Ultrafine Bubble Water for Crop Stress Management in Plant Protection Practices: Property, Generation, Application, and Future Direction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Properties and Generation of UFW

2.1. Bubble Classification and Definition

2.2. Ultrafine Bubble Water (UFW) Properties

- (1)

- Large specific surface area [23]

| Physicochemical Properties | Phenomenon | Theoretical Foundation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Large specific surface area | The large specific surface area gives the bubble a natural tendency to coalesce or dissolve. | The specific surface area refers to the ratio of its total surface area to the volume of the gas it contains. | [23] |

| 2 | Slow rising velocity in water | The UFBs can remain suspended in water for extended periods and have a relatively long residence time. | Using Stokes’ law, where the rising velocity is proportional to its size and inversely proportional to the viscosity of the surrounding liquid. | [23,30] |

| 3 | Easy self-pressurization and high gas dissolution rate | During self-pressurization, the gas in the bubble continuously dissolves into the liquid, resulting in the shrinkage and disappearance of nanobubbles. | Based on Young–Laplace equation, the pressure is directly proportional to the gas–liquid interface tension and inversely proportional to the bubble diameter. | [24,29,31] |

| 4 | Strong mass transfer efficiency | The mass transfer efficiency is significantly higher than that of conventional bubbles to make the UFBs spread over a larger region and reach confined spaces easily. | Based on mass transfer coefficient formula and transfer flux formula, larger contact surface area, lower surface tension, massive quantities, and long-term interaction with liquid result in higher mass transfer efficiency. | [14,23,32] |

| 5 | Strong interfacial Zeta potential | When the Zeta potential is high, the electrostatic repulsion between the UFBs is strong, which can prevent bubbles from approaching and coalescing, thereby improving the stability of UFB water. | According to electrostatic laws and Poisson–Boltzmann equation, bubbles with charge interfaces generate an electrical field that preferentially attracts the opposite charge ions distributed in solutions. | [14,23,29,33] |

| 6 | Generating hydroxyl radicals with strong oxidation | Hydroxyl radicals can oxidize the surface-active substances on the surface of UFBs, reducing the surface activity and stability of UFBs. | Oxidation-reduction potential measures the ability of an aqueous solution to oxidize or reduce another substance, and it changes linearly with logarithmic change in O2 concentration. | [25,34] |

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

2.3. Generation of UFB Water and Ozone UFB Water

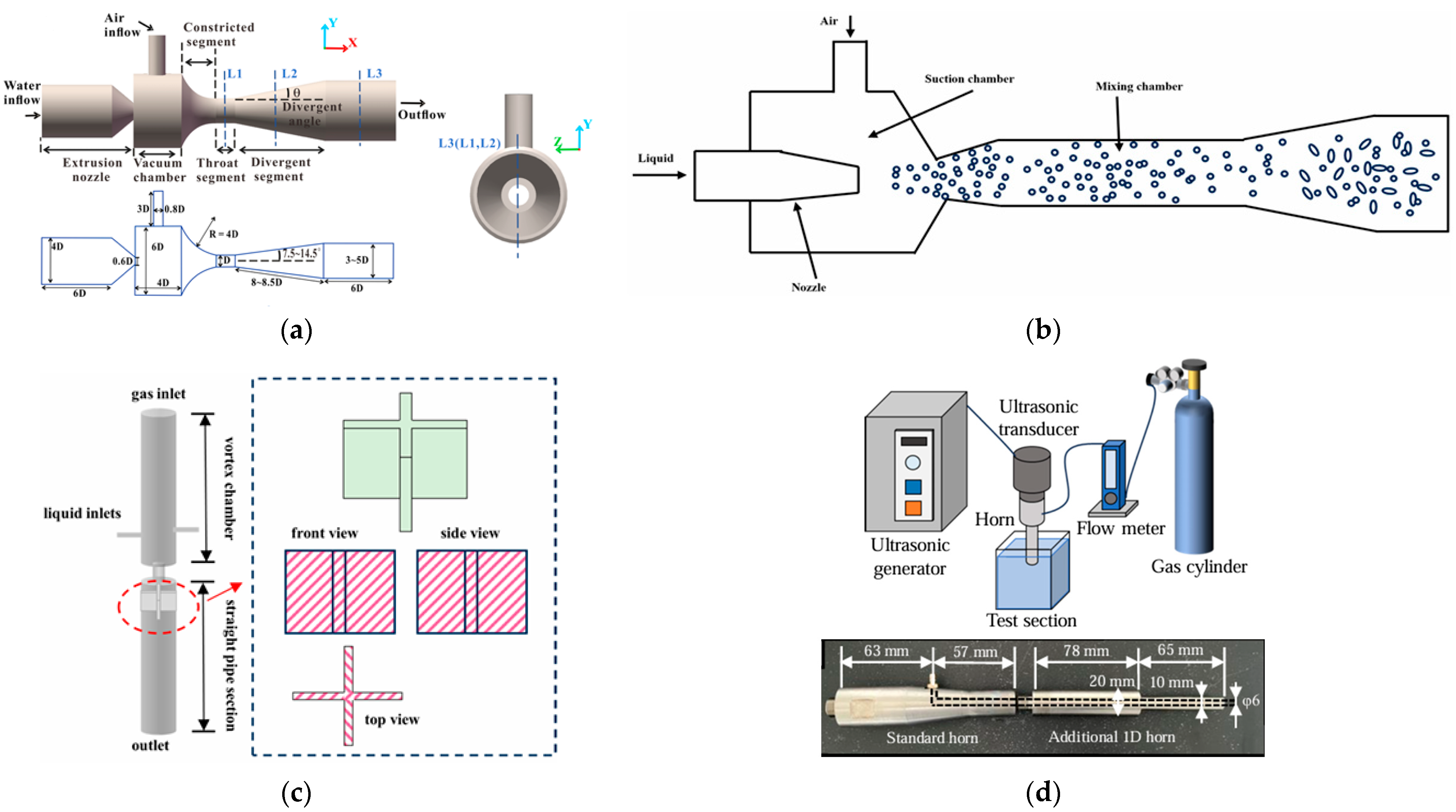

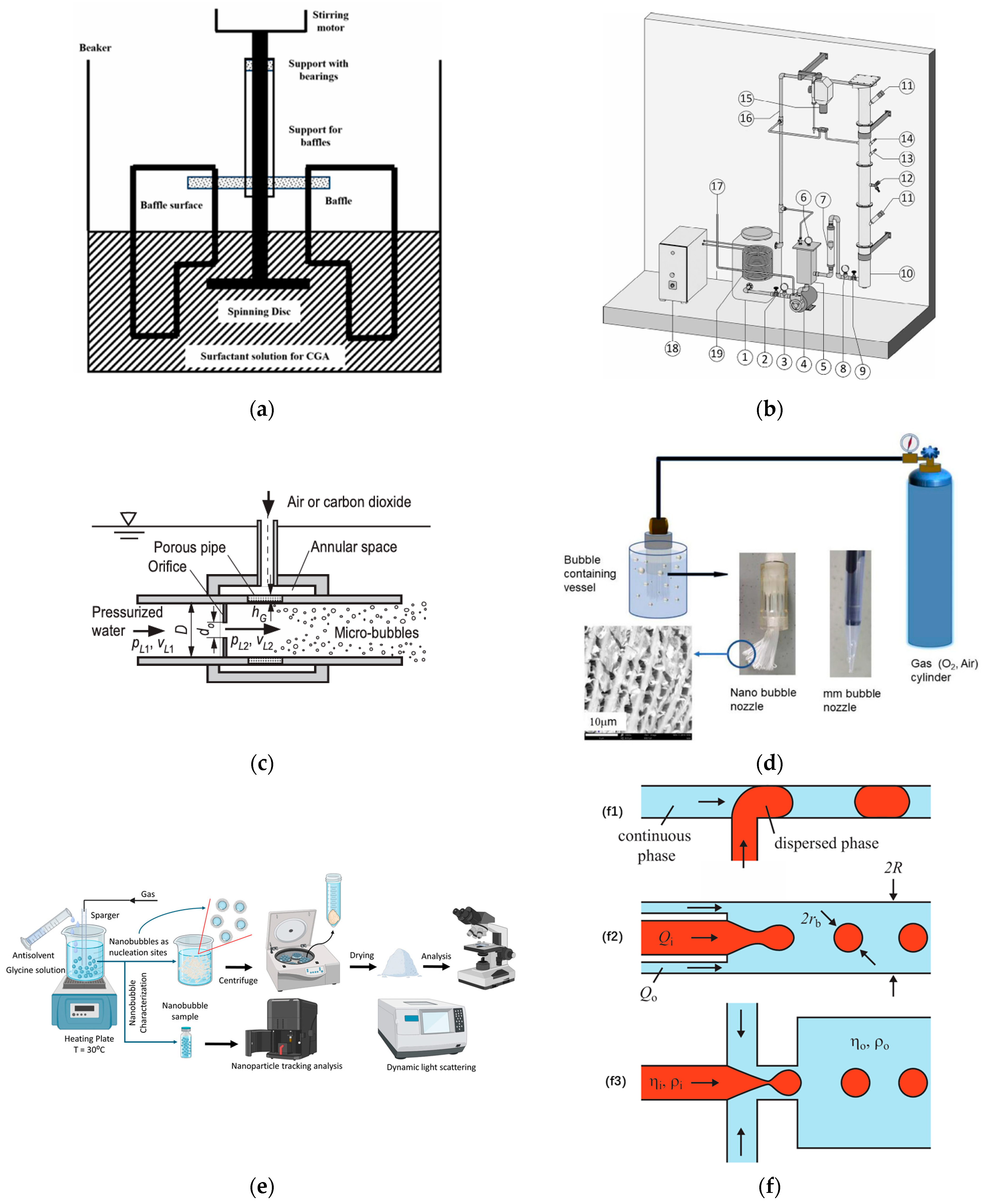

2.3.1. UFB Water Generation

- (1)

- Physical methods

- ①

- Cavitation approaches

- ②

- Gas dispersion approaches

- ③

- Solvent exchange approach

- ④

- Temperature alteration approach

- ⑤

- Electrohydrodynamic effect approach

- ⑥

- Pressurized gas dissolution approach

- (2)

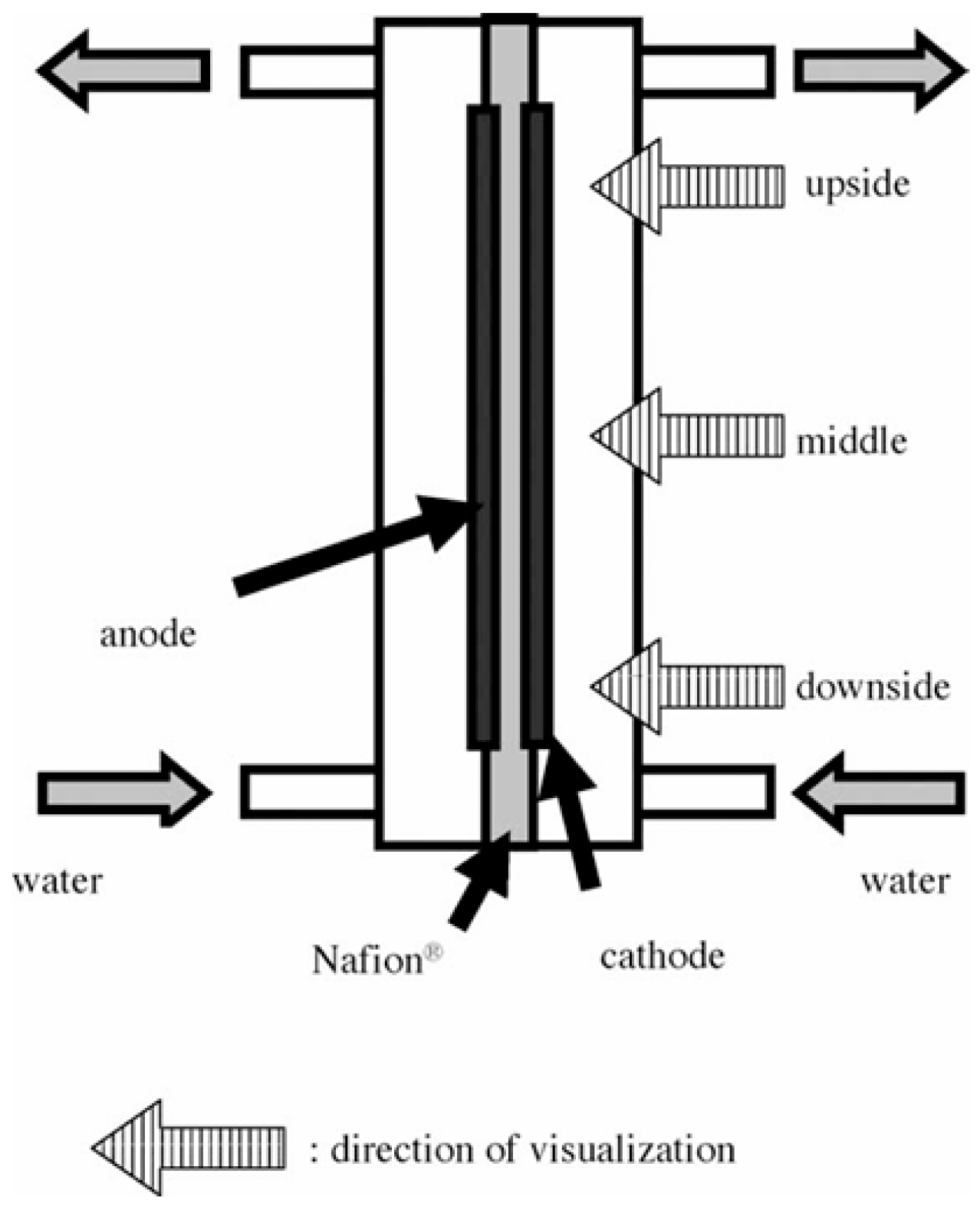

- Chemical methods

- ①

- Photocatalysis technology

- ②

- Electrochemical (electrolysis) approach

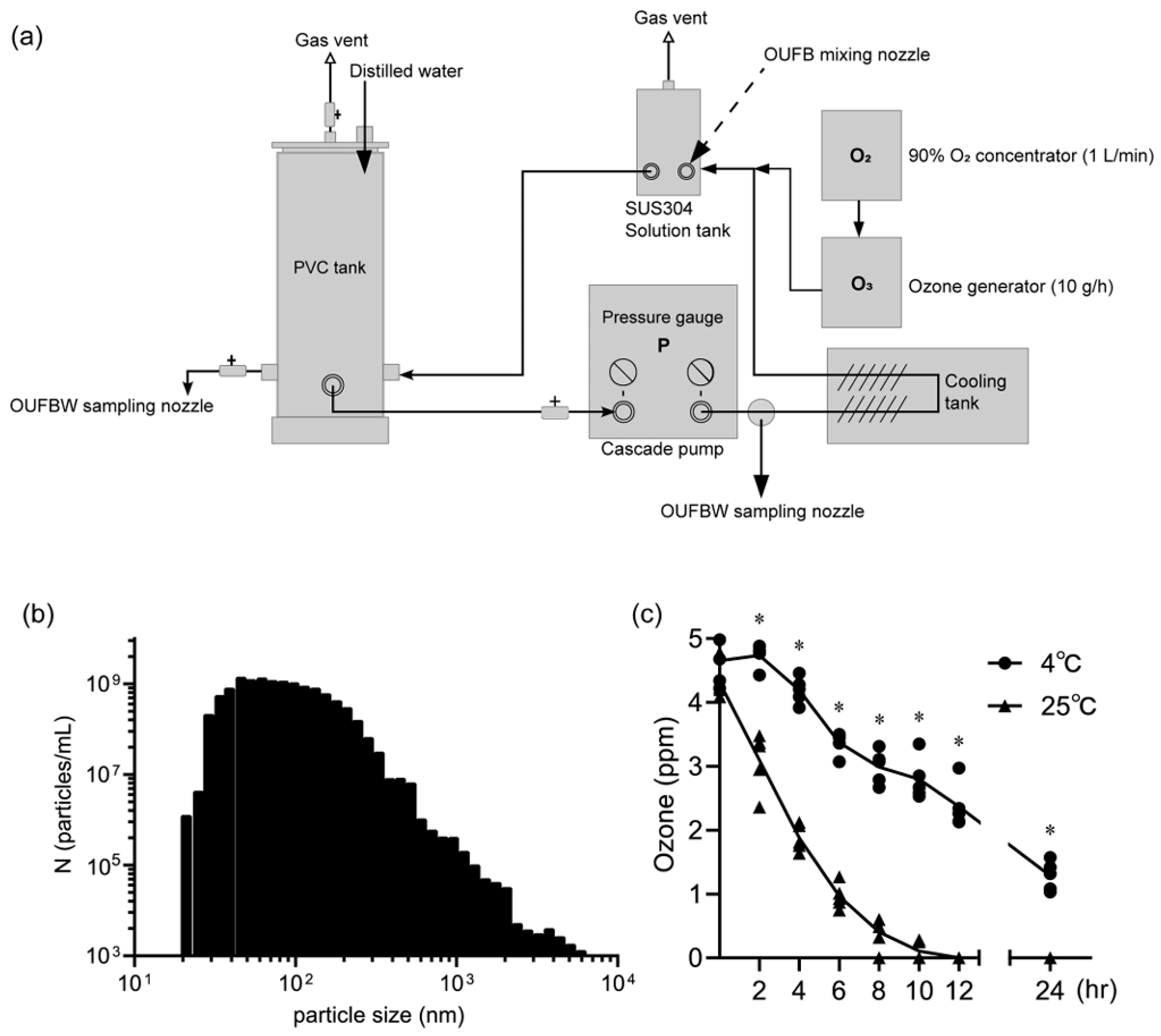

2.3.2. Ozone UFB Water Generation

3. Controlling Biotic Stresses of Crop Pests and Diseases Using UFW

3.1. Plant Pests Control Using UFW

3.2. Plant Diseases Control Using UFW

3.2.1. Function of UFB Water for Controlling Crop Diseases

- (1)

- Reducing and eliminating harmful pathogens.

- (2)

- Breaking down biofilms.

- (3)

- Strengthening plant immunity and health.

- (4)

- Reducing plant disease infestations.

3.2.2. UFB Water to Control Crop Diseases

- (1)

- Controlling soilborne plant diseases.

- (2)

- Controlling airborne plant diseases.

- (3)

- Controlling waterborne plant diseases and solving root rot of hydroponic vegetables.

- (4)

- Treatment of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables.

4. UFB Water Against Abiotic Stresses of Crops

4.1. UFW on Plant Growth Under Salt Stress

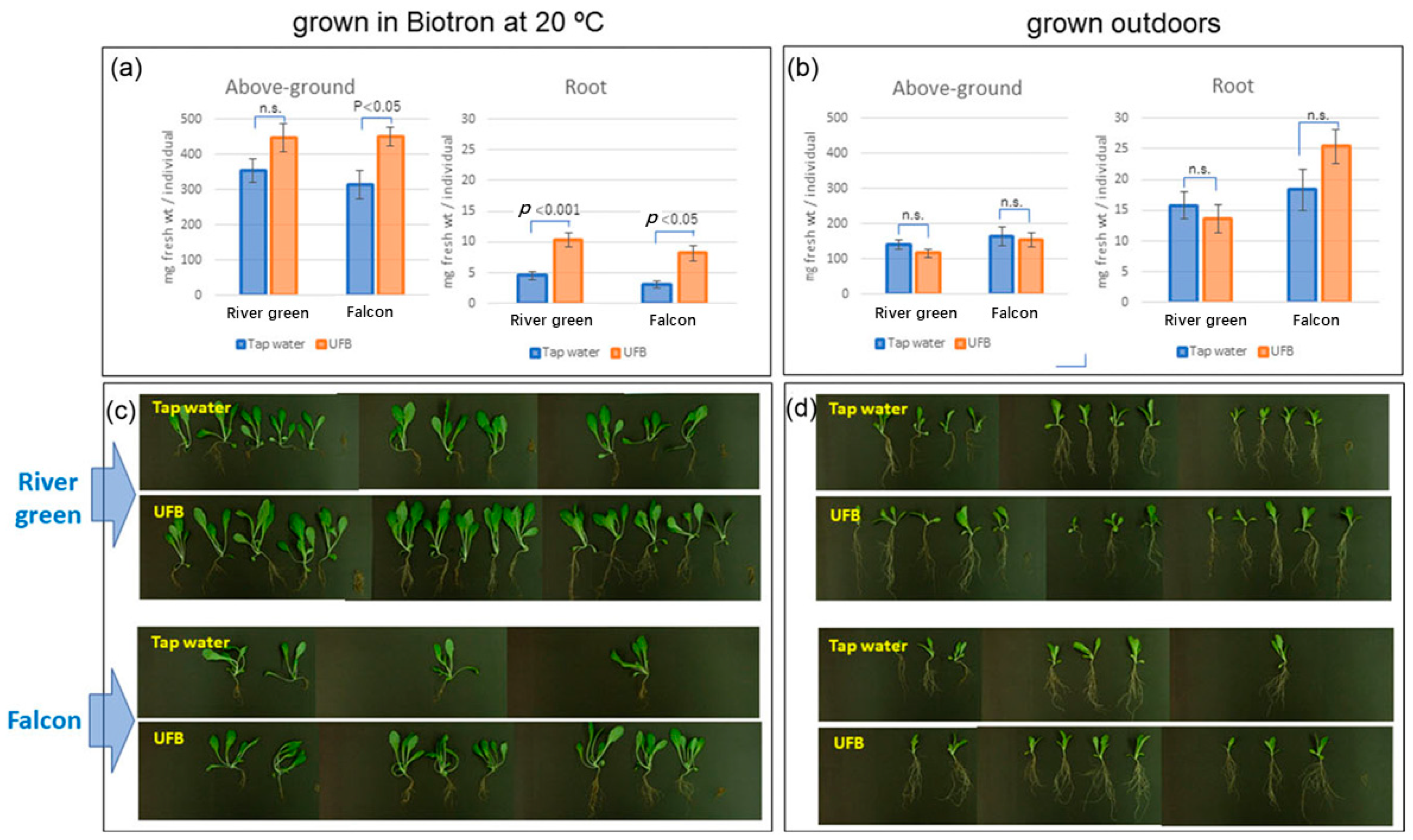

4.2. UFW Improves Plant Growth in Damaged Soil

4.3. UFW on Plant Growth Under Drought Stress

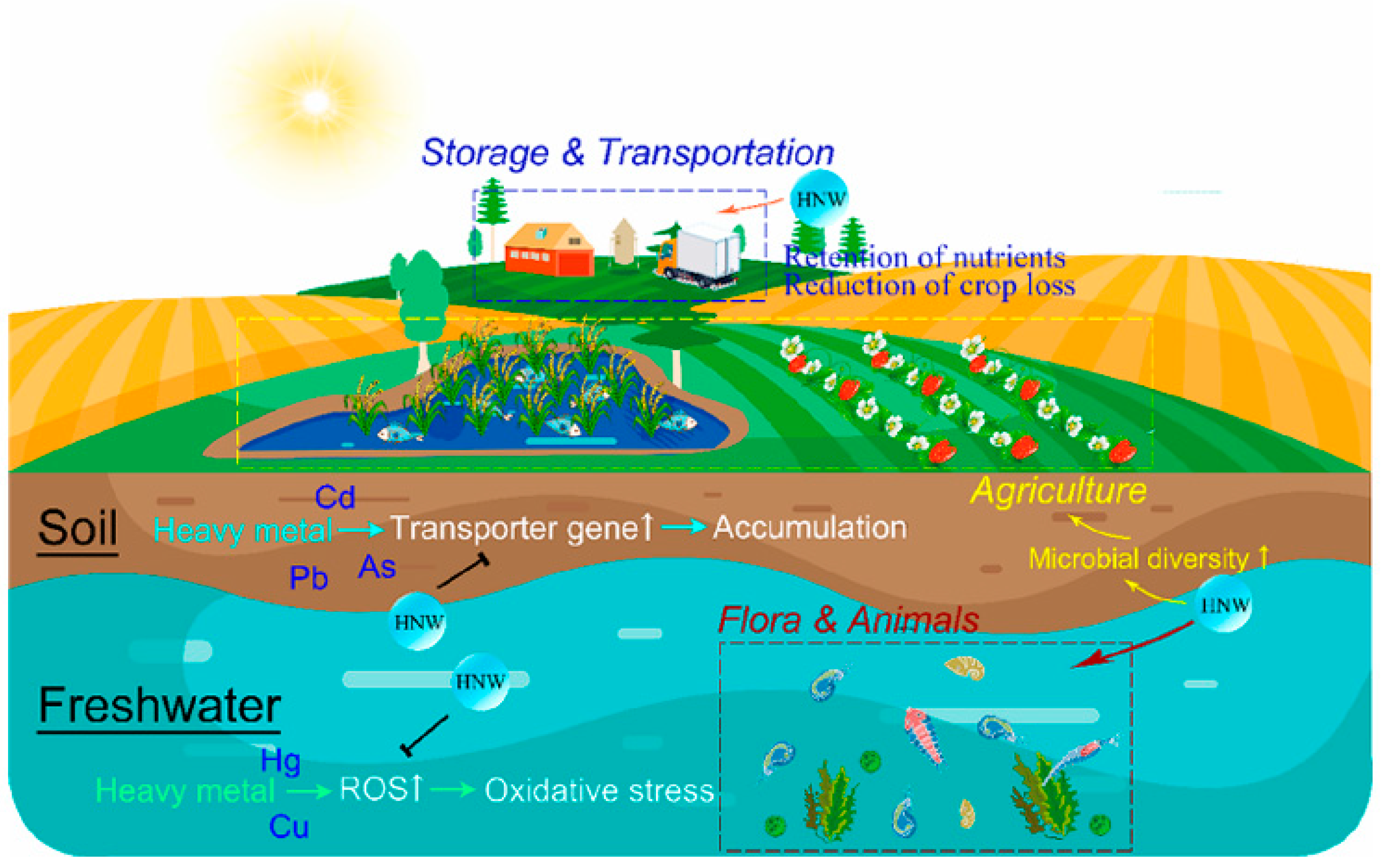

4.4. Hydrogen Nanobubble Water on Removing Heavy Metal Stress

5. Summary, Conflict, and Prospects

5.1. Summary

5.2. Conflicts

5.3. Prospects

5.3.1. Mechanism of UFW Controlling Plant Pests and Diseases

5.3.2. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying UFW’s Effects on Pest Resistance

5.3.3. Hydrophilic Nanopatterned Surfaces of Targeted Crops

5.3.4. Application of Activated UFB Water in Plant Protection Practices

5.3.5. Integrated Intelligent Plant Cultivation System

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UFB | Ultrafine Bubble |

| UFW | Ultrafine Bubble Water |

| OUFBW | Ozone Ultrafine Bubble Water |

| MNB | Micro-nanobubble |

| NB | Nanobubble |

References

- Du, B.; Haensch, R.; Alfarraj, S.; Rennenberg, H. Strategies of plants to overcome abiotic and biotic stresses. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, Y. A Review: Development of Plant Protection Methods and Advances in Pesticide Application Technology in Agro-Forestry Production. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S. FAO Report Reveals Shocking Crop Losses-Up to 40% Due to Pests and Diseases Annually.pdf. Available online: https://krishijagran.com/agriculture-world/fao-report-reveals-shocking-crop-losses-up-to-40-due-to-pests-and-diseases-annually/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Sarkozi, A. New Standards to Curb the Global Spread of Plant Pests and Diseases.pdf. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/New-standards-to-curb-the-global-spread-of-plant-pests-and-diseases/en (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- FAO. Pesticides Use and Trade. 1990–2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/highlights-archive/highlights-detail/pesticides-use-and-trade-1990-2023/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- FAO. Guidelines on Prevention and Management of Pesticide Resistance.pdf. 2012. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/Pests_Pesticides/Code/FAO_RMG_Sept_12.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Elumalai, P.; Gao, X.; Parthipan, P.; Luo, J.; Cui, J. Agrochemical pollution: A serious threat to environmental health. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 43, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pest and Pesticide Management. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/pest-and-pesticide-management/news/detail/en/c/1737648 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Hung, J.-C.; Li, N.-J.; Peng, C.-Y.; Yang, C.-C.; Ko, S.-S. Safe Farming: Ultrafine Bubble Water Reduces Insect Infestation and Improves Melon Yield and Quality. Plants 2024, 13, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Xu, F.; Muhammad, T.; Li, Y. Appropriate dissolved oxygen concentration and application stage of micro-nano bubble water oxygation in greenhouse crop plantation. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 223, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhai, G.; Lv, M.; Deng, Z.; Zong, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Application and Prospect of Micro-nano Bubble in Agriculture Irrigation Areas. J. Irrig. Drain. 2016, 35, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, O.A.L.; dos Santos, M.S.; Antunes Filho, S.; Backx, B.P. Nanotechnology for the control of plant pathogens and pests. Plant Nano Biol. 2024, 8, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, G.; Musharraf, S.T.; Deepak, V.B. Review on nanobubbles behavior with hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2023, 33, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Chen, S.; Su, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B.; Sun, H. A review and perspective on micro and nanobubbles: What They Are and Why They Matter. Miner. Eng. 2022, 189, 107906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Role of Nanobubbles in Pest and Disease Control. Available online: https://divaenvitec.com/the-role-of-nanobubbles-in-pest-and-disease-control/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Huang, Q.; Liu, A.R.; Zhang, L.J. Characteristics of micro-nanobubbles and their applications in soil environment improvement. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2022, 12, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Iijima, M.; Yamashita, K.; Hirooka, Y.; Ueda, Y.; Yamane, K.; Kamimura, C. Promotive or suppressive effects of ultrafine bubbles on crop growth depended on bubble concentration and crop species. Plant Prod. Sci. 2021, 25, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Dai, H.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, W.; Hu, Z.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W. Nanobubbles promote nutrient utilization and plant growth in rice by upregulating nutrient uptake genes and stimulating growth hormone production. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 800, 149627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.F.; Chen, J.; Shao, C.H.; Guan, X.J.; Qiu, C.F.; Chen, X.M.; Liang, X.H.; Xie, J.; Deng, G.Q.; Peng, C.R. Effect of micro-nano bubbles on the yield of different rice types. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Zhao, T.; Kanematsu, W.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, T.; Ohyama, A.; Nakano, A.; Higashide, T. Application of a Growth Model to Validate the Effects of an Ultrafine-bubble Nutrient Solution on Dry Matter Production and Elongation of Tomato Seedlings. Hortic. J. 2019, 88, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO-20480-1-2017; Fine Bubble Technology—General Principles for Usage and Measurement of Fine Bubbles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Jia, M.; Farid, M.U.; Kharraz, J.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Chopra, S.S.; Jang, A.; Chew, J.; Khanal, S.K.; Chen, G.; An, A.K. Nanobubbles in water and wastewater treatment systems: Small bubbles making big difference. Water Res. 2023, 245, 120613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Advances in the Research on the Properties and Applications of Micro-Nano Bubbles. Processes 2025, 13, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, P.; Ning, R.; Ratul, R.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Mechanisms on stability of bulk nanobubble and relevant applications: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Chiba, K.; Li, P. Free radical generation from collapsing microbubbles in the absence of a dynamic stimulus. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Nab, A.K.; Morad, A.M.; Selima, E.S.; Kanagawa, T.; Abu-Bakr, A.F. A review of microcavitation bubbles dynamics in biological systems and their mechanical applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 121, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M. Base and technological application of micro-bubble and nanobubble. Mater. Integr. 2009, 22, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Temesgen, T.; Bui, T.T.; Han, M.; Kim, T.-I.; Park, H. Micro and nanobubble technologies as a new horizon for water-treatment techniques: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 246, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, T.; Yaparatne, S.; Graf, J.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Apul, O. Electrostatic forces and higher order curvature terms of Young–Laplace equation on nanobubble stability in water. npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.; Mohamed, M.M.; Maraqa, M.A.; Hamouda, M.A.; Hassan, A.A.; Ali, J.; Jung, J. A critical review of the recent developments in micro–nano bubbles applications for domestic and industrial wastewater treatment. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 6591–6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Kawamura, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ohnari, H.; Himuro, S.; Shakutsui, H. Effect of shrinking microbubble on gas hydrate formation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 2171–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Tanaka, K. Nano bubble—Size dependence of surface tension and inside pressure. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2008, 40, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. ζ potential of microbubbles in aqueous solutions electrical properties of the gas water interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 21858–21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malahlela, H.K.; Belay, Z.A.; Mphahlele, R.R.; Caleb, O.J. Micro-Nano bubble water technology: Sustainable solution for the postharvest quality and safety management of fresh fruits and vegetables—A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 94, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lu, X.; Tao, S.; Ren, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, B. Preparation and Properties of CO2 Micro-Nanobubble Water Based on Response Surface Methodology. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, H.; Pan, H.; Jiang, L.; Su, W.-H.; Chen, Q.; Tang, Y.; Pan, J.; Yu, K. Full life circle of micro-nano bubbles: Generation, characterization and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Generation and stability of bulk nanobubbles: A review and perspective. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 53, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z. Research on the Stability of Nanobubbles and the Mechanism and Application of Hydroxyl Radicals Generation. Ph.D. Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Z.J.; Agblevor, F.A. Microbubble fermentation of recombinant Pichia pastoris for human serum albumin production. Process. Biochem. 2005, 40, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchepare, R.; Oliveira, H.; Nicknig, M.; Azevedo, A.; Rubio, J. Nanobubbles: Generation using a multiphase pump, properties and features in flotation. Miner. Eng. 2017, 112, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Saihara, Y.; Ogumi, Z. Bubble visualization and electrolyte dependency of dissolving hydrogen in electrolyzed water using Solid-Polymer-Electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 50, 5229–52366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, W.F.; Kistler, K.C.; Olmeda, C.C.; Sen, A.; Angelo, S.K.S.; Cao, Y.; Mallouk, T.E.; Lammert, A.P.E.; Crespi, V.H. Catalytic Nanomotors: Autonomous Movement of Striped Nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13424–13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cui, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; He, L.; Fan, W.; Huo, M. Parametric analysis of venturi-type microbubble generator and the bubble fragmentation dynamics. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, W.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. Comparison of bubble velocity, size, and holdup distribution between single- and double-air inlet in jet microbubble generator. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 16, e2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Song, X. Experimental and numerical study on the bubble dynamics and flow field of a swirl flow microbubble generator with baffle internals. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 263, 118066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuki, N.; Murakami, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Xing, W.; Makuta, T. Microbubble Generation by Hollow Ultrasonic Horn Using Longitudinal and Torsional Complex Oscillation. Adv. Exp. Mech. 2024, 9, 24-0014. [Google Scholar]

- Yasui, K. Acoustic Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. In Springer Briefs in Molecular Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-68236-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sadatomi, M.; Kawahara, A.; Matsuura, H.; Shikatani, S. Micro-bubble generation rate and bubble dissolution rate into water by a simple multi-fluid mixer with orifice and porous tube. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2012, 41, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sai, K.P.; Nirmalkar, N. Bulk nanobubbles as active nucleation sites during antisovent crystallization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 309, 121464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoeve, W.; Dollet, B.; Gordillo, J.M.; Versluis, M.; van Wijngaarden, L.; Lohse, D. Bubble size prediction in co-flowing streams. EPL Europhys. Lett. 2011, 94, 64001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qiu, L.; Liu, G. Basic characteristics and application of micro-nano bubbles in water treatment. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Zou, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Formation and Stability of Bulk Nanobubbles Generated by Ethanol–Water Exchange. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scienceinsights. How Does Temperature Affect Oxygen Concentrations? Available online: https://scienceinsights.org/how-does-temperature-affect-oxygen-concentrations/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kurumanghat, V.; Sharma, H.; Nirmalkar, N.; Kabiraj, L. Experimental studies on the effect of bulk nanobubbles on the combustion of Jet A-1. Fuel 2025, 398, 135385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Yu, K.; Wang, D.; Yongphet, P.; Xu, H.; Yao, J. Experimental investigation on bubble coalescence regimes under non-uniform electric field. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 127982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyzas, G.Z.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Matis, K.A. From Microbubbles to Nanobubbles: Effect on Flotation. Processes 2021, 9, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.X.; Cui, Y.Z.; Li, C.X.; Shi, X.G.; Gao, J.S.; Lan, X.Y. Research and Application Process of Microbubble Generator. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2024, 43, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronico, P.; Paciolla, C.; Sasanelli, N.; De Leonardis, S.; Melillo, M.T. Ozonated water reduces susceptibility in tomato plants to Meloidogyne incognita by the modulation of the antioxidant system. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 18, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigigallo, M.I.; Melillo, M.T.; Bubici, G.; I Dobrev, P.; Vankova, R.; Cillo, F.; Veronico, P. Ozone treatments activate defence responses against Meloidogyne incognita and Tomato spotted wilt virus in tomato. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2251–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratling, W.T.; Jespersen, D.; Waltz, C.; Martinez-Espinoza, A.D.; Bahri, B.A. Evaluation of oxygenated and ozonated nanobubble water treatments for dollar spot suppression in seashore paspalum. Agron. J. 2024, 117, e21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

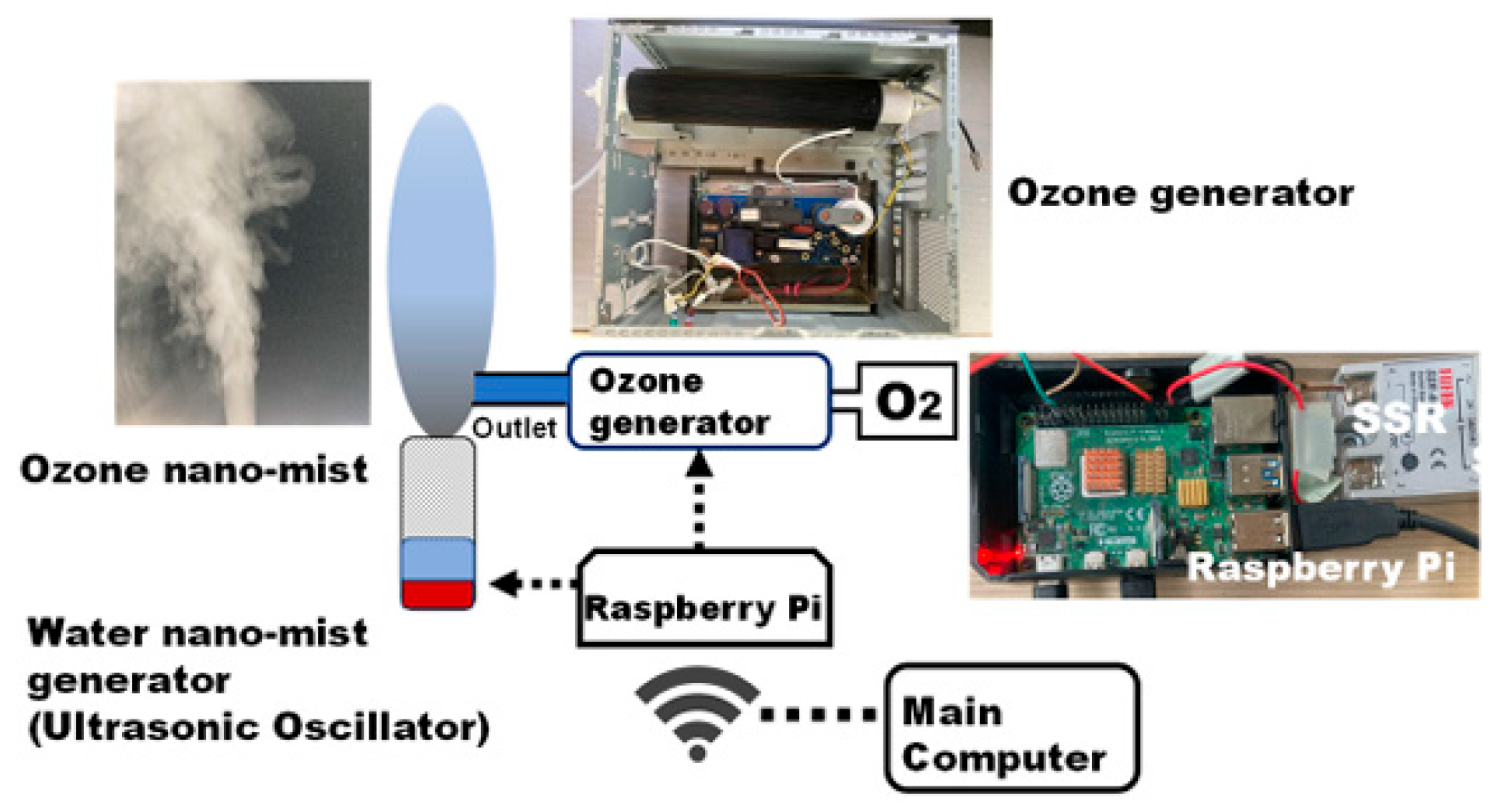

- Ebihara, K.; Mitsugi, F.; Aoqui, S.I.; Yamashita, Y.; Baba, S. Ozone nano-mist disinfection of insect pests and automatic spraying system based on deep learning technology. Int. J. Plasma Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, e02003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.-C.; Peng, L.; Jing, Z.-B.; Wang, W.-L.; Cai, H.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-Q.; Li, L.-D.; Ye, B.; Wu, Q.-Y. Superior water disinfection via ozone micro-bubble aeration: Performance and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takizawa, F.; Domon, H.; Hiyoshi, T.; Tamura, H.; Shimizu, K.; Maekawa, T.; Tabeta, K.; Ushida, A.; Terao, Y. Ozone ultrafine bubble water exhibits bactericidal activity against pathogenic bacteria in the oral cavity and upper airway and disinfects contaminated healthcare equipment. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seridou, P.; Kalogerakis, N. Disinfection applications of ozone micro- and nanobubbles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 3493–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Ye, H.; Hao, G.; Du, F.; Wang, P. A supramolecular bactericidal material for preventing and treating plant-associated biofilms. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Staskawicz, B.J.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system: From discovery to deployment. Cell 2024, 187, 2095–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arablousabet, Y.; Povilaitis, A. The Impact of Nanobubble Gases in Enhancing Soil Moisture, Nutrient Uptake Efficiency and Plant Growth: A Review. Water 2024, 16, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

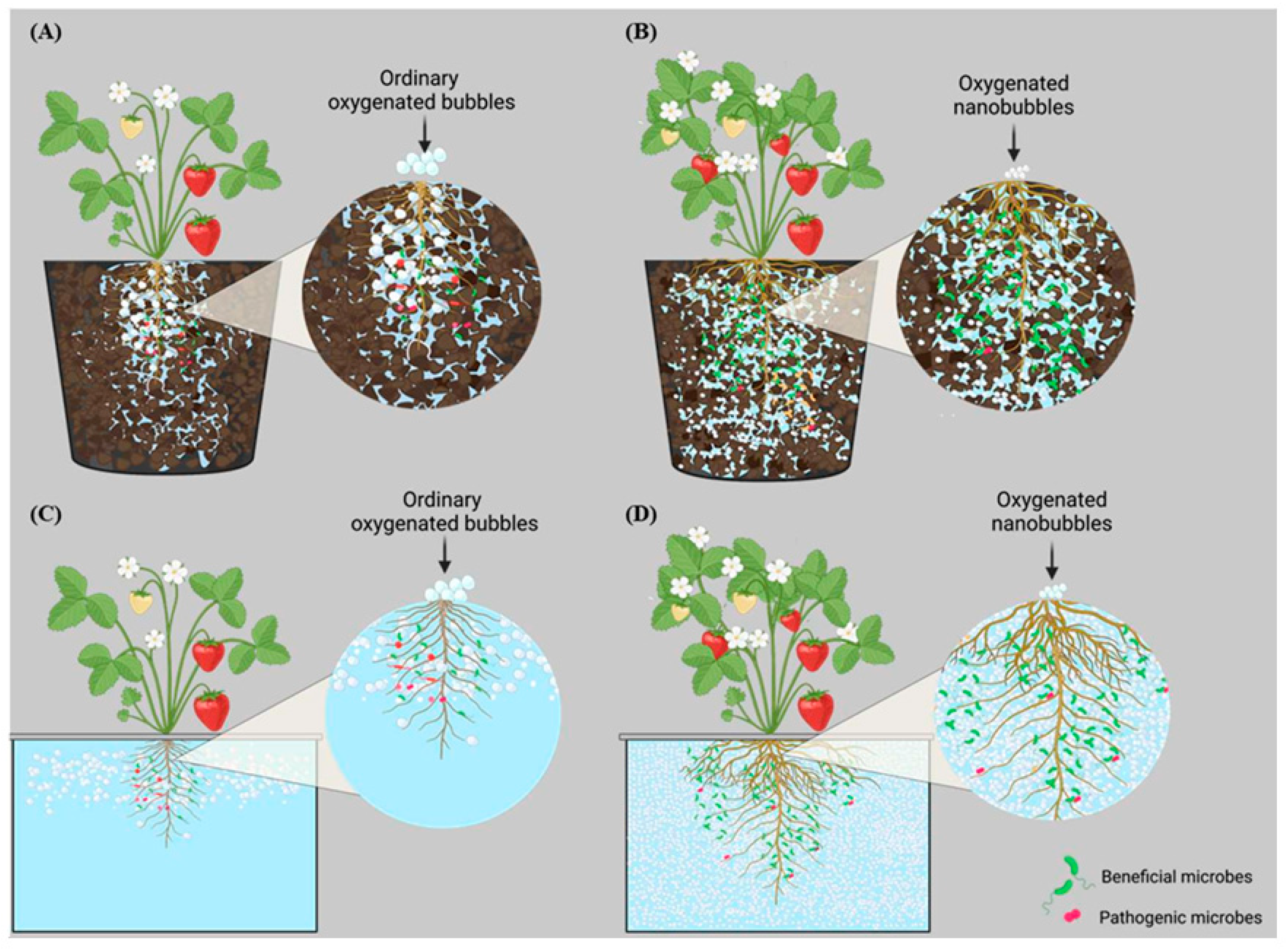

- Mamun, M.A.; Islam, T. Oxygenated Nanobubbles as a Sustainable Strategy to Strengthen Plant Health in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Kumari, A.; Mahanta, M.; Upamanya, G.K.; Heisnam, P.; Borua, S.; Kaman, P.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Mallik, M.; Muthukrishnan, G.; et al. Nanotechnological approaches for management of soil-borne plant pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.F.; Liu, J.S.; Jin, W.M. Effects of atmospheric ozone on anthocyanin and carotenoid of plants. Plant Physiol. J. 2017, 53, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.T.; Sun, G.M.; Liu, F.; Zhou, L.G.; Wang, F.L. Ozone disinfection of three soilborne pathogens in nutrient solution. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2007, 23, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.L.; Lin, S.H.; Yang, W.H.; Zhang, H.J. Preparation of micro-nano bubble ozone water and its application on soil and matrix disinfection. Vegetables 2019, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- An, X.; Song, W.; He, H.; Qi, T. Disinfection Efficacy of Micro/nano Bubbles Ozone Water on F. oxysporum f. sp. Lycopeersici. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2014, 45, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Live to Plant. Exposure to Airborne Diseases in Plants: Identification and Control. Available online: https://livetoplant.com/exposure-to-airborne-diseases-in-plants-identification-and-control/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Van der Heyden, H.; Dutilleul, P.; Charron, J.B.; Bilodeau, G.J.; Carisse, O. Monitoring airborne inoculum for improved plant disease management. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.M.; Li, Y.F.; Geng, X.H.; An, X.C.; Song, W.T. On different ozone water generation systems and its spray characteristics. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2013, 44, 678–682. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; Song, W. Research on the Feasibility of Spraying Micro/Nano Bubble Ozonated Water for Airborne Disease Prevention. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2015, 37, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, J. How To Prevent & Control Waterborne Diseases in Hydroponic Systems. Available online: https://greenhouseemporium.com/prevent-waterborne-diseases-in-hydroponic-systems/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Suárez-Cáceres, G.P.; Pérez-Urrestarazu, L.; Avilés, M.; Borrero, C.; Eguíbar, J.R.L.; Fernández-Cabanás, V.M. Susceptibility to water-borne plant diseases of hydroponic vs. aquaponics systems. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

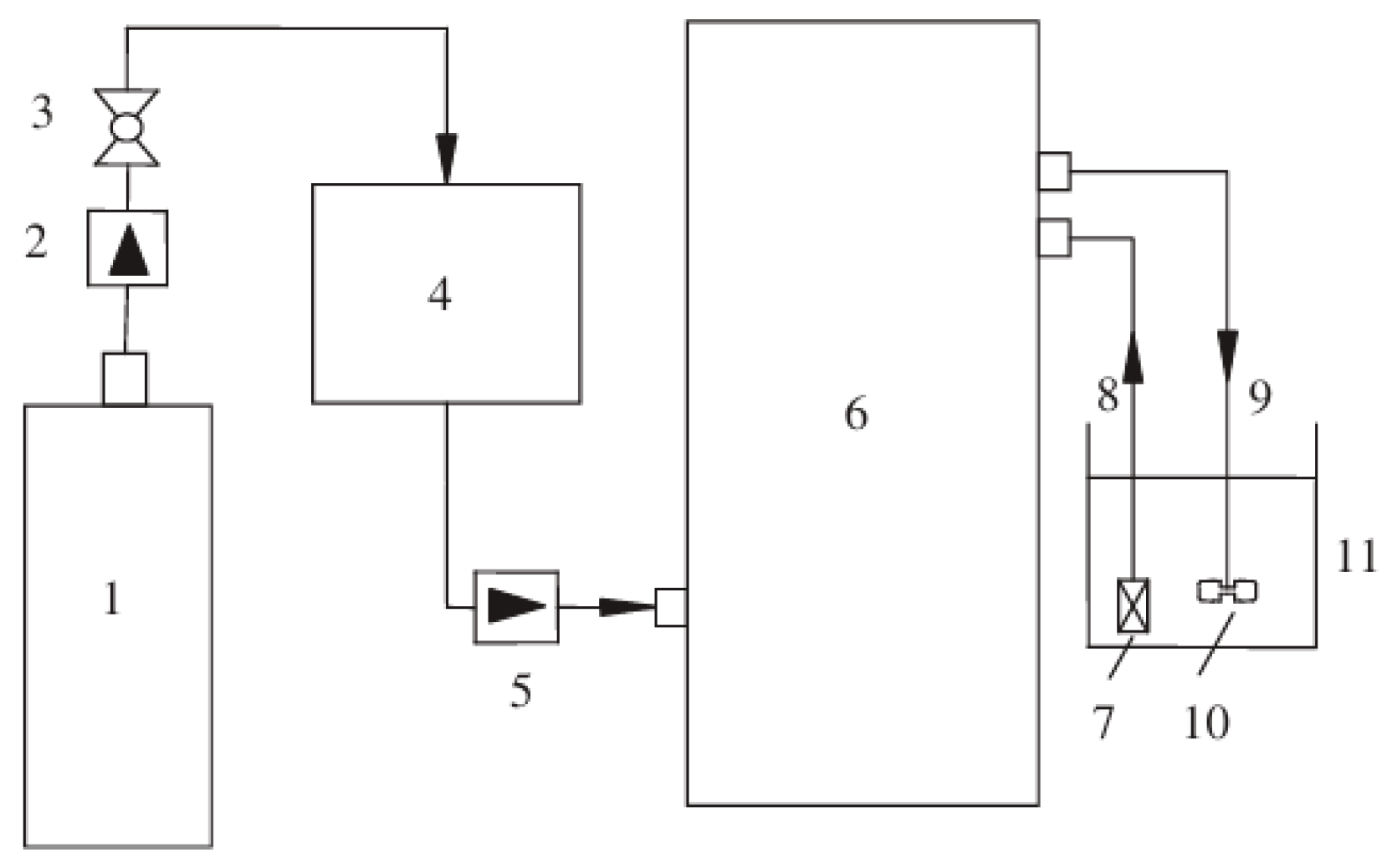

- Xue, X.; Yang, W.; Zhang, T. Micro/nano bubble aeration disinfection technology of nutrient solution. Agric. Eng. Technol. 2017, 37, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.P.; Xu, F.P.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, K.Y.; Wang, X.R.; Li, Y.K. Influence of micro bubble oxygen irrigation on vegetable growth and quality effect. J. Irrig. Drain. 2016, 35, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, N.; Yang, W.; Ren, Q.; Zhao, Y. Micro-Nano Bubble Generating Technology and its Application in Hydroponics with Aeration. Vegetables 2019, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

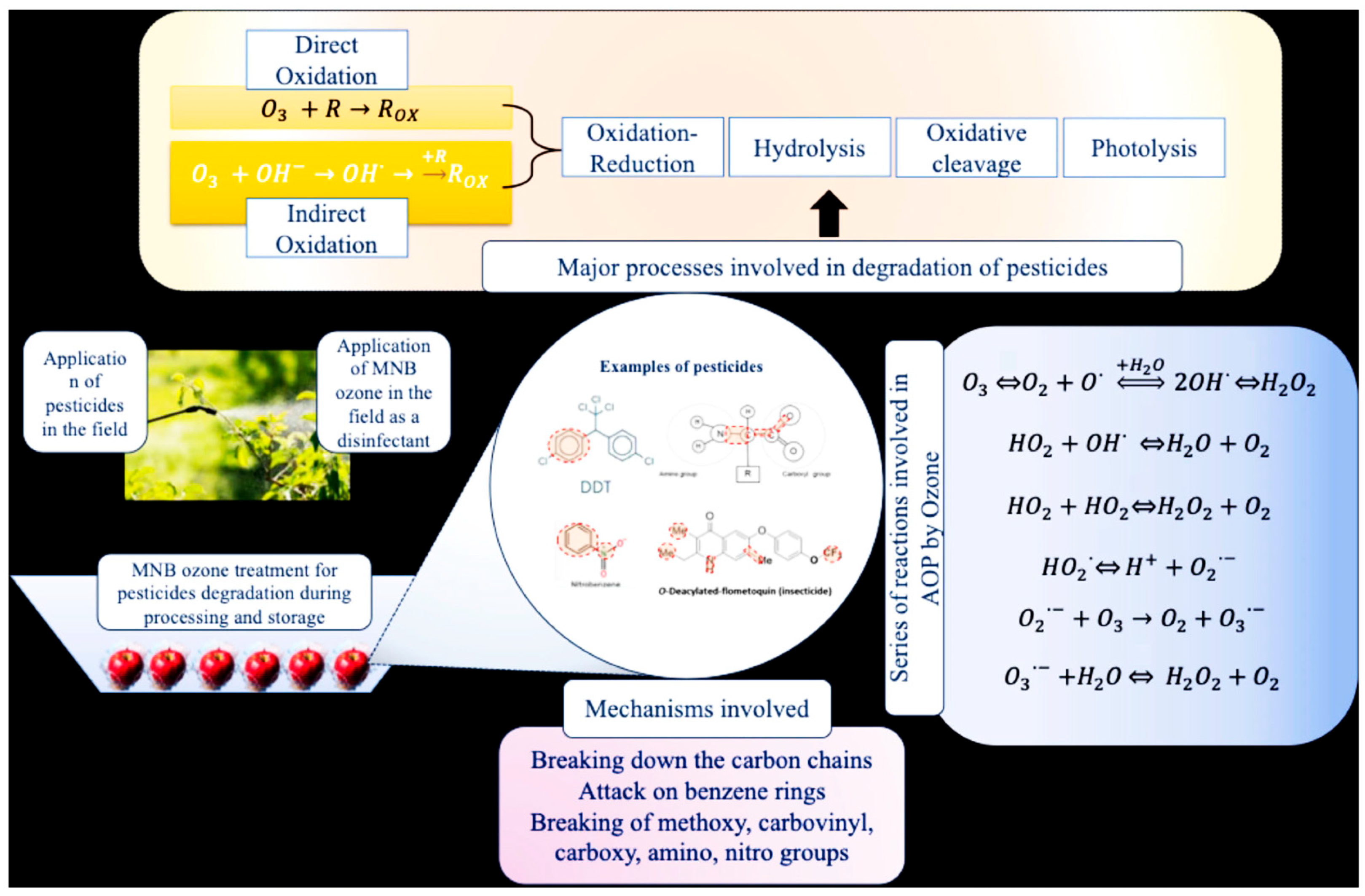

- Pal, P.; Kioka, A. Micro and nanobubbles enhanced ozonation technology: A synergistic approach for pesticides removal. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, G.A.; Devrajani, S.K.; Memon, S.A.; Qureshi, S.S.; Anbuchezhiyan, G.; Mubarak, N.M.; Shamshuddin, S.; Siddiqui, M.T.H. Holistic insight mechanism of ozone-based oxidation process for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2024, 359, 142303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Shen, C.; Geng, Z.; Wan, L. Study of new deep cleaning processing technology of fruits and vegetables. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 33, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Handique, B.; Kalita, P.; Das, S.; Devi, H.S. Potential of Nano-particles in Mitigating Abiotic Stress in Crops. Adv. Res. 2025, 26, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, R.; Li, G.; Zhou, B.; Cheng, P. Subsurface drip irrigation with micro-nano bubble hydrogen water improves the salt tolerance of lettuce by regulating the antioxidant system and soil bacterial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 207, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, M.; Yamashita, T.; Kaida, R.; Seo, S.; Tanaka, K.; Abe, S.; Nakano, M.; Fujii, Y.; Kuchitsu, K. Ultrafine bubble water mitigates plant growth in damaged soil. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 2466–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Motomura, M.; Iijima, M. Ultra-fine bubble irrigation promotes coffee (Coffea arabica) seedling growth under repeated drought stresses. Plant Prod. Sci. 2024, 27, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Teng, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, F. Hydrogen Nanobubble Water: A Good Assistant for Improving the Water Environment and Agricultural Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12369–12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, J.; Yuan, Q.; Liang, J.; He, Z.; Xie, P.; Zhou, H. Effects of Micro/nano Bubble Water on the Growth of Rice Seedlings under Salt Stress. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2022, 28, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Park, Y.-L.; Gutensohn, M. Glandular trichome-derived sesquiterpenes of wild tomato accessions (Solanum habrochaites) affect aphid performance and feeding behavior. Phytochemistry 2020, 180, 112532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Maeda, N.; Craig, V.S. Physical properties of nanobubbles on hydrophobic surfaces in water and aqueous solutions. Langmuir 2006, 22, 5025–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Gui, X.; Guo, H.; Cao, Y.; Xing, Y. Interfacial nanobubbles on different hydrophobic surfaces and their effect on the interaction of inter-particles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 582, 152184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M. Contact Angle Studies of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Surfaces. In Handbook of Magnetic Hybrid Nanoalloys and their Nanocomposites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Study on the Effect of Activated Water on the Growth of Different Crops and Edible Fungi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.; Oh, D.-H. Inactivation kinetics of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium on fresh-cut bell pepper treated with slightly acidic electrolyzed water combined with ultrasound and mild heat. Food Microbiol. 2016, 53, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, K.; Wang, X.; Lyu, C.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Inactivation of Yeast on Grapes by Plasma-Activated Water and Its Effects on Quality Attributes. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H. Effects of Plasma Active Water on Growth and Development of Non-Heading Cabbage. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ren, B.; Feng, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, P. Application progress of electrolytic water in plant protection in China. China Plant Prot. 2020, 1, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Adal, S.; Kıyak, B.D.; Koç, G.Ç.; Süfer, Ö.; Karabacak, A.Ö.; Çınkır, N.I.; Çelebi, Y.; Jeevarathinam, G.; Rustagi, S.; Pandiselvam, R. Applications of electrolyzed water in the food industry: A comprehensive review of its effects on food texture. Futur. Foods 2024, 9, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, H.; Kong, X.; Han, K.; Lei, J.; Zu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J. Deep learning-based weed detection for precision herbicide application in turf. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 3597–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Hu, G.; Tong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, J. Key Intelligent Pesticide Prescription Spraying Technologies for the Control of Pests, Diseases, and Weeds: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Ru, Y.; Fang, S.; Rong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yan, X.; Liu, M. Orchard variable rate spraying method and experimental study based on multidimensional prescription maps. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Typical Names | Size Ranges | Typical Objects 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrobubbles (MaB) (>100 µm) | Centimeter bubble (CMB) | >10 mm | Grape |

| Millimeter bubble (MMB) | 100 µm–10 mm | Most raindrops | |

| Microbubbles (MiB) (1 µm–100 µm) | Micron bubbles (MB) | <100 µm | Ordinary hair |

| Sub-microbubbles (SMB) | 1–10 µm | Erythrocyte | |

| Micro-nanobubbles (MNB) (<10 µm) | Ultrafine bubbles (UFB) | <1 µm | Cigarette smoke |

| Nanobubbles (NB) | <200 nm | Viruses |

| Methods | Generation Approaches | Mechanism | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Cavitation | Hydrodynamic | Using a localized low-pressure region to draw in gases and form UFBs | [36] |

| Acoustic | Using ultrasonic waves to cause gas nuclei in liquid for generating UFBs | [36] | ||

| Gas dispersion | Mechanical agitation | Using a rotating disk device to stir gas–liquid mixture at high speed | [38,39,40] | |

| Microporous structure | Applying micro-porous structures to disperse gas into UFBs when gas passes porous pipe | [35,36] | ||

| Microfluidic device | Narrowing main channel width and enhancing shear gradient to reduce bubble size | [36] | ||

| Solvent exchange | Replacing high gas solubility fluids with low gas solubility fluids | [36,37] | ||

| Temperature alteration | Altering temperature suddenly to provide sufficient energy, forming bubble nucleus | [36] | ||

| Electrohydrodynamic effect | Weakening gas–liquid interface tension leading to breakup of gas phase | [36] | ||

| Pressurized gas dissolution | Changing gas–liquid pressure to dissolve and release gases | [23,35] | ||

| Chemical | Electrolysis | Dissolving hydrogen in water through electrochemical reactions on electrode surface | [36,41] | |

| Photocatalysis technology | Catalyzing decomposition of hydrogen peroxide solution to produce UFBs | [42] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Ultrafine Bubble Water for Crop Stress Management in Plant Protection Practices: Property, Generation, Application, and Future Direction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232484

Zheng J, Xu Y, Liu D, Chen Y, Wang Y. Ultrafine Bubble Water for Crop Stress Management in Plant Protection Practices: Property, Generation, Application, and Future Direction. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232484

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Jiaqiang, Youlin Xu, Deyun Liu, Yiliang Chen, and Yu Wang. 2025. "Ultrafine Bubble Water for Crop Stress Management in Plant Protection Practices: Property, Generation, Application, and Future Direction" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232484

APA StyleZheng, J., Xu, Y., Liu, D., Chen, Y., & Wang, Y. (2025). Ultrafine Bubble Water for Crop Stress Management in Plant Protection Practices: Property, Generation, Application, and Future Direction. Agriculture, 15(23), 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232484