The Potential of Vitamin D-Regulated Intracellular Signaling Pathways as Targets for Myeloid Leukemia Therapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Signaling Pathways Studied in Hematopoietic and Myeloid Cells

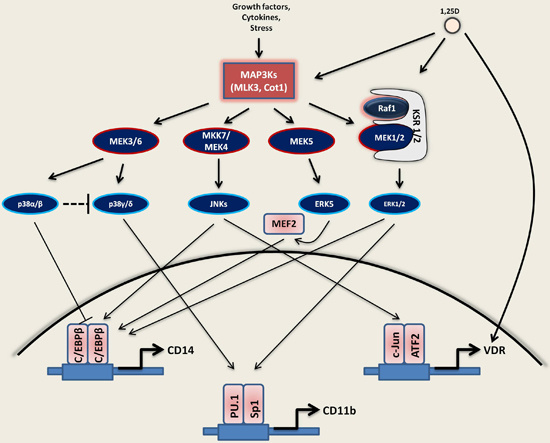

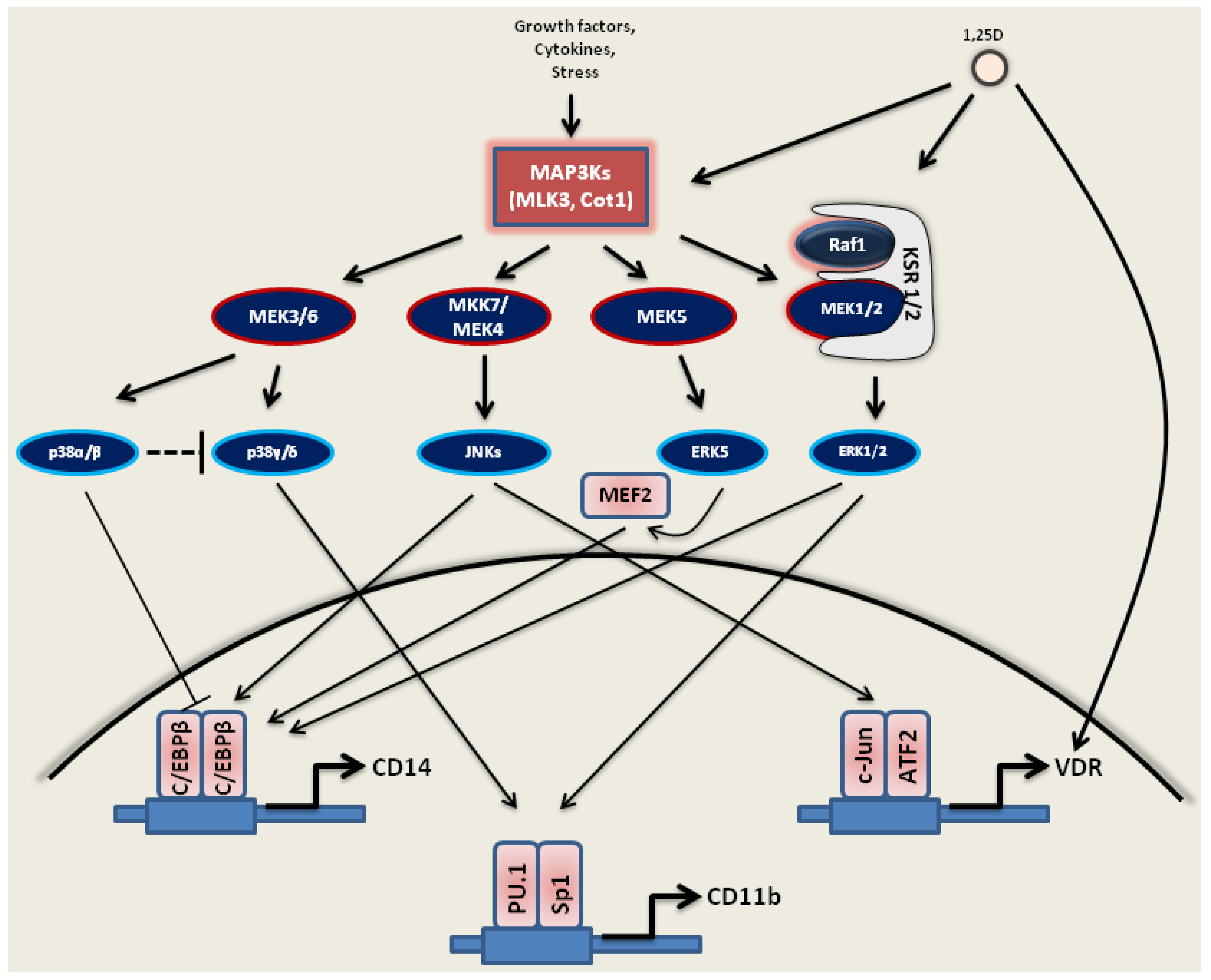

2.1. MAP Kinase Signaling

2.1.1. MEK1/2-ERK1/2 Pathway

2.1.2. JNKs Pathway

2.1.3. p38 Kinases Pathway

2.1.4. MEK5-ERK5-MEF2C Pathway

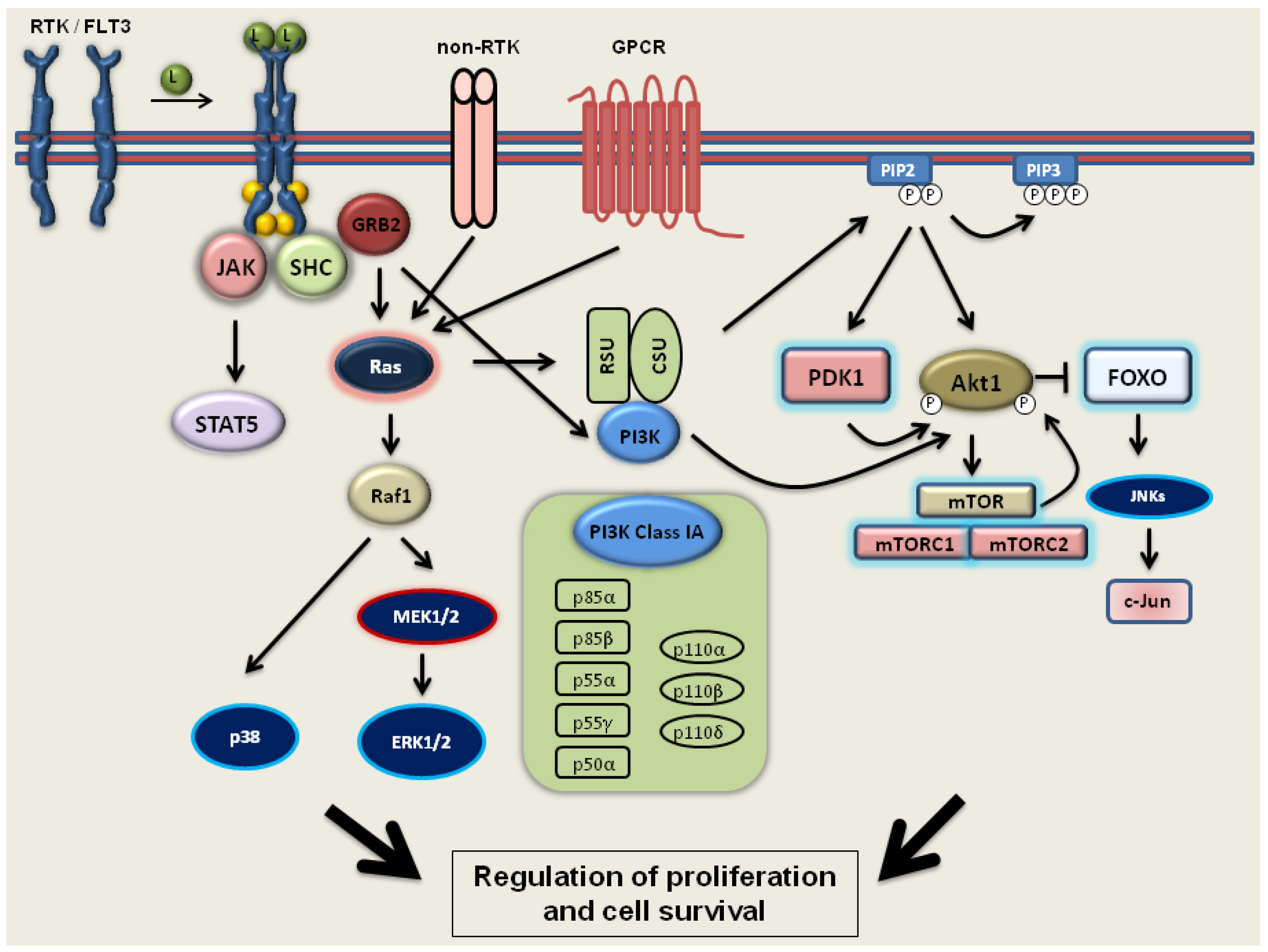

2.2. PI3 Kinase-Akt1-mTOR Signaling

2.3. FLT3 Signaling

2.4. C/EBPα Signaling

2.5. Targeting by MicroRNAs

2.6. Global Effects of VDDs on AML Cells

3. 1,25D as an Important Modifier of Signaling Pathways Disturbed in AML

3.1. Activation of MAPKs by 1,25D

3.1.1. Ras1-Raf1-MEK1/2-ERK1/2

3.1.2. JNKs

3.1.3. MAPK/p38 Kinases

3.1.4. MEK5-ERK5-MEF2C

3.2. The Effect of 1,25D on the PI3 Kinase-Akt1-mTOR Pathway

3.3. The Influence of 1,25D on AML Cells with Mutated FLT3 Kinase

3.4. Effects of 1,25D on C/EBPα

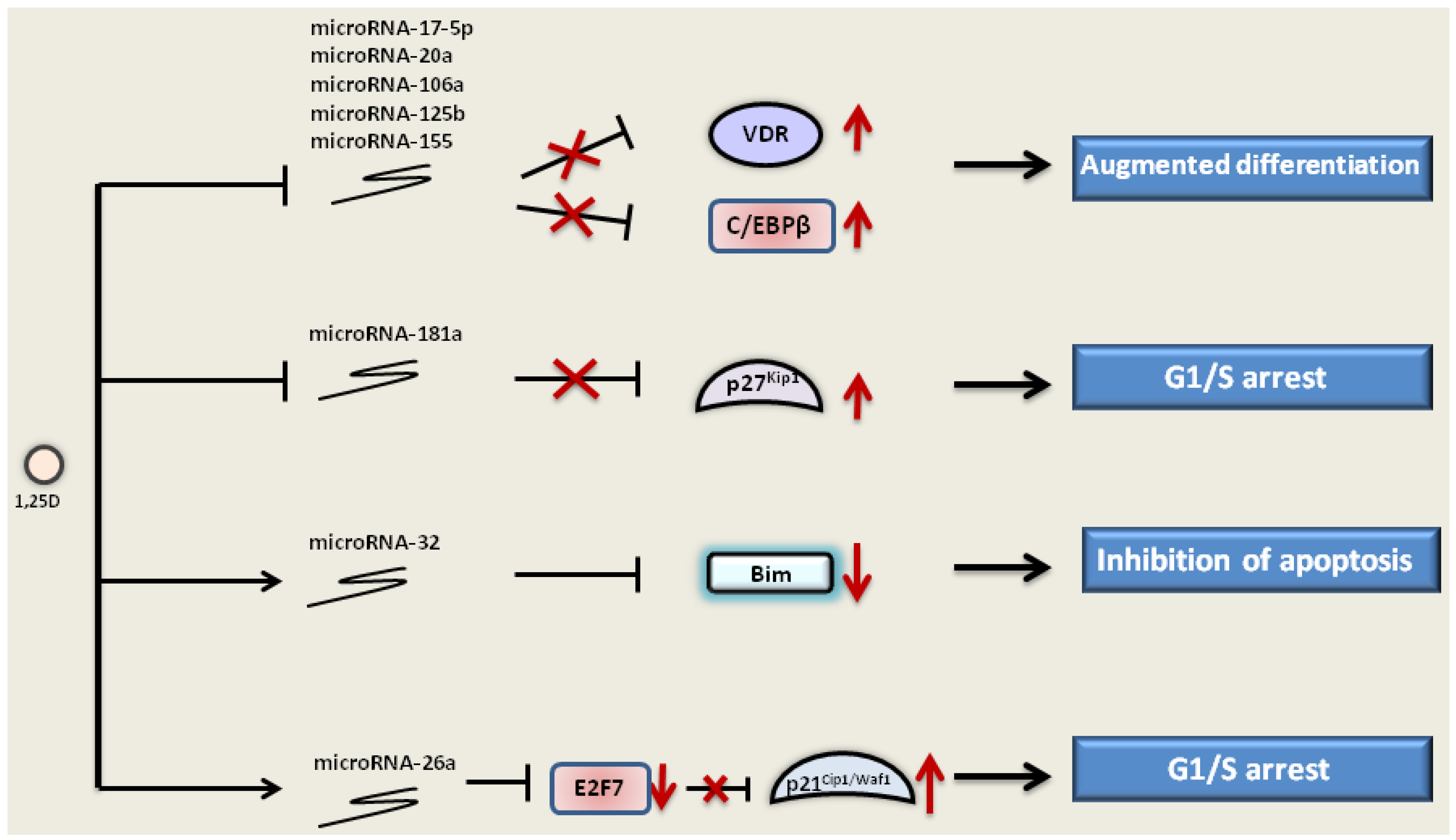

3.5. The Effect of 1,25D on MicroRNAs

) and elevated expression of p27Kip1 (). 1,25D also downregulates other microRNAs, such as microRNA-106a, -20a and -155, that target and inhibit the expression of VDR and C/EBPβ. 1,25D can up-regulate () microRNA-32, which targets pro-apoptotic protein Bim and inhibits its expression (). Furthermore, microRNA-26a is upregulated by 1,25D. MicroRNA-26a inhibits transcriptional repressor E2F7, which, in turn, no longer inhibits p21Cip1/Waf1, and its expression is elevated. Regulation of microRNA expression by 1,25D leads to the augmented differentiation, inhibition of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in the G1/S phase.

) and elevated expression of p27Kip1 (). 1,25D also downregulates other microRNAs, such as microRNA-106a, -20a and -155, that target and inhibit the expression of VDR and C/EBPβ. 1,25D can up-regulate () microRNA-32, which targets pro-apoptotic protein Bim and inhibits its expression (). Furthermore, microRNA-26a is upregulated by 1,25D. MicroRNA-26a inhibits transcriptional repressor E2F7, which, in turn, no longer inhibits p21Cip1/Waf1, and its expression is elevated. Regulation of microRNA expression by 1,25D leads to the augmented differentiation, inhibition of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in the G1/S phase.

4. Potentiators of 1,25D-Induced Differentiation of AML Cells

| Compound | Characteristic | Mode of Action with 1,25D | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutlin 3a | cis-imidazoline analog, inhibits interaction between Mdm2 and p53 | ▪ downregulation of Bcl-2, MDMX, KSR2, phospho-ERK2 ▪ upregulation of PIG-6 | [152] |

| Carnosic acid | natural benzenediol abietane diterpene from rosemary | ▪ upregulation of ERK5, c-Jun and AP1 ▪ downregulation of microRNA-181a expression | [189,196,197] |

| Curcumin | diarylheptanoid, natural phenol from turmeric | ▪ activation of caspase-3, -8 and -9 | [195] |

| Silibinin | flavonolignan from the milk thistle seeds | ▪ upregulation of c-Jun and C/EBPβ | [199,200] |

| Everolimus | 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl) derivative of sirolimus | ▪ inhibition of Akt/mTOR | [201] |

| Deferasirox | iron chelator | ▪ induction of VDR expression and phosphorylation | [204,207] |

| Q-VD-OPh | pan-caspase inhibitor | ▪ upregulation of HPK1 and c-Jun | [205] |

| Indomethacin | non-steroid inhibitor of cyclooxygenase | ▪ inhibition of phospho-Raf1 | [206] |

5. Clinical Trials with VDDs Targeting Signaling Pathways in AML

| Target | Compounds | Phase | Status of the study | Examples of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle inhibition | rigosertib | I/II | ongoing, recruitment closed | NCT01167166 |

| volasertib | I | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT02003573 | |

| Cytotoxicty | clofarabine | I | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01289457 |

| sapacitabine | III | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01303796 | |

| vosaroxin | I/II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01893320 | |

| DNA hypomethylation | azacitidine | II | ongoing, no recruitment | NCT01358734 |

| decitabine | II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT02188706 | |

| SGI-110 | II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT02096055 | |

| FLT3 small-molecule inhibitors | crenolanib | II | ongoing, recur | NCT01657682 |

| midostaurin | I/II | itment opened | NCT01093573 | |

| sorafenib | II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT02196857 | |

| not yet open for recruitment | ||||

| Histone deacetylase inhibitors | panobinostat | I/II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01451268 |

| pracinostat | II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01912274 | |

| vorinostat | I | ongoing, no recruiment | NCT00875745 | |

| Monoclonal antibodies | gemtuzumab ozogamicin | III | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT00893399 |

| SGN33a | I | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01902329 | |

| MEK inhibitors | MEK162 | I/II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT02089230 |

| trametinib (GSK1120212) | II | ongoing, recruitment opened | NCT01907815 |

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Abbreviations

| 1,25D | 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 |

| Akt1 | protein kinase B |

| ALL | acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| AP1 | activator protein 1 |

| APL | acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| ATF2 | activating transcription factor 2 |

| ATRA | all-trans retinoic acid |

| CA | carnosic acid |

| C/EBPs | CCAAT enhancer binding proteins |

| CML | chronic myelogenous leukemia |

| Cot1 | cancer Osaka thyroid 1 |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase |

| FLT3 | FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 |

| GPCRs | G-protein-coupled receptors |

| GWA | genome-wide association |

| JNKs | c-Jun N-terminal kinases |

| KSR | kinase suppressor of Ras |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated kinase |

| MAP2K | mitogen-activated kinase kinase |

| MAP3K | mitogen-activated kinase kinase kinase |

| MDS | myelodysplastic syndrome |

| MEF2 | myogenic enhancer factor 2 |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| non-RTKs | non-receptor tyrosine kinases |

| PDK1 | 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-linase |

| PIP2 | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate |

| PIP3 | phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate |

| RTKs | receptor tyrosine kinases |

| TF | transcription factor |

| TKD | Tyrosine Kinase Domain |

| VDDs | vitamin D compounds/derivatives |

| VDR | vitamin D receptor |

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowell, P.C. Differentiation of human leukemic leukocytes in tissue culture. Exp. Cell Res. 1960, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugo, T.G.; Pendergast, A.M.; Muller, A.J.; Witte, O.N. Tyrosine kinase activity and transformation potency of Bcr-Abl oncogene products. Science 1990, 247, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druker, B.J.; Tamura, S.; Buchdunger, E.; Ohno, S.; Segal, G.M.; Fanning, S.; Zimmermann, J.; Lydon, N.B. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druker, B.J.; Sawyers, C.L.; Kantarjian, H.; Resta, D.J.; Reese, S.F.; Ford, J.M.; Capdeville, R.; Talpaz, M. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, J.D.; Golomb, H.M.; Dougherty, C. 15/17 translocation, a consistent chromosomal change in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Lancet 1977, 1, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrow, J.; Goddard, A.D.; Sheer, D.; Solomon, E. Molecular analysis of acute promyelocytic leukemia breakpoint cluster region on chromosome 17. Science 1990, 249, 1577–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, L.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Biondi, A.; Rambaldi, A.; Mencarelli, A.; Lo Coco, F.; Diverio, D.; Pegoraro, L.; Avanzi, G.; Tabilio, A.; et al. Rearrangements and aberrant expression of the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene in acute promyelocytic leukemias. J. Exp. Med. 1990, 172, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grignani, F.; De Matteis, S.; Nervi, C.; Tomassoni, L.; Gelmetti, V.; Cioce, M.; Fanelli, M.; Ruthardt, M.; Ferrara, F.F.; Zamir, I.; et al. Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-alpha recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature 1998, 391, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidez, F.; Ivins, S.; Zhu, J.; Soderstrom, M.; Waxman, S.; Zelent, A. Reduced retinoic acid-sensitivities of nuclear receptor corepressor binding to PML- and PLZF-RARalpha underlie molecular pathogenesis and treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1998, 91, 2634–2642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petrie, K.; Zelent, A.; Waxman, S. Differentiation therapy of acute myeloid leukemia: Past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2009, 16, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, Q.T.; Koeffler, H.P. Vitamin D compounds in leukemia. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 97, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Mizusawa, M.; Harima, A.; Kajiwara, K.; Hamaki, T.; Hoshi, K.; Kozai, Y.; Kodo, H. Induction of remission of relapsed acute myeloid leukemia after unrelated donor cord blood transplantation by concomitant low-dose cytarabine and calcitriol in adults. Eur. J. Haematol. 2006, 77, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, F.; Fazi, P.; Venditti, A.; Pagano, L.; Amadori, S.; Mandelli, F. Heterogeneity in the therapeutic approach to relapsed elderly patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: A survey from the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’ Adulto (GIMEMA) Acute Leukaemia Working Party. Hematol. Oncol. 2008, 26, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendik, I.; Friedel, A.; Roos, F.F.; Weber, P.; Eggersdorfer, M. Vitamin D: A critical and essential micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol 2014, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Mirandola, L.; Pandey, A.; Nguyen, D.D.; Jenkins, M.R.; Turcel, M.; Cobos, E.; Chiriva-Internati, M. Application of vitamin D and derivatives in hematological malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2012, 319, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.S.; Bershadskiy, A. Clinical experience using vitamin D analogs in the treatment of myelodysplasia and acute myleoid leukemia: A review of the literature. Leuk. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.C.; Juckett, M.B. The role of vitamin D in hematologic disease and stem cell transplantation. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2206–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchwicka, A.; Cebrat, M.; Sampath, P.; Sniezewski, L.; Marcinkowska, E. Perspectives of differentiation therapies of acute myeloid leukemia: The search for the molecular basis of patients’ variable responses to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and vitamin D analogs. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowenberg, B. Acute myeloid leukemia: The challenge of capturing disease variety. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Progr. 2008, 2008, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardiman, J.W. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: An overview with emphasis on the myeloid neoplasms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 184, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasserjian, R.P. Acute myeloid leukemia: Advances in diagnosis and classification. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2013, 35, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.M.; Catovsky, D.; Daniel, M.T.; Flandrin, G.; Galton, D.A.; Gralnick, H.R.; Sultan, C. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br. J. Haematol. 1976, 33, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardiman, J.W.; Harris, N.L.; Brunning, R.D. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2002, 100, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bories, P.; Bertoli, S.; Berard, E.; Laurent, J.; Duchayne, E.; Sarry, A.; Delabesse, E.; Beyne-Rauzy, O.; Huguet, F.; Recher, C. Intensive chemotherapy, azacitidine or supportive care in older acute myeloid leukemia patients: An analysis from a regional healthcare network. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.A.; Valk, P.J. The evolving molecular genetic landscape in acute myeloid leukaemia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2013, 20, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Wahab, O.; Levine, R.L. Mutations in epigenetic modifiers in the pathogenesis and therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013, 121, 3563–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estey, E.H. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2013 update on risk-stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2013, 88, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.C.; Levine, R.L. Translational implications of somatic genomics in acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e382–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.E.; Ye, Y.C.; Chen, S.R.; Chai, J.R.; Lu, J.X.; Zhoa, L.; Gu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Y. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1988, 72, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ades, L.; Chevret, S.; Raffoux, E.; Guerci-Bresler, A.; Pigneux, A.; Vey, N.; Lamy, T.; Huguet, F.; Vekhoff, A.; Lambert, J.F.; et al. Long-term follow-up of European APL 2000 trial, evaluating the role of cytarabine combined with ATRA and Daunorubicin in the treatment of nonelderly APL patients. Am. J. Hematol. 2013, 88, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cull, E.H.; Altman, J.K. Contemporary treatment of APL. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2014, 9, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honma, Y.; Hozumi, M.; Abe, E.; Konno, K.; Fukushima, M.; Hata, S.; Nishii, Y.; DeLuca, H.F.; Suda, T. 1 alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 1 alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 prolong survival time of mice inoculated with myeloid leukemia cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, D.M.; San Miguel, J.F.; Freake, H.C.; Green, P.M.; Zola, H.; Catovsky, D.; Goldman, J.M. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits proliferation of human promyelocytic leukaemia (HL60) cells and induces monocyte-macrophage differentiation in HL60 and normal human bone marrow cells. Leuk. Res. 1983, 7, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzinski, G.P.; Bhandal, A.K.; Brelvi, Z.S. A system for monocytic differentiation of leukemic cells HL 60 by a short exposure to 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1985, 179, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzinski, G.P.; Bhandal, A.K.; Brelvi, Z.S. Cell cycle sensitivity of HL-60 cells to the differentiation-inducing effects of 1-alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 1985, 45, 3898–3905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brelvi, Z.S.; Studzinski, G.P. Changes in the expression of oncogenes encoding nuclear phosphoproteins but not c-Ha-ras have a relationship to monocytic differentiation of HL 60 cells. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 2234–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, M.; Chen, W.; Cobb, M.H. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3100–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geest, C.R.; Coffer, P.J. MAPK signaling pathways in the regulation of hematopoiesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Bao, Z.Q.; Dixon, J.E. Components of a new human protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 12665–12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Rao, J.; Studzinski, G.P. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity up-regulates multiple MAP kinase pathways and potentiates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of human leukemia HL60 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 258, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Inhibition of p38MAP kinase potentiates the JNK/SAPK pathway and AP-1 activity in monocytic but not in macrophage or granulocytic differentiation of HL60 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 82, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Oncoprotein Cot1 represses kinase suppressors of Ras1/2 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Lu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chang, G.; Lin, Y.; Pang, T. Down-regulation of the P-glycoprotein relevant for multidrug resistance by intracellular acidification through the crosstalk of MAPK signaling pathways. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 54, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.; Steelman, L.S.; Lee, J.T.; Shelton, J.G.; Navolanic, P.M.; Blalock, W.L.; Franklin, R.A.; McCubrey, J.A. Signal transduction mediated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway from cytokine receptors to transcription factors: Potential targeting for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia 2003, 17, 1263–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, E.; Garay, E.; Gocek, E.; Chrobak, A.; Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Regulation of C/EBPbeta isoforms by MAPK pathways in HL60 cells induced to differentiate by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 2054–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.B.; Xu, H.; Torchia, J.A.; Johnson, D.E. Cytokine-induced myeloid differentiation is dependent on activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. Leuk. Res. 2005, 29, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.E.; Radomska, H.S.; Wu, B.; Zhang, P.; Winnay, J.N.; Bajnok, L.; Wright, W.S.; Schaufele, F.; Tenen, D.G.; MacDougald, O.A. Phosphorylation of C/EBPalpha inhibits granulopoiesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, D.K. KSR: A MAPK scaffold of the Ras pathway? J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 1609–1612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Kinase suppressor of RAS (KSR) amplifies the differentiation signal provided by low concentrations 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Cell. Physiol. 2004, 198, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, M.M.; Ritt, D.A.; Morrison, D.K. Signaling dynamics of the KSR1 scaffold complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11022–11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Koo, C.Y.; Stebbing, J.; Giamas, G. The dual function of KSR1: A pseudokinase and beyond. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Bjorbaek, C.; Moller, D.E. Regulation and interaction of p90 (Rsk) isoforms with mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 29773–29779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) defines the first phase of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL60 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 80, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Raf-1 signaling is required for the later stages of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL60 cells but is not mediated by the MEK/ERK module. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 209, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibi, M.; Lin, A.; Smeal, T.; Minden, A.; Karin, M. Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 2135–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluss, H.K.; Barrett, T.; Derijard, B.; Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor mediated by JNK protein kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 8376–8384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Gallagher, E. From JNK to pay dirt: Jun kinases, their biochemistry, physiology and clinical importance. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, C.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Cavanagh, J.; Barrett, T.; Davis, R.J. The MKK7 gene encodes a group of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Banerjee, P.; Nikolakaki, E.; Dai, T.; Rubie, E.A.; Ahmad, M.F.; Avruch, J.; Woodgett, J.R. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature 1994, 369, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Giraud, J.; Davis, R.J.; White, M.F. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediates feedback inhibition of the insulin signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2896–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. The requirement for and changing composition of the activating protein-1 transcription factor during differentiation of human leukemia HL60 cells induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4402–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, M.; Narang, H. The complexity of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) made simple. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3525–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, K.K.; Trollinger, D.; Rihanek, M.; Manthey, C.L. Differential expression and activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase alpha, beta, gamma, and delta in inflammatory cell lineages. J. Immunol. 1999, 162, 4246–4252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uddin, S.; Ah-Kang, J.; Ulaszek, J.; Mahmud, D.; Wickrema, A. Differentiation stage-specific activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms in primary human erythroid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Posner, G.H.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. Differentiation-inducing potency of the seco-steroid JK-1624F2–2 can be increased by combination with an antioxidant and a p38MAPK inhibitor which upregulates the JNK pathway. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 105, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Harrison, J.S.; Studzinski, G.P. Isoforms of p38MAPK gamma and delta contribute to differentiation of human AML cells induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Gram, H.; Zhao, M.; New, L.; Gu, J.; Feng, L.; Di Padova, F.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Han, J. Characterization of the structure and function of the fourth member of p38 group mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38delta. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30122–30128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Brey, P.T.; Lee, W.J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Drosophila p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarubin, T.; Han, J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancho, D.; Tanaka, N.; Jaeschke, A.; Ventura, J.J.; Kelkar, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Kyuuma, M.; Takeshita, T.; Flavell, R.A.; Davis, R.J. Mechanism of p38 MAP kinase activation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, K.; Mistry, P.; Chernoff, J.; Blank, J.L.; Patel, R. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates cell death and p21-activated kinase mediates cell survival during chemotherapeutic drug-induced mitotic arrest. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 2071–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Nebreda, A.R. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem. J. 2010, 429, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, A.L.; Hayward, N.K. Molecular pathways: Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mutations and drug resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tournier, C. Regulation of cellular functions by the ERK5 signalling pathway. Cell Signal. 2006, 18, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pesakhov, S.; Harrison, J.S.; Kafka, M.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. The MAPK ERK5, but not ERK1/2, inhibits the progression of monocytic phenotype to the functioning macrophage. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 330, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Johnson, G.L. PB1 domains of MEKK2 and MEKK3 interact with the MEK5 PB1 domain for activation of the ERK5 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36989–36992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, J.; Wang, X.; Kharebava, G.; Tournier, C. A novel mitogen-activated protein kinase docking site in the N terminus of MEK5alpha organizes the components of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9820–9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Royuela, N.; Rathore, M.G.; Allende-Vega, N.; Annicotte, J.S.; Fajas, L.; Ramachandran, B.; Gulick, T.; Villalba, M. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 5 modulates the antioxidant response by transcriptionally controlling Sirtuin 1 expression in leukemic cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 53, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondoh, K.; Terasawa, K.; Morimoto, H.; Nishida, E. Regulation of nuclear translocation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 by active nuclear import and export mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, N.; Campbell, D.G.; Morrice, N.; Peggie, M.; Cohen, P. An analysis of the phosphorylation and activation of extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinase 5 (ERK5) by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 5 (MKK5) in vitro. Biochem. J. 2003, 372, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Kondoh, K.; Nishimoto, S.; Terasawa, K.; Nishida, E. Activation of a C-terminal transcriptional activation domain of ERK5 by autophosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 35449–35456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kravchenko, V.V.; Tapping, R.I.; Han, J.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Lee, J.D. BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 7054–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamakura, S.; Moriguchi, T.; Nishida, E. Activation of the protein kinase ERK5/BMK1 by receptor tyrosine kinases. Identification and characterization of a signaling pathway to the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26563–26571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, K.; Okazaki, K.; Nishida, E. Regulation of c-Fos and Fra-1 by the MEK5-ERK5 pathway. Genes Cells 2003, 8, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buschbeck, M.; Ullrich, A. The unique C-terminal tail of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 regulates its activation and nuclear shuttling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2659–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiariello, M.; Marinissen, M.J.; Gutkind, J.S. Multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways connect the Cot oncoprotein to the c-Jun promoter and to cellular transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 1747–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gocek, E.; Novik, V.; Harrison, J.S.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. Inhibition of Cot1/Tlp2 oncogene in AML cells reduces ERK5 activation and up-regulates p27Kip1 concomitant with enhancement of differentiation and cell cycle arrest induced by silibinin and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 4542–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katso, R.; Okkenhaug, K.; Ahmadi, K.; White, S.; Timms, J.; Waterfield, M.D. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: Implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 17, 615–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciruelos Gil, E.M. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 40, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Ottmann, O.G.; Deininger, M.; Hochhaus, A. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 2014, 99, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; McIlroy, J.; Rordorf-Nikolic, T.; Orr, G.A.; Backer, J.M. Regulation of the p85/p110 phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase: Stabilization and inhibition of the p110alpha catalytic subunit by the p85 regulatory subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, P.T.; Anderson, K.E.; Davidson, K.; Stephens, L.R. Signalling through Class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krugmann, S.; Hawkins, P.T.; Pryer, N.; Braselmann, S. Characterizing the interactions between the two subunits of the p101/p110gamma phosphoinositide 3-kinase and their role in the activation of this enzyme by G beta gamma subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 17152–17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Lee, S.H.; Zhang, J.; Signoretti, S.; Loda, M.; Roberts, T.M.; et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature 2008, 454, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saudemont, A.; Garcon, F.; Yadi, H.; Roche-Molina, M.; Kim, N.; Segonds-Pichon, A.; Martin-Fontecha, A.; Okkenhaug, K.; Colucci, F. p110gamma and p110delta isoforms of phosphoinositide 3-kinase differentially regulate natural killer cell migration in health and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5795–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murga, C.; Laguinge, L.; Wetzker, R.; Cuadrado, A.; Gutkind, J.S. Activation of Akt/protein kinase B by G protein-coupled receptors. A role for alpha and beta gamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins acting through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinasegamma. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 19080–19085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurig, B.; Shymanets, A.; Bohnacker, T.; Prajwal; Brock, C.; Ahmadian, M.R.; Schaefer, M.; Gohla, A.; Harteneck, C.; Wymann, M.P.; et al. Ras is an indispensable coregulator of the class IB phosphoinositide 3-kinase p87/p110gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20312–20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Sengupta, S.; Sheen, J.H.; Hsu, P.P.; Bagley, A.F.; Markhard, A.L.; Sabatini, D.M. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol. Cell 2006, 22, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayascas, J.R. Dissecting the role of the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) signalling pathways. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2978–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, A.; Sanda, T.; Grebliunaite, R.; Carracedo, A.; Salmena, L.; Ahn, Y.; Dahlberg, S.; Neuberg, D.; Moreau, L.A.; Winter, S.S.; et al. High frequency of PTEN, PI3K, and AKT abnormalities in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2009, 114, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, S.M.; Lane, S.W.; Bullinger, L.; Kalaitzidis, D.; Yusuf, R.; Saez, B.; Ferraro, F.; Mercier, F.; Singh, H.; Brumme, K.M.; et al. AKT/FOXO signaling enforces reversible differentiation blockade in myeloid leukemias. Cell 2011, 146, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, J.; Chapuis, N.; Bardet, V.; Park, S.; Sujobert, P.; Willems, L.; Ifrah, N.; Dreyfus, F.; Mayeux, P.; Lacombe, C.; et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt by up-regulating insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling in acute myeloid leukemia: Rationale for therapeutic inhibition of both pathways. Blood 2008, 111, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, C.; Fruman, D.A. Target of rapamycin signaling in leukemia and lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5374–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, J.K.; Sassano, A.; Platanias, L.C. Targeting mTOR for the treatment of AML. New agents and new directions. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosnet, O.; Birnbaum, D. Hematopoietic receptors of class III receptor-type tyrosine kinases. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1993, 4, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lyman, S.D. Biology of flt3 ligand and receptor. Int. J. Hematol. 1995, 62, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnittger, S.; Schoch, C.; Dugas, M.; Kern, W.; Staib, P.; Wuchter, C.; Loffler, H.; Sauerland, C.M.; Serve, H.; Buchner, T.; et al. Analysis of FLT3 length mutations in 1003 patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Correlation to cytogenetics, FAB subtype, and prognosis in the AMLCG study and usefulness as a marker for the detection of minimal residual disease. Blood 2002, 100, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiede, C.; Steudel, C.; Mohr, B.; Schaich, M.; Schakel, U.; Platzbecker, U.; Wermke, M.; Bornhauser, M.; Ritter, M.; Neubauer, A.; et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: Association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood 2002, 99, 4326–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janke, H.; Pastore, F.; Schumacher, D.; Herold, T.; Hopfner, K.P.; Schneider, S.; Berdel, W.E.; Buchner, T.; Woermann, B.J.; Subklewe, M.; et al. Activating FLT3 mutants show distinct gain-of-function phenotypes in vitro and a characteristic signaling pathway profile associated with prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, S.; Kiyoi, H.; Nakao, M.; Iwai, T.; Misawa, S.; Okuda, T.; Sonoda, Y.; Abe, T.; Kahsima, K.; Matsuo, Y.; et al. Internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene is preferentially seen in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome among various hematological malignancies. A study on a large series of patients and cell lines. Leukemia 1997, 11, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, C.; Muller-Tidow, C.; Berdel, W.E.; Serve, H. Signal transduction of oncogenic Flt3. Int. J. Hematol. 2005, 82, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S. Downstream molecular pathways of FLT3 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia: Biology and therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenen, D.G.; Hromas, R.; Licht, J.D.; Zhang, D.E. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood 1997, 90, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pabst, T.; Mueller, B.U.; Zhang, P.; Radomska, H.S.; Narravula, S.; Schnittger, S.; Behre, G.; Hiddemann, W.; Tenen, D.G. Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha), in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porse, B.T.; Bryder, D.; Theilgaard-Monch, K.; Hasemann, M.S.; Anderson, K.; Damgaard, I.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Nerlov, C. Loss of C/EBP alpha cell cycle control increases myeloid progenitor proliferation and transforms the neutrophil granulocyte lineage. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.T.; MacDougald, O.A.; Diehl, A.M.; Lane, M.D. A 30-kDa alternative translation product of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha message: Transcriptional activator lacking antimitotic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9606–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirstetter, P.; Schuster, M.B.; Bereshchenko, O.; Moore, S.; Dvinge, H.; Kurz, E.; Theilgaard-Monch, K.; Mansson, R.; Pedersen, T.A.; Pabst, T.; et al. Modeling of C/EBPalpha mutant acute myeloid leukemia reveals a common expression signature of committed myeloid leukemia-initiating cells. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkhoven, C.F.; Muller, C.; Leutz, A. Translational control of C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta isoform expression. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1920–1932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Iwasaki-Arai, J.; Iwasaki, H.; Fenyus, M.L.; Dayaram, T.; Owens, B.M.; Shigematsu, H.; Levantini, E.; Huettner, C.S.; Lekstrom-Himes, J.A.; et al. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell repopulating capacity and self-renewal in the absence of the transcription factor C/EBP alpha. Immunity 2004, 21, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenk, R.F.; Dohner, K.; Krauter, J.; Frohling, S.; Corbacioglu, A.; Bullinger, L.; Habdank, M.; Spath, D.; Morgan, M.; Benner, A.; et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl, T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 2001, 294, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, M.; Garzon, R.; Andreeff, M.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Calin, G.A. MicroRNAs and noncoding RNAs in hematological malignancies: Molecular, clinical and therapeutic implications. Leukemia 2008, 22, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcucci, G.; Radmacher, M.D.; Maharry, K.; Mrozek, K.; Ruppert, A.S.; Paschka, P.; Vukosavljevic, T.; Whitman, S.P.; Baldus, C.D.; Langer, C.; et al. MicroRNA expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzeler, K.H.; Maharry, K.; Kohlschmidt, J.; Volinia, S.; Mrozek, K.; Becker, H.; Nicolet, D.; Whitman, S.P.; Mendler, J.H.; Schwind, S.; et al. A stem cell-like gene expression signature associates with inferior outcomes and a distinct microRNA expression profile in adults with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2023–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcucci, G.; Maharry, K.S.; Metzeler, K.H.; Volinia, S.; Wu, Y.Z.; Mrozek, K.; Nicolet, D.; Kohlschmidt, J.; Whitman, S.P.; Mendler, J.H.; et al. Clinical role of microRNAs in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: MiR-155 upregulation independently identifies high-risk patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2086–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimenes-Teixeira, H.L.; Lucena-Araujo, A.R.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Zanette, D.L.; Scheucher, P.S.; Oliveira, L.C.; Dalmazzo, L.F.; Silva-Junior, W.A.; Falcao, R.P.; Rego, E.M. Increased expression of miR-221 is associated with shorter overall survival in T-cell acute lymphoid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.D.; Sucheston-Campbell, L.E.; Campbell, M.J. Vitamin D Receptor and RXR in the Post-Genomic Era. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 230, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.J. Vitamin D and the RNA transcriptome: More than mRNA regulation. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkinen, S.; Vaisanen, S.; Pehkonen, P.; Seuter, S.; Benes, V.; Carlberg, C. Nuclear hormone 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 elicits a genome-wide shift in the locations of VDR chromatin occupancy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9181–9193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryynanen, J.; Seuter, S.; Campbell, M.J.; Carlberg, C. Gene regulatory scenarios of primary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target genes in a human myeloid leukemia cell line. Cancers (Basel) 2013, 5, 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramagopalan, S.V.; Heger, A.; Berlanga, A.J.; Maugeri, N.J.; Lincoln, M.R.; Burrell, A.; Handunnetthi, L.; Handel, A.E.; Disanto, G.; Orton, S.M.; et al. A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: Associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, G.P. IUPAC-IUB Nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989. Pure Appl. Chem. 1989, 61, 1783–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Wang, J.; Janjetovic, Z.; Chen, J.; Tuckey, R.C.; Nguyen, M.N.; Tang, E.K.; Miller, D.; Li, W.; Slominski, A.T. Correlation between secosteroid-induced vitamin D receptor activity in melanoma cells and computer-modeled receptor binding strength. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 361, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, H.A. Vitamin D activities for health outcomes. Ann. Lab. Med. 2014, 34, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocek, E.; Studzinski, G.P. Vitamin D and differentiation in cancer. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009, 46, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grober, U.; Spitz, J.; Reichrath, J.; Kisters, K.; Holick, M.F. Vitamin D: Update 2013: From rickets prophylaxis to general preventive healthcare. Dermatoendocrinology 2013, 5, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.; Krishnan, A.V.; Swami, S.; Giovannucci, E.; Feldman, B.J. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutsch, R.; Kandemir, J.D.; Pietsch, D.; Cappello, C.; Meyer, J.; Simanowski, K.; Huber, R.; Brand, K. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta inhibits proliferation in monocytic cells by affecting the retinoblastoma protein/E2F/cyclin E pathway but is not directly required for macrophage morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 22716–22729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pesakhov, S.; Harrison, J.S.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. ERK5 pathway regulates transcription factors important for monocytic differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 229, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickstein, D.D.; Ozols, J.; Williams, S.A.; Baenziger, J.U.; Locksley, R.M.; Roth, G.J. Isolation and characterization of the receptor on human neutrophils that mediates cellular adherence. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 5576–5580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.D.; Ramos, R.A.; Tobias, P.S.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Mathison, J.C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 1990, 249, 1431–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzinski, G.P.; Rathod, B.; Wang, Q.M.; Rao, J.; Zhang, F. Uncoupling of cell cycle arrest from the expression of monocytic differentiation markers in HL60 cell variants. Exp. Cell Res. 1997, 232, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocek, E.; Kielbinski, M.; Baurska, H.; Haus, O.; Kutner, A.; Marcinkowska, E. Different susceptibilities to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of AML cells carrying various mutations. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, E. Evidence that activation of MEK1,2/Erk1,2 signal transduction pathway is necessary for calcitriol-induced differentiation of HL60 cells. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Jun N-terminal kinase pathway enhances signaling of monocytic differentiation of human leukemia cells induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 89, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.M.; Jones, J.B.; Studzinski, G.P. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 as a mediator of the G1/S phase block induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in HL60 cells. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.M.; Studzinski, G.P.; Chen, F.; Coffman, F.D.; Harrison, L.E. p53/56(lyn) antisense shifts the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced G1/S block in HL60 cells to S phase. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000, 183, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Studzinski, G.P. AKT pathway is activated by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and participates in its anti-apoptotic effect and cell cycle control in differentiating HL60 cells. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.M.; Tepper, C.G.; Jones, J.B.; Fernandez, C.E.; Studzinski, G.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 protects HL60 cells against apoptosis but down-regulates the expression of the Bcl-2 gene. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 209, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Andreeff, M.; Studzinski, G.P.; Vassilev, L.T. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances the apoptotic activity of MDM2 antagonist nutlin-3a in acute myeloid leukemia cells expressing wild-type p53. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.T.; Pang, L.; Decker, S.J.; Bridges, A.J.; Saltiel, A.R. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 7686–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramji, D.P.; Foka, P. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: Structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 2002, 365, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huber, R.; Pietsch, D.; Panterodt, T.; Brand, K. Regulation of C/EBPbeta and resulting functions in cells of the monocytic lineage. Cell Signal. 2012, 24, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzinski, G.P.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Kutner, A.; Harrison, J.S. The rationale for deltanoids in therapy for myeloid leukemia: Role of KSR-MAPK-C/EBP pathway. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 97, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, M.; Poli, V.; Hunter, T.; Chojkier, M. C/EBPbeta phosphorylation by RSK creates a functional XEXD caspase inhibitory box critical for cell survival. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Hetherington, C.J.; Zhang, D.E. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein activates the CD14 promoter and mediates transforming growth factor beta signaling in monocyte development. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23242–23248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, N.R.; Therrien, M.; Cacace, A.; Edsall, L.C.; Spiegel, S.; Rubin, G.M.; Morrison, D.K. KSR stimulates Raf-1 activity in a kinase-independent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12792–12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.T.; White, J.H.; Studzinski, G.P. Induction of kinase suppressor of RAS-1(KSR-1) gene by 1, alpha25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human leukemia HL60 cells through a vitamin D response element in the 5'-flanking region. Oncogene 2006, 25, 7078–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.T.; White, J.H.; Studzinski, G.P. Expression of human kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (hKSR-2) gene in HL60 leukemia cells is directly upregulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and is required for optimal cell differentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 2007, 313, 3034–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Patel, R.; Studzinski, G.P. hKSR-2, a vitamin D-regulated gene, inhibits apoptosis in arabinocytosine-treated HL60 leukemia cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2798–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Mishra, N.C.; Yoshida, K.; Kharbanda, S.; Saxena, S.; Kufe, D. Mitochondrial targeting of JNK/SAPK in the phorbol ester response of myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, E.; Preis, L.H.; Birrer, M.J. Constitutive cJun expression induces partial macrophage differentiation in U-937 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994, 5, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.L.; Sasaki, D.T.; Murray, B.W.; O'Leary, E.C.; Sakata, S.T.; Xu, W.; Leisten, J.C.; Motiwala, A.; Pierce, S.; Satoh, Y.; et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 13681–13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Salman, H.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. Cooperation between antioxidants and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in induction of leukemia HL60 cell differentiation through the JNK/AP-1/Egr-1 pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005, 204, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeschke, A.; Karasarides, M.; Ventura, J.J.; Ehrhardt, A.; Zhang, C.; Flavell, R.A.; Shokat, K.M.; Davis, R.J. JNK2 is a positive regulator of the cJun transcription factor. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabapathy, K.; Wagner, E.F. JNK2: A negative regulator of cellular proliferation. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 1520–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen-Deutsch, X.; Garay, E.; Zhang, J.; Harrison, J.S.; Studzinski, G.P. c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 (JNK2) antagonizes the signaling of differentiation by JNK1 in human myeloid leukemia cells resistant to vitamin D. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenda, A.; Rouse, J.; Doza, Y.N.; Meier, R.; Cohen, P.; Gallagher, T.F.; Young, P.R.; Lee, J.C. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995, 364, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto, S.; Xiang, J.; Huang, S.; Lin, A. Induction of apoptosis by SB202190 through inhibition of p38beta mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 16415–16420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthey, C.L.; Wang, S.W.; Kinney, S.D.; Yao, Z. SB202190, a selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, is a powerful regulator of LPS-induced mRNAs in monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998, 64, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gocek, E.; Kielbinski, M.; Marcinkowska, E. Activation of intracellular signaling pathways is necessary for an increase in VDR expression and its nuclear translocation. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatake, R.J.; O’Neill, M.M.; Kennedy, C.A.; Wayne, A.L.; Jakes, S.; Wu, D.; Kugler, S.Z., Jr.; Kashem, M.A.; Kaplita, P.; Snow, R.J. Identification of pharmacological inhibitors of the MEK5/ERK5 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Deng, X.; Lu, B.; Cameron, M.; Fearns, C.; Patricelli, M.P.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Gray, N.S.; Lee, J.D. Pharmacological inhibition of BMK1 suppresses tumor growth through promyelocytic leukemia protein. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces monocytic differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells by regulating C/EBPbeta expression through MEF2C. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumovskaya, E.; Sun, J.; Ronnstrand, L. Inhibition of MEK5 by BIX02188 induces apoptosis in cells expressing the oncogenic mutant FLT3-ITD. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 412, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, E.; Wiedlocha, A.; Radzikowski, C. Evidence that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p70S6K protein are involved in differentiation of HL60 cells induced by calcitriol. Anticancer Res. 1998, 18, 3507–3514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hmama, Z.; Nandan, D.; Sly, L.; Knutson, K.L.; Herrera-Velit, P.; Reiner, N.E. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced myeloid cell differentiation is regulated by a vitamin D receptor-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling complex. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, E.; Kutner, A. Side-chain modified vitamin D analogs require activation of both PI3-K and Erk1,2 signal transduction pathways to induce differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2002, 49, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hughes, P.J.; Lee, J.S.; Reiner, N.E.; Brown, G. The vitamin D receptor-mediated activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3Kalpha) plays a role in the 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-stimulated increase in steroid sulphatase activity in myeloid leukaemic cell lines. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 103, 1551–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baurska, H.; Kielbinski, M.; Biecek, P.; Haus, O.; Jazwiec, B.; Kutner, A.; Marcinkowska, E. Monocytic differentiation induced by side-chain modified analogs of vitamin D in ex vivo cells from patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2014, 38, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baurska, H.; Klopot, A.; Kielbinski, M.; Chrobak, A.; Wijas, E.; Kutner, A.; Marcinkowska, E. Structure-function analysis of vitamin D2 analogs as potential inducers of leukemia differentiation and inhibitors of prostate cancer proliferation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 126, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.D. Transcriptional control of granulocyte and monocyte development. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6816–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.H.; Langmann, S.; Schwarzfischer, L.; El Chartouni, C.; Lichtinger, M.; Klug, M.; Krause, S.W.; Rehli, M. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta regulates constitutive gene expression during late stages of monocyte to macrophage differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 21924–21933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Studzinski, G.P. Retinoblastoma protein and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta are required for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gocek, E.; Liu, C.G.; Studzinski, G.P. MicroRNAs181 regulate the expression of p27Kip1 in human myeloid leukemia cells induced to differentiate by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, R.; Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Gebauer, F. miR-181a regulates cap-dependent translation of p27(kip1) mRNA in myeloid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2841–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggal, J.; Harrison, J.S.; Studzinski, G.P.; Wang, X. Involvement of microRNA181a in differentiation and cell cycle arrest induced by a plant-derived antioxidant carnosic acid and vitamin D analog Doxercalciferol in human leukemia cells. Microrna 2012, 1, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, D.; Lv, X.B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Meng, W.; Yu, F.; Hu, H. Downregulation of miR-302c and miR-520c by 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment enhances the susceptibility of tumour cells to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iosue, I.; Quaranta, R.; Masciarelli, S.; Fontemaggi, G.; Batassa, E.M.; Bertolami, C.; Ottone, T.; Divona, M.; Salvatori, B.; Padula, F.; et al. Argonaute 2 sustains the gene expression program driving human monocytic differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocek, E.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.G.; Studzinski, G.P. MicroRNA-32 upregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human myeloid leukemia cells leads to Bim targeting and inhibition of AraC-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2012, 71, 6230–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatori, B.; Iosue, I.; Djodji Damas, N.; Mangiavacchi, A.; Chiaretti, S.; Messina, M.; Padula, F.; Guarini, A.; Bozzoni, I.; Fazi, F.; et al. Critical Role of c-Myc in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Involving Direct Regulation of miR-26a and Histone Methyltransferase EZH2. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatori, B.; Iosue, I.; Mangiavacchi, A.; Loddo, G.; Padula, F.; Chiaretti, S.; Peragine, N.; Bozzoni, I.; Fazi, F.; Fatica, A. The microRNA-26a target E2F7 sustains cell proliferation and inhibits monocytic differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesakhov, S.; Khanin, M.; Studzinski, G.P.; Danilenko, M. Distinct combinatorial effects of the plant polyphenols curcumin, carnosic acid, and silibinin on proliferation and apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pesakhov, S.; Weng, A.; Kafka, M.; Gocek, E.; Nguyen, M.; Harrison, J.S.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. ERK 5/MAPK pathway has a major role in 1alpha,25-(OH) vitamin D-induced terminal differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 144, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabtay, A.; Sharabani, H.; Barvish, Z.; Kafka, M.; Amichay, D.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y.; Uskokovic, M.R.; Studzinski, G.P.; Danilenko, M. Synergistic antileukemic activity of carnosic acid-rich rosemary extract and the 19-nor Gemini vitamin D analogue in a mouse model of systemic acute myeloid leukemia. Oncology 2008, 75, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. Enhancement by other compounds of the anti-cancer activity of vitamin D3 and its analogs. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 298, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Harrison, J.S.; Uskokovic, M.; Danilenko, M.; Studzinski, G.P. Silibinin can induce differentiation as well as enhance vitamin D3-induced differentiation of human AML cells ex vivo and regulates the levels of differentiation-related transcription factors. Hematol. Oncol. 2010, 28, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Danilenko, M.; Vassilev, L.; Studzinski, G.P. Tumor suppressor p53 status does not determine the differentiation-associated G1 cell cycle arrest induced in leukemia cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and antioxidants. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ikezoe, T.; Nishioka, C.; Ni, L.; Koeffler, H.P.; Yokoyama, A. Inhibition of mTORC1 by RAD001 (everolimus) potentiates the effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to induce growth arrest and differentiation of AML cells in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 2010, 38, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainey, E.; Wolfromm, A.; Sukkurwala, A.Q.; Micol, J.B.; Fenaux, P.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. EGFR inhibitors exacerbate differentiation and cell cycle arrest induced by retinoic acid and vitamin D3 in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2978–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilenko, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y.; Studzinski, G.P. Carnosic acid potentiates the antioxidant and prodifferentiation effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in leukemia cells but does not promote elevation of basal levels of intracellular calcium. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Callens, C.; Coulon, S.; Naudin, J.; Radford-Weiss, I.; Boissel, N.; Raffoux, E.; Wang, P.H.; Agarwal, S.; Tamouza, H.; Paubelle, E.; et al. Targeting iron homeostasis induces cellular differentiation and synergizes with differentiating agents in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen-Deutsch, X.; Kutner, A.; Harrison, J.S.; Studzinski, G.P. The pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh has anti-leukemia effects and can interact with vitamin D analogs to increase HPK1 signaling in AML cells. Leuk. Res. 2012, 36, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, F.; Zhang, J.; Harrison, J.S.; Wang, X.; Studzinski, G.P. Induction of differentiation of human leukemia cells by combinations of COX inhibitors and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 involves Raf1 but not Erk 1/2 signaling. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paubelle, E.; Zylbersztejn, F.; Alkhaeir, S.; Suarez, F.; Callens, C.; Dussiot, M.; Isnard, F.; Rubio, M.T.; Damaj, G.; Gorin, N.C.; et al. Deferasirox and vitamin D improves overall survival in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia after demethylating agents failure. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinicaltrials.gov. Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home (accessed on 12 October 2014).

- Cancer.gov. Available online: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials (accessed on 12 October 2014).

- Leukemia-net.org. Available online: http://www.leukemia-net.org/content/leukemias/aml/aml_trials/database/index_eng (accessed on 12 October 2014).

- Ferrero, D.; Crisa, E.; Marmont, F.; Audisio, E.; Frairia, C.; Giai, V.; Gatti, T.; Festuccia, M.; Bruno, B.; Riera, L.; et al. Survival improvement of poor-prognosis AML/MDS patients by maintenance treatment with low-dose chemotherapy and differentiating agents. Ann. Hematol. 2014, 93, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autier, P.; Gandini, S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannucci, E. Can vitamin D reduce total mortality? Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1709–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Muindi, J.R.; Tan, W.; Hu, Q.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Wilding, G.E.; Ford, L.A.; Sait, S.N.; Block, A.W.; et al. Low 25(OH) vitamin D3 levels are associated with adverse outcome in newly diagnosed, intensively treated adult acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2014, 120, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnath, N.; Daignault-Newton, S.; Dy, G.K.; Muindi, J.R.; Adjei, A.; Elingrod, V.L.; Kalemkerian, G.P.; Cease, K.B.; Stella, P.J.; Brenner, D.E.; et al. A phase I/II pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenomic study of calcitriol in combination with cisplatin and docetaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Ma, Z.; Li, W.; Ma, Q.; Guo, J.; Hu, A.; Li, R.; Wang, F.; Han, S. The mechanism of calcitriol in cancer prevention and treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4121–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro, S.; Goldsmith, D.; Larsson, T.E.; Massy, Z.A.; Cozzolino, M. Vitamin D metabolites and/or analogs: Which D for which patient? Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gocek, E.; Studzinski, G.P. The Potential of Vitamin D-Regulated Intracellular Signaling Pathways as Targets for Myeloid Leukemia Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 504-534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4040504

Gocek E, Studzinski GP. The Potential of Vitamin D-Regulated Intracellular Signaling Pathways as Targets for Myeloid Leukemia Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2015; 4(4):504-534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4040504

Chicago/Turabian StyleGocek, Elzbieta, and George P. Studzinski. 2015. "The Potential of Vitamin D-Regulated Intracellular Signaling Pathways as Targets for Myeloid Leukemia Therapy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 4, no. 4: 504-534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4040504