformations taking place at many modern goddess temples, they are all useful in varying measure when applied to the ethnographic contexts encountered in this essay. In particular, Sanskritic, Vaiṣṇavic, universal and gentrified elements factor heavily into elite-ness, or at least in the perceptions among the upwardly-mobile as to what putative elites such as Brahmans, Vaiṣṇavas and wealthy Jains do in their religious lives.

12Tantra may also be a factor in reimagining goddesses and gods for mainstream, middle-class and upwardly mobile audiences. Perhaps most obviously, tantric texts have been above all Sanskrit texts, and so tantra offers a potential avenue for Sanskritization.

13 In a more contemporary context, tantra has shown itself to be very much in synch with Indian middle-class lifestyles and religious expressions.

Lutgendorf (

2007) has established as much in linking Hanumān’s popularity in North India to his tantric characteristics. For a minimal expense, cheaply printed tantric manuals provide the literate with easy access to Hanuman’s veritable transformative power without need of an intermediary (

Lutgendorf 2001, p. 284;

Lutgendorf 2007, p. 104–9). In this way, Hanumān devotion is pragmatic and efficient, satisfying the middle-class desire for a tantric “‘quick fix’ for worldly problems” that arise in a hectic, market-driven world (

Lutgendorf 2007, p. 388; see also

Lutgendorf 2001, p. 289).

14 On account of tantra’s popularization and the access it provides to powers that even Brahman priests lack, the Indian marketplace has seen the proliferation of mass-mediated tantra-related cultural products such as religious icons like mantras and yantras, TV serials and even stores, not to mention a wellspring of tantric gurus (

Khanna n.d., p. 2). Madhu Khanna argues that this kind of “

bazaari tantra”, as she refers to it, has “work[ed] its way through the ethos of complex networks of corporate capitalism and has accommodated to the profit-seeking values of the capital oriented market” (

Khanna n.d., p. 5). That being the case, she claims that

bazaari tantra actively engages in shaping Indian popular culture. Now businesspersons, Bollywood stars and even politicians

15 claim tantric affiliations (

Lutgendorf 2001, p. 287). By virtue of this pop culture cachet, it is not uncommon to hear middle- and upper-class Indians making reference to their tantric gurus, or to the acquisition of various

siddhis (supernatural attainments). While Khanna decries

bazaari tantra somewhat scathingly, her work points toward the existence at present of a form of tantra amenable to the Indian middle-class’s consumerist tastes and aspirations, its accoutrements and attainments sufficiently mainstream such that it may actually be capable of aiding in the process of mainstreaming. This applies not just to deities but to devotees as well, as their participation in tantric worship that is satisfactorily Sanskritic, universal and bourgeoisie-friendly may very well mark a performance of upward mobility even more pronouncedly than the tangible material benefits they hope to gain from such religious pursuits.

3. Chinnamastā, Yoginī(s) and Jogaṇī Mātā

Tracing Jogaṇī Mātā’s history and background is complicated due to the nexus of associations evoked by her ties with Chinnamastā and the Yoginī/Yoginīs. While these provide some possible clues as to Jogaṇī’s development in Gujarat, care must be taken not to let her name and imagery lead us to underestimate the localized village aspects that also substantially inform her current imagining. Indeed, an earlier, singular, folk “Jogaṇī” seems to be at the core of the present-day Jogaṇī Mā. In this section, I will proceed from present to past, and somewhat circuitously at that, unravelling the layers to move toward this core.

While Jogaṇī’s Chinnamastā connections are most evident in terms of iconography, they also span her ritual apparatuses. According to the

Śākta-pramoda, a popular tantric manual devoted to the Mahāvidyās published in North India in the late nineteenth century,

16 the Chinnamastā mantra is “

Śrīṃ hrīṃ klīṃ aiṃ vajravairocanīye hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ svāhā” (

Benard 1994, p. 36). The

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat, a cheaply-produced contemporary pamphlet outlining votive rites (or

vrats) to Jogaṇī Mātā, provides the very same series of syllables under the title of “Jogaṇī Mantra”, adding an initial “

auṃ” for good measure (

Nirmal n.d., p. 4). Mantras presented and performed in urban Jogaṇī sites are also virtually identical, with only minor variations. Also commonly on display at these sites is the Jogaṇī Pūjan Yantra, two inverted triangles enwreathed in eight petals and bordered by a square with projections on each of its sides, which follows after the Chinnamastā Yantra.

While her yantra and mantra correspond exactly with Chinnamastā’s, Jogaṇī’s standard Gujarati image matches the more contemporary pan-Indian lithograph imagining of Chinnamastā available at sites like Rajrappa.

17 Were it not for the Gujarati script giving her name as “Śrī Phūl Jogaṇī Mātā” (as per

Figure 1 above), the two images would be interchangeable. This illustration is relatively anodyne when compared to traditional paintings and even early chromolithographs of Chinnamastā. In contrast to many earlier portrayals, the contemporary pan-Indian imagining conceals Jogaṇī/Chinnamastā’s nudity with the garlands of flowers and skulls that she wears, and the same goes for her attendants. The pairing of Kāma and Rati upon whom Jogaṇī/Chinnamastā stands, meanwhile, is fully clothed, their intimacy only hinted at rather than depicted graphically as per eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings.

18 Perhaps most notably, Jogaṇī/Chinnamastā and her attendants bear a golden complexion. While earlier paintings and chromolithographs of Chinnamastā found throughout the subcontinent often represent her as dark-blue or red in skin-tone,

19 respectively suggesting a

tāmasik or

rājasik character, the golden hue appears to mark the goddess as

sāttvik, a point of curiosity considering the blood that streams freely in the image (

Mahalakshmi 2014, p. 204).

20On account of this pronounced overlap of iconography and ritual appurtenances, it is tempting to conclude that Jogaṇī is Chinnamastā. Some Gujarati-language devotional texts posit just such an equivalence. Accordingly, the

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat bears the image of Chinnamastā on its cover. Inside, it uses the two theonyms interchangeably from the outset, with the very first sentence referring to the goddess as “Chinnamastā (Jogaṇī)” (

Nirmal n.d., p. 3). Jogaṇī/Chinnamastā is also homologized with Caṇḍikā, Cāmunḍā and a more general Mahādevī or Śakti, and is subsequently credited with slaying Śumbha and Niśumbha, rendering her akin to Kālī or Durgā (

Nirmal n.d., pp. 3–4). As is perhaps predictable given the Sanskritized Gujarati in which the text is composed, Jogaṇī is dealt with in a decidedly Advaitic fashion, where her name comes to be a transposable signifier for the Great Goddess, assuming the role of divine substratum just as any of the other aforementioned names could. The

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat also links Jogaṇī/Chinnamastā with some other famous faces from Hindu myth and lore. The text explains early on:

Paraśurām was a devotee of Jogaṇī Mā. Nāth Panthī Sadhus also demonstrated piety to this particular Devī. Their own guru Gorakhnāth likewise performed devotion to the goddess Chinnamastā.

Here we see not only the interchange of goddess names, but also an effort to further embed Jogaṇī in Sanskritic mythology by means of tying her to Paraśurāma, the sixth avatar of Viṣṇu, who comes to be associated with Chinnamastā, in some sense, in the

Mahābhārata (3.117.5–19)

.21 The

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat leaves this story untold, though it does assert that it was power from the Jogaṇī

vrat that Paraśurāma used in his battle against the Kshatriyas (

Nirmal n.d., p. 6).

Similarly, the

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat explains that Gorakhnāth gained siddhis from performing its titular votive rights (

Nirmal n.d., p. 6). This reference to Gorakhnāth and the Nāth Sadhus may provide clues as to Jogaṇī’s roots in northwestern India as per emic historiographies, and opens up further resonances for the goddess beyond her depiction as Chinnamastā. Gorakhnāth, a yogic superman who probably lived around the twelfth to thirteenth-centuries CE, was the student of Matsyendranāth, forefather of the Yoginī Kaula aptly named for its founder’s special bond with these female spirits.

22 In the thirteenth century

Gorakṣa Saṁhitā, the purported author Gorakhnāth continues this Kaula tradition, concluding each chapter with a declaration that the text is transmitting the secret doctrine of the Yoginīs (

Dehejia 1986, p. 32). Gorakhnāth is also credited with the establishment of the Nāth Sampradāya, which flourished in western India. Gujarat in particular has a high concentration of Nāth Siddhas, who have monasteries and temples throughout the state (

White 1996, p. 118). Gujarat’s topography also bears witness to Gorakhnāth’s lasting legacy. South of Junagadh in the Saurashtra region sits the Girnar Mountains, the highest peak of which is named for Gorakh (

White 1996, p. 117–18;

Briggs [1938] 1973, p. 119).

23 Predictably, the site abounds with various shrines and sacred spots hallowed by the Nāth Siddhas, and has been an important pilgrimage site for the order since at least the thirteenth century (

White 1996, p. 118). Yoginīs—or Jogaṇīs, in the local parlance—are also said to be found in the Girnar area, to such an extent that they too are part of the topography; there is, for instance, a Jogni Hill among the Girnar range (

Desai 1972, p. 40). At the nearby Kālīka Hill, the Jogaṇīs were thought to take the lives of visitors, and it was commonly understood that anyone who ventured into the area never returned (

Enthoven [1914] 1989, p. 46). In referencing Gorakh and the Nāth Sadhus, then, the

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat implicitly situates its eponymous goddess at Girnar. Indeed, Girnar and the Nāth Siddhas seem to represent fountainheads of Jogaṇī Mātā’s present-day significance; as we will see, some of her officiants trace their gurus to this site.

24 Moreover, the connection the

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat calls to mind between Jogaṇī Mātā and the Yoginī Kaula prompts us to interrogate the “Yoginī” resonances, both Sanskritic and regional, already rooted in the name of the goddess it describes.

It would be greatly remiss if I did not first mention that Chinnamastā herself is occasionally referred to as “yoginī.” For example, in its hundred-name hymn dedicated to Chinnamastā, the

Śākta-pramoda lists “Yoginī” among the epithets. While this may speak to her yogic abilities as much or more so than it does to her identity as a female spirit,

25 the

Śākta-pramoda does refer to Chinnamastā in passing as a yoginī in its

stotra portion (

Benard 1994, p. 41).

26 This designation of “yoginī” may be a holdover from Chinnamastā’s well-documented Buddhist roots. Benoytosh Bhattacharyya has argued that Chinnamastā is a later Hindu adaptation of the Vajrayana Buddhist goddess Vajrayoginī, who is likewise depicted in her “Chinnamuṇḍa” form as feeding her attendants with sanguinary streams from her self-severed neck (

Bhattacharyya 1964, p. 159). It is on the basis of the names of Vajrayoginī’s attendants—Vajravarṇanī and Vajravairocanī—mentioned in her mantra in the twelfth century CE

Sādhanamālā that Bhattacharya formulates part of his argument. If the “Vajra” prefix indicates their Buddhist character, the fact that it is dropped in the attendant’s names as given in the Hindu literature—Varṇanī and Ḍākinī—suggests an attempt to make the deity less Buddhist (

Bhattacharyya 1964, pp. 160–61).

27 Oddly enough, “Vajravairocanī” remains part of the Chinnamastā (and Jogaṇī) mantra today, as we have already seen. All told, the link with the name “Yoginī”, for Chinnamastā as for Jogaṇī, could simply reflect Chinnamastā’s development out of the Buddhist Chinnamuṇḍa Vajrayoginī.

But the multifarious connotations evoked by the yoginīs are not so easily exhausted. Scholars have made much of the term “yoginī” on account of its numerous semantic trajectories, singular and plural, Sanskritic and folkloric,

28 and so even in Gujarat alone we are left with a complex matrix of yoginī connections to explore. Starting with the Sanskritic—or at least pan-Indian—understanding of the term, the widespread cult of the sixty-four yoginīs is conspicuous by way of its virtual absence in Gujarat. Despite the preponderance of yoginī artifacts in neighboring Rajasthan, among them paper and cloth Chakras dedicated to the plurality of female spirits, there are no well-known sixty-four yoginī temples in Gujarat (

Dehejia 1986, p. 75). In her exhaustive study of such locations across India, Vidya Dehejia cites Palodhar in Mehsana district as the only Gujarati example, which she reports “has apparently crumbled away” (

Dehejia 1986, p. 80). There is, in fact, a tiny modernized Cosaṭh (“sixty-four”) Jogaṇī temple up and running in Palodhar at present, a few hundred yards away from a much older site decorated with carvings of female figures. Whether the latter structure is a remnant of the ancient yoginī cult or not, the modernized temple is a fairly standard Hindu site, drawing only nominal relations with the sixty-four yoginīs or Chinnamastā, at least from the perspective of the

pūjārī with whom I spoke. As a case in point, the central shrine is dedicated to a singular Śakti, her head intact. The

pūjārī informed me that there was a yantra underneath this image, though beyond this, there were few other tantric elements, and certainly no imagery of Chinnamastā or Jogaṇī. In this way, the temple parallels “sixty-four Yoginī” temples in Benares studied by

Ferrari (

2013) and

Bisschop (

2013). At these sites, as in Palodhar, there is little to no evidence of tantra or of the iconography and worship of the sixty-four divinities (

Ferrari 2013, pp. 149–51). In their place is the non-tantric goddess “Chaumsathī Devī” who is basically a modified form of Durgā, a singular deity standing in for all sixty-four (

Ferrari 2013, p. 149;

Bisschop 2013, p. 55). Cosaṭh Jogaṇī Mātā of Palodhar, then, is not Chinnamastā, nor is she strongly associated with Jogaṇī Mātā. While a few Jogaṇī Mātā sites, as we will see, claim some degree of acquaintance with Palodhar, this is definitely not found across the board.

The Yoginīs/Jogaṇīs show up as a plurality more frequently in the Gujarati folk tradition. Alexander Kinloch Forbes, a colonial administrator and founder the Gujarati Vernacular Society, states in his 1878

Ras Mala that yoginīs helped in averting drought. During a dry spell, low-caste exorcists called

bhuvās were acquisitioned to channel the Mātāji and inquire as to the lack of rainfall (

Forbes [1878] 1973, p. 605). The

bhuvā would then put in a request for food sacred to the Devī, and a feast was subsequently set out beyond the eastern gate of the town in question. These offerings were served in broken earthen vessels representing human skulls, out of which the yoginīs supposedly preferred to eat. This banquet for the Devī and the yoginīs, the latter seemingly playing their traditional role as attendants, was deemed successful if rain returned to the area (

Forbes [1878] 1973, p. 605). The yoginīs were not always so munificent, as they were also held responsible for the spread of contagious diseases among human beings and cattle (

Enthoven [1914] 1989, pp. 65–68). The only solution to epidemics caused by the sixty-four Jogaṇīs was the offering of a goat or a male buffalo, or else, once again, the observance of a feast in their honor (

Enthoven [1914] 1989, p. 80). In Girnar, as in other regions, the Yoginīs were specifically called upon when the area was afflicted with cholera (

Chitgopekar 2002, p. 105).

These folk rites related to disease shed light on the interplay between the plural and singular nature of the Jogaṇī. Gustav Oppert, writing in 1893, reports that his informants distinguished between three kinds of “Yōginīs” [sic]:

Pul (flower),

29 Lāl (red), and

Kēśur (hair).

30 The first is integral in the process of casting out disease:

They are invoked when epidemics, especially cholera, rage in the country. With their hair hanging over their shoulders, their faces painted with red colour, the Bhuvas assemble at a prominent Yōginī-temple, and after having partaken of a liberal supply of intoxicating liquor, jump about, pretending that the Yōginī has entered them, and that they speak in her name. At first the Pulyōginī appears alone, complaining about the neglect she and her sisters have suffered threatening the arrival of her sisters Lālyōginī and Kēśuryōginī, if she is not properly appeased now. The people made then in their homes the requested sacrifices consisting of a goat, rice, ghee, and liquor, and in the evening Pulyōginī is in a small carriage, resembling a children’s toy, taken with tomtom beating out of the town, and in the dead of night drives to the limits of the neighbouring village, where the chief Bhuva leaves her without looking backward. The inhabitants of the next village when they find the carriage on the next morning are frightened by the arrival of Pulyōginī and send her with similar ceremonies to another village.

This passage is edifying for a number of reasons. Firstly, it describes the decidedly non-

sāttvik,

bhuvā-based rites that took place in what appears to have been a rural or village-based context. Equivalent forms of possession—referred to as “

pavan”, literally “getting a wind” of a divinity

31—can still be found at many goddess shrines and temples today, Jogaṇī sites included. Sacrifice and liquor oblations, while less common due to animal cruelty laws and Gujarat’s “dry-state” status, also occur at some Mātā

derīs in rural or depressed-class areas, which I witnessed on several occasions during my fieldwork. Even more importantly for our purposes, the passage establishes that yoginīs, while treated as a group, were also portrayed as individual entities in Gujarati folklore and approached as such. “Pulyōginī” bears particular significance in this cholera rite, and speaks to the prominence of a singular, discrete Jogaṇī in Gujarati village religion in the nineteenth century. The “Pul” in “Pulyōginī” also corresponds directly with the “Phūl” prefix commonly bestowed upon Jogaṇī in many of her modern lithographs.

The singular yoginī or “Jogni” is mentioned in other colonial-era ethnographic writing as well.

The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (

Campbell 1901) lists Jogaṇī—rendered here as “Jogni”—as one among many Gujarati words referring to “outside spirits” or ghosts who are female. Also on this list are Melaḍī, Cuḍel, and Śikotar, all of which at present bear the title Mātā, and all of which have seen major modern temples erected in their names as well (

Campbell 1901, p. 417). Alongside these other female divinities, Jogni is elsewhere designated by the

Gazetteer as being among “goddesses to whom blood offerings are made” (

Campbell 1901, p. 406), thereby corroborating the account of the sacrifice from Oppert. The

Gazetteer also provides a list of the various Dalit and lower castes who perform such blood offerings, including the Vaghris, the pastoralist Bharwads and Rabaris, as well as Kolis and Rajputs, all of whom are among Jogaṇī Mātā worshippers today (

Campbell 1901, p. 406).

32 More recent ethnographies also reference Jogaṇī as a single divinity for similar caste groups. Lancy Lobo reports that Thakors, a low status group identifying with the Koli caste category, worship Jogaṇī as a “lower Mātā” (

Lobo 1995, p. 142). This group features in a folktale I heard during my fieldwork wherein Jogaṇī beheads a Thakor married couple who did not honor her appropriately. While this story may be a by-product of Jogaṇī Mātā’s Chinnamastā imagery, it may also be based on more general connections between the goddess and blood, specifically bleeding related to the head. Joan Erikson, for instance, in her work on temple textiles in Gujarat, records that Jogaṇī is the goddess consulted by individuals suffering from severe nosebleeds or head wounds (

Erikson 1968, p. 28).

Thus, while the term “Jogaṇī” was no doubt in conversation with a panoply of pan-Indian and local semantic connotations, both singular and plural, there is also evidence that “Jogaṇī” referred to a standalone spirit in the folk Gujarati context. Underneath this convoluted plurality of meanings, there is a singular entity—a uniquely Gujarati “Jogni” who was both ghost and goddess. Associated with diseases like cholera, nosebleeds and head wounds, she was worshipped via

tāmasik means such as blood offerings and liquor oblations as something of a proto-Mātā. This appears to be the core of the current-day Jogaṇī, affixed now with the Mātā title.

33 The historical overlap with regard to castes that pay her worship, the ritual use of

tāmasik substances and intoxicated

pavan at some of her village or non-elite sites,

34 and the stability of the prefix “Phul” for a singular “Jogaṇī” all suggest a high degree of continuity between the singular “Jogni” or “Pulyōginī” of the past and the Jogaṇī Mātā who is depicted as Chinnamastā in the present.

And speaking of Chinnamastā, what stands out in all the ethnographic accounts cited above relating to Jogaṇī, both colonial and even later, is what is

not mentioned. That is, none of the authors previously referenced describe Jogaṇī as bearing the self-decapitated iconography of Chinnamastā. This is somewhat surprising given the proclivity of the colonial gaze to fixate on such evocative images. This gives the impression that Jogaṇī’s Chinnamastā iconography is a relatively recent overlay to the singular ghost-cum-goddess Jogṇī/Jogaṇī. The question of

when exactly the adoption of this imagery took place remains harrowing, however. When I asked people at Jogaṇī temples to estimate what decade they remembered the goddess taking on her current lithograph illustration as Chinnamastā, I was told that this had been her image since time immemorial, and could be traced back to Jogaṇī’s creation of the universe. Speaking in terms of a more etic historiography, this pairing of Jogaṇī with the Chinnamastā image likely took place in the past two or three decades. The availability of Chinnamastā lithographs in other parts of India may provide some clue as to just how recently Jogaṇī came to be connected to the image. While Chinnamastā’s chromolithographs date back at least as far as the 1880s, she has only seen her devotional images widely circulated in recent times, at least if the curio shops surrounding her Cintapūrṇī temple complex in Himachal Pradesh are any indication. It was at this complex that Elisabeth Benard, in the course of doing fieldwork for her 1994 study of Chinnamastā’s temples, was informed by

pūjārīs that household devotees visualize Chinnamastā solely as Durgā when worshipping in their homes. No Chinnamastā prints were sold at the temple’s outlying shops, as her form was thought to be of interest only to yogis and other adepts (

Benard 1994, p. 47, n. 23). Absence of proof is not, of course, proof of absence, but Cintapūrṇī provides at least some indication that

sāttvik, gold-complexioned Chinnamastā images (and the Gujarati Jogaṇī images patterned after them) may have only become widely available after the mid-1990s.

Regardless of the date of its introduction, the Chinnamastā imagery does not alienate the crowds that flock to Jogaṇī temples in Gujarat, including their middle-class and upwardly mobile sections. While Mātās like Jogaṇī sometimes occasion a negative perception among some Jain, Baniya and Brahman elites in view of their link with tāmasik practices and lower castes, the gold-complexioned Chinnamastā imagery seems to work in tandem with the relations to Paraśurāma and Gorakh in moving the goddess outside of the village context toward a safer, sāttvik, Sanskritic mode. What results is the Jogaṇī Mātā we meet in the temples of urban Gujarat, a deity quite different from the Durgā-like Cosaṭh Jogaṇī Mātā, but still treated like a Great Goddess in her own right.

4. Ethnography of Urban Jogaṇī Sites

In order to better understand how Jogaṇī’s village and tantric resonances function in a contemporary Gujarati context, I carried out fieldwork at a number of shrines and temples dedicated to the goddess in and around Ahmedabad. Here I focus on three urban sites that attract a middle-class, upwardly mobile following, the first located in Gandhinagar, the Gujarat capital, and the other two in the Naranpura and Odhav sections of Ahmedabad. At these sites I undertook participant observation of temple rituals and routines while also partaking in conversations, mostly unstructured, with officiants and patrons.

4.1. Gandhinagar

Tucked away amongst conjoined houses in a comfortable, tree-ensconced residential sector of Gandhinagar is a small but popular Jogaṇī Mātā shrine. The shrine operates out of a tiny room in the home of Anitabahen (see

Figure 2), an Ayurvedic nurse, and her husband Mukeshbhai, who works for the state government distributing electricity. Hailing from the Barot community, a bardic caste thought to be strongly linked to goddesses,

35 the couple founded their home-based shrine just over a decade ago. Both have

pavan of local deities, Anitabahen from Jogaṇī Mātā and Mukeshbhai from Śikotar Mā and Gogā Mahārāj.

36 While it takes Mukeshbhai considerable effort to get

pavan, Anitabahen can get it spontaneously and with greater intensity. For this reason, she represents the spiritual focus of the shrine.

Anitabahen first got pavan as an adolescent, when she was approached by a young girl who offered her a flower (or phūl), the predominant Jogaṇī symbol. Initially skeptical, Anitabahen passed up the offer, and thereafter experienced pain in her chin and stiffness in her neck. Upon consulting a bhuvā about the ailment, it was revealed that the mysterious girl was the svarūpa of Jogaṇī from Palodhra. Hearing this, Anitabahen accepted her pavan, which only strengthened after she and her husband co-founded their shrine. Now she is able to link up with the goddess at any time, though her pavan is especially pronounced, she explains, during the nine nights of Navratri. For the duration of the festival she goes on leave from her work and gives up all housekeeping duties such as cooking and washing, which are taken on by other family members. She also observes a fast, consuming only lemon juice, milk and water. Day and night throughout the festival she stays on the floor of the shrine, even sleeping there, waking around two or three in the morning to meditate and recite mantras. Drifting out of her conventional consciousness, she plays and talks with Jogaṇī Mā, and when people arrive at the site she is able to announce accurately the purpose of their visit.

Anitabahen describes her life’s work as a process of transferring her pavan of Jogaṇī to her patients, both in her home and in the hospital. When they visit her at her home shrine, she repeats mantras and ślokas in her mind or under her breath to accomplish as much. At some point during this process, she or Mukeshbhai applies a cloth to the visitor, attempting to remove “negativity” (doṣ). All the while, recordings of Sanskrit chants play in the background. Consultation also concerns everyday problems in devotee’s lives and facilitating Jogaṇī’s fulfillment of their wishes, Anitabahen reading beads to provide solutions. One recurrent request involves securing devotees visas to the United States and other western countries. During my visits, a number of people came in seeking aid for just such a desire, as was the case for one Patel woman who was trying to get American work visas for herself and several family members. From Anitabahen’s own perspective, however, the shrine’s primary achievements involve the alleviation of health problems. In this way, her pavan allows her to heal people in two ways, as she conceives it—directly as the Mātāji, and secondarily through her Ayurvedic nursing. She told me of one woman who was under intensive treatment at a leading cardiac hospital, heart surgery her only conceivable hope for survival. This woman started to visit the shrine regularly, and now needs only minimal medication for her condition, having been blessed by Jogaṇī’s cosmic energy. Anitabahen attributes the entirety of her success at healing and granting requests to her role as a conduit for Jogaṇī, whom she frames in a very Advaitic mode as the most ancient power in the universe from which all other gods and goddesses are created. It is Jogaṇī’s self-beheading that inaugurated the universe, Anitabahen explains, and so the goddess is able to manifest in any part of the world. Because she has the widest jurisdiction, it follows that Jogaṇī is the most effective spiritual force available, in Anitabahen’s words a “Brahmanical” power that brings prosperity, healing and also fertility.

The effectiveness of her method of healing has gained Anitabahen a loyal local following. People show up at the shrine from the early morning to the late evening, and she and her husband are continually handling phone calls from prospective visitors. This following, they inform me, has also spread to other parts of India and even abroad, and so they have accumulated devotees in the USA, the UK, Australia and Canada. During one of my early visits, Mukeshbhai proudly showed me his ringing cellphone, displaying a number with an American area code. Indeed, much of their support comes from Patels based in America. Locally, major events draw crowds well beyond the capacity of the shrine’s tiny confines, as is the case at the yearly patottsava, which has brought in as many as 1500 people. In order to provide more space for their devotees, the couple plans to build a full-scale temple nearby on the strength of local and international donations. Despite their success, Mukeshbhai tells me that he and his wife are not seeking big commercial gains. Humility is at the core of their self-definition—that is, they only want the status of sevaks or servants rather than bhuvās, because bhuvās are synonymous with making income and greed.

Tantric imagery covers virtually every square inch of this site, the shrine room festooned with yantras as well as numerous icons of Chinnamastā/Jogaṇī in lithograph prints and framed statuettes. Standing out among these Chinnamastā-styled icons is a plug-in three-dimensional lithograph which simulates the streams of blood from Jogaṇī’s neck in blinking red LED. Yantras sit all around the main mūrti, the most prominent being the Jogaṇī Pūjān Yantra. During consultation with her followers, Anitabahen murmurs mantras, counting them off on prayer beads while consulting the goddess. Additionally, there are sixty-four oil-lamps which are lit and offered on peak days such as Sunday and Tuesday, a conscious nod to the Cosaṭh Jogaṇī temple at Palodhra, which Mukeshbhai visits at festivals. When I inquired about the tantric nature of these ritual and visual apparatuses, Anitabahen and her husband were quick to set apart what they did from tantra. Mukeshbhai was particularly skeptical of tantrism, as his grandfather had apparently engaged in some tāmasik tantra in the past and had suffered undesired consequences. Having learned a lesson from his grandfather’s dabbling, Mukeshbhai only deals in the sāttvik, and the same goes for his wife. Their pūjā is entirely vegetarian, with coconuts being the only thing sacrificed in the shrine. In the event that a devotee ever comes in suffering from any sort of tāmasik or malevolent sorcery, Anitabahen makes sure to respond as quickly as possible. On the whole, Mukeshbhai says he does not want to deal in tantra, a kind of power which he differentiates from that of the pavan he and his wife experience. Their pavan, in his view, especially Anitabahen’s, is a direct connectivity with the goddess. Mukeshbhai’s framing of the rituals at his home shrine reflects a tendency I found at many other Gujarati sites to delink a given mātā from bhuvā-based practices, with so-called “black” or “tāmasik tantrism” often included therein. Such practices are held in suspicion by the Gujarati Hindu mainstream, as they would seem to attenuate the power of the goddess through their reliance on an intermediary who is both out for profit and willing to deal in negative forces.

4.2. Naranpura

Comparable attitudes can be found at the the Jay Mātāji Mitram temple to Jogaṇī Mā in the Naranpura section of Ahmedabad. This sleek, medium-sized temple and surrounding complex, constructed in the early 2000s, is centered upon the figure of Maa Laadchi, a woman of pastoralist origin who has had an ongoing pavan of Jogaṇī since her adolescence. After suffering a snake bite, Laadchi started to experience pavan-like symptoms, though she was not entirely sure what was happening to her and, like Anitabahen, did not immediately open up to the presence of the goddess. Her youth was from then on fraught with troubles until she was assisted by her maternal aunt, who herself had pavan of her village Jogaṇī and transferred it to Laadchi. Laadchi subsequently began providing solutions to people’s problems and gained a following that has further burgeoned with the construction of the Naranpura temple.

The site has over time come to attract a diverse following, including some fairly well-heeled, upwardly mobile patrons. Among my foremost conversationalists were a number of English-speaking trustees with prominent occupations, including Jayram, a Rabari man in his early thirties who works as cameraperson for an Ahmedabad news station, and Dr. Patel, a physician at a local hospital. While well-employed, Jayram and Dr. Patel, among others at the Naranpura temple, seem to be undertaking nonetheless a continuing negotiation of their middle-classness and social status, still working against lingering upper-caste stigmas toward Patels or Rabaris. That said, the complex also attracts the patently elite. As a case in point, Jayram was proud to report that Narendra Modi’s family has visited the site on a number of occasions.

Every Sunday and Tuesday, a long line of visitors winds through the temple waiting for an opportunity to meet with Laadchi. These sessions usually involve a method of divination referred to as “sitting

patla”, which involves throwing seeds to chart a course of action for solving a devotee’s concerns, a carryover from earlier

bhuvā-based practices (see

Figure 3). Like Anitabahen, Laadchi confronts visitor’s health problems, among them diabetes and cancer. These diseases are framed as “negative power” which has entered a person’s body, and when their sickness proves incurable by the best efforts of an allopath, I was told, people then come to Laadchi. As Dr. Patel described it, the cures that result thereafter are 99% on account of the Mātāji, 1% on account of the overseeing physician. Laadchi also handles infertility and, as is characteristic of

mātā sites, there are stories of women in their late forties who, after years of previous barrenness, conceived children shortly after visiting the temple. As it was explained to me by Dr. Patel, the temple takes on any “time-being” problem with the aim of transferring people from the “ocean” to the “green”. That is, Laadchi always reassures people that, while they may be temporarily drowning in an ocean of problems, after coming to the temple they will eventually find the green and then the gold—specifically, land and money. It is not just expedient resolutions that come to temple devotees, apparently, but prosperity as well. Accordingly, Laadchi is just as likely to advise on business deals and career moves as she is to cure ailments. For instance, during one of my visits I met a Brahman woman who had come to give thanks for a wish that had been fulfilled pertaining to the success of her daughters’ careers abroad in the United States and Canada. By virtue of its gaining reputation for very quick, very tangible results, the Naranpura temple attracts a wide range of visitors from all over Gujarat, as well as India at large.

While the temple grounds are frequented by a significant contingent of Barwads and Rabaris, prominent members of the temple assured me that all castes and creeds attend, including people from the village, and even Christians and Muslims. These visitors span all economic capacities. In many cases, Dr. Patel explained, the underprivileged received healing from the temple they could not otherwise afford from hospitals. The Mātāji, I heard again and again, sees no difference between people, and so all groups are welcome. What was not welcome, I was told, were any people who betrayed, as the trustees phrased it in English, an attitude that was “hi-fi”—apparently referring to a disposition of class or caste-based elitism. This spurning of the hi-fi not only combats snobbery, but also actively encourages the performance of middle-classness in that it promotes a spirit of inclusivism, just one among many middle-class values cultivated by the Naranpura temple. The clean, tidily kept environment and well-ordered queue further underscored the temple’s middle-class sensibilities, as did the overall emphasis on material prosperity. Not only did the temple boast three new automobiles, but on one of my early visits, trustees handed out glossy fliers promoting a temple-sponsored raffle that advertised as prizes flat-screen TVs, air conditioners and motorcycles, among other commodities. Complementing these markers of middle-classness were upper caste influences, most notably vegetarianism, and so non-veg food and animal products are strictly forbidden on the Naranpura temple grounds. Collectively, this constellation of sensitivities suggests the Naranpura temple and its followers foster some degree of upward mobility, involving elements of Sanskritization and/or Vaiṣṇavization alongside gentrification and/or bourgeoisification. Although not elitist by any stretch, the temple still wanted to distinguish itself from other Mātā temples. This seemed to be the motivation on one occasion when Jayram saw me glancing at some advertisements for other Mātā sites outside of Ahmedabad papered to a wall a few feet away from the temple, and approached wanting to make sure I was not confusing the Naranpura site with any of these.

While tantric accoutrements were less concentrated throughout the Naranpura temple grounds than at other Jogaṇī sites, there were still a number of yantras and Chinnamastā images. The trappings of tantra are more readily discernible in formulations of the Naranpura temple’s power and the immanent availability thereof. When I asked what separates Jogaṇī from other goddesses, both Jayram and Dr. Patel gave me variations of the somewhat standardized Advaitic response. Jayram said that Jogaṇī is one, and her expression depends on the community worshipping her. Dr. Patel modified this slightly by saying that all goddesses, like doctors, are essentially the same, though a person ends up going to the one that works best. For Dr. Patel and other temple attendees, Jogaṇī is what works. Dr. Patel then went on to liken the singular, all-powerful Great Goddess to a CEO with a plurality of assistant managers, directors and employees. These middle-management types are the local goddesses and their manifestations such as Laadchi who provide more immediate results to the devotees, and allow people to participate in Jogaṇī’s power directly. It is the power of this temple alone, Dr. Patel explains, that draws in passersby who can benefit from it most. But the power at the Naranpura temple is not simply a nebulous philosophical construct; rather, it is both highly efficacious and pragmatically directed. Having noted the busy, fast-paced nature of city life, Dr. Patel stressed that Laadchi cares first and foremost about results, and so her role, then, is primarily in easing the delivery of any given devotee’s requests. Be that as it may, when I brought up the topic of tantra with Jayram, he was quick to shake his head. Jayram tells me there is no tantra-vidyā at the Naranpura temple, only the reading of seeds and the faith of the people. As a whole, neither he nor the other major players at the temple thought particularly highly of the tantric label.

4.3. Odhav

The Gandhinagar and Naranpura sites are representative of most Jogaṇī locations I visited, where an explicit association with tantra is either denied or de-emphasized. There are, however, exceptions, one such being the small Jogaṇī Mātā temple in Odhav, a residential and commercial suburb of Ahmedabad. This temple began as a small

derī in 1967 when the area was still fairly remote, and the temple was built up around it in the 1970s, having been further expanded in the past two decades. The temple is currently fronted by Dhananjay, who claims affiliation with the Rāmānandī Sampradāya, a north Indian Vaiṣṇava ascetic lineage,

37 and self-identifies as a Brahman, donning the sacred thread. Rāmānandī Sadhus, he explained to me, have a special relationship with the yoginīs, representing sixty-four dimensions of the one Shakti who are responsible for directing Rāmānandī family goddesses (or

kuldevīs). Dhananjay also claims affiliation with the Nāga Sadhus, a sub-order of ascetics closely tied to the Nāth Siddhas (

White 1996, p. 254). Dhananjay’s own guru lives at Girnar, evidently the Gujarati hotbed of Jogaṇī(s) as was intimated by the

Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat. Śaktis and Jogaṇī have played an integral part in the religious life of Dhananjay’s ancestors, as he can trace his own

pavan back five generations. Dhananjay established his personal connection to Jogaṇī in his late teens, when he received his first

pavan. Since then, his

pavan has remained relatively understated, occurring in very short but very intense bursts, usually only on holy days such as Shivaratri and Holi, among others. Though he is trained in the family business of refrigerator and air-conditioning repair, the majority of Dhananjay’s energy is dedicated to the temple and to the study of tantrism.

The temple itself operates much like other Jogaṇī sites, based upon consultation between officiants and visitors, though its following is smaller and mostly local. Temple patrons are mainly Rabaris with some Barwads intermixed, though they include an assortment of other castes and even some Sikhs and Muslims from the surrounding community. During Navaratri the crowds swell, with upwards of 400 or more people visiting the temple in the evening throughout the course of the festival. As for day to day routines, Dhananjay’s father handles more standard requests from visitors, using a feather broom to whisk away negativity and bestow blessings, while tantric tasks are delegated to Dhananjay. In these cases, Dhananjay fixes a timeslot to perform the necessary rituals, which are largely focused upon mantras and, on occasion, the construction of elaborate yantras out of multicolored food grains. These help with the usual difficulties brought to

mātā shrines; as Dhananjay’s father phrases it: “All middle-class problems are solved.” The temple also seems to have evolved with the middle-class and upwardly mobile in mind. In the last ten years, the sacrifice of goats has stopped, and now symbolic substitutes such as gourds and betel are used under Dhananjay’s direction. Like the other middle-class Jogaṇī officiants, Dhananjay also accentuates the temple’s affluence. The temple itself appears not to be suffering financially, as it sponsors a half-dozen

havans of considerable scale every year, with a team of Brahmans hired for these events (see

Figure 4). These

havans, Dhananjay assures me, cost an exorbitant amount, but the goddess’s blessings have easily defrayed the expense. In fact, Jogaṇī’s Chinnamastā imagery actually encodes the prosperity that awaits her devotees. In Dhananjay’s interpretation of the lithograph print, Jogaṇī stands not on Kāma and Rati, but rather upon Viṣṇu and Lakṣmī.

38 With Viṣṇu and Lakṣmī literally under foot, Jogaṇī secures for her devotees not only the blessing of Viṣṇu, but the lucrative rewards of Lakṣmī, as well.

When I inquire deeper into the specifics of the Chinnamastā image, Dhananjay explains that it depicts Jogaṇī after slaying Raktabīj, thereby putting the goddess in a role closer to that of Durgā or Kālī, which we have already seen her assume in the Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat. Her nudity is strategic, Dhananjay claims, as it serves to distract her demonic foes. The ostensibly violent imagery of the auto-decapitation, in his view, is also created out of consideration for people from lower castes and classes, who come to Chinnamastā at the end of their workday with feelings of frustration, anger, fatigue, and failure. All of this wild excitement, as he refers to it, is absorbed and withdrawn by this tāmasik imagining of the goddess, which she takes on in the evening. By morning, however, she is soft and sāttvik. The goddess as Chinnamastā, then, in Dhananjay’s reading, appears to have transformative power, sublimating the tāmasik urges of non-elite groups and rendering them sāttvik. In this way, her image as Chinnamastā is tantamount to a purifying force. In Dhananjay’s view, Jogaṇī can be both tāmasik and sāttvik, as well as rājasik, a testament to her all-encompassing nature. With this transcendent theological imagining in mind, he assures me that Chinnamastā is just one name of Jogaṇī, whom he describes as being akin to a giant power station that has channels of distribution numbering sixty-four or more. Moreover, as with other Jogaṇī sites we have visited, the main goddess is again attributed with the inception of the cosmos, at which she appeared first on the scene as the primordial jyot, or flame. And, once again mirroring the Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat, Dhananjay also made repeated references to Jogaṇī’s extensive Sanskritic itihās, or history, which he claims can be traced back to various Vedic and Purāṇic texts. Chinnamastā, then, is just one among many facets of Jogaṇī’s all-embracing Sanskritic and Advaitic character.

Unlike the other Jogaṇī affiliates we have met, Dhananjay openly affirms that Jogaṇī is tantric and that he himself is a tāntrika. This tantric aspect is plainly reflected in the environment and rituals of the temple. Inscribed high up on the door-facing wall are the syllables of the Śrī Jogaṇī Mātā Mūlmantra. There is also a yantra, Dhananjay informs me, underneath the central Jogaṇī mūrti. It is necessary to have these apparatuses in place, Dhananjay explains, to maintain not just prosperity but also peace of mind, as they all help to digest the negative symptoms he takes on from visitors. It is for this reason that, on Kālī Caudas, the most inauspicious day of the year, he contracts an extensive tantric havan, or fire sacrifice. After midnight on this evening, Dhananjay and his team of Brahmans complete 125,000 mantras in order to recharge the energy of the temple for the entirety of the dawning year. The havan, I was told, is highly effective due in part to the temple’s location within several blocks of what used to be funerary grounds. Accordingly, interspersed between the mantras are performances of arthī for Jogaṇī as well as an assortment of cremation ground deities like Bagalāmukhī, Bhairava, and Kālī. Because of his tantric erudition and his Jogaṇī pavan, Dhananjay maintains an esteemed place among tāntrikas in Ahmedabad, and even acknowledges involvement with more secretive tantric rites. A number of these, he claims, have been commissioned by members of the city’s elite, such as prominent bank managers trying to affect CEOs and political figures. When some of these rites began to incorporate black magic, however, Dhananjay ceased to attend.

Dhananjay defines his tantric activities in counterpoint to such malevolent undertakings. When I ask why other Jogaṇī affiliates would be so quick to dismiss tantra, Dhananjay first suggests to me that 90% of people do not have any real systematic knowledge of tantra, and for that reason, they fear their lack of true understanding will be outed. Secondly, many have come to associate tantra with negative ends like the black magic mentioned above. Dhananjay estimates that for 90% of tāntrikas, the goal of their practice is negative “black tantrism” seeking to cause ill to others. By contrast, he only takes part in positive or “white tantrism”, which is employed solely to cure physical and psychological pain. True tantra is, in his view, therapy to cure a patient. However, with yantras and mantras as with medicine, every tablet has a side effect if not taken in the proper dosage. Therefore tantra, like medicine, is a deep science that should be applied precisely and carefully. When spoken by a Brahman, a mantra becomes like a “guided missile”, as Dhananjay phrased it, the implication being that more tāmasik, less Brahmanic, and less benevolent bhuvās are using an exceedingly powerful weapon indiscriminately. Dhananjay assures me that his tantra is strictly sāttvik and Brahmanic, as the Brahmanical and Sanskritic further assists in preventing ill effects of the negative residue a white tāntrika inevitably takes on from his clientele. While Jogaṇī can be tāmasik, sāttvik or rājasik, she is nonetheless central in attaining to this Brahmanic standard, as Dhananjay sees her as being highly Sanskritic when compared to other goddesses, mostly on the strength of her substantial Vedic and Purāṇic itihās.

While Dhananjay was the only Jogaṇī affiliate I found who openly avowed a tantric affiliation or identity, in differentiating two types of tantrism, he provides some insight as to why most Jogaṇī temples de-emphasize the goddess’s tantric components. Evidently, they do not want to risk being connected with a form of religion that still carries with it some negative connotations. That said, while Anitabahen, Laadchi, and their followers, among others, may downplay or deny tantric appurtenances, they still offer visitors—as does Dhananjay—access to some degree of “white” tantrism that brings its benefits rapidly and just as importantly removes “negativity”, a concept that was referenced at all three sites. Indeed, Anitabahen, Laadchi and Dhananjay share a direct connection to the Great Goddess via pavan which remains uncorrupted by the avarice of bhuvās and black tāntrikas, who deal in destructive forces for profit. Even when it goes unacknowledged, this positive tantric power seems to play a fundamental role in making Jogaṇī temples appealing for an increasing base of devotees who aspire to a long and prosperous middle-class lifestyle in India or abroad.

5. Conclusions

Although Jogaṇī was at one point appeased through sacrifices and liquor oblations, the Jogaṇī Mātā sites we have visited in and around Ahmedabad appear to be participating in an ongoing effort to reimagine and reconfigure their patron goddess. This involves a number of imbricated strategies. While these sites have maintained some village elements like patla and pavan, all of them appear to have Sanskritized in view of their emphasis upon vegetarianism and symbolic sacrifices, as well as their deployment of Sanskrit texts, recordings and ritual apparatuses, and even the employment of Brahmans. These converge to actualize the kind of Sanskritic, Brahmanic imagining of the goddess put forward in widely-available devotional pamphlets like the Śrī Jogaṇī Vrat. In the text as in the temples, this preference for the Sanskritic informs several variations of Advaitic theology for Jogaṇī, each of which figures her as interchangeable with—if not fully embodying—the Great Goddess in a universalistic mode. In their intrinsic refinement, these Sanskritic ritual modes and universalized theologies coincide with middle-class sensibilities, which are readily identifiable in the demonstrations of material prosperity and cosmopolitan, intercontinental ambitions that abound at urban Jogaṇī sites. Middle-class values also inspire the sites’ efforts toward inclusiveness, as well as more subtly gentrified considerations such as cleanliness and orderliness. Far removed from the Phūl Jogaṇī of the village, Jogaṇī Mātā has been effectively Sanskritized, universalized and gentrified. These processes, however, have not necessarily “sweetened” her main image.

Bloody though it may be, Jogaṇī’s tantric imagery as Chinnamastā does not run contrary to this Brahmanic, Advaitic, and middle-class aesthetic being cultivated at her temples. If anything, it coexists harmoniously, and so Jogaṇī Mātā exemplifies how “tantrification”, as

Lutgendorf (

2001,

2007) terms it, has operated alongside and in conversation with the processes of upward mobility discussed above. Much as Lutgendorf has argued is the case with Hanuman throughout North India, Jogaṇī exemplifies a positive tantra that satisfies a middle-class need for “quick-fix” solutions in a frenzied modern marketplace, providing fast access to esoteric power. This esoteric aspect is neither off-putting nor transgressive to middle-class and upwardly mobile tastes so long as it presents itself in the context of a respectable form of religiosity, which Chinnamastā, among other Sanskritic signifiers, appears to provide. As R. Mahalakshmi contends regarding Chinnamastā at the Rajrappa site in Jharkhand, the tantric tradition of the Mahāvidyās offers a broader framework within which a local form of worship can be assimilated into the Brahmanical tradition, and this seems to apply to the Jogaṇī Mātā sites in Gujarat (

Mahalakshmi 2014, p. 213). By taking on the image of Chinnamastā, Jogaṇī participates in a non-threatening,

sāttvik tantrism which, whether explicitly identified by her affiliates or not, is satisfactorily removed from black tantrism and the interference of the

bhuvā. In this light, it does not preclude middle-class involvement. If anything, the rapid material benefits of

sāttvik tantrism make the ambitions of the ascending classes more eminently attainable. It is not, however, merely

what is sought after in these rites that is so crucial to class mobility, but perhaps more importantly

how it is asked for. Tantric imagery and efficacy, it would appear, when present in a certain measure alongside both familiar folk/village and Sanskritic/Brahmanical elements, can be part of a religious experience that is safe and even self-affirming for the middle-class and upwardly mobile. In short, “white” tantra dovetails with other perceived signifiers of status, such as the Sanskritic/Vaiṣṇavic, the universal and the gentrified. Jogaṇī’s popularity may also reflect just how influential Madhu Khanna’s “

bazaari tantra” has become in contemporary India. That is to say, with tantric imagery circulating so pervasively in popular culture by way of mass-mediated cultural products, its visibility and influence has become almost second nature, given how intuitively compatible it is with middle-class tastes and aspirations. This form of consumer-friendly tantra is sufficiently mainstream, and so it does not hinder the mainstream appeal of a goddess. Certainly, for individuals at the sites I visited, tantra appears to play a part in the performance of realizing and reiterating class status.

These speculations aside, countless urban and rural Jogaṇī Mātā sites demonstrate just how ubiquitous a variation of Chinnamastā imagery has become within Gujarati religious and visual space.

Kinsley (

1997) and

Benard (

1994) have each characterized Chinnamastā as one of the least worshipped Mahāvidyās, though the literally hundreds of examples of her image throughout Gujarat should prompt some re-evaluation of this claim. While Jogaṇī is not simply Chinnamastā, as many of the people I spoke with confirmed, the image of the severed-headed goddess may be closer to the everyday lives of worshippers than was once assumed.